How to help a child cope with death

When a Loved One Dies: How to Help Your Child (for Parents)

When a loved one dies, children feel and show their grief in different ways. How kids cope with the loss depends on things like their age, how close they felt to the person who died, and the support they receive.

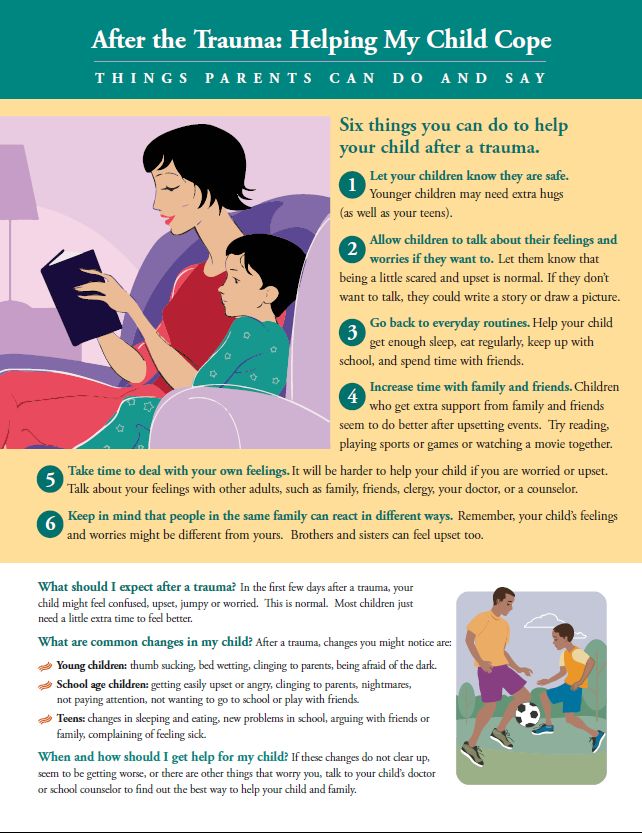

Here are some things parents can do to help a child who has lost a loved one:

Use simple words to talk about death. Be calm and caring when you tell your child that someone has died. Use words that are clear and direct. "I have some sad news to tell you. Grandma died today." Pause to give your child a moment to take in your words.

Listen and comfort. Every child reacts in their own way when they learn that a loved one has died. Some kids cry. Some ask questions. Others seem not to react at all. That's OK. Stay with your child to offer hugs or comfort. Answer your child's questions. Or just be together for a few minutes. It's OK if your child sees your sadness or tears.

Put feelings into words. Ask kids to say what they're thinking and feeling. Label some of your own feelings. This makes it easier for kids to share theirs. Say things like, "I know you're feeling very sad. I'm sad, too. We both loved Grandma so much, and she loved us too."

Tell your child what to expect. If the death of a loved one means changes in your child's life or routine, explain what will happen. This helps your child feel prepared. For example, "Aunt Sara will pick you up from school like Grandma used to." Or, "I need to stay with Grandpa for a few days. That means you and Dad will be home taking care of each other. But I'll talk to you every day, and I'll be back on Sunday."

Explain events that will happen. Allow children to join in rituals like viewings, funerals, or memorial services. Tell them ahead of time what will happen. For example, "Lots of people who loved Grandma will be there. We will sing, pray, and talk about Grandma's life. People might cry and hug. They might say to us, 'I'm sorry for your loss.' We can say, 'Thank you,' or, 'Thanks for coming.' You can stay near me and hold my hand if you want."

People might cry and hug. They might say to us, 'I'm sorry for your loss.' We can say, 'Thank you,' or, 'Thanks for coming.' You can stay near me and hold my hand if you want."

You might need to explain burial or cremation. For example, "After the funeral, there is a burial at a cemetery. The person's body is in a casket (or coffin) that gets buried in the ground with a special ceremony. This can feel like a sad goodbye, and people might cry." Share your family's beliefs about what happens to a person's soul or spirit after death.

Explain what will happen after the service, too. For example, "We all will go eat food together. People will laugh, talk, and hug some more. Talking about happy times with Grandma and being together helps people start to feel better."

Give your child a role. Having a small, active role lets kids feel part of things and helps them cope. You might invite your child to read a poem, pick a song to be played, gather some photos to display, or make something. Let kids decide if they want to take part, and how.

Let kids decide if they want to take part, and how.

Help your child remember the person. In the days and weeks ahead, encourage your child to draw pictures or write down stories of their loved one. Don't avoid talking about the person who died. Sharing happy memories helps heal grief.

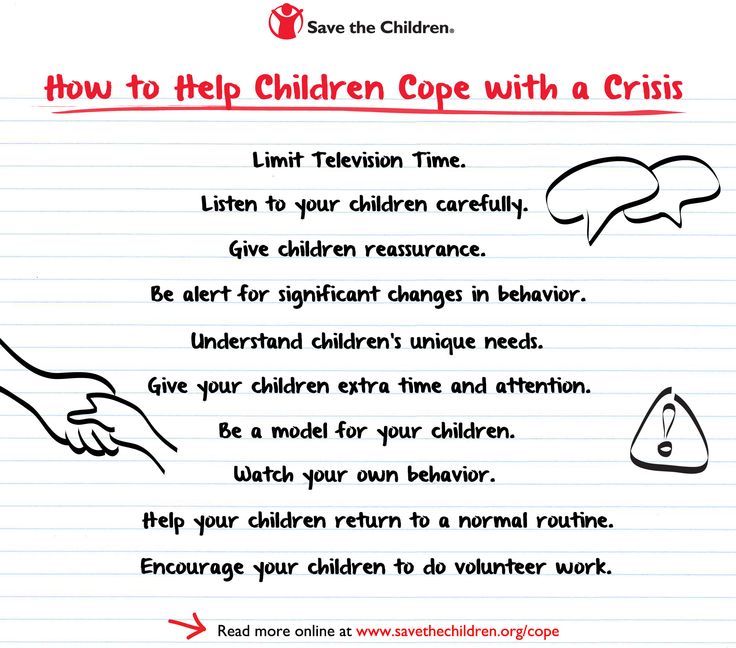

Give comfort and reassure your child. Notice if your child seems sad, worried, or upset in other ways. Ask about feelings and listen. Let your child know that it takes time to feel better after a loved one dies. Some kids may have trouble sleeping or have fears or worries. Let kids know these things will get better. Give them extra time and care. Support groups and counseling can help kids who need more support.

Help your child feel better. Provide the comfort your child needs but don't dwell on sad feelings. After a few minutes of talking and listening, shift to an activity or topic that helps your child feel a little better. Play, make art, cook, or go somewhere together.

Give your child time to heal from the loss. Grief is a process that happens over time. Be sure to talk often and listen to see how your child is feeling and doing. Healing doesn't mean forgetting about your loved one. It means remembering the person with love. Loving memories stir good feelings that support us as we go on to enjoy life.

Get more help if needed. If a loved one's death was sudden, deeply stressful, or violent, a child may need therapy to help them heal. If your child's distress lasts for more than a few weeks, or if you think your family needs more help, talk with your child's doctor. They can help you find the right therapist to work with.

Reviewed by: D'Arcy Lyness, PhD

Date reviewed: September 2021

Helping Children Deal With Grief

Most young children are aware of death, even if they don’t understand it. Death is a common theme in cartoons and television, and some of your child’s friends may have already lost a loved one. But experiencing grief firsthand is a different and often confusing process for kids. As a parent, you can’t protect a child from the pain of loss, but you can help him feel safe. And by allowing and encouraging him to express his feelings, you can help him build healthy coping skills that will serve him well in the future.

But experiencing grief firsthand is a different and often confusing process for kids. As a parent, you can’t protect a child from the pain of loss, but you can help him feel safe. And by allowing and encouraging him to express his feelings, you can help him build healthy coping skills that will serve him well in the future.

After losing a loved one, a child may go from crying one minute to playing the next. His changeable moods do not mean that he isn’t sad or that he has finished grieving; children cope differently than adults, and playing can be a defense mechanism to prevent a child from becoming overwhelmed. It is also normal to feel depressed, guilty, anxious, or angry at the person who has died, or at someone else entirely.

Very young children may regress and start wetting the bed again, or slip back into baby talk.

Encourage a child grieving to express feelingsIt’s good for kids to express whatever emotions they are feeling. There are many good children’s books about death, and reading these books together can be a great way to start a conversation with your child. Since many children aren’t able to express their emotions through words, other helpful outlets include drawing pictures, building a scrapbook, looking at photo albums, or telling stories.

There are many good children’s books about death, and reading these books together can be a great way to start a conversation with your child. Since many children aren’t able to express their emotions through words, other helpful outlets include drawing pictures, building a scrapbook, looking at photo albums, or telling stories.

It is hard to know how a child will react to death, or even if he can grasp the concept. Don’t volunteer too much information, as this may be overwhelming. Instead, try to answer his questions. Very young children often don’t realize that death is permanent, and they may think that a dead loved one will come back if they do their chores and eat their vegetables. As psychiatrist Gail Saltz, MD, explains, “Children understand that death is bad, and they don’t like separation, but the concept of ‘forever’ is just not present.”

Older, school-age children understand the permanence of death, but they may still have many questions. Do your best to answer honestly and clearly. It’s okay if you can’t answer everything; being available to your child is what matters.

Do your best to answer honestly and clearly. It’s okay if you can’t answer everything; being available to your child is what matters.

When discussing death, never use euphemisms. Kids are extremely literal, and hearing that a loved one “went to sleep” can be scary. Besides making your child afraid of bedtime, euphemisms interfere with his opportunity to develop healthy coping skills that he will need in the future.

Attending the funeralWhether or not to attend the funeral is a personal decision that depends entirely on you and your child. Funerals can be helpful for providing closure, but some children simply aren’t ready for such an intense experience. Never force a child to attend a funeral. If your child wants to go, make sure that you prepare him for what he will see. Explain that funerals are very sad occasions, and some people will probably be crying. If there will be a casket you should prepare him for that, too.

Keep in mind that even the best-prepared child might get upset, and his behavior can be unpredictable. “Kids will not behave in a way that you might want or expect,” Dr. Saltz notes. “If you decide that a funeral is not the best way, there are other ways to have a goodbye.” Planting a tree, sharing stories, or releasing balloons can all be good alternatives for providing closure to a child.

Discussing an afterlifeThe idea of an afterlife can be very helpful to a grieving child, observes Dr. Saltz. If you have religious beliefs about the afterlife, now is the time to share them. But even if you aren’t religious you can still comfort your child with the concept that a person continues to live on in the hearts and minds of others. You can also build a scrapbook or plant something that represents the person you have lost.

Don’t ignore your own griefChildren will often imitate the grieving behavior of their parents. It is important to show your emotions as it reassures children that feeling sad or upset is okay. However, reacting explosively or uncontrollably teaches your child unhealthy ways of dealing with grief.

It is important to show your emotions as it reassures children that feeling sad or upset is okay. However, reacting explosively or uncontrollably teaches your child unhealthy ways of dealing with grief.

Children find great comfort in routines, so if you need some time alone, try to find relatives or friends who can help keep your child’s life as normal as possible Although it is important to grieve over the death of a loved one, it is also important for your child to understand that life does go on.

Some specific situationsFor many children the death of a pet will be their first exposure to death. The bonds that children build with their pets are very strong, and the death of a family pet can be intensely upsetting. Don’t minimize its importance, or immediately replace the dead pet with a new animal. Instead, give your child time to grieve for his dog or cat.This is an opportunity to teach your child about death and how to deal with grieving in a healthy and emotionally supportive way.

The death of a grandparent is also a common experience for young children, and it may bring up many questions, such as, “Will my mom be next?” It is important to tell your child that you will probably live for a long time.

After the death of a parent, children will naturally worry about the death of the remaining parent or other caretakers. Reassure a child that he is loved and will always be cared for. It is a good idea to rely on family members during this time to help provide additional nurturing and care. Dr. Saltz also recommends therapy in the case of a significant death, such as the death of a parent or sibling. “Therapy provides another outlet for talking when a child may feel like he can’t talk with other family members, because they are grieving as well.”

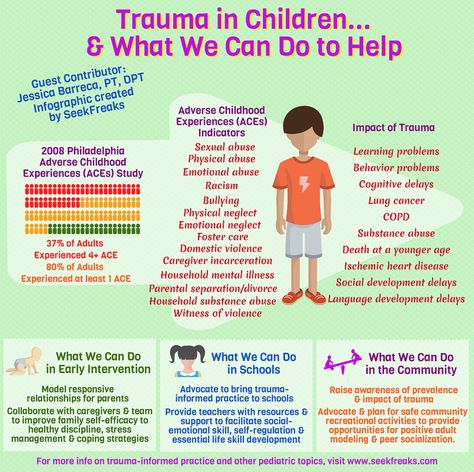

Treating serious problemsIf you notice that your child seems unusually upset and unable to cope with grief and his loss, he may have something called adjustment disorder. Adjustment disorder is a serious and distressing condition that some children develop after experiencing a painful or disruptive event. It is a good idea to consult your child’s doctor if you feel that your child isn’t recovering from a loss in a healthy way.

It is a good idea to consult your child’s doctor if you feel that your child isn’t recovering from a loss in a healthy way.

How to help your child after the death of a parent

The information in this article explains how to help your child after the death of a parent.

back to top of pageUnderstanding a child's grief

For any child, the death of a parent is the hardest test. No matter how old your child is, you may want to protect him from the sadness and confusion that you are experiencing. Children, as well as adults, may need help in dealing with loss and adjusting to life after it. Remember that how a child experiences grief depends on their age, understanding of death, and the behavior of others.

Grief in young children

Young children express their grief differently than adults. After the death of a parent, they may have short and strong emotional outbursts. In addition, they may experience physical reactions, such as pain in the body or changes in sleep patterns. Some children may express grief through changes in their behavior. They may have difficulty completing daily tasks or behave in ways they have never behaved before. They may grieve for short periods of time with breaks in between. For example, a child may cry or appear sad, and shortly thereafter ask to go for a walk or start playing. Other children may not show any signs of sadness or grief.

Some children may express grief through changes in their behavior. They may have difficulty completing daily tasks or behave in ways they have never behaved before. They may grieve for short periods of time with breaks in between. For example, a child may cry or appear sad, and shortly thereafter ask to go for a walk or start playing. Other children may not show any signs of sadness or grief.

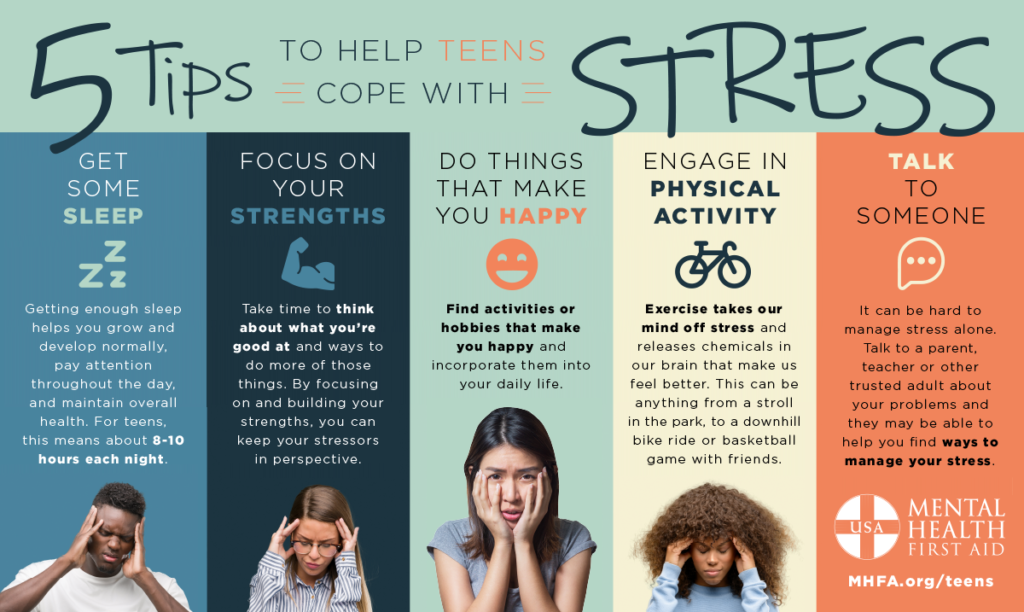

Adolescents experience grief

While younger children may not fully understand death, adolescents have a more mature understanding of it. Adolescents are at a stage in their lives when their personality, way of thinking and emotions are being formed. After the death of a parent, they can experience a wide range of emotions. Some may feel that their place in the family has changed and take on adult responsibilities. Adolescents may need privacy to grieve. Let your child know that they can talk to you and ask for support.

back to top of pageHow to help your child

It may be difficult for you to help your child because you yourself are experiencing loss. If you are having trouble communicating with your child, ask for support and help from a family member, friend, social worker, psychologist, or religious or spiritual guide.

If you are having trouble communicating with your child, ask for support and help from a family member, friend, social worker, psychologist, or religious or spiritual guide.

Here are some ways you can help your child cope with loss.

Share your own thoughts and feelings

It is natural not to cry in front of your child, but expressing your emotions can serve as an example for your child to cope with difficulties. Share your own feelings about the loss of a loved one. By telling your child how you feel, you will help your child express his feelings as well. If your family holds any religious or spiritual beliefs, it may help to mention your faith in the conversation.

Talk about death directly

When talking about death, avoid phrases such as "gone" or "left." This can mislead the child and make them think that their parent will soon wake up or return. Honesty and directness will help your child understand what happened and learn how to deal with grief. Some families use religious or spiritual beliefs to help the child understand that the parent is not physically present. If you think this might be helpful, ask a religious or spiritual guide for help.

Some families use religious or spiritual beliefs to help the child understand that the parent is not physically present. If you think this might be helpful, ask a religious or spiritual guide for help.

Honor the memory of the deceased

Rituals to honor a loved one can have a calming effect on you and your child. By maintaining old family traditions or creating new ones, you and your family can keep in touch with your loved one. In different cultures and religions, there are rituals to honor someone's memory. Some families have their own rituals, such as getting together and preparing a special meal, planting a garden, visiting favorite places, or celebrating birthdays. Whatever you choose, remember that there is no right or wrong way to honor a loved one. Try to do what will be most comfortable for your family.

back to top of pageFuneral participation

Whether your child attends a funeral or a farewell ceremony is a decision between you and your child. The opportunity to be present at the funeral will allow the child to experience grief with his family. If your child is attending a funeral, make sure they know what to expect beforehand. You may also want to consider having your child participate in the ceremony. The child can write a letter or draw something and put it in the coffin. He can also make a collage with photos of the parent for the funeral.

The opportunity to be present at the funeral will allow the child to experience grief with his family. If your child is attending a funeral, make sure they know what to expect beforehand. You may also want to consider having your child participate in the ceremony. The child can write a letter or draw something and put it in the coffin. He can also make a collage with photos of the parent for the funeral.

At the funeral, always remember the child's feelings and check his health. You may want to ask someone your child trusts to occasionally go out with your child for breaks. If the child wants to leave the room, let him do it. After the funeral or farewell ceremony, the child may have new questions about death.

back to top of pageResources for you and your family

MSK resources

Support is available for you and your family, no matter where you are in the world. Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) offers a range of resources for grieving families and their friends. You can learn more about these resources at www.mskcc.org/experience/caregivers-support/support-grieving-family-friends

You can learn more about these resources at www.mskcc.org/experience/caregivers-support/support-grieving-family-friends

Talking with Children About Cancer

Talking about Cancer with Children is a program designed to support parents undergoing cancer treatment in raising their children and adolescents. Our social workers offer family support groups, individual and group counseling, access to resources, and guidance for professionals including school social workers, school psychologists, counselors, teachers, and other staff. For more information, visit www.mskcc.org/experience/patient-support/counseling/talking-with-children

Bereavement Program

646-888-4889

MSK offers services through the Bereavement Program to help bereaved family members and friends. People who have lost a loved one to cancer may find it helpful to talk to other grieving people. The Departments of Social Work, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Sciences offer support groups and educational programs for people who have lost a loved one to cancer. Services include short courses of individual counseling, resources for bereaved children, adult groups, and access to local resources.

Services include short courses of individual counseling, resources for bereaved children, adult groups, and access to local resources.

For more information or to join a bereavement support group, call Social Work at 646-888-4889.

MSK Counseling Center

646-888-0200

Some bereaved families find they have benefited from expert advice. Our psychiatrists and psychologists work at the bereavement clinic, where they provide counseling and support for individuals, couples and families, and can prescribe medications to help manage depression.

Spiritual support

212-639-5982

Our chaplains are ready to listen and support family members, pray, reach out to local clergy or religious groups, simply offer comfort and extend a spiritual helping hand. Any person can apply for spiritual support, regardless of their formal religious affiliation.

Additional resources

Books, educational resources and local support programs are available for bereaved parents and children.

Useful websites

The Dougy Center: national center for children and families in grief

www.dougy.org

The Dougy Center provides support for grieving children, teens, young adults and families. The Center provides online resources and programs to support and assist families in grief.

Red Door Community

212-647-9700

www.reddoorcommunity.org

Provides meeting places for people living with cancer and their family and friends. Enables people to meet each other to build systems of mutual support. Provides free assistance and organizes communication groups, lectures, seminars and social events. The Red Door Community used to be called Gilda's Club.

Useful literature

Books for adults on how to help children and adolescents deal with grief

Guiding Your Child Through Grief

By James P. Emswiler

Emswiler

The Grieving Child: A Parent's Guide

By Helen Fitzgerald

Helping Children Cope with the Loss of a Loved One: A Guide for Grown Ups

By William C. Kroen

How Do We Tell the Children? A Step-by-Step Guide for Helping Children Two to Teen Cope When Someone Dies

By Dan Schaefer and Christine Lyons

Preparing Your Children for Goodbye: A Guidebook for Dying Parents

Author: Lori Hedderman

Take My Hand: Guiding Your Child Through Grief

Author: Sharon Marshall

Talking about Death: A Dialogue between Parent and Child

By Earl A. Grollman

Books for children about death and grief

Always by My Side (Always next to me)

For children aged 4 to 8

Author: Susan Kerner

Everett Anderson's Goodbye

For children aged 5 to 8

Author: Lucille Clifton

Gentle Willow: A Story for Children about Dying

For children aged 4 to 8

By Joyce C. Mills

Mills

The Fall of Freddie the Leaf

For children over 4 years of age

By Leo Buscaglia

The Goodbye Book

For children aged 3 to 6

Author: Todd Parr

Lifetimes: A Beautiful Way to Explain Death to Children

For children aged 5+

Author: Bryan Mellonie

The Memory Box: A Book about Grief

For children aged 4 to 9years

Author: Joanna Rowland

I Miss You: A First Look at Death

For children aged 4 to 8

By Pat Thomas and Leslie Harker

The Next Place (Better world

For children aged 5+

By Warren Hanson

Sad Isn't Bad: A Good-Grief Guidebook for Kids Dealing with Loss

For children aged 6 to 9

Author: Michelene Mundy

Samantha Jane's Missing Smile: A Story About Coping with the Loss of a Parent

For children aged 5 to 8

By Julie Kaplow and Donna Pincus

Saying Goodbye to Daddy

For children aged 4+

Author: Judith Vigna

Tear Soup: A Recipe for Healing After Loss

For children aged 8+

Author: Pat Schwiebert

What on Earth Do You Do When Someone Dies? (What do you do when someone dies?)

For children aged 5 to 10

Author: Trevor Romain

When Dinosaurs Die: A Guide to Understanding Death

For children aged 4 to 7

Posted by Laurie Kransy Brown and Marc Brown

Where Are You? A Child's Book about Loss (Where are you? Children's book about loss)

For children aged 4 to 8

Author: Laura Olivieri

Books for children with tasks for understanding death and dealing with grief

Help Me Say Goodbye: Activities for Helping Kids Cope When a Special Person Dies

For children aged 5 to 8

By Janis Silverman

When Someone Very Special Dies: Children Can Learn to Cope with Grief

For children aged 9 to 12

By Marge Heegaard

14 tips on how to help a child cope with the death of a loved one

When an unpleasant event occurs, we adults often do not know how to react, what to do and how to feel. We are afraid and do not know how to tell the child about what happened. Our blogger, psychologist Larisa Milova, tells how to help children cope with severe shocks.

We are afraid and do not know how to tell the child about what happened. Our blogger, psychologist Larisa Milova, tells how to help children cope with severe shocks.

How to tell your child about death or other serious loss

- divorce;

- father or mother leaving the family;

- moving to another city, which will entail a change in kindergarten or school, a break in relations with friends and familiar surroundings;

- serious illness of a loved one.

Such a request is often heard at consultations. As a rule, adults, when they find themselves in a situation where they need to tell a child about a loss, fall into confusion. They are already experiencing grief and heaviness from suddenly fallen tasks that need to be solved, and then everything needs to be explained to the child. Many people think that it will be better for a child if information is hidden from him. My advice is don't do that. First, remember: did you experience bereavement, the death of loved ones, or the collapse of your family as a child? What did this mean for you? How did you experience this period? Who supported you? How did you deal with these feelings?

How children cope with bereavement

- They experience all the same feelings as adults: fear, grief, sadness, sadness, anger, despair, etc.

myth).

myth). - It is difficult for them to express feelings, it is difficult to explain in words what is happening. He does not yet have the right words and experience (which is why psychologists use the methods of play therapy and art therapy to help children). The younger the child, the more likely it is that he will express his feelings through bodily symptoms, emotional manifestations or behavior.

- Children have a poor idea of what exactly is happening, and do not realize the reasons for what is happening due to their age and experience (which is why children in difficult situations and after may increase anxiety and fear).

- It seems to children that they are to blame for something.

If adults hush up the situation, trying to protect children from experiences, then the following happens:

- The child thinks that adults blame him for what happened. Children may perceive the silence and grief of adults as an accusation.

- If someone just "disappeared", they become afraid that other family members may also disappear.

- In a divorce, a child may think that his parents do not love him.

How to talk to a child about a divorce, I wrote here.

During traumatic experiences, adults play a key role in the child's experience of trauma. Adults should help him survive the grief, support him so that he does not have to cope with the severity of the loss on his own.

What adults should do:

1. Do not isolate children. Let them be present during family conversations about the departed person, death and funerals.

2. Do not hide your tears and emotions in front of children. There is nothing wrong with children seeing the tears of an adult. Explain that it is very sad and painful for you to say goodbye, so you cry.

3. Provide an open environment where children can ask any questions or share feelings. Do not judge them for questions and feelings.

4. If the child is small, you should hold him on your hands, knees, play with him or sit on the floor more often.

5. Tell your child more often that you love him.

6. Stay close to the child if he cries. Don't try to switch him off, let him cry.

7. Children are calmed by talking about an event, so it makes sense to talk to a child about how he feels about death: “What do you know about death? Have you ever seen the dead? What do you think you will see at the funeral? What would you like to know about death? What would you like to say to the deceased, what to ask?”

8. If the child is a preschooler or elementary school student, invite him to draw his fantasies and fears.

9. Describe death in plain language. Try not to use the metaphors "grandfather fell asleep and will not wake up again", "God called him to himself" and the like. Children tend to take everything literally. It is better to say: "Grandfather died, which means he is no longer among us, we will not see him again.