How to help a child with anxiety and anger

Helping your child with anger issues

Anger is a normal and useful emotion. It can tell children when things are not fair or right.

But anger can become a problem if a child's angry behaviour becomes out of control or aggressive.

Why is your child so angry?

There are lots of reasons why your child may seem more angry than other children, including:

- seeing other family members arguing or being angry with each other

- friendship problems

- being bullied – the Anti-Bullying Alliance has information on bullying

- struggling with schoolwork or exams

- feeling very stressed, anxious or fearful about something

- coping with hormone changes during puberty

It may not be obvious to you or your child why they're feeling angry. If that's the case, it's important to help them work out what might be causing their anger.

Read our tips on talking to children about feelings.

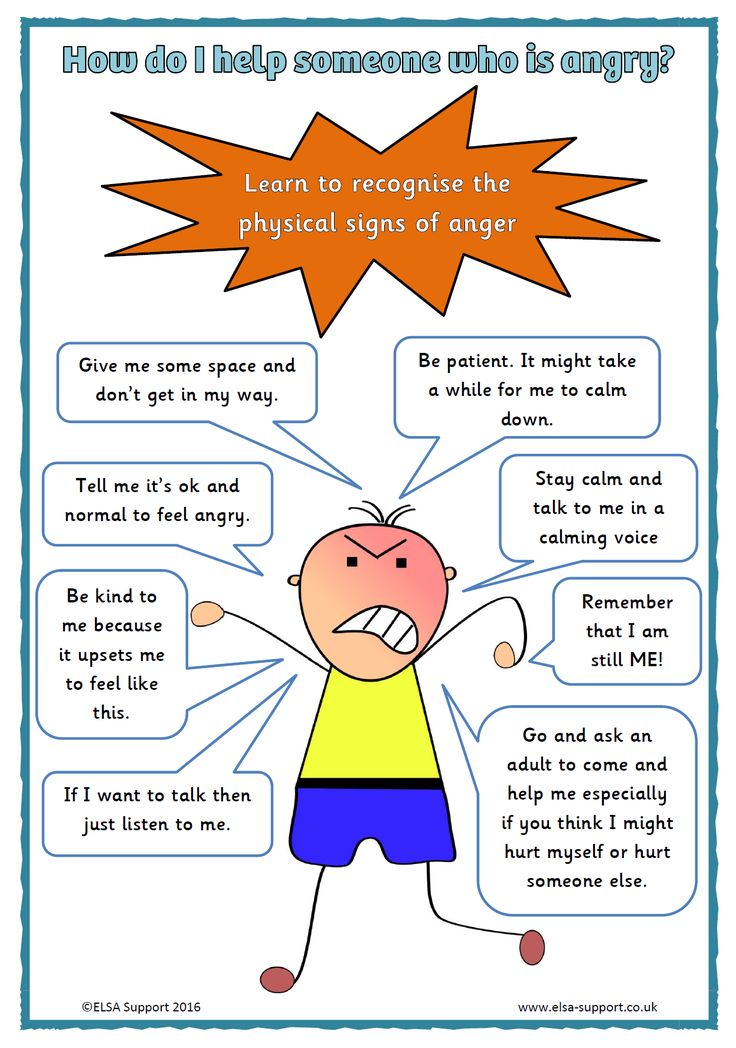

Tackle anger together

Team up with your child to help them deal with their anger. This way, you let your child know that the anger is the problem, not them.

With younger children, this can be fun and creative. Give anger a name and try drawing it – for example, anger can be a volcano that eventually explodes.

How you respond to anger can influence how your child responds to anger. Making it something you tackle together can help you both.

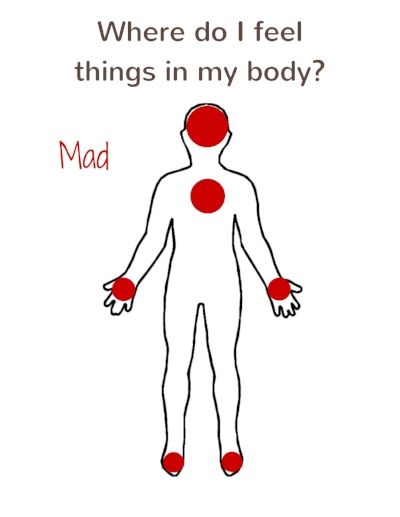

Help your child spot the signs of anger

Being able to spot the signs of anger early can help your child make more positive decisions about how to handle it.

Talk about what your child feels when they start to get angry. For example, they may notice that:

- their heart beats faster

- their muscles tense

- they clench their teeth

- they make a fist

- their stomach churns

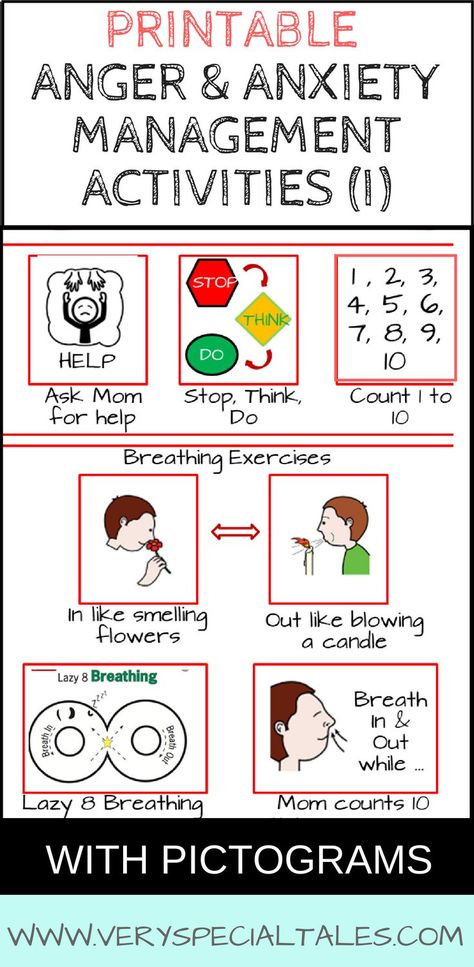

Anger tips for your child

Work together to try to find out what triggers the anger. Talk about helpful strategies for managing anger.

You could encourage your child to:

- count to 10

- walk away from the situation

- breathe slowly and deeply

- clench and unclench their fists to ease tension

- talk to a trusted person

- go to a private place to calm down

If you see the early signs of anger in your child, say so. This gives them the chance to try their strategies.

This gives them the chance to try their strategies.

Encourage regular active play and exercise

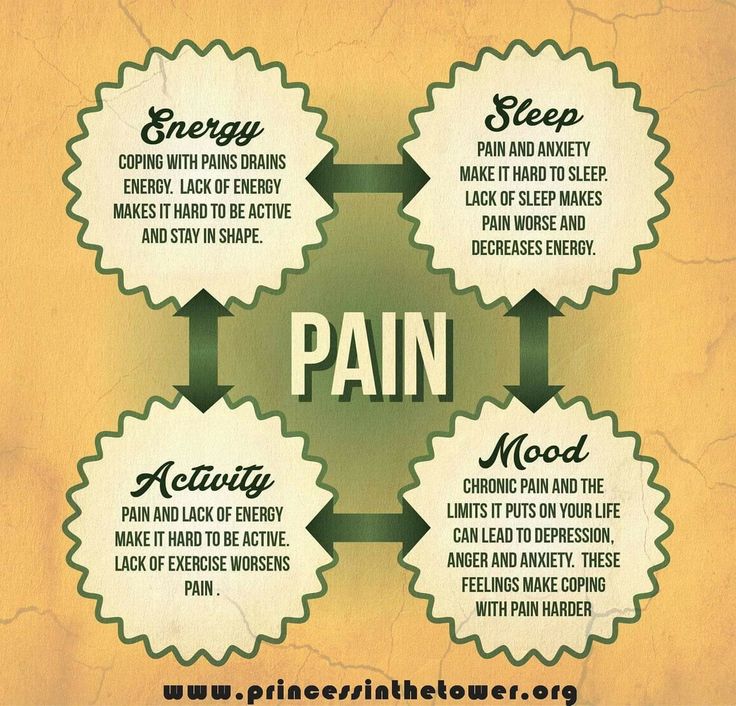

Staying active can be a way to reduce or stop feelings of anger. It can also be a way to improve feelings of stress, anxiety or depression,

For older children or young people, this could be simple activities, such as:

- a short walk

- jogging or running

- cycling

Read more about physical activity for children and young people.

Be positive

Positive feedback is important. Praise your child's efforts and your own efforts, no matter how small.

This will build your child's confidence in their ability to manage their anger. It will also help them feel that you're both learning together.

It will also help them feel that you're both learning together.

When to seek help for anger in children

If you're concerned your child's anger is harmful to them or people around them, you could talk to a:

- GP

- health visitor

- school nurse

If necessary, a GP may refer your child to a local children and young people's mental health service (CYPMHS) for specialist help.

CYPMHS is used as a term for all services that work with children and young people who have difficulties with their emotional or behavioural wellbeing.

You may also be able to refer your child yourself without seeing a GP.

Read more about accessing mental health services.

Further help and support for anger in children

For more support with anger in children, you could phone the YoungMinds parents' helpline free on 0808 802 5544 (9. 30am to 4.00pm, Monday to Friday).

30am to 4.00pm, Monday to Friday).

Other sources of help and support include:

- YoungMinds: parent's guide to responding to anger

- YoungMinds: information for children about dealing with anger

- MindEd for families: anger and aggression in children

If you have older children, find out more about talking to teenagers and coping with your teenager.

The Health for Teens website also has more about anger management

Page last reviewed: 11 February 2020

Next review due: 11 February 2023

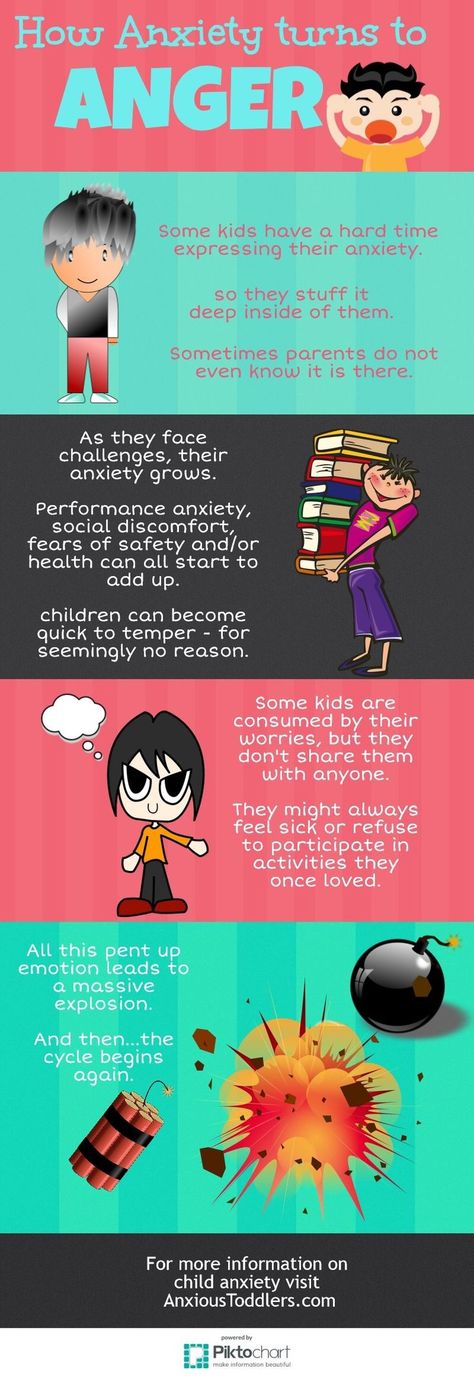

How Anxiety Leads to Problem Behavior in Children

A 10-year-old boy named James has an outburst in school. Upset by something a classmate says to him, he pushes the other boy, and a shoving-match ensues. When the teacher steps in to break it up, James goes ballistic, throwing papers and books around the classroom and bolting out of the room. He is finally contained in the vice principal’s office, where staff members try to calm him down. Instead, he kicks the vice principal in a frenzied effort to escape. The staff calls 911, and James ends up in the Emergency Room.

He is finally contained in the vice principal’s office, where staff members try to calm him down. Instead, he kicks the vice principal in a frenzied effort to escape. The staff calls 911, and James ends up in the Emergency Room.

To the uninitiated, James looks like a boy with serious anger issues. It’s not the first time he’s flown out of control. The school insists that his parents pick him up and take him home for lunch every day because he’s been banned from the cafeteria.

Unrecognized anxiety

But what’s really going on? “It turns out, after an evaluation, that he is off the charts for social anxiety,” reports Jerry Bubrick, PhD, a child psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. “He can’t tolerate any — even constructive — criticism. James is terrified of being embarrassed, so when a boy says something that makes him uncomfortable, he has no skills to deal with it, and he freaks out. Flight or fight.”

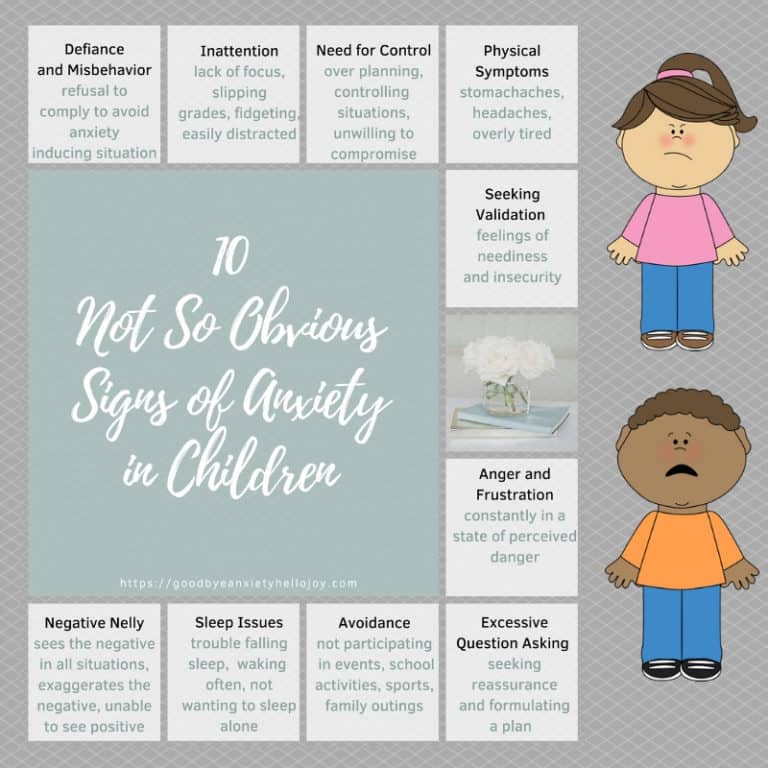

James’s story illustrates something that parents and teachers may not realize — that disruptive behavior is often generated by unrecognized anxiety. A child who appears to be oppositional or aggressive may be reacting to anxiety—anxiety they may, depending on their age, not be able to articulate effectively, or not even fully recognize.

A child who appears to be oppositional or aggressive may be reacting to anxiety—anxiety they may, depending on their age, not be able to articulate effectively, or not even fully recognize.

“Especially in younger kids with anxiety you might see freezing and clinging kind of behavior,” says Rachel Busman, PsyD, a clinical psychologist, “but you can also see tantrums and complete meltdowns.”

A great masquerader

Anxiety manifests in a surprising variety of ways in part because it is based on a physiological response to a threat in the environment, a response that maximizes the body’s ability to either face danger or escape danger. So while some children exhibit anxiety by shrinking from situations or objects that trigger fears, some react with overwhelming need to break out of an uncomfortable situation. That behavior, which can be unmanageable, is often misread as anger or opposition.

“Anxiety is one of those diagnoses that is a great masquerader,” explains Laura Prager, MD, director of the Child Psychiatry Emergency Service at Massachusetts General Hospital. “It can look like a lot of things. Particularly with kids who may not have words to express their feelings, or because no one is listening to them, they might manifest their anxiety with behavioral dysregulation.”

“It can look like a lot of things. Particularly with kids who may not have words to express their feelings, or because no one is listening to them, they might manifest their anxiety with behavioral dysregulation.”

The more commonly recognized symptoms of anxiety in a child are things like trouble sleeping in their own room or separating from their parents, avoidance of certain activities. “Anyone would recognize those symptoms,” notes Dr. Prager, co-author of Suicide by Security Blanket, and Other Stories from the Child Psychiatry Emergency Service. But in other cases the anxiety can be hidden.

“When the chief complaint is temper tantrums, or disruption in school, or throwing themselves on the floor while shopping at the mall, it’s hard to know what it means,” she explains. “But it’s not uncommon, when kids like that come in to the ER, for the diagnosis to end up being a pretty profound anxiety disorder.”

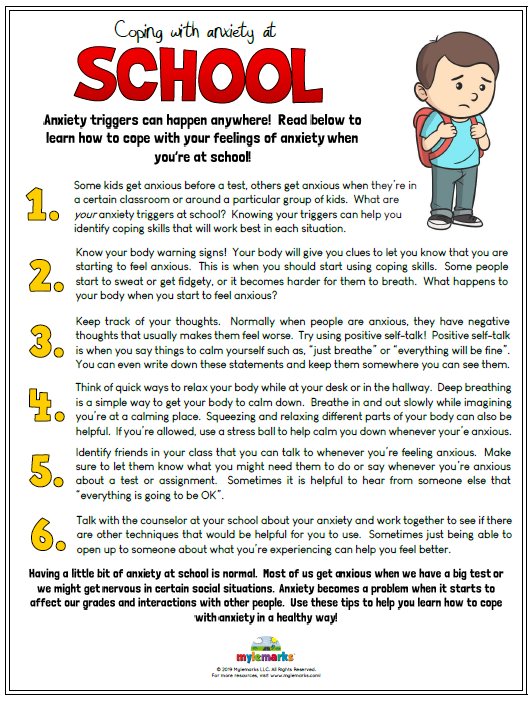

Problems at school

It’s not uncommon for children with serious undiagnosed anxiety to be disruptive at school, where demands and expectations put pressure on them that they can’t handle. And it can be very confusing to teachers and other staff members to “read” that behavior, which can seem to come out of nowhere.

And it can be very confusing to teachers and other staff members to “read” that behavior, which can seem to come out of nowhere.

Nancy Rappaport, MD, a Harvard Medical School professor who specializes in mental health care in school settings, sees anxiety as one of the causes of disruptive behavior that makes classroom teaching so challenging. “The trouble is that when kids who are anxious become disruptive they push away the very adults who they need to help them feel secure,” notes Dr. Rappaport. “And instead of learning to manage their anxiety, they end up spending half the day in the principal’s office.”

Dr. Rappaport sees a lot of acting out in school as the result of trauma at home. “Kids who are struggling, not feeling safe at home,” she notes, “can act like terrorists at school, with fairly intimidating kinds of behavior.” Most at risk, she says, are kids with ADHD who’ve also experienced trauma. “They’re hyper-vigilant, they have no executive functioning, they misread cues and go into combat. ”

”

When a teacher is able to build a relationship with a child, to find out what’s really going on with them, what’s provoking the behavior, she can often give them tools to handle anxiety and prevent meltdowns. In her book, The Behavior Code: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Teaching the Most Challenging Students, Dr. Rappaport offers strategies kids can be taught to use to calm themselves down, from breathing exercises to techniques for distracting themselves.

“When a teacher understands the anxiety underlying the opposition, rather than making the assumption that the child is actively trying to make her miserable, it changes her approach,” says Dr. Rappaport, “The teacher is able to join forces with the child himself and the school counselor, to come up with strategies for preventing these situations.”

If it sounds labor-intensive for the teacher, it is, she notes, but so is dealing with the aftermath of the same child having a meltdown.

Anxiety confused with ADHD

Anxiety also drives a lot of symptoms in a school setting that are easily misconstrued as ADHD or defiant behavior.

“I’ll see a child who’s having difficulty in school: not paying attention, getting up out of their seat all the time, asking a lot of questions, going to the bathroom a lot, getting in other kids’ spaces,” explains Dr. Busman. “The behavior is disrupting other kids, and is frustrating to the teacher, who’s wondering why they ask so many questions, and why they’re so wrapped up in what other kids are doing, whether they’re following the rules.”

People tend to assume what’s happening with this child is ADHD inattentive type, but it’s commonly anxiety. Kids with OCD, mislabeled as inattentive, are actually not asking all those questions because they’re not listening, but rather because they need a lot of reassurance.

How to identify anxiety

“It probably occurs more than we think, either anxiety that looks disruptive or anxiety coexisting with disruptive behaviors,” Dr. Busman adds. “It all goes back to the fact that kids are complicated and symptoms can overlap diagnostic categories, which is why we need to have really comprehensive and good diagnostic assessment.”

Busman adds. “It all goes back to the fact that kids are complicated and symptoms can overlap diagnostic categories, which is why we need to have really comprehensive and good diagnostic assessment.”

First of all, good assessment needs to gather data from multiple sources, not just parents. “We want to talk to teachers and other people involved with the kid’s life,” she adds, “because sometimes kids that we see are exactly the same at home and at school, sometimes they are like two different children.”

And it needs to use rating scales on a full spectrum of behaviors, not just the area that looks the most obvious, to avoid missing things.

Dr. Busman also notes that a child with severe anxiety who’s struggling in school might also have attention or learning issues, but they might need to be treated for the anxiety before they can really be evaluated for those. She uses the example of a teenager with OCD who is doing terribly in school. “She’s ritualizing three to four hours a day, and having constant intrusive thoughts — so we need to treat that, to get the anxiety under control before we ask, how is she learning?”

How to calm the anger of a short-tempered child

Every parent wants their child to be a calm boy or girl. But there are children who have already learned to solve their problems only with the help of aggression. Parents should help the child identify the source of anger and teach them how to deal with it. It takes time to acquire new habits, especially when it comes to short tempers.

But there are children who have already learned to solve their problems only with the help of aggression. Parents should help the child identify the source of anger and teach them how to deal with it. It takes time to acquire new habits, especially when it comes to short tempers.

Every child has certain experiences and unresolved conflicts that develop into outbursts of anger. For example, a child may feel unappreciated in the family or suffer from low self-esteem in the classroom. Adult task - identify the causes of the child's anger , which can be expressed by various negative experiences: irritation, anxiety, disappointment, etc.

For many children, anger manifests itself in the fact that they fight, scream, hit and bite, they may bang their heads against the wall, because they simply do not know how to express their feelings in another way. For this child it is necessary to teach to recognize emotions . A few examples: angry, frustrated, enraged, agitated, enraged, anxious, tense, nervous, restless, annoyed, enraged . When your child is angry, use these words so that he can apply them later: "You seem really angry, do you want to talk about it?", "You seem annoyed, do you want this to go away?"

When your child is angry, use these words so that he can apply them later: "You seem really angry, do you want to talk about it?", "You seem annoyed, do you want this to go away?"

To make the child behave differently, teach him to conduct an internal dialogue . Teach your child to say a simple affirmative phrase that he will repeat to himself in any stressful situation, for example: “stop and calm down”, “don't lose your temper”, “I can handle it”.

Teach your child to let go of anger . Invite the child to draw or write on a piece of paper what pisses him off, and then tear this sheet into small pieces and “throw out the anger.”

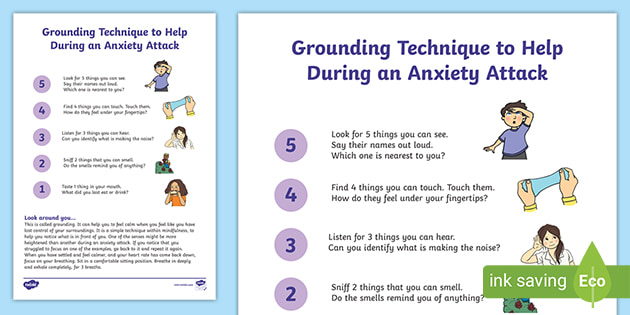

Together with your child, master the deep breathing technique . Sit next to the child, make yourself comfortable so that your back is even and rests on the back of the chair. While counting to five to yourself, inhale, hold your breath for two counts, then exhale slowly, also counting to five. Repeating this exercise will help you relax as much as possible. Formula "1+3+10". Tell your child the following: “As soon as you feel yourself getting angry, do three things. up to 10. Thus, it turns out 1 + 3 + 10. This will help you calm down and regain composure.

Repeating this exercise will help you relax as much as possible. Formula "1+3+10". Tell your child the following: “As soon as you feel yourself getting angry, do three things. up to 10. Thus, it turns out 1 + 3 + 10. This will help you calm down and regain composure.

Unfortunately, it happens that old habits do not disappear. As a good parent, you cannot allow this anger and irritation to continue. Try to apply "penalties" (they must be age and deed appropriate) and make a contract with the child. "If you start again... you'll have to stand in the corner for five minutes."

And be consistent!

Step by step change plan for problem child behavior

Adult behavior is a good example for a child. Therefore, you need to start re-education by looking from the outside at your own ways of expressing anger. Here are some questions to help you. How did your parents deal with anger? How do you usually deal with anger? Does it work in your case? Are you a good example of managing your condition for your child? What about the rest of your family? What lessons can a child learn from these actions? How do you usually respond to your child's anger? Does it work? What would you like to change? Write down your thoughts and then make a plan to change it.

1. Analyze how well your child can control his emotions. The way our children act often speaks to the deeper causes of the problem. Here are some signs that your child needs more intense anger management efforts. Which of these characteristics would apply to your child?

Signs of irascibility

• inability to express feelings when angry.

• frequent outbursts of anger, even over small things.

• Difficulty bringing yourself back to normal when angry.

• development of anger into an attack (for example, with shouting, beating, swearing, etc.).

• Difficulty getting out of a frustrating situation.

• Frequent fights or beatings with other people.

• isolation and silence, lack of inclination to share experiences.

• a tendency to tell, describe, or draw scenes of violence or violent acts.

2. Try to observe the child's temper tantrums for a week. Keep a schedule of your anger on a calendar. Perhaps this will help you find out the causes of these seizures. What can you do to reduce their frequency? Write down your thoughts.

Perhaps this will help you find out the causes of these seizures. What can you do to reduce their frequency? Write down your thoughts.

3. Note how the child behaves before the onset of a fit of anger. Write down your observations and then share them with your child to help him recognize signs of impending anger.

4. What are the likely sources of your child's anger? List them. What can be eliminated? What can be corrected? Plan a strategy to help your child deal with inevitable sources of anger.

5. Does your child have enough vocabulary to express his feelings? If not, consider how you can expand it.

6. Select an anger management strategy to be taught. Set days and times when you will use it, and keep using it until the child can do it without your help.

7. Unhealthy responses must be combated.

8. What punishments are you going to use to save him from misbehaving.

Anger is a completely natural emotion, but when it becomes a habit and begins to negatively affect the child's relationship with the family, with others, or when you notice sudden mood swings that are not associated with an illness, take action.

Behavior modification is hard, painstaking work that must be done consistently and based on reinforcing results through parental encouragement. Your child's progress towards change can be slow, but be sure to celebrate and reward each step along the way. It will take less than 21 days for the first results to appear, so do not rush to give up. Remember that if one approach doesn't work, another will. Record weekly progress in your child's behavior using the template below. Record progress daily in a step-by-step change diary for your child's problem behavior.

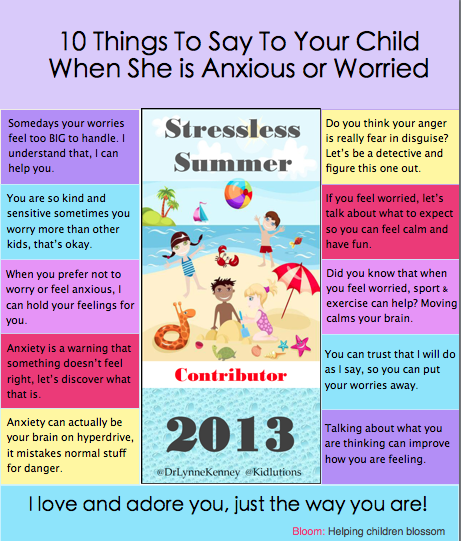

Helping Your Child Manage Anxiety - Child Development

Anxiety can come on suddenly in children of any age. Most often, it occurs in situations where the child is afraid of pain or that the parents will leave him alone. Doctor visits, situations where you bring your child to school, or any change in your child's daily routine can cause anxiety. Despite all the parents' attempts to prepare the child for a new situation, he can still experience anxiety, sometimes very strong.

Doctor visits, situations where you bring your child to school, or any change in your child's daily routine can cause anxiety. Despite all the parents' attempts to prepare the child for a new situation, he can still experience anxiety, sometimes very strong.

Anxiety can manifest itself in children in different ways, but there are typical symptoms: the child has decreased activity, sweaty palms, weakness in the legs, headache or stomach pain. The child may start crying, biting his nails, or shaking his head. Regardless of what caused your child to be so anxious, there are ways to help him overcome his anxiety and prevent it from happening in the future.

First, you need to teach the child to notice the symptoms of anxiety. Gently inform your child when you see changes in his behavior, ask if he sees them too or not. For example, when a child is biting his nails in a stressful situation, tell him: “I see you biting your nails. Do you notice it?" By calmly pointing out your child's behavior, you draw his attention to the symptoms of stress. At the same time, it is important to talk calmly with the child, not to make comments, so as not to cause him a sense of shame, which can increase anxiety.

At the same time, it is important to talk calmly with the child, not to make comments, so as not to cause him a sense of shame, which can increase anxiety.

Second, help your child understand that it is normal to feel anxious and that everyone experiences these symptoms in stressful situations. Clearly explain to your child how uncomfortable situations can cause stress and anxiety, which in turn can lead to headaches or inappropriate behavior. Explain that each person experiences anxiety differently. For example, you could talk about it like this: “I don't like talking to strangers. Sometimes when I have to do this, I get nervous, and then my palms sweat." Help your child understand that it is normal to feel anxious. After all, this is how the body tells us that it is uncomfortable.

When you teach your child to accept feelings of anxiety and recognize its symptoms, teach him to relax. First of all, find out the causes of anxiety in the child and try to calm him down. For example, sitting in line at the hospital, a child may be afraid that the doctor will give him an injection. Talking to your child about what is bothering him will not only clarify the cause of the anxiety, but also help to partially dispel the fear. If anxiety symptoms persist, use stress relief techniques such as breathing exercises, visualization techniques. You can just cheer up the child - this will also give a positive result.

Talking to your child about what is bothering him will not only clarify the cause of the anxiety, but also help to partially dispel the fear. If anxiety symptoms persist, use stress relief techniques such as breathing exercises, visualization techniques. You can just cheer up the child - this will also give a positive result.

If all this fails, the stressors should be eliminated. If your child has temper tantrums or panic attacks, take them to a place where they feel safe. Don't force your child to do things that make them anxious. If your child is afraid of heights, don't force him to ride the Ferris wheel. If he's afraid of life-size puppets, don't ask him to take a photo with a life-size puppet at the entertainment center. Otherwise, the child will not only not get rid of anxiety, but in addition will also feel resentment towards the parents who subjected him to such stress. It’s better to just gently encourage the child, and over time, he will gradually learn to cope with anxiety.