How to legally hyphenate a child's last name

How to Legally Hyphenate Your Name

Reviewed by: Karen Lac, J.D.

January 26, 2019

By: Liz Cobbs

••• Thinkstock/Comstock/Getty Images

Hyphenating a name generally occurs when a woman gets married and keeps her maiden name while taking on her husband's last name. Some women show their marriage license as proof of their newly hyphenated name. However, some states require women to legally change their name through a court process. A legal name change is also required for people who want to hyphenate their names for reasons other than marriage.

Name Change Assistance

File a name change petition in probate court or circuit court in the county in which you live. Procedures for legal name changes vary from state to state. In some states, name changes are handled by the circuit court's clerk's office. In other states, the county probate court handles them. Call your local county courthouse to find out which court handles names changes in your area. Also ask about the procedure and cost for filing the petition. Check to see if the court in your area has name change petitions and instructions on the Internet that you can download or that you can pick up in person.

Step 1: File the Name Change Petition

File the request for a name change hearing. Petitions for hearings are filed in the court clerk's office. In some cases, the clerk's office will automatically schedule a court hearing after the name change petition has been filed. Prior to holding a court hearing, some states require applicants to have their fingerprints taken so that police can conduct a criminal background check.

Read More: How to Publish a Petition for a Name Change

Step 2: Provide Public Notice of Your Name Change Request

Publish the name change hearing form in a local newspaper. States require applicants to place a legal notice of the hearing in a newspaper of general circulation in their county. After the notice is published, newspapers will give applicants a proof of publication statement to take to court.

Step 3: Attend the Court Hearing

Attend the court hearing. Take a certified birth certificate and the proof of publication statement to show the judge. The judge may answer questions to the applicant about reasons for wanting a name change. If the judge is satisfied with the applicant's information and answers, the judge will sign an order granting the name change.

Step 4: Get Certified Copies of Your Name Change Order

Once your have a court order, file the name change order with the clerk's office. In some states, this is done automatically. Then get at least one certified copy of the name change order for your own record. It's wise to actually order several certified copies of your name change order so that you immediately have one on hand for whomever requires such proof.

Step 5: Send Proof of Your Name Change

Once you have a name change order, you can send and show copies of it as proof of your name change. Generally, in order to change your name on government-issued identification documents such as your driver's license, passport and social security card, you will need to send a certified copy of the name change order to the department that handles name changes.

Besides getting a new driver's license, passport and social security card, you may want to notify employers, banks, credit card companies, utility companies, and other government agencies that you deal with of your legal name change.

Many states provide an informational packet and/or a website that lays out all of the documents that you'll need to file and the steps to follow to legally change your name. Check with your local courthouse to see what assistance is provided.

References

- Basic Steps to Handling a Name Change

- Name Change-Probate Court, Franklin County, Ohio

Writer Bio

Liz Cobbs has been a professional writer since 1985. She has worked as a staff reporter at "The Ann Arbor News" and "The Ypsilanti Press" newspapers, and as an assistant manager of editorial services at Eastern Michigan University. Cobbs earned a B.A. in music theory from Wayne State University and an M.A. in communication from Regent University.

Changing A Child’s Last Name Over The Objection Of One Of The Parents

Civil Rights Law § 63 authorizes a child’s name change if there is no reasonable objection to the proposed name, and the interests of the infant will be substantially promoted by the change. Under what circumstances will the Court allow a change over the objection of one of the parents?

The following case sheds light on what the court will consider upon an application for a name change.

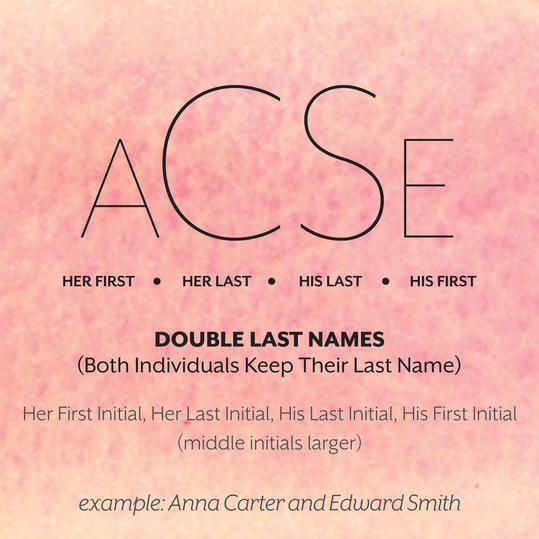

Michelle I. Esquenazi (the mother) and John Eberhardt (the father) are the parents of a daughter, Mariah (hereinafter the child). When the child wasborn, the parties had been in a committed relationship for a number of years and lived together along with the mother’s three children from a prior marriage. The parties had been planning on marrying at the time, but decided to postpone the wedding until after the child’s birth. The child was born, and she was given the father’s surname, as reflected by the child’s birth certificate and the acknowledgment of paternity. A wedding never took place. Approximately 1½ years after the child’s birth, the father moved out of the parties’ home. The mother maintained physical and legal custody of the child, with the father visiting her regularly.

A wedding never took place. Approximately 1½ years after the child’s birth, the father moved out of the parties’ home. The mother maintained physical and legal custody of the child, with the father visiting her regularly.

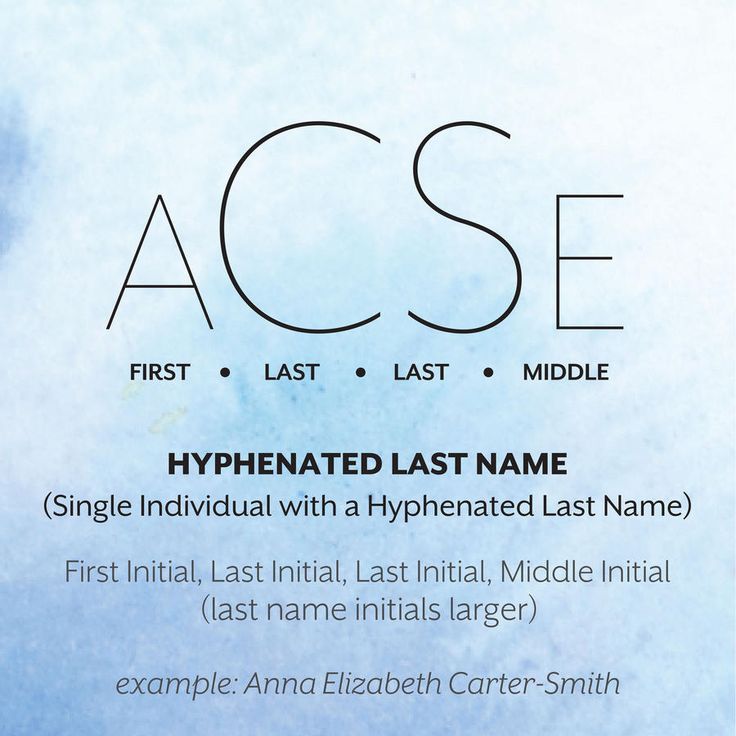

The mother petitioned the Supreme Court for permission to change the child’s surname by hyphenating the father’s surname with the mother’s surname.

At a hearing on the petition, the mother testified that during her pregnancy, she and the father “discussed” the child having both parties’ last names. Although only the father’s surname was used on the child’s birth certificate, an announcement of the child’s birth used both parties’ surnames.

At 2½ years of age, the mother testified that the child was baptized into the Lutheran Church. Leading up to the baptism, the parties had discussed using both parties’ surnames, as the mother claimed that she wanted the child to identify with both parents and to share the surnames of her maternal and paternal half-sibling. The parties attended the baptism, and the pastor announced the child to the congregationas Esquenazi-Eberhardt. The baptismal certificate, which the father saw, reflected the child’s surname as a combination of the parties’ surnames. The mother claimed that the father did not object to the child’s surname.

The parties attended the baptism, and the pastor announced the child to the congregationas Esquenazi-Eberhardt. The baptismal certificate, which the father saw, reflected the child’s surname as a combination of the parties’ surnames. The mother claimed that the father did not object to the child’s surname.

The child was enrolled in preschool, registered as Esquenazi-Eberhardt, and again under the same hyphenated surname when she started kindergarten. The father attended various school functions, including the child’s graduation from preschool to kindergarten, and then kindergarten to the first grade, where the parties’ hyphenated name was used during the roll-call of graduates, in pamphlets announcing the graduates, and graduation certificates, all without objection from the father.

At around four years of age, the child began to write her hyphenated name. In school, on important tests or pieces of artwork, the child would write out both full surnames, while on informal assignments she abbreviated the hyphenated surname to “E. E.”

E.”

It was the child’s self-identification as Esquenazi-Eberhardt that the mother offered as a reason why the name change would promote the child’s best interests. The hyphenated name gave the child a connection with both parents, her paternal and maternal half-siblings, and her ethnic heritage, Cuban-American on the mother’s side, and Native-American on the father’s side.

The father testified that when the child was born, there was never really any conversation about the child’s last name. It was simply a given that she would have only his surname, as the parties were planning on marrying and he was the father.

The father denied ever seeing or hearing the child’s hyphenated surname used in the birth announcement, at the baptism, or at school events such as the child’s graduation from kindergarten and, if he attended, preschool. He claimed that he never acquiesced to the child using both surnames. On both the custody and support orders, the child had only the father’s surname. The father testified that the first time he saw the hyphenated surname used was when the mother filled out a passport application. The second time, the child came to the father’s home with a report card that contained the mother’ssurname, with the father’s surname penciled in next to it. The mother explained, when he questioned her, that the school had made a mistake, using the mother’s surname because one of her other children attended the same school. The mother told him that she would have it corrected.

The father testified that the first time he saw the hyphenated surname used was when the mother filled out a passport application. The second time, the child came to the father’s home with a report card that contained the mother’ssurname, with the father’s surname penciled in next to it. The mother explained, when he questioned her, that the school had made a mistake, using the mother’s surname because one of her other children attended the same school. The mother told him that she would have it corrected.

The father claimed that he had seen the child use the hyphenated surname in writings, but that was after he objected to her using it.

Asked why he objected to the proposed name change and why retaining the child’s current surname would promote her best interests, the father answered,

“Moralistic values, traditional values. Her name is and always was legally Mariah Ruby Eberhardt and I don’t see any reason or need for it to be changed. It was never agreed upon between the mother and myself, and I think the lesson that’s learned from being able to make anything, anything you want, any time you want to, is really a deviation of values and morals that should be instilled in a child. ”

”

The father believed that a hyphenated name announced to the world that the child came from a broken relationship. He asserted that the questions that would come from her hyphenated surname would be a source of embarrassment.

The lower court dismissed the mother’s proceeding finding that the father had reasonable objections to the name change. He was involved in the child’s life; he visited with her, provided her with emotional and financial support, and included her in his extended family. The Supreme Court indicated that in the absence of misconduct, abandonment, or lack of support, the application should not be granted.

Further, the Supreme Court concluded that the mother had failed to establish that the proposed name change was in the child’s best interests. The Supreme Court credited the father’s testimony that he never acquiesced in the use of the hyphenated name for the child. The use of the hyphenated name, the Supreme Court found, appeared to promote the interests of the mother, and not the child. Were the mother’s petition to be granted, it would reward her for her unilateral action in teaching the child to identify herself with a hyphenated name, and such would be contrary to the child’s best interests.

Were the mother’s petition to be granted, it would reward her for her unilateral action in teaching the child to identify herself with a hyphenated name, and such would be contrary to the child’s best interests.

Upon appeal the Appellate court reversed the Supreme Court and granted the mother’s application, stating that while the father raised objections to the proposed name change, they were not reasonable and that his concerns had no relation to the best interests of the child, nor did they bear on his relationship with the child. The father’s objections were directed toward the mother, for her having unilaterally taught the child to identify with both parents’ surnames.

The Appellate Court further stated that the lower court’s reliance on cases where the mother was seeking to change the child’s surname from the father’s last name to that of the mother was misplaced, as the mother in this case is not seeking to eliminate the father’s surname. Certainly a parent’s misconduct, abandonment, or lack of support is relevant in any proposed name, but where the mother is merely seeking to add her last name and not to eliminate the father’s name, the fact that the father supports the child does not preclude the proposed change.

To the extent the father’s objection was based on traditional values, meaning that it is Anglo-American custom to give a child the father’s name, the objection is not reasonable, because neither parent has a superior right to determine the surname of the child. Moreover, the objection must relate to the child’s best interests or bear on the parent’s relationship with the child, and the father failed to articulate, nor could he, how custom was relevant to either of those concerns.

Contrary to the father’s testimony at the hearing, the Appellate Court indicated that the use of the child’s hyphenated name does not announce to the world that she comes from a broken family, as some married couples choose to give their child a hyphenated surname. More importantly, the Court would not accord preference to paternal surnames in the context of determining the bests interest for the child.

In any case involving the best interests standard, the Court stated that whether a child’s best interests will be substantially promoted by a proposed name change requires a court to consider the totality of the circumstances.

Among the myriad of factors or circumstances that a court may consider in determining whether a proposed name change substantially promotes the child’s best interests, there are several that warrant special mention: (1) the extent to which a child identifies with and uses a particular surname; (2) the child’s expressed preference, if of sufficient age and maturity to articulate a basis for preferring a particular surname; (3) whether the child’s surname differs from the surname of the custodial parent; (4) the effect of the proposed name change on the child’s relationship with either parent; (5) whether the child’s surname is different from any of her siblings and the degree to which she associates and identifies with siblings on either side of her family; (6) whether the child is known by a particular surname in the community; (7) the misconduct, if any, of a parent, such as the failure to support or visit with the child; and (8) the difficulties, harassment, or embarrassment that the child may experience by bearing the current or proposed surname .

Considering these factors and the fact that the mother is seeking only to add her surname to the child’s current surname, the proposed name change to hyphenate the child’s surname to include both parents’ last names substantially promotes the child’s best interests. The child considers her last name to be Esquenazi-Eberhardt as evidenced by, among other things, the fact that she regularly writes the hyphenated name. The child has been using the hyphenated name for a number of years, and she is generally known in the community by her hyphenated name. Thus, to require the child to revert back to the surname given to her at birth may cause her difficulties, harassment, or embarrassment. The use of the hyphenated name will be a symbolic reminder of, and source of identification and association with, both her father and her mother, the mother having always been the child’s custodial parent. The hyphenated name will also be a reminder of the ethnic heritage of both parents, as well as her half-siblings on each side.

Accordingly, because there was no reasonable objection to the proposed name, and the interests of the child would be substantially promoted by the change, the mother’s petition is granted and Mariah was allowed to continue to use the hyphenated surname.

Rating: 5.0/5 (2 votes cast)

Changing A Child's Last Name Over The Objection Of One Of The Parents, 5.0 out of 5 based on 2 ratings

Follow

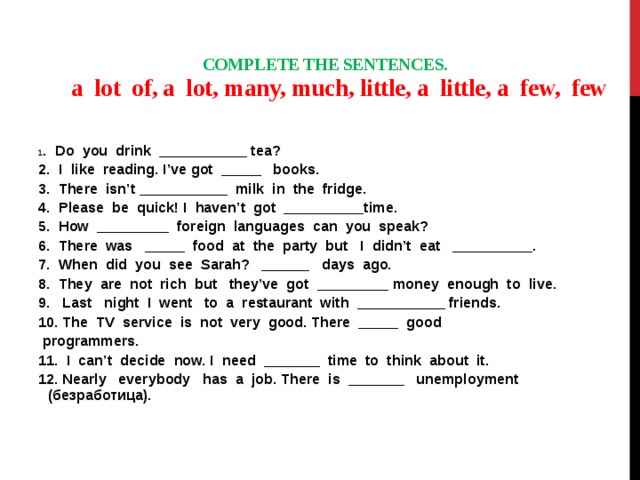

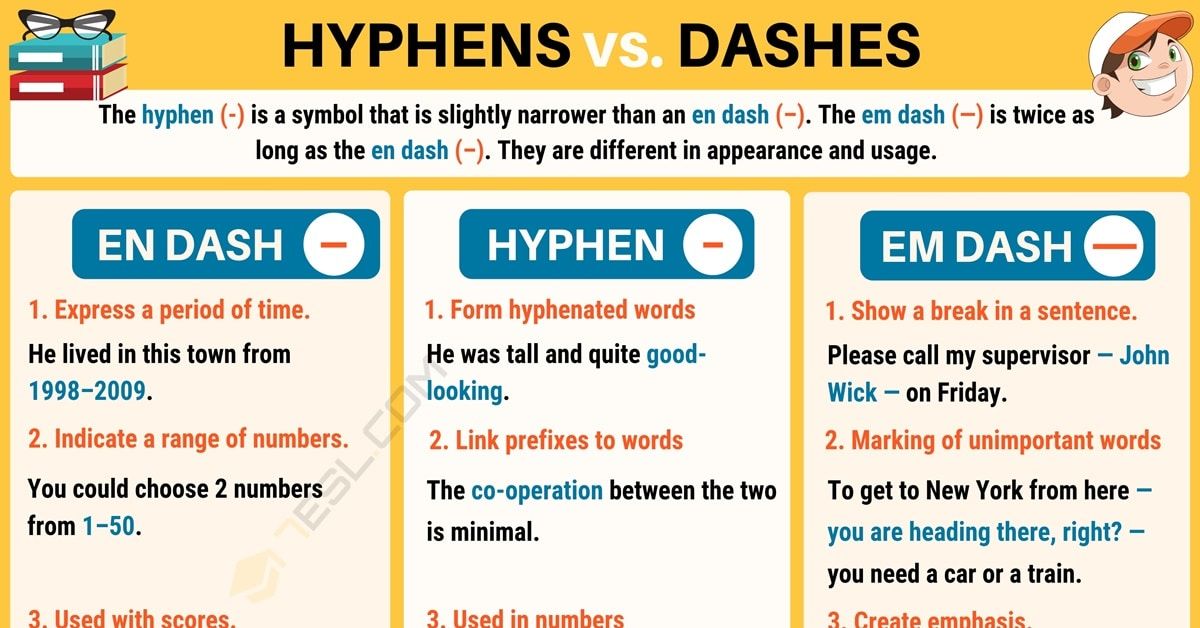

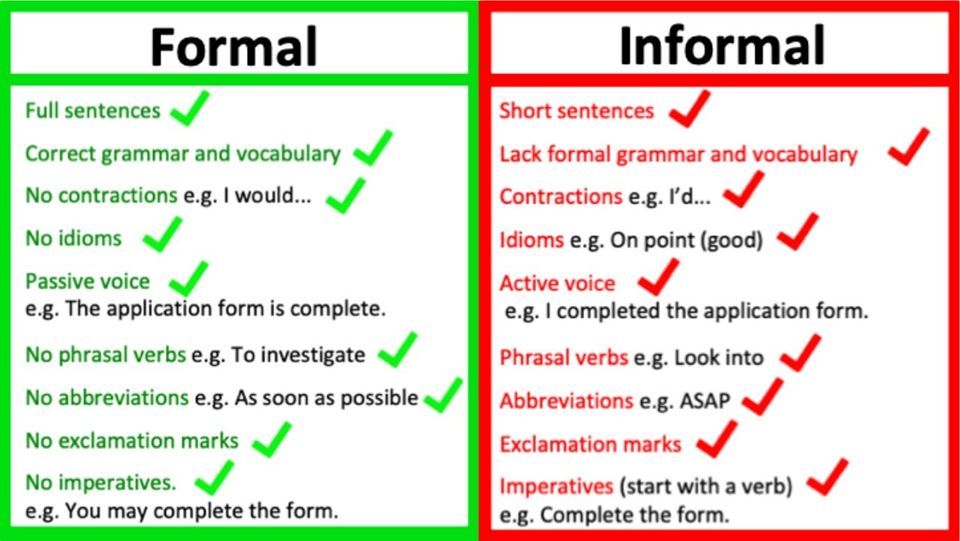

6 cases where you confuse a dash with a hyphen. But there will no longer be

"Es" as a dollar, "ve" as a tick, and instead of a dash or hyphen - "dash" or "minus". Well, I do not! In the new issue of "Literacy" we will learn to call a spade a spade. Or rather, let's deal once and for all with the insidious "features" and learn to distinguish them from each other. Go!

First, let's figure out how a dash and a hyphen differ in general. A hyphen usually separates parts of one word (“something”, “in English”), and a dash separates whole words and parts of a sentence (for example, as here or in the sentence “Summer is a small life”). Outwardly, a dash is longer than a hyphen, and in publishing there are even the concepts of "en dash" and "em dash". We, fortunately, do not need to think about the length of the dash, but being able to distinguish it from a hyphen is a must. nine0003

Outwardly, a dash is longer than a hyphen, and in publishing there are even the concepts of "en dash" and "em dash". We, fortunately, do not need to think about the length of the dash, but being able to distinguish it from a hyphen is a must. nine0003

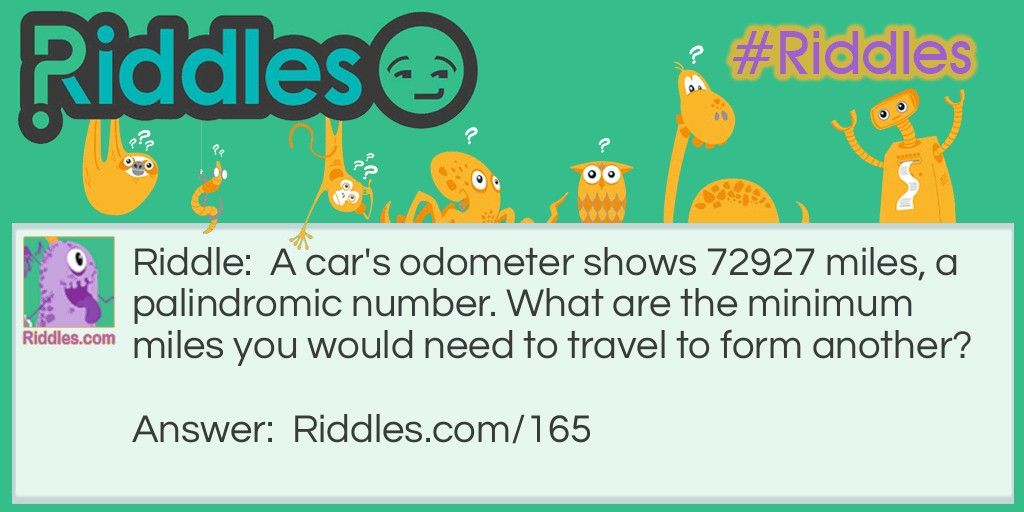

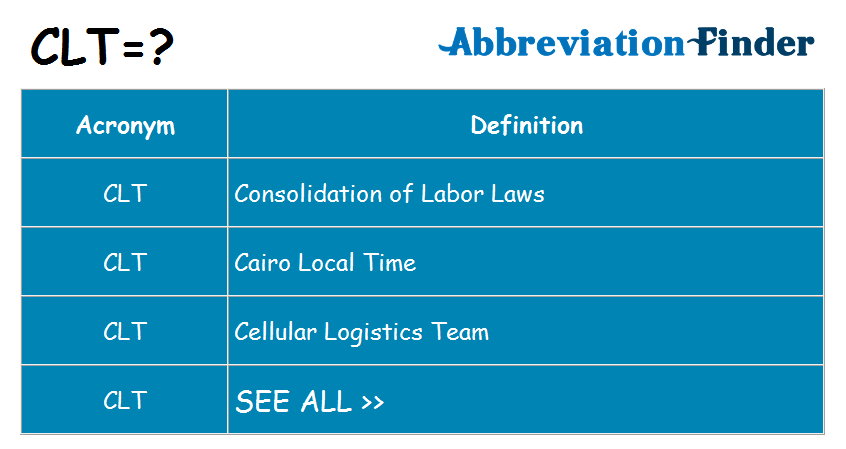

Let's start with the designation of time limits: if you see such a gap in a sentence, you should put a dash inside it, not a hyphen. For example, "vacation is scheduled for July-August", "2010-2016" (note that spaces before and after dashes are usually not put in the digital designation).

The same applies to the designation of quantitative limits: "I will be without communication for five to eight days." In this case and in the case above, the dash replaces the meaning of the words "from ... to". An important note in Rosenthal's reference book: if the union "or" can be inserted between two numerals, then they are connected by a hyphen: "We are going out of town for two or three days." But! With a digital designation, a dash is used again: “2-3 days”. nine0003

nine0003

Another case where a dash can easily be confused with a hyphen is such designations of spatial gaps. Even if we are not talking about a train to Vladivostok, which takes seven days, but about an electric train to Sergiev Posad (it declines that way!) - we use a dash and nothing but a dash.

To correctly write the name of this physical law from a school course, it is not necessary to remember its essence. It is enough to know that Joule and Lenz are two different people, and not the double surname of one scientist. What we are getting at: if you see several proper names, after which teachings, scientific institutions, competitions or something else are named, you definitely need a dash. For example, Joule-Lenz law, Boyle-Mariotte law, Prader-Willi syndrome. nine0003

Just don't confuse the surnames of some greats with the double surnames of others! In the case of Rimsky-Korsakov and Saltykov-Shchedrin, we are still dealing with hyphens.

You may have already guessed why in the first case we put a hyphen in the name, and a dash in the second. But just in case, we'll tell you. In the first case, "2014" is an immutable application expressed in numbers that refers to a single word. In the second case, we already have a phrase, and the numbers refer to both words, so here a dash comes to the rescue. Such cases include combinations of "Bush Jr" and "George Bush Jr", "male taxi driver" and "male taxi driver". nine0003

But just in case, we'll tell you. In the first case, "2014" is an immutable application expressed in numbers that refers to a single word. In the second case, we already have a phrase, and the numbers refer to both words, so here a dash comes to the rescue. Such cases include combinations of "Bush Jr" and "George Bush Jr", "male taxi driver" and "male taxi driver". nine0003

You probably never thought about what kind of "dash" is used in the enumeration - after all, it is almost impossible to make a mistake in the letter here. But now you will know for sure that it is still a dash!

Hyphenated patronymics will now be allowed in Kazakhstan | SOCIETY

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

883

nine0002 open source Almaty, December 3 - AiF Kazakhstan.

Such a change was made to the Code "On Marriage (Matrimony) and Family"

Previously, the Code stipulated that a child's patronymic is assigned only by one of the father's names or in a single spelling of both names.

Article 63 “The child's right to a given name, patronymic and surname” now reads as follows:

2. A child's name is given by the parents with their consent or by other legal representatives of the child. Patronymic at the request of parents or other legal representatives is assigned by the name of the person indicated by his father. nine0003

It is allowed to assign a double name when written separately or through a hyphen, but not more than two names. In the case of a double name for the father, it is allowed to assign a patronymic to the child by the double name of the father, by one of them, or in the continuous spelling of both names of the father.

When a father changes his name, the patronymic of his minor child changes, and the patronymic of an adult child - when he submits an application about it.