How to help your child with school projects

where to draw the line

“You have to write about cannibalism!” I fume at Zenobia, my fifth grade daughter. “Your teacher, your classmates, everybody wants to hear about people eating people.”

She’s constructing her big social studies report. Zenobia’s decision — all on her own — is to create a multimedia triptych on the Donner Party, the horror show where settlers get stuck in the Sierra snow, starve, and then snack on each other to survive. I am thrilled. My wife is the tutor in math, writing, science, piano, singing, Spanish… everything but history. That is Daddy’s domain.

“Don’t tell me how to do it,” my stubborn angel pouts. “You can help just a tiny bit but don’t boss me around.”

I know a distasteful amount about this historical event, and I am determined to share that knowledge with my daughter.

And I’m sure that at this very moment, most of the dads in my daughter’s class are crafting their child’s project into an A+. At last month’s science fair, my daughter entered a genius display of electricity in citrus fruit. I thought it was a sure-fire Alameda County winner, but no trophy came home. No blue ribbon, no scholarship to MIT. Our daughter’s project was totally overlooked, and out-done, frankly, by exhibits that look suspiciously like they were created by Tiger Dads who pulled all-nighters in an engineering lab to help their spawn win.

If other parents are helping, don’t I have to help to keep my daughter in the race for college?

Homework help that hurts

Ironically, I have my own big project: a reported essay on how much parents should help with their kids’ big reports. I call Carol Dweck, Ph.D., at her Stanford University office. She’s a top-notch psychology researcher, and the author of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Frankly, I expect her to tell me it’s important for parents to assist their kids on complicated projects, which would give me a green light. But her advice is the opposite.

“Parents can be available as a resource,” Dweck says, “to discuss the nature of the assignment, be a sounding board for ideas, and reflect back to the children what they are hearing. ”

”

“But that’s it,” she adds. “Helping too much with a big project sends a bad message that the child is not capable, and the child will doubt their own abilities. These are the kids who never gain confidence.”

So I shouldn’t encourage Zenobia to flesh out her report with meaty details? It’s hard to resist — she’s omitting the most interesting part of the story. Ignoring Dweck’s advice, I prod my daughter, “Your painting of the wagon train crossing the Wasatch Range is wonderful. But then… all you have for the final tragic weeks is a timeline… with meals excluded?”

Zenobia frowns as she glues a small tree on the horizon. “I’m reporting on westward expansion,” she sniffs in a patronizing tone. “The Donner Party was just like 500,000 other pioneers. Except for the eating.”

“Exactly!” I crow. “Don’t you want an A? This display of yours takes all the guts out of the story.”

The fine line between supporting and helping

Put off by my daughter for the moment, I return to my own project. This time, it’s “The Dad Man” Joe Kelly, author of six parenting books, who tells me to back off.

This time, it’s “The Dad Man” Joe Kelly, author of six parenting books, who tells me to back off.

“It’s more important to ‘support’ your child than to ‘help’ them,” Kelly says. “Supporting them means listening to them, responding to the struggles they’re having, but not doing the project for them.”

Diane Divecha, development psychologist and research affiliate of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, agrees. “Helping too much undermines a kid’s intrinsic motivation, undermines confidence, undermines skill development,” she says.

Next, I ask the million-dollar question: “When does acceptable ‘support’ cross the line into forbidden ‘help’?”

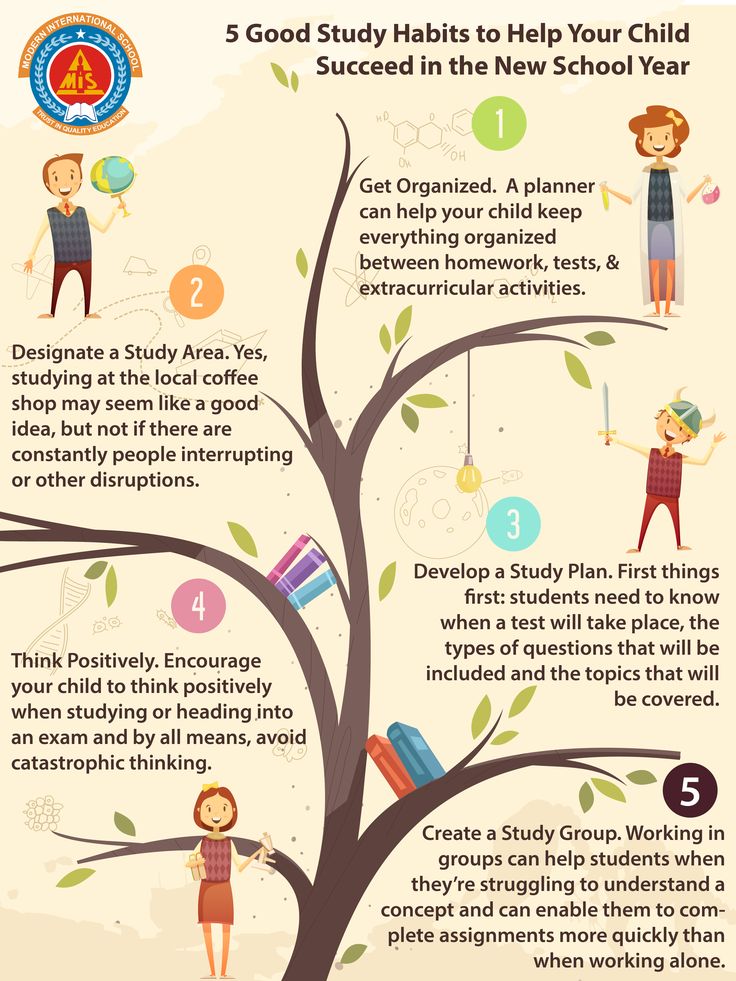

Support, Divecha explains, is helping kids develop the skills to do their own projects. “Help with the process. Teach them organizational skills. Have them make a to-do list, a materials list, a step-by-step timeline. Teach them time management. Teach them how to cut back on the project, if necessary. Teach them how to use the components [tools, supplies] needed to do the project. Teach them how to manage their feelings. Kids experience a lot of fear and stress doing big projects.”

Teach them how to manage their feelings. Kids experience a lot of fear and stress doing big projects.”

Think of it this way, says psychologist John Duffy, author of The Available Parent, “Your child should always be the one in charge of their school projects and papers, acting as ‘general contractors’, so to speak. The parent is in the role of consultant.”

If you find yourself directing the project, you’ve likely crossed the line from supporter into helper — which, big picture, is no help at all.

But all the other parents are doing it!

Experts say kids should do these projects themselves. But I know other parents are helping, which creates a vicious cycle that many parents get caught up in — even if they later regret it. Erica Benson of Piedmont, CA admits helping her son with his big project in fifth grade, too. “He says he learned a lot,” she muses, “but I didn’t like it at the end. Too much me, not enough him.”

When I express my concern that other parents are helping their kids, “The Dad Man” Joe Kelly reminds me that the main point of these projects is learning. “What your child learns is more important than the grade they get.”

“What your child learns is more important than the grade they get.”

But many parents — like me — and like Alisha Allen of Henderson, NV, can’t pretend that grades don’t matter. “I also helped,” she admits, “because it’s three-fourths of her grade … I would love it if she gets an A. [If she got] a C, I would be disappointed.”

And what about parents — like me — being their child’s first and most important teachers? Don’t I have the responsibility as Dad to make sure my daughter receives the full benefit of my extensive knowledge of the Donner Party’s harrowing migration?

“Zenobia,” I offer, trying a new approach, “did you know many people in the Donner Party were so starved they became mentally ill and near blind?”

She ignores me.

“Oddly enough,“ I continue, hopefully, “one child, William Hook, died — after he was rescued. He fatally gorged himself to death in Bear Valley.”

“Oh.” Zenobia replies.

Finally, one of my teacher friends drives the point home: parent “help” can actually do more harm than good.

“I had students writing the entire essay in class to avoid parents helping too much,” Heather Poland, a retired middle school teacher in San Diego, CA, writes me via Facebook. I realize my daughter’s school has implemented a similar practice for essays.

Finally I get it. I’ve been part of the problem. I consider one of Dr. Divecha’s last nuggets of advice: children model their behavior after their parents. This means it’s supportive and valuable to show them how to structure and complete a project.

I glance over at Zenobia. Her concentration on her project is intense.

“I was assigned an article to write, Zenobia,” I say. “It’s a medium-sized project, for a grownup. To do the project, I researched online, I interviewed experts, I thought of an amusing structure. My approach connected me emotionally and personally to the assignment. I outlined it, I started writing it, I rewrote it, and just now, I thought of a conclusion, and… guess what, Zenobia?”

“What?”

“I just finished. ”

”

Help Your Child Get Organized (for Parents)

Most kids generate a little chaos and disorganization. Yours might flit from one thing to the next — forgetting books at school, leaving towels on the floor, and failing to finish projects once started.

You'd like them to be more organized and to stay focused on tasks, such as homework. Is it possible?

Yes! A few kids seem naturally organized, but for the rest, organization is a skill learned over time. With help and some practice, kids can develop an effective approach to getting stuff done.

And you're the perfect person to teach your child, even if you don't feel all that organized yourself!

Easy as 1-2-3

For kids, all tasks can be broken down into a 1-2-3 process.

-

Getting organized means a kid gets where he or she needs to be and gathers the supplies needed to complete the task.

-

Staying focused means sticking with the task and learning to say "no" to distractions.

-

Getting it done means finishing up, checking your work, and putting on the finishing touches, like remembering to put a homework paper in the right folder and putting the folder inside the backpack so it's ready for the next day.

Once kids know these steps — and how to apply them — they can start tackling tasks more independently. That means homework, chores, and other tasks will get done with increasing consistency and efficiency. Of course, kids will still need parental help and guidance, but you probably won't have to nag as much.

Not only is it practical to teach these skills, but knowing how to get stuff done will help your child feel more competent and effective. Kids feel self-confident and proud when they're able to accomplish their tasks and responsibilities. They're also sure to be pleased when they find they have some extra free time to do what they'd like to do.

From Teeth Brushing to Book Reports

To get started, introduce the 1-2-3 method and help your child practice it in daily life. Even something as simple as brushing teeth requires this approach, so you might use this example when introducing the concept:

Even something as simple as brushing teeth requires this approach, so you might use this example when introducing the concept:

- Getting organized: Go to the bathroom and get out your toothbrush and toothpaste. Turn on the water.

- Staying focused: Dentists say to brush for 3 minutes, so that means keep brushing, even if you hear a really good song on the radio or you remember that you wanted to call your friend. Concentrate and remember what the dentist told you about brushing away from your gums.

- Getting it done: If you do steps 1 and 2, step 3 almost takes care of itself. Hurray, your 3 minutes are up and your teeth are clean! Getting it done means finishing up and putting on the finishing touches. With teeth brushing, that would be stuff like turning off the water, putting away the toothbrush and paste, and making sure there's no toothpaste foam on your face!

p

With a more complex task, like completing a book report, the steps would become more involved, but the basic elements remain the same.

Here's how you might walk your child through the steps:

1. Getting OrganizedExplain that this step is all about getting ready. It's about figuring out what kids need to do and gathering any necessary items. For instance: "So you have a book report to write. What do you need to do to get started?" Help your child make a list of things like: Choose a book. Make sure the book is OK with the teacher. Write down the book and the author's name. Check the book out of the library. Mark the due date on a calendar.

Then help your child think of the supplies needed: The book, some note cards, a pen for taking notes, the teacher's list of questions to answer, and a report cover. Have your child gather the supplies where the work will take place.

As the project progresses, show your child how to use the list to check off what's already done and get ready for what's next. Demonstrate how to add to the list, too. Coach your child to think, "OK, I did these things. Now, what's next? Oh yeah, start reading the book" and to add things to the list like finish the book, read over my teacher's directions, start writing the report.

Now, what's next? Oh yeah, start reading the book" and to add things to the list like finish the book, read over my teacher's directions, start writing the report.

Explain that this part is about doing it and sticking with the job. Tell kids this means doing what you're supposed to do, following what's on the list, and sticking with it.

It also means focusing when there's something else your child would rather be doing — the hardest part of all! Help kids learn how to handle and resist these inevitable temptations. While working on the report, a competing idea might pop into your child's head: "I feel like shooting some hoops now." Teach kids to challenge that impulse by asking themselves "Is that what I'm supposed to be doing?"

Explain that a tiny break to stretch a little and then get right back to the task at hand is OK. Then kids can make a plan to shoot hoops after the work is done. Let them know that staying focused is tough sometimes, but it gets easier with practice.

Explain that this is the part when kids will be finishing up the job. Talk about things like copying work neatly and asking a parent to read it over to help find any mistakes.

Coach your child to take those important final steps: putting his or her name on the report, placing it in a report cover, putting the report in the correct school folder, and putting the folder in the backpack so it's ready to be turned in.

p

How to Start

Here are some tips on how to begin teaching the 1-2-3 process:

Introduce the Idea

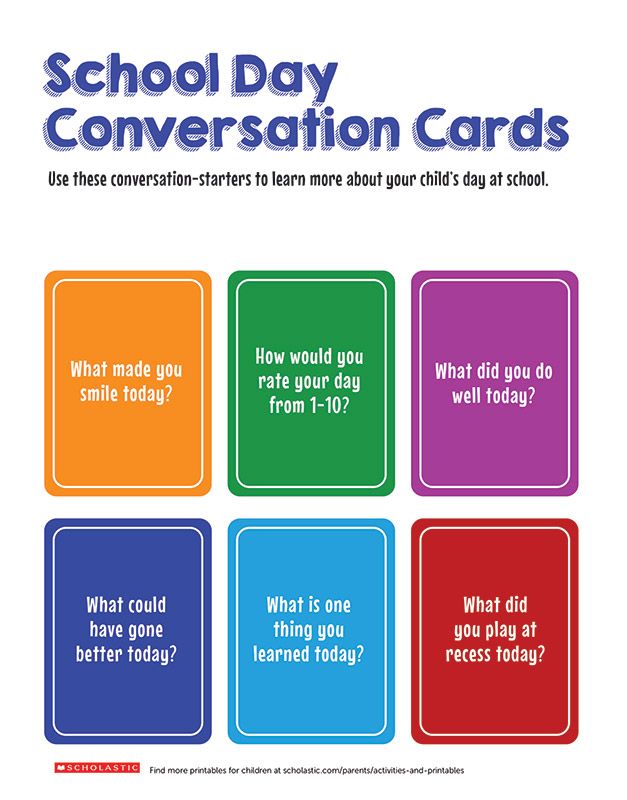

Start the conversation by using the examples above and show your child the kids' article Organize, Focus, Get It Done. Read it together and ask for reactions. Will it be easy or hard? Is he or she already doing some of it? Is there something he or she would like to get better at?

Get Buy-In

Brainstorm about what might be easier or better if your child was more organized and focused. Maybe homework would get done faster, there would be more play time, and there would be less nagging about chores. Then there's the added bonus of your child feeling proud and you being proud, too.

Set Expectations

Be clear, in a kind way, that you expect your kids to work on these skills and that you'll be there to help along the way.

Make a Plan

Decide on one thing to focus on first. You can come up with three things and let your child choose one. Or if homework or a particular chore has been a problem, that's the natural place to begin.

Get Comfortable in Your Role

For the best results, you'll want to be a low-key coach. You can ask questions that will help kids get on track and stay there. But use these questions to prompt their thought process about what needs to be done. Praise progress, but don't go overboard. The self-satisfaction kids will feel will be a more powerful motivator. Also, be sure to ask your child's opinion of how things are going so far.

Start Thinking in Questions

Though you might not realize it, every time you take on a task, you ask yourself questions and then answer them with thoughts and actions. If you want to unload groceries from the car, you ask yourself:

- Q: Did I get them all out of the trunk?

A: No. I'll go get the rest. - Q: Did I close the trunk?

A: Yes. - Q: Where's the milk and ice cream? I need to put them away first.

A: Done. Now, what's next?

Encourage kids to start seeing tasks as a series of questions and answers. Suggest that they ask these questions out loud and then answer them. These questions are the ones you hope will eventually live inside a child's head. And with practice, they'll learn to ask them without being prompted.

Work together to come up with questions that need to be asked so the chosen task can be completed. You might even jot them down on index cards. Start by asking the questions and having your child answer. Later, transfer responsibility for the questions from you to your child.

p

Things to Remember

It will take time to teach kids how to break down tasks into steps. It also will take time for them to learn how to apply these skills to what needs to be done. Sometimes, it will seem simpler just to do it for them. It certainly would take less time.

But the trouble is that kids don't learn how to be independent and successful if their parents swoop in every time a situation is challenging or complex.

Here's why it's worth your time and effort:

- Kids learn new skills that they'll need — how to pour a bowl of cereal, tie shoes, match clothes, complete a homework assignment.

- They'll develop a sense of independence. Kids who dress themselves at age 4 feel like big kids. It's a good feeling that will deepen over time as they learn to do even more without help. From these good feelings, kids begin to form a belief about themselves — "I can do it.

"

- Your firm but kind expectations that your kids should start tackling certain jobs on their own send a strong message. You reinforce their independence and encourage them to accept a certain level of responsibility. Kids learn that others will set expectations and that they can meet them.

- This kind of teaching can be a very loving gesture. You're taking the time to show your kids how to do something — with interest, patience, love, kindness, and their best interests at heart. This will make kids feel cared for and loved. Think of it as filling up a child's toolbox with crucial life tools.

Fresh number

RG -week

Rodina

thematic applications

Union

Fresh number 9000

Society

Aleksey Duel

A child comes home from school and says that in a week the teacher is waiting for him to submit a project. What it is? It seems that at the beginning of the year something was said about these projects at the parent meeting, but then, during the current affairs with spelling and division with a remainder, everyone forgot about it. Yes, and at work there are enough of their own - real - projects, what else is school? Olga Uzorova, the author of federal textbooks, primary school methodologist, told PROparent about what kind of animal this most unknown “school project” is and how to deal with it.

Don't panic!

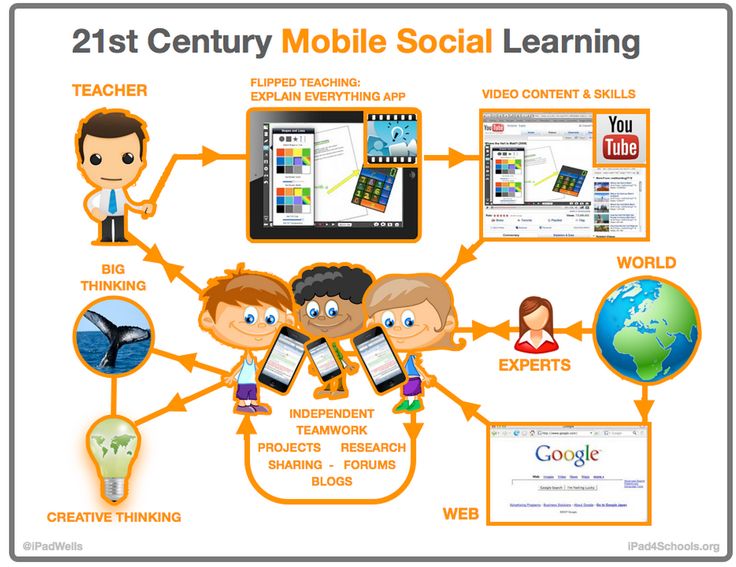

The current school projects, provided for by the federal standard of elementary school, are, in fact, the reincarnation of "student reports", which were prepared by the parents themselves in the junior and middle grades. Since it was in the pre-computer era, they wrote with a pen on paper. Now in the classrooms there are electronic boards, projectors and other equipment that allows you to replace reading on a piece of paper with a story, accompanied by a beautiful illustrative series.

- A school project is very similar to research, but originality or any practical conclusions are not required here, explains Olga Uzorova. - It is enough to consider the object from different sides, although if you manage to find out something new, it will be even better.

Ask a teacher

Although student projects have been introduced everywhere and have become mandatory for everyone, no one knows exactly what a student should present. Requirements depend on teachers, school administration, regional methodological centers. Therefore, in order not to put the child in an awkward position, it is worth agreeing with the teacher on the topic, content and requirements for the design of the project.

- Somewhere from a second grader they expect four or five pages of text, and somewhere - at least fifteen, - shares Olga Uzorova. - In addition, the teacher should then submit the best projects of their students to the competition. Because of this, he may ask, for example, to use more video. Or focus on infographics - teachers are usually hinted at which works will be highly appreciated by the jury members at the next stage.

Choose a topic

The teacher can suggest it, or you can formulate it yourself. In order not to rack your brains, you should search the Internet - they are often posted by active teachers. For example, here or here. But you can show your imagination yourself. The most important thing is not to get carried away, the project is still for children and, in theory, should be completed by the child himself. Therefore, the problems of quantum mechanics, probably, should not be taken. But, let's say, "The best model of a paper boat" is quite suitable.

Reason for communication

- The project is a new genre, few people understand it, and even more so - they know how to do it, - Olga Uzorova honestly admits. - Therefore, it is often done like this: mom sits down at the computer, retypes or copies a few pages from a high school textbook or Wikipedia, attaches an introduction and conclusion, finds a couple of illustrations and copies to a USB flash drive. And the student can only memorize his short speech. This strategy usually gets you a good grade, but it's really only a last resort. By doing this, parents deprive their child of the opportunity to learn at least a little bit to think independently, from the elementary grades they are taught to deceive and simulate learning.

In fact, the work on a school project that has fallen on the whole family is a wonderful opportunity to communicate with the child and do a common thing together. Naturally, it is impossible to leave the student alone with this task. Without methodical and organizational guidance, technical assistance from parents, he is unlikely to be able to do anything himself. But when preparing a project, the student must be entrusted with a separate front of work, clearly set the task and allow him to take on part of the intellectual work.

Help, but do not scold

If the project involves practical work, it should be entrusted to the student: it is the most interesting. Help to prepare an experiment, observation, experiment. But here one must be prepared for the fact that Murphy's law will be confirmed: "Any, even the most precise indication, will be understood exactly the opposite."

- It is very important that parents do not scold the child for failures or mistakes in the preparation of the project, Olga Uzorova insists. - Otherwise, he may lose motivation for any creative or analytical work forever. Restrain yourself, do not lay problems for yourself in the future.

Don't grumble!

- It is clear that projects in their current form are not the most successful option for schoolchildren, besides, tired parents usually have to take the rap for their children, - Olga Uzorova regrets. - But, nevertheless, please never say anything out loud that could form a child or betray your own negative attitude towards this work. If you want to express dissatisfaction - do it in the evening in the kitchen. Or switch to a foreign language. Even with a not very successful task setting by the teacher, this work can and should be interesting. But she will become so only on one condition - if the whole family perceives her not as a burden, but as an opportunity to show her abilities.

Children's championship

Initially, it was assumed that the students themselves would be involved in the projects first of all. But in reality, it turned out that while individual non-lazy and inquisitive schoolchildren pore over their work, the rest of the parents do all the work. It is clear that a person who has become adept at writing essays, term papers, diplomas and service reports over a long life will make a much smoother and more "presentable" project than an honest but inexperienced second grader. As a result, those few who do everything honestly find themselves in a deliberately losing situation.

- This is a vicious practice - this is how children get their first experience of hack work, - explains Olga Uzorova. - Therefore, try to make sure that this is a student project. It is clear that it is much easier to do it yourself than to help the child, organize it and explain all the details. But let's at least strive to ensure that the project competition is specifically for children.

EducationProParent

The main thing today

-

Seismologist Hugerbits, who predicted the tragedy in Turkey, predicted a mega-earthquake in March

-

Vučić said that Western leaders confessed to him their participation in the conflict in Ukraine

-

The head of Chechnya, Kadyrov, announced the taking of fortifications of the Armed Forces of Ukraine in the Kremennaya area

-

The Ministry of Labor proposed to increase social pensions by another April 3 3 percent

-

Putin signed the law on the protection of the Russian language

How to help a child complete a project? What can not be done? | Article on the topic:

How to help a child make a project? What can not be done?

For parents who want their children to participate in project activities, it is very important to determine what kind of work their child is ready for, what he can and wants to do. Often, the project work is completely carried out by the parents themselves, and then their confused and frightened child, worried and, with difficulty understanding what adults have written for him, defends such a (alien to himself) project at the commission or reads it to the class in the form of a report.

Parents do this out of good intentions, believing that the child, after watching how mom or dad do a project, will become interested, carried away by their ideas, and will gain experience in project activities using the example of their parents' work.

The result of such work is not needed, not useful, not interesting either to the child himself or to those who are forced to listen to his speech. And for a child, such an experience is rather even harmful: passing off someone else's work as his own, other people's ideas as his own, he learns from childhood to deceive himself and others and is not busy with what he really would like and could do.

In our school childhood there were no projects, so many parents do not yet understand what it is and what it is for. There is a danger of turning a project (especially a research project) into a report or abstract that we once wrote in school.

To decide whether a child should now be involved in a project and which project to choose, you need to understand what a school project is?

Here is the definition of the term "project" you will find on Wikipedia:

the essence of the idea and the possibility of its practical implementation.

A project is works, plans, activities and other tasks aimed at creating a unique product (devices, works, services). The execution of the project constitutes the project activity…”

So, if your child is passionate about some idea, if he has some idea (invent a perpetual motion machine, design a flying car, organize a cafe for stray dogs, sew a queen's dress for the new year, make a new design of his room , collect a collection of precious stones, print your collection of poems), welcome to project activities!

The topic of the project should not be proposed by parents. The project should be what the child is currently interested in and doing.

Pay attention to what your child does in his spare time, what he is interested in, what problems he is concerned about, what questions he asks you. When choosing the direction of project activity, do not start from your interests and ideas, but from the child.

The topic of the project is chosen and formulated by the author himself!

Do not force your child into scientific activities. Or maybe he is not a scientist at all, but a poet or an artist? Let him be!

How many newly-minted candidates and even doctors of sciences are now, who, in fact, are not scientists, have not offered anything new to this world, have not made any scientific discoveries, but have scribbled a huge number of fake dissertations - plagiarism and compilations of other people's works. These people imitate scientific activity all their lives and even have the courage to make presentations at international scientific conferences where real scientists come. Maybe if these pseudo-scientists had once correctly chosen the direction of their activity, they would have benefited people and themselves would have been happy in another profession.

Today, scientific degrees are depreciating. Now even boxers defend dissertations. It is not clear why this is necessary? These people would earn more respect for themselves in society, would bring more benefits and get more satisfaction if, for example, they organized and led a children's sports school. Why not a project?

Many children finishing the 11th grade cannot decide on their future profession, do not know where to go or are not sure of their choice. Often this choice is made for them by their parents, guided by practical considerations and their own interests.

The task of the project activity is to create conditions in which the child will develop his own unique abilities, realize his own ideas, help the little person find himself. Then it will be interesting for him to live and work!

The project must have some kind of end result: the “final product”. It can be material: a drawing, a model, a layout, a film, a book, a computer presentation, a painting, a sculpture, an illustrated album, a magazine, a newspaper, etc.; effective: exhibition, excursion, hike, concert, performance, holiday, quiz, etc., written: article, brochure, bill, instruction, recommendations, business plan.

Depending on the activity the child is engaged in, the project can be: practical, research, creative, informational, playful.

A practical project involves a specific, final result, which can then be used in real life by the author of the project or other people.

A research project is like a scientific study. The author must substantiate the relevance of the chosen topic, set the goals and objectives of the study, put forward hypotheses, test various versions, conduct experiments, experiments, and analyze the results.

A creative project involves an unconventional, free approach to its implementation. It is impossible to clearly plan all the stages of work on such a project in advance. The direction of work depends on the flight of imagination and creativity. You can pre-plan the desired end result of such a project (video film, expedition ...).

The information project is aimed at collecting information, data, facts about any object or phenomenon. The collected information is checked, analyzed and summarized. As a result, reliable information is presented to a wide audience.

Game project. Here, the participants take on various roles (literary, fairy tale or fictional characters) and imitate social or business relationships in a situation given by the authors. Situations are invented in accordance with the theme and objectives of the project. The degree of creativity in such a project is very high. The main activity of such a project is gaming.

According to the number of participants, the project can be individual, pair and group.

Projects can be short-term, long-term (one year, two years). Maybe a mini-project - for one lesson or part of the lesson.

Let's continue reading the definition of the term "project". So: “The implementation of the project is a project activity, which includes: conducting management activities (project management) ...” This is the part that parents and the teacher can safely take on!

After the child has chosen the topic of the project, it is necessary to offer him:

- Determine the goals of his work (why he will do it, what he wants to get as a result). If this is a research project, the child should think about what questions on this topic he would like to find answers to, think over the answers to the questions posed.

- Decide where (or how) he will look for answers to the questions. Determine how to collect the necessary information.

- Work with sources of information, find answers to your questions and draw conclusions.

- Submit the results of your work.

- Determine how the results will be presented (project form). Prepare a short presentation to present your research to the audience.

- If the project is being done in a group, it is necessary to distribute tasks (duties) among the members of the working group.

As well as scientific, project work has rules for registration. A person can have many interesting ideas and undertakings, but if he does not learn how to properly format and present his work and his ideas, no one will ever know about them.

Parents can help their child get their project right. Later, he will learn how to correctly present his work and will do it on his own.

The rules for designing a project are called the “passport of project work”.

As a rule, the design work passport consists of the following items:

- Project name.

- Author of the project or composition of the project team (full name of students, class, school)

- Project manager.

- Academic disciplines close to the topic of the project.

- Project type (practical, research, creative, informational, playful.