How to help a child with autism transition

Transition Time: Helping Individuals on the Autism Spectrum Move Successfully from One Activity to Another: Articles: Indiana Resource Center for Autism: Indiana University Bloomington

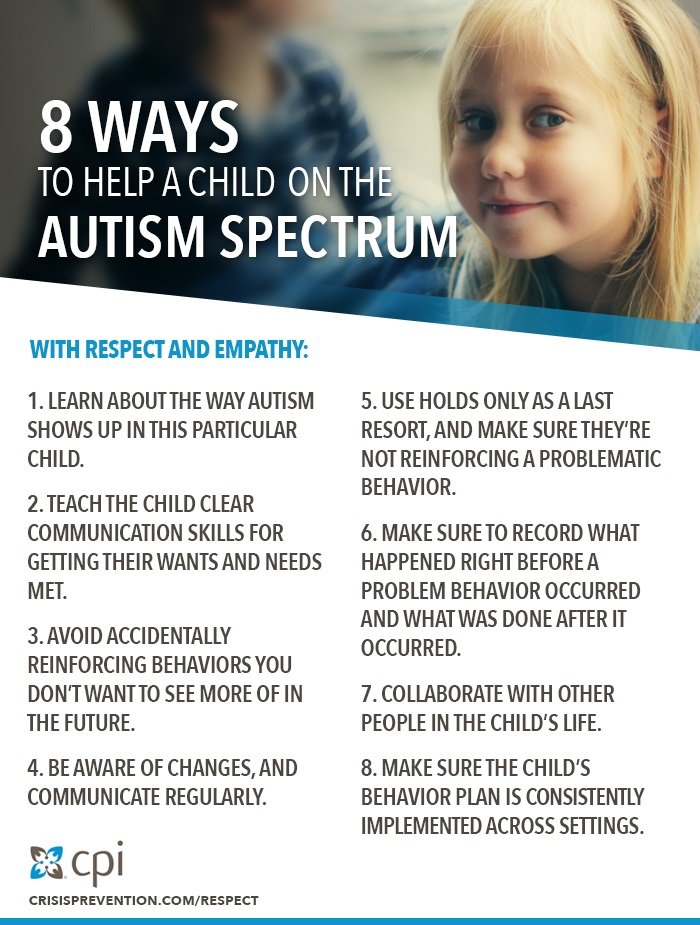

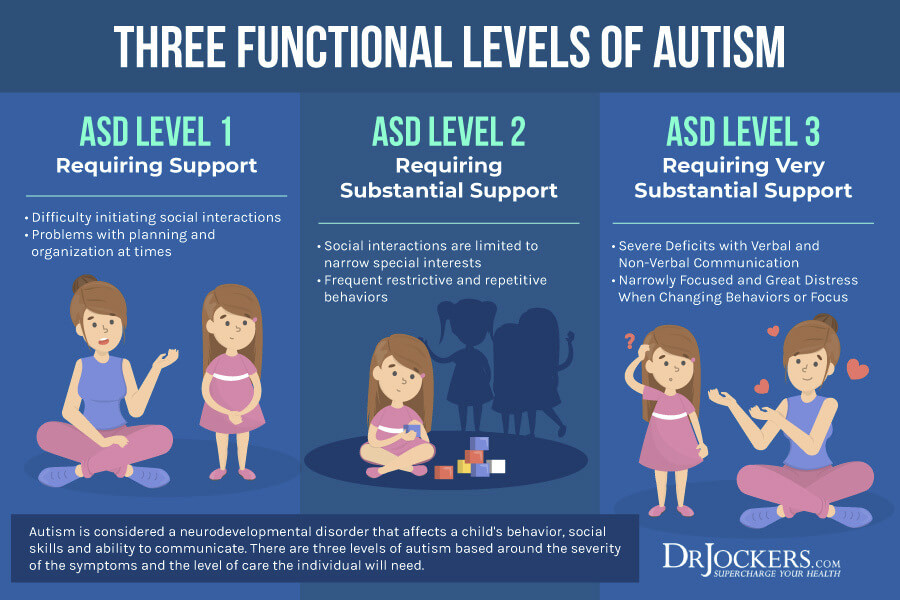

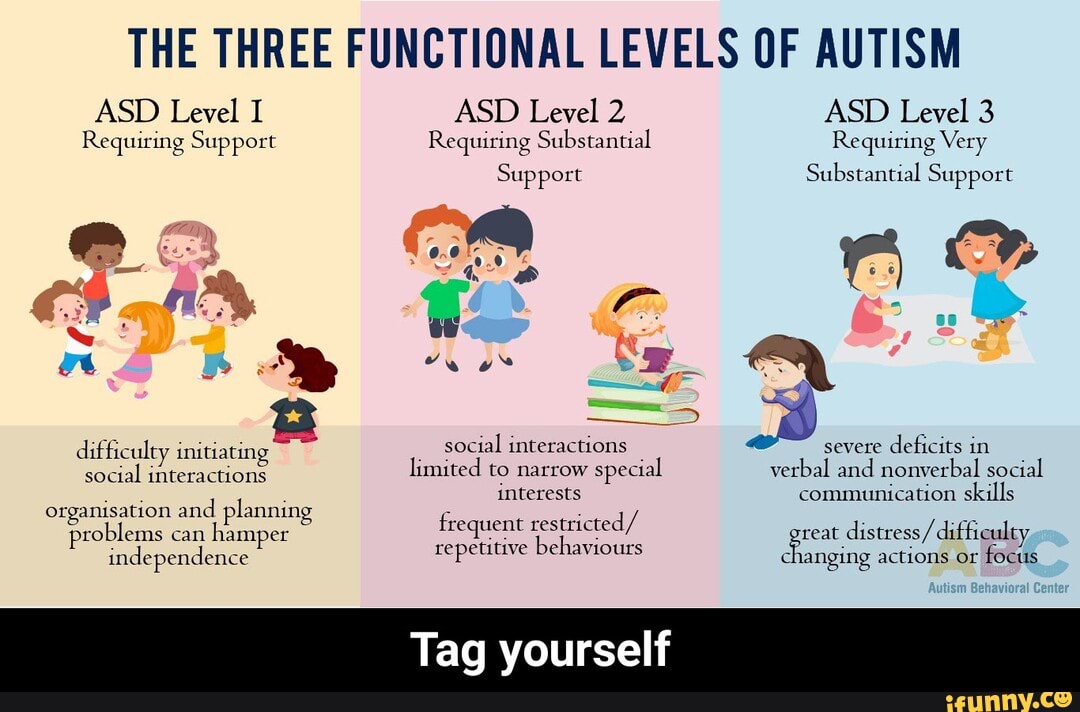

All individuals must change from one activity to another and from one setting to another throughout the day. Whether at home, school, or in the workplace, transitions naturally occur frequently and require individuals to stop an activity, move from one location to another, and begin something new. Individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may have greater difficulty in shifting attention from one task to another or in changes of routine. This may be due to a greater need for predictability (Flannery & Horner,1994), challenges in understanding what activity will be coming next (Mesibov, Shea, & Schopler, 2005), or difficulty when a pattern of behavior is disrupted. A number of supports to assist individuals with ASD during transitions have been designed both to prepare individuals before the transition will occur and to support the individual during the transition. When transition strategies are used, individuals with ASD:

- Reduce the amount of transition time;

- Increase appropriate behavior during transitions;

- Rely less on adult prompting; and

- Participate more successfully in school and community outings.

What are transition strategies?

Transition strategies are techniques used to support individuals with ASD during changes in or disruptions to activities, settings, or routines. The techniques can be used before a transition occurs, during a transition, and/or after a transition, and can be presented verbally, auditorily, or visually. The strategies attempt to increase predictability for individuals on the autism spectrum and to create positive routines around transitions. They are utilized across settings to support individuals with ASD.

Why do we use transition strategies?

Transitions are a large part of any school or work day, as we move to different activities or locations. Studies have indicated that up to 25% of a school day may be spent engaged in transition activities, such as moving from classroom to classroom, coming in from the playground, going to the cafeteria, putting personal items in designated locations like lockers or cubbies, and gathering needed materials to start working (Sainato, Strain, Lefebvre, & Rapp, 1987). Similar requirements for transitions are found in the employment and home setting as well, as individuals move from one task to another, attend functions, and join others for meals and activities.

Studies have indicated that up to 25% of a school day may be spent engaged in transition activities, such as moving from classroom to classroom, coming in from the playground, going to the cafeteria, putting personal items in designated locations like lockers or cubbies, and gathering needed materials to start working (Sainato, Strain, Lefebvre, & Rapp, 1987). Similar requirements for transitions are found in the employment and home setting as well, as individuals move from one task to another, attend functions, and join others for meals and activities.

Some individuals with ASD may have difficulties associated with changes in routine or changes in environments, and may have a need for “sameness” and predictability (Mesibov et al., 2005). These difficulties may eventually hamper one’s independence and limit an individual’s ability to succeed in community settings. A variety of factors related to ASD may contribute to these difficulties during transitions.

These may include problems in understanding the verbal directives or explanations that a teacher, parent, or employer are providing. When a teacher announces that an activity is finished and provides multi-step directions related to upcoming activities, students with ASD may not comprehend all of the verbal information. Difficulty sequencing information and recognizing relationships between steps of an activity can impact one’s ability to transition as well. Individuals also may not recognize the subtle cues leading up to a transition (i.e. students packing up their materials, teachers wrapping up their lecture, co-workers getting their lunches out of the refrigerator) and may not be prepared when it is time to move. Additionally, individuals with ASD are more likely to have restrictive patterns of behaviors (per the diagnostic criteria) that are hard to disrupt, thus creating difficulty at times of transitions. Finally, individuals with ASD may have greater anxiety levels which can impact behavior during times of unpredictability, as some transitions are.

When a teacher announces that an activity is finished and provides multi-step directions related to upcoming activities, students with ASD may not comprehend all of the verbal information. Difficulty sequencing information and recognizing relationships between steps of an activity can impact one’s ability to transition as well. Individuals also may not recognize the subtle cues leading up to a transition (i.e. students packing up their materials, teachers wrapping up their lecture, co-workers getting their lunches out of the refrigerator) and may not be prepared when it is time to move. Additionally, individuals with ASD are more likely to have restrictive patterns of behaviors (per the diagnostic criteria) that are hard to disrupt, thus creating difficulty at times of transitions. Finally, individuals with ASD may have greater anxiety levels which can impact behavior during times of unpredictability, as some transitions are.

Other factors, not unique to individuals with ASD, may impact transition behavior also. The ongoing activity may be more reinforcing to the individual than the activity he/she is moving to, or a second activity may be more demanding or unattractive to the individual (Sterling-Turner & Jordan, 2007). The individual may not want to start one activity or may not want to end another. In addition, the attention an individual receives during the transition process may be reinforcing or maintaining the difficult behavior.

The ongoing activity may be more reinforcing to the individual than the activity he/she is moving to, or a second activity may be more demanding or unattractive to the individual (Sterling-Turner & Jordan, 2007). The individual may not want to start one activity or may not want to end another. In addition, the attention an individual receives during the transition process may be reinforcing or maintaining the difficult behavior.

Preparation Strategies

Cueing individuals with ASD before a transition is going to take place is also a beneficial strategy. In many settings a simple verbal cue is used to signal an upcoming transition (i.e. “Time for a bath now”, “Put your math away”, or “Come to the break room for birthday cake”). This may not be the most effective way to signal a transition to individuals with ASD, as verbal information may not be quickly processed or understood. In addition, providing the cue just before the transition is to occur may not be enough time for an individual with ASD to shift attention from one task to the next. Allowing time for the individual with ASD to prepare for the transitions, and providing more salient cues that individuals can refer to as they are getting ready to transition may be more effective. Several visual strategies used to support individuals with ASD in preparation for a transition have been researched and will be discussed.

Allowing time for the individual with ASD to prepare for the transitions, and providing more salient cues that individuals can refer to as they are getting ready to transition may be more effective. Several visual strategies used to support individuals with ASD in preparation for a transition have been researched and will be discussed.

Visual Timer

It may be helpful for individuals with ASD to “see” how much time remains in an activity before they will be expected to transition to a new location or event. Concepts related to time are fairly abstract (i.e. “You have a few minutes”), often cannot be interpreted literally (i.e. “Just a second” or “We need to go in a minute”), and may be confusing for individuals on the spectrum, especially if time-telling is not a mastered skill. Presenting information related to time visually can assist in making the concepts more meaningful. Research indicated that the use of a visual timer (such as the Time Timer pictured below and available at timetimer. com) helped a student with autism transition successfully from computer time to work time at several points throughout the day (Dettmer, Simpson, Myles, & Ganz, 2000). This timer displays a section of red indicating an allotted time. The red section disappears as the allotted time runs out.

com) helped a student with autism transition successfully from computer time to work time at several points throughout the day (Dettmer, Simpson, Myles, & Ganz, 2000). This timer displays a section of red indicating an allotted time. The red section disappears as the allotted time runs out.

Visual Countdown

Another visual transition strategy to use prior to a transition is a visual countdown system. Like the visual timer, a visual countdown allows an individual to “see” how much time is remaining in an activity. The countdown differs, however, because there is no specific time increment used. This tool is beneficial if the timing of the transition needs to be flexible. Team members deciding to use this strategy need to make a countdown tool. This can be numbered or colored squares, as used in the photos below, or any shape or style that is meaningful to the individual. As the transition nears, a team member will take off the top item (i. e. the number 5) so the individual is able to see that only 4 items remain. The team member decides how quickly or slowly to remove the remaining items depending on when the transition will occur. Two minutes may elapse between the removal of number 3 and number 2, while a longer amount of time may elapse before the final number is removed. Once the final item is removed, the individual is taught that it is time to transition.

e. the number 5) so the individual is able to see that only 4 items remain. The team member decides how quickly or slowly to remove the remaining items depending on when the transition will occur. Two minutes may elapse between the removal of number 3 and number 2, while a longer amount of time may elapse before the final number is removed. Once the final item is removed, the individual is taught that it is time to transition.

Elements of Visual Schedules

The consistent use of visual schedules with individuals with ASD can assist in successful transitions. Visual schedules can allow individuals to view an upcoming activity, have a better understanding of the sequence of activities that will occur, and increase overall predictability. A number of studies have indicated that visual schedules used in classrooms and home settings can assist in decreasing transition time and challenging behaviors during transitions, as well as increase student independence during transitions (Dettmer et al. , 2000).

, 2000).

Use of Objects, Photos, Icons, or Words

Research has indicated that using a visual cue during a transition can decrease challenging behavior and increase following transition demands (Schmit, Alper, Raschke, & Ryndak, 2000). In one study, photo cues were used with a young boy with autism during transitions from one classroom activity to another, from the playground to inside the classroom, and from one room within the school to another (Schmit et al., 2000). At transition times, the staff presented the student with a photo of the location where he would be going. This allowed him to see where he was expected to go and provided additional predictability in his day. Other formats of information, such as objects, black-line drawings, or written words could be used to provide similar information to individuals. It is helpful for the individual to carry the information with him/her to the assigned location. This allows the individual to continually reference the information about where he/she is headed as the transition occurs. Once arriving at the destination, consider creating a designated “spot” for the individual to place the information, such as an envelope or small box. This indicates to the individual that he/she has arrived at the correct place.

Once arriving at the destination, consider creating a designated “spot” for the individual to place the information, such as an envelope or small box. This indicates to the individual that he/she has arrived at the correct place.

For example, if an individual is a concrete learner handing him an object that represents the area that he will be transitioning to may be most meaningful. If this student is to transition to work with a teacher, staff may hand him a task that will be used during the work time indicating it is time to transition to that location. Another student may be given a photo of the work with teacher area, while a third student may be given a written card that says “teacher”. When the student arrives at the teacher area, he may use the task in the activity or place the photo or word card in a designated spot. These cues provide advance notice to an individual and may assist with receptive language (understanding what is being said). Examples of a transition object (a book representing the reading center), a transition photo (picture of the teacher work area and the matching photo located at the teacher table), and a written card (the word “teacher” is given to the student and matched to a corresponding written cue at the teacher area) are below.

Showing a student one piece of visual information at a time during transitions may be helpful for many individuals with ASD. Other individuals may benefit, however, from seeing a sequence of two activities so they can better predict what will take place during the day. It is important for the team working with the individual to assess how much information is helpful at transition times. A “First/Then” sequence of information may be useful—as individuals can see what activity they are completing currently and what activity will occur next. This may help an individual transition to a location that is not preferred if he/she is able to see that a preferred activity is coming next. A “First/Then” should be portable and move with the individual as he/she transitions.

Use of Transition Cards

Other individuals with ASD may find that longer sequences of visual information are more effective in alleviating transition difficulties. These individuals might benefit from the use of a visual schedule that is located in a central transition area in the home, classroom, or employment setting. Instead of the information coming to the individual as discussed previously, now individuals have to travel to the schedule to get the object, photo, icon, or words that describe the next activity or location. If the schedule is centrally located, individuals need a cue to know when and how to transition to their schedules to get information. Using a consistent visual cue to indicate when it is time to transition is beneficial, as concrete cues can reduce confusion and help in developing productive transition routines. When it is time for an individual to access his visual schedule, present him/her with a visual cue that means “go check your schedule”. This cue can be the individual’s name, a photo of the individual, a picture of something that is meaningful to the individual, or any visual symbol the team selects. The individual is taught to carry the visual cue to his/her schedule, match the cue in a designated location and refer to the schedule for the next activity.

These individuals might benefit from the use of a visual schedule that is located in a central transition area in the home, classroom, or employment setting. Instead of the information coming to the individual as discussed previously, now individuals have to travel to the schedule to get the object, photo, icon, or words that describe the next activity or location. If the schedule is centrally located, individuals need a cue to know when and how to transition to their schedules to get information. Using a consistent visual cue to indicate when it is time to transition is beneficial, as concrete cues can reduce confusion and help in developing productive transition routines. When it is time for an individual to access his visual schedule, present him/her with a visual cue that means “go check your schedule”. This cue can be the individual’s name, a photo of the individual, a picture of something that is meaningful to the individual, or any visual symbol the team selects. The individual is taught to carry the visual cue to his/her schedule, match the cue in a designated location and refer to the schedule for the next activity. Using the visual cue regularly helps individuals predict the transition routine. The visual cue may be more salient and meaningful to the individual than repeated verbal cues. Examples of transition cues, including visuals that read “Check Schedule” and match to a corresponding pocket above daily schedules, and a picture of Barney that serves as a transition cue for a young girl (who also matches it to a corresponding pocket near her daily schedule) are below.

Using the visual cue regularly helps individuals predict the transition routine. The visual cue may be more salient and meaningful to the individual than repeated verbal cues. Examples of transition cues, including visuals that read “Check Schedule” and match to a corresponding pocket above daily schedules, and a picture of Barney that serves as a transition cue for a young girl (who also matches it to a corresponding pocket near her daily schedule) are below.

"Finished" Box

Another visual transition strategy that can be used before and during a transition is a “finished” box. This is a designated location where individuals place items that they are finished with when it is time to transition. When it is time to transition it is often helpful for individuals to have an assigned location to put materials prior to moving on to the next activity. The box may be located in the individual’s work area as well as in any center of the classroom or room in the home, and can be labeled with the word or a visual cue to indicate its purpose. Research indicated that the finished box, in combination with several other discussed visual strategies, was helpful during transitions from work time to free time for a young student with ASD (Dettmer et al., 2000). When work time or free time was finished (as indicated by the Time Timer) the student was instructed to put his items in the finished box before transitioning. This assisted in creating a clear and predictable transition routine which decreased transition time and increased positive behavior. Similarly, team members may decide that a “To Finish Later” box may be appropriate for an individual with ASD. This may used during transitions when an individual has not had time to complete an assigned activity. Often, individuals with ASD may prefer to complete an activity before moving on, and this may not be possible due to time constraints (i.e. family member has an appointment to attend, it is time to go to the cafeteria, the work shift is over). In these cases, establishing a loc ation where the individual knows he/she can find the materials to finish up at a later time or date may be helpful.

Research indicated that the finished box, in combination with several other discussed visual strategies, was helpful during transitions from work time to free time for a young student with ASD (Dettmer et al., 2000). When work time or free time was finished (as indicated by the Time Timer) the student was instructed to put his items in the finished box before transitioning. This assisted in creating a clear and predictable transition routine which decreased transition time and increased positive behavior. Similarly, team members may decide that a “To Finish Later” box may be appropriate for an individual with ASD. This may used during transitions when an individual has not had time to complete an assigned activity. Often, individuals with ASD may prefer to complete an activity before moving on, and this may not be possible due to time constraints (i.e. family member has an appointment to attend, it is time to go to the cafeteria, the work shift is over). In these cases, establishing a loc ation where the individual knows he/she can find the materials to finish up at a later time or date may be helpful.

Finished Box

Other Considerations When Planning for Transitions

Along with developing predictable and consistent transition routines, team members may also need to consider adjusting the activities that individuals are transitioning to and from if transition difficulty continues. Factors such as the length of an activity, the difficulty level, and the interest level of an individual all may contribute to transition issues. Similarly, if an area is too crowded, loud, over stimulating or averse for some reason, individuals may resist transitioning to that location. A review of environmental factors that could contribute to transition difficulties is also recommended. In addition, the sequence of activities may need to be reviewed. Team members may benefit from reviewing the activities required of the individual throughout the day and categorizing them as preferred, non-preferred, or neutral. If the individual has difficulty transitioning it may be wise, when possible, to strategically sequence certain activities so individuals are moving from non-preferred activities to preferred activities and from preferred activities to neutral activities. Though this certainly may not be possible for all of an individual’s transitions, it may alleviate some transition challenges.

Though this certainly may not be possible for all of an individual’s transitions, it may alleviate some transition challenges.

It is important for the team to continually assess how transitions impact individuals with ASD. Depending on the activity, environment, and the specific needs and strengths of the individual, a variety of transition strategies may be appropriate. Through the use of these strategies, research shows that individuals with ASD can more easily move from one activity or location to another, increase their independence, and more successfully participate in activities at home, school, and the workplace.

References

Dettmer, S., Simpson, R., Myles, B., & Ganz, J. (2000). The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15, 163-169.

Flannery, K. & Horner, R. (1994). The relationship between predictability and problem behavior for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 4, 157-176.

Journal of Behavioral Education, 4, 157-176.

Mesibov, G., Shea, V., & Schopler, E. (2005). The TEACCH® approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York, NY: Plenum Publishers.

Sainato, D., Strain, P., Lefebvre, D., & Rapp, N. (1987). Facilitating transition times with handicapped preschool children: A comparison between peer mediated and antecedent prompt procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20, 285-291.

Schmit, J., Alper, S., Raschke, D., & Ryndak, D. (2000). Effects of using a photographic cueing package during routine school transitions with a child who has autism. Mental Retardation, 38, 131-137.

Sterling-Turner, H. & Jordan, S. (2007). Interventions addressing transition difficulties for individuals with autism. Psychology in the Schools, 44, 681-690.

This article is an excerpt from a longer manuscript that can be found on the Autism Internet Modules, website: https://autisminternetmodules. org/.

org/.

Hume. (2008). Transition Time: Helping Individuals on the Autism Spectrum Move Successfully from One Activity to Another. The Reporter 13(2), 6-10.

7 Ways to Encourage A Smoother Transition in Young Children with Autism

Do you want to facilitate a smoother transition for your child or student with autism? I’m sure you have wondered why transition breakdowns occur so often and how you can help! These 7 strategies can help make transitions smoother for your little ones with autism. First things first. As an educator or therapist, it is imperative to start by building a positive relationship with your student. If you don’t have a positive relationship, helping a child do hard things (like transition) is going to be even more challenging. Next up, what is a transition? A transition can look like: a child moving between activities, moving between different areas in the classroom, or between different areas in or out of the building. Sometimes the breakdown in the transition occurs when it is a move from a highly motivating activity to a less preferred activity. Sometimes the transition might break down when a child doesn’t understand where they are going. At home, transitions can include: waking up in the morning, getting dressed, having to be done playing with certain toys, leaving the house to go to school, and getting ready for bed. Fostering a smoother transition requires some special techniques, consistency, and patience.

Sometimes the breakdown in the transition occurs when it is a move from a highly motivating activity to a less preferred activity. Sometimes the transition might break down when a child doesn’t understand where they are going. At home, transitions can include: waking up in the morning, getting dressed, having to be done playing with certain toys, leaving the house to go to school, and getting ready for bed. Fostering a smoother transition requires some special techniques, consistency, and patience.

WHY ARE TRANSITIONS HARD FOR LITTLE ONES WITH AUTISM?

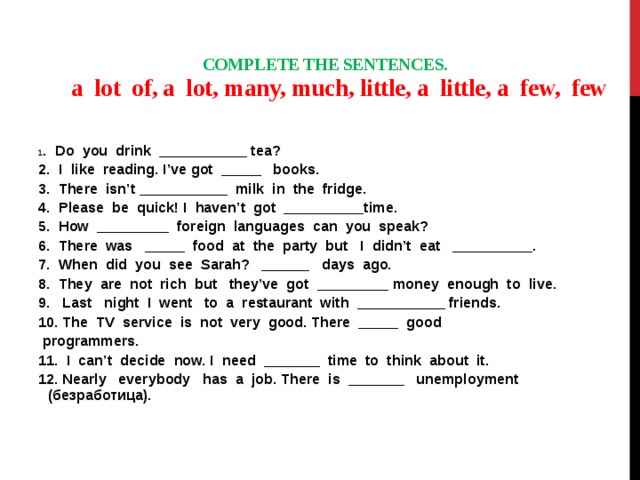

Transitions and change can be difficult for ALL children (and adults!). But, for autistic children who have the tendency to become very engaged in the activity that they are doing, transitions can trigger meltdowns. It can be hard to “switch gears”, especially when they thrive on consistency and routine. When autistic children are forced to switch gears without support, it can cause extreme stress and anxiety. Our job is to figure out how to prepare children for a smoother transition. We can help make transitions more predictable and routine-based. Some of the visual supports included in these tips can be found at no cost here.

We can help make transitions more predictable and routine-based. Some of the visual supports included in these tips can be found at no cost here.

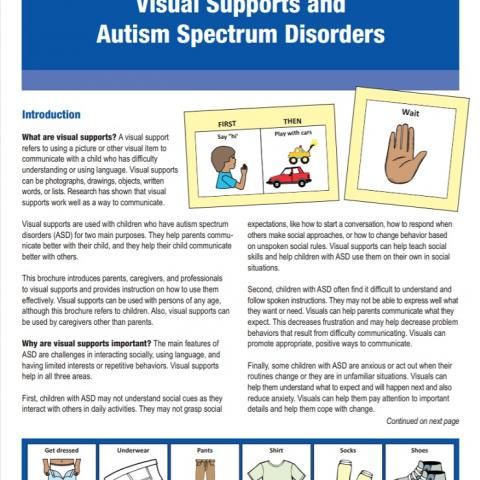

SUPPORTING TRANSITIONS IN CHILDREN WITH AUTISM

The best way to start thinking about how to support transitions in autism is to plan ahead, be prepared and be consistent. When the following strategies are implemented and used on a regular basis, it adds some structure and predictability to transitions. It doesn’t mean that you will never see another meltdown or resistance during transitions, but you should certainly see a reduction in stressed reactions during transitions. I always like to look at it like this…if I was sitting down reading a really good book and someone came and grabbed the book out of my hand and took it away without warning, I would be pretty upset. Quite often, this is how our students with autism feel….like we pulled out the rug from underneath them during many transitions throughout the day. We need to PREPARE our students/children for transitions ahead of time when possible. When you think about parenting a typically developing child, you might give a verbal warning of “two minutes, then clean up”. But, for children who aren’t processing auditory input effectively, this cue may be totally meaningless. That is where visual supports come into play. Each of the 7 strategies that I will share have a visual component to them. This is because we know that autistic children tend to be visual learners. We need to provide the preparation for transitions in a visual and predictable format. It is also very important to have these visual supports in several places around the classroom or home so they are easily accessible to you. Then, you will be prepared.

When you think about parenting a typically developing child, you might give a verbal warning of “two minutes, then clean up”. But, for children who aren’t processing auditory input effectively, this cue may be totally meaningless. That is where visual supports come into play. Each of the 7 strategies that I will share have a visual component to them. This is because we know that autistic children tend to be visual learners. We need to provide the preparation for transitions in a visual and predictable format. It is also very important to have these visual supports in several places around the classroom or home so they are easily accessible to you. Then, you will be prepared.

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #1:

Use a first-then board or visual schedule. A first-then visual support shows children the sequence of what they will be doing. It can be the starting place, before using a longer visual schedule. Simply bring the first-then board to your child/student, point to, and say what is on each picture. This is a great way to prepare them for the upcoming transition. For example: if my student is at the table eating a snack and I know we will be transitioning to a 1:1 learning time next, I will have the first-then near them and bring it to their attention a couple of times during snack. “First snack, then green table”. A visual schedule will have a longer sequence of activities. Many students start with a “first-then” board and then move on to a visual schedule that shows a sequence of 4-5 activities. Beyond that, many children are able to move to a half-day or full-day visual schedule.

This is a great way to prepare them for the upcoming transition. For example: if my student is at the table eating a snack and I know we will be transitioning to a 1:1 learning time next, I will have the first-then near them and bring it to their attention a couple of times during snack. “First snack, then green table”. A visual schedule will have a longer sequence of activities. Many students start with a “first-then” board and then move on to a visual schedule that shows a sequence of 4-5 activities. Beyond that, many children are able to move to a half-day or full-day visual schedule.

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #2:

Utilize a transition object. A transition object is just an object of any kind that can be carried in one hand by a child. It could be a toy or other favorite object (stuffed animal, matchbox car, brush, etc…). The student may have a favorite little toy that they bring to school, or it can be something from school. They could use the same transition object all day long, or you could offer something different for each transition that you anticipate could be difficult or stressful. Simply show your student the picture of what is next, and hold out the transition object for them to hold as they make that transition. Transition objects can reduce stress and anxiety, as well as shift the child’s attention from the activity they were doing.

Simply show your student the picture of what is next, and hold out the transition object for them to hold as they make that transition. Transition objects can reduce stress and anxiety, as well as shift the child’s attention from the activity they were doing.

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #3:

Use a wait mat. What do you do when your student is carrying a transition object, but it is getting in the way of paying attention during a 1:1 learning session? Using a “wait mat” can provide a structure/system and create a routine around letting go of the object during learning time. This is different from the all-done bucket (strategy #6) because the child doesn’t have to be all done holding the object. Instead, it is just a short break from holding it. Simply set the object on the wait mat and let the toy “watch” your student do his or her work. Once they are done, they can have the object back again!

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #4:

Give some wait time. Why are we always in such a hurry? I know, I know … in the classroom, you have some pressure to keep the schedule moving along. However, if your student has dropped to the floor and isn’t moving to the next activity or place, sometimes the best approach is to wait. Let them have their moment to be upset, regroup, and calm down. This is a great time for you to brainstorm what other strategy might help redirect them to thinking about something else. Sometimes they just need a hug. Sometimes they just need some quiet. There is no harm in just waiting them out for a while and moving on when they are ready. This is a very under-utilized strategy!

Why are we always in such a hurry? I know, I know … in the classroom, you have some pressure to keep the schedule moving along. However, if your student has dropped to the floor and isn’t moving to the next activity or place, sometimes the best approach is to wait. Let them have their moment to be upset, regroup, and calm down. This is a great time for you to brainstorm what other strategy might help redirect them to thinking about something else. Sometimes they just need a hug. Sometimes they just need some quiet. There is no harm in just waiting them out for a while and moving on when they are ready. This is a very under-utilized strategy!

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #5:

Use a timer. As an activity is coming to an end, it can be very helpful to use a timer to signal that it is finished, thus time to transition. This can help provide that consistency and predictability for students, which leads to a smoother transition A beep from an inexpensive kitchen timer works great (unless your student exhibits sensory defensiveness and the sound is too much for them). Usually, the kitchen timer works well because the beeping provides that cue to help the student shift their focus. You can use a visual timer if that is what works best for the child.

Usually, the kitchen timer works well because the beeping provides that cue to help the student shift their focus. You can use a visual timer if that is what works best for the child.

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #6:

Make and use an all-done bucket. The all-done bucket is a magical strategy! Once a child learns how to use it, it can help SO much! When it is time to be all done with a toy or an activity, bring the all-done bucket to your child or student and help them put the object in the container. This works with toys, tablets, playdough, crayons…almost anything! After you have facilitated the use of this consistently, all you will need to do is put the all-done bucket in front of your student and they automatically place the object into it. I’ve seen it work over and over again. The key is to introduce it and use it consistently so that it becomes a predictable routine. The use of an all-done bucket has greatly reduced stress over being “all done” with certain items with my students.

TRANSITIONS AND AUTISM STRATEGY #7:

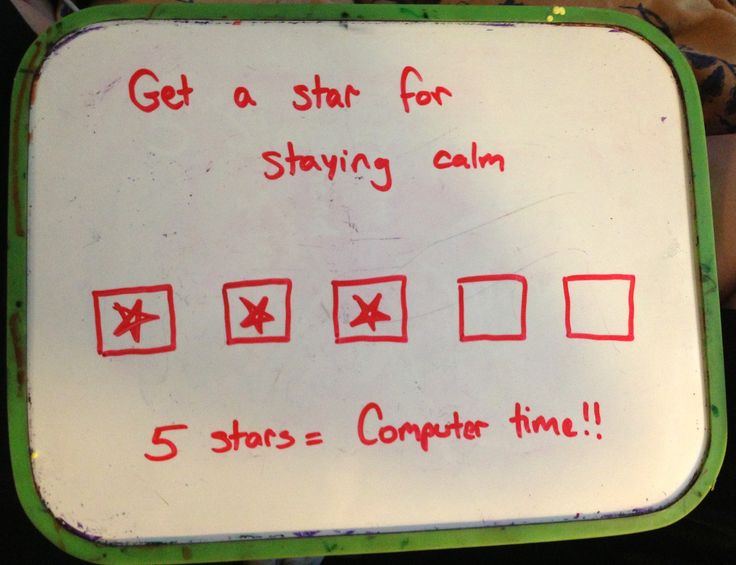

Use a star chart. This star chart is used to count down time. It is NOT a chart to “earn” or “lose” stars. Using a star chart is a form of duration mapping. It provides a visual way to countdown time to something. I use this every day on the playground and during our gym class when we have free time. This is how it works: take all of the stars off, and place the picture of what is next at the end of the chart (this could be a “check” to indicate “check schedule”, or it could be a picture of the activity that comes next). Then, as time goes on, my staff and I walk around and show our students, “one star….four more then ____” as we place a star on the chart. The nice thing about counting down time with the star chart is that we can make it go as slow or fast as we want to. We aren’t bound to a timer with an exact number of minutes. This comes in handy when a student is showing signs of stress and we need to end the activity on a positive note. We can hurry up and put the stars on and move to the next activity. The opposite is also true. If everything is going smoothly, we can extend the activity by putting the stars on more slowly. Continue putting the stars on and showing all of your students when each new star is on the chart. With repetition and consistency, they will start to understand what this means and it will better prepare them for the transition when it is time to shift gears. I LOVE this strategy!

We can hurry up and put the stars on and move to the next activity. The opposite is also true. If everything is going smoothly, we can extend the activity by putting the stars on more slowly. Continue putting the stars on and showing all of your students when each new star is on the chart. With repetition and consistency, they will start to understand what this means and it will better prepare them for the transition when it is time to shift gears. I LOVE this strategy!

COMBINING THESE STRATEGIES FOR SMOOTHER TRANSITIONS FOR STUDENTS WITH AUTISM

As you may have guessed, many of these strategies can be used in tandem when supporting transitions in your students with autism. For example: If I am working 1:1 with a student, I show them the first-then board. First learning time, then toy cars. Once they finish their work, I say “learning time is done, time for cars!”, as I refer to the first-then board again. After a few minutes, I set the timer for 2 minutes and say “two minutes, then check schedule”. Once the timer beeps, I offer the all-done bucket for them to put the cars in and hand them a picture of a “check” to go check their schedule.

Once the timer beeps, I offer the all-done bucket for them to put the cars in and hand them a picture of a “check” to go check their schedule.

Click here to grab a free set of visual supports that include the visuals for a first-then board, all done bucket, star chart, and wait mat!

Click here to watch the free FB Live mini-training on the topic of encouraging smoother transitions in young children with autism.

If you haven’t checked out these resources from Autism Little Learners yet, you definitely should! They will help your child or students with communication and self-regulation skills:

| Visual Communication Book DIY for Home or School |

| Self Regulation Activities for Little Learners |

If you haven’t grabbed up my FREE “Ultimate Guide For Targeting Language Skills In Young Children With Autism”, sign up to receive it now! This jam-packed guide will help you identify where to start with your student or child’s language skills!

If you found this blog post helpful, you may also like these blog topics from Autism Little Learners:

Click here to watch the Facebook Live Mini-Training titled “7 Ways To Encourage Smoother Transitions In Young Children With Autism”.

Click here to watch the Facebook Live Mini-Training titled “WH Questions For Speech Therapy – 3 Tips To Help”. The blog post and recommended resources can be found here.

Click here to watch the Facebook Live Mini-Training titled “How To Target Vocabulary Goals For Speech Therapy”. The blog post and recommended resources can be found here.

Click here to watch the Facebook Live Mini-Training titled “7 Steps To Teaching One Step Directions”. The blog post and recommended resources can be found here.

Click here to watch the Facebook Live Mini-Training titled ‘How To Use One Of The Best Hacks To Teacher Prepositions In Speech Therapy”. The blog post and recommended resources can be found here.

Click here to read the blog post titled, “Reframing Echolalia In Autism: It’s Not A Bad Thing!”

How to make transitions easier for a child with autism?

03.11.14

Eighteen ways to facilitate a change of lesson or place for a child with a raced

Author: Bek Oakley / BeC Oakley

Source: Snuggle Box

9000

. transitions - to another occupation, to another room, the change of seasons, or even the transition from wakefulness to sleep. Transitions are more predictable or slower than sudden changes, such as when you have to give up a walk because of a sudden rain, but they have their own special difficulties. Let's see what can be done to ease the transition for a child with autism:

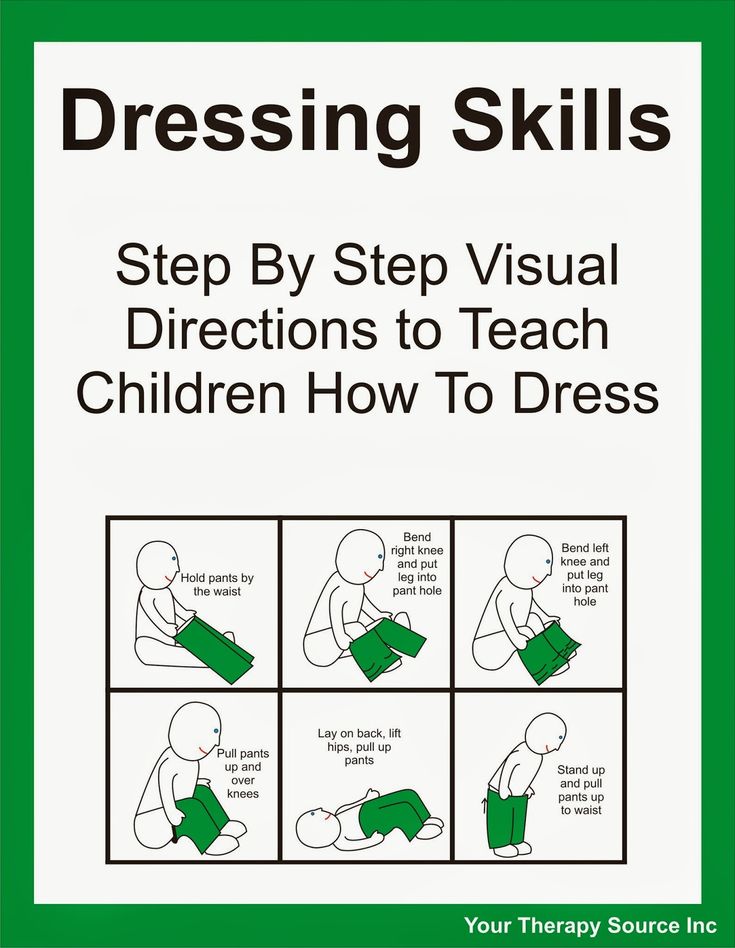

1. Divide any transition into several steps

Analyze the problem and break the transition into several small steps. This will help you understand what exactly the child's problems are related to. Let's take a simple example of a task with the transition from time at the computer to another activity:

1. Playing a computer game. Possible difficulties: Does he get frustrated when he fails? He is happy? Too excited?

2. Computer time is up. Possible complications: How will he know about it? Can he know in advance that time will soon run out? nine0003

3. Move away from the computer. Possible difficulties: Is the game still on? Does he have a routine for completing a game on the computer?

Possible difficulties: Is the game still on? Does he have a routine for completing a game on the computer?

4. Start another activity. Possible difficulties: Does he know where to go? Can he still hear sounds from the computer game?

5. Start another activity. Possible difficulties: Does he know what to do? Does he have everything he needs?

2. Show your child that change can be for the better

Choose two activities your child loves and practice transitioning between them. Teach your child to understand what the transition from one activity to another is when it comes, and how you feel when it happens. Associate transitions with rewards and lack of stress so that the child can focus on what indicates transition and understand that change can be for the better. (Also see the article How to teach a child with autism to accept unexpected changes?). nine0003

3. Make the transition smooth

Sometimes you can avoid abrupt and frightening transitions by making the change of activity implicit, blurring the boundaries between two activities, and reducing the number of steps between them. For example, if the child is playing on the floor, let him take his toys and bring them to the kitchen table while you prepare breakfast, and when the porridge is ready, put them away. First, go from trousers to long shorts, and then to short summer ones.

For example, if the child is playing on the floor, let him take his toys and bring them to the kitchen table while you prepare breakfast, and when the porridge is ready, put them away. First, go from trousers to long shorts, and then to short summer ones.

4. Be prepared in advance

However, you already know about this. The best way to deal with transitions is to be aware of them ahead of time. Get into the habit of thinking ahead for the day, the week, and the month ahead and identifying when transitions might occur.

5. Use a Visual Schedule

This is the single most important tool for helping autistic children cope with any kind of change. The daily activity list helps the child always know what to expect, shows him the sequence of events and marks the transition points. (Also see the article What is a visual schedule for a child with autism?). nine0003

6. Make the end of the activity obvious

Transitioning to a new activity can be difficult if you don't know when the old one is over. Look for ways to visually show your child when the activity is over. For example, take a picture off the visual schedule and put it in the “done” bin, or take a picture of what a completed task looks like and show it to your child.

Look for ways to visually show your child when the activity is over. For example, take a picture off the visual schedule and put it in the “done” bin, or take a picture of what a completed task looks like and show it to your child.

7. Use transition prompts

Warn the child in advance and many times that the situation will soon change. Use a visual, clear and understandable signal for each transition. For example, put on a song about "Bob the Builder" when playtime is over and it's time to collect toys. Count down the last ten minutes of the lesson on the board before recess. nine0003

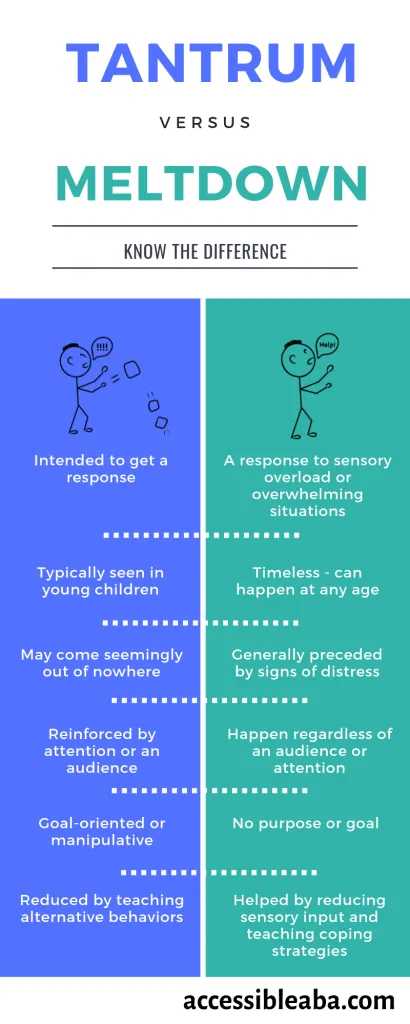

8. Avoid verbal cues

Listening comprehension is a weakness for many autistic children, so try to make more use of visual and physical cues. Tap the child's foot when it's time to get up, put sheets of paper with painted footprints on the floor to show him where to go.

9. Use a visual timer

Time is a very abstract idea, so making time visible can help you prepare for the transition ahead. The best way to show your child how time passes is with devices such as a visual timer, where time literally "disappears" as the time ticks down. nine0003

The best way to show your child how time passes is with devices such as a visual timer, where time literally "disappears" as the time ticks down. nine0003

10. Mark boundaries and places for different activities

Moving from one task to another will be easier if you know where to go and what to do there. If the child has to sit on the carpet, then mark the place where he should sit, or show him a map of places where he can play during a big break.

11. Teach Your Child Words for Transition

Before you start explaining transition to children, they need to understand the basic concepts of time—first, then, after that, now, later. Use these words as often as possible and play simple games with your child to reinforce these concepts:

- First you roll the ball to me, then I roll it to you.

- First you watch a cartoon about a steam train, and then we bake cookies.

— First your brother bathes, and then you.

- After you wash your hands, you can drink.

- Let's put the toys in a row ... First the bear, then Nemo, then Spiderman.

12. Teach tangible time

Understanding time is not limited to being able to tell time by the clock. It is important for children to get a feel for how long five or ten minutes are, and this will help them cope with the transition better than just telling them to do something before 10:30. nine0003

Show your child what five minutes look like on a visual timer and watch the countdown with your child. Measure the time it takes you to move from one class to another or eat a sandwich. This is a good time to use a child's special interests - talk about how long each episode of SpongeBob lasts, or how long it takes to complete one lap in a racing video game. Thus, the next time you warn your child that they only have five minutes before moving on to another activity, you can simply say “this is taking as long as…”

13. Use an object to transition

Use an object to transition

A child can reduce the stress of transition by taking a specific object with them. There are several reasons for this:

- The contrast between activities and places is smoothed out. For example, a child may take their favorite CD with them when they go from home to their car.

— The situation is becoming more predictable. For example, every time a child picks up a brush, it's time to go to drawing class.

- An object can serve as a consolation. When a child holds something familiar, the new situation does not seem so scary to him. nine0003

- A hint about the next lesson. For example, a child takes with him a photograph of the room where he needs to come.

- Signal about the end of the transition. For example, a child comes to the right room with a photo and drops the photo into a special box.

- A reminder of what to do. For example, a child is holding a book and it reminds him that he is going to the library.

- The transition item helps the child figure out what to do, especially if he has difficulty understanding your instructions due to speech difficulties. nine0003

14. Give your child more time

The process of pausing activities, shifting attention, and moving on to another activity can take longer for an autistic child, so don't rush them during transitions. Children with heightened sensory sensitivity may also take longer to adjust to new sensory stimuli.

15. Watch for possible signs of stress

Nobody performs best when they can't handle stress, so be aware of the potential signs in your child and always watch for them. Early signs of stress need to intervene as soon as possible and provide the child with more help, or reduce annoying sensory signals. nine0003

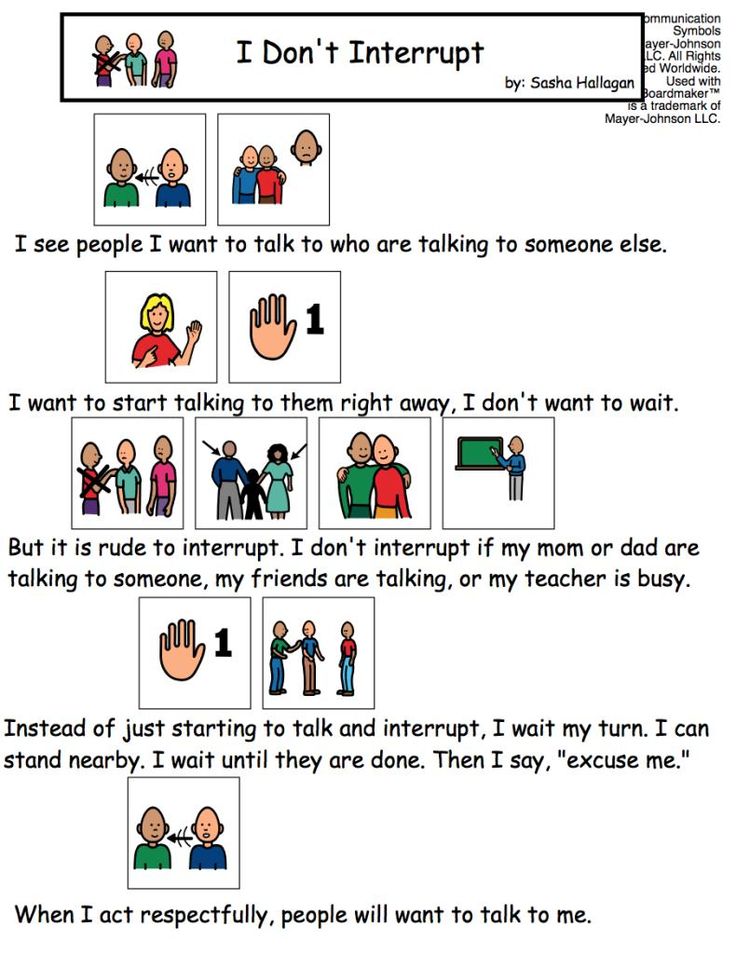

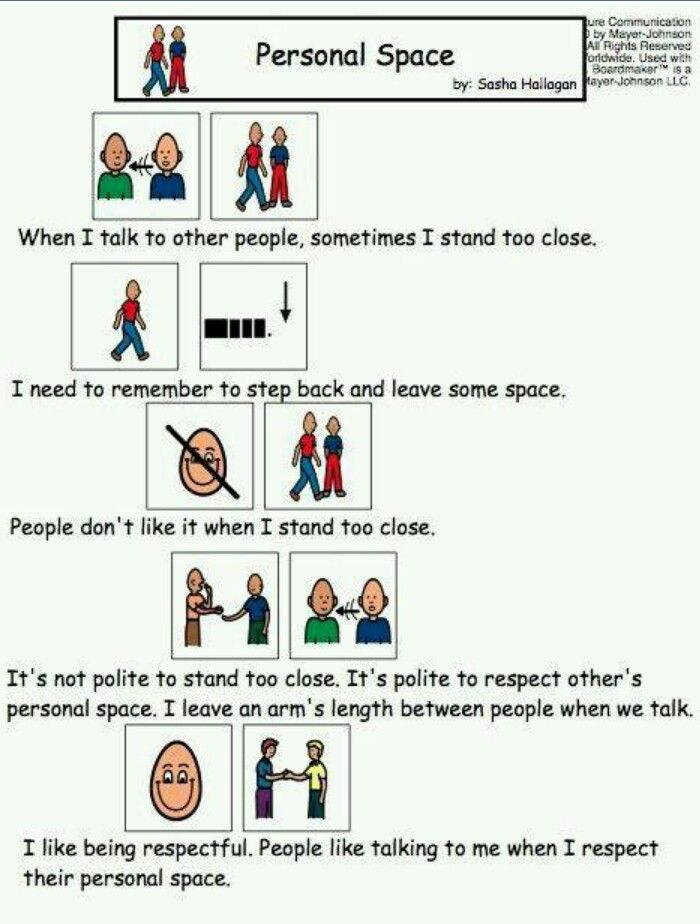

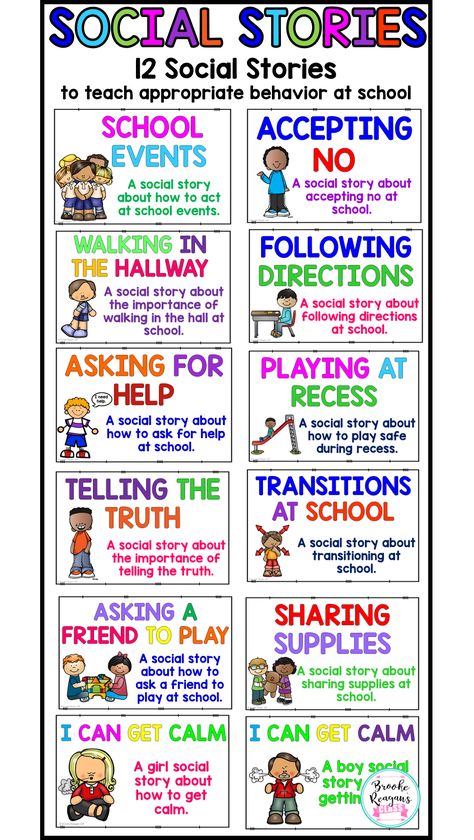

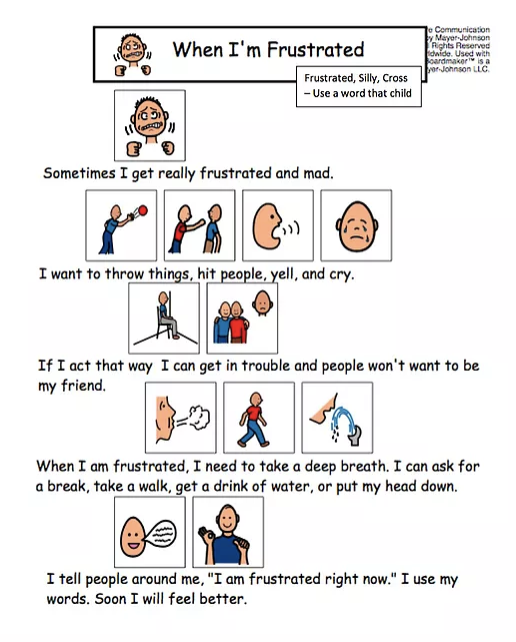

16. Write Social Stories

Transition is often stressful because it involves abandoning the familiar and safe in favor of the new and frightening. So try to turn an unknown situation into a familiar one with a pre-written picture story. Explain to the child when the change will occur, how he will know it is time to finish the old activity, and what the new activity will be like. (Also see the article “How to teach children with autism using social stories?”). nine0003

So try to turn an unknown situation into a familiar one with a pre-written picture story. Explain to the child when the change will occur, how he will know it is time to finish the old activity, and what the new activity will be like. (Also see the article “How to teach children with autism using social stories?”). nine0003

17. Practice Stopping Activities

The first step in shifting attention—stopping what you are currently doing—is very difficult for autistic children, and this is one of the reasons why transitions are difficult for them. This feature also affects their ability to perceive what is happening around them and participate in communication, so this is an important skill to work on.

The whole trick is to switch attention from the current activity to be associated with receiving some kind of reward. For example, keep computer games on the other side of the room, and then the child will have to stop playing in order to get a new game. Or keep the pieces of the puzzle with you so that the child has to stop and look at you every time he needs a new piece. nine0003

nine0003

18. Avoid transitions

The easiest way to deal with transitions is to reduce the number of transitions throughout the day. The child will experience less stress and will be able to handle the remaining transitions more easily, and it will be easier for you too. Understanding how to get rid of unnecessary transitions is quite simple, it is difficult to plan a day in advance so that you can understand what is ahead of you.

Make a plan for the day and highlight the transitions in it, and then get rid of all that you can get rid of. If your overly sensitive child doesn't like to change, then don't force him to change into casual clothes after school, have him put on his pajamas right away, or have him wear his school uniform until it's time for bed. If you can outwit circumstances, then do it with a clear conscience! nine0003

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Parenting children with autism

How to help a child with autism become more independent?

06/13/16

Many autistic children have problems with excessive dependence on adults and lack of initiative when interacting with people

Author: Tameika Meadows

Source: I Love ABA

Parents of children with special needs learn many "specialties". They are the interpreters of their child, and his refuge, and those who "explain" his behavior to others, and waiters with cooks, and so on. Small and non-speaking children with developmental disabilities really constantly need the help of those who know the child well and can become an intermediary in his interaction with other people. Mom and dad are the kind of people who know that stripping in public means "I need to go to the toilet" and throwing a bottle means "More please." This is a natural and important stage in the relationship between parents and child. nine0003

nine0003

However, there comes a time when the natural desire of loving parents to intervene and make life easier for the child becomes an obstacle to his learning and development. As with teaching prompts, "mind reading" weakens the child's motivation to communicate with others. That's the way the behavior works. We are all human, and we all tend to choose the easiest option.

When I work with children, I often see a situation where it is obvious that although parents adore and love their child, they make life TOO MUCH easier for him. For example, a mother explains to me that she wants the child to become more independent, and at the same time she spoon-feeds her four-year-old son. nine0003

I understand that such active intervention in a child's life is dictated only by love, and that this is the reaction of parents to serious violations in the child's development. However, there comes a time when both parents and professionals must take a step back and force the child to behave more independently. I have never met parents who would like their children to be more dependent on them ... usually it's just the opposite. And the first step in encouraging a child's independence is to analyze your own behavior and understand when your helping a child is excessive. nine0003

I have never met parents who would like their children to be more dependent on them ... usually it's just the opposite. And the first step in encouraging a child's independence is to analyze your own behavior and understand when your helping a child is excessive. nine0003

All children in certain situations can be proactive or reactive. Our task is to make the child more and more proactive, and less and less reactive. Here are some examples to explain the difference:

Initiative child

- The child is hungry, so he is looking for an adult and asks him. For example, he says: “I want cookies.”

- The child is bored so he turns on the TV and sits down to watch it.

- Dad forgets to pour juice for his child during meals. The child makes eye contact with dad and points to the refrigerator as a request for juice. nine0003

Reactive child

- The child is hungry, so he starts crying and expressing his annoyance with unwanted behavior. After some time, someone guesses that the child may be hungry.

- The child is bored, so he goes after mom or dad and asks for pens. Further entertainment of the child depends on the parents.

- Dad forgets to give his child juice during meals. The child begins to cry bitterly and refuses to eat.

In the latter case, the child depends on other people, or he communicates his needs through unwanted behavior. These children rely on adults to read their minds and identify their needs. Very often, this leads to a game I like to call "Guess what I want!", where mom or dad is desperately trying to figure out what will make the child stop crying or other problematic behavior. nine0003

The initiating child will either try to satisfy his needs on his own, or he will turn to an adult for help. The child is able to use verbal or non-verbal means of communication that will be understood by different people, and not just parents.

When teaching a child with autism, it is important to always aim for more than the child's current skill level. Depending on what the child is currently capable of, there is always a way to help the child become more independent in regards to that skill. nine0003

Depending on what the child is currently capable of, there is always a way to help the child become more independent in regards to that skill. nine0003

A common example of proactive or reactive behavior I see during toilet training. Very often parents tell me that their child is fully toilet trained. When I ask how a child wants to go to the toilet, the parents answer: “I don’t know” or “We just understand it”, and no ... such a child is not fully toilet trained. If the child just gets up and goes to the toilet, then what to do in public places? How can your child tell you to go to the bathroom when you are at the mall? If you left your child with a new nanny, will she be able to tell when he wants to go to the toilet? Toilet skills include the ability to communicate to adults about the need to go to the toilet, as well as to ask to use the toilet in an unfamiliar place. nine0003

Helping your child move from reactive to proactive behavior will help them become more independent. The ability to initiate interaction is a critical skill for success in school, in peer groups, and almost everywhere in life. Here are some helpful tips on how to properly make life difficult for your child with autism:

The ability to initiate interaction is a critical skill for success in school, in peer groups, and almost everywhere in life. Here are some helpful tips on how to properly make life difficult for your child with autism:

Don't be afraid to be independent: I understand that it's scary to let a three-year-old child use a knife himself, and it's scary to teach a six-year-old child to unbuckle a seat belt in a car. But you can encourage independence within reason and in safe situations. Just because your son can unfasten his seatbelt doesn't mean he can do it while the car is in motion. Along with independence, teach your child boundaries and rules. nine0003

Play dumb: This is the easiest way to gradually decrease the level of help and prompting for your child. When a child comes to you crying and with outstretched arms, look at him puzzled and act as if you do not understand what he needs. Depending on the child's skills, prompt him to make a verbal request, use PECS, pointing, and so on. For example, require the child to say "up" before you pick him up. Crying, pant tugging, or kicking your leg should not be encouraged. Stop guessing the child's needs and satisfy them, pretend that you do not understand what he wants, so that he was motivated to try another way. nine0003

For example, require the child to say "up" before you pick him up. Crying, pant tugging, or kicking your leg should not be encouraged. Stop guessing the child's needs and satisfy them, pretend that you do not understand what he wants, so that he was motivated to try another way. nine0003

Take your time: Parents often tell me that it is easier for them to dress, wash or feed their child. I understand that this is easier and faster, but in the long run it makes the child too dependent on you. Accept that sometimes you will be late. Yes, you may have to wait 35 minutes for the child to put on a shirt, or you may have to wait for a whole row while the child brushes his teeth. Sometimes you have to make sacrifices that will pay off in the future. Start small, like giving your child a plate, a spoon, but not a box of cereal. Using your child's level of communication, tell them how to ask for cereal. Even if you spend 15 minutes more on breakfast as a result, in the end, you will teach your child to take the initiative. Let the teacher know that you are working on getting yourself to school in the morning, and therefore your child may be a little late for a few days. nine0003

Let the teacher know that you are working on getting yourself to school in the morning, and therefore your child may be a little late for a few days. nine0003

Wait: It's not just the parents who have problems with this, I also often make this mistake. Sometimes we want a child to be successful so badly that we step in and provide a hint. The problem is that this can lead to dependency on hints, and this hinders the development of initiative. The next time you ask your child to do something, try waiting 10-20 seconds. I know it seems like an eternity, but some children with autism have problems with hearing information, so they need time to understand what you said and decide on a course of action before you fulfill your request. I'm not suggesting you do this all the time, but it's important that you don't get in the habit of jumping in to help your child. If you just told your daughter to tie her shoelaces, then sit next to her and wait 15 seconds before giving any prompt.