How to help an adult child

Have adult kids? Here's how to support without overstepping.

Last year we published a piece called Adult Children: The Guide to Parenting Your Grown Kids. Many readers responded by sharing their intensely difficult situations with adult children. Comments included everything from financial challenges to “sudden flights from the nest,” disagreements with spouses about family dynamics, concerns about mental health, disappointments about career paths and more. And these struggles and heartbreaks are often magnified when grandchildren come into the picture.

Numbers Rise, Roles Change: A Profile of Modern Grandparents

First, let’s look at the numbers. In 2014, Census data reported a total of 69.5 million US grandparents, up from 65.1 million in 2009. And as more boomers become grandparents, the tally will likely surpass 70 million.

According to a 2018 survey by AARP, one in 10 grandparents live in the same household as their grandchildren. Five percent of those grandparents serve as their primary caregiver. One in 10 grandparents takes care of their grandchildren by babysitting. And many grandparents provide financially for their grandchildren—like gifts to help with daily costs and educational support.

But what’s the biggest challenge facing today’s grandparents? Disagreements with their own adult children over parenting styles. The AARP survey supports this divide. Their results reported a majority of grandparents “view their parenting style to be superior to parents of today.”

Juxtaposed with the happy reality of grandparents living longer, healthier lives—which allows them to have longer relationships with their grandchildren than previous generations—these differing views can result in frustration, tension and even total estrangement.

While every situation is unique and the answers are not always cut and dry, we’ll offer five ways to support your children and grandchildren.

5 Ways to Be a Supportive Parent and Grandparent

Knowing when to step back and when to step in is tricky. Here’s how both industry experts and experienced grandparents recommend staying involved without going too far.

Here’s how both industry experts and experienced grandparents recommend staying involved without going too far.

1. Discuss Expectations and Pain Points with Your Partner

While you might not always agree with each other on methods, it’s important to listen to your spouse and hear them out. This is especially important in blended families, when the adult child is from a spouse’s previous marriage. You’ve committed to grandparenting and parenting your adult children together, so you both get a say in the way you engage with your families.

Choose a time to sit down and talk about the kids and grandkids—even if you’ve never done it before. Talk about your hopes, desires and fears about parenting and grandparenting. Be open and honest about your expectations. Talk about the things you’re struggling with in the relationships with your kids. Let them know about the ways you feel rejected or how you don’t want to be last on the list. Talk to them about how you hate watching them struggle and just want to intervene.

Discuss the things that bother you about your kids’ parenting styles, but also celebrate the things they’re doing well. Maybe your husband hates the way your son talks to you, but he doesn’t understand your history. By getting on the same page as much as possible, you’ll be able to face challenges and conflicts as a team and prevent divisions among children and grandchildren.

2. Understand Where They’re Coming From

You can respectfully disagree with your adult kids about their parenting style, approach to discipline, and general lifestyle differences, but listen to their reasoning and try to understand it.

Sometimes, the differences in parenting styles seem more drastic than they actually are. Parenting is a sensitive issue and an emotionally charged one. Keep this in mind: Your child may be struggling with parenting because of differences in how a spouse was raised.

Perhaps you offered to help with cleaning your daughter’s house while she’s at work and your grandson is napping. While she might be used to your style of cleaning, her husband was frustrated when he couldn’t find things where he’d left them (and he may have grown up in a home where things weren’t always neat and tidy). Instead of throwing your hands up in defeat, suggest something else. Maybe you can help with meal prep, laundry or cleaning windows and floors.

While she might be used to your style of cleaning, her husband was frustrated when he couldn’t find things where he’d left them (and he may have grown up in a home where things weren’t always neat and tidy). Instead of throwing your hands up in defeat, suggest something else. Maybe you can help with meal prep, laundry or cleaning windows and floors.

Another example: maybe your son prefers your approach to discipline over his partner’s (she may have grown up in a home with a more relaxed way of managing behaviors). Steer clear of taking sides or pushing your agenda, as this can drive a wedge in their relationship. It could also lead them to reject your help with childcare. This doesn’t mean you have to let your granddaughter run the show when you’re there, but be careful not to override her parents’ wishes—or undermine their authority—when it comes to discipline.

3. Ask Your Kids What They’d Find Most Helpful

Most parents want to help their children and grandchildren—no matter how old they are. And that’s OK! But as they grow, their needs change. Your way of helping should shift accordingly.

And that’s OK! But as they grow, their needs change. Your way of helping should shift accordingly.

It may take some time to find the best way to be helpful without interfering, hovering or enabling. Your adult child may be trying to assert themselves and claim independence, but if you’re always coming to his or her aid in the ways you think are best, you’ll delay that process. In other cases, your adult child is so independent you may think they don’t need you at all. But they may just need your help in other ways.

Initiate conversations with the goal of helping without hindering. For example: “What’s the hardest part of your parenting day?” If your daughter says bedtime, offer to help put your granddaughter to bed once a week. Or bring her to your home for a sleepover.

If they’re struggling with a co-worker or boss, get their take on what might help. Be a listening ear instead of taking a “you shouldn’t talk to him like that” tone. Share the ways you dealt with a difficult boss, or what worked for you in a frustrating co-worker relationship.

Take it a step further: ask your children for their opinions and advice, says Tina B. Tessina, Ph.D., psychotherapist and author of The Ten Smartest Decisions a Woman Can Make After Forty. “Even in early childhood, children can be encouraged to develop their own opinions about events and decisions you face as a family; as they get older you can ask for their ideas about what to do,” says Tessina. “When your children become adults, you can request advice about work issues, investments or other concerns. Sharing advice as friends and equals will create the friendly connection you want,” she says.

4. Accept That Your Adult Children Can Think for Themselves

“When I had my first grandkid, I remembered having an argument with my son about how they were spoiling him too much, and he kept on insisting he wasn’t doing so,” says Ricardo Flores, whose eldest son is 33.

“It went on and on and we almost ruined Thanksgiving, but then we decided to talk it out and that’s when I learned that we are in different generations now, and what worked for me as a parent in the past might not be the best thing to apply to today’s generation,” says Flores, a financial advisor at The Product Analyst.

“Since then, I learned to keep my boundaries as a grandparent and let my son do the parenting for his kid, because it’s also how I would want it for myself,” he says. “The point is that we as parents should understand that our kids will grow, and the time will come when they stop asking for us—and eventually, their kids will ask for them.”

It can be difficult to build good and harmonious relationships with your children because they will make different choices, says Flores. “But you have to accept that they can think on their own already. Children don’t stop becoming our children, and parenting does not stop the moment they become adults. There will always be differences, and we must learn to accept and adapt to that.”

5. Focus on the Things You Can Contribute

You see your grandson struggling with a lack of structure. You’ve tried confronting your son and daughter-in-law about it, and it only leads to harsh words and hurt feelings. But that shouldn’t stop you from having a healthy relationship with your grandson.

When he comes to your house or you take him out somewhere, find ways to give him the structure he needs without making a big show of it or throwing his parents under the bus. For example, say this: “I made a picture schedule of what we’re doing today!” not this, “Since your mom never has a plan, I took charge and made this list.”

Maybe you have strict instructions on the “don’t dos” from your kids, and it makes you feel limited as a grandparent. All is not lost. Think about what your grandkids love and what makes them tick. Focus on cultivating those hobbies and engaging them in their interests. Leave your frustrations about your adult child out of the picture.

Share with your children on a parent-to-parent basis, suggests Tina B. Tessina. “If your children have children of their own, you have expertise they can benefit from, but be willing to learn from them as well,” says Tessina. “If they’re reading books or taking courses on parenting, discuss the information as you would with another parent your own age,” she says. “If they parent their children differently than you did, don’t take it as a personal affront, and don’t interfere unless you’re asked to.”

“If they parent their children differently than you did, don’t take it as a personal affront, and don’t interfere unless you’re asked to.”

How to Be a Supportive Parent of an Adult Child: Dating, Relationships and Money

Maybe there are no grandchildren in the picture yet, or maybe the struggles are less about the grandkids and more about your adult children’s relationship patterns or financial struggles. Here’s what worked for these parents:

Let Them Make Their Own Decisions

Nancy Burger, 59, is an experienced writer and author of the parenting book, A Special Kind of Brain. She’s struggled with finding the right balance in offering advice versus overstepping with her adult son and daughter. She’s especially had a hard time when it comes to their dating and relationships.

Her daughter, 23, recently started dating someone new. “Under normal circumstances, I wouldn’t ask many questions and would wait for her to share information as the relationship unfolds,” says Burger. “But given the ongoing risk of contracting COVID-19, I find myself keenly interested in the young man’s travel patterns and social circles.”

“But given the ongoing risk of contracting COVID-19, I find myself keenly interested in the young man’s travel patterns and social circles.”

What has worked for Burger? “The trick has been to inquire without sounding meddlesome or nosy, but instead, appealing to my daughter’s sense of responsibility,” she says. For example, when she recently mentioned a plan to join him on a trip to New York City to meet some of his friends, Burger asked her how she felt about the potential health risks, Burger explains. “She assured me that they would socially distance, that her risk of contracting the virus would be low.”

“While I was careful to acknowledge and validate her response, I added that I would not feel comfortable being in close quarters with her after a trip to the city and would feel compelled to maintain a two-week separation. This was unpalatable to her, and she decided not to go,” says Burger.

“By focusing my comments on my own experience and the boundaries I would have to set, I avoided directives about what she should or shouldn’t do,” Burger explains. “This is a subtle but powerful difference that allows our adult children to make informed decisions on their own.”

“This is a subtle but powerful difference that allows our adult children to make informed decisions on their own.”

Stay in Your Lane

Lizbeth Meredith, 55, is an author and probation supervisor from Anchorage, Alaska. “Overstepping is my middle name,” she says. “My oldest daughter turned 33 recently and asked that I not nag her for the entire day. I had no idea if we’d have anything to say,” Meredith says. As a single-mom, Meredith wrapped her entire life around her girls. “We had a lot of tragedy and hardships, but we kept moving forward,” she says. But when the girls grew up, Meredith felt like she was left behind. “But my therapist friend told me to visualize not driving in another lane. ‘Stay in your lane!’ she says. If only it were that easy.” Meredith wrote a funny essay published in the HerStories Project about Conscious Unhovering, which explained the pain of both sides—overstepping and staying in your lane. “I keep trying to do exactly that. And I’m doing better,” she says.

Pay Attention to the Balance of Your Interaction

As a parent, the role of nurturer and caretaker is familiar, and perhaps comfortable, for both you and your children, says Tina B. Tessina. But you don’t want to foster that relationship when your children are grown.

“Don’t let your part in the relationship slide into all giving (or all receiving),” she advises. “Remember, the objective is to create a friendship with your children. If your children always seem ready to take from you, make some suggestions of what they can do in return.”

More Resources for the Journey of Parenting Your Adult Kids

We know that navigating life with your adult children isn’t easy—but there is much joy to be found in being a parent and grandparent. That’s why we’ve created these guides to help you through this complicated stage of parenthood.

- Adult Children: The Guide to Parenting Your Grown Kids

- What to Do When Your Adult Kids Keep Fighting

- Who Will Care For My Special Needs Adult Child?

- Boomerang Kids: When Adult Children Move Back Home

- How to Embrace the Empty Nest

- Giving Money to Grown Children: When to Stop and How to Break the Habit

You’re not alone! Find comfort in community.

Tell us how you’ve handled a difficult situation as a grandparent or parent of an adult child. Share a question about how to better manage your role.

Tell us how you’ve handled a difficult situation as a grandparent or parent of an adult child. Share a question about how to better manage your role.

Say These Words to Help Your Struggling Adult Child Succeed

While you can't truly control the outcome of your adult child’s life, it is crucial for you as a parent of an adult son or daughter to do all you can to create optimal, facilitative conditions for their success. In plain English, do not send off negative messages, don't engage in fruitless power struggles, and stop your enabling of self-destructive behaviors.

For over 30 years, I have coached parents of struggling adult sons and daughters. My clients are domestic and international and from across the economic strata. Based on this experience, I feel very strongly that no matter how much your adult son or daughter is struggling, your role in how you perceive, feel, and respond are of utmost importance.

There are several behaviors that suggest an adult child is, in fact, struggling. These include:

These include:

- Embellishing and lying

- Expressing angry outbursts

- Slinging guilt

- Engaging in gaslighting

- Unfairly blaming their own struggles on you

- Remaining underemployed

- Acting manipulatively

- Poorly managed addictions

- Staying with emotionally abusive intimate partners

- Reckless spending

A Note to Adult Children Who May Be Reading This

Before I go further, let me say this: I realize that there are many toxic parents of adult children out there. If you are an adult son or daughter of toxic parents who traumatized you, I empathize. I have seen many adult children who have been mistreated and abused by their parents. And as a parent myself, I've made my own share of mistakes and could have done some things better. At the same time, there are countless parents who try their best while understandably falling far short of being perfect.

If you happen to be a frustrated adult child, please reclaim your value and stay mindful of it. But don't, or don't continue, to compromise your worth by riding on a horse named Victim and repeatedly heading off to that horrific rodeo of self-destructive wild and bucking rides.

But don't, or don't continue, to compromise your worth by riding on a horse named Victim and repeatedly heading off to that horrific rodeo of self-destructive wild and bucking rides.

And while I empathize if you have had problematic or even abusive parents, please don't blame them for your own struggles without also taking a look in the mirror. Ask yourself how you can move toward your own valuable independence. Bottom line: Learn to feel good about knowing your own value as an adult even if your parent(s) did not see it or express it.

Now back to the parents of struggling adult children...

Are You a Parent or a SWAT Team Leader?

I introduced the concept of parents of struggling adult children as SWAT team leaders in a past post. SWAT team parents are hypervigiliant in being on the lookout for crises in the lives of their adult children. This happens subconsciously as no morally intact parent intentionally thrives on their adult son or daughter going through highly stressful times. Yes, I realize that tragic things happen to all of us, such as sudden health issues, car accidents, or traumas of one kind or another. But what about those adult children who deliberately create crises? Parents of struggling adult children who behave this way often feel like they are on call—like being on a SWAT team. Are you confused about what I am referring tor? The parents I coach have shared being on the receiving end of high-impact stressors from adult children such as:

Yes, I realize that tragic things happen to all of us, such as sudden health issues, car accidents, or traumas of one kind or another. But what about those adult children who deliberately create crises? Parents of struggling adult children who behave this way often feel like they are on call—like being on a SWAT team. Are you confused about what I am referring tor? The parents I coach have shared being on the receiving end of high-impact stressors from adult children such as:

- A sudden crisis text or call demanding (or guilting) you to give them money because of their haphazard financial management.

- Harping on the past with a victim/"woe is me" mindset.

- Angrily lashing out at you with a failing short-term memory and forgetting all you've done for them in the past.

- Unfairly blaming you for not giving or doing enough compared to what you did/do for their siblings.

- Coming to you for support, complaining because they are with a toxic, manipulative relationship partner.

You rush in to be supportive, and then she or he goes back for more abuse from the toxic partner. Adding salt to your wound, they forget how supportive you've been and blame you for their relationship problems.

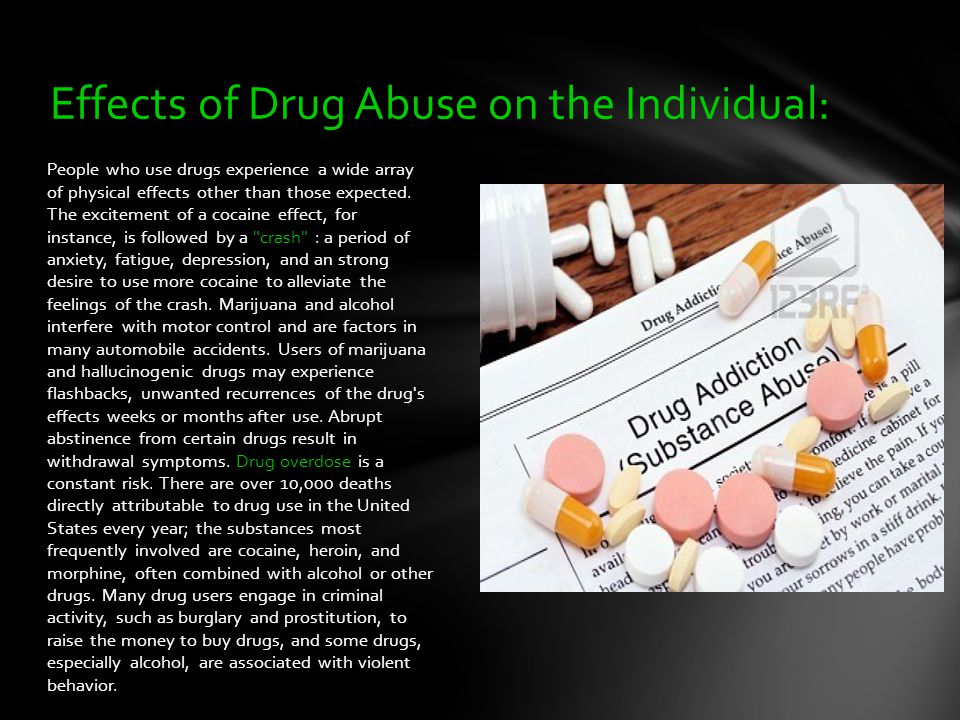

You rush in to be supportive, and then she or he goes back for more abuse from the toxic partner. Adding salt to your wound, they forget how supportive you've been and blame you for their relationship problems. - Being in denial about a substance abuse problem or outright addiction and blaming you for stressing them out and "making" them use alcohol or drugs.

- Neglecting your grandchildren and telling you to help (or letting you discover the issues) without being appreciative (e.g., "Don't you even care about your grandchildren?")

It's Time to Retire from the SWAT Team

I encourage you to shift from being crisis first responder to an emotion coach. Your struggling adult child is likely emotionally immature and needs you to coach him or her to handle emotions and communicate more effectively. The more you see yourself as your adult child's coach, the less you will feel stuck—or codependent—as a parent. These sample soundbites below reflect the calm, firm, non-controlling approach which I detail in my book 10 Days to a Less Defiant Child:

- “I hear that’s how you see it.

I see it differently. It may help us to move on if we agree to disagree instead of continuing to fight.”

I see it differently. It may help us to move on if we agree to disagree instead of continuing to fight.” - “I can see that you’re very frustrated. Just know I’m here for you if you’d like to talk.”

- “I hope that once we calm down, we will be able to have a constructive conversation about this.”

- “I can’t control the way you choose to speak to me [or your sibling, other parent, relative] when you are upset. I think you will feel better by being more respectful.”

- “It’ll work better for both of us if you can say what you mean without saying it meanly.”

- “There’s a reactive side of me, as your parent, that now wants to yell and get controlling. Just being aware and expressing this is helping me stay calmer. How about we talk this out so we can understand each other better?”

- “You know what you are doing right now is a really good example of you calming down even though I know you feel strongly about this. I really admire how you are able to keep your cool.

”

” - “The way you’re being flexible right now really impresses me.”

- “I appreciate how cooperative you are being during this difficult time.”

Putting It All Together

Before you reflexively say, "Those soundbites won't work for me with my adult child," remember this: These soundbites are meant to support you. They are the words to say to keep putting the oxygen mask first on you before you immediately offer it to a struggling adult child who may inadvertently suck you dry. Remember: Being your struggling adult child's emotion coach, and not their rescuer from the SWAT team, takes a different mindset. This mindset is to become a source for healthy de-escalation and pave the way to problem-solving and growth, without the drama.

For more, click here.

How to help children become adults? | Psychology

It is not enough to raise a child, it is necessary to make him independent and able to live separately from his parents. As a rule, adolescents and without the prompting of adults develop a desire for independence and independence - if loving adults do not interfere, but help, guide them on the right path with practical advice, and not luring them into a warm, cozy family nest. Just do not confuse independence and responsibility. If a young person considers himself too independent to be accountable to his parents for his actions, while sitting on their necks, these are the parents' problems, because they allowed it.

As a rule, adolescents and without the prompting of adults develop a desire for independence and independence - if loving adults do not interfere, but help, guide them on the right path with practical advice, and not luring them into a warm, cozy family nest. Just do not confuse independence and responsibility. If a young person considers himself too independent to be accountable to his parents for his actions, while sitting on their necks, these are the parents' problems, because they allowed it.

In order for a grown child to become independent, it is necessary to create developing conditions for him, under which he will want to learn and do something new. If, for some reason, the desire for independence in an adult “child” is manifested only in the fact that parents do not interfere with him doing his own business, but continue to provide him “both a table and a house,” then this is no longer independence, but dependency. Indeed, why should he get a job, rush somewhere, do something, if it is warm, dry and comfortable in his parents' house? But the words “dry and comfortable” are words from ads about diapers. Agree that by adulthood, concern for dryness and comfort should move from parents-grandmothers-nannies to a grown child.

Indeed, why should he get a job, rush somewhere, do something, if it is warm, dry and comfortable in his parents' house? But the words “dry and comfortable” are words from ads about diapers. Agree that by adulthood, concern for dryness and comfort should move from parents-grandmothers-nannies to a grown child.

Then you will have to take measures that force the heir to make some efforts for his self-sufficiency and further independent existence. Here are just methods of shock therapy on the principle of "all at once" here can turn into a disaster. Not every person is able to instantly learn to swim if he is thrown into the water - some may choke, and someone may start to panic, and such a panic will occur every time they see "big water". To accustom the child to independence (including financial) should be gradual. The situation in the family nest should gradually cease to satisfy all the needs of the "baby", and he will have to take care of himself more and more - while the parents' insurance will never hurt.

1. How would you like your child to be in a few years?

Do not be too lazy to write down. Standard short answers like “rich and famous”, “successful and healthy” will have to be detailed. What exactly (and how much) do you consider wealth, in what environment should he be famous, what is included in the concept of “success”, what are the boundaries of health? Try to detail the type of his activity, place of residence. For example: “He will graduate from a construction institute and work as an architect in a large construction company, receive such and such a salary and live in his own apartment.”

2. How does the child see his future?

Be sure to ask him himself - it may turn out that he dreams, for example, of a career as a journalist, and that he is graduating from college (if he has not yet quit his studies secretly from you) so as not to quarrel with his parents. It happens. And it is not a fact that if you give him the opportunity to realize his abilities (if they really exist, and not invented), he will not become a famous journalist, although he could turn out to be an ordinary architect.

It happens. And it is not a fact that if you give him the opportunity to realize his abilities (if they really exist, and not invented), he will not become a famous journalist, although he could turn out to be an ordinary architect.

3. Compare and discuss the results

Your goals may be diametrically opposed. Therefore, in achieving them, you act like a Swan, Cancer and Pike. You may not know much about your adult child's life. For example, you think that your main duty is to give your son a good classical education, and he has been going to couples for two years somehow, preferring to spend all his free time at the computer, inventing new programs, firmly deciding to become a programmer and quietly hating a liberal arts university, in which you "by pull" helped him to enter.

4. Find a compromise

Find a compromise

Perhaps the "child" quite sincerely believes that he does not need higher education, and as soon as you let him go free, the comprehension of science will end for him. Try to negotiate. For example, you help him with finances as long as he gets an education, and in his spare time he can do journalism or computers to his heart's content. In the end, if he really finds his calling in another field of activity, then getting a second education in a specialty will be much faster, cheaper and easier.

5. Discuss the role of money in his future life

How much can he earn if he does what he likes (at least for a start), and what kind of life will he lead? How much will he receive if he still does not complete his education? Maybe it makes sense to look for a job now? How exactly is he going to dispose of his money, what will he spend it on?

6. Financial preparation

Financial preparation

Does an adult child know how much money is spent on his maintenance? What is (at least approximately) the amount of expenses for food, accommodation, entertainment? Could he earn for himself? Maybe your heir is already working and can give part of his earnings for utilities and food? Explain that your goal is not to save money on an adult child, but to teach him how to handle money and become independent. It will not be superfluous to have a family discussion of the budget, the definition of priorities, the distribution of expenses.

7. Budget

Budgeting is the only way to control finances. If it seems petty to count money to the nearest penny, try to at least divide the money into heaps (envelopes, bills) with a clear purpose: for food, for paying utility bills, for paying tuition, for transport, for entertainment. If you give an adult child a certain amount per month for his expenses, do not hesitate to ask where exactly the money is spent. Do not specify the details with the meticulousness of the investigator, if the column (written or imaginary) of "entertainment" contains an amount not exceeding 20%, it is not necessary to specify how exactly he spends them. Not all adults can boast of financial maturity and balance in matters of money - what can we expect from a child (even an adult) who is still dependent on his parents.

If you give an adult child a certain amount per month for his expenses, do not hesitate to ask where exactly the money is spent. Do not specify the details with the meticulousness of the investigator, if the column (written or imaginary) of "entertainment" contains an amount not exceeding 20%, it is not necessary to specify how exactly he spends them. Not all adults can boast of financial maturity and balance in matters of money - what can we expect from a child (even an adult) who is still dependent on his parents.

8. Beautiful far away

Teach your child to save some of their money for the future. Otherwise, no matter how much you give him or how much he earns, it will always be not enough. Explain the mechanism of consumer loans and the consequences of its use. If possible, show loan agreements - focus on interest and commissions that come with an almost free loan.

9. Give your child time to adapt to your new living conditions in general and his upbringing in particular

Give your child time to adapt to your new living conditions in general and his upbringing in particular

Remember, your main task is not to punish illiteracy and unwillingness to get off your parent's neck, but teach to live independently, that is, to earn money on your own for your life, plan your income and expenses, and take responsibility for your actions in particular and for your life in general.

10. Can't or don't want to?

If a “child” doesn’t understand something and can’t learn, there are most likely two reasons for this:

a) you don’t explain well and he can’t understand;

b) he feels that you will still let him live comfortably in your bosom and will fulfill all his whims - so why strain, everything will be fine anyway. He will not want to study, he will not see the need for it ..

Tags: independence, upbringing, parents, children, relationships

Free flight: how to behave with adult children

46,453

For parentsThe older generation

in front of his parents. How to "reformat" your attitude towards a child who has long ceased to be a child in the generally accepted sense of the word? Where are the boundaries of intervention? How to maintain relationships with older children? How to remove the grown offspring from your own neck? Let's try to figure it out.

How to "reformat" your attitude towards a child who has long ceased to be a child in the generally accepted sense of the word? Where are the boundaries of intervention? How to maintain relationships with older children? How to remove the grown offspring from your own neck? Let's try to figure it out.

Do I need to help financially?

Many parents continue to support their adult children financially until they get back on their feet. Their desire is understandable: today young people have to start their careers with low-paid internships, and financial assistance comes in handy. But often it leads to the opposite result - adult children never get the skill to cope with difficulties on their own.

“If you want to motivate a child to earn money, don't help him, let him look for opportunities,” family psychologist Anna Varga advises in her book Systemic Family Therapy. “Parents who want to tie a child encourage addiction, help with money.”

But what is a loving parent to do, who does not find a place for himself, worrying about his child? “Of course, we cannot forbid ourselves to worry about what children do, how they live, how our grandchildren are raised, how finances are distributed, we cannot,” notes psychologist Svetlana Kartinina. “But worrying is one thing, and taking responsibility for their actions and actions is another.” Remember how the child took the first steps, how he fell and filled the first bumps. Let him do the same now.

“But worrying is one thing, and taking responsibility for their actions and actions is another.” Remember how the child took the first steps, how he fell and filled the first bumps. Let him do the same now.

Personal life - is it better (not) to interfere?

Today, many young people are in no hurry to start families. Some meticulously choose the right partner, others put off this step, building a career or trying to sort themselves out. This situation inevitably causes concern for parents. “My daughter is 21 and she still has no love life. Moreover, she does not aspire to it, ”lamented 45-year-old Eleanor. And 54-year-old Svetlana complains that her daughter "has many admirers, but she finds some flaws in everyone and believes that there are no worthy ones, she is not going to get married."

“Anxiety is understandable, but interest in relationships should wake up on its own, and not because you want it,” comments Jungian analyst Larisa Kharlanova on such situations.

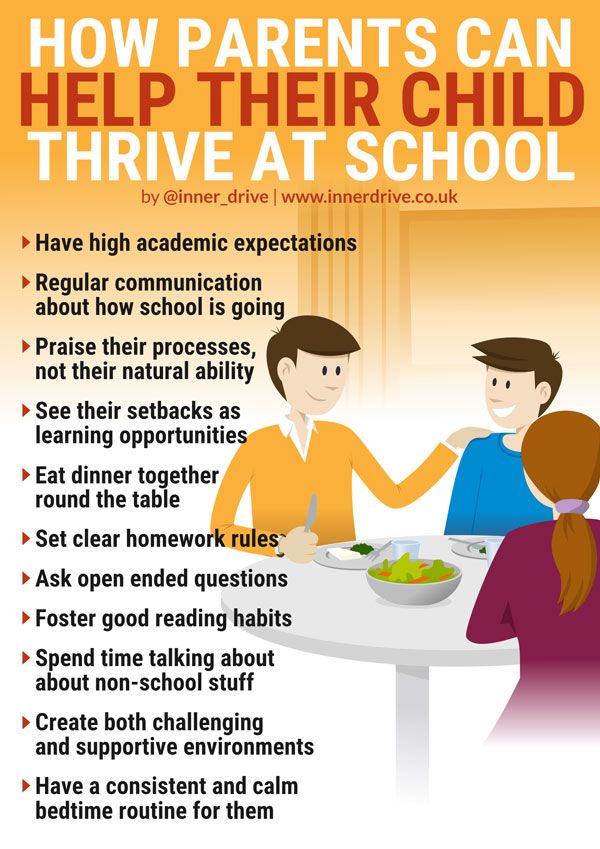

Some parents are used to controlling their children in everything. First, this manifests itself in checking homework and writing essays for the child, and then in trying to improve his personal life by choosing a suitable partner. It is important for a son or daughter in childhood to learn to take responsibility for their own actions, otherwise they will not be able to truly grow up.

Separation is rarely painless, more often it is accompanied by quarrels and misunderstandings. It happens that parents come to see a psychologist and begin to complain about aggression and rudeness on the part of adult children. “I congratulate them: finally, their boy or girl is growing up, being initiated into adulthood,” says psychotherapist Ilya Suslov.

When children sit on their necks

If some parents try to control and patronize adult children, others face the opposite problem: the child is in no hurry to grow up and takes their care for granted. He likes to live in his parents' house, where there is always food in the refrigerator, someone washes his clothes and pays the bills.

“Many young people perceive the family simply as a base, a launching pad, with little thought about their place in this unit of society and their share of responsibility for it, especially if they are really not used to being responsible for anything,” write Jill Hines and Alison Beiverstock in Your Adult Children. Parents complain about the irresponsibility of the child, the unwillingness not only to arrange their own lives, but also to do part of the housework. They feel at a dead end: as soon as they stop cleaning up after their grown son or daughter, the apartment will immediately sink into disarray.

Sometimes support means reminding a person that he is not a little capricious child at all, but an adult and independent person

Hines and Beiverstock recommend making a list of things that you do around the house and then showing it to an adult child. Perhaps the son or daughter will be surprised and say that they do not have to clean the apartment, but the authors insist: “If you want children to become more responsible, follow the only rule: stop doing everything for them and wait until they start doing it themselves. <...> If all family members begin to take responsibility for themselves, they finally become a group of equal adults living under the same roof.”

<...> If all family members begin to take responsibility for themselves, they finally become a group of equal adults living under the same roof.”

Most likely, someone will be surprised: isn't the first task of a loving parent to support the child, providing him with comfortable conditions in which he can develop and stand on his own feet? “Support is not only kind words and attention, sometimes support means reminding a person that he is not a small capricious child at all, but an adult and independent person,” explains psychologist Veronika Leonova. “Because that’s the kind of person who can get through the hard times, get through the hard times, and move on. And a capricious child, for whom parents do everything, is unlikely to cope with this task.

About the causes of parental fears and anxieties

The growing up of a child entails changes not only for himself, but also for the entire family system. A parent who is accustomed to taking care of, solving any problems of children, is out of work, feels helpless. It is especially difficult for a woman who primarily associates herself with the role of a mother. In her own crisis, she clings to every opportunity to help an adult child in order to feel useful and meaningful.

It is especially difficult for a woman who primarily associates herself with the role of a mother. In her own crisis, she clings to every opportunity to help an adult child in order to feel useful and meaningful.

“Secession is a two-way process,” emphasizes Inna Khamitova. When children grow up, parents also have to get used to the new situation. They may not be ready for parting because they are afraid of the emptiness that forms in life.

Watching how a little girl turns into an adult woman, a mother can experience conflicting feelings: joy and anxiety at the same time. She is afraid that her daughter will make mistakes or, conversely, repeat her bad experience. In addition, the youth of children inevitably reminds her of her own age.

“If there is no distance between them, the mother seems to “appropriate” her daughter's life, wants to live for her and does not allow her to make decisions,” explains Jungian analyst Anna Kazakova. - They form a pair, excluding the presence of a third. If a daughter has a partner, the mother does everything to expel him in any way. In fact, the daughter gets a ban on the manifestation of her own feelings and sexuality.

If a daughter has a partner, the mother does everything to expel him in any way. In fact, the daughter gets a ban on the manifestation of her own feelings and sexuality.

So how do you approach them?

Parents and children are always people of different generations. They grew up and matured at different times and in different conditions. Contradictions between them are inevitable, but at the same time this does not mean that their relationship cannot be built on mutual respect and love. While the child is small, it is easier for parents to get what they want from him: he is still controllable, reacts to prohibitions. But such tactics fail in adolescence, and it is almost impossible to command a completely adult person.

There will always be boundaries between parents and children that exclude some topics from their communication "in old age," explains Natalya Manukhina in the book "Parents and adult children."Treating your son or daughter as an equal participant in the dialogue helps to establish a conversation with children of any age: no matter how old your child is three or thirty.