How to handle tantrums of a child

How to Handle Child Tantrums and Meltdowns | Behavior Problems

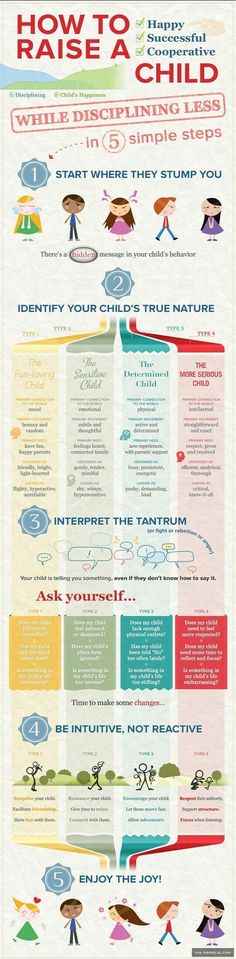

The first thing we have to do to manage tantrums is to understand them. That is not always as easy as it sounds, since tantrums and meltdowns are generated by a lot of different things: fear, frustration, anger, sensory overload, to name a few. And since a tantrum isn’t a very clear way to communicate (even though it may be a powerful way to get attention), parents are often in the dark about what’s driving the behavior.

It’s useful to think of a tantrum as a reaction to a situation a child can’t handle in a more grown-up way—say, by talking about how he feels, or making a case for what he wants, or just doing what he’s been asked to do. Instead he is overwhelmed by emotion. And if unleashing his feelings in a dramatic way — crying, yelling, kicking the floor, punching the wall, or hitting a parent — serves to get him what he wants (or out of whatever he was trying to avoid), it’s a behavior that he may come to rely on.

That doesn’t mean that tantrums are consciously willful, or even voluntary. But it does mean that they’re a learned response. So the goal with a child prone to tantrums is to help him unlearn this response, and instead learn other, more mature ways to handle a problem situation, like compromising, or complying with parental expectations in exchange for some positive reward.

Make an assessment

The first step is to get a picture of what triggers your particular child’s tantrums. Mental health professionals call this a “functional assessment,” which means looking at what real-life situations seem to generate tantrums — specifically, at what happens immediately before, during, and after the outbursts that might contribute to their happening again.

Sometimes a close look at the pattern of a child’s tantrums reveals a problem that needs attention: a traumatic experience, abuse or neglect, social anxiety, ADHD, or a learning disorder. When children are prone to meltdowns beyond the age in which they are typical, it’s often a symptom of distress that they are struggling to manage. That effort breaks down at moments that require self-discipline they don’t yet have, like transitioning from something they enjoy to something that’s difficult for them.

That effort breaks down at moments that require self-discipline they don’t yet have, like transitioning from something they enjoy to something that’s difficult for them.

“A majority of kids who have frequent meltdowns do it in very predictable, circumscribed situations: when it’s homework time, bedtime, time to stop playing,” explains Vasco Lopes, PsyD, a clinical psychologist. “The trigger is usually being asked to do something that’s aversive to them or to stop doing something that is fun for them. Especially for children who have ADHD, something that’s not stimulating and requires them to control their physical activity, like a long car ride or a religious service or visiting an elderly relative, is a common trigger for meltdowns.”

Learned behavior

Since parents often find tantrums impossible to tolerate—especially in public—the child may learn implicitly that throwing a tantrum can help him get his way. It becomes a conditioned response. “Even if it only works five out of 10 times that they tantrum, that intermittent reinforcement makes it a very solid learned behavior,” Dr. Lopes adds. “So they’re going to continue that behavior in order to get what they want.”

Lopes adds. “So they’re going to continue that behavior in order to get what they want.”

One of the goals of the functional assessment is to see if some tantrum triggers might be eliminated or changed so they’re not as problematic for the child. “If putting on the child’s shoes or leaving for school is the trigger, obviously we can’t make it go away,” explains Steven Dickstein, MD, who is both a pediatrician and child and adolescent psychiatrist. But sometimes we can change the way parents and other caregivers handle a situation — to defuse it. This could translate into giving kids more warning that a task is required of them, or structuring problematic activities in ways that reduce the likelihood of a tantrum.

“Anticipating those triggers, and modifying them so that it’s easier for the child to engage in that activity is really important,” says Dr. Lopes. “For example, if homework is really difficult for a child, because she has underlying attention, organization or learning issues, she might have outbursts right before she’s supposed to start her homework. So we say to parents, ‘How can we make doing homework more palatable for her?’ We can give her frequent breaks, support her in areas she has particular difficulty with, organize her work, and break intimidating tasks into smaller chunks.”

So we say to parents, ‘How can we make doing homework more palatable for her?’ We can give her frequent breaks, support her in areas she has particular difficulty with, organize her work, and break intimidating tasks into smaller chunks.”

Another goal is to consider whether the expectations for the child’s behavior are developmentally appropriate, Dr. Dickstein notes, for his age and his particular level of maturity. “Can we modify the environment to make it match the child’s abilities better, and foster development towards maturing?”

It’s important for parents to understand two things: first of all, avoiding a tantrum before it begins does not mean “giving in” to a child’s demands. It means separating the unwanted tantrum response from other issues, such as compliance with parental requests. And second, by reducing the likelihood of a tantrum response, you are also taking away the opportunity for reinforcement of that response. When kids don’t tantrum, they learn to deal with needs, desires, and setbacks in a more mature way, and that learning itself reinforces appropriate responses. Fewer tantrums now means…fewer tantrums later.

Fewer tantrums now means…fewer tantrums later.

Responding to tantrums

When tantrums occur, the parent or caregiver’s response affects the likelihood of the behavior happening again. There are lots of very specific protocols to help parents respond consistently, in ways that will minimize tantrum behavior later. They range from Ross Greene’s seminal approach, Collaborative & Proactive Solutions, to step-by-step parent-training programs like Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and Parent Management Training. They have in common the starting point that parents resist the temptation to end the tantrum by giving the child what he wants when he tantrums. For outbursts that aren’t dangerous, the goal is to ignore the behavior, to withdraw all parental attention, since even negative attention like reprimanding or trying to persuade the child to stop has been found positively reinforce the behavior.

Attention is withheld from behavior you want to discourage, and lavished instead on behaviors you want to encourage: when a child makes an effort to calm down or, instead of tantruming, complies or proposes a compromise. “By positively reinforcing compliance and appropriate responses to frustration,” says Dr. Lopes, “you’re teaching skills and—since you can’t comply with a command and tantrum at the same time—simultaneously decreasing that aggressive noncompliant tantrum behavior.”

“By positively reinforcing compliance and appropriate responses to frustration,” says Dr. Lopes, “you’re teaching skills and—since you can’t comply with a command and tantrum at the same time—simultaneously decreasing that aggressive noncompliant tantrum behavior.”

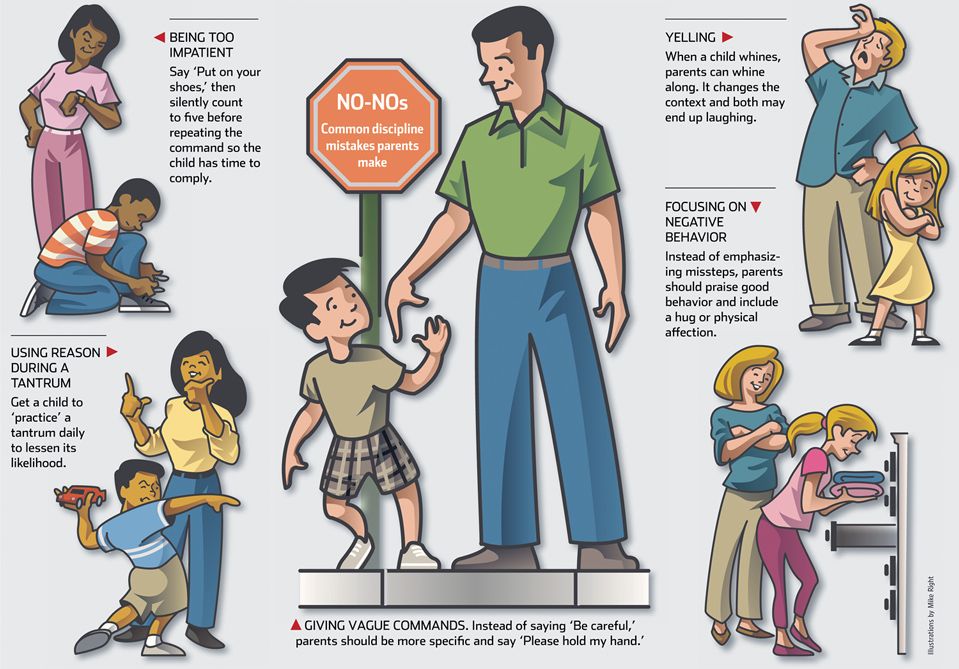

One thing you don’t want to do is try to reason with a child who is upset. As Dr. Dickstein puts it, “Don’t talk to the kid when he’s not available.” You want to encourage a child to practice at negotiation when he’s not blowing up, and you’re not either. You may need to teach techniques for working through problems, break them down step by step for kids who are immature or have deficits in this kind of thinking and communication.

Modeling calm behavior

And you need to model the kind of negotiation you want your child to learn. “Parents should take time outs, too,” notes Dr. Dickstein. ” When you get really angry you need to just take yourself out of the situation. You can’t problem solve when you’re upset—your IQ drops about 30 percent when you are angry. ”

”

Being calm and clear about behavioral expectations is important because it helps you communicate more effectively with a child. “So it’s not, ‘You need to behave today,’” Dr. Lopes says. “It’s, ‘You need to be seated during mealtime, with your hands to yourself, and saying only positive words.’ Those are very observable, concrete things that the child knows what’s expected and that the parent can reinforce with praise and rewards.”

Both you and your child need to build what Dr. Dickstein calls a toolkit for self-soothing, things you can do to calm down, like slow breathing, to relax, because you can’t be calm and angry at the same time. There are lots of techniques, he adds, but “The nice thing about breathing is it’s always available to you.”

Frequently Asked Questions

How can parents deal with toddler tantrums?To deal with toddler tantrums, first try to identify the things that might trigger these tantrums and remove them from the child’s environment. During a tantrum, the goal is to ignore the behavior and withdraw all attention, so the child learns that tantrums won’t get them what they want.

During a tantrum, the goal is to ignore the behavior and withdraw all attention, so the child learns that tantrums won’t get them what they want.

To handle a child having a meltdown, try to ignore the behavior and withdraw all parental attention, since even negative attention like reprimanding or persuasion has been found to positively reinforce the behavior.

How can parents stop tantrums?To stop tantrums, parents can identify and remove things that may trigger a tantrum, ignore active meltdowns, give kids attention and praise when they compromise, and model calm behavior.

Temper Tantrums (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

Temper tantrums can be frustrating for any parent. But instead of looking at them as disasters, treat tantrums as opportunities for education.

Why Do Kids Have Tantrums?

Temper tantrums range from whining and crying to screaming, kicking, hitting, and breath-holding spells. They're equally common in boys and girls and usually happen between the ages of 1 to 3.

They're equally common in boys and girls and usually happen between the ages of 1 to 3.

Some kids may have tantrums often, and others have them rarely. Tantrums are a normal part of child development. They're how young children show that they're upset or frustrated.

Tantrums may happen when kids are tired, hungry, or uncomfortable. They can have a meltdown because they can't have something they want (like a toy or candy) or can’t get someone to do what they want (like getting a parent to pay attention to them immediately or getting a sibling to give up the tablet). Learning to deal with frustration is a skill that children gain over time.

Tantrums are common during the second year of life, when language skills are developing. Because toddlers can't always say what they want or need, and because words describing feelings are more complicated and develop later, a frustrating experience may cause a tantrum. As language skills improve, tantrums tend to decrease.

Toddlers want independence and control over their environment — more than they can actually handle. This can lead to power struggles as a child thinks "I can do it myself" or "I want it, give it to me." When kids discover that they can't do it and can't have everything they want, they may have a tantrum.

This can lead to power struggles as a child thinks "I can do it myself" or "I want it, give it to me." When kids discover that they can't do it and can't have everything they want, they may have a tantrum.

How Can We Avoid Tantrums?

Try to prevent tantrums from happening in the first place, whenever possible. Here are some ideas that may help:

- Give plenty of positive attention. Get in the habit of catching your child being good. Reward your little one with praise and attention for positive behavior. Be specific about praising behaviors you want to see happen more often (such as, “I like the way you said please and waited for your milk” or “Thank you for sharing the blocks with your sister.”)

- Try to give toddlers some control over little things. Offer minor choices such as "Do you want orange juice or apple juice?" or "Do you want to brush your teeth before or after taking a bath?" This way, you aren't asking "Do you want to brush your teeth now?" — which of course will be answered "no.

" Allow control when it doesn’t really matter. Instead of struggling over an outfit your child puts on that doesn’t match, for example, consider whether this may be an opportunity to allow self-expression and independence and if it really makes a difference given the day's schedule.

" Allow control when it doesn’t really matter. Instead of struggling over an outfit your child puts on that doesn’t match, for example, consider whether this may be an opportunity to allow self-expression and independence and if it really makes a difference given the day's schedule. - Keep off-limits objects out of sight and out of reach. This makes struggles less likely. Obviously, this isn't always possible, especially outside of the home where the environment can't be controlled.

- Distract your child. Try offering something else in place of what they can't have. Start a new activity to replace the frustrating or forbidden one (for example, if your child is jumping on the couch, ask them to come help you “cook” by offering a plastic container and wooden spoon. Then you can praise them for helping or following directions, rather than having them start a tantrum or refuse to get down). Or simply change the environment. Take your toddler outside or inside or move to a different room.

- Help kids learn new skills and succeed. Help kids learn to do things. Praise them to help them feel proud of what they can do. Also, start with something simple before moving on to more challenging tasks.

- Consider the request carefully when your child wants something. Is it outrageous? Maybe it isn't. Choose your battles. It's even OK to change your mind if you originally said no — but find a way to allow the desired treat as a reward for good behavior.

- Know your child's limits. If you know your toddler is tired, it's not the best time to go grocery shopping or try to squeeze in one more errand. Hungry kids are more likely to demand food in the store than children who have just had a meal (just like adults!).

What Should I Do During a Tantrum?

Keep your cool when responding to a tantrum. Don't complicate the problem with your own frustration or anger. Remind yourself that your job is helping your child learn to calm down. So you need to be calm too.

So you need to be calm too.

Tantrums should be handled differently depending on why your child is upset. Sometimes, you may need to provide comfort. If your child is tired or hungry, it's time for a nap or a snack. Other times, its best to ignore an outburst or distract your child with a new activity.

If a tantrum is happening to get attention from parents, one of the best ways to reduce this behavior is to ignore it. If a tantrum happens after your child is refused something, stay calm and don't give a lot of explanations for why your child can't have what they want. Move on to another activity with your child.

If a tantrum happens after your child is told to do something they don't want to do, it's best to ignore the tantrum. But be sure that you follow through on having your child complete the task after they're calm.

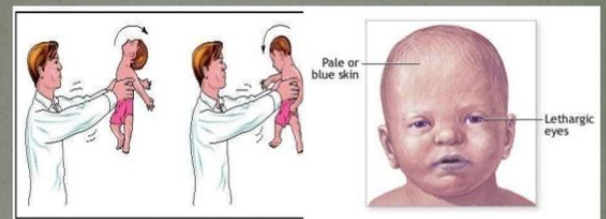

Kids who are in danger of hurting themselves or others during a tantrum should be taken to a quiet, safe place to calm down. This also applies to tantrums in public places.

If a safety issue is involved and a toddler repeats the forbidden behavior after being told to stop, use a time-out by sitting the child on a designated chair or in the corner for just a few minutes. Be nearby so that you can supervise, but do not interact until they are calm. Be consistent. Don't give in on safety issues.

Preschoolers and older kids are more likely to use tantrums to get their way if they've learned that this behavior works. For school-age kids, it's appropriate to send them to their rooms to cool off while paying little attention to the behavior.

Let your child know that you will tell them when the time-out is over and that the sooner they are calm and quiet, the sooner it will end. This is empowering — kids can affect the outcome by their own actions, and thus gain a sense of control that was lost during the tantrum.

Do not reward your child's tantrum by giving in. This will only prove to your little one that the tantrum was effective.

Consider making a “chill out” or “calm down” spot in your home (some teachers use this in preschool, as well). Use a soft cushion and provide books, a stuffed animal, some soft music, and other calming activities in a place where others won’t disturb the child. Encourage your child to go to the spot when angry or upset — not as a punishment, but as a choice and an opportunity to learn to calm down and control frustration.

What Should I Do After a Tantrum?

Praise your child for regaining control — for example, "I like how you calmed down."

Kids may be especially vulnerable after a tantrum when they know they've been less than adorable. Now (when your child is calm) is the time for a hug and reassurance that your child is loved, no matter what. If your child is old enough to discuss the problem, help them come up with some other ways they might have expressed their frustration.

Make sure your child gets enough sleep. With too little sleep, kids can become hyper, disagreeable, and have extremes in behavior. Getting enough sleep can greatly reduce tantrums. Find out how much sleep is needed at your child’s age. Most kids' sleep needs fall within a set range of hours based on their age, but each child is unique.

Getting enough sleep can greatly reduce tantrums. Find out how much sleep is needed at your child’s age. Most kids' sleep needs fall within a set range of hours based on their age, but each child is unique.

When Should I Call the Doctor?

Talk to your doctor if:

- You often feel angry or out of control when you respond to tantrums.

- You keep giving in to try to avoid your child acting out.

- The tantrums cause a lot of bad feelings between you and your child or you and your partner.

- The tantrums happen more often, are more intense, or last longer.

- Your child often self-harms or hurts others.

- Your child seems very disagreeable, argues a lot, and hardly ever cooperates.

Your doctor also can check for any health problems that may add to the tantrums, although this is not common. Sometimes, hearing or vision problems, a chronic illness, language delays, or a learning disability can make kids more likely to have tantrums.

Remember, tantrums usually aren't cause for concern and generally stop on their own. As kids mature, they gain self-control. They learn to cooperate, communicate, and cope with frustration. Less frustration and more control will mean fewer tantrums — and happier parents.

How to cope with a child's tantrum: advice from a psychologist

Even the most obedient and quiet child must have at least once unpleasantly surprised his parents with a tantrum. Screaming, growing crying, swearing and aggression towards an adult in the form of bites and pushes - this phenomenon always looks like an emotional explosion that is difficult to extinguish. How to properly respond to tantrums? How to behave with the baby when he calms down? These questions for "Oh!" psychologist Natalya Gorlova answers.

Natalia Gorlova, developmental psychologist, existential therapist, lecturer at the Department of Developmental Psychology and Counseling, Siberian Federal University

What the child feels

If a child's tantrum can frighten, irritate or lead an adult into a stupor, then the child himself at this moment experiences a more complex range of negative emotions. Depending on what caused the emotional "fire", the baby may feel anger, anger, rage, aggression, anxiety, fear, grief, disappointment.

Depending on what caused the emotional "fire", the baby may feel anger, anger, rage, aggression, anxiety, fear, grief, disappointment.

Causes of children's tantrums

While a child is very young and cannot cope with his emotions, even physiological reasons can cause hysterics in him. He is tired, hungry, wants to sleep, bored, endured stress, an adult wants to give him a bitter medicine or, conversely, does not give him a toy or sweet, the kid is carried away playing in the sandbox with friends, and he is suddenly taken home - all this can lead to hysteria .

If a child experiences an age crisis, then the manifestations of this emotional explosion can be very vivid. In a conversation about the crisis of three years, it was noted that the child during this period strives both in desires and in actions to be independent, independent of an adult, shows negativism and stubbornness. All this can increase the intensity of hysteria.

How an adult should behave

Distract. Try to stop the tantrum at the very beginning by diverting the child to something, switching his attention.

Try to stop the tantrum at the very beginning by diverting the child to something, switching his attention.

Don't interfere. If you failed to distract the child, then the tantrum will end on its own in about 15 minutes. During this time, try to speak to the child calmly, confidently, firmly, but not harshly.

Remain calm. Please do not show your strong feelings at this moment: reciprocal aggression will not lead to anything good. It is better to leave the child alone for these 15 minutes than to try to call him to order with screams and slaps. Learn to control yourself. And for this, you must feel good: if you are tired, hungry or have not had enough sleep, it will be harder for you to react calmly to a tantrum.

Show confidence. The child should understand from your behavior and tone of voice: you know that the tantrum is temporary, that it will end soon.

How to talk to children after a tantrum

It is better to communicate with a child at the level of his eyes, that is, to sit down to have a conversation "on an equal footing". Your voice should be calm, firm and confident.

Your voice should be calm, firm and confident.

Avoid "You mustn't" and even more so "Don't you dare": this does not explain why you require a certain behavior from a child. Dress your demand in the form of a request: "I don't want you to do this."

As noted above, the tantrum may be caused by the fact that the child did not get what he wanted. From a very early age, try to negotiate with the baby: "We will do what you want, but under certain conditions." For example: "You will get dessert, but only when you have dinner", "You can go for a walk, but first clean up your table."

When to Be Steadfast

Sometimes, if what a child wants is not possible or acceptable, all you have to do is firmly state your “no” or “no”. Sometimes this can and should be done without excuses and explanations, by the right of the elder. This is what you need to do in cases where the child puts himself in danger and you do not have time to explain to him why he is wrong: “You will not cross the road alone and run a red light. No, I forbid doing that", "Don't touch the boiling kettle, you can't!". Then, in a calm environment, tell the child why such actions are dangerous.

No, I forbid doing that", "Don't touch the boiling kettle, you can't!". Then, in a calm environment, tell the child why such actions are dangerous.

Try to use the words “no” and “no” only in emergency and dangerous situations. If you say them too often, they will lose their value, and the child will stop listening to your demands.

According to attachment theory, a child's willingness to obey depends on a strong connection with the parents. If the baby feels their protection, care, perceives mom and dad as his support, he follows their instructions - this is understandable for him and does not cause protest. As Lyudmila Petranovskaya writes, the more parents are “their own” for a child, the more natural it is for him to obey them. It is important that the child be sure that he can count on you in any situations, and especially in difficult ones.

See also:

8 tips from a psychologist on how to raise a confident child

7 tips to help increase emotional stability in children

How to help your child overcome fear: 5 effective techniques

5 Photo:

6 Portrait/Maria Evseyeva/VGstockstudio/ Shutterstock. com

com childrenupbringingdevelopmentpsychological adviceemotional intelligence

8 tips on how to deal with children's temper tantrums

Almost all parents know the feeling of helplessness and even despair when, during a child's tantrum, they suddenly realize that they cannot control the process. Being a calm, reasonable, accepting and responsible adult in such a situation is not very easy. But you can learn this.

Tantrums and simply defiant behavior can occur in people of any gender and age. Yes, most often uncontrolled fits of anger are typical for children from one and a half to three years old, simply because speech is not yet sufficiently developed and the child, desperate to be understood by the outside world, tries to express himself by rolling on the supermarket floor. But you can face childish aggression and hysteria at the age of five, and at 10, and at 13. Less common, but the consequences are much more serious and more difficult to cope with.

From the age of three, the child's behavior should gradually level off by learning to recognize and control his impulses and desires. Gradually, however, not as quickly as we would like, the volitional sphere is born. And the notorious free will. When I, every time, as soon as the red veil begins to cover my eyes, I can say: “Stop. Not today". And exhaling calmly, get away from the phenomenon or object that irritates me. Or, on the contrary, decide that "today is a good time for a fight, I choose action" and use all the power of your aggression to achieve the goal.

But it's great if we control our states and use their energy, and not they use us. To do this, you need to learn to recognize these very states, understand their mechanisms and begin to manage yourself. The conversation is not even about the secret science of the Jedi, but about how not to hit a dear friend in the sandbox with a typewriter on the head and not smash your brand new iPhone against the wall in a fit of anger at your mother. How can we, parents, help ourselves and our children in the difficult but so important science of self-regulation?

How can we, parents, help ourselves and our children in the difficult but so important science of self-regulation?

1. We continue to talk about feelings

We all remember the advice of psychologists that feelings should be named and spoken. And it is true. There are three small aspects that I want to talk about in more detail.

And how many names of feelings and emotions do you usually use in such conversations? ten? twenty? They say there are more than 500 of them. By the age of three, all children distinguish between anger, sadness and joy. But if they do not distinguish between anger, confusion, confusion, embarrassment, fatigue, resentment, disappointment, then all the situations listed above will be recorded as "anger" with the corresponding aggressive reaction of the body and brain.

A study conducted by the University of Washington (Seattle) showed that children with a richer vocabulary of emotions have fewer behavioral problems. It should be taken into account that the word denoting, for example, "disappointment" in the child's head should be associated with a picture, personal experience, a story told and a situation. Such a science seems complicated only at first glance. To get started, write down 10-15 different words for feelings on a piece of paper and write a story for each of them. Or buy a book in which everything has already been thought up before you.

Such a science seems complicated only at first glance. To get started, write down 10-15 different words for feelings on a piece of paper and write a story for each of them. Or buy a book in which everything has already been thought up before you.

Another trap - we were taught to "pronounce emotions", but forgot to say that there are also a lot of positive emotions in the world. As a result, mother often diligently tells her son that he was upset, angry, disappointed ... But for some reason she does not say: “Oh! It looks like you are so proud that you were able to run first! I know this feeling! It lives somewhere in my solar plexus! High five!" or “Yes, you are all glowing with the joy of meeting your beloved friend”, “You smile so broadly when you come from school, you must have come up with a new prank that amused you so much! Will you share?"

Talk about the good, the good, the bright. Unnatural? No, it's just a little weird. But habits can be changed

And the third thing to tell a child about emotions is that they change. It doesn’t mean that a person who has lost his beloved knife, for which he has been saving for the last three years, should say: “It’s nothing, it’s a matter of life!”. We will definitely share his feelings: we will become a vest, a container, what mom and dad are supposed to become. But if in the morning everything was terrible - you wanted to sleep, it was raining and treasures were lost from your pocket - and in the afternoon someone skips running towards you, you can remind: “Oh! You were so sad in the morning because it was raining and you found out that you had lost your math notebook and your only friend in class was sick, it's a very unpleasant state, but look - you're having fun now!

It doesn’t mean that a person who has lost his beloved knife, for which he has been saving for the last three years, should say: “It’s nothing, it’s a matter of life!”. We will definitely share his feelings: we will become a vest, a container, what mom and dad are supposed to become. But if in the morning everything was terrible - you wanted to sleep, it was raining and treasures were lost from your pocket - and in the afternoon someone skips running towards you, you can remind: “Oh! You were so sad in the morning because it was raining and you found out that you had lost your math notebook and your only friend in class was sick, it's a very unpleasant state, but look - you're having fun now!

The next step is to help the child understand why his emotions and feelings change. What helps him? To be alone? Read? Hug with mom? You need to talk about emotions, using as many different words as possible, talk about positive experiences, remember the precepts of King Solomon (“everything passes”) and try to show how feelings succeed each other.

2. There is a time and a place for everything

The usual picture on the playground: the sun is shining, the boy is building a city out of sand, the mother is enjoying a warm day and a blessed picture. And suddenly another child appears in the sandbox, who, without any bad thought, touches the newly built tower with his foot, it collapses - and your so calm boy with a furious cry rushes at the offender.

For some reason, many adults consider this moment to be a good occasion for politeness lessons. Yes, you need to interfere, but not educate! All these correct words, about “we need to share”, “we are people - we don’t fight, we talk”, “apologize to the boy, you hit him” do not work now. And even harm. All you can do is physically stop, voice emotions, name the condition, apologize to the victims (on your own), if any, and get out of the situation.

You can stop at the suppression of the conflict. All discussions after and preferably in private. Use active listening

“What happened to you? I think you are angry? Oh, I can imagine how angry I would be if someone destroyed the results of my work! And where was this anger born? In the chest? In a stomach?". Empathize: “It was terrible, I can’t even imagine how upset I would be.” And then try to develop behavior strategies. How not to let anger control you? And what could be done? What do people generally do in such situations? They definitely don't hit, we're talking. It is important to remember: any feelings and thoughts are acceptable, but not any behavior.

3. Take care of yourself

The fuel for the fire of hysteria is emotions. Therefore, it is very important to determine where your trigger is, your red button. Children are very talented in determining what exactly pisses off the mother-educator-teacher the most. Maybe you are annoyed by screaming or whining, or obscene language from the lips of a five-year-old angel, you can’t stand it when they spit or bite, run away in the other direction or break everything? What actions of the child in your brain suddenly lights up in red letters: “That’s what I definitely can never allow. Because!".

Our task is to cancel these letters and understand that such behavior is a challenge, but not a struggle. This is just a parental, human task - not to react, not to lose control, not to fall into the state of a child. Stay mature and responsible. You should first understand what your personal reaction includes, name this behavior, wait for it and next time take it as a signal in order to smile to yourself and say: “Well, no, brother, today you won’t take me with some kind of insults to all our ancestors until the fifth knees." How to do it? Inhale-exhale three times (we inhale - we smell the flowers, we exhale - we blow out the candle), relax your shoulders and lips, say to yourself: “This is my son. He is bad now. I love him. I can stay calm and help." And if everything worked out, praise yourself very much.

This is just a parental, human task - not to react, not to lose control, not to fall into the state of a child. Stay mature and responsible. You should first understand what your personal reaction includes, name this behavior, wait for it and next time take it as a signal in order to smile to yourself and say: “Well, no, brother, today you won’t take me with some kind of insults to all our ancestors until the fifth knees." How to do it? Inhale-exhale three times (we inhale - we smell the flowers, we exhale - we blow out the candle), relax your shoulders and lips, say to yourself: “This is my son. He is bad now. I love him. I can stay calm and help." And if everything worked out, praise yourself very much.

It's not so easy to do it differently, not to follow the feelings. But staying calm is not always enough.

We can't "just ignore the child's unwanted behavior"

What if he runs under a car or tries to smash a store window with his head, or just hits all the children around him? Of course, we do not ignore. We stop actions that may be hazardous to health, if necessary, we take the child out of the situation. But at the same time, we remain calm and ready to help - they really feel very bad. We are ready to hug, give a handkerchief, water, talk. And we don't care that there are a lot of reproachful looks around. After all, we remember that a tantrum is a sign that a child needs our help. For example, to teach a new model of behavior.

We stop actions that may be hazardous to health, if necessary, we take the child out of the situation. But at the same time, we remain calm and ready to help - they really feel very bad. We are ready to hug, give a handkerchief, water, talk. And we don't care that there are a lot of reproachful looks around. After all, we remember that a tantrum is a sign that a child needs our help. For example, to teach a new model of behavior.

4. Forewarned is forearmed

It is easy to advise to "stay calm", but sometimes it is almost impossible to implement this advice. But being ready for a challenge makes us stronger. Watch the child. On average, in children under three years of age, tantrums (sometimes short-term, like summer rain) happen once or twice a week. Enough to accumulate material for analysis.

What triggers your child's temper tantrum? Look for the trigger

Does he hate being told no, or is he sensitive to things and hates to be touched? Does he need a particularly large personal space, is he sensitive to loud sounds? Afraid of dogs? Discuss this feature with everyone who communicates with the child, perhaps their observations will help you learn something new. And be prepared to face the storm every time this trigger sets off a tantrum mechanism for your son and daughter. Remember, it's just a task. And yes, everything will pass.

And be prepared to face the storm every time this trigger sets off a tantrum mechanism for your son and daughter. Remember, it's just a task. And yes, everything will pass.

5. Everything has a purpose, and children's tantrums too

It is useful to understand what that purpose is. All goals can be divided into two types: avoid something (action, person, event, space, process) or get something (thing, help, attention, power, communication). It is important that hysteria does not become a really working tool, that its consequence is not the achievement of a goal. In addition, sometimes you can avoid crying and arguing by simply not doing what causes such a reaction.

The method of “natural consequences” works best, not punishment by mom or dad, since they have authority and the right “given from above”, but quite natural and not quite pleasant consequences. Sobbed in the store - they couldn't buy something. I had a fight on the playground - I had to leave from there, threw a book - I couldn’t read at night. Mom’s bad mood also refers to “natural consequences”.

Mom’s bad mood also refers to “natural consequences”.

6. Always be on the side of the child

Against whom? Against tantrums. Unfortunately, they do not always end in four years. At some point, the child himself understands that such behavior does not lead to anything good for him. It bothers him. How? For example, it makes family evenings sad, spoils relations with dad, does not allow making friends. There can be many examples.

There is a strategy for dealing with unacceptable behavior by children. Yes, you can be unbearable, but I still love you and accept even this. In this position, you are a noble suffering mother, and he is a little tormentor. It is hard to be a tormentor of such a beautiful-hearted person, it is so easy to get to feelings of guilt, and then to aggression, fleeing from guilt.

It is better to choose a scheme in which you are together. Tell your son, look, something is attacking you and seriously ruining our lives. I agree?

What do you think it is? What's his name? What does he want? And how to deal with it? At the same time, you will be able to analyze how outbursts of anger arise and what really helps to stop them. You can read more about this approach in Michael White's book Narrative Practice Maps.

You can read more about this approach in Michael White's book Narrative Practice Maps.

7. Look for compromises

Very many people do not tolerate categorical prohibitions and demands. It often happens that children grow up, and we do not have time to readjust, and still discuss the issue of a hat or a first for lunch with a 15-year-old daughter. The “offer a choice” strategy works in many cases. With three-year-olds, the choice even works at the level of what you will have for lunch: buckwheat or rice. But closer to the first anniversary, sometimes you have to agree together on how to spend the weekend, or on the amount of time devoted to computer games.

There are three types of behavior. You can insist on your own. From "it will be so because I said so" to "well, you yourself understand that this is the right decision, because ...". You can give up under an avalanche of children's tears and screams, admit that you have not been able to manage processes for a long time, and give everything to the will of the child. Now such parents are becoming more and more common. You can also prefer the path of agreements and compromises - it is longer and more difficult, but in the end it makes all the participants in the negotiations stronger. What does it mean? To try together to find a way out acceptable to all parties. In this regard, it is easy to run into pitfalls.

Now such parents are becoming more and more common. You can also prefer the path of agreements and compromises - it is longer and more difficult, but in the end it makes all the participants in the negotiations stronger. What does it mean? To try together to find a way out acceptable to all parties. In this regard, it is easy to run into pitfalls.

Sometimes an attempt to "negotiate" becomes a manipulation of the "I said so" plan - the goal is to convince that I offer the right solution walls in your nursery. Or honestly look for a way out.

How to test yourself? It's very simple - if you already know the "correct answer" when you start looking for a compromise, this is not a compromise. Ideas should be born and discussed in the course of the conversation. You can read more about how to learn to compromise in your family in the book The Explosive Child by Green Ross.

8. Technologies for controlling your emotions

Even the simple rule of three breaths sometimes works.