How to overcome child labour

Five ways we can help to eliminate child labour

“There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.” – Nelson Mandela

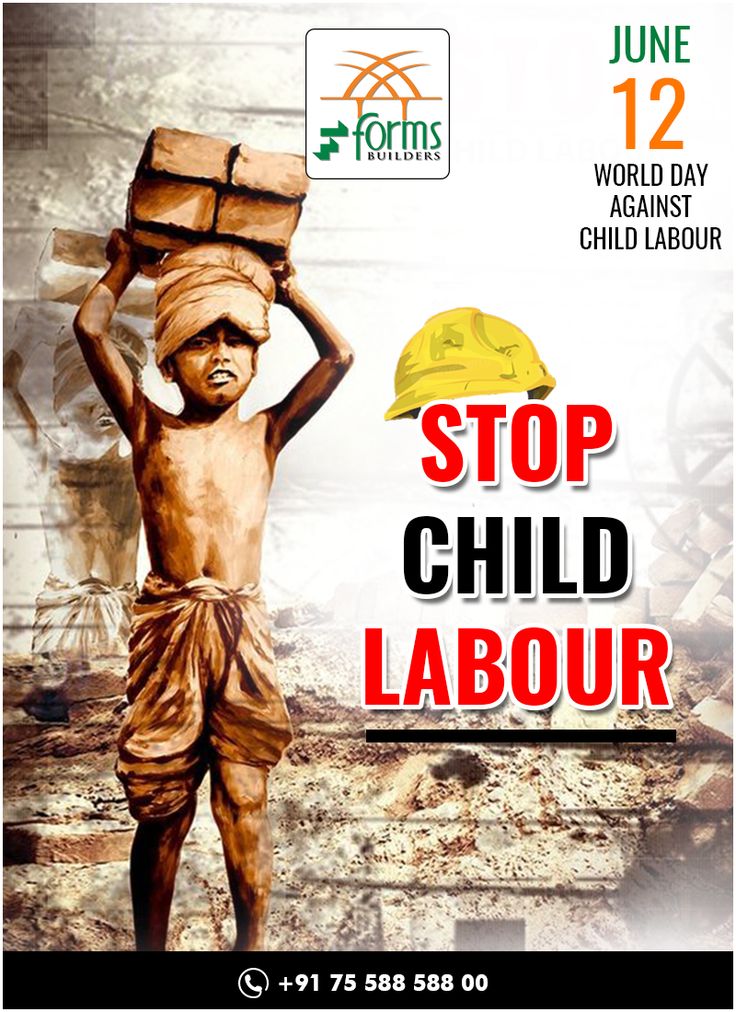

The World Day Against Child Labour, which is held every year on June 12, is intended to foster the worldwide movement against child labour in all of its forms. This year’s theme looks to shine a spotlight on the global need to improve the safety and health of young workers and end child labour.

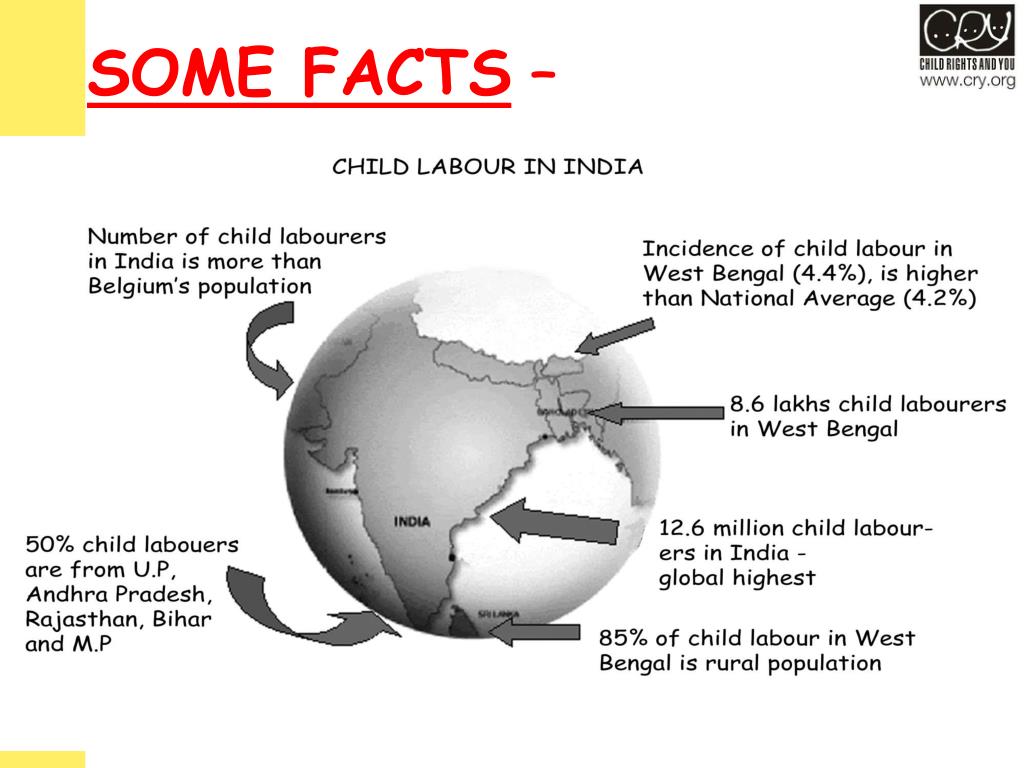

Facts about Child Labour:

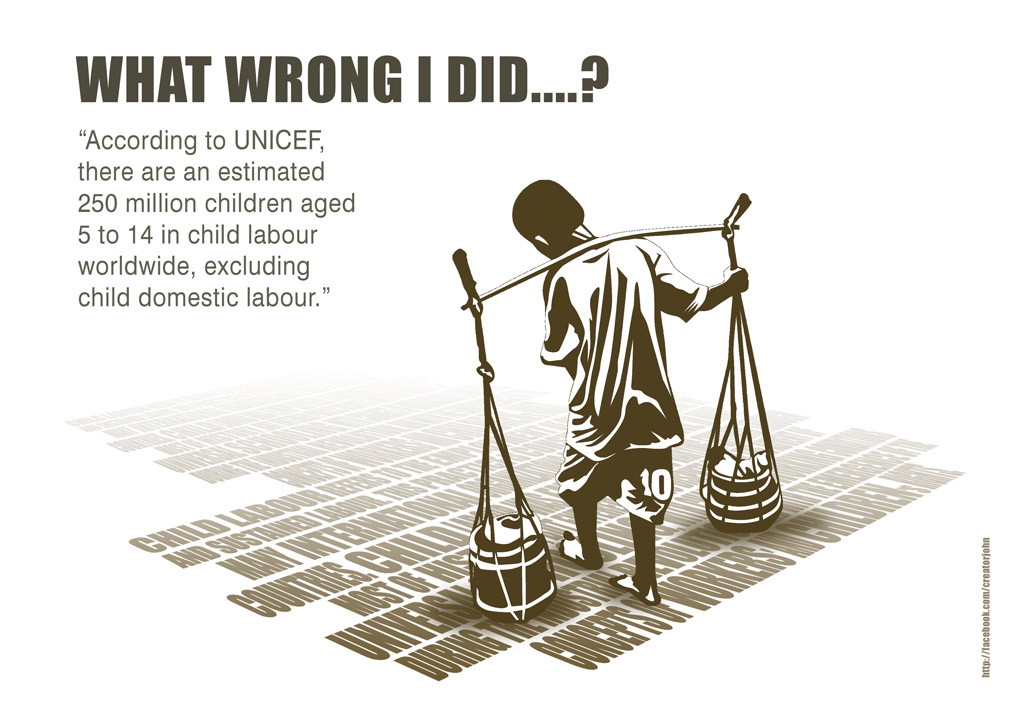

- Worldwide 218 million children between 5 and 17 years are in employment

- In the world’s poorest countries, around one in four children are engaged in work that is potentially harmful to their health

- Among 152 million children in child labour, 88 million are boys and 64 million are girls

- 1 in 5 children in Africa is working in child labour

Below you will find 5 ways we can help eradicate child labour in all its forms:

1.Photo credit: Unsplash

Children do not work because they want to, and parents would ideally much rather see their children receive an education. Child labour is socially accepted when people see no other option but to send their children to work. Governments must abide by internationally accepted agreements, companies must employ adults instead of children and – importantly – consumers must not buy goods produced by child labour.

2. Increased access to educationPhoto credit: Unsplash

Removing children from child labour does not mean that they will automatically attend school. Schooling can be expensive, or of very poor quality, and so some parents think sending their children to work is the obvious alternative. Both large and smaller businesses can make their contribution by raising awareness about the importance of education in their workplaces, communities, industries or sectors.

3. Provide support for children

Provide support for childrenPhoto credit: Pexels

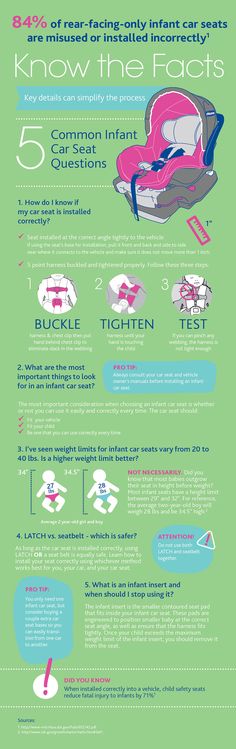

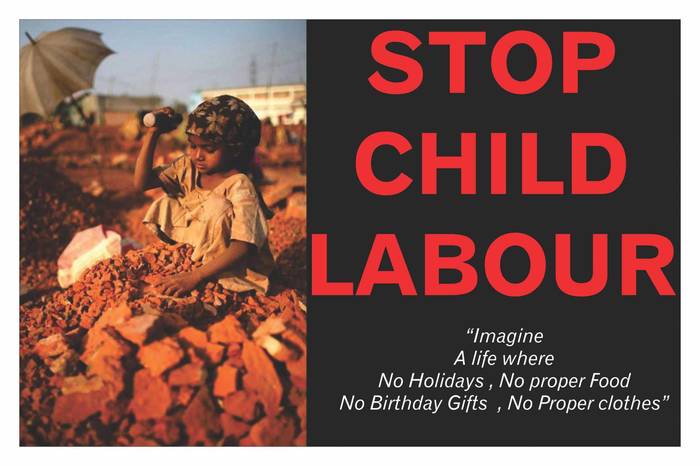

Children are also at greater health and safety risk in the workplace for a number of reasons:

- Lack work experience – children are less able to make informed judgments.

- Want to perform well – children are willing to go the “extra mile” without realising the risks.

- Learn unsafe health and safety behaviour from adults.

- Might not be carefully trained and supervised.

Photo credit: Unsplash

As many as 7.8 million Indian children are forced to earn a livelihood even if they also attend school. Many of these children drift away from the path of education completely and get end up in child labour. This means a country has a lack of formally educated adults who can contribute to the process of nation-building and to the country’s economic growth.

5. Engage with the Sustainable Development GoalsPhoto credit: Unsplash

We know that the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015, will only succeed if we work towards the goals together. The sub-Saharan African region is among those affected by situations of extreme poverty, state fragility and crisis, and by natural disasters and population displacements associated with global climate change, which in turn are known to heighten the risk of child labour.

The sub-Saharan African region is among those affected by situations of extreme poverty, state fragility and crisis, and by natural disasters and population displacements associated with global climate change, which in turn are known to heighten the risk of child labour.

6 Steps to Zeroing Out Child Labour Globally

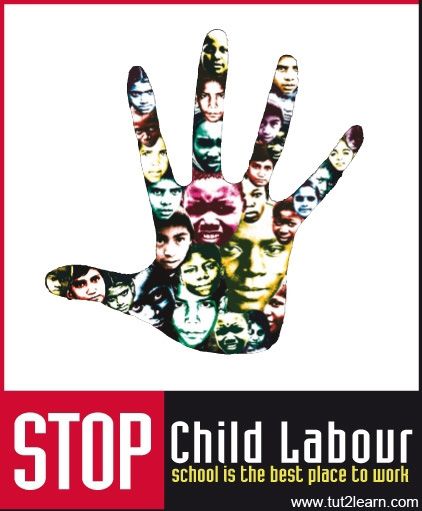

Child labour is a violation of every child’s right to a childhood.

When children can not achieve their full potential, it tears at a countries’ social fabric and directly diminishes its economic growth.

And even as these dire consequences are known, child labour has increased globally to 160 million. This means that every one in 10 children age five and over in the world today are trapped in child labour. 70% of all child labour takes place in the agriculture sector. Right now there are six steps that can be taken to end child labor and to ensure a brighter, more fulfilling future for all countries.

1. Making Decent Work a Reality for Adults and Youth

Governments should embrace internationally recognised fundamental rights at work including ending forced labour, discrimination at work, respecting workers’ right to freely choose representation and ensuring safe and healthy working conditions. These core rights are increasingly being used in free trade agreements, due diligence directives and codes of conduct to spur change.

These core rights are increasingly being used in free trade agreements, due diligence directives and codes of conduct to spur change.

Decent work requires an adequate minimum wage based on dialogue and collective bargaining between workers’ organisations and employers. It also requires formalizing the informal economy and extending the coverage of labour law for protection to those who are the most vulnerable.

Governments also need to create an enabling environment for sustainable enterprises to prosper, invest and create decent work opportunities for all women and men who are above the minimum age for work.

2. Ending Child Labour in Agriculture

Since child labour exists disproportionately in the agricultural sector, an investment strategy for rural areas focused on increasing access to finance and credit is critical. Facilitating smallholder farmers’ access to financial markets enables them to hedge against risks they face so they can invest in more profitable entrepreneurial activities.

The building of coalitions between Ministries of Agriculture, Labour Inspectors with employers’ organizations and workers’ organizations is essential for ongoing dialogue and collaboration in developing national policies.

This should include improving labour conditions, adopting safe agricultural practices to reduce work-related hazards and exposure to harmful substances as well as transitioning to more sustainable technologies.

Countries should also strengthen agricultural labour markets data collection and information systems and create decent work opportunities for youth, women and men through innovative vocational training in agri-food production and processing services.

3. Enhancing Data-Driven Policies and Programmatic Responses

The strengthening of regular data collection and management systems – with disaggregated data by sex and age – on child labour in agriculture, mining, domestic work, the service sector, and manufacturing sectors is critical to better policies and programmes.

Developing gender-sensitive responses such as universal access to birth registration, adequate nutrition, accessible and affordable quality childcare, child protection and quality education services should be a priority.

This data and its analysis can help governments increase the capacity of law enforcement bodies, labour inspectorates, agricultural extension services, child protection and education services to investigate, prevent and mediate child labour and forced labour situations.

A special focus is also needed to end child labour in supply chains by promoting and supporting transparency, due diligence and remediation in private and public supply chains and procurement policies.

4. Realizing Children’s Right to Education

Eliminating barriers to quality, compulsory education for girls and boys, such as distance, cost of education, improving learning outcomes, safety and gender-based violence and exploitation can boost school enrolment.

The provision of relevant training, skills development and vocational education for girls and boys above the minimum age for employment, including quality apprenticeships, skills matching and school-to-work transitions help better align applicants with labour market needs and opportunities.

5. Achieving Universal Access to Social Protection

Governments need to progressively extend access to comprehensive, adequate, sustainable, and inclusive social protection measures to their populations throughout their lives to prevent poverty, reduce inequality and combat social exclusion.

These measures include access to health care, family allowances, unemployment benefits, old age and disability pensions, and maternity benefits, among others, working in tandem with services, including child, health and long-term care services.

These should target and increase access of communities depending on agriculture for their livelihoods to social and agricultural insurances as well as expanding child labour monitoring systems, linked to the provision of social protection services.

6. Increasing Financing and International Cooperation

The range of benefits and services listed above need to be paid for by governments and requires better domestic resource mobilization to develop and adequately fund national action plans, improve statistics and other data collection on child labour, and integrating child labour concerns into relevant national development policies and plans.

Coordination will be key to the success of this approach requiring policy coherence, particularly between social, trade, agricultural, financial, labour, economic, education and training and environmental policies, in pursuit of a human-centred approach to a future of work free of child labour and forced labour.

It will also require strengthening cross-sectoral cooperation to mainstream child labour elimination into other international priorities, notably climate change, environmental protection, hunger eradication, poverty reduction, addressing inequalities, decent jobs, clean energy, digitalisation, water and sanitation, peacekeeping and peacebuilding, migration, youth empowerment, and gender equality.

And finally, enhancing international cooperation to eliminate child labour and forced labour among indigenous and tribal peoples, minority groups, migrant populations and other vulnerable groups, and to mobilize national and regional responses to eliminate the commercial sexual exploitation of children.

The elimination of child labour can not be achieved by inaction nor by legislating it away. It is a complex and sadly, deeply rooted development challenge. Child labour is largely driven by poverty and a lack of decent work opportunities for parents and communities mired in abject poverty.

However, the road to the elimination of child labour also leads to the realization of decent work and social justice which will go very far in ensuring that other deeply embedded social and economic development challenges are also being tackled. These dividends will certainly be enjoyed by the wider community of nations and future ready next generation of leaders.

Read more about the global effort to end child labour in this joint report by the ILO and UNICEFOpens new window

About the Author

Kevin Cassidy

Director and Representative to Bretton Woods and Multilateral Organizations ILO Office for the United States and Canada

Kevin Cassidy, with nearly 4 decades of international development experience, is currently the Director and Representative to the Bretton Woods and Multilateral Organizations for the International Labour Organization (ILO) Office for the United States.

How to prevent the exploitation of children in conflict? |

Archive audio

Download

Millions of children around the world are forced to work - often in very difficult and unsafe conditions. On June 12 - World Day against Child Labor - remind the UN. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has released new guidance on preventing the exploitation of children in times of crisis. Learn more about what amounts to exploitation and how to help children remain children, even in situations of armed conflict, with FAO Representative Jacqueline Demeranville.

*****

“Exploitation of child labor is work that poses a threat to the health, safety, morale of the child, as well as work that does not allow the child to receive an education. It is also the involvement of children under a certain age in the work.

It is also the involvement of children under a certain age in the work.

In short, from the point of view of international law and the legislation of most countries, a teenager who sprays pesticides, or a child who cannot go to school because he has to work, are victims of exploitation. At the same time, says FAO's Jacqueline Demeranville, in certain cases, the involvement of children in labor is acceptable.

“Working in a safe environment, work that does not interfere with the child's education and is appropriate for the child's age may be considered legitimate. In rural areas, working "on the ground" can be beneficial for children. It helps them acquire the skills they will need in the future.”

However, working conditions in the fields rarely meet these acceptance criteria. Sometimes children are forced to do very hard work, replacing adults. Most often, children living in a conflict zone or caught in the epicenter of a natural disaster find themselves in such a situation.

“Natural disasters and armed conflicts destroy the habitual life of people, destroy their property, for example, livestock. In such conditions, children stop going to school, because they have to help their families survive, earn money, get food. Some children lose loved ones during war or natural disasters. They have to work so as not to die of hunger.”

Children who were exploited before the outbreak of conflict face new threats to life and health in the context of hostilities. They may come under fire in open areas, or run into mines and unexploded ordnance while working in the field.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reminds that child labor is just one of the many problems people face in armed conflict. FAO's new leadership should help affected communities cope with the impact of the crisis and prevent the emergence of a "lost generation".

“Social institutions that protect children's rights and educational institutions play a very important role in times of conflict. But it is also important that various agricultural organizations and programs do their best to protect children from exploitation. They should help families to quickly restore the economy and return to normal life. Thanks to programs to support farmers and develop agriculture, children will be able not to overwork and go to school.”

But it is also important that various agricultural organizations and programs do their best to protect children from exploitation. They should help families to quickly restore the economy and return to normal life. Thanks to programs to support farmers and develop agriculture, children will be able not to overwork and go to school.”

Photo Credit

ILO Photo

Children

Interviews

Human Rights

Reporting

Child slavery: every 10th child in the world is exploited: Society articles ➕1, 07/23/2021

There are many more victims of child labor on the planet than the inhabitants of Russia. Half of them are employed in its most dangerous forms. The number of child laborers has been steadily increasing over the past five years, and amid the COVID-19 crisisthe situation could get worse. Plus-one.ru selected the highlights from the latest International Labor Organization (ILO) report on successes and failures in the global fight against child labor.

At the beginning of 2020, there were 160 million victims of exploitation on the planet (every 10th child between the ages of five and 17). Nearly half of them—79 million children—were involved in the most dangerous forms of child labour, doing work that directly endangers health, safety, or moral development.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the world has made significant progress in solving this problem. In 2000, there were one and a half times more victims of child labor than today (and twice as many victims of its most dangerous forms).

The latest ILO data shows that progress stopped five years ago and has been steadily reversing since then. From 2016 to 2020, for the first time in the history of statistical monitoring, the number of victims of child labor did not decrease, but grew: by 8.4 million in four years, and almost 80% (6.5 million) of these children were involved in the most dangerous forms of labor.

The precise definition of child labor has been revised several times. At the moment, the wording adopted by the ILO in 2008 has been adopted for statistical estimates. According to it, the victims of child labor include:

children aged 5-11 involved in any form of employment;

children aged 12-14 working 14 or more hours a week;

children aged 5-14 engaged in unpaid domestic work 21 or more hours per week;

children aged 5-17 working 43 or more hours per week;

children aged 5-17 who work in certain hazardous industries or in certain hazardous jobs (their lists include dozens of items, from mining or construction jobs to certain forms of unpaid domestic work).

The last three items describe victims of the most dangerous forms of child labor. As you can see, the ILO is not at all opposed to children working. Let's say a 12-year-old child can do housework for an hour a day, and a 15-year-old can work for hire for eight hours, five days a week, in a non-hazardous industry. In these cases, they will not be included in the statistics of victims of child labor.

Let's say a 12-year-old child can do housework for an hour a day, and a 15-year-old can work for hire for eight hours, five days a week, in a non-hazardous industry. In these cases, they will not be included in the statistics of victims of child labor.

Freedom, equality, slavery

What is the scale of human exploitation in a world that fights for human rights

The world has been making efforts to eliminate child labor for almost 50 years. In 1973, the ILO adopted the Convention on the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment, according to which, in the 173 states that have ratified it, official employment is possible only from 16 or 18 years. Numerous similar documents have appeared before (since 1919, the year the ILO was founded), but all of them covered only certain industries.

In 1999, the Convention on the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor was issued. These, according to the document, include slavery, forced labor, prostitution, military service, production of pornography, distribution of drugs, work at high or low temperatures and other work that endangers the health, safety or morals of children. In 2020, this convention became the first document in history to be ratified by all 187 ILO member countries.

These, according to the document, include slavery, forced labor, prostitution, military service, production of pornography, distribution of drugs, work at high or low temperatures and other work that endangers the health, safety or morals of children. In 2020, this convention became the first document in history to be ratified by all 187 ILO member countries.

In September 2015, the UN member states adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 8 included the target “by 2025, end child labor in all its forms”. Even then, it seemed, to put it mildly, optimistic: in 10 years it was supposed to put somewhere more than 150 million victims of child labor, while over the previous 15 years their number was reduced by 100 million. Against the backdrop of regression in recent years, target 8.7 looks unfeasible.

Its obvious cause is poverty. In low-income countries, more than a quarter of children aged five to 17 are involved in the labor force, while in middle-income countries it is less than 10%, and in high-income countries it is less than 1%. However, poverty comes in many forms and is ubiquitous in varying degrees. Nearly 60% of all victims of child labor (93.4 million children) are in middle-income countries.

However, poverty comes in many forms and is ubiquitous in varying degrees. Nearly 60% of all victims of child labor (93.4 million children) are in middle-income countries.

More than half of all victims of child labor (86.6 million children) live in sub-Saharan Africa. In this region, every fourth child aged 5-17 is involved in child labor.

However, this was not always the case. At the beginning of the 21st century, most of the exploited boys and girls were in the countries of the Asia-Pacific region. From 2008 to 2020, there has been continuous progress - the number of victims of child labor has decreased by 65 million people, almost 2.5 times. Another region in which the situation continues to improve, albeit at a less impressive pace, is the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the opposite is true. The number of those involved in child labor in this region stopped declining in 2012 and has been continuously growing since then. Moreover, the pace of this growth completely overlaps the progress in other regions combined.

Moreover, the pace of this growth completely overlaps the progress in other regions combined.

Boys are involved in child labor more often than girls: 97 million male children (11.2% of all boys on the planet) versus 63 million female children (7.8% of all girls). Among children aged 5-14, the gender gap is half as large, as girls are much more likely to have to do more than 21 hours of housework per week.

More than 3 million girls undergo genital mutilation every year

11 facts about practices that injure women and children

More than half of all victims (nearly 90 million children) are in the 15-17 age group. Children aged 5-11 make up one-fifth (35 million) of those involved in child labor, as do children aged 12-14. From 2000 to 2016, the number of child labor victims declined among all three age groups. But in the last five years, in the 12-14 and 15-17 year old groups, this progress continued, and in the 5-11 year old group, it began to reverse. By 2020, the number of children of this age involved in child labor was 16.8 million more than in 2016.

By 2020, the number of children of this age involved in child labor was 16.8 million more than in 2016.

Most child labor victims (112 million) are employed in agriculture. About a fifth (32 million) is in the service sector (including unpaid domestic work). 16.5 million children (one tenth) work in industrial enterprises. Child labor is three times more common in rural areas (122.7 million victims) than in cities (37.3 million victims).

72% of all victims of child labor and 83% of victims aged 5-11 are exploited by relatives. Most of these children work on family farms or micro-enterprises. Contrary to the popular perception of the family as a safe working environment, one in four children aged 5-11 and almost half of children aged 12-14 in their own families are engaged in work that is harmful to their health, safety or moral development.

Child labor is a major barrier to education. 35% of all victims do not go to school, among children aged 5-11 this figure is 27. 7%, among children aged 15-17 - 53.2%. Lack of basic education severely limits the prospects for a decent job in youth and adulthood. Those children who manage to combine work with school suffer from the need to find compromises between them, most often not in favor of studying. At the same time, they are practically deprived of the right to leisure.

7%, among children aged 15-17 - 53.2%. Lack of basic education severely limits the prospects for a decent job in youth and adulthood. Those children who manage to combine work with school suffer from the need to find compromises between them, most often not in favor of studying. At the same time, they are practically deprived of the right to leisure.

In 2019There were 582 million children worldwide living in low-income families worldwide. In 2020 alone, the pandemic crisis has increased the number of such children to 724 million. All of them are now at risk, as, having lost their sources of income, many families turn to child labor as a way to survive.

The closure of educational institutions during the lockdown increases the risks: freed from the need to attend school, children from low-income families are more likely to start working. And not everyone is able to return to school.

Principles and beggars

What stands in the way of ending poverty

Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to further undermine the already stalled global progress in the fight against child labour. An ILO analysis shows that, unless urgent additional social support measures are taken to support low-income families, by the end of 2022 the number of victims of child labor will increase by almost 9 million. More than half (4.9 million) of them will be among children 5-11 years old.

An ILO analysis shows that, unless urgent additional social support measures are taken to support low-income families, by the end of 2022 the number of victims of child labor will increase by almost 9 million. More than half (4.9 million) of them will be among children 5-11 years old.

In the worst case scenario, if the coverage of social assistance not only does not expand, but also decreases - for example, as a result of austerity measures during the crisis, then 46 million more children will be involved in child labor in 2022 than in 2020 . This will throw the world back 20 years, to the indicators of the early 2000s.

On the other hand, with the proper expansion of social support measures, by the end of 2022, it is possible to achieve a reduction in the number of victims of child labor by 15.1 million, which will fully offset the negative effect of the pandemic.

Modeling these scenarios, the ILO experts did not operate with money, but with indicators of social support coverage.