How to help a child with executive functioning problems

Your Child's 7 Executive Functions — and How to Boost Them

Mom helping her ADHD daughter with homework1 of 11

Understanding Executive Dysfunction

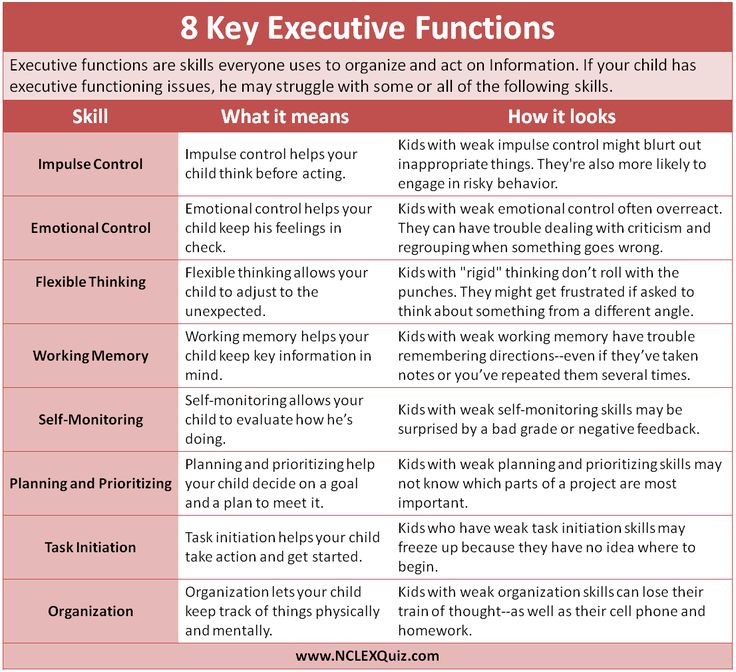

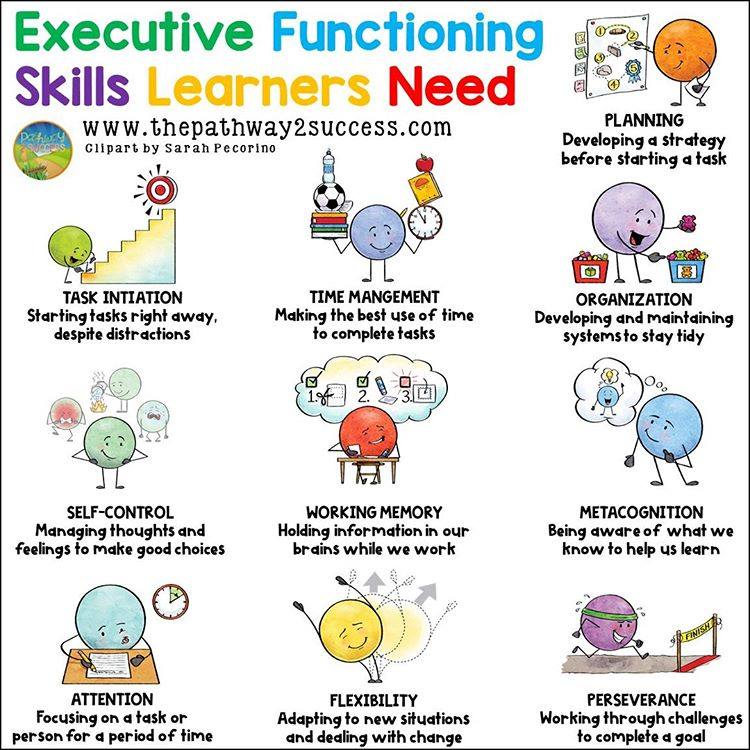

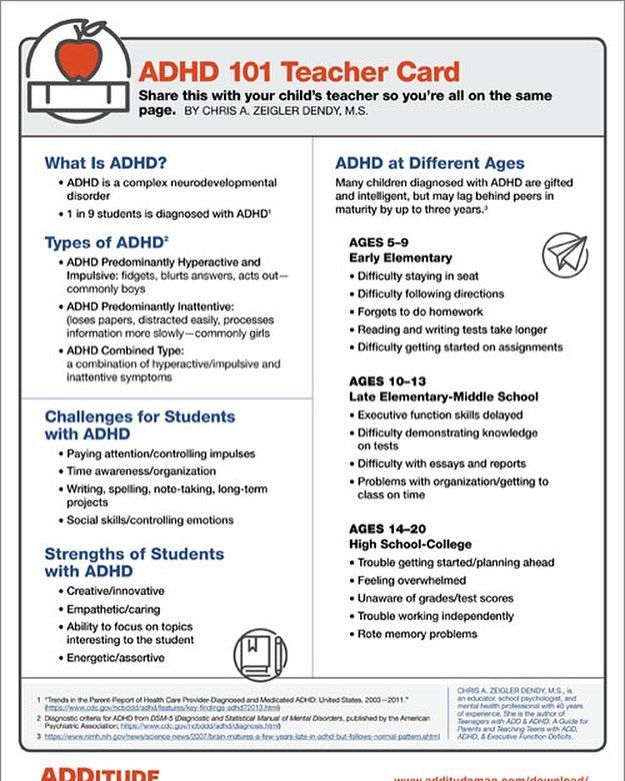

Children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD) tend to struggle with these 7 core executive dyfunctions:

- Self-awareness

- Inhibition

- Non-verbal working memory

- Verbal working memory

- Emotional self-regulation

- Self-motivation

- Planning and problem solving

Here's how you can help your child build up these muscles, gaining more control over their ADHD symptoms and taking strides toward independence along the way.

A father sits in the grass under a tree and talks with his son about executive function2 of 11

1. Enforce Accountability

A lot of parents wonder how much accountability is appropriate. If ADHD is a disability outside of my child’s control, should she be held accountable for her actions?

My answer is an unequivocal yes. The problem with ADHD is not with failure to understand consequences; it’s with timing. With the steps that follow, you can help your child bolster her executive functions — but the first step is to not excuse her from accountability. If anything, make her more accountable — show her you have faith in her abilities by expecting her to do what is needed.

3 of 11

2. Write It Down

Compensate for working memory deficits by making information visible, using notes cards, signs, sticky notes, lists, journals — anything at all! Once your child can see the information right in front of him, it’ll be easier to jog his executive functions and help him build his working memory.

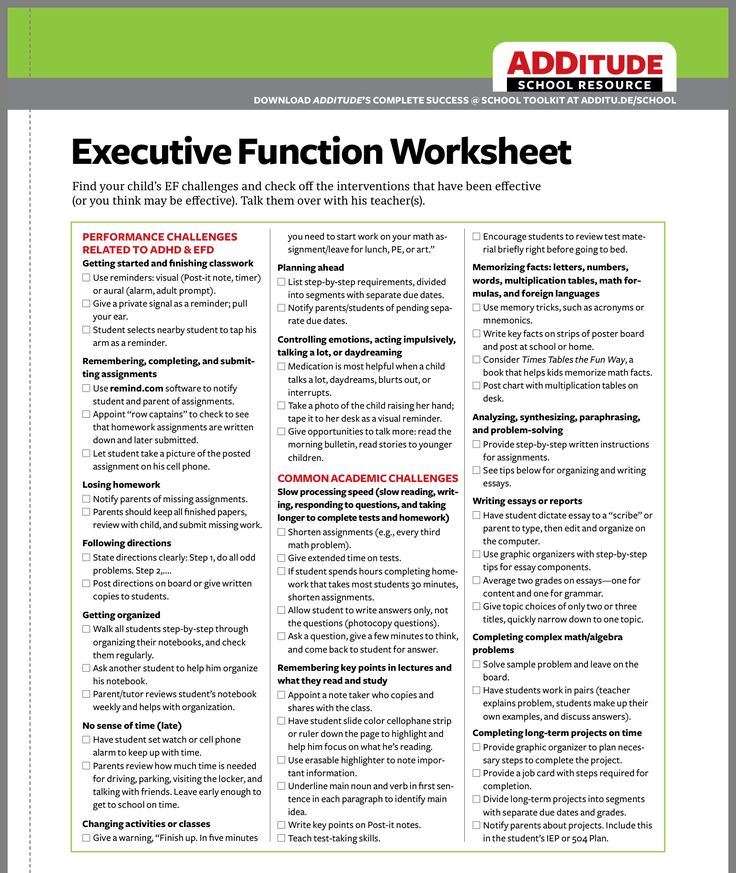

[Download This Free Checklist: Common Executive Function Challenges — and Solutions]

Three pocket watches in sand. People with impaired executive function need them to keep track of time.

4 of 11

3. Make Time External

Make time a physical, measurable thing by using clocks, timers, counters, or apps — there are tons of options! Helping your child see how much time has passed, how much is left, and how quickly it’s passing is a great way to beat that classic ADHD struggle, “time blindness.”

A doctor gives a girl a lollipop after teaching her about executive function.5 of 11

4. Offer Rewards

Use rewards to make motivation external. Someone who struggles with executive functions will have trouble motivating herself to complete tasks that don’t have immediate rewards. In these cases, it’s best to create artificial forms of motivation, like token systems or daily report cards. Reinforcing long- term goals with short-term rewards strengthens a child’s sense of self-motivation.

A child with ADHD holds 1,2,3 stacked blocks – close up6 of 11

5.

Make Learning Hands On

Make Learning Hands OnPut the problem in their hands! Making problems as physical as possible — like using jelly beans or colored blocks to teach simple adding and subtracting, or utilizing word magnets to work on sentence structure — helps children reconcile their verbal and non-verbal working memories, and build their executive functions in the process.

A mom reads a book about executive function to her daughter laying in her lap on the couch7 of 11

6. Stop to Refuel

Self-regulation and executive functions come in limited quantities. They can be depleted very quickly when your child works too hard over too short a time (like while taking a test). Give your child a chance to refuel by encouraging frequent breaks during tasks that stress the executive system. Breaks work best if they’re 3 to 10 minutes long, and can help your child get the fuel they need to tackle an assignment without getting distracted and losing track.

[Take This Test: Could Your Child Have an Executive Function Disorder?]

A baseball coach and his players with ADHD cheer after winning a game8 of 11

7.

Practice Pep Talks

Practice Pep TalksYou know that locker room pep talk before a big game? Your child needs one every day — sometimes more often. Teach your child to pump herself up by practicing saying “You can do this!” Positive self-statements push kids to try harder and put them one step closer to accomplishing their goals. Visualizing success and talking themselves through the steps needed to achieve it is another great way to replenish the system and boost planning skills.

A boy with ADHD holds a soccer ball and leans against a tree in a park9 of 11

8. Get Physical

Physical exercise has tons of well-known benefits — including giving a boost to your child’s executive functioning! Routine physical exercise throughout the week can help refuel the tank (even make the tank bigger!) and help him cope better with his ADHD symptoms. Exercise can be found anywhere — try an organized sport, a bi-weekly park playdate, or a spur-of-the-moment run around the backyard!

A boy drinks juice with his cereal to boost executive function with sugar10 of 11

9.

Sip on Sugar (Yes, Really)

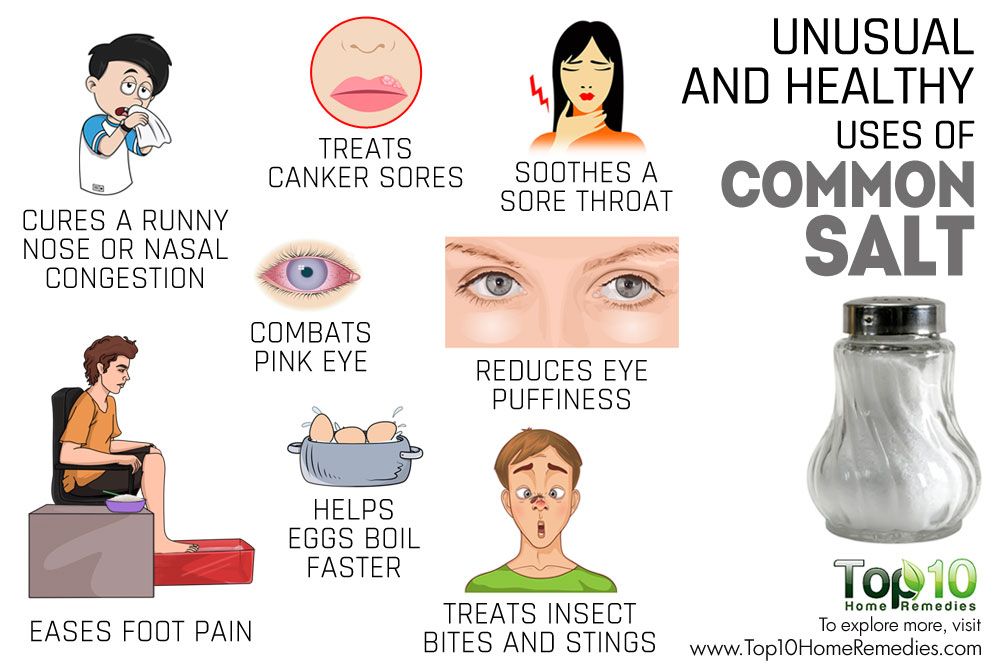

Sip on Sugar (Yes, Really)Sugar has sometimes been known to exacerbate ADHD symptoms, but when your child is doing a lot of executive functioning (like taking an exam or finishing a big project), it may be a good idea to have her sip on some sugar-containing fluids, like lemonade or a sports drink. The glucose in these drinks fuels the frontal lobe, where the executive functions come from. The operative word here is “sip” — just a little should be able to keep your child’s blood glucose up enough to get the job done.

A boy with ADHD hugs his father after a hard day11 of 11

10. Show Compassion

This is a big one, folks. In most cases, individuals with ADHD are just as smart as their peers, but their executive function problems keep them from showing what they know. The key to treatment ischanging their environment to help them do that. So it’s important that the people in their lives — especially parents — show compassion and willingness to help them learn. When your child messes up, don’t go straight to yelling. Try to understand what went wrong — and how you can help him learn from his mistake.

When your child messes up, don’t go straight to yelling. Try to understand what went wrong — and how you can help him learn from his mistake.

[Read This Next: Treatments for Weak Executive Functions]

Help for Executive Functions | Child Mind Institute

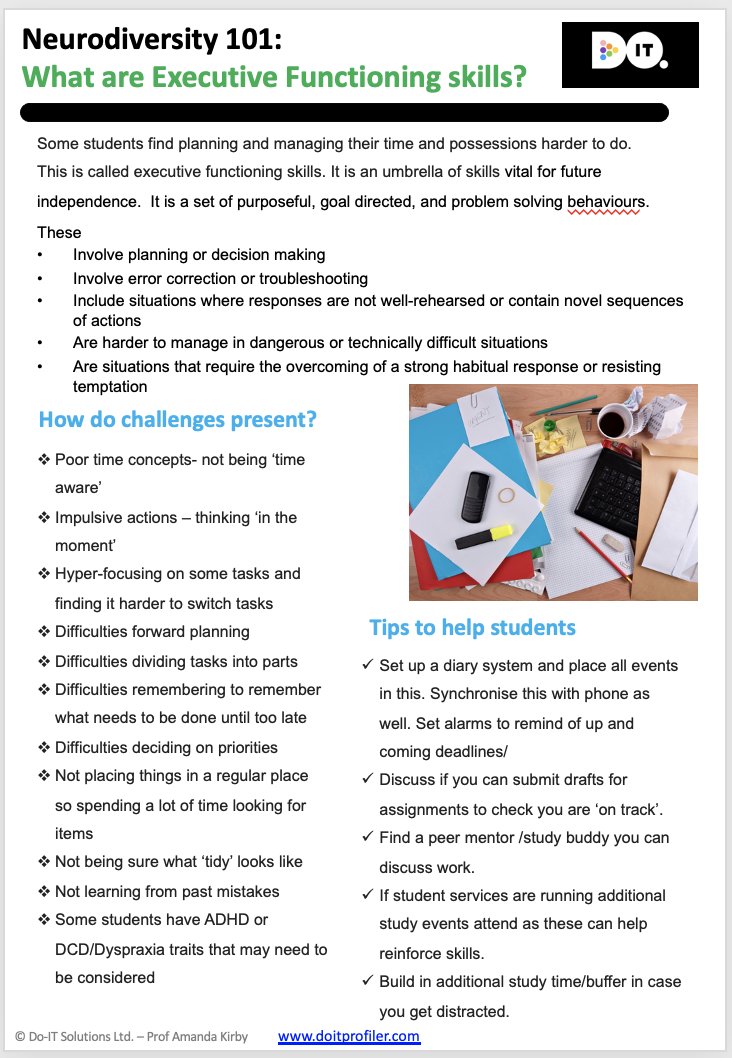

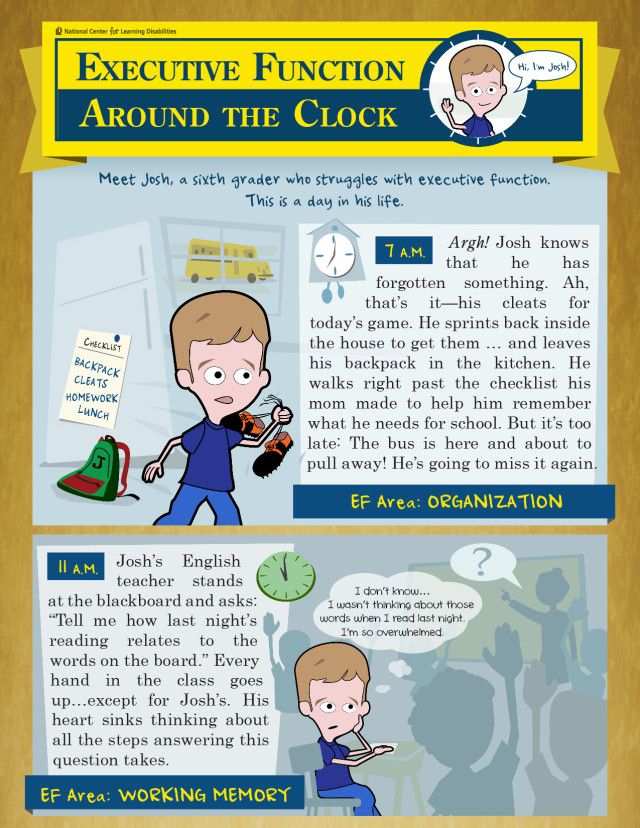

The first time you hear that your 7-year-old son is weak in “executive functions” it sounds like a joke. No kidding—that’s why he’s a first grader, not a CEO. But executive functions are the essential self-regulating skills that we all use every day to accomplish just about everything. They help us plan, organize, make decisions, shift between situations or thoughts, control our emotions and impulsivity, and learn from past mistakes. Kids rely on their executive functions for everything from taking a shower to packing a backpack and picking priorities.

Children who have poor executive functioning, including many with ADHD, are more disorganized than other kids. They might take an extraordinarily long time to get dressed or become overwhelmed while doing simple chores around the house. Schoolwork can become a nightmare because they regularly lose papers or start weeklong assignments the night before they are due.

Schoolwork can become a nightmare because they regularly lose papers or start weeklong assignments the night before they are due.

Learning disorder specialists have devised ways to bolster the organizational skills that don’t come naturally to a child with poor executive functioning. They teach a mix of specific strategies and alternative learning styles that complement or enhance a child’s particular abilities. Here are some of the tools they teach kids—and parents—to help them tackle school work as well as other responsibilities that take organization and follow-through.

Checklists

The steps necessary for completing a task often aren’t obvious to kids with executive dysfunction, and defining them clearly ahead of time makes a task less daunting and more achievable. Following a checklist of steps also minimizes the mental and emotional strain many kids with executive dysfunction experience while trying to make decisions. Ruth Lee, an educational therapist, explains, “Often these kids will get so wrapped up in the decision-making process that they never even start the task. Or, if they do begin, they’re constantly starting and restarting because they’ve thought of a better way to do it. In the end they’re exhausted when the time comes to actually follow though.” With a checklist, kids can focus their mental energy on the task at hand.

Or, if they do begin, they’re constantly starting and restarting because they’ve thought of a better way to do it. In the end they’re exhausted when the time comes to actually follow though.” With a checklist, kids can focus their mental energy on the task at hand.

You can make a checklist for nearly anything, Lee notes, including how to get out of the house on time each morning—often a daily struggle for kids with executive dysfunction. Some parents say posting a checklist of the morning routine can be a sanity saver: make your bed, brush your teeth, get dressed, have breakfast, grab your lunch, get your backpack. Lee also recommends completing as many of the morning tasks as possible the night before. Lunches can be made ahead of time, clothes can be laid out, and backpacks can be packed and waiting by the door. It takes a little extra planning, she adds, but doing the work ahead of time can prevents a lot of drama the next day.

Set time limits

When making a checklist, many educational therapists also recommend assigning a time limit for each step, particularly if it is a bigger, longer-term project. Matthew Cruger, PhD, Director of the Child Mind Institute Learning and Development Center, likes to practice breaking down different kinds of homework assignments with kids to get them used to the steps required—and how long they might take. He describes recently working with a fifth grader who could think of only two steps required to complete a book report—writing the report and then turning it in. The time involved in reading the book slipped his mind.

Matthew Cruger, PhD, Director of the Child Mind Institute Learning and Development Center, likes to practice breaking down different kinds of homework assignments with kids to get them used to the steps required—and how long they might take. He describes recently working with a fifth grader who could think of only two steps required to complete a book report—writing the report and then turning it in. The time involved in reading the book slipped his mind.

Use that planner

Educational specialists also highlight the cardinal importance of using a planner. Most schools require students to use a planner these days, but they often don’t teach children how to use them, and it won’t be obvious to a child who is overwhelmed by—or uninterested in—organization and planning. This is unfortunate because kids who struggle with executive functioning issues have poor working memory, which means it is hard for them to remember things like homework assignments. And working memory issues tend to snowball. Dr. Cruger explains, “Kids don’t remember that they won’t remember their homework if they don’t write it down. It doesn’t matter how many times they forget. Once a frustrated father told me, ‘It’s like he has this delusion that he’ll remember it!’” As a backup to planners, many schools are also using software platforms like eChalk to create webpages teachers use to post homework assignments and handouts—giving kids with executive dysfunction one less thing to worry about.

Dr. Cruger explains, “Kids don’t remember that they won’t remember their homework if they don’t write it down. It doesn’t matter how many times they forget. Once a frustrated father told me, ‘It’s like he has this delusion that he’ll remember it!’” As a backup to planners, many schools are also using software platforms like eChalk to create webpages teachers use to post homework assignments and handouts—giving kids with executive dysfunction one less thing to worry about.

Spell out the rationale

While a child is learning new skills, it is essential that he understand the rationale behind them, or things like planning might feel like a waste of time or needless energy drain. Kids with poor organizational skills often feel pressured by their time commitments and responsibilities, and can be very averse to delay. “It’s almost like they’re making neuroeconomical decisions,” Dr. Cruger says. “They’re constantly weighing things to see if it’s worth their effort, and planning can feel like a waste of time if you don’t understand the rationale behind it. ” Older kids are particularly resistant because they’re more stuck in their ways. “They’ll say, ‘This is what works for me,’ even if their method really isn’t working,” says Dr. Cruger. Explaining the rationale behind a particular strategy makes a child much more likely to commit to doing it.

” Older kids are particularly resistant because they’re more stuck in their ways. “They’ll say, ‘This is what works for me,’ even if their method really isn’t working,” says Dr. Cruger. Explaining the rationale behind a particular strategy makes a child much more likely to commit to doing it.

Explore different ways of learning

Educational specialists like Mara Koffman, MA, who founded Braintrust, a tutoring service for kids with learning issues, advocate using a variety of strategies to help kids understand—and remember—important concepts. Visual learners, for example, benefit from using graphic organizers as a reference. Students learning how to write a paragraph might follow the hamburger paragraph model, a diagramed drawing of a hamburger in which each sandwich component matches a part of a paragraph—the top bun is the thesis, the three supporting sentences are the lettuce, tomato, and patty, and the bottom bun is the conclusion sentence. Some versions of the hamburger paragraph act as a visual aid while others double as forms that a child can fill in.

Other kids remember things better if there is a motion supporting it, like counting on their fingers, which is good for visual and tactile learners. Younger children benefit from self-talking to reduce anxiety and Social Stories, which are narratives about a child successfully performing a certain task or learning a particular skill. Social Stories are told from a child’s first-person perspective and are similar to self-talk, but they can also double as a checklist because they break tasks into clear steps and can be referred to later.

As kids get older and are expected to memorize a lot of dry factual information, Koffman recommends mnemonic devices as a way to structure information in a more memorable way. But with all of the different learning strategies out there, Dr. Cruger stresses the importance of not overwhelming kids. Ideally the educational specialist should be working with your child on one new skill at a time, and spending at least two weeks practicing before evaluating how effective or ineffective it is and moving on to anything new.

This is particularly important for older kids, who typically struggle more to get started with their homework. Educational specialists recommend starting homework at the same time every day. Expect some resistance from older kids, who often prefer to wait until they feel like doing their work. Dr. Cruger strongly advises against waiting to start homework. “Realistically, the desire to start homework probably isn’t going to come. A kid who is waiting for inspiration to strike will still be forced to start his homework eventually, but it will probably be at 11 o’clock. That’s clearly a bad work model.” Ideally, kids should come home, unpack their bag, have a snack, and then get started. Homework is best done in a quiet, well-lit space fully stocked with paper and pencils because a search for supplies can quickly derail homework time. Any space with minimal distractions is good. Some families find doing homework on the kitchen table works best for their child, particularly if a parent is nearby to supervise and answer questions.

Use rewards

For younger kids, Koffman recommends putting a reward system in place. “Younger kids need external motivators to highlight the value of these new strategies. Something like a star chart, where kids see the connection between practicing their skills and working towards a reward, works very well.” Besides, Koffman notes, “It’s also a good way to communicate to kids that their parents and their teacher also value this skill.” If you’re using a reward chart, hanging it in the designated homework area can be a good incentive. For older kids who aren’t as motivated by things like rewards, parents should still be encouraging. Koffman recommends parents checking in with older kids. “Ask how things are going or offer help. Tell them you appreciate all the hard work they’re doing. School is really hard for a lot of kids—it shouldn’t be a given that learning these things is easy.”

Developing new strategies for learning isn’t easy either. Initially, it can put kids who are already self-conscious even further outside their comfort zone, but it’s worth the effort. We use our organizational skills every day in a million ways, and they are essential to our success in school and later as adults. Getting organized even gives us more time to play videogames.

We use our organizational skills every day in a million ways, and they are essential to our success in school and later as adults. Getting organized even gives us more time to play videogames.

5 reading problems due to underdeveloped executive functions

-

Learning to read requires the development of executive functions

-

Children with executive function problems may have difficulty reading

-

They may confuse similar letters and have difficulty reading aloud.

Executive functions play a large role in various aspects of learning to read. They are the key to learning the alphabet and understanding the meaning of words. Therefore, when children have poorly developed executive functions, certain reading difficulties may arise. Listed below are five ways that executive function problems can affect reading.

1. Executive function and letter recognition

Children with executive function problems may confuse letters when learning the alphabet. This is because when they learn something new, it is difficult for them to leave it and switch to something else.

This is because when they learn something new, it is difficult for them to leave it and switch to something else.

For example, let's take the letters "G" and "T". If a child first learns the letter "G", he may not immediately understand that "T" looks like it, but "T" still has a small stick. Subconsciously, he will stubbornly see "G" in her. The child needs to maintain attention long enough to realize that the extra wand turns "G" into "T".

2. Executive function and pronunciation of words

Beginning readers spell words they are unfamiliar with. This can be difficult for children with executive function problems.

Due to problems with working memory, which is a key executive function, as they slowly read the end of a word, they forget the beginning. It can also affect the full understanding of the text. The child may be so focused on parsing each word that he loses the meaning of the text he is reading.

3. Executive function and homonyms

Words that sound and are spelled the same but have different meanings can be a hindrance even for advanced readers. The child needs to apply flexible thinking, another executive function, to understand how a word can be used in different meanings.

The child needs to apply flexible thinking, another executive function, to understand how a word can be used in different meanings.

For example, if a child comes across the phrase "put a spoke in the wheel", he will understand it literally. But, thinking about the context, he will understand that the phrase does not make sense, which means that it means something else.

Such thinking requires developed executive functions. It is very difficult for children with executive function problems to leave the literal or commonly used meaning of a word and think of an alternative. The child may not guess to use the context in the form of other words or pictures to the text. Because of this, he will not understand what he read, or it will take him more time to understand the text than other children.

4. Executive function and passive voice

When children are learning to read, most sentences are in the active voice. “Sonya pushed Kolya” is an example of an active voice. Over time, children move on to complex sentences. "Kolya pushed Sonya" - the meaning of the sentence has not changed, but children with executive functions problems can understand this as Kolya pushed Sonya.

Over time, children move on to complex sentences. "Kolya pushed Sonya" - the meaning of the sentence has not changed, but children with executive functions problems can understand this as Kolya pushed Sonya.

The child remembers that the subject comes first, then the predicate, and at the end the object. Therefore, having seen that the first word in the sentence is "Kolya", the child continues to read, mentally jumping over the next two words, not noticing how the endings have changed, and along with them the meaning. Again, this is because the child remembered one rule and was unable to switch to a new one. Thus, the child does not understand the meaning of the sentence.

5. Executive function and attention

It takes effort to learn something new, and reading is no exception. The child should sit still, concentrate and not be distracted. Children with executive function problems often have difficulty concentrating. Because of this, it is more difficult for them to understand the meaning of the sentence, since in the middle they can be distracted and lost.

How can you help?

Reading requires many skills. Children with executive function problems may need extra practice to learn the basics of reading.

If your child is having difficulty reading, talk to their teacher and ask for help. You can ask your child to be tested and transferred to special education. By testing the child, you can better understand the reason why he has difficulty with reading and executive functions, perhaps the child has HAI (auditory perception disorder) or dyslexia.

Learn how to develop executive function in children of all ages.

Give your child a training session to develop executive functions and reading skills using the innovative Fast ForWord methodology.

This technique gets to the root of problems associated with impaired development of executive and other cognitive functions and thus quickly and permanently eliminates will help your child become a successful reader and student.

Practice with a special program - an online reading simulator Reading Assistant.

Pins

-

Children who are weak in these executive functions have difficulty reading and understanding what they read;

-

With extra help and support, these children can learn to read quickly.

Source

Child Development - Child Development

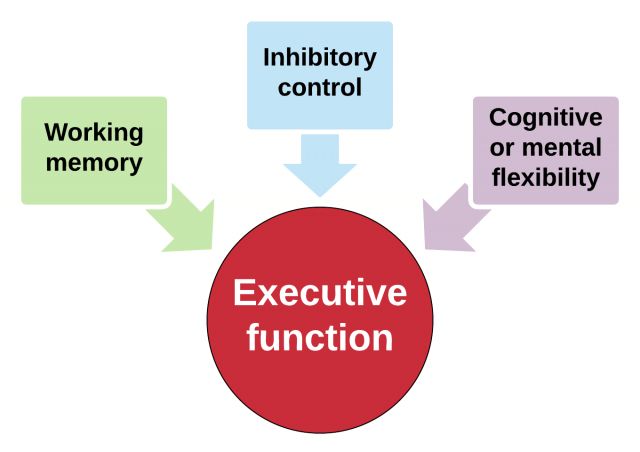

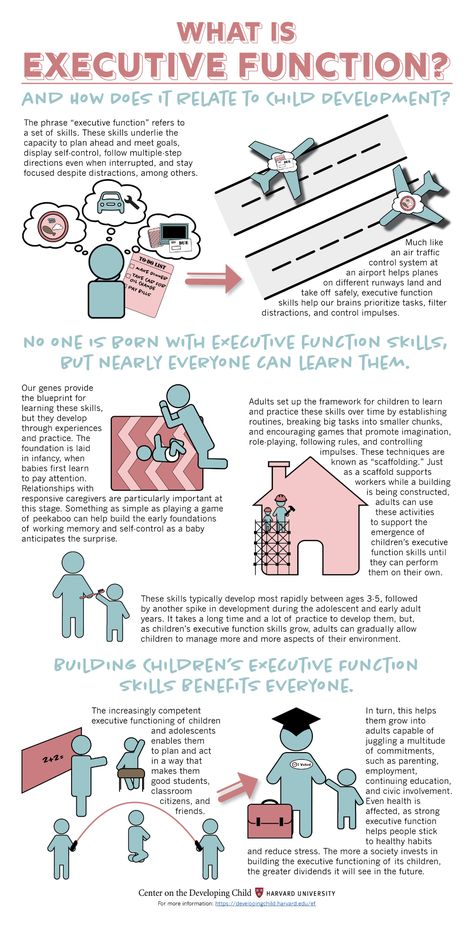

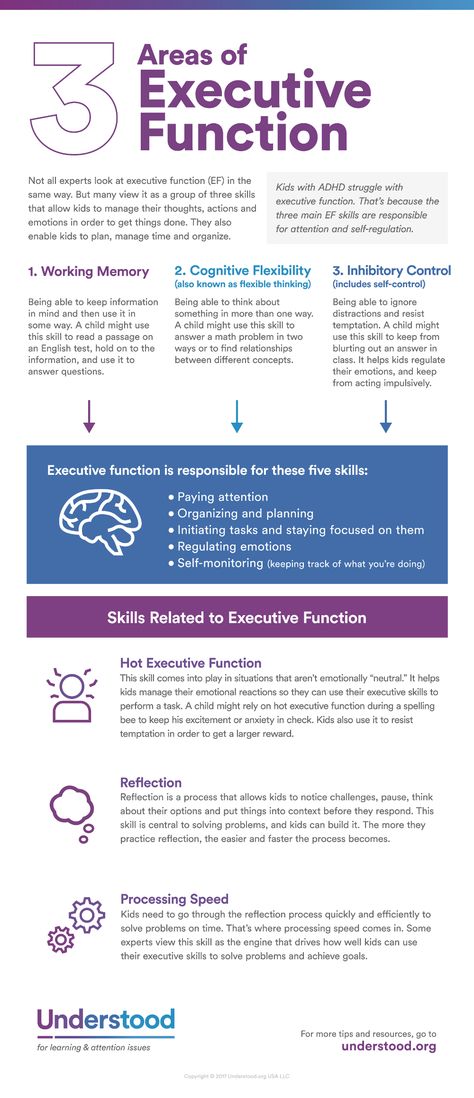

Executive functions are the cognitive skills we need to control and regulate our thoughts, emotions, and actions in times of conflict or distraction. Psychologists sometimes distinguish between "cold" executive functions, which are strictly cognitive skills (such as mental numeracy), and "hot" executive functions that help regulate emotions (such as the ability to manage anger).

There are three types of executive functions:

1. Self-control - the ability to resist temptation and do the right thing instead. Self-control helps children focus, act less impulsively, and stay focused while doing work.

Self-control helps children focus, act less impulsively, and stay focused while doing work.

2. Working memory - the ability to remember information, guess where it might be used, connect ideas, and prioritize.

3. Cognitive flexibility - the ability to think creatively and change one's behavior in accordance with changing circumstances. Cognitive flexibility allows us to use our imagination and creativity to solve problems.

How important is this?

Executive functions are very important for a child's development. This is evidenced by the fact that by the extent to which the child's executive functions are developed at an early age, it can be assumed with a high degree of certainty how high his school performance will be, how much he will be able to adapt in society, how much he will adhere to a healthy lifestyle and etc.

It is therefore essential for parents to find ways to support the development of executive functions in the early years of a child's life.

What is known already and ?

It takes time for a child to fully develop executive functions. This is partly due to the slow maturation of the prefrontal cortex. Development of executive functions becomes noticeable when children remind themselves of important goals (for example, when they refuse to watch TV in order to do their homework).

Also, development of executive functions occurs when children learn to analyze the environment in order to decide how to act in a given situation (for example, they understand that they need to learn lessons in order to pass an exam, and therefore refuse to watch TV). Lack of executive development may explain, for example, why young children seem stubborn and refuse to follow their parents' logical directions (eg, refuse to wear a hat in winter). Often, executive functions are poorly developed in children raised in poor families.

Children are very sensitive to early emotional experiences that may interfere with the development of executive functions or, conversely, contribute to it. For example, stress can be so detrimental to the development of a child's executive functions that their behavior may be similar to that of a child with ADHD (which is why children with impaired executive functions are often misdiagnosed as ADHD).

For example, stress can be so detrimental to the development of a child's executive functions that their behavior may be similar to that of a child with ADHD (which is why children with impaired executive functions are often misdiagnosed as ADHD).

On the other hand, positive emotional experiences (for example, good relationships with parents at an early age) can protect the child from the negative influence of stress factors (for example, difficult financial conditions of the family). Therefore, executive functions in such children develop normally. Children of responsive parents who use a gentle approach to parenting rather than strict discipline also tend to develop their executive functions better.

Well-developed executive functions lead to high academic achievement, well-developed social and emotional skills. In the early grades, executive functions have a stronger influence on a child's academic performance than intelligence and ability to read or count. Psychologists suggest that this is due to the fact that executive functions help the child navigate in an ever-changing environment. Therefore, their development is especially important for those children who grow up in disadvantaged conditions.

Therefore, their development is especially important for those children who grow up in disadvantaged conditions.

Separate executive functions are connected with the fact that the child understands the thoughts and actions of other people. For example, a child understands that other people may have ideas about the world that are different from their own. This is a necessary skill for successful social interaction.

The benefits of well-developed executive functions are clear. At the same time, poor development of executive functions is characteristic of a number of disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, behavioral and learning disorders, autism, depression, etc. Early problems with the development of executive functions can persist throughout childhood and even adolescence.

What can do ?

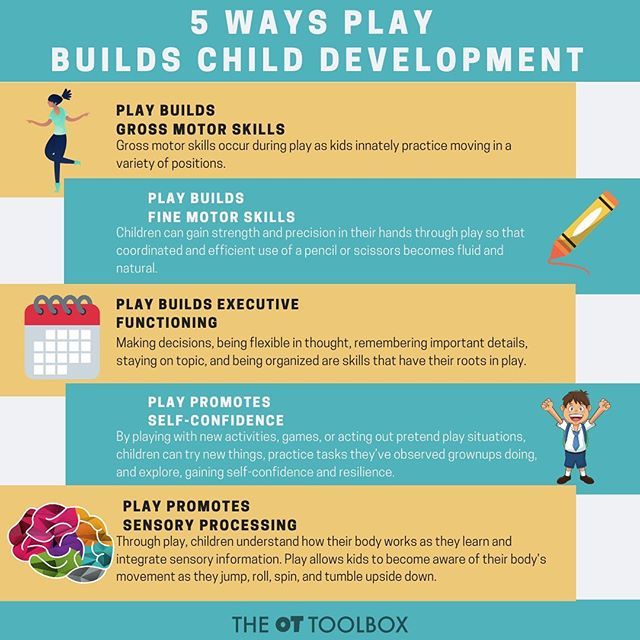

Working with a child psychologist can help preschoolers develop their executive functions. Through this, they can improve academic performance, develop social and emotional skills, and create new neural connections. Early intervention can also reduce the difficulties associated with disorders such as ADHD and conduct disorders. Such classes give good results for children aged 4-5 years. In the course of such classes, the child learns the skills of self-regulation, most often in a playful way.

Through this, they can improve academic performance, develop social and emotional skills, and create new neural connections. Early intervention can also reduce the difficulties associated with disorders such as ADHD and conduct disorders. Such classes give good results for children aged 4-5 years. In the course of such classes, the child learns the skills of self-regulation, most often in a playful way.

There are also a number of activities that help develop the child's executive functions. Such activities include music, yoga, meditation, martial arts, etc.

It is also worth paying attention to the atmosphere in which learning takes place in the lower grades. Children should be more active during the lesson, so spend more time in small groups and less time in large groups. Children with well-developed executive functions require less intervention from teachers. It is also important to eliminate all stress factors in the learning process. Younger children should also be taught in a playful way.