Oral vitamin k dosage

Vitamin K in neonates: how to administer, when and to whom

Review

. 2001;3(1):1-8.

doi: 10.2165/00128072-200103010-00001.

E Autret-Leca 1 , A P Jonville-Béra

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacology, H pital Bretonneau, University François Rabelais, Tours, France. [email protected]

- PMID: 11220402

- DOI: 10.2165/00128072-200103010-00001

Review

E Autret-Leca et al. Paediatr Drugs. 2001.

. 2001;3(1):1-8.

doi: 10.2165/00128072-200103010-00001.

Authors

E Autret-Leca 1 , A P Jonville-Béra

Affiliation

- 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacology, H pital Bretonneau, University François Rabelais, Tours, France. [email protected]

- PMID: 11220402

- DOI: 10.2165/00128072-200103010-00001

Abstract

Vitamin K-dependent factors are lower in neonates than in adults, and these anomalies are more prevalent in preterm neonates and in breast-fed infants. Vitamin K deficiency can account for vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) which occurs in 3 forms--early, classic and late. Vitamin K should be administered to all neonates at birth or immediately afterwards. However, the protocols for administration (route of administration, dosage, number of doses) remain a subject of discussion. Oral administration of a single dose of vitamin K protects against classical and early VKDB, but is less effective than intramuscular (IM) prophylaxis for the prevention of late VKDB. Although an increased risk of solid tumour, associated vitamin K administration, can be definitively excluded, a low potential risk of lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood can not be ruled out. For formula-fed neonates without risk of haemorrhage, a 2 mg oral dose of vitamin K at birth, followed by a second 2 mg oral dose between day 2 and 7, is probably sufficient to prevent VKDB. For infants who are exclusively or nearly exclusively breast-fed, weekly oral administration of 2mg (or 25 microg/day) vitamin K after the initial 2 oral doses is justified at completion of breast-feeding.

Vitamin K deficiency can account for vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) which occurs in 3 forms--early, classic and late. Vitamin K should be administered to all neonates at birth or immediately afterwards. However, the protocols for administration (route of administration, dosage, number of doses) remain a subject of discussion. Oral administration of a single dose of vitamin K protects against classical and early VKDB, but is less effective than intramuscular (IM) prophylaxis for the prevention of late VKDB. Although an increased risk of solid tumour, associated vitamin K administration, can be definitively excluded, a low potential risk of lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood can not be ruled out. For formula-fed neonates without risk of haemorrhage, a 2 mg oral dose of vitamin K at birth, followed by a second 2 mg oral dose between day 2 and 7, is probably sufficient to prevent VKDB. For infants who are exclusively or nearly exclusively breast-fed, weekly oral administration of 2mg (or 25 microg/day) vitamin K after the initial 2 oral doses is justified at completion of breast-feeding. For neonates at high risk of haemorrhage (premature, neonatal disease, birth asphyxia, difficult delivery, any illness which will delay feeding, known hepatic disease, maternal drugs inhibiting vitamin K activity), the first dose must be administered by the IM or slow intravenous route. Doses should be repeated, particularly in premature infants, by a route of administration decided for each dose according to the clinical state of the infant. For infants of mothers treated with drugs inhibiting vitamin K activity, antenatal maternal prophylaxis (10 to 20 mg/day orally for 15 to 30 days before delivery) prevents early VKDB. After neonatal prophylaxis, as for infants at high risk of haemorrhage, doses need to be repeated at a rate and route of administration decided for each dose, according to the clotting factor profile specific for each infant.

For neonates at high risk of haemorrhage (premature, neonatal disease, birth asphyxia, difficult delivery, any illness which will delay feeding, known hepatic disease, maternal drugs inhibiting vitamin K activity), the first dose must be administered by the IM or slow intravenous route. Doses should be repeated, particularly in premature infants, by a route of administration decided for each dose according to the clinical state of the infant. For infants of mothers treated with drugs inhibiting vitamin K activity, antenatal maternal prophylaxis (10 to 20 mg/day orally for 15 to 30 days before delivery) prevents early VKDB. After neonatal prophylaxis, as for infants at high risk of haemorrhage, doses need to be repeated at a rate and route of administration decided for each dose, according to the clotting factor profile specific for each infant.

Similar articles

-

Prophylactic vitamin K for the prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding in preterm neonates.

Ardell S, Offringa M, Ovelman C, Soll R. Ardell S, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Feb 5;2(2):CD008342. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008342.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018. PMID: 29401369 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Vitamin K, an update for the paediatrician.

Van Winckel M, De Bruyne R, Van De Velde S, Van Biervliet S. Van Winckel M, et al. Eur J Pediatr. 2009 Feb;168(2):127-34. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0856-1. Epub 2008 Nov 4. Eur J Pediatr. 2009. PMID: 18982351 Review.

-

Vitamin K prophylaxis for prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding: a systematic review.

Sankar MJ, Chandrasekaran A, Kumar P, Thukral A, Agarwal R, Paul VK. Sankar MJ, et al. J Perinatol.

2016 May;36 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S29-35. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.30. J Perinatol. 2016. PMID: 27109090 Free PMC article. Review.

2016 May;36 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S29-35. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.30. J Perinatol. 2016. PMID: 27109090 Free PMC article. Review. -

Vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in early infancy.

Shearer MJ. Shearer MJ. Blood Rev. 2009 Mar;23(2):49-59. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2008.06.001. Epub 2008 Sep 19. Blood Rev. 2009. PMID: 18804903 Review.

-

Vitamin K deficiency bleeding in infants and children.

Sutor AH. Sutor AH. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1995;21(3):317-29. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000653. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1995. PMID: 8588159 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Anticonvulsants and the risk of perinatal bleeding complications: A pregnancy cohort study.

Panchaud A, Cohen JM, Patorno E, Huybrechts KF, Desai RJ, Gray KJ, Mogun H, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT. Panchaud A, et al. Neurology. 2018 Aug 7;91(6):e533-e542. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005944. Epub 2018 Jul 6. Neurology. 2018. PMID: 29980637 Free PMC article.

-

Vitamin K deficiency: a case report and review of current guidelines.

Marchili MR, Santoro E, Marchesi A, Bianchi S, Rotondi Aufiero L, Villani A. Marchili MR, et al. Ital J Pediatr. 2018 Mar 14;44(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0474-0. Ital J Pediatr. 2018. PMID: 29540231 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy and hemorrhagic disease of the newborn: an update.

Kazmin A, Wong RC, Sermer M, Koren G.

Kazmin A, et al. Can Fam Physician. 2010 Dec;56(12):1291-2. Can Fam Physician. 2010. PMID: 21156891 Free PMC article.

Kazmin A, et al. Can Fam Physician. 2010 Dec;56(12):1291-2. Can Fam Physician. 2010. PMID: 21156891 Free PMC article. -

Vitamin K in neonates: facts and myths.

Lippi G, Franchini M. Lippi G, et al. Blood Transfus. 2011 Jan;9(1):4-9. doi: 10.2450/2010.0034-10. Epub 2010 Sep 13. Blood Transfus. 2011. PMID: 21084009 Free PMC article. Review. No abstract available.

-

Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program confirms low incidence of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn in Canada.

McMillan DD, Grenier D, Medaglia A. McMillan DD, et al. Paediatr Child Health. 2004 Apr;9(4):235-8. doi: 10.1093/pch/9.4.235. Paediatr Child Health. 2004. PMID: 19655015 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

References

-

- Obstet Gynecol.

1990 Mar;75(3 Pt 1):334-7 - PubMed

1990 Mar;75(3 Pt 1):334-7 - PubMed

- Obstet Gynecol.

-

- BMJ. 1994 Apr 2;308(6933):894-5 - PubMed

-

- Lancet. 1996 Nov 23;348(9039):1456 - PubMed

-

- Thromb Haemost. 1999 Mar;81(3):456-61 - PubMed

-

- Drug Saf.

1999 Jul;21(1):1-6 - PubMed

1999 Jul;21(1):1-6 - PubMed

- Drug Saf.

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Oral Vitamin K Regimen for Newborns

Welcome to the Evidence Based Birth® Q & A Video on Oral Vitamin K

Today’s video is all about evidence on oral Vitamin K regimens. You can read our disclaimer and terms of use.

In this video, you will learn:

- The main reason why oral Vitamin K might not be as effective as the shot

- The most effective oral Vitamin K regimen

- Reasons why some countries don’t use oral Vitamin K

Click Here to get your Free Video Series and Handout!

Links and resources:

- Learn more by reading the Evidence Based Birth® Signature article on Vitamin K

- References

- von Kries, R.

, A. Hachmeister, et al. (1995). “Repeated oral vitamin K prophylaxis in West Germany: acceptance and efficacy.” BMJ310(6987): 1097-1098.

, A. Hachmeister, et al. (1995). “Repeated oral vitamin K prophylaxis in West Germany: acceptance and efficacy.” BMJ310(6987): 1097-1098. - van Hasselt, P. M., T. J. de Koning, et al. (2008). “Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding in breastfed infants: lessons from the Dutch and Danish biliary atresia registries.” Pediatrics121(4): e857-863.

- von Kries, R.

Enjoy the video, and I hope you find it helpful! Stay tuned for our next Q & A!

Want to submit a question for consideration?

Submit your question for the Q & A

Transcript

Hi, everyone. In today’s video we’re going to take a look at the evidence for using oral vitamin K drops in newborns instead of the vitamin K shot.

Hi, everyone. I’m so excited to see you again. Thanks for taking the time to watch this video and thanks for all your comments on the other videos. I can’t tell you how excited everyone is to have the opportunity to learn more about vitamin K and eye ointment.

My name is Rebecca Dekker, and I’m a nurse with my PhD. I’m the founder of Evidence Based Birth®. I originally created these videos in 2014 to celebrate the release of my continuing education course all about vitamin K and eye ointment so everybody could get something out of the release of the course, even if you weren’t enrolled. I updated these videos in 2017.

Back in 2014 when I filmed these videos for the first time, I asked everyone what they wanted me to teach about this in this video lesson, and I got quite a few responses. It seemed like the most popular request by far was for me to teach about the use of oral vitamin K drops instead of the vitamin K shot. Let’s get started.

Now if you didn’t watch my first video lesson on vitamin K or you’ve never read my blog article before about vitamin K, you might want to do that first so you have a basic understanding of why vitamin K levels are important in newborns.

Just as a reminder, babies are born with limited amounts of vitamin K, and they don’t get very much through breast milk. If they don’t have enough vitamin K, they can start bleeding suddenly, any time in the first six months of life. This type of bleeding is rare, but when it does happen, it can be dangerous because the bleeding often happens in the brain.

Now when I released my blog article in 2014 about vitamin K, a lot of people asked me, if a parent decides to do the oral vitamin K instead of giving their baby the shot, what’s the best regimen to prevent bleeding? Let’s talk about the answer to that question.

Research on oral vitamin K drops originally started by looking at a three-dose regimen. This meant that the baby would get one milligram of oral vitamin K at birth, by mouth, once again again about a week later, and then once more between four and six months of age. Research is very clear that although this three-dose regimen does lower the risk of the baby bleeding from vitamin K deficiency, it’s not as good as the shot.

However, the question comes up, are there any other regimens that are helpful? What about weekly or daily administration of oral vitamin K? There is one really interesting study that compares the weekly and daily regimen. Based on that study, the most promising oral regimen seems to be giving a weekly dose of oral vitamin K for the first six months of life.

Here’s the deal. The main concern that doctors have with using oral vitamin K instead of the shot is that oral vitamin K probably won’t work for babies with undiagnosed gallbladder problems. Gallbladder problems in babies are rare. They happen in about one out of 60,000 infants, but they’re serious because they often start with bleeding in the brain. Babies with gallbladder problems have trouble absorbing fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin K in their stomach. That’s why they are at higher risk for vitamin K deficiency bleeding.

The good thing about giving vitamin K by mouth weekly instead of just three times during infancy is that the weekly dose seems to protect these babies with undiagnosed gallbladder disease. This regimen used to be used in Denmark. What they did is that all babies got two milligrams of oral vitamin K after birth and then one milligram orally weekly as long as the babies were getting at least half of their feedings through breast milk.

What they did in Denmark is they tracked all of the babies that had gallbladder problems during that time. During this about six-year period, there were 23 babies that had that rare gallbladder problem. Out of those 23 babies, only one of them had a case of vitamin K deficiency bleeding, but it was not in the brain. None of these babies had bleeding in the brain, which showed that the oral weekly dose did protect these babies with the gallbladder problems.

When they compared this regimen to the shot, it was just as effective as the shot. Another way of saying it would be to say that the shot was also very effective at preventing brain bleeds in babies with that rare, undiagnosed gallbladder problem.

Now one of the interesting things about this research is that in Denmark they actually stopped using the weekly vitamin K oral dose and now they only use the vitamin K shot. The main reason that they stopped using the oral vitamin K is because it’s no longer available on the market. You’ll find that, around the world, whether or not countries can offer the oral regimen depends on whether it’s available for purchase in their country.

What if you’re a parent in the United States and you want to use this weekly oral regimen? One of the problems is that we don’t have a licensed or FDA-approved version of oral vitamin K for infants. This is called K-Quinone; it is a form of oral vitamin K that you used to be able to buy at food health stores, but I don’t think you can purchase it anymore. There’s at least one other option I’ve seen for sale online in the United States.

One of the problems with these oral vitamin K options is that they’re not regulated by any third party, so we don’t know if the dosing is accurate. The amount of vitamin K in each drop could vary widely from bottle to bottle because there’s no third party that’s testing it to ensure that the dose is accurate.

There’s also a five-milligram vitamin K prescription pill that people sometimes cut up into pieces and then crush and mix with water, and put into the baby’s cheek. But because that pill is five milligrams and you need a one or two-milligram dose, it can be an inaccurate way to get your baby the vitamin K orally.

If parents choose the weekly dose of oral vitamin K, it’s important to remember that when this fat-soluble vitamin is given on an empty stomach, it might not be absorbed as well as vitamin K that’s mixed into formula. If parents are breastfeeding and giving their baby oral vitamin K, it’s important that they give it with a feeding and that they make sure that the baby doesn’t spit it up afterwards.

Before I close, I wanted to mention that one of the strange things about how our minds work is that different people can make completely different decisions based on the same information. One pretty could be given all of the research evidence on vitamin K, what it’s used for, what we know about it, what the different regimens are, how effective they are. Another parent could be given the exact same information, and these two parents could make completely different decisions.

If you want to learn more about this, I recommend a really awesome book called Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What’s Right For You by Dr. Jerome Groopman and Pamela Hartzband. Also, one of the problems about vitamin K is that despite my best attempts to put accurate information out there, there are still so many myths and so many rumors out there online about vitamin K. Just about every week somebody emails me a blog article or a new link that is just filled with bad information about vitamin K. It really makes my head hurt. I can’t even bare to read those articles anymore.

Just a tip: If anything uses really inflammatory language about vitamin K, talks about the dark side of vitamin K or the toxins of vitamin K, those people already made up their minds a long time ago about any kind of shot given to newborns, and they’re not really interested in reporting the facts about vitamin K.

If you’re a birth professional, I wanted to ask you, in the midst of all of this information and misinformation, how are you supposed to be able to help parents tell myths from facts? How would you feel if your words led someone down a path and they made a decision based on inaccurate information? Now imagine the opposite. Imagine you’re in a position where you can give accurate information the other people about controversial topics so that, no matter what decision they make, they’re making a truly informed decision and one that’s not based on your own biases or on rumors or misinformation.

Imagine you’re in a position where you can give accurate information the other people about controversial topics so that, no matter what decision they make, they’re making a truly informed decision and one that’s not based on your own biases or on rumors or misinformation.

I’ve seen this need. It really is a pain point. People don’t want to make decisions based on bad information or to give bad information to their clients. I have literally spent years collecting all of the research that I could find on both vitamin K and eye ointment, and putting them into one intensive online course all about these newborn procedures.

If you take this course, it will completely change how you talk with other people about vitamin K and eye ointment because it will open your eyes to the difference between the many myths out there and what the research evidence shows. The course is good for nursing contact hours and pharmacology CEUs for nurse midwives. I’ve also applied for credits for physicians as well.

If you’ve subscribe to this video series and you’re getting my email reminders about these video lessons, I just wanted to give you a heads up that in my next video I’m going to have an offer for you to enroll in this in-depth class. You’re going to want to open that email if you want to take your learning to the next level. If you’re not subscribed to the emails about this free video series, make sure you subscribe by clicking the link below so that you can find out how to join the class.

I hope you’ve found these videos helpful. My call to action for you today is to leave a comment about the information you’ve learned about oral vitamin K that we covered in this video. Finally, if you haven’t subscribed to the EBB newsletter, which is free, make sure you become a subscriber today, because there are a ton of free printable handouts that you’ll get instant access to and that you can print and share with anyone you like. Thanks for listening. Bye.

Vitamin K: The Complete Guide to Vitamin K

Contents:

➦ Nutrient Features

➦ Effects of Vitamin K on the Body

➦ Indications for Vitamin K Use

➦ Top 3 Best Vitamin K Supplements 900 causes vitamin K deficiency in the body?

➦ How much vitamin K should I take?

➦ Where is vitamin K found?

➦ Vitamin K in foods

➦ Vitamin K in supplements

➦ Vitamin K antagonists

➦ Side effects of vitamin K

➦ What to look for when choosing vitamin K

➦ Answers to popular questions about vitamin K

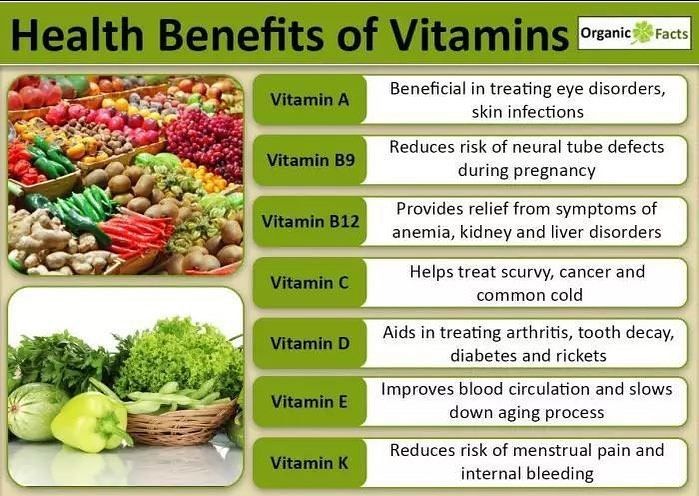

Vitamin K is called a fat-soluble vitamin, one of the 6 most important for proper the functioning of our body. Its most famous function is the regulation of blood clotting, which is why it is called the "clotting vitamin". By the way, the letter K in its name comes from the German word koagulation, which means coagulation.

Its most famous function is the regulation of blood clotting, which is why it is called the "clotting vitamin". By the way, the letter K in its name comes from the German word koagulation, which means coagulation.

Nutrient Features

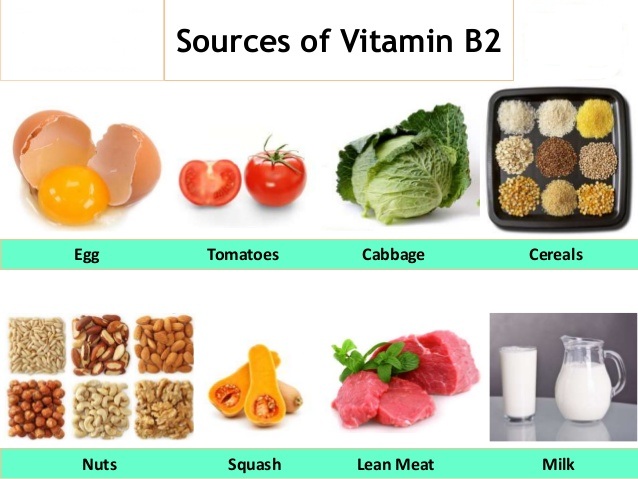

Vitamin K exists in two forms:

➦ Phylloquinone or vitamin K1 - found in plant foods, mainly in green leafy vegetables.

➦ Menaquinone or vitamin K2 - synthesized from phylloquinone by the intestinal microflora of humans, animals and birds that eat herbs and cereals, therefore it is present in animal products.

➦ Menadione or vitamin K3 is a synthetic vitamin, an artificial analogue of natural representatives of the group of compounds with K-vitamin activity.

Vitamin K has several natural forms (vitamers), the most studied of which are MK-4, 5, 6, 7 and 13. In general, they are similar in their action and differ in the activity of absorption in the intestine.

The effect of vitamin K on the body

Vitamin K ensures that platelets stick together and form a blood clot, which becomes a natural physical barrier to loss of the body's life force, thus playing a key role in blood clotting. Failures in this mechanism can be potentially life-threatening.

Failures in this mechanism can be potentially life-threatening.

It was thanks to this property that the micronutrient was discovered by the Danish scientist Henrik Dam. In 1923, he observed chickens receiving food poor in cholesterol. Several weeks of such nutrition led to multiple hemorrhages in the muscles and other tissues of birds, and during the experiments a substance was found that affects blood clotting.

The second important function of vitamin K is participation in the mineralization of bone tissue, in particular, in the fixation of calcium on the bones. Providing the synthesis of bone tissue protein, on which calcium crystallizes, vitamin K is involved in the formation and restoration of bones.

The biological role of vitamin K in the body:

- improves the strength of the walls of blood vessels, reducing the risk of blood loss in injuries

- increases endurance to aerobic exercise and stimulates energy production

- normalizes the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract and muscle function

- 9 900 kidneys

- has an anti-inflammatory effect

- participates in the synthesis of sphingolipids, which are part of the membranes of nerve cells and sheaths of nerve fibers

- increases insulin production

- exhibits immunomodulatory properties

- protects cells from oxidative damage

Indications for use of vitamin K

Given its important role in blood clotting, it is often prescribed during pregnancy to prevent uterine bleeding. With the ability to increase insulin resistance, this nutrient should be included in the diet of people with diabetes. Due to its anti-inflammatory action, it suppresses the development of rheumatoid arthritis and improves the condition of the joints, therefore it is important for the elderly.

With the ability to increase insulin resistance, this nutrient should be included in the diet of people with diabetes. Due to its anti-inflammatory action, it suppresses the development of rheumatoid arthritis and improves the condition of the joints, therefore it is important for the elderly.

In case of reduced blood clotting caused by hypovitaminosis or beriberi K, this vitamin can be prescribed in the form of drops, tablets and injections. For example, an indication for the use of Kanavit is the prevention and treatment of bleeding due to clotting disorders, to inhibit blood clotting factors of various etiologies.

Vitamin K helps maintain the health of blood vessels and the heart, as it prevents the deposition of calcium in the vascular walls and on atherosclerotic plaques. By preventing mineralization of the arteries, it reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, and heart attack. In a Dutch observational study of 564 postmenopausal women, dietary intake of menaquinone was inversely associated with coronary calcification.

Taking part in the formation of the bone protein osteocalcin, vitamin K intake is important in fractures. It delays the onset of osteoporosis, so it is essential for menopausal women. These data were obtained in 2006 from a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of vitamin K supplementation on bone mineral density and fracture. Most of the trials have been conducted in Japan with postmenopausal women. 12 out of 13 trials found that phytonadione or MK-4 supplementation improved bone mineral density. Today, forms of vitamin K are used as a general therapeutic agent for the treatment of osteoporosis in Japan and other countries.

One study showed a beneficial effect of this nutrient on cognitive function: healthy people over 70 years of age with the highest blood levels of vitamin K1 showed the highest verbal performance of episodic memory.

Menaquinone-7 prevents tissue calcification, positively affecting the elasticity and firmness of the skin, slowing down the appearance of wrinkles and ptosis. By participating in redox and metabolic processes, it improves cellular respiration, providing a young and healthy appearance of the skin.

By participating in redox and metabolic processes, it improves cellular respiration, providing a young and healthy appearance of the skin.

A number of clinical studies have shown that taking vitamin K prevents the formation of cancer cells and even promotes their self-destruction, reducing the risk of developing cancer.

In collaboration with the Institute for Cardiovascular Research in Maastricht (Netherlands), from March 12 to April 11, 2020, British scientists have established a link between vitamin K deficiency and the development of severe forms of coronavirus. This study showed that a significant number of patients with severe forms of Covid-19vitamin K deficiency has been observed. cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, ulcerative colitis and short bowel syndrome

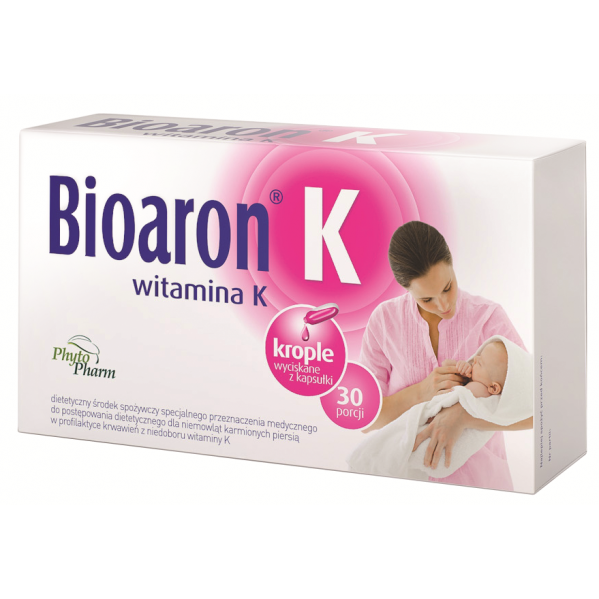

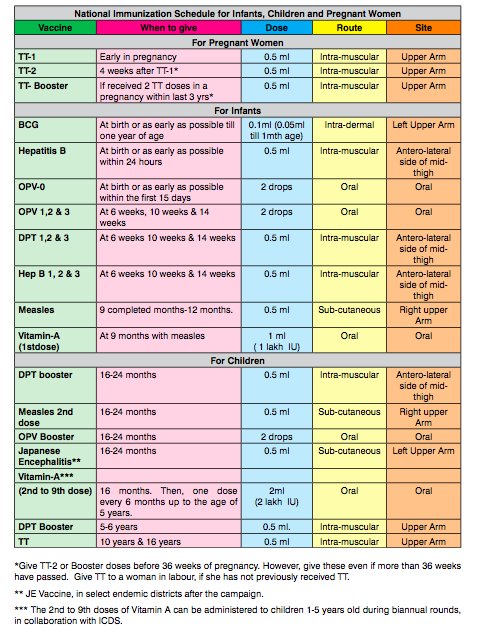

To prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, pediatricians recommend taking 2 mg of vitamin K by mouth at birth and weekly while the baby is breastfeeding.

Top 3 Vitamin K Supplements

What changes does vitamin K deficiency cause in the body?

Prolonged deficiency of vitamin K leads to a decrease in prothrombin activity, causes poor blood clotting and can provoke extensive bleeding, crystallization and blockage of blood vessels.

Because vitamin K is essential for the carboxylation of osteocalcin in bone, a deficiency can affect mineralization, resulting in brittle bones, rheumatoid joint pain, osteoporosis, and other adverse effects.

Low vitamin K levels at birth are a cause of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. In addition, infants cannot produce endogenous synthesis because their intestines are sterile at birth. This is manifested by digestive bleeding, and in severe forms - cerebral bleeding. It is observed only with exclusive breastfeeding.

Other causes of this nutrient deficiency include medications that aim to block coagulation: oral anticoagulants or VKAs. The desired effect is an improvement in blood flow, the main complication is an increased risk of bleeding. The reason for the deficiency may be interaction with antibiotics (cephalosporin), antiepileptic drugs, aspirin, iron.

The desired effect is an improvement in blood flow, the main complication is an increased risk of bleeding. The reason for the deficiency may be interaction with antibiotics (cephalosporin), antiepileptic drugs, aspirin, iron.

There is no real interference between VKA and vitamin K in our diet. However, it is currently recommended that patients taking vitamin K supplements limit their intake of foods rich in this nutrient to one serving per day (particularly kale, spinach, broccoli, avocado) and vary as much as possible. Green tea can be consumed regularly, but in small doses and only once a day.

The classic symptoms of vitamin K deficiency are:

✔ nosebleeds;

✔ hemorrhages;

✔ long-term non-healing skin lesions;

✔ increased fatigue;

✔ osteoporosis;

✔ violation of the digestive tract.

If these signs appear, it is recommended to contact a specialist to undergo an examination for vitamin K levels. If a nutrient deficiency is established, it can be replenished by taking special supplements and vitamin complexes.

How much vitamin K should I take?

Many doctors believe that with a balanced diet, our body can fully satisfy its needs for this nutrient. However, popular Canadian TV and radio health expert Dr. Kate Rem-Blue, in his famous article "Vitamin K2 and the Calcium Paradox", claims that in the modern diet, a person consumes only about 10 percent of vitamin K and "this is completely insufficient to increase the density bones and improved heart health."

Unfortunately, the main dietary myth of the 20th century about the dangers of animal fats for blood vessels led to the fact that vitamin K2 began to be expelled from the diet. Skimmed dairy products were welcomed, the replacement of butter with margarine. Animals and birds were no longer fed with green mass, being transferred to feeds devoid of vitamin K1, from which menaquinones are synthesized. All these are factors that provoke a nutrient deficiency in the body.

Vitamin K is absorbed in the first part of the small intestine through lipid vesicles. The degree of absorption ranges from 20 to 70%. According to studies, in healthy people, the concentration of phylloquinone in fasting plasma ranges from 0.29up to 2.64 nmol/l. However, it is not clear whether this measure can be used to quantify micronutrient status. Individuals with plasma phylloquinone concentrations slightly below the normal range do not show clinical signs of deficiency, possibly because intestinal menaquinones compensate for phylloquinone.

The degree of absorption ranges from 20 to 70%. According to studies, in healthy people, the concentration of phylloquinone in fasting plasma ranges from 0.29up to 2.64 nmol/l. However, it is not clear whether this measure can be used to quantify micronutrient status. Individuals with plasma phylloquinone concentrations slightly below the normal range do not show clinical signs of deficiency, possibly because intestinal menaquinones compensate for phylloquinone.

In most cases, vitamin K status is not routinely assessed, except in individuals who are taking anticoagulants or have bleeding disorders. The only clinically relevant indicator of vitamin K content is prothrombin time (required for blood clotting).

Adequate vitamin K intake values are not well defined and vary by age and sex. The National Health System (NHS) recommends that adults take approximately 0.001 mg of vitamin K per kilogram of body weight daily.

Calculation of the optimal dosage is still being studied, scientists call the figure from 120 micrograms per day for men and 90 micrograms for women to 200 micrograms for healthy adults. It should not be increased during pregnancy or breastfeeding as this is usually provided by a balanced diet. The need for vitamin K increases with high doses of D3 and calcium.

It should not be increased during pregnancy or breastfeeding as this is usually provided by a balanced diet. The need for vitamin K increases with high doses of D3 and calcium.

The table shows the current Adequate Intake (AI) values for vitamin K in micrograms (mcg). For infants, values are based on average intake of the nutrient by healthy infants and the assumption that infants receive a prophylactic dose of vitamin K at birth.

Adequate vitamin K intake

| Age | Men | Women | Pregnancy | Breastfeeding |

| Birth before 6 months | 2.0 mcg | 2.0 mcg | ||

| 7-12 months | 2.5 mcg | 2.5 mcg | ||

| 1-3 years | 30 mcg | 30 mcg | ||

| 4-8 years | 55 mcg | 55 mcg | ||

| 9-13 years old | 60 mcg | 60 mcg | ||

| 14-18 years old | 75 mcg | 75 mcg | 75 mcg | 75 mcg |

| 19+ years | 120 mcg | 90 mcg | 90 mcg | 90 mcg |

US National Health and Nutrition Survey 2011-2012 (NHANES) data show that among children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years, the average daily intake of vitamin K from food is 66 mcg, in adults aged 20 years and older - 122 mcg for women and 138 mcg for men. When considering both foods and supplements, the average daily intake of vitamin K increases to 164 micrograms for women and 182 micrograms for men.

When considering both foods and supplements, the average daily intake of vitamin K increases to 164 micrograms for women and 182 micrograms for men.

Some analyzes of NHANES data from 2003-2006 and 2007-2010 raised concerns about average vitamin K intake, as only one-third of the US population had more than a daily requirement. The importance of these results is not yet entirely clear, as they are only an assessment of the need. Finally, food composition databases provide information mainly on phylloquinone, menaquinones, both dietary and due to bacterial production in the gut, most likely also affect vitamin K status.

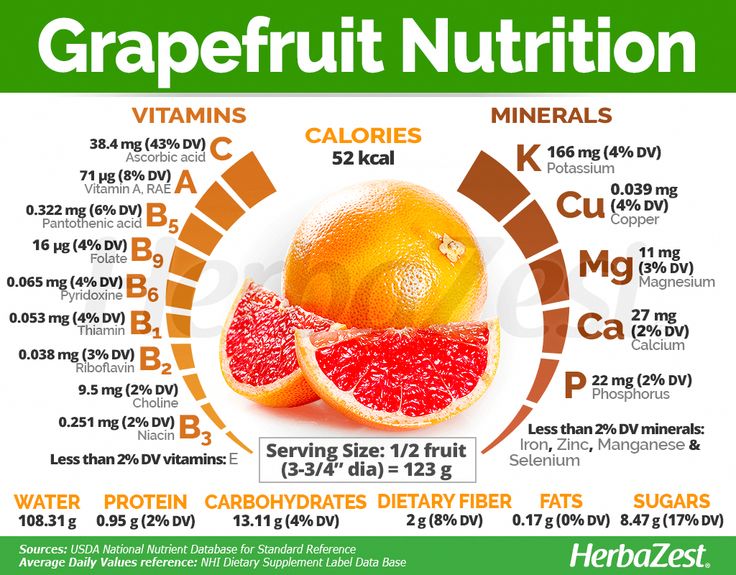

Where is vitamin K found?

Most vitamin K1 in green vegetables (spinach, broccoli, cruciferous vegetables, asparagus, lettuce, parsley, artichokes, beans, leeks, peas, chard and parsnips), as well as carrots and blueberries. Among the record holders for phylloquinones: cabbage, broccoli, lettuce, watercress, spinach, rapeseed and soybean oils, which contain up to 1000 micrograms of vitamin K per 100-gram serving. In green beans, cucumbers, leeks, peas and olive oil - up to 100 mcg. This compound is also found in calf liver, beef or pork, and dairy products.

In green beans, cucumbers, leeks, peas and olive oil - up to 100 mcg. This compound is also found in calf liver, beef or pork, and dairy products.

Vitamin K2 is largely synthesized by intestinal bacteria, but can also be found in certain foods such as fermented foods (cheese, yogurt, milk), liver, fish oil, etc. The content of menaquinone in foods depends on bacterial strains and fermentation conditions. There is a lot of vitamin K2 in natto, a traditional Japanese food made from fermented soybeans. Animals can synthesize MK-4 from menadione, a synthetic form of vitamin K that is sometimes added to poultry and pig feeds.

Data on the bioavailability of various forms of vitamin K from food are very limited. The degree of absorption of phylloquinone in its free form is approximately 80%, but the rate of absorption from food is much lower. Phylloquinone in plant foods is closely related to chloroplasts and is therefore less bioavailable than from oils or supplements. For example, the body absorbs phylloquinone from spinach only 4-17% more than from a tablet. Consumption of vegetables with some fat improves the absorption of phylloquinone, but the amount absorbed is still lower than that of oils. Limited research indicates that long-chain UA may have higher absorption rates than phylloquinone from green vegetables.

Consumption of vegetables with some fat improves the absorption of phylloquinone, but the amount absorbed is still lower than that of oils. Limited research indicates that long-chain UA may have higher absorption rates than phylloquinone from green vegetables.

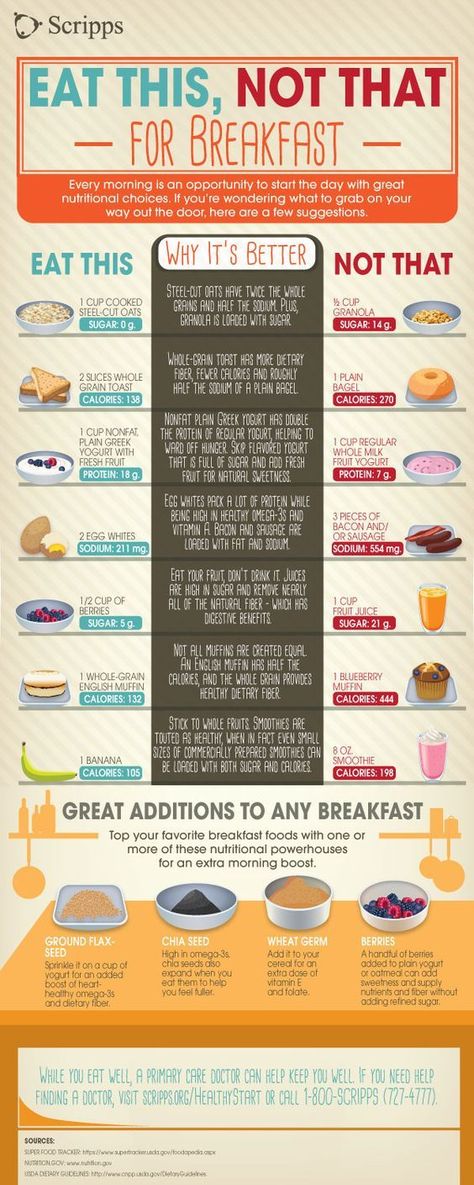

Because vitamin K is fat soluble, vitamin K foods should be consumed in combination with fat to improve absorption. So, drizzle some olive oil or add diced avocado to green leafy lettuce.

An example of a good food combination would also be:

+ broccoli or kale stewed in olive oil

+ roasted Brussels sprouts with almonds

+ addition to salads and other dishes of parsley.

Vitamin K in foods

| Product name | Vitamin K content per 100g | Percentage of daily requirement |

| Parsley (greens) | 1640 mcg | 1367% |

| Watercress (greens) | 542 mcg | 452% |

| Spinach (greens) | 483 mcg | 403% |

| Basil (greens) | 415 mcg | 346% |

| Goose liver | 369 mcg | 307% |

| Leaf lettuce (greens) | 173 mcg | 144% |

| Broccoli | 102 mcg | 85% |

| White cabbage | 76 mcg | 63% |

| Prunes | 59. | 50% |

| Chinese cabbage | 42.9 mcg | 36% |

| Celery (root) | 41 mcg | 34% |

| Cashew | 34.1 mcg | 28% |

| Avocado | 21 mcg | 18% |

| Blueberries | 19.3 mcg | 16% |

| Garnet | 16.4 mcg | 14% |

| Cucumbers | 16.4 mcg | 14% |

| Cauliflower | 16 mcg | 13% |

Vitamin K supplement

This nutrient is present in most multivitamin/multimineral supplements, typically at levels less than 75% of the daily intake. It is also available in dietary supplements containing vitamin K alone or in combination with several other elements, often calcium, magnesium and/or vitamin D.

It is also available in dietary supplements containing vitamin K alone or in combination with several other elements, often calcium, magnesium and/or vitamin D.

These preparations generally have a wider range of vitamin K doses than multivitamin or mineral supplements. , providing 4050 mcg (5063% of DV) or other very high amount. Several forms of the micronutrient are used in dietary supplements, including vitamin K1 in the form of phylloquinone or phytonadione (a synthetic form of vitamin K1) and vitamin K2 in the form of MK-4 or MK-7. There is insufficient data on the relative bioavailability of various forms of supplementation of this vitamin. One study found that both phytonadione and MK-7 supplements are well absorbed, but MK-7 has a longer half-life.

Vitamin K supplements are very common in infants. They compensate for the insufficient intake of the nutrient with breast milk and the non-existent reserves of the newborn. Thus, this supplement limits the risk of hemorrhagic disease in the first months of life.

Dietary supplements containing vitamin K are particularly recommended for the prevention of osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease associated with vascular calcification. The competent authorities recommend not to exceed the dosage of 25 micrograms per day in order to avoid the risk of overdose, the long-term effects of which are not yet known.

Menadione (vitamin K3) is a synthetic form of vitamin K. However, in laboratory studies in the 1980s and 1990s, it was shown to damage liver cells, so it is no longer used in supplements or fortified foods. Indeed, being three times more active than other forms of vitamin K, it can cause significant side effects (nausea, headache, anemia, etc.).

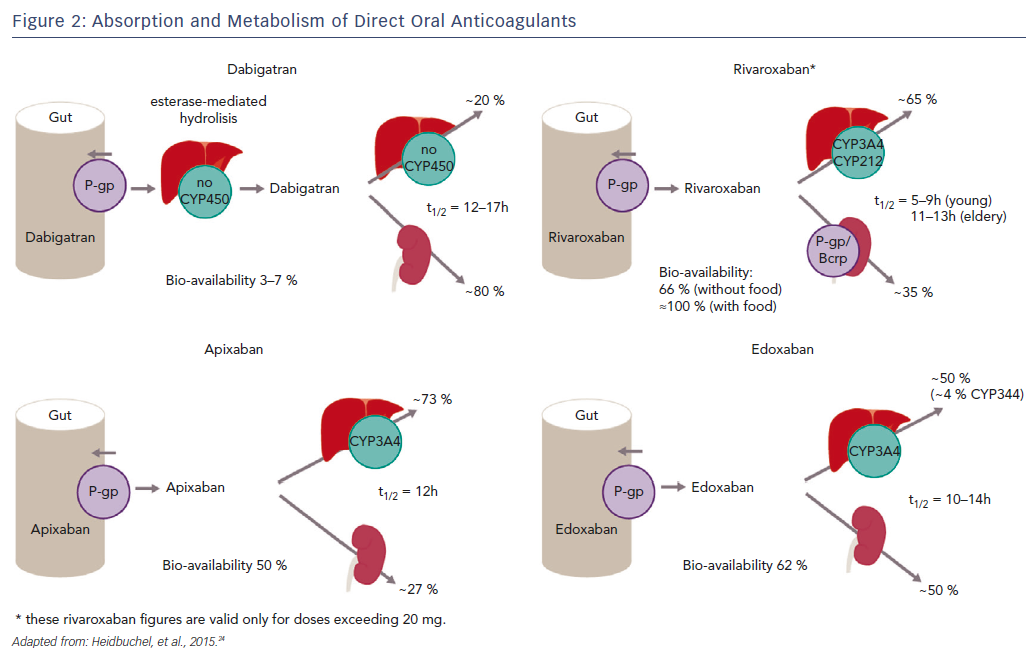

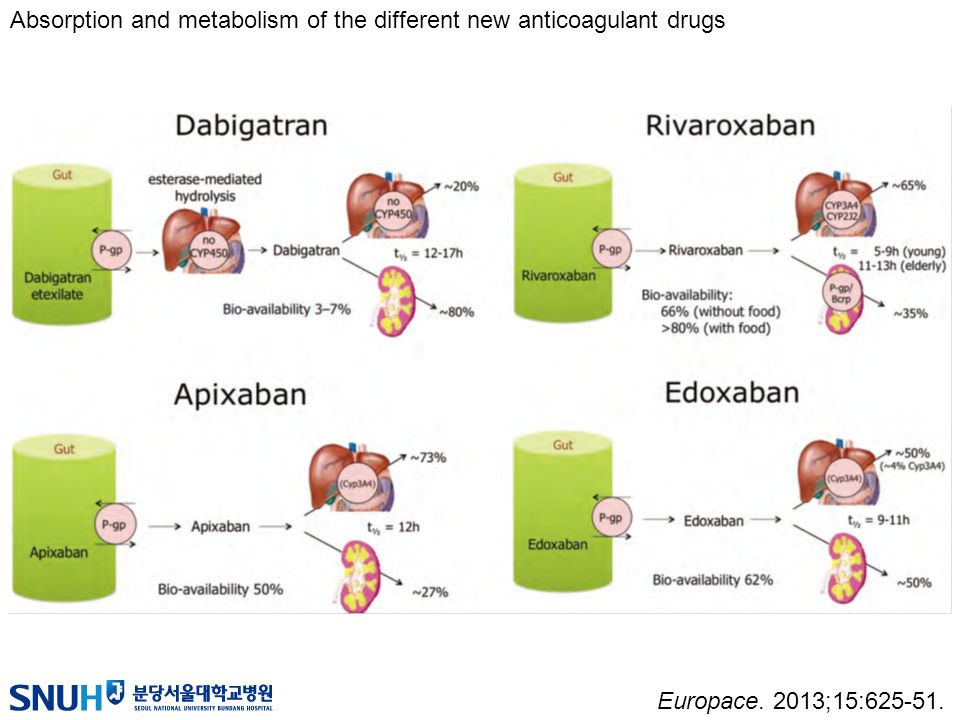

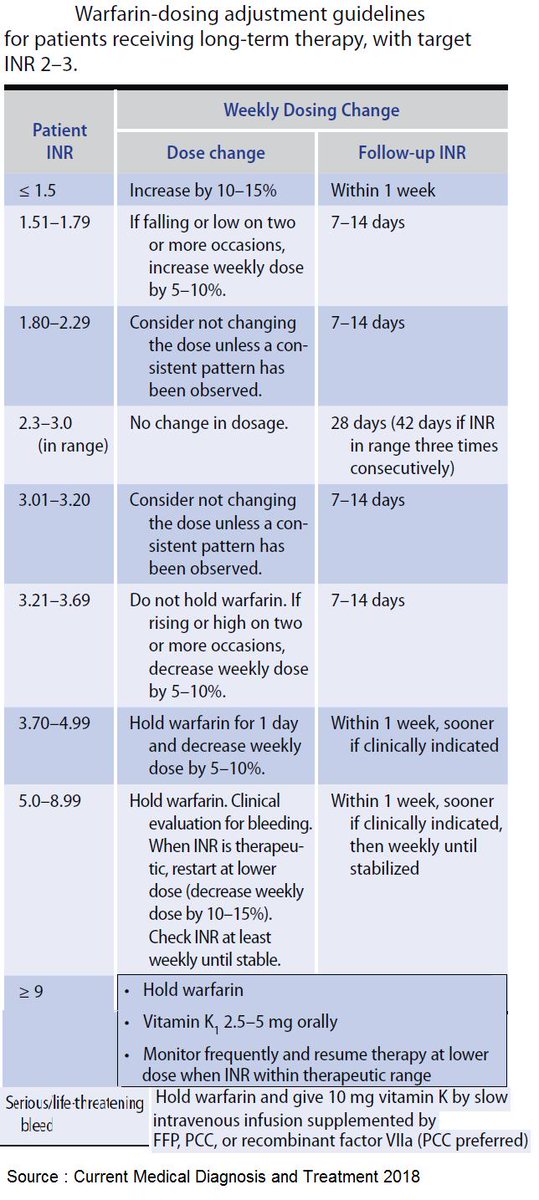

Vitamin K antagonists

Among the substances that weaken the action of vitamin K are the following:

a) derivatives of 4-hydroxycoumarin - neodicoumarin, sincumar, warfarin;

b) indanedione derivative - phenyline.

Anticoagulants, antacids, antibiotics, aspirin, and medicines for cancer, seizures, and high blood pressure can suppress the effects of vitamin K. The compounds that make up these drugs are conditionally antagonists of vitamin K1.

The compounds that make up these drugs are conditionally antagonists of vitamin K1.

Did you know?

Antibiotic medications can destroy vitamin K-producing bacteria in the gut, potentially lowering vitamin K levels, especially if taken for more than a few weeks. People who have a poor appetite with long-term use of antibiotics are at greater risk of deficiency and may benefit from vitamin K supplementation.

In addition, the activity of vitamin K synthesis and its absorption in the intestine are adversely affected by high doses of vitamins A and E.

Side effects of taking vitamin K

Due to its low potential for toxicity, vitamin K has no clear contraindications. No side effects associated with increased intake of vitamin K from food or supplements have been reported in humans or animals.

Common contraindications for vitamin K supplementation in the form of supplements include:

❌ taking anticoagulants, which, unlike menaquinone and phylloquinone, “work” in reverse and promote blood thinning

❌ hereditary hypoprothrombinemia (low level of prothrombin, a blood clotting protein)

❌ kidney failure.

The use of vitamin K also requires caution in newborns and in case of individual intolerance.

There is a case in Ayrshire where a man with an artificial heart was hospitalized after eating Brussels sprouts. Vitamin K, which is found in large quantities in this vegetable, prevented the action of anticoagulant drugs taken by the patient.

The decision to supplement or discontinue group K drugs should only be made by a physician, as excess of the nutrient due to prolonged high-dose intake can cause increased blood clotting and cause thrombosis.

What to look for when choosing vitamin K

It is useful to combine vitamin K intake with mono- and polyunsaturated fats, calcium, vitamin D3. Due to the fact that vitamin K is an activator of calcium absorption, preparations containing the last three elements help to completely eliminate the deficiency of nutrients important for skeletal growth and maintaining bone strength.

When deciding on an additional intake of vitamin K, it is necessary to take into account its main property - to influence blood clotting, which is important for people who constantly take anticoagulants.

Answers to popular questions about vitamin K:

Which vitamins are best combined with vitamin K?

Vitamin K is ideally combined with calcium and vitamin D3 to enhance the beneficial properties of each nutrient.

If you have enough vitamin K in your diet, should you buy supplements?

All vitamins are best absorbed in their natural form - from food. With a balanced diet, vitamin K is not required. The exception is the poor absorption of any vitamins by the body.

How can medicines interact with vitamin K?

Vitamin K absorption is affected by anticoagulants, antacids, antibiotics, aspirin, as well as drugs for cancer, seizures, high blood pressure.

Am I getting enough vitamin K?

The classic symptoms of vitamin K deficiency are nosebleeds, hemorrhages, long-term non-healing wounds, fatigue, osteoporosis, gastrointestinal disturbances.

Information sources:

https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminK-HealthProfessional/

https://ods. od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminK-Consumer/

od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminK-Consumer/

Diaper dermatitis in children: how to identify and treat Chlorella for the body. Is there any real benefit to algae?

Unresolved issues of vitamin and mineral support for patients undergoing bariatric surgery | Malykhina

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, the prevalence of obesity has been steadily increasing over the past few decades. This disease, which can rightfully be considered a non-infectious epidemic of the 21st century, is considered not only as a cosmetic problem, since it reduces the duration and quality of life. The high prevalence of obesity is a serious medical and social problem and is due to urbanization, a decrease in the physical activity of the population and the availability of high-calorie foods.

According to the WHO fact sheet of October 2017, in 2016, more than 1.9 billion people over the age of 18 were overweight in the world, of which over 650 million were obese [1].

According to the data of the ESSE-RF (Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases and Their Risk Factors in the Regions of the Russian Federation) multicenter observational Russian study conducted in 11 regions of the Russian Federation, in which 18,305 people took part (including 6,919 men and 11,386 women ,) at the age of 25–64 years, the prevalence of obesity in the population was 29.7% [2].

Obesity is not only a problem of the adult population. Worldwide, about 41 million children under the age of 5 are overweight or obese [1].

Chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (CVD), dyslipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA), musculoskeletal diseases and many cancers [3] have been shown to be associated with obesity, and even after minimal weight loss at the level of 5-10% of the original, the outcomes of these diseases significantly improve [4-9].

Unfortunately, to date, all existing conservative methods of treating obesity (diet, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, etc.) ultimately turn out to be ineffective, and maintaining the achieved result in terms of weight loss is the most difficult task for patients.

Bariatric surgery is currently recognized as the most effective and radical treatment for morbid obesity [10–15].

Bariatric surgery can lead to impressive results in terms of weight loss and improvement in patient health, but the development of vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies is a common and unavoidable problem in the postoperative period.

Various forms of nutritional deficiencies can develop after any type of bariatric surgery, and the more difficult the operation and the greater the percentage of excess weight loss, the more pronounced the degree of expected nutritional deficiency.

Many obese patients already initially have a deficiency of vitamins and microelements, in particular, a deficiency of vitamins D, B 1 , B 12 , iron, etc. [7, 16–29], therefore, it is necessary to identify and correct in a timely manner these deficient states are still at the preoperative stage.

[7, 16–29], therefore, it is necessary to identify and correct in a timely manner these deficient states are still at the preoperative stage.

Due to the high popularity of bariatric surgeries all over the world, the growing interest in them in Russia every year, the question of active dynamic postoperative monitoring and management of these patients in the long term after surgery is steadily rising.

VITAMIN AND MINERAL SUPPORT AFTER DIFFERENT TYPES OF BARIATRIC SURGERY

Depending on the type of bariatric surgery used (restrictive, malabsorptive), the daily requirement for vitamins, macro- and microelements varies, but always exceeds the daily requirement for non-operated patients.

To prevent the development of micronutrient deficiencies, all patients who have undergone bariatric surgery are recommended to take multivitamin complexes that include vitamins, macro- (calcium, phosphorus, etc.) and microelements: iron, zinc, selenium and copper [6, 15 , 30–33].

Due to the lack of specially developed “bariatric vitamin-mineral complexes” on the Russian pharmaceutical market, the curator has to prescribe affordable multivitamins in the pharmacy network that do not meet the requirements of International recommendations and do not contain enough copper, selenium, magnesium, manganese and other trace elements; in this connection, additional administration of iron preparations and fat-soluble vitamins, as well as calcium and vitamin D preparations is required.

IRON PRODUCTS

To prevent the development of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in patients after longitudinal gastric resection (GAR), gastric bypass (GAS), and biliopancreatic shunting (BPS) [23, 34], 45–60 mg of elemental iron per day should be prescribed [ 31-33], women of childbearing age are advised to increase the dose of elemental iron to 100 mg per day [33, 35, 36].

Ferrous salts are preferred due to their greater bioavailability, and the combined use of iron with vitamin C increases iron absorption [34, 37]. During pregnancy, ferrous sulfate 200 mg 2-3 times a day is prescribed [32]. To date, there are preparations containing non-ionized iron, which are multimolecular complexes of ferric hydroxide. Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated patients require further study. A separate study requires a preparation containing sucrosomal (liposomal) iron. However, one capsule of this drug contains 30 mg of liposomal iron, which requires the appointment of at least 2 capsules per day, which is off-label (appointment not recommended in the instructions for use of the drug). Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated bariatric patients are also not well understood.

During pregnancy, ferrous sulfate 200 mg 2-3 times a day is prescribed [32]. To date, there are preparations containing non-ionized iron, which are multimolecular complexes of ferric hydroxide. Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated patients require further study. A separate study requires a preparation containing sucrosomal (liposomal) iron. However, one capsule of this drug contains 30 mg of liposomal iron, which requires the appointment of at least 2 capsules per day, which is off-label (appointment not recommended in the instructions for use of the drug). Questions about the purpose, efficacy and tolerability of these drugs in operated bariatric patients are also not well understood.

Ferrous sulfate preparations are usually prescribed to patients after bariatric surgery due to good bioavailability, efficacy and low cost [6, 37-39]. In a systematic review, Manasanch et al. [40] showed that modified-release ferrous sulfate preparations were better tolerated and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, dyspepsia, constipation).

Iron preparations are available in a variety of dosage forms (drops, capsules, chewable tablets, oral syrups) and differ in the amount of elemental iron per dosage unit, the chemical structure of the iron, and the galenic form (rapid or phased release of the active ingredient) [ 41]. On the packaging of the drug, the content of the iron salt and the amount of equivalent elemental iron are usually indicated. When choosing a drug, you should focus on the amount of elemental iron. The composition of vitamin-mineral complexes registered in the Russian Federation includes 10-20 mg of elemental iron, which is insufficient for bariatric patients and requires additional prescription of iron preparations.

CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D

The daily dose of elemental calcium depends on the type of operation: after longitudinal gastric resection (LGA) and gastric bypass (GSH) - 1200–1500 mg; after biliopancreatic shunting (BPS), where the malabsorptive component is more pronounced - 1800–2400 mg [31, 32].

Calcium preparations are represented by organic calcium salts: citrate, gluconate, lactate, etc., and inorganic calcium salts: chloride, carbonate, phosphate [42, 43]. In patients undergoing bariatric surgery, it is preferable to prescribe calcium citrate preparations due to the fact that the bioavailability of calcium citrate is 2 times greater than the bioavailability of calcium carbonate [44]. The appointment of calcium citrate preparations is accompanied by a minimal risk of kidney stones due to its better solubility in water, and absorption does not depend on gastric pH and meal times. Therefore, calcium citrate preparations are the drugs of choice in patients with achlorhydria, inflammatory bowel disease, and in patients taking proton pump inhibitors and H 2 blockers [42, 43, 45]. Taking calcium citrate preparations is not accompanied by dyspepsia, since this salt does not neutralize hydrochloric acid and does not form carbon dioxide [43].

A meta-analysis by Sakhaee K. 1999 showed that calcium absorption from calcium citrate was 22–27% higher than from calcium carbonate, both on an empty stomach and when fed together, and thus a calcium citrate preparation can be taken both before, during and after meals [46].

1999 showed that calcium absorption from calcium citrate was 22–27% higher than from calcium carbonate, both on an empty stomach and when fed together, and thus a calcium citrate preparation can be taken both before, during and after meals [46].

To date, dietary supplements are registered in Russia, which include calcium citrate and vitamin D 3 . However, its calcium citrate content is only 250 mg per tablet, and to achieve the recommended daily requirement for elemental calcium, 6 to 8 tablets per day must be taken, which creates some inconvenience for patients and is not economically viable. The Russian pharmaceutical market also presents a combination drug that includes citrate and calcium carbonate salts, as well as vitamin D and other trace elements; however, the manufacturer does not indicate the percentage of calcium salts in the preparation.

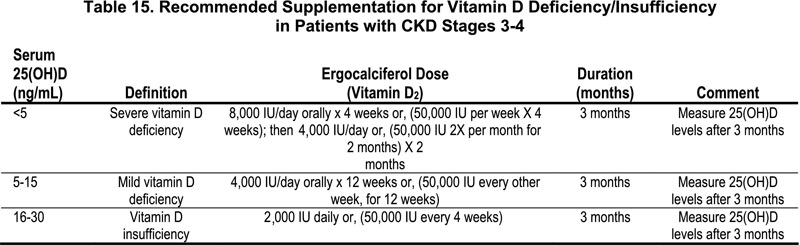

According to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) [31] and the Obesity Task Force Practice Guidelines [32], the recommended preventive dose of vitamin D in patients undergoing weight loss surgery should be based on baseline levels of vitamin D in blood serum and can reach 50,000 IU/day, and the recommended maintenance dose of vitamin D at an initial level of 25(OH)D> 30 ng/ml is 3000 IU.

FAT-SOLUBLE VITAMINS PRODUCTS

All patients, according to international recommendations [31, 32], should take fat-soluble vitamins (A, E, K), the dose of which depends on the type of bariatric surgery: after PRV and GSh - vitamin A - 5000 IU ( is part of the vitamin-mineral complexes), vitamin K - 90-120 mcg.

Given the more pronounced hypoabsorption of fats and the possible development of steatorrhea after BPD, large doses of fat-soluble vitamins are required: vitamin A - 10,000 IU, vitamin K - 300 mcg.

The question of vitamin E dosages after various types of bariatric surgery is debatable. Although the optimal dose for the prevention and/or treatment of vitamin E deficiency after HSS and BPD is not known, the recommended dose range is from 300–600 mg [47] to 800–1200 mg [48].

FOLIC ACID AND VITAMIN B SUPPLEMENTS

12 Supplementation of folic acid supplements is usually not required (unless there is an initial deficiency), since usually 400-600 micrograms of folic acid are included in vitamin-mineral complexes. Women of childbearing age are recommended to prescribe 800-1000 micrograms of folic acid per day [30, 31].

Women of childbearing age are recommended to prescribe 800-1000 micrograms of folic acid per day [30, 31].

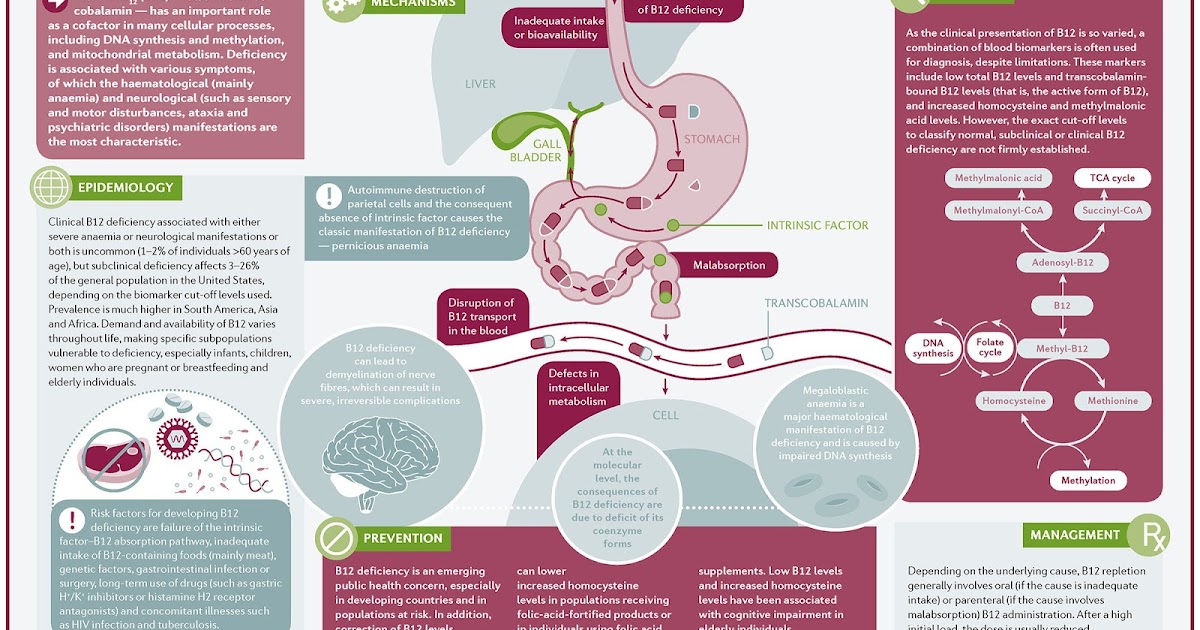

All patients after bariatric surgeries (PVR, GS, BPS) should be prescribed vitamin B 12 [31, 32]. Absorption of vitamin B 12 is carried out with the participation of the intrinsic factor of Castle (Intrinsic factor, IF), which is produced by the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa. However, approximately 1% of oral vitamin B 12, is passively absorbed, even in the absence of intrinsic factor [23]. Therefore, oral intake of vitamin B 12 at a dose of 350–500 µg guarantees the absorption of the required dose of this vitamin [23, 31]. Currently, the oral form of vitamin B 12 is not registered in Russia. There are alternative regimens for prescribing vitamin B 12 [34]: 1000 µg IM once a month, 3000 µg IM once every 6 months, or 500 µg intranasally every week (this form of vitamin B 12 is not available in Russia). registered).

registered).

OTHER MEDICINES

Other mineral deficiencies (zinc, copper, selenium, potassium, magnesium) and vitamin B 9 deficiency0740 6 are described after bariatric surgery [7, 23, 31, 34], therefore, these components should be included in vitamin-mineral complexes. If the above deficiencies are identified, it is necessary to carry out an appropriate correction in accordance with approved clinical guidelines.

CONCLUSION

Despite the fact that all obese patients who have undergone bariatric surgery need vitamin and mineral support, today, on the pharmaceutical market in Russia, there are no vitamin and mineral complexes that would fully satisfy the daily needs of these patients. patients in vitamins and microelements, which creates difficulties in the prevention of long-term postoperative complications.

Under these conditions, doctors have to combine the prescription of available multivitamins in the pharmacy network, iron, calcium and vitamin D preparations, fat-soluble vitamins in order to achieve optimal daily doses for patients after various bariatric surgeries.

This creates inconvenience, because in order to achieve optimal dosages of vitamins, macro- and microelements, patients have to simultaneously take a large number of drugs (up to 10 tablets or capsules per day), which leads to a violation of adherence to treatment (compliance), partial or complete skipping medications and increasing the cost of their purchase, as well as the inevitable increase in postoperative complications, which are caused by metabolic disorders.

The development and appearance on the Russian pharmaceutical market of vitamin and mineral supplements, balanced in all necessary components and meeting the recommended daily needs of patients after bariatric surgery, would reduce the incidence of long-term metabolic disorders by increasing compliance, ease of taking the dosage form of the drug and reducing the cost of purchase of the drug.

Thus, pharmaceutical companies are faced with the task of developing domestic vitamin and mineral complexes that would meet the needs of patients after bariatric surgery and at the same time combine ease of use and economic accessibility. Currently, Russian specialists have come close to the manufacture and clinical testing of such specialized vitamin and mineral preparations, and in the near future they will be ready to present them to a wide audience, both doctors and patients.

Currently, Russian specialists have come close to the manufacture and clinical testing of such specialized vitamin and mineral preparations, and in the near future they will be ready to present them to a wide audience, both doctors and patients.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Funding source. Preparation and publication of the manuscript were carried out at the personal expense of the team of authors.

Conflict of interest. The authors declare no apparent or potential conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Participation of authors. All authors made a significant contribution to the study and preparation of the article, read and approved the final version of the article before publication.

1. who.int [Internet]. world health organization. media center. Fact sheet "obesity and overweight". [updated 2018 Feb 16; cited 2019 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ru/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

2. Muromtseva G.A., Kontsevaya A.V., Konstantinov V.V. ., etc. Prevalence of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in the Russian population in 2012–2013. Results of the ESSE-RF study. // Cardiovascular therapy and prevention. - 2014. - T. 13. - No. 6. — S. 4-11. [Muromtseva GA, Kontsevaya AV, Konstantinov VV, et al. The prevalence of non-infectious diseases risk factors in the Russian population in 2012-2013 years. The results of ECVD-RF. Cardiovascular Therapy and Prevention. 2014;13(6):4-11. (In Russ).] DOI:10.15829/1728-8800-2014-6-4-11

Muromtseva G.A., Kontsevaya A.V., Konstantinov V.V. ., etc. Prevalence of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases in the Russian population in 2012–2013. Results of the ESSE-RF study. // Cardiovascular therapy and prevention. - 2014. - T. 13. - No. 6. — S. 4-11. [Muromtseva GA, Kontsevaya AV, Konstantinov VV, et al. The prevalence of non-infectious diseases risk factors in the Russian population in 2012-2013 years. The results of ECVD-RF. Cardiovascular Therapy and Prevention. 2014;13(6):4-11. (In Russ).] DOI:10.15829/1728-8800-2014-6-4-11

3. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625-1638. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa021423

4. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. 1998.

1998.

5. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

6. Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient--2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21 Suppl 1:S1-27. DOI:10.1002/oby.20461

7. Bodunova N.A. Influence of bariatric operations on the content of vitamins in obese patients: Abstract of the thesis. dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. — M.; 2016. [Bodunova NA. Vliyanie bariatricheskikh operatsiy na soderzhanie vitaminov u bol’nykh s ozhireniem. [dissertation] Moscow; 2016. (In Russ).]

8. Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547-559. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013

Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547-559. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013

9. Mattar SG, Velcu LM, Rabinovitz M, et al. Surgically-induced weight loss significantly improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome. Ann Surg. 2005;242(4):610-617; discussion 618-620. DOI:10.1097/01.sla.0000179652.07502.3f

10. Karlsson J, Taft C, Ryden A, et al. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31(8):1248-1261. DOI:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573

11. Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683-2693. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa035622

12. Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219-234. DOI:10.1111/joim.12012

DOI:10.1111/joim.12012

13. Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, et al. European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. obes facts. 2015;8(6):402-424. DOI:10.1159/000442721

14. Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822-1832. DOI:10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z

15. Russian Society of Surgeons, Society of Bariatric Surgeons. Clinical guidelines for bariatric and metabolic therapy. — M.; 2014. [Rossiyskoe obshchestvo khirurgov, obshchestvo bariatricheskikh khirurgov. Klinicheskie rekomendatsii po bariatricheskoy i metabolicheskoy terapii. Moscow; 2014. (In Russ).]

16. Kimmons JE, Blanck HM, Tohill BC, et al. Associations between body mass index and the prevalence of low micronutrient levels among US adults. MedGenMed. 2006;8(4):59.

17. Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, et al. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clinic Nutr. 2000;72(3):690-693. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690

18. Cepeda-Lopez AC, Aeberli I, Zimmermann MB. Does obesity increase the risk for iron deficiency? A review of the literature and the potential mechanisms. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2010;80(4-5):263-270. DOI:10.1024/0300-9831/a000033

Cepeda-Lopez AC, Aeberli I, Zimmermann MB. Does obesity increase the risk for iron deficiency? A review of the literature and the potential mechanisms. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2010;80(4-5):263-270. DOI:10.1024/0300-9831/a000033

19. Marreiro DN, Fisberg M, Cozzolino SM. Zinc nutritional status and its relationships with hyperinsulinemia in obese children and adolescents. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2004;100(2):137-149. DOI:10.1385/bter:100:2:137

20. Toh SY, Zarshenas N, Jorgensen J. Prevalence of nutrient deficiencies in bariatric patients. nutrition. 2009;25(11-12):1150-1156. DOI:10.1016/j.nut.2009.03.012

21. Bavaresco M, Paganini S, Lima TP, et al. Nutritional course of patients submitted to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20(6):716-721. DOI:10.1007/s11695-008-9721-6

22. Flankbaum L, Belsley S, Drake V, et al. Pre-operative nutritional status of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(7):1033-1037. DOI:10. 1016/j.gassur.2006.03.004

1016/j.gassur.2006.03.004

23. Allied Health Sciences Section Ad Hoc Nutrition C, Aills L, Blankenship J, et al. ASMBS Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S73-108. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.002

24. Xanthakos SA. Nutritional deficiencies in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Pediatric Clin North Am. 2009;56(5):1105-1121. DOI:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.07.002

25. Aasheim ET, Hofso D, Hjelmesaeth J, et al. Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clinic Nutr. 2008;87(2):362-369. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/87.2.362

26. Ernst B, Thurnheer M, Schmid SM, Schultes B. Evidence for the necessity to systematically assess micronutrient status prior to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19(1):66-73. DOI:10.1007/s11695-008-9545-4

27. de Luis DA, Pacheco D, Izaola O, et al. Micronutrient status in morbidly obese women before bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(2):323-327. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.015

DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.015

28. Lefebvre P, Letois F, Sultan A, et al. Nutrient deficiencies in patients with obesity considering bariatric surgery: a cross-sectional study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):540-546. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.003

29. Bodunova NA, Askerkhanov RG, Khatkov IE, et al. Influence of bariatric surgeries on vitamin metabolism in obese patients. // Therapeutic archive. - 2015. - T. 87. - No. 2. - C. 70-76. [Bodunova NA, Askerkhanov RG, Khat'kov IE, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on vitamin metabolisms in obese patients. Ter Arkh. 2015;87(2):70-76. (In Russ).] DOI:10.17116/terarkh301587270-76

30. Dedov I.I., Melnichenko G.A., Shestakova M.V., et al. National clinical guidelines for the treatment of morbid obesity in adults. 3rd revision (treatment of morbid obesity in adults). // Obesity and metabolism. - 2018. - T. 15. - No. 1. - S. 53-70. [Dedov II, Mel'nichenko GA, Shestakova MV, et al. Russian national clinical recommendations for morbid obesity treatment in adults. 3rd revision (Morbid obesity treatment in adults). obesity and metabolism. 2018;15(1):53-70. (In Russ).] DOI:10.14341/OMET2018153-70

3rd revision (Morbid obesity treatment in adults). obesity and metabolism. 2018;15(1):53-70. (In Russ).] DOI:10.14341/OMET2018153-70

31. Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):727-741. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018

32. Busetto L, Dicker D, Azran C, et al. Practical Recommendations of the Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity for the Post-Bariatric Surgery Medical Management. obes facts. 2017;10(6):597-632. DOI:10.1159/000481825

33. O’Kane M, Pinkney J, Aasheim ET, et al. BOMSS Guidelines on peri-operative and postoperative biochemical monitoring and micronutrient replacement for patients undergoing bariatric surgery. BOMSS; 2014.

34. Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery: Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and non surgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S109-184. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.009

Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S109-184. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.009

35. Parkes E. Nutritional Management of Patients after Bariatric Surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):207-213. DOI:10.1097/00000441-200604000-00007

36. Malinowski SS. Nutritional and Metabolic Complications of Bariatric Surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):219-225. DOI:10.1097/00000441-200604000-00009

37. Love AL, Billett HH. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and iron deficiency: True, true, true and related. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(5):403-409. DOI:10.1002/ajh.21106

38. Wax JR, Pinette MG, Cartin A, Blackstone J. Female reproductive issues following bariatric surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(9):595-604. DOI:10.1097/01.ogx.0000279291.86611.46

39. Marinella MA. Anemia following Roux-en-Y surgery for morbid obesity: a review. South Med J. 2008;101(10):1024-1031. DOI:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817cf7b7

40. Cancelo-Hidalgo MJ, Castelo-Branco C, Palacios S, et al. Tolerability of different oral iron supplements: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):291-303. DOI:10.1185/03007995.2012.761599

Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):291-303. DOI:10.1185/03007995.2012.761599

41. Belovol A.N., Knyazkova I.I. From iron metabolism to issues of pharmacological correction of its deficiency. // Faces of Ukraine. - 2015. - No. 4. — S. 46-51. [Bilovol AN, Knyaz'kova II. From Iron Metabolism to the Issues of Pharmacological Correction of Iron Deficiency. Likey Ukraine'ny. 2015;(4):46-51. (In Russ).]

42. Trailokya A, Srivastava A, Bhole M, Zalte N. Calcium and Calcium Salts. J Assoc Physicians India. 2017;65(2):100-103.

43. Gromova OA, Torshin I.Yu., Gogoleva IV, et al. Organic calcium salts: prospects for use in clinical practice. // RMJ. - 2012. - T. 20. - No. 28. - S. 1407-1411. [Gromova OA, Torshin IY, Gogoleva IV, et al. Organicheskie soli kal'tsiya: perspektivy ispol'zovaniya v klinicheskoy praktike. RMZh. 2012;20(28):1407-1411. (In Russ).]

44. Tondapu P, Provost D, Adams-Huet B, et al. Comparison of the absorption of calcium carbonate and calcium citrate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2009;19(9):1256-1261. DOI:10.1007/s11695-009-9850-6

Obes Surg. 2009;19(9):1256-1261. DOI:10.1007/s11695-009-9850-6

45. Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Dugieva M.Z. Postmenopausal osteoporosis: calcium preparations in a modern strategy for prevention and treatment. // RMJ. Mother and child. - 2017. - T. 25. - No. 15. - S. 1135-1139. [Dobrohotova YE, Dugieva MZ. Postmenopauzal'nyy osteoporosis: preparaty kal'tsiya v sovremennoy strategii profilaktiki i lecheniya. RMZh. Mat' i childa. 2017;25(15):1135-1139. (In Russ).]

46. Sakhaee K, Bhuket T, Adams-Huet B, Rao DS. Meta-analysis of calcium bioavailability: a comparison of calcium citrate with calcium carbonate. Am J Ther. 1999;6(6):313-321. DOI:10.1097/00045391-199911000-00005

47. Allied Health Sciences Section Ad Hoc Nutrition C, Aills L, Blankenship J, et al. ASMBS Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):S73-108. DOI:10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.002

48. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery.

5 mcg

5 mcg