How many child soldiers are there in colombia

Refworld | Child Soldiers Global Report 2001

REPUBLIC OF COLOMBIA

Mainly covers the period June 1998 to April 2001 as well as including some earlier information.

- Population:

– Total: 41,564,000

– Under-18s: 16,235,000 - Government armed forces:

– Active: 153,000

– Reserves: 60,700 - Paramilitary: 95,000

- Compulsory recruitment age: 18

- Voluntary recruitment age: 18

- Voting age (government elections): 18

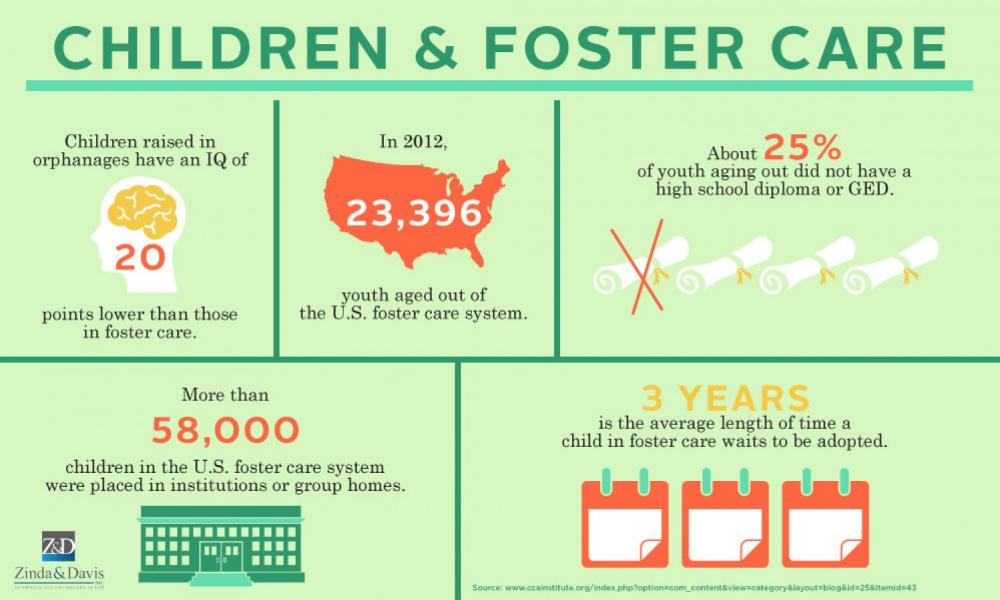

- Child soldiers: indicated in armed opposition groups and paramilitaries – estimated number 14,000410

- CRC-OP-AC: signed 6 September 2000, supports "straight-18" position

- Other treaties ratified: CRC; GC/AP/I+II

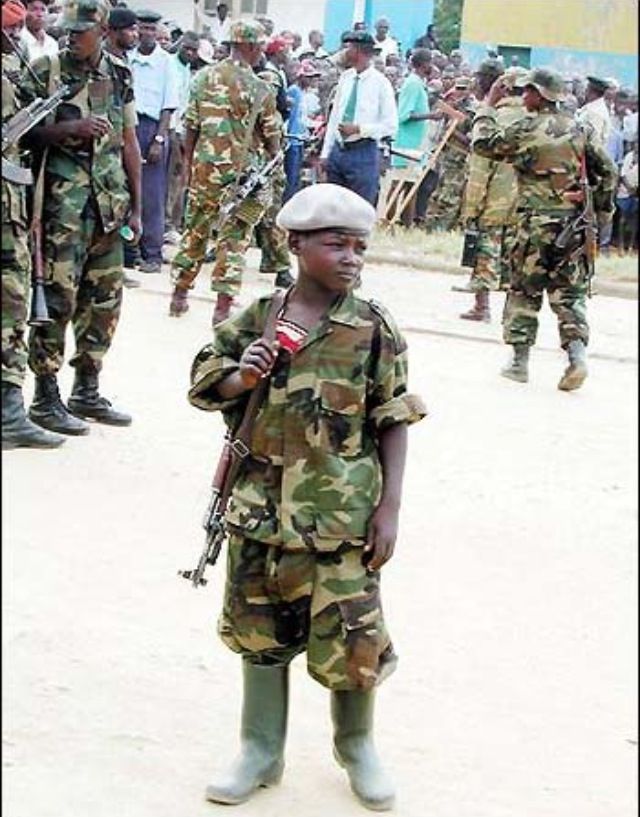

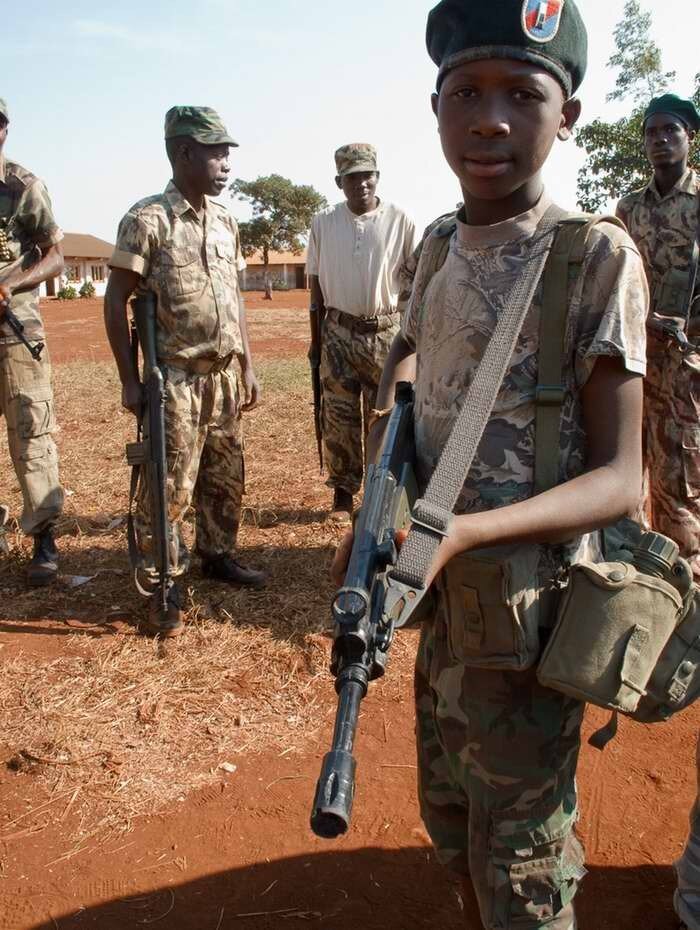

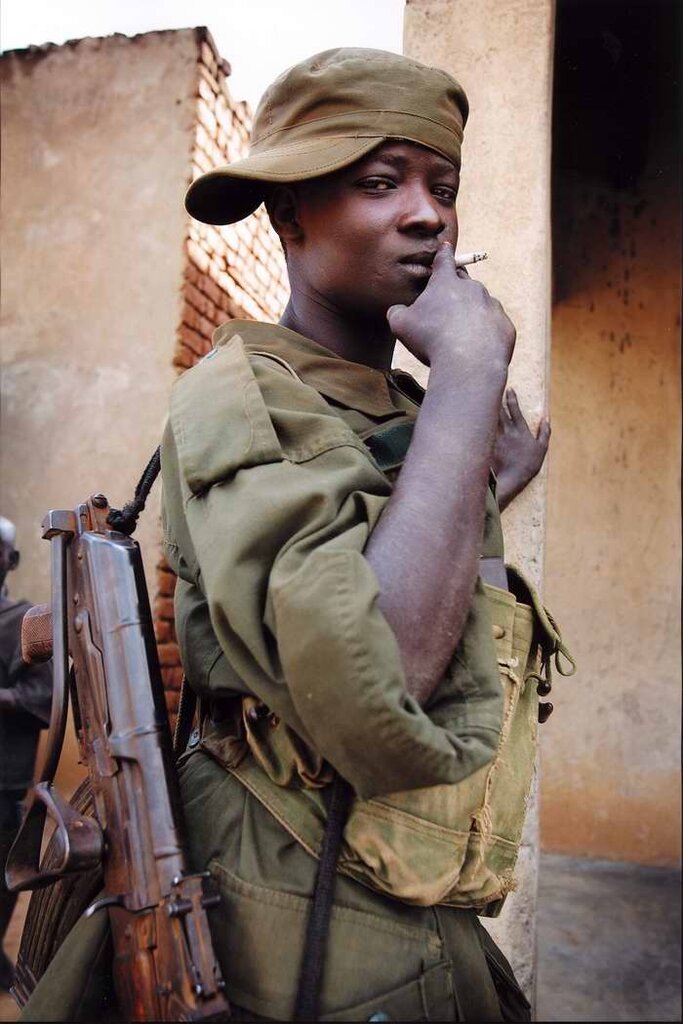

- Children as young as eight-years-old are fighting with guerrilla and paramilitary groups in Colombia. Children are often recruited forcibly and face harsh punishments, including death if they attempt to desert.

The government has ended the recruitment of under-18s and demobilised those remaining in its armed forces, but continues to enlist students in military schools from age 15.

CONTEXT

Armed conflict has been ongoing for almost 50 years involving government armed forces, guerrillas since the 1960s, and paramilitary groups originally set up by the government during the 1980s and now tacitly supported. The conflict is related to land and control of coca, mining and oil resources. All sides in the conflict have committed human rights abuses and political violence has increased dramatically in the country. The main armed opposition group, Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC (Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia), controls the despeje, a zone the size of Switzerland from which the military has withdrawn. Peace talks continue between the government and the FARC but have yet to yield any concrete advances. Despite efforts to resume negotiations between the ELN and government, obstacles still remain.

In 2000, the Colombian government launched a six-year plan for 'Peace, Prosperity and Strengthening of the State' known as 'Plan Colombia'. The US government pledged a multi-billion dollar military assistance package in support. There are grave concerns, both within and outside Colombia, that Plan Colombia may lead to an increase in human rights violations, including child recruitment.

GOVERNMENT

National Recruitment Legislation

Article 216 of the 1991 Constitution states that: "All Colombian citizens are obliged to take up arms when public need mandates it in order to defend national independence and the public institutions. The law will determine the conditions which at all times qualify an individual for exemption from military service and the benefits for service in them".411

According to Law 48/93, "All Colombian men are obliged to define their military situation from the date they achieve the majority of age, with the exception of the students of the "bachillerato" (baccalaureate), who will define when they obtain their school baccalaureate certificate. The military obligations of Colombians end when they turn 50" (article 10).412

The military obligations of Colombians end when they turn 50" (article 10).412

On 23 December 1999, the government adopted Law 548 amending Law 418 of 1997 to establish that "Those below the age of 18 will not be incorporated into the ranks to serve military service. The incorporation of students of eleventh grade, below this age that, according to Law 48 of 1993, should be chosen to serve such service, will be postponed until they reach the referred age." (Article 2)413 This was reinforced by internal police Instructivo No. 8 of January 19 2000 which stated that: "no minors will be incorporated for the military service in the National Police".414

Bachillerato students are able to choose to do the military service when they turn 18 or when they finish their studies, subject to proof that they are attached to a university (Law 548 of 1999 and law 642 of 2001).415 The law that regulates this issue establishes different modes of military service, according to the number of places and the needs of the forces: "bachiller soldier", 12 months; regular soldier, between 12 and 24 months; auxiliary of "bachiller soldier", 12 months. 416

416

Article 14 of Law 418, known as "Public Order" ( Ley de Orden Público) , approved by the President on 26 December 1997 criminalises the recruitment of under-18s as follows: "Any person who recruits minors as members of rebel or self-defence groups, forces them to join such groups or receives them into such groups and any persons who give them military training for that purpose shall be liable to three to five years' imprisonment. Members of outlaw armed organizations who recruit young persons under eighteen (18) years of age into said organizations shall not be entitled to the legal benefits for which this Act provides."417 Law 418 also established that minors (less than 18 years old) should not join the army even on a voluntary basis.418

National Recruitment Practice

Before December 2000, approximately 16,000 under-18s were part of the Colombian armed forces. After protests from relatives, the government said under-18s would only be assigned office duties and only sent to conflict areas once they had turned 18. This was not always observed, however, and youths were still at risk since they were considered legitimate military targets by remaining in military installations and wearing military uniforms. There were also reports of ill-treatment of bachilleres.

This was not always observed, however, and youths were still at risk since they were considered legitimate military targets by remaining in military installations and wearing military uniforms. There were also reports of ill-treatment of bachilleres.

On 20 December 1999, the Colombian Army discharged 618 persons under the age of 18 from the Army and more than 200 others from other forces. After Law 548 was adopted, there have been two incorporations of auxiliary "bachilleres", but none of these included people under the age of 18.419

Military Training and Military Schools

In 2000, there were officially 32 military schools in Colombia. While the majority of military schools set a 18 as the minimum age of entry, the minimum age for the 2001 intake for sub-officer training is 17 and officer training is 15.420 The minimum age to join the Escuela Militar de Cadetes General José María Córdova (Military Cadets School General José María Córdova) is 15 years of age. 421 To join the Escuela Naval Almirante Padilla as a cadet the minimum age is 16.422 No information was available regarding the number of under-18s currently enrolled in such programs or whether they are members of the armed forces.

421 To join the Escuela Naval Almirante Padilla as a cadet the minimum age is 16.422 No information was available regarding the number of under-18s currently enrolled in such programs or whether they are members of the armed forces.

CHILD RECRUITMENT BY ARMED GROUPS

Children as young as 8 of both sexes are currently fighting as soldiers in the Colombian conflict.423 They are recruited, often forcibly, into the ranks of armed groups, paramilitaries and militias. Children under the age of 18 are used for many different tasks, including as combatants, for kidnapping, guarding hostages, as human shields, messengers, spies, sexual partners and as "mules" to transport arms and place bombs.424 It is likely that many of these children are also active in the production of coca, given the close links between groups that use children and the drug trade.425

The guerrillas refer to child soldiers as "little bees" for their agility and power to sting; the paramilitaries as "little bells" because they are deployed in front to draw fire, detect traps and serve as an early warning system. In the cities, child members of militias are called "little carts" because they ferry drugs and weapons without raising suspicion.

In the cities, child members of militias are called "little carts" because they ferry drugs and weapons without raising suspicion.

Armed opposition groups are estimated to include 4,000 children below the age of 18, with a third of them estimated to be girls. Right-wing paramilitaries and militias are estimated to include 3,000 children, some as young as eight years old. Urban militias, linked to various parties to the armed conflict are estimated to include approximately 7,000 children below 18 years of age.426 According to UNICEF's Colombia office, 80 % of the new armed groups' fronts are made up of women and children.427 In what is a worrying trend, increasing numbers of child soldiers are being "born into" armed groups because their parents are members. According to the People's Ombudsman Office, 20 per cent of all Colombian children directly or indirectly participate in the armed conflict.428

Between 1 January and 27 April 2001, the Colombian Army reported 53 cases of child soldiers; 24 were captured during military operations, while 29 were deserters; of these 19 were girls and 34 boys. 429

429

In rural areas, families caught in the cross-fire often are forced to offer their children to guerrilla units in order to survive.430 In many areas children are taken by armed groups or paramilitaries as part or in lieu of taxes families must pay.431 According to press reports, families from the despeje, as well as from Arauca, Valle del Cauca, and Antioquia departments have fled their homes because guerrilla groups have tried to recruit their children forcibly. On 4 May 2000, a woman from Norte de Santander department, with the help of the Colombian military, delivered her 12-year-old son to the ICBF to protect him from the FARC, which was trying to recruit him forcibly.432

There are also many cases of so-called "voluntary" recruitment given the lack of other education and employment opportunities for boys and girls. Many join the guerillas, but mostly paramilitary groups, because they are promised a wage. Sometimes runaways join the armed groups as a result of family violence or losses; others want to 'defend' their families against attacks from the paramilitary.433 Interviews carried out with girl combatants who left armed groups during the 1990s indicate that they joined because they fell in love with guerrilla boys.434

Sometimes runaways join the armed groups as a result of family violence or losses; others want to 'defend' their families against attacks from the paramilitary.433 Interviews carried out with girl combatants who left armed groups during the 1990s indicate that they joined because they fell in love with guerrilla boys.434

Child combatants receive comprehensive though rapid military training (including in the use of weapons, manufacture of bombs and military strategy). Child soldiers are virtual prisoners of their commanders; punishments for infractions are often extremely harsh and sometimes involve death.

According to numerous reports, girls are frequently subjected to sexual abuse.435 The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has received reports of sexual abuse of girls serving in the ranks of the guerrillas and paramilitaries, generally by middle-ranking officers.436 The FARC operates a "sexual freedom" policy and there are reports of young girls being fitted with intra-uterine devices or given contraceptive injections. In one case a fifteen-year-old combatant who was killed was found to be pregnant.437 Cases of sexual slavery are common. The Roman Catholic Church documented one case of a 13-year-old girl who was recruited by the guerrillas and used for sex before a nun persuaded them to release her.438 Adolescent girls are often recruited for special missions, which involve them being forced to have sexual relations with government soldiers in order to get information from them.439

In one case a fifteen-year-old combatant who was killed was found to be pregnant.437 Cases of sexual slavery are common. The Roman Catholic Church documented one case of a 13-year-old girl who was recruited by the guerrillas and used for sex before a nun persuaded them to release her.438 Adolescent girls are often recruited for special missions, which involve them being forced to have sexual relations with government soldiers in order to get information from them.439

Reports indicate that there was an increase in children abandoning the ranks of the guerrillas during 2000 at great peril to their lives.440 Runaways are considered deserters and are often executed on the spot by the FARC and ELN.

Government Treatment of Suspected Child Soldiers

Colombia does not have legislation affording special legal status or treatment to child soldiers. Juvenile deserters and those who are captured are considered criminals. 441 Children who are captured or surrender are sent for trial before a juvenile judge or to a judge ascribed to institutions for juvenile offenders.

441 Children who are captured or surrender are sent for trial before a juvenile judge or to a judge ascribed to institutions for juvenile offenders.

According to information obtained by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, surrendered or captured child soldiers are often incorporated into the armed forces or detained in military installations instead of being presented before a judge to be tried. They often remain in uniform in military bases.442 The armed forces have forced former child guerrillas to appear before the press and to make statements, prepared by the armed forces, in order to discredit the guerrillas.443 There are also reports of the Army forcing captured child soldiers to find and deactivate landmines laid by armed groups, or to act as informants and guides.444

The Government's Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (Family Welfare Institute) opened the first home for former child soldiers in 2000. 445 Places in these programs, however, are extremely limited and the majority of former child soldiers are placed with hardened juvenile delinquents in camps.

445 Places in these programs, however, are extremely limited and the majority of former child soldiers are placed with hardened juvenile delinquents in camps.

The People's Ombudsman Office indicated that between 1994 and 1996, 13 per cent of children who have been placed in such detention centres were killed by fellow inmates.446 Due to the security risks faced by former child soldiers, the locations of many re-integration programs are kept secret and many children change their name. This often leads to long delays before they can return to their families, if at all.

The involvement of children as combatants in the conflict has also placed other children at risk. On 15 August 2000, for instance, an army unit near Pueblo Rico, Antioquia, mistook a party of schoolchildren for a guerrilla unit and opened fire, killing six children aged between 6 and 10, and wounding six others.447

OPPOSITION

Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)

The Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) is the largest armed group in the country. It was established in the mid-1960s and originally espoused a Marxist ideology. The FARC advocates widespread reforms and re-distribution of wealth as outlined in its 10-point program.448 A large percentage of the FARC's income is derived from "taxes" imposed on drug operations in FARC-controlled regions, as well as kidnapping and extortion.449

It was established in the mid-1960s and originally espoused a Marxist ideology. The FARC advocates widespread reforms and re-distribution of wealth as outlined in its 10-point program.448 A large percentage of the FARC's income is derived from "taxes" imposed on drug operations in FARC-controlled regions, as well as kidnapping and extortion.449

In June 1999, the FARC pledged to the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict not to recruit children below the age of 15.450 More recently it has stated publicly that it does not recruit anyone under the age of 15 and that youngsters who have joined themselves are returned to their families.451

According to press reports, in April 2000 FARC military commander Jorge Briceño Suarez admitted that the FARC made regular use of child combatants.452 FARC leader, Manuel "Sure shot" Marulanda, told reporters when asked about calls for the group to stop enlisting minors: "They're going to stay in the ranks". 453

453

The FARC reportedly announced in 2000 that all persons between the ages of 13 and 60 in the despeje zone are liable for military service with the guerrillas; families fleeing the zone reported that they were asked to surrender children to the FARC as of their 14th birthday. The Roman Catholic church reported that the FARC lured or forced hundreds of children into its ranks in the despeje zone and other areas under its control.454

In June 2000 the FARC reportedly recruited at least 37 youths, including minors, in the municipality of Puerto Rico in southern Meta department. According to one NGO, in Putumayo the FARC instigated compulsory service of males between the ages of 13 and 15 and was recruiting in high schools.455

The Colombia Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights continued to receive complaints during 2000 of the FARC continuing to recruit children under 15 years of age.456 The FARC persisted in this practice, in violation of their internal rules and in spite of the fact that they returned some children to their families in the despeje zone. 457 Eight FARC guerrillas, all estimated to be between the ages of 13 and 15, were killed during a January 2000 attack on the town of El Castillo, Meta department.458 Footage of FARC child soldiers, in what is believed to be a training video, were aired on Colombian television in May 2001. The footage shows guerrillas, some as young as 11 making missiles and digging mass graves for dead guerrillas.459 In August 2000 members of the FARC reportedly killed a school rector in Meta department for criticizing the recruitment of his students.460

457 Eight FARC guerrillas, all estimated to be between the ages of 13 and 15, were killed during a January 2000 attack on the town of El Castillo, Meta department.458 Footage of FARC child soldiers, in what is believed to be a training video, were aired on Colombian television in May 2001. The footage shows guerrillas, some as young as 11 making missiles and digging mass graves for dead guerrillas.459 In August 2000 members of the FARC reportedly killed a school rector in Meta department for criticizing the recruitment of his students.460

The FARC is also known for recruiting children in Venezuela where it conducts some activities. Parents have reportedly been paid US$600 a month for the recruitment of their child. In October 2000, Luz Celeste Gonzalez Aguilar, a 16-year-old Venezuelan national, surrendered to the Colombian Army after 6 years with the FARC. She confirmed reports of FARC recruitment of under-18 Venezuelan children. 461 She had been serving with other Venezuelan youths under the age of 18, who had been recruited by a network operating in Venezuela.462

461 She had been serving with other Venezuelan youths under the age of 18, who had been recruited by a network operating in Venezuela.462

FARC activities have been reported also in Bolivia, Ecuador and Panama. There are concerns that the armed group might also recruit children from those countries or Colombian children displaced to other regions.

National Liberation Army (ELN)

The Ejército Nacional De Liberación – ELN (National Liberation Army) is the second largest guerilla group in Colombia. In 1987, it joined the FARC and other guerrilla groups to form a joint front called Coordinador Guerrillera Simón Bolivar.

On 15 June 1998, the ELN signed the Mainz "Heaven's Gate" agreement in which it committed itself not to recruit anyone under the age of 16 into its ranks.463 There are, however, consistent reports that the ELN continues to recruit children under the age of 15 into its ranks. In one earlier case from October 1997, the ELN attempted to use a nine-year-old child to deliver a bomb to a polling place in Cucuta.464

In one earlier case from October 1997, the ELN attempted to use a nine-year-old child to deliver a bomb to a polling place in Cucuta.464

PARAMILITARIES

The Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC (United Self-Defence Groups of Colombia) is a right-wing paramilitary umbrella organization. It was formed in the early 1980s in response to kidnappings by guerrilla groups. Human rights activists claim the paramilitaries are responsible for most of the human rights abuses committed in Colombia. The paramilitaries allegedly fund their actions from the cultivation and trafficking of drugs.465

Although the Colombian government denies any links with paramilitary groups, numerous reports continue to be received of state officials directly participating in or turning a blind eye to paramilitary activities.466

Various sources indicate that 15 per cent of paramilitary groups are under 18 and in certain areas up to 50 per cent of some paramilitary units are children. Children as young as eight have been seen on patrol with paramilitaries.467

Children as young as eight have been seen on patrol with paramilitaries.467

Paramilitary groups are reported to have resorted to forced recruitment. In May 2000, the Autodefensas Unidas del Sur del Casanare circulated leaflets in the rural area of Monterrey (Casanare) calling up young people living in the region for "compulsory military service". In October 2000, paramilitaries took away several youths in Puerto Gaitán (Meta) by force for military training468

Paramilitaries consider service compulsory for as long as two years. Families who refuse risk being considered sympathetic to armed opposition groups and attacked. According to the People's Ombudsman Office, girls are at particular risk, and a high level of sexual abuses by adult paramilitaries has been reported.469

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights received reports of paramilitary groups offering money to children in poor neighborhoods or internally displaced camps to entice children to join their ranks. On 25 March 1998, journalists reported seeing a group of over 50 students, including 10 girls, leave their town to join the paramilitaries, tempted by the salaries they were offering despite attempts by fellow students and community leaders to dissuade them.470 In September 1997 members of the Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urbá (ACCU) – part of the AUC umbrella group – recruited 50 under-18s during a single day by offering them money in Policarpa neighbourhood of Apartadó, Antioquia.

On 25 March 1998, journalists reported seeing a group of over 50 students, including 10 girls, leave their town to join the paramilitaries, tempted by the salaries they were offering despite attempts by fellow students and community leaders to dissuade them.470 In September 1997 members of the Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urbá (ACCU) – part of the AUC umbrella group – recruited 50 under-18s during a single day by offering them money in Policarpa neighbourhood of Apartadó, Antioquia.

MILITIAS

Urban militias emerged in Colombia in the 1980s. Some militias were independent and others received training and weapons from armed opposition or paramilitary groups.471 Indigenous people and Afro-descendants have been pressured by guerilla groups to form militias in areas previously under their control but re-taken by paramilitary groups, particularly in Valle and Cauca Departments.

It is estimated that some militia groups are comprised of 85 per cent children, a high proportion of these being kidnap victims. 472

472

Militias are considered as good training grounds for future combatants473 and have been targeted as such by opposing groups.

DEVELOPMENTS

Prevention and demobilization programs

In 1999, the ICBF established a special program to deal with the re-integration of former child combatants who have escaped or been captured. In addition, several other independent re-integration programs (for example, Alborada de Vida, Don Bosco) operate throughout the country. AFSC "Comite Andino de Servicios", the Colombian Program of Catholic Relief Services, and the Diocese of Granada are jointly undertaking a program of prevention and protection of children in the demilitarised zones.

High-level visits

The Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, Mr Olara Otunnu, visited Colombia in June 1999. Government officials announced their intention to stop enlisting under-18s and the FARC committed itself not to recruit children under the age of 15. During his visit Mr Otunnu tried to ensure that "the protection and welfare of children are placed prominently on the peace agenda".474 The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights visited Colombia in December 2000. Her report to the 57th Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights called on all armed and paramilitary groups to stop the recruitment of children and demobilise those in their ranks.475

During his visit Mr Otunnu tried to ensure that "the protection and welfare of children are placed prominently on the peace agenda".474 The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights visited Colombia in December 2000. Her report to the 57th Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights called on all armed and paramilitary groups to stop the recruitment of children and demobilise those in their ranks.475

International standards

Colombia signed the CRC-OP-AC on 6 September 2000 and upholds the "straight-18" position.

When Colombia signed the Convention on the Rights of the Child in January 1990 government made a declaration in which it considered that "while the minimum age of 15 years for taking part in armed conflicts, set forth in article 38 of the Convention, is the outcome of serious negotiations which reflect various legal, political and cultural systems in the world, it would have been preferable to fix that age at 18 years in accordance with the principles and norms prevailing in various regions and countries, including Colombia, for which reason the government, for the purposes of article 38 of the Convention, shall construe the age in question to be 18 years". The declaration referred only to "taking part in armed conflict" and did not mention recruitment. In depositing its instrument of ratification of the Convention in January 1991, the government entered a reservation to the provisions of these paragraphs, stating that the age referred to should be understood to be 18 years. When it withdrew its reservation on 26 June 1996, the Government of Colombia issued a political declaration stating that it would refrain from recruiting young people below the age of 18 into its armed forces or police for the purpose of taking a direct part in hostilities. In view of the declaration made when the reservation to the Convention was withdrawn, articles 13 (no longer valid) and 14 were added to Law 418.

The declaration referred only to "taking part in armed conflict" and did not mention recruitment. In depositing its instrument of ratification of the Convention in January 1991, the government entered a reservation to the provisions of these paragraphs, stating that the age referred to should be understood to be 18 years. When it withdrew its reservation on 26 June 1996, the Government of Colombia issued a political declaration stating that it would refrain from recruiting young people below the age of 18 into its armed forces or police for the purpose of taking a direct part in hostilities. In view of the declaration made when the reservation to the Convention was withdrawn, articles 13 (no longer valid) and 14 were added to Law 418.

410 http://www.rb.se.

411 http://www.georgetown.edu/LatAmerPolitical/Constitutions/Colombia/colombia.html.

412 http://www.mindefensa.gov.co/ini_frames.asp?cod_modulo'2, Ministerio de Defensa Nacional Colombiana.

413 Ley No. 548 del 23 de dicimbre de 1999.

414 Information provided by fax by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia to the CSC on the 2/03/01.

415 "Los jovenes bachilleres podran optar por prestar su servicio militar al cumplimiento de su mayoria de edad o cuando culminen sus estudios superiores, siempre que demuestren estar vinculados a un centro de educacion superior o tecnologico; de acuerdo a lo ordenado en la ley 548 de 1999 y la ley 642 de 2001."

416 http://www.reclutamiento.mil.co/obligatorio/index.htm, Republica de Colombia, Ministerio de Defensa, Ejercito Nacional de Colombia, Direccion de Reclutamiento y Control de Reservas.

417 CRC/C/70/Add.5, 5/01/00 , paragraphs 409-419.

418 Boletin de Prensa "El Ejercito colombiano licencia a todos los menores de 18 anos de us filas", Unicef Colombia, 20/12/99. See also newspaper article: "Yo queria seguir en el ejercito".

419 Information provided by fax by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia to the CSC on the 2/03/01.

420 http://www.reclutamiento.mil.co/incorporaciones/body.htm.

421 http://www.esmic.edu.co/ingreso.htm.

422 http://sirius.enap.edu.co/infoingr.htm.

423 Tercer Informe sobre la Situacion de los Derechos Humanos en Colomba, Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Organizacion de los Estados Americanos, OEA/Ser.L/V/II/102, 26 February 1999. See also: Salazar, Maria Cristina, "Consequences of armed conflict and internal displacement for children in Colombia,. Winnipeg Conference on War Affected Children, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Colombia, E/CN.4/2001/15, 8/02/01, and US State Department Report 2000.

424 Tercer Informe sobre la Situacion de los Derechos Humanos en Colomba, Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Organizacion de los Estados Americanos, OEA/Ser.L/V/II/102, 26/02/99. See also study be Defensoria del Pueblo, 1996-1998.

425 See: La Semana "Soldaditos de plomo,. 17-24 November 1997.

17-24 November 1997.

426 http://www.rb.se, these figures have also been confirmed by reliable sources within Colombia who have asked to remain anonymous for security reasons.

427 El Tiempo, "Me ensenaron a manejar armas en tres dias", 4 December 2000.

428 Statement of the People's Advocate to the Latin American and Caribbean Conference on the Use of Children as Soldiers, Montevideo, Uruguay, 5-7 July 1999.

429 No cesa violencia contra los ninos de Colombia, 27/04/01. http://www.ejercito.mil.co/Document/SubOptionNo32/dihsp.htm.

430 "Rights-Colombia: Children of War", IPS, 12/03/99.

431 The Christian Science Monitor, Howard LaFranchi, "When war veterans are children,. 30/03/00.

432 US State Department Report 2000.

433 Salazar, Maria Cristina, "Consequences of armed conflict and internal displacement for children in Colombia,. Winnipeg Conference on War Affected Children.

434 Ibid.

435 See: US State Department Report 1997; See also: Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Colombia, E/CN.4/2001/15, 8/02/01.

436 Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 8/02/01, op cit.

437 No cesa violencia contra los ninos de Colombia, 27/04/01. http://www.ejercito.mil.co/Document/SubOptionNo32/dihsp.htm.

438 US State Department Report 2000.

439 Miami Herald, Tim Johnson, "Child Soldiers". 23/01/00.

440 Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 8/02/01, op cit.

441 UN Wire, Child Soldiers: Colombia attempts to rehabilitate ex-warriors, 31/03/00.

442 Tercer Informe sobre la Situacion de los Derechos Humanos en Colomba, Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Organizacion de los Estados Americanos, OEA/Ser.L/V/II/102, 26/02/99.

443 HRW, War without Quarter Colombia and Humanitarian Law, New York, 1998.

444 The Independent, Jan McGirk, "Recruits a young as eight fight for Colombian guerrillas", 19/11/99.

445 The Christian Science Monitor, 30/03/00, op cit.

446 HRW, War without Quarter Colombia and Humanitarian Law, New York, 1998.

447 Informe de organismos de Derechos Humanos sobre el crimen contra ninos de Pueblorrico. 15/08/00 (http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/colombia/doc/pueblorrico.html).

448 www.farc-ep.org.

449 Jane's Intelligence Review, June 2000.

450 Special representative of Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict concludes humanitarian mission to Colombia, Press Release HR/4418, 9/06/99.

451 BBC World Service, "Colombian army: FARC uses child soldiers. 1/12/00.

452 US State Department Report 2000.

453 Reuters, "Children .Cannon fodder in Colombia's war", 31/01/00.

454 US State Department Report 2000.

455 Ibid.

456 Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 8/02/01, op cit.

457 Ibid.

458 US State Department Report 2000.

459 The Independent, McGirk, Jan, "Brutality of child army fil shocks Colombia,. 2/05/01.

460 US State Department Report 2000.

461 El Nacional, Delgado, Eleonora "Venezolana desertora de las FARC era espia y experta en explosivos,. 20/10/00.

462 El Nacional, Eleonora Delgado, "15 adolescentes venezolanos militan en las FARC,. 22/10/00.

463 US State Department Report.

464 US State Department Report 1997.

465 Interview by Carlos Castano with magazine "Cambio. reported in http://www.cnn.com.

466 Informe Annual 2000. Comision Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Organizacion de Estados Americanos. OEA/Ser./L/V/II.111, 16/04/01.

467 See: Defensoria del Pueblo, "El conflicto armado en Colombia y los menores de edad, Sistema de seguimiento y vigilancia – La ninez y sus derechos". Boletin 2, May 1996; 106th Congress Report, US Senate, 2nd Session 106 291, 11/05/00; US State Department Report 2000; and The Independent, Jan McGirk, "Recruits a young as eight fight for Colombian guerrillas", 19/11/99.

Boletin 2, May 1996; 106th Congress Report, US Senate, 2nd Session 106 291, 11/05/00; US State Department Report 2000; and The Independent, Jan McGirk, "Recruits a young as eight fight for Colombian guerrillas", 19/11/99.

468 Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 8/02/01, op cit.

469 HRW, War without Quarter Colombia and Humanitarian Law, New York, 1998.

470 El Nuevo Heraldo, Marisol Gomez Giraldo, "Jovenes colombianos son reclutados para combatir guerrilleros", 25/03/98.

471 HRW, "Generation under fire: children and violence in Colombia", New York, 1994.

472 The Independent, Jan McGirk, "Recruits a young as eight fight for Colombian guerrillas", 19/11/99.

473 HRW, War without Quarter Colombia and Humanitarian Law, New York, 1998.

474 Special representative of Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict concludes humanitarian mission to Colombia, Press Release HR/4418, 9/06/99.

475 Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, 8/02/01, op. cit.

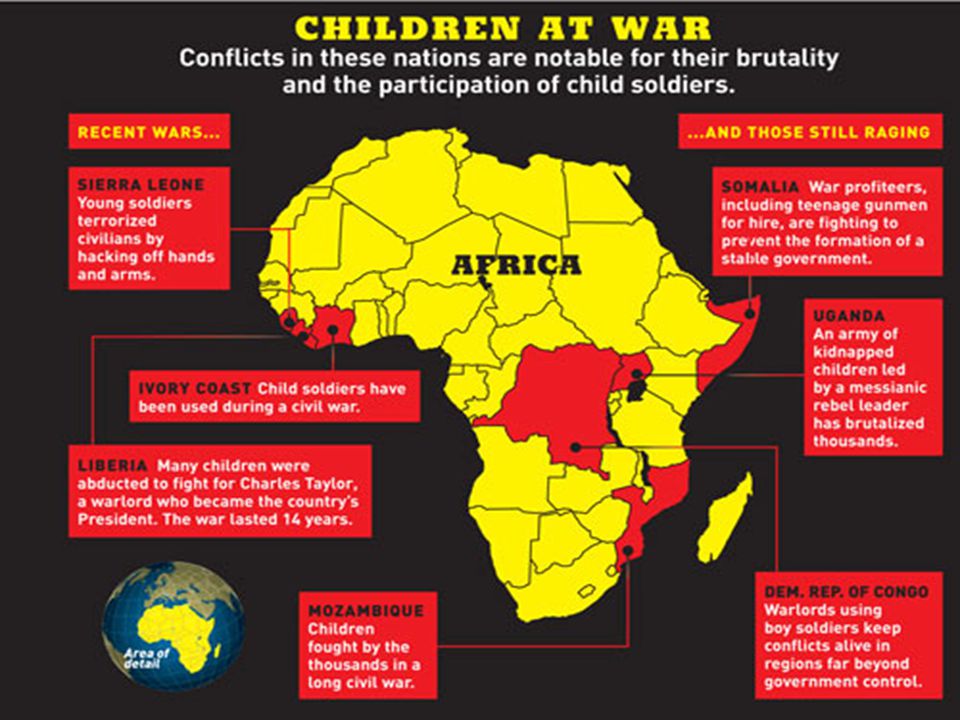

The Struggle of Child Soldiers in Colombia

Child involvement in armed conflict is a harsh reality, although the media often considers it a niche phenomenon with respect to many other international matters. According to estimates, the number of children soldiers around the world today amounts to more than 300,000, but this is only a statistical number. Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Latin America are areas where there is the greatest use of minors in war contexts. The prevalence of child soldiers in Colombia is an issue that requires significant attention.

Child soldiers are often in areas that have very unstable governments and prevalent rebel organizations. Additionally, these areas often implement military investments aimed at maintaining stability at the expense of economic development plans, subsequently leading to other countries cutting them out of international trades. Meanwhile, these governments are frequently unable to deliver even the most essential services resulting in inadequate or absent health care systems, very high levels of unemployment and the lack of education systems. Colombia is no different with a prevalence of unrest and child soldiers.

Meanwhile, these governments are frequently unable to deliver even the most essential services resulting in inadequate or absent health care systems, very high levels of unemployment and the lack of education systems. Colombia is no different with a prevalence of unrest and child soldiers.

The Beginning of Child Warfare in Colombia

The Republic of Colombia stands out in this context not only for having the world’s highest crime levels but also for the increasing rate of children involved in military actions. Guerrilla and paramilitary groups in addition to government armed forces, forcibly recruit children of every age, many as young as 8 years old. Statistics estimate there are up to 14,000 child soldiers now fighting in opposition groups in Colombia; although, it is a practice that has been going on for more than 60 years.

The preferred targets for recruitment are inevitably young people from the poorest neighborhoods of large cities or the more desperate rural areas as they do not have access to basic education and vocational training, and are therefore without many prospects. Furthermore, the recruitment takes place with false promises, but more often through coercion, under the threat of violence to these children and their families. Unfortunately, joining those corps does not represent an escape to the threats for those children that, with little to no training, must act as front liner shields, conduct executions, participate in suicide missions or make and transport explosives. In this context, the gender difference is a thin line and the differences in roles between males and females become smaller and smaller as the age of recruitment falls.

Furthermore, the recruitment takes place with false promises, but more often through coercion, under the threat of violence to these children and their families. Unfortunately, joining those corps does not represent an escape to the threats for those children that, with little to no training, must act as front liner shields, conduct executions, participate in suicide missions or make and transport explosives. In this context, the gender difference is a thin line and the differences in roles between males and females become smaller and smaller as the age of recruitment falls.

According to estimates, female child soldiers make up 40% of the total of child soldiers globally and it seems that militias reserve the hardest tasks for them. Not only do female child soldiers across the world carry out the tasks reserved for boys but many also end up as porters, spies, medical aides and even child brides and sex slaves.

Cause of Child Soldiers

To understand the causes of child soldiers in Colombia, it is necessary to frame the country’s political background. Colombia’s troubled political past dates to 1948 when the murder of liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán caused a war between liberals and conservatives. More than a decade of growing instability led to the establishment of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). Those paramilitary groups later converged in the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) and continued the fights for 20 more years, wreaking havoc and death in the country and kidnapping political leaders. It is among these paramilitary groups that the practice of child exploitation for various purposes began. In conclusion, on June 23, 2016, FARC and the government signed a ceasefire showing commitment to building a better future for Colombia.

Colombia’s troubled political past dates to 1948 when the murder of liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán caused a war between liberals and conservatives. More than a decade of growing instability led to the establishment of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). Those paramilitary groups later converged in the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) and continued the fights for 20 more years, wreaking havoc and death in the country and kidnapping political leaders. It is among these paramilitary groups that the practice of child exploitation for various purposes began. In conclusion, on June 23, 2016, FARC and the government signed a ceasefire showing commitment to building a better future for Colombia.

Five years later, however, political stability still seems far away, and with it, the tragedy of boys and girls used and abused. In November 2019, the Colombian government enforced a national action plan along with other accountability measures like Case No. 07 of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace aimed to prevent recruitment and sexual violence against children in the country. Despite these measures, according to the latest Annual Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, paramilitary groups like FARC continue to forcibly recruit younger boys into their militias without punishment.

07 of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace aimed to prevent recruitment and sexual violence against children in the country. Despite these measures, according to the latest Annual Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, paramilitary groups like FARC continue to forcibly recruit younger boys into their militias without punishment.

Combating the Problem

Luckily, especially in the last decades and thanks to the mobilization of the Colombian government, many nonprofit organizations directly support the cause against child soldiers in Colombia and multiple other poor countries. The way they are doing this is by not only granting populations access to essential services but also by building playgrounds and schools and promoting access to work. One organization that is helping children is Misiones Salesians, which began in Madrid in the 1970s and has reached 130 countries today. It provides international aid to promote the economic and social progress of various countries, thus contributing to eradicating the root causes at the base of child exploitation. Furthermore, Missioni Don Bosco Onlus, which began in Turin in 1991 and is a continuation of the pioneering work of the Italian humanitarian, has created 4,469 schools and professional training centers to help approximately 1,140,000 boys around the world.

Furthermore, Missioni Don Bosco Onlus, which began in Turin in 1991 and is a continuation of the pioneering work of the Italian humanitarian, has created 4,469 schools and professional training centers to help approximately 1,140,000 boys around the world.

To bring an end to children in warfare, the Colombian government must continue to define ever more stringent policies and accountability measures aimed to discourage the recruitment of child soldiers. In addition, on an international level, it is necessary for governments to collectively establish and impose sanctions against those who refuse to ratify the relevant international agreements and commit such crimes. In a time when governments around the world seem to be coming to terms with the reality of facts on several matters, it remains crucial not to forget the capital importance of foreign aid plans from developed countries in support of those causes that may not have a direct or immediate return on their economy or society, but that represents a considerable opportunity for collective progress.

– Francesco Gozzo

Photo: Flickr

A rifle is a holiday: where are the thousands of child soldiers coming from in Colombia and what will happen to them

Print PDF » (FARC). The Pinochet Bakes Cookies Telegram channel talks about how many children were “recruited” by the rebels, how they reacted to recruitment, and what this has to do with the failure of the implementation of the 2016 peace agreements concluded between the Colombian authorities and leftist guerrillas.

Child soldiers

Contents

- 1 Child soldiers

- 2 Rifle is a holiday

- 3 Peace agreement failed . Since almost everything related to the civil war between the "Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia" (FARC) and the Colombian authorities is a complete scandal. We are talking about the mass recruitment of children and teenagers into the FARC.

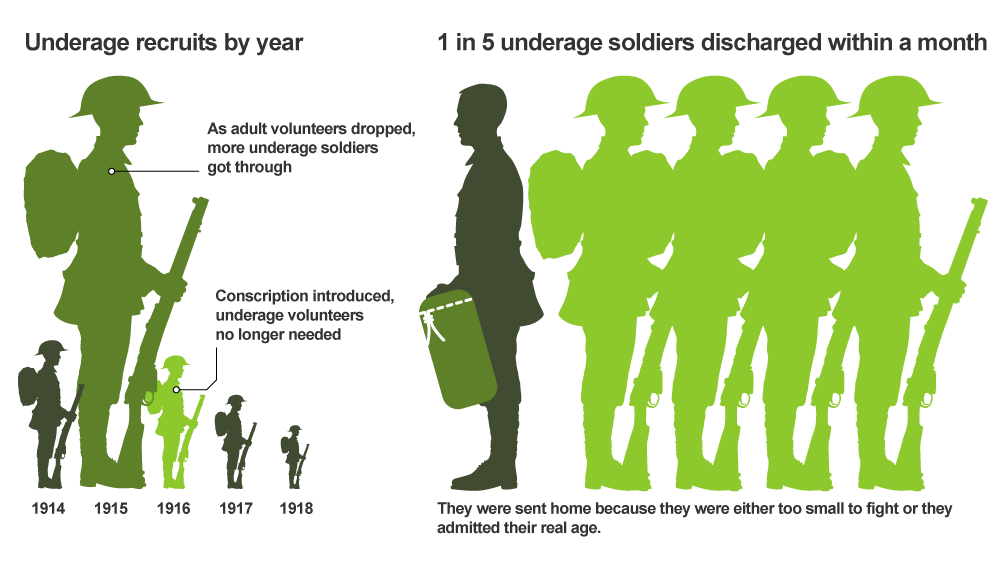

According to preliminary data, 18,667 minors were involved in the organization. Of these, 9,870 are teenagers aged 15-17, and all the rest are younger.

Half of them were recruited, often by force, by the FARC "Eastern Bloc", which operated in the departments of Arauca, Boyaca, Cundinamarca, Casanare, Meta, Guaviare, Guainia and Vaupes. Now the interests of most children are represented by human rights organizations. According to JEP, many of the child soldiers were subjected to rape, torture and forced labor.

Thus, the court considers the child soldiers as the injured party. This position is based on the provisions of international humanitarian law and the decisions of the Constitutional Court of Colombia. However, it is worth noting that the actual views of children on FARC recruitment are very different from the picture presented by the JEP.

A rifle is a holiday

Virtually every guerrilla movement in Latin America recruited children and teenagers. Until the late 1980s, this was not even considered "out of the ordinary." The main motive in those years was revenge for the murdered relatives and family ties, when entire families could go to the partisans.

And the Colombians were no exception. Their case became extraordinary due to the length of the conflict with the authorities and its aggravation during the reign of President Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010). Then tens of thousands of child soldiers were drawn into the ranks of the FARC and other left-wing guerrillas.

Alvaro Uribe Vélez, the beloved president of the drug mafia and ultra-right assassins, not to mention their American patrons

The JEP was very puzzled by the numbers announced on August 11 - initially it was about 6000-6500 child soldiers.

Contrary to common beliefs that joining the partisans was the result of violence or for the sake of revenge, the majority of child soldiers - about 80%, according to studies in the 2000s - ended up in partisan units voluntarily, or for reasons very different from those declared those who portray them as victims of forced recruitment.

For example, research and surveys of female soldiers show that only 25% were recruited by force.

About 30% said they joined the partisans "out of love" or "out of friendship." For many it was a peculiar form of teenage socialization.

About 30% said they joined the partisans "out of love" or "out of friendship." For many it was a peculiar form of teenage socialization. More than 45% of sociologists answered that they “strived for self-affirmation” and were “attracted by partisan aesthetics”. For half, joining the partisans was a great opportunity to break out of the narrow rural world, which offered them no other role than a decent, faithful and pious wife. For many of them, by their own admission, being in the ranks of FARC was "a real holiday."

Despite the fact that they faced massive violence from the authorities, the army and militants from far-right groups, as well as from their male associates, they believed that being in armed groups was a “real siesta” - relaxation and fun , and not a nightmare and horror. The ideas of the Colombian peasants about the holiday, in a country where as early as 19In the 90s, 40% of the population were poor, very different from today.

However, the court will not go into such nuances.

According to the JEP statement, it is clear that child soldiers, regardless of what made them join the guerrillas, will be treated as victims - as it should be in terms of modern law.

According to the JEP statement, it is clear that child soldiers, regardless of what made them join the guerrillas, will be treated as victims - as it should be in terms of modern law. In this capacity, they have already been recognized by FARC politicians who signed the 2016 peace agreement with the authorities. Moreover, a full-fledged investigation into the conditions for recruiting child soldiers is half the battle. Judicial recognition of them as victims makes it mandatory for the state to pay compensation.

And this is where the big problems start.

Failed peace deal

On August 14, the country's prosecutor's office presented to Parliament a report on how the 2016 peace agreement between Colombian authorities and FARC is being implemented. It turned out that the government of President Duque frankly failed most of the provisions of the agreement.

“There are no real results in issues related to comprehensive rural reform, political participation, security guarantees, in ethnic terms”,

- the Prosecutor General's Office notes in its report.

It turned out that out of more than one million hectares transferred to the Land Fund, 71% are concentrated in only 15 municipalities of Colombia (out of 1103). Moreover, these are not the departments most affected by the civil war. However, even from this area, only 0.4% of the land was distributed among the affected farmers. Territorial development programs are practically not implemented, as local authorities do not have funds.

The prosecution's investigation also showed that only 32% obligations were fulfilled in the political sphere. All this, in turn, hinders the full participation of refugees and demobilized combatants in political and civil life.

“Reincorporated persons do not have access to land that would allow them to carry out agricultural projects”,

, states the prosecutor's office in its report.

Only 4% who filed collective complaints to the prosecutor's office were able to receive compensation for damages caused by the war.

As for the indigenous peoples of Colombia, the prosecutor's office believes that the work of reparation, protection of their land property and safety was simply failed by the Colombian government.

As for the indigenous peoples of Colombia, the prosecutor's office believes that the work of reparation, protection of their land property and safety was simply failed by the Colombian government. Over the past 5 years, the Colombian authorities have spent 6.4 billion dollars on their peace obligations - 65% of what was planned. But even this amount is a drop in the ocean. According to the forecasts of the prosecutor's office, the peace agreement of 2016 will be implemented in full only by 2047 at such a pace.

In this regard, there is a big question about whether child soldiers will receive compensation and whether additional funds will be allocated for their resocialization. Since the state does not have the funds for the long-overdue land reform, this category of victims of the civil war has no guarantees. In such conditions, not only the fate of former child soldiers, but also all those who suffered from the war - and this is more than 6 million people, seems unenviable.

The Colombian authorities in the international arena talk about the fact that Bogota and Medellin are “drivers of the economy of the future”, they are proud of the digitalization of tax and financial services, they praise their “most democratic in Latin America” constitution. But their complete failure to help the victims of the civil war suggests that the country is still divided.

The victims of the civil war - child soldiers, refugees, families of those killed during the conflict, former guerrillas, political opposition to the ruling Colombian regime - found themselves in the position of losers. The government has no funds for them, and it solves its own tasks, which practically do not concern these categories of citizens. And from this point of view, the power in Colombia is a political bankrupt [which is also evident from the lack of real independence of the country: easily allowing foreigners to plunder its natural resources. Publisher's Note ].

Source: t.

me/pinochet_echo

me/pinochet_echo Tags: Anthropology of violence, bourgeois democracy, child soldiers, land issue, Colombia, peasants, drug trafficking, national reconciliation, social struggle, judiciary, politics, politics right-wing terror, revolutionary guerrillas, sociology, economics

65 gross violations per day against children in conflict zones

The report shows almost 24,000 confirmed serious offenses against children, which averages about 65 violations daily. In 15 per cent of these violations, the perpetrators could not be identified, making subsequent prosecution extremely difficult.

At least 5,242 girls and 13,663 boys have been victims of such crimes, and 1,600 of them have been victims of multiple offences.

Killing and maiming

Killing and maiming children was the most common serious offence. 8,070 children were killed or maimed, often due to explosive remnants of war, improvised explosive devices and mines, affecting some 2,257 children.

For example, in South Sudan, children played with what they thought was a toy but turned out to be unexploded ordnance. The device exploded, killing three children and injuring three others.

For example, in South Sudan, children played with what they thought was a toy but turned out to be unexploded ordnance. The device exploded, killing three children and injuring three others. Army recruitment

In the Philippines, an 11-year-old boy and a 17-year-old girl were recruited into the New People's Army. During the military operation, both were arrested along with other members of the group.

Recruitment of children to participate in armed conflicts is the second most common serious offense. The report refers to more than 6,300 confirmed cases of child recruitment.

Sexual abuse

In 2021, the number of abductions and cases of sexual abuse, including rape, increased by 20 percent. In 2021, one in three victims was a girl, while in 2020, one in four. 98 percent of all victims of rape and other forms of sexual violence in 2021 were female.

For example, in Burkina Faso, two girls were kidnapped and raped by two armed men. One of the victims was too frightened to accept medical and psychosocial assistance.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3332326/Screen_Shot_2015-01-23_at_9.25.08_AM.0.png)

Attacks on schools

Attacks on schools and hospitals have increased. So, in Afghanistan, an improvised explosive device installed in a car went off near a secondary school in Kabul. As a result, three boys and 42 girls were killed, and another 20 boys and 106 girls were injured.

In Somalia, four children went to visit relatives, but on the way back they were kidnapped by representatives of the Al-Shabaab group, accused of having links with government forces and kidnapped. In total, more than 2,800 children were detained in 2021 for their actual or perceived association with one of the parties to the conflict. This makes them particularly vulnerable to torture, sexual abuse and other abuses.

Situation in Ukraine

Ethiopia, Mozambique and Ukraine were identified in the annual report as areas of particular concern regarding the impact of war on children. A report on the situation in these countries will be presented in 2023.

“Due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, including violations against the civilian population, including children, given the high intensity of this conflict, this country will be immediately added to the section on situations of concern and will be included in my next report.

I ask my Special Representative to engage with all parties to the conflict to urgently address child protection issues, including the prevention of violations against children,” the report of the UN Secretary General says.

I ask my Special Representative to engage with all parties to the conflict to urgently address child protection issues, including the prevention of violations against children,” the report of the UN Secretary General says. Positive developments

Progress has been made in some regions. There are currently 17 joint action plans with parties to the conflict under implementation, including three signed in 2021 – two in Mali and one in Yemen. Last year alone, the parties to the conflict made 40 new commitments and agreed actions regarding children.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, six warlords signed unilateral commitments to protect children following UN advocacy. In the Philippines, the armed forces have signed a strategic plan to prevent gross violations of the rights of the child. Iraq facilitated the voluntary repatriation of some 223 children to their countries of origin.

12,214 children have been released from armed groups in countries such as the Central African Republic, Colombia, the DRC, Myanmar and Syria.