How long does postpartum psychosis last

Postpartum psychosis - NHS

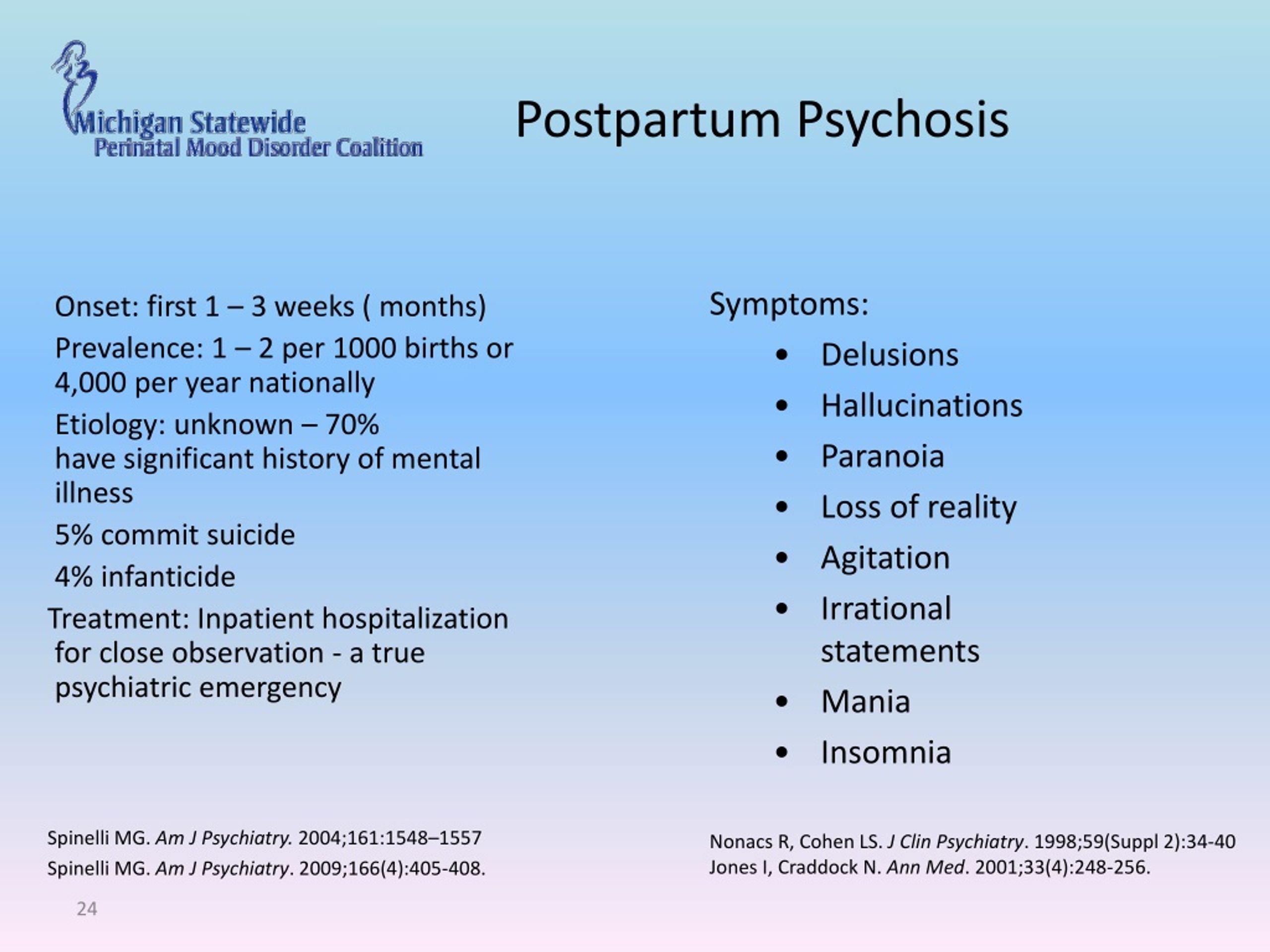

Postpartum psychosis is a serious mental health illness that can affect someone soon after having a baby. It affects around 1 in 500 mothers after giving birth.

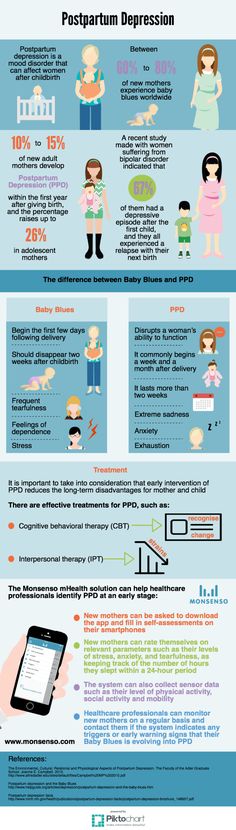

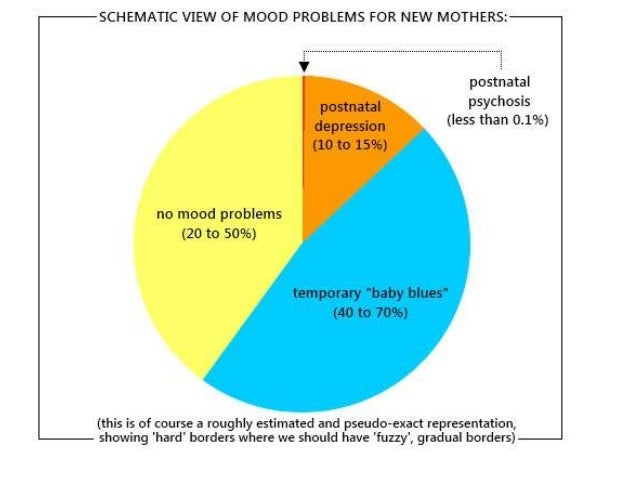

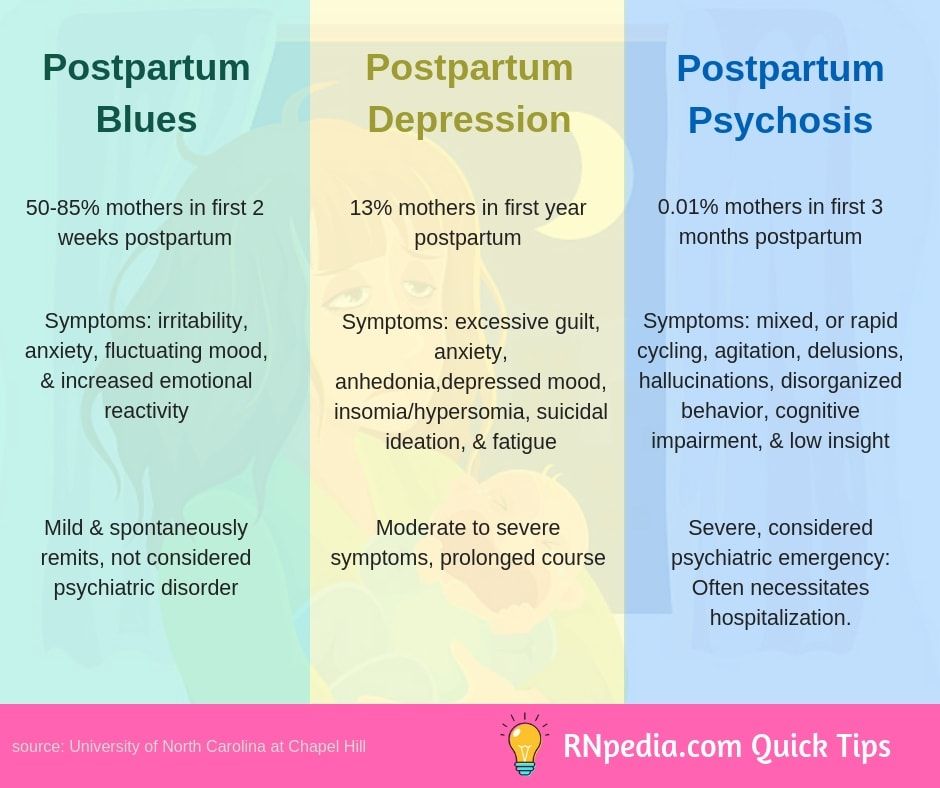

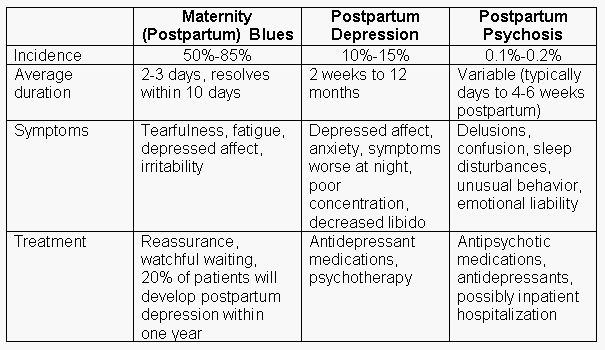

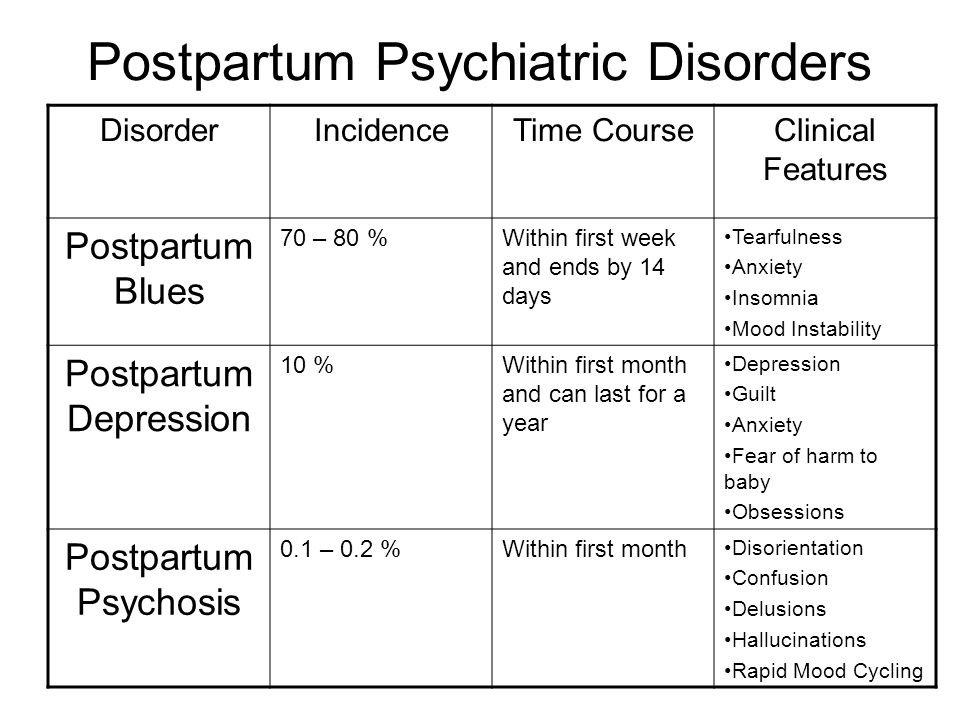

Many people who have given birth will experience mild mood changes after having a baby, known as the "baby blues". This is normal and usually only lasts for a few days.

But postpartum psychosis is very different from the "baby blues". It's a serious mental illness and should be treated as a medical emergency.

It's sometimes called puerperal psychosis or postnatal psychosis.

Symptoms of postpartum psychosis

Symptoms usually start suddenly within the first 2 weeks after giving birth - often within hours or days of giving birth. More rarely, they can develop several weeks after the baby is born.

Symptoms can include:

- hallucinations - hearing, seeing, smelling or feeling things that are not there

- delusions – thoughts or beliefs that are unlikely to be true

- a manic mood – talking and thinking too much or too quickly, feeling "high" or "on top of the world"

- a low mood – showing signs of depression, being withdrawn or tearful, lacking energy, having a loss of appetite, anxiety, agitation or trouble sleeping

- sometimes a mixture of both a manic mood and a low mood - or rapidly changing moods

- loss of inhibitions

- feeling suspicious or fearful

- restlessness

- feeling very confused

- behaving in a way that's out of character

When to get medical help

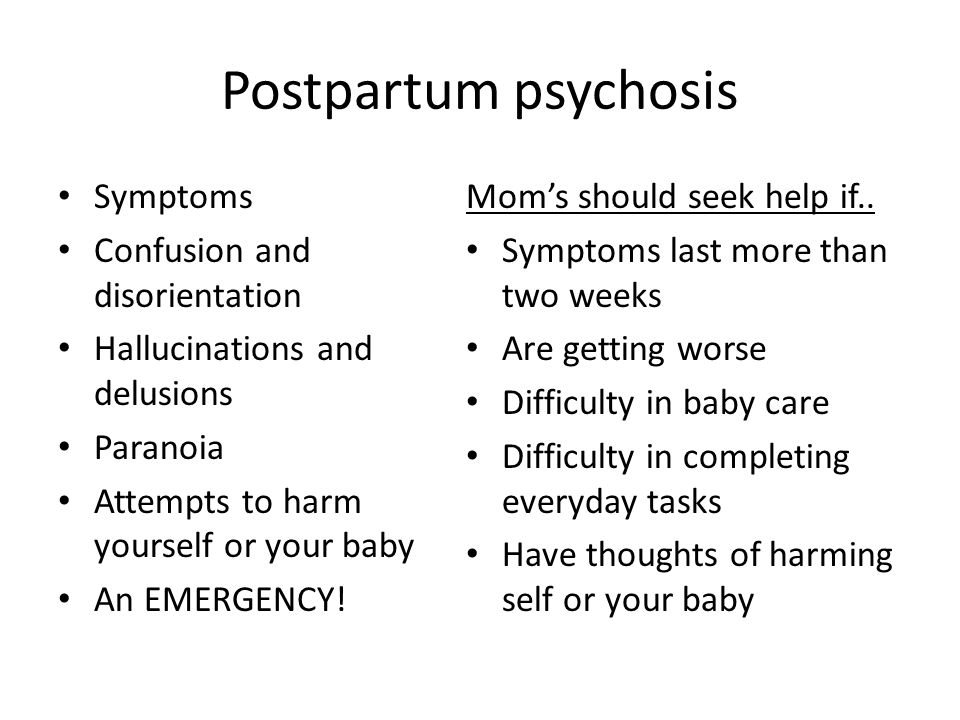

Postpartum psychosis is a serious mental illness that should be treated as a medical emergency. It can get worse rapidly and the illness can risk the safety of the mother and baby.

It can get worse rapidly and the illness can risk the safety of the mother and baby.

See a GP immediately if you think you, or someone you know, may have developed symptoms of postpartum psychosis. You should request an urgent assessment on the same day.

You can call 111 if you cannot speak to a GP or do not know what to do next. Your midwife or health visitor may also be able to help you access care.

Call your crisis team if you already have a care plan because you've been assessed as being at high risk of developing postpartum psychosis.

Go to A&E or call 999 if you think you, or someone you know, may be in danger of imminent harm.

Be aware that if you have postpartum psychosis, you may not realise you're ill. Your partner, family or friends may spot the signs and have to take action.

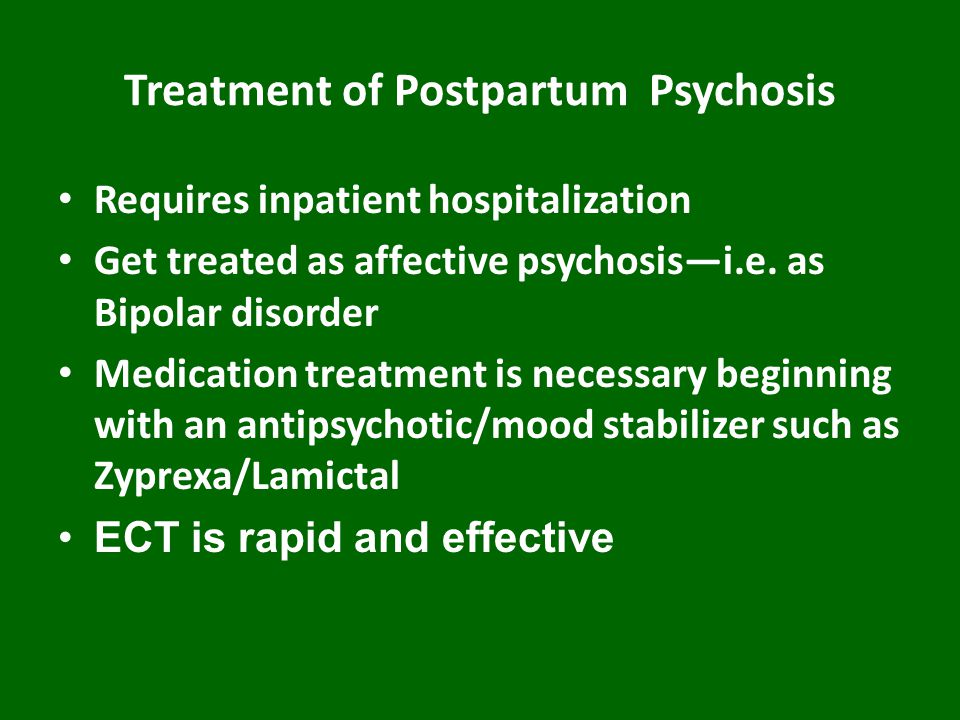

Treating postpartum psychosis

Treatment usually happens in hospital. Ideally, this would be with your baby in a specialist psychiatric unit called a mother and baby unit (MBU). But you may be admitted to a general psychiatric ward until an MBU is available.

Ideally, this would be with your baby in a specialist psychiatric unit called a mother and baby unit (MBU). But you may be admitted to a general psychiatric ward until an MBU is available.

Medicine

You may be prescribed 1 or more of the following:

- antipsychotics – to help with manic and psychotic symptoms, such as delusions or hallucinations

- mood stabilisers (for example, lithium) – to stabilise your mood and prevent symptoms recurring

- antidepressants – to help ease symptoms if you have significant symptoms of depression and may be used alongside a mood stabiliser

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes recommended if all other treatment options have failed, or when the situation is thought to be life threatening.

Most people with postpartum psychosis make a full recovery as long as they receive the right treatment.

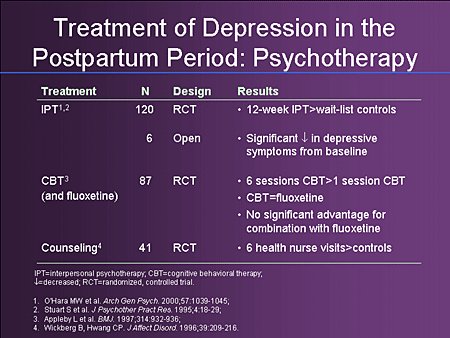

Psychological therapy

As you move forward with your recovery, you may benefit from seeing a therapist for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). CBT is a talking therapy that can help you manage your problems by changing the way you think and behave.

Other forms of support

It can be hard to come to terms with the experience of postpartum psychosis as you recover.

Talking to peers and others with lived experience of the illness may be helpful. Some inpatient units and communities have peer support workers who have experienced the illness, and you can also access support through charities.

Causes

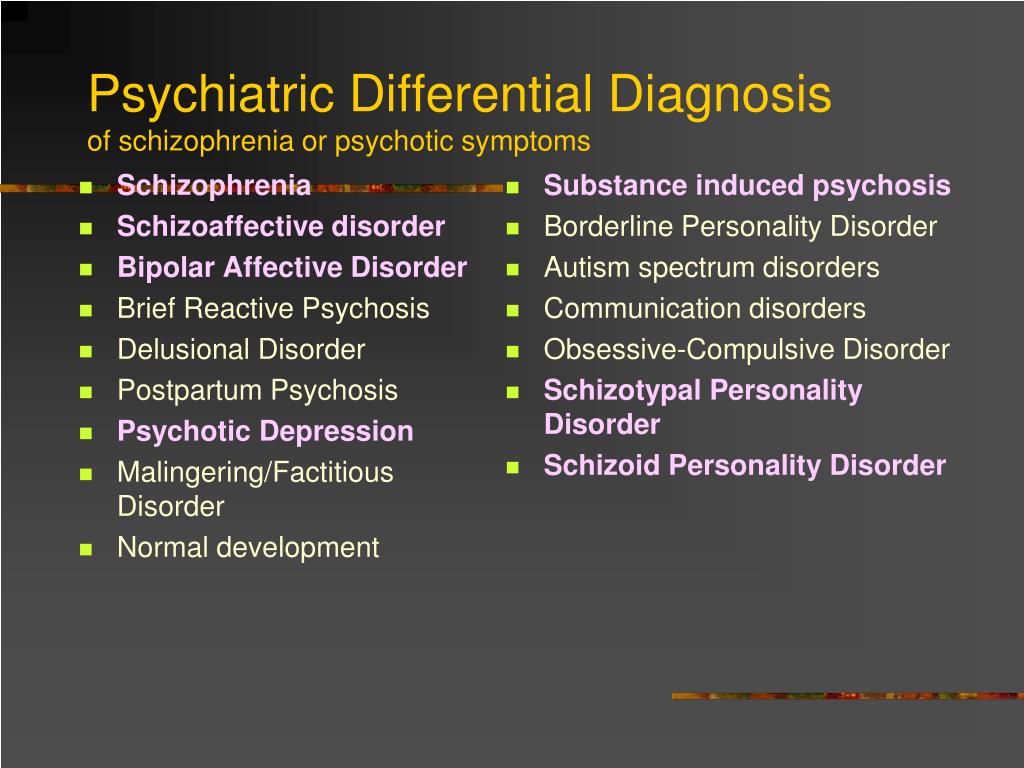

We're not sure what causes postpartum psychosis, but you're more at risk if you:

- already have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia

- have a family history of mental health illness, particularly postpartum psychosis (even if you have no history of mental illness)

- developed postpartum psychosis after a previous pregnancy

Reducing the risk of postpartum psychosis

If you're at high risk of developing postpartum psychosis, you should have specialist care during pregnancy and be seen by a perinatal psychiatrist.

You should have a pre-birth planning meeting at around 32 weeks of pregnancy with everyone involved in your care. This includes your partner, family or friends, mental health professionals, your midwife, obstetrician, health visitor and GP.

This is to make sure that everyone is aware of your risk of postpartum psychosis. You should all agree on a plan for your care during pregnancy and after you've given birth.

You'll get a written copy of your care plan explaining how you and your family can get help quickly if you become ill, as well as strategies you can use to reduce your risk of becoming ill.

In the first few weeks after your baby is born, you should have regular home visits from a midwife, health visitor and mental health nurse.

Recovering from postpartum psychosis

The most severe symptoms tend to last 2 to 12 weeks, and it can take 6 to 12 months or more to recover completely from the condition. But with treatment and the right support, most people with postpartum psychosis do make a full recovery.

But with treatment and the right support, most people with postpartum psychosis do make a full recovery.

An episode of postpartum psychosis is sometimes followed by a period of depression, anxiety and low confidence. It might take a while for you to come to terms with what happened.

Some mothers have difficulty bonding with their baby after an episode of postpartum psychosis, or feel some sadness at missing out on time with their baby. With support from your partner, family, friends and your mental health team, or talking to others with lived experience, you can overcome these feelings.

Many people who've had postpartum psychosis go on to have more children. Although there is about a 1 in 2 chance you will have another episode after a future pregnancy, you should be able to get help quickly with the right care and the risks can be reduced with appropriate interventions.

Support for postpartum psychosis

Postpartum psychosis can have a big impact on your life, but support is available.

It might help to speak to others who've had the same condition, or connect with a charity.

You may find the following links useful:

Action on Postpartum Psychosis (APP)

Action on Postpartum Psychosis (APP) have produced a series of guides with the help of women who have experienced postpartum psychosis.

These guides cover topics such as:

- recovering from postpartum psychosis

- supporting partners

- planning pregnancy

- parenting after postpartum psychosis

- pregnancy for women with bipolar disorder

There is also an APP forum, where you can connect with others affected by postpartum psychosis.

Other useful links

- Mind: what is postpartum psychosis?

- Royal College of Psychiatrists: postpartum psychosis

Supporting people with their recovery

People with postpartum psychosis will need support to help them with their recovery.

You can help your partner, relative or friend by:

- being calm and supportive

- taking time to listen

- helping with housework and cooking

- helping with childcare and night-time feeds

- letting them get as much sleep as possible

- helping with shopping and household chores

- keeping the home as calm and quiet as possible

- not having too many visitors

Support for partners, relatives and friends

Postpartum psychosis can be distressing for partners, relatives and friends, too.

If your partner, relative or friend is going through an episode of postpartum psychosis or recovering, do not be afraid to get help yourself.

Talk to a mental health professional or approach the charities listed.

What It Is, Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

What is postpartum psychosis?

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) is a reversible — but severe — mental health condition that affects people after they give birth. This condition is rare, but it’s also dangerous.

IMPORTANT: People with postpartum psychosis have a much higher risk of harming themselves, dying by suicide or harming their children. Because of this, PPP is a mental health emergency. If you have the symptoms of PPP or are near someone who shows signs of it, it’s important to seek immediate help. If you believe someone is a danger to themselves or others, you should immediately dial 911 (or your local emergency services number).

Who does postpartum psychosis affect?

Postpartum psychosis can affect anyone who recently gave birth. While it usually happens within several days of giving birth, it can happen up to six weeks after.

It can happen to anyone who gives birth, but the odds of having it are higher for people with certain mental health conditions. While experts don’t know if these conditions contribute to or cause PPP, they do know that there’s a link (see below under Causes and Symptoms for more about these conditions).

While experts don’t know if these conditions contribute to or cause PPP, they do know that there’s a link (see below under Causes and Symptoms for more about these conditions).

How common is postpartum psychosis?

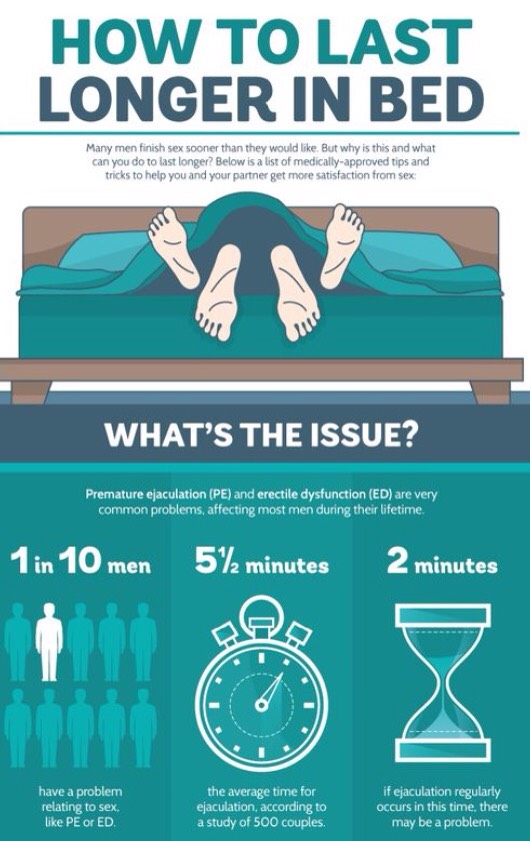

Postpartum psychosis is a rare condition. Experts estimate that it affects between 0.089 and 2.6 out of every 1,000 births. In the United States, that means it happens in between 320 and 9,400 births each year. Globally, that means it happens in between 12 million and 352.3 million births.

Symptoms and Causes

What are the symptoms of postpartum psychosis?

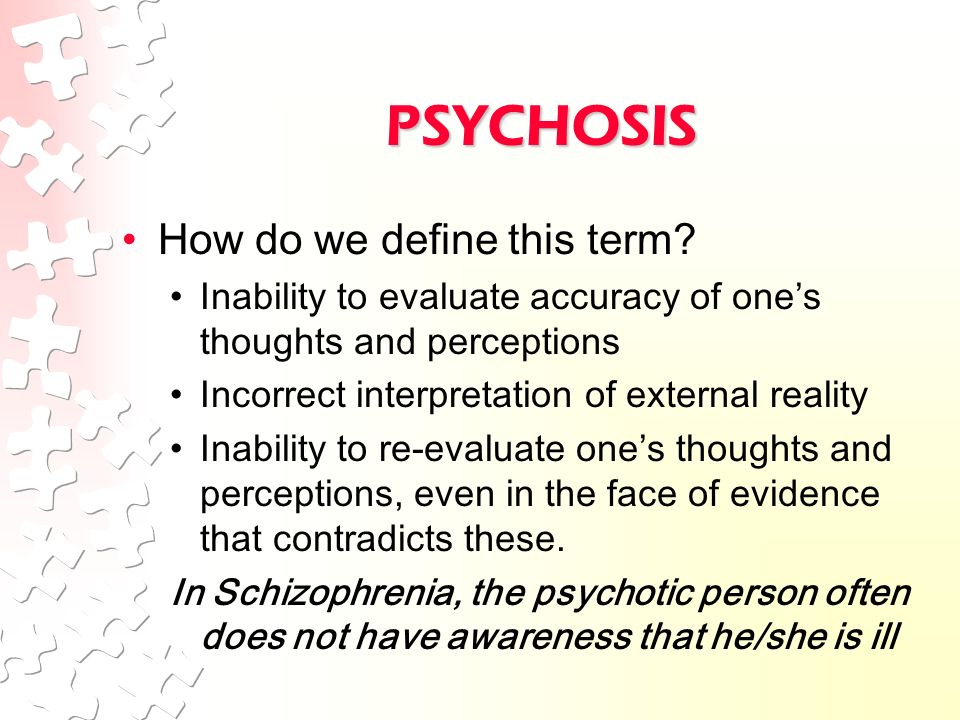

The two main symptoms of psychosis affect a person’s sense of reality and how they understand the world around them. They are:

- Hallucinations. A hallucination is when your brain acts as if it’s getting input from your senses (usually your eyes or ears, but occasionally touch hallucinations can happen, too), but without any actual input. The things you see or hear feel real, and you can’t tell the difference between a hallucination and something that’s truly happening.

- Delusions. Delusions are false beliefs that you hold onto very strongly. If you have a delusion, you hold these beliefs so strongly that you won’t change them even if you have convincing evidence that what you believe isn’t true. Examples include persecutory delusions (believing someone is out to get you), control delusions (feeling that someone else is controlling your body) or somatic delusions (insisting you didn’t have a child or weren’t pregnant).

Other symptoms that are common with postpartum psychosis include:

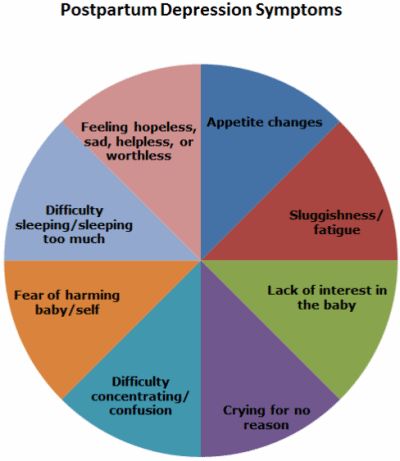

- Mood changes, such as mania (an increase in activity and mood) and hypomania, or depression (a decrease in mood).

- Depersonalization (some people describe this as an out-of-body experience).

- Disorganized thinking or behavior.

- Insomnia.

- Irritability or agitation.

- Thoughts of self-harm or harming others (especially their newborn).

Organizing the symptoms into types

Researchers organize the symptoms of PPP into three types:

- Depressive.

- Manic.

- Atypical/mixed.

Depressive symptoms

The depressive subtype of PPP is the most common, making up about 41% of cases. It’s also the most dangerous. Research shows that depressive symptoms and psychosis are almost always a factor in cases that involve self-harm or harm to a child, especially hallucinations or delusions that command a person to harm their child or themselves. The rate of harm to a child is about 4.5% with this subtype, about four or five times greater than with the other subtypes. The rate of dying by suicide is about 5%.

Symptoms that are most likely with this type include:

- Anxiety or panic.

- Delusions and hallucinations.

- Depression.

- Feelings of guilt.

- Loss of appetite.

- Loss of enjoyment related to things they usually enjoy (anhedonia).

- Thoughts of self-harm, suicide or of harming their child.

Manic symptoms

This is the next most common of the types, affecting about 34% of cases. The risk of self-harm or harm to children is lower but still possible, happening in about 1% of cases.

The risk of self-harm or harm to children is lower but still possible, happening in about 1% of cases.

Symptoms include:

- Agitation or irritability.

- Disruptive or aggressive behavior.

- Talking more or faster than usual (or both).

- Needing less sleep.

- Delusions of greatness or importance (such as believing your child to be a holy or religious figure).

Atypical/mixed symptoms

This subtype makes up about 25% of cases. This can mix the symptoms of manic and depressive subtypes. It can also involve symptoms where a person seems much less aware (or completely unaware) of the world around them.

Symptoms include:

- Disorganized speaking or behavior.

- Disorientation or confusion.

- Disturbance of consciousness (where a person doesn’t appear to be awake or isn’t aware of activities or things taking place nearby).

- Hallucinations or delusions.

- Inappropriate comments, behaviors or emotional displays.

- Catatonia or mutism (being totally silent).

What causes postpartum psychosis?

Experts don’t know why postpartum psychosis happens but suspect it involves a combination of factors, including:

- History of mental health conditions. About one-third of people with PPP have a previously diagnosed mental health condition. The most common include bipolar disorder (especially bipolar I disorder). Other mental health conditions that may increase the risk include major depressive disorder and schizophrenia spectrum conditions.

- Number of pregnancies. PPP is more common in people who just gave birth to their first child. However, for people with a history of PPP, there’s a 30% to 50% chance that it will happen again after future childbirths.

- Family history of mental health conditions, especially PPP. People with PPP often have family members with a history of PPP or related mental health conditions.

Because of that, researchers suspect that this condition may have a genetic link.

Because of that, researchers suspect that this condition may have a genetic link. - Sleep deprivation. Experts know that not getting enough sleep can trigger mania in people with bipolar disorder. They also suspect that not sleeping can be part of why a person develops PPP.

- Hormone changes. Your body’s chemistry during pregnancy undergoes major changes around the time of childbirth. Levels of some hormones spike upward, while others plummet. Experts suspect certain hormones, especially estrogen and prolactin, might play a role. More research is necessary to confirm this, however.

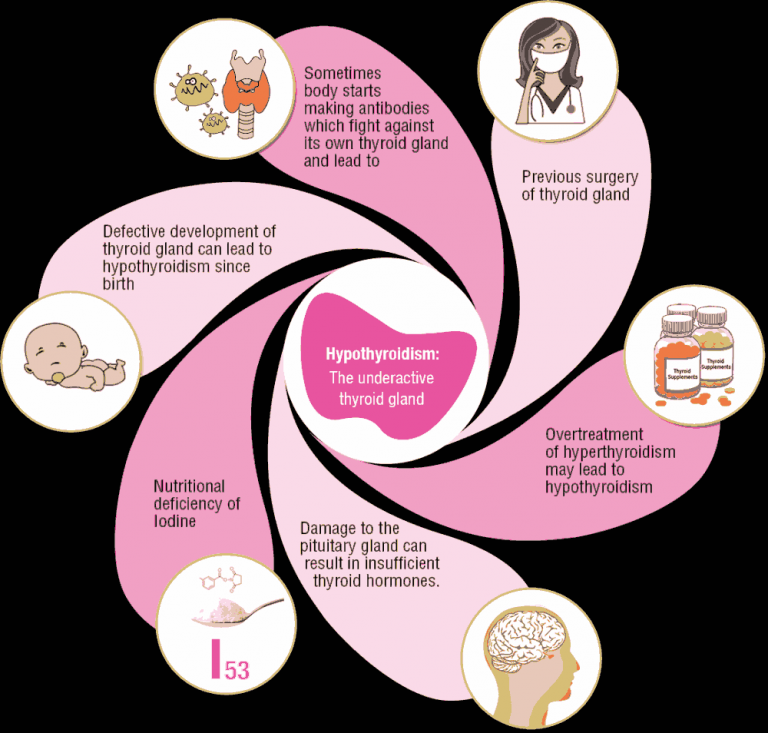

- Other medical conditions. Psychosis can also happen for medical reasons, many of which are possible during or immediately after giving birth. Some examples of medical causes include autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, electrolyte imbalances, vitamin deficiencies (B1 and B12), thyroid disorders, stroke, etc. Eclampsia and preeclampsia also may be contributing conditions.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is postpartum psychosis diagnosed?

A mental health provider can diagnose postpartum psychosis based on your symptoms (either by observation or what you describe) and a physical and neurological exam. Other tests are possible, but these are to rule out other conditions or underlying causes of psychosis. These tests can’t diagnose PPP itself.

Some of the most common tests include:

- Tests on blood, urine or other body fluids. These look for signs of a medical problem, especially with your body’s internal chemistry processes. These can identify infections, electrolyte imbalances, vitamin and mineral deficiencies or excesses, kidney or liver function problems and more.

- Imaging scans. These tests look for changes in your brain structure that might explain your symptoms. The most common imaging scans for this are computerized tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

Your healthcare provider may also use specialized screening tools or questionnaires. These are lists of questions or symptom checklists. Depending on the results of these tools, your provider can determine if you’re likely to have a condition.

Management and Treatment

How is postpartum psychosis treated, and is there a cure?

Postpartum psychosis is treatable, and a few different approaches may work. Unfortunately, the rarity of this condition means there's limited available research on how to treat it. Some methods are in widespread use, but more research is necessary for experts to understand how best to treat this condition.

Because PPP is a mental health emergency, people with this condition need inpatient mental healthcare. This kind of care means trained medical professionals are with them at all times to make sure they’re safe and as comfortable as possible.

Involuntary hospitalization

Because PPP disrupts a person’s sense of reality, many people who have it are completely unaware that they have a mental health or medical issue. Further complicating this is the fact that delusions and hallucinations may actually make them afraid to seek help.

Further complicating this is the fact that delusions and hallucinations may actually make them afraid to seek help.

For those reasons, inpatient mental healthcare for PPP is almost always involuntary. That means the person with PPP is rarely the one who chooses to receive care. Instead, family members, friends or other loved ones must decide to have their loved one hospitalized. This is only an option when there’s reason to believe a person could be a danger to themselves or others.

Treatment methods

The possible treatment methods include:

- Medications.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Medications

Many different medication types can help PPP. The types include:

- Antipsychotic medications.

- Mood stabilizers.

- Antiseizure drugs.

- Lithium.

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a safe and highly effective method for treating conditions that involve psychosis. This treatment uses a mild electrical current, passed through your brain, to induce a mild seizure. The effects of that seizure cause changes in brain activity that reduce or resolve the effects of PPP.

This treatment uses a mild electrical current, passed through your brain, to induce a mild seizure. The effects of that seizure cause changes in brain activity that reduce or resolve the effects of PPP.

ECT often has a negative reputation because of frightening portrayals in books, TV shows and movies. But ECT happens under general anesthesia, so the person receiving it is asleep and won’t feel any pain or discomfort during the procedure.

Once the person is asleep, healthcare providers will place electrodes on the person’s head and pass an electrical current through their scalp and skull and into a specific part of their brain. These seizures usually last less than two minutes, and a provider can use an injectable medication to stop a longer seizure. Most people wake up within 15 minutes after an ECT procedure and can be up and walking around after half an hour.

Complications/side effects of the treatments

The possible complications and side effects depend on many factors, especially the treatments you receive and the symptoms you have. Because of this, your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you the most likely risks, complications or side effects that you can or should expect.

Because of this, your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you the most likely risks, complications or side effects that you can or should expect.

How do I take care of myself or manage symptoms?

Because PPP disrupts your ability to tell what’s real and what isn’t, most people aren’t aware that they have a medical issue. That means this isn’t a condition you can take care of or manage on your own. It’s also very rare for people with PPP to recognize the symptoms, even early on. In almost all cases, others close to the person with PPP will notice the symptoms and act to seek care.

What you can do before becoming pregnant or giving birth

If you have a history of PPP or have conditions like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia (or have a family history of these conditions), it’s important to talk to your healthcare provider about what you can do to plan ahead in case you develop PPP. You also should have a conversation with those closest to you, such as a partner, family member, close friends, etc. These discussions give you a chance to make them aware of your situation and to understand what you want in case you’re unable to make decisions or act for the safety of yourself or your newborn.

These discussions give you a chance to make them aware of your situation and to understand what you want in case you’re unable to make decisions or act for the safety of yourself or your newborn.

How soon after treatment will I feel better, and how long does it take to recover from treatment?

The recovery timeline for PPP depends on many factors, including the specific treatment or medication. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what’s most likely to happen in your case, and can provide information and guidance that’s relevant to you.

Prevention

How can I reduce my risk of developing PPP or prevent it entirely?

PPP happens unpredictably and for reasons that experts don’t fully understand. Because of that, there’s no way to prevent it entirely. But some approaches can reduce the chance of developing it. These are especially important for people who have:

- A previous instance of PPP related to a past childbirth.

- A history of PPP, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or another related condition.

- A family history of any of the conditions mentioned immediately above.

For people who meet any of those criteria, some treatments may reduce the risk of developing it. Lithium, which also treats PPP, is the most common medication used to lower the risk of another occurrence later in life. Other medications may also help reduce the risk of developing it. Your healthcare provider is the best person to explain the options and why they recommend them.

Outlook / Prognosis

What can I expect if I have postpartum psychosis?

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) is a condition that disrupts your sense of reality. The hallucinations and delusions it causes can cause intense fear and anxiety. Unfortunately, the symptoms of this disease mean it’s very rare for you to be aware that you have the symptoms of this mental health condition.

For those around someone with PPP, this condition can also be a source of great anxiety and worry. However, loved ones can also play a very important — if not critical — role in keeping a person with PPP and their children safe (see below to learn more about what you can do to help someone with PPP).

How long does postpartum psychosis last?

PPP is a temporary condition. With treatment, people who have it can recover relatively quickly within a few weeks. Without treatment, PPP can last for weeks or even months. This condition also becomes more severe and more dangerous the longer it goes untreated, so it’s vital that family members or loved ones recognize the symptoms and help get treatment for a person with PPP.

What’s the outlook for this condition?

PPP is a mental health emergency because it affects a person’s sense of reality. The disruptions can be so severe that a person may even attempt suicide or try to harm their child.

With treatment, this condition is reversible and many people who have it go on to have children in the future without a recurrence of PPP. However, most people who have PPP do later develop bipolar disorder. Fortunately, that condition is better understood, and there are multiple methods and approaches for its treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

What can I do if a loved one shows signs of postpartum psychosis?

People with PPP can't recognize their symptoms or understand that they have a mental health condition. That means they don’t believe they need medical care or treatment, and they may misunderstand attempts to help them as a sign that someone is trying to hurt them.

That means they don’t believe they need medical care or treatment, and they may misunderstand attempts to help them as a sign that someone is trying to hurt them.

If you notice a loved one showing signs of PPP, there are things you can do to try to help them.

- Don’t judge or argue. People with PPP have trouble understanding what’s real and what isn’t. Avoid judging them or arguing with them about what’s real and what isn’t, even if you have evidence.

- Stay calm. Paranoia and anxiety are common symptoms of PPP. Staying calm, speaking slowly and keeping your tone lower can help keep a situation from escalating. If someone with PPP is agitated or angry, don’t react in kind. Keep calm and try to make them feel safe and unthreatened. Never make someone with PPP feel as if they’re trapped or in danger.

- Don’t leave them unsupervised either by themselves or with their child. People with PPP have a higher risk of dying by suicide or harming their children.

Because of this, you should never leave someone who might have PPP unsupervised.

Because of this, you should never leave someone who might have PPP unsupervised. - Get emergency help. People with PPP are often a danger to themselves or others. The only way to keep them and their newborn safe is to get them emergency medical care immediately.

- Seek out support. There are numerous groups and agencies — government and private — that offer resources and support for people that PPP affects. Some examples include Postpartum Support International (PSI), the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

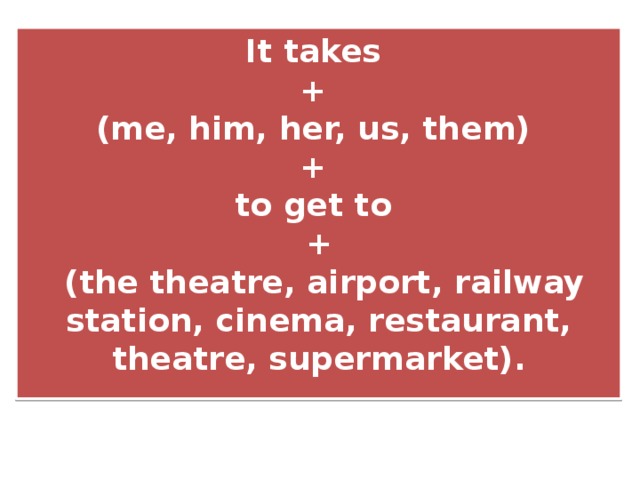

What’s the difference between postpartum psychosis, postpartum blues and postpartum depression?

Postpartum mood changes are very common but can vary from person to person. Some examples in addition to postpartum psychosis include postpartum anxiety, postpartum blues and postpartum depression, including:

- Postpartum anxiety.

Feeling nervous, anxious or worried after giving birth are all very common, normal feelings. Postpartum anxiety is when those feelings become excessive and overwhelming, affecting your ability to function. This can happen with postpartum depression.

Feeling nervous, anxious or worried after giving birth are all very common, normal feelings. Postpartum anxiety is when those feelings become excessive and overwhelming, affecting your ability to function. This can happen with postpartum depression. - Postpartum blues. Also known as “baby blues,” this is very common and happens to about 85% of people who give birth. If you have this, you have trouble controlling strong emotions, especially anxiety, sadness, frustration or anger. You also may struggle with emotion-related behaviors, causing you to cry more than usual or have trouble sleeping. Fortunately, this condition is short-lived and doesn’t need treatment.

- Postpartum depression. This involves similar effects to postpartum blues, but they’re stronger and longer-lasting. The above emotion-related changes also happen with this condition, but they take up much more time in the day or last for days or weeks. That affects how they care for and feel about their child.

It’s also fairly common, affecting about 1 out of every 7 people who give birth.

It’s also fairly common, affecting about 1 out of every 7 people who give birth. - Postpartum psychosis. This is the most severe of these four conditions. This condition also goes beyond mood changes, as its symptoms disrupt your sense of reality.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) is a condition that affects people who just gave birth. This condition is especially severe and dangerous because it disrupts a person’s sense of reality. That puts people with PPP at risk of dying by suicide or harming their children. Fortunately, PPP is a condition that’s treatable and reversible. Many people with this condition ultimately recover, and many have children again in the future without a recurrence of PPP.

Because people with PPP can’t recognize that they have this condition, family and loved ones are the most likely to spot the symptoms of this condition. If you suspect a loved one has PPP, don’t hesitate to get medical help for them by any means necessary. While it may be frightening or worrying to see a loved one experiencing this condition, you can act to keep them and their newborn safe, giving them a chance to recover and return to their life as it was before (with the addition of a new family member, of course).

While it may be frightening or worrying to see a loved one experiencing this condition, you can act to keep them and their newborn safe, giving them a chance to recover and return to their life as it was before (with the addition of a new family member, of course).

Postpartum depression

Page 2 of 7

At least one in 10 mothers suffers from postpartum depression. It is one of the most frequent postpartum complications and occurs in 10-13% of women in labor. As a rule, in such cases it is not always possible to make a correct diagnosis, because mothers are reluctant to seek medical help. Psychotic states in the postpartum period occur in no more than 0.1-0.3% of cases. That is, out of every thousand women who give birth, from 1 to 3 suffer from an even more severe form of depression - postpartum psychosis, in which a woman develops delusions or hallucinations, often accompanied by an obsession with harming herself or the child. The psychotic state significantly impairs the woman's ability to function naturally in family and social life, and also poses a significant risk of committing a suicide attempt. In most cases, the postpartum psychotic state requires urgent hospitalization of the patient. Early postpartum depression develops in the first days or weeks after childbirth, and usually lasts from a week to a month. Late postpartum depression usually develops several months after pregnancy. Its duration can be different, but more often it lasts more than a month.

In most cases, the postpartum psychotic state requires urgent hospitalization of the patient. Early postpartum depression develops in the first days or weeks after childbirth, and usually lasts from a week to a month. Late postpartum depression usually develops several months after pregnancy. Its duration can be different, but more often it lasts more than a month.

Most often, depression appears 30-35 days after birth and in some cases can last up to 1.5-2 years. However, in most cases, a depressive episode ends spontaneously safely 3-6 months after birth. Symptoms of postpartum depression meet the diagnostic criteria for depressive disorder. The patient has a deterioration in mood, a decrease in energy, activity, the ability to rejoice, have fun, a decrease in interests and difficulty in long-term concentration of attention. Severe fatigue is common, even after minimal effort. As a rule, sleep is disturbed and appetite worsens. Self-esteem and self-confidence are almost always reduced, even in mild forms of the disease. Often there are thoughts of one's own guilt and uselessness. Low mood, which varies little from day to day, does not depend on circumstances and may be accompanied by symptoms such as loss of interest in the environment and the loss of sensations that give pleasure. Typical is awakening in the morning several hours earlier than usual, increased depression in the morning, severe psychomotor retardation, anxiety, loss of appetite, weight loss and decreased libido.

Often there are thoughts of one's own guilt and uselessness. Low mood, which varies little from day to day, does not depend on circumstances and may be accompanied by symptoms such as loss of interest in the environment and the loss of sensations that give pleasure. Typical is awakening in the morning several hours earlier than usual, increased depression in the morning, severe psychomotor retardation, anxiety, loss of appetite, weight loss and decreased libido.

In most cases, postpartum depression remains unrecognized in the initial period. The most typical example is the prevailing idea of the "natural whims" or character flaws of a woman in labor who turns to her relatives for help instead of actively caring for the child. Loss of initiative and energy or fear of being judged and discussed by others often prevents a woman from seeking medical help. However, even when contacting a doctor, the disease often remains unrecognized, since some doctors tend to consider this condition as a temporary and natural reaction to the stress that childbirth is, especially for primiparas. At the same time, depression can increase over several months, and the treatment of this condition is delayed until there is an indication for emergency hospitalization.

At the same time, depression can increase over several months, and the treatment of this condition is delayed until there is an indication for emergency hospitalization.

<< First < Previous 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next > Last >>

How long does postpartum depression last?

The article was written by Marina Ilyina , a staff psychologist at the Eleps company, which sells medical equipment (for example, hysteroscopes, EHF devices, endoscopic cameras). One of the most exciting moments in the life of every person is the birth of a child. However, this event is often overshadowed by the onset of postpartum depression in the mother. Unfortunately, in our country the word “depression” is greatly devalued, or ridiculed to such an extent that a person suffering from this disease simply cannot go to the doctor for help. It's the same with postpartum depression. Often, due to different prejudices and mentality, no one notices alarm bells in a patient either during pregnancy or during the formation of depression. Causes

Postpartum depression is a mental disorder that develops in women in labor within 3-6 weeks after the birth of a child. The reasons for the formation of the disorder are very different:

Symptoms

Among the pronounced symptoms in those suffering from depression, depression of mood is manifested, an excessive desire to eat (up to gluttony) or loss of appetite, sleep disturbance (may manifest itself in insomnia, or vice versa in drowsiness), variability of emotions, tearfulness, thoughts about one’s own worthlessness, loss of feeling autonomy and the destruction of one's own opinion. Duration. Postpartum depression is a long illness and it never goes away by itself. On average, postpartum depression can last from 2 to 6 months, and in some cases, it can last up to 2 years. Sometimes the patient's condition improves when the causes of depression begin to be eliminated - the patient is given a rest, some household duties are taken, an idyll begins in married life. Treatment

Postpartum depression can be treated in a variety of ways and with varying degrees of severity. For example, if the patient has a mild form, then it is enough to consult a psychologist, with moderate ones, it is advised to undergo a course of psychotherapy and appropriate medications as prescribed by a doctor, with severe symptoms of depression, hospitalization of the patient is necessary, psychotherapy and drug treatment are mandatory. Among the medical support provided to patients, the following actions can be distinguished:

|

And here is not just the post of CEO of a multi-billion dollar company, but the role of a mother who every second worries about the safety of her child, his health and well-being.

And here is not just the post of CEO of a multi-billion dollar company, but the role of a mother who every second worries about the safety of her child, his health and well-being.  Also, constant anxiety for the well-being of the baby with a neurotic version of postpartum depression. In melancholic depression with a delusional component, there is a sense of guilt and lethargy. With the most common form of depression - prolonged - patients are sure that everything is fine with them. They're just tired and blues. This type of depression develops in a latent form, so a small number of patients turn to specialists. Those who have not done this experience tearfulness, constant fatigue, and it is a burden for them to get up at night for feeding.

Also, constant anxiety for the well-being of the baby with a neurotic version of postpartum depression. In melancholic depression with a delusional component, there is a sense of guilt and lethargy. With the most common form of depression - prolonged - patients are sure that everything is fine with them. They're just tired and blues. This type of depression develops in a latent form, so a small number of patients turn to specialists. Those who have not done this experience tearfulness, constant fatigue, and it is a burden for them to get up at night for feeding.  Yes, when the cause is eliminated, the condition can even out, but if the patient abruptly returns to the previous rhythm of life after a while, then the condition can become much worse than before.

Yes, when the cause is eliminated, the condition can even out, but if the patient abruptly returns to the previous rhythm of life after a while, then the condition can become much worse than before.