How does an autistic child communicate

Autism Spectrum Disorder: Communication Problems in Children

What is autism spectrum disorder?

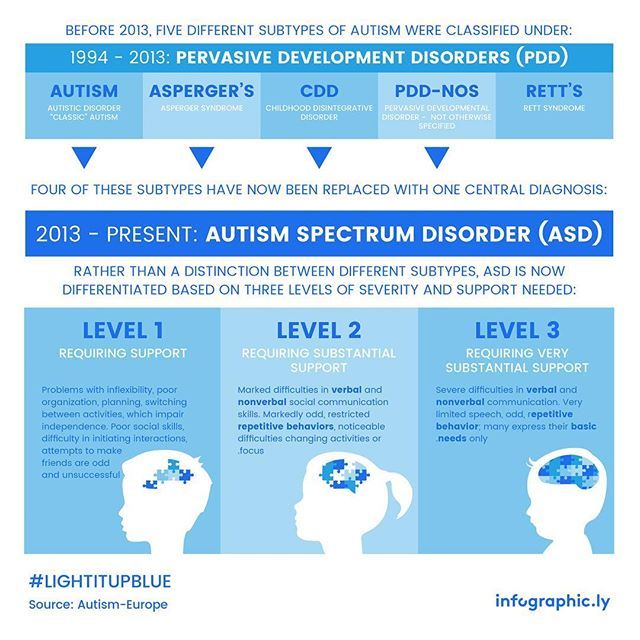

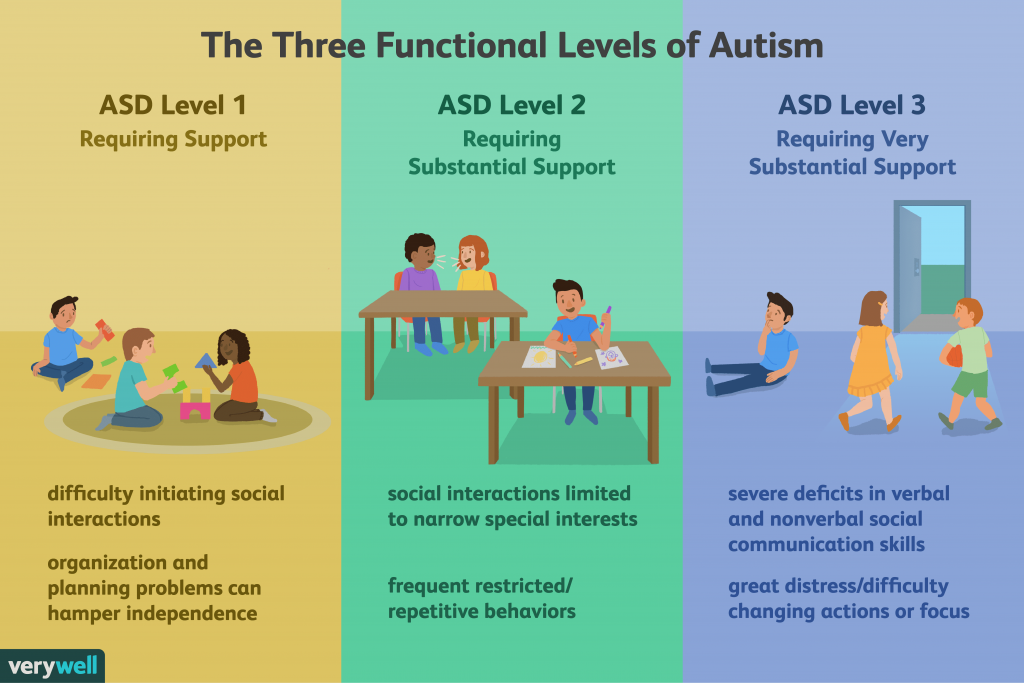

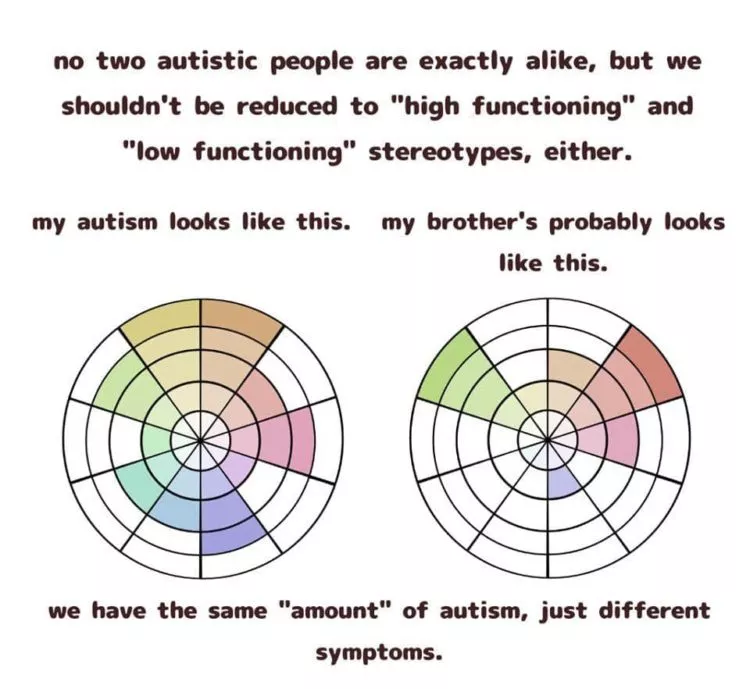

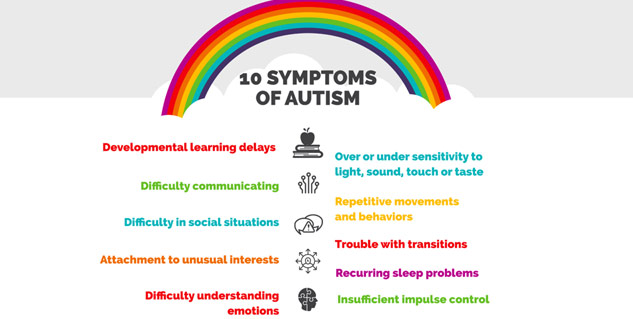

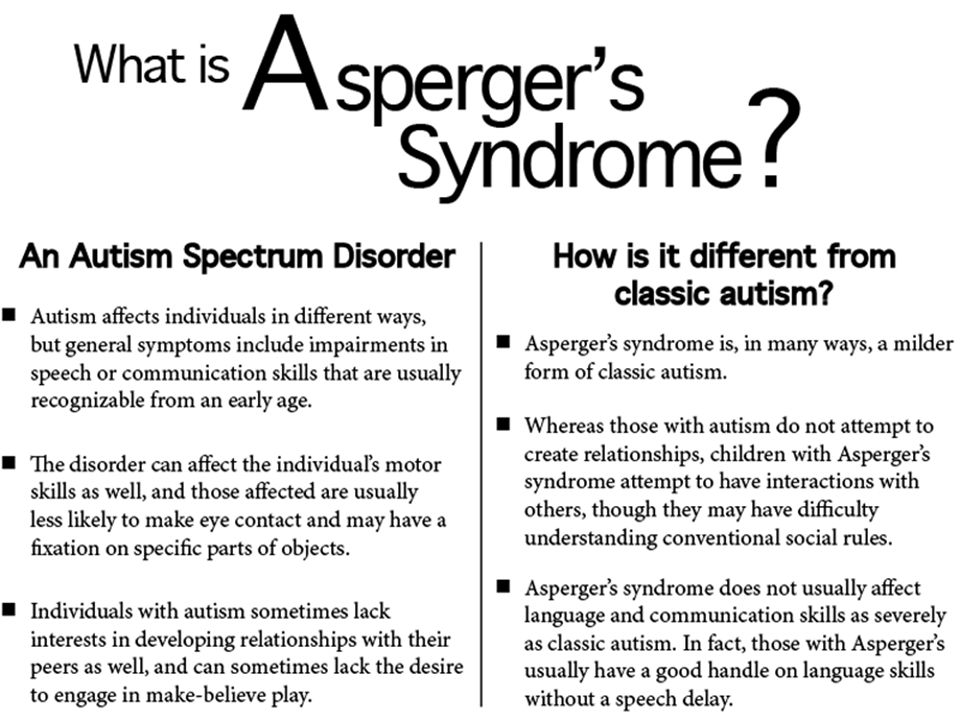

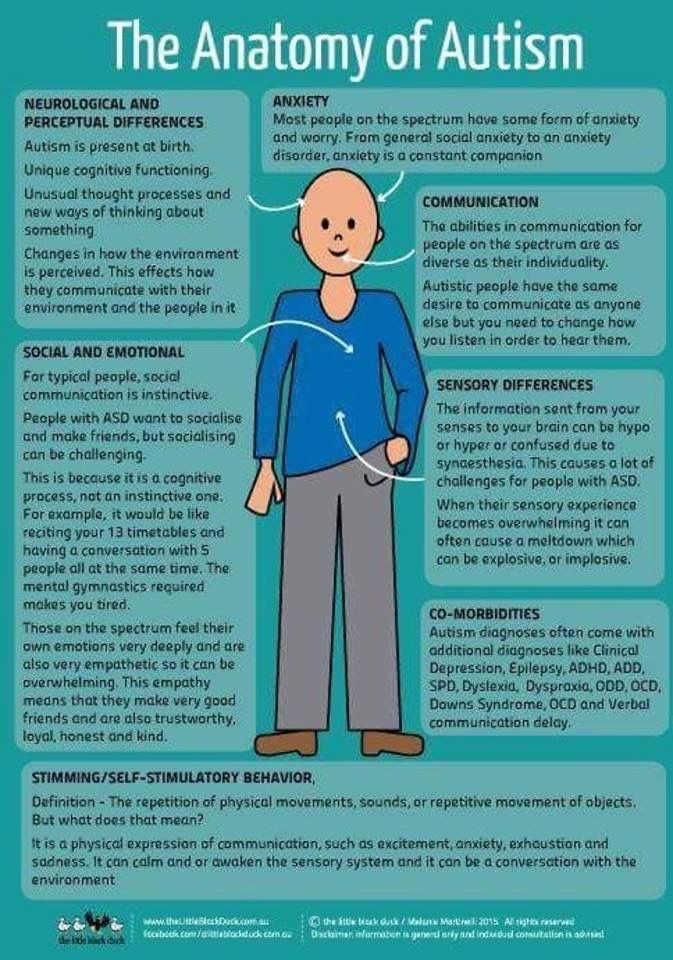

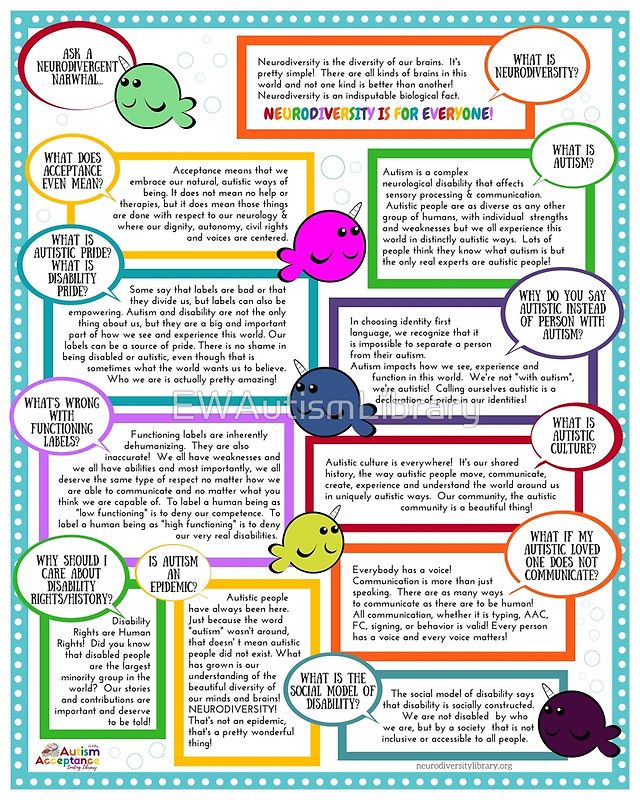

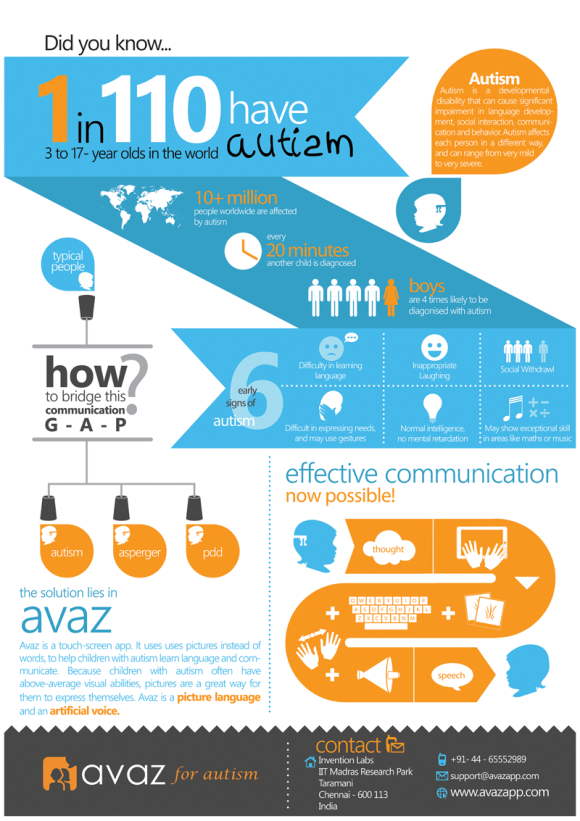

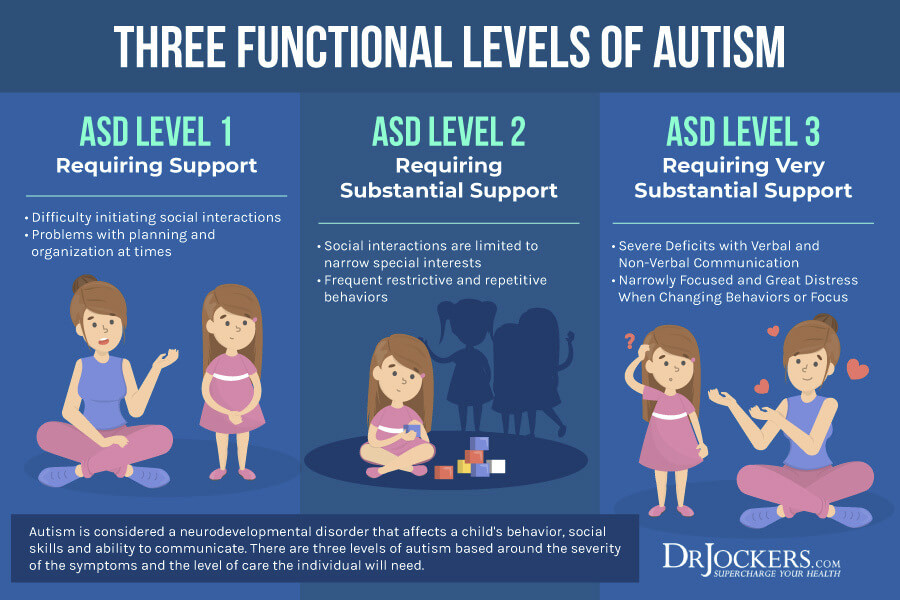

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability that can cause significant social, communication, and behavioral challenges. The term “spectrum” refers to the wide range of symptoms, skills, and levels of impairment that people with ASD can have.

ASD affects people in different ways and can range from mild to severe. People with ASD share some symptoms, such as difficulties with social interaction, but there are differences in when the symptoms start, how severe they are, the number of symptoms, and whether other problems are present. The symptoms and their severity can change over time.

The behavioral signs of ASD often appear early in development. Many children show symptoms by 12 months to 18 months of age or earlier.

Who is affected by ASD?

ASD affects people of every race, ethnic group, and socioeconomic background. It is four times more common among boys than among girls. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 1 in every 54 children in the U.S. has been identified as having ASD.

How does ASD affect communication?

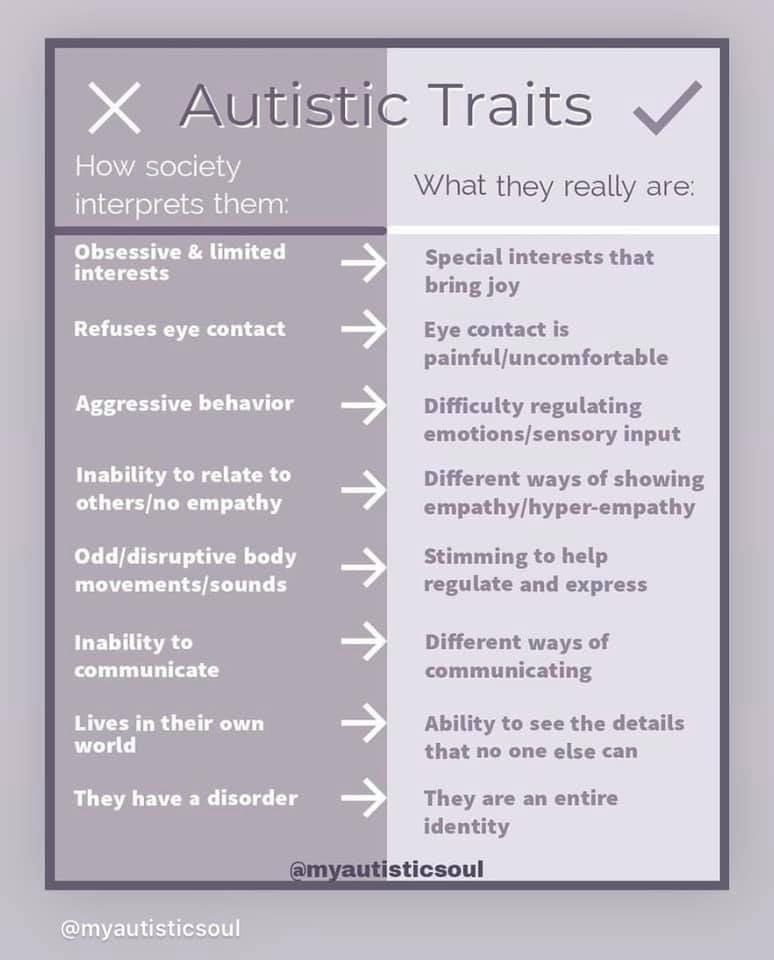

The word “autism” has its origin in the Greek word “autos,” which means “self.” Children with ASD are often self-absorbed and seem to exist in a private world in which they have limited ability to successfully communicate and interact with others. Children with ASD may have difficulty developing language skills and understanding what others say to them. They also often have difficulty communicating nonverbally, such as through hand gestures, eye contact, and facial expressions.

The ability of children with ASD to communicate and use language depends on their intellectual and social development. Some children with ASD may not be able to communicate using speech or language, and some may have very limited speaking skills. Others may have rich vocabularies and be able to talk about specific subjects in great detail. Many have problems with the meaning and rhythm of words and sentences. They also may be unable to understand body language and the meanings of different vocal tones. Taken together, these difficulties affect the ability of children with ASD to interact with others, especially people their own age.

Many have problems with the meaning and rhythm of words and sentences. They also may be unable to understand body language and the meanings of different vocal tones. Taken together, these difficulties affect the ability of children with ASD to interact with others, especially people their own age.

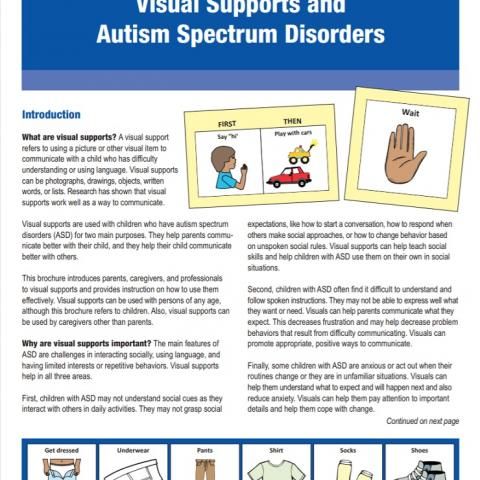

Below are some patterns of language use and behaviors that are often found in children with ASD.

- Repetitive or rigid language. Often, children with ASD who can speak will say things that have no meaning or that do not relate to the conversations they are having with others. For example, a child may count from one to five repeatedly amid a conversation that is not related to numbers. Or a child may continuously repeat words he or she has heard—a condition called echolalia. Immediate echolalia occurs when the child repeats words someone has just said. For example, the child may respond to a question by asking the same question. In delayed echolalia, the child repeats words heard at an earlier time.

The child may say “Do you want something to drink?” whenever he or she asks for a drink. Some children with ASD speak in a high-pitched or sing-song voice or use robot-like speech. Other children may use stock phrases to start a conversation. For example, a child may say, “My name is Tom,” even when he talks with friends or family. Still others may repeat what they hear on television programs or commercials.

The child may say “Do you want something to drink?” whenever he or she asks for a drink. Some children with ASD speak in a high-pitched or sing-song voice or use robot-like speech. Other children may use stock phrases to start a conversation. For example, a child may say, “My name is Tom,” even when he talks with friends or family. Still others may repeat what they hear on television programs or commercials. - Narrow interests and exceptional abilities. Some children may be able to deliver an in-depth monologue about a topic that holds their interest, even though they may not be able to carry on a two-way conversation about the same topic. Others may have musical talents or an advanced ability to count and do math calculations. Approximately 10 percent of children with ASD show “savant” skills, or extremely high abilities in specific areas, such as memorization, calendar calculation, music, or math.

- Uneven language development. Many children with ASD develop some speech and language skills, but not to a normal level of ability, and their progress is usually uneven.

For example, they may develop a strong vocabulary in a particular area of interest very quickly. Many children have good memories for information just heard or seen. Some may be able to read words before age five, but may not comprehend what they have read. They often do not respond to the speech of others and may not respond to their own names. As a result, these children are sometimes mistakenly thought to have a hearing problem.

For example, they may develop a strong vocabulary in a particular area of interest very quickly. Many children have good memories for information just heard or seen. Some may be able to read words before age five, but may not comprehend what they have read. They often do not respond to the speech of others and may not respond to their own names. As a result, these children are sometimes mistakenly thought to have a hearing problem. - Poor nonverbal conversation skills. Children with ASD are often unable to use gestures—such as pointing to an object—to give meaning to their speech. They often avoid eye contact, which can make them seem rude, uninterested, or inattentive. Without meaningful gestures or other nonverbal skills to enhance their oral language skills, many children with ASD become frustrated in their attempts to make their feelings, thoughts, and needs known. They may act out their frustrations through vocal outbursts or other inappropriate behaviors.

How are the speech and language problems of ASD treated?

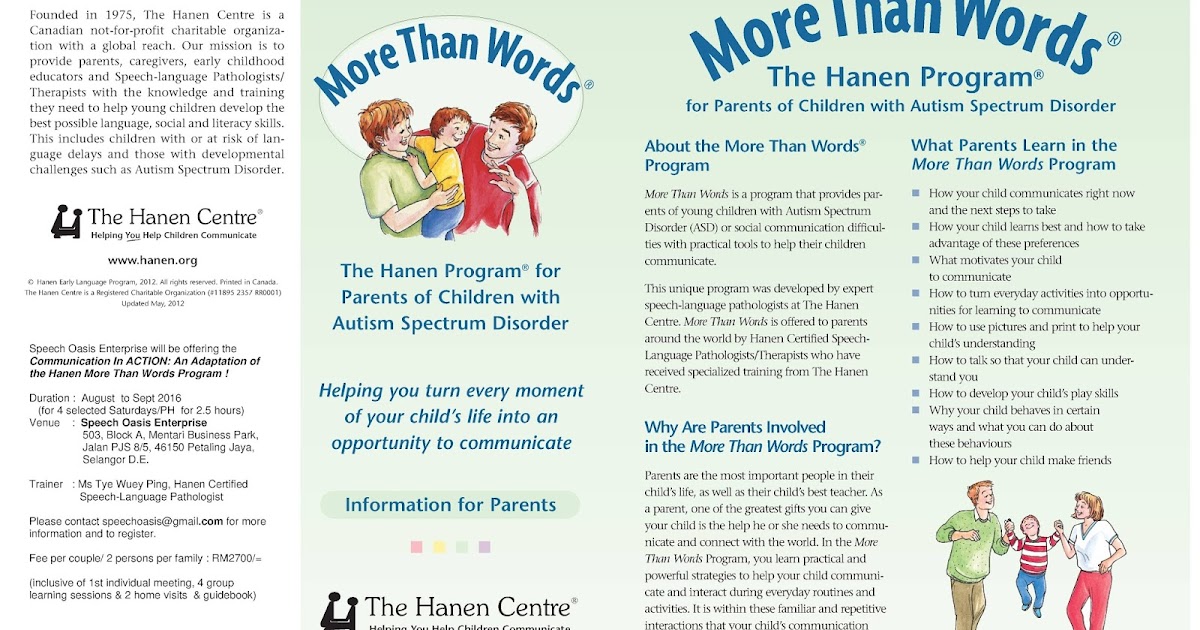

If a doctor suspects a child has ASD or another developmental disability, he or she usually will refer the child to a variety of specialists, including a speech-language pathologist. This is a health professional trained to treat individuals with voice, speech, and language disorders. The speech-language pathologist will perform a comprehensive evaluation of the child’s ability to communicate, and will design an appropriate treatment program. In addition, the speech-language pathologist might make a referral for a hearing test to make sure the child’s hearing is normal.

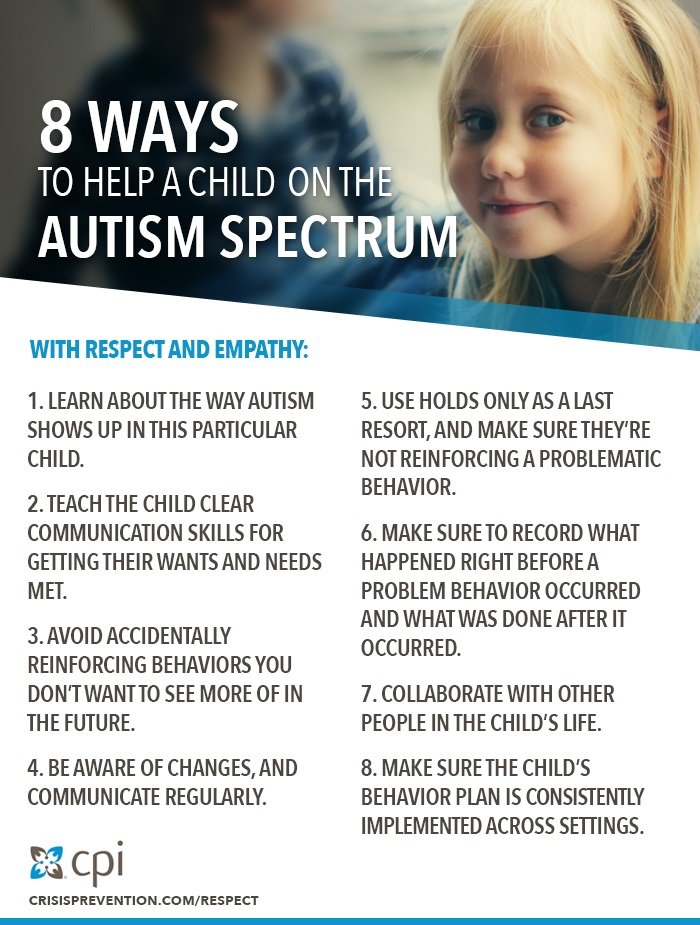

Teaching children with ASD to improve their communication skills is essential for helping them reach their full potential. There are many different approaches, but the best treatment program begins early, during the preschool years, and is tailored to the child’s age and interests. It should address both the child’s behavior and communication skills and offer regular reinforcement of positive actions. Most children with ASD respond well to highly structured, specialized programs. Parents or primary caregivers, as well as other family members, should be involved in the treatment program so that it becomes part of the child’s daily life.

Most children with ASD respond well to highly structured, specialized programs. Parents or primary caregivers, as well as other family members, should be involved in the treatment program so that it becomes part of the child’s daily life.

For some younger children with ASD, improving speech and language skills is a realistic goal of treatment. Parents and caregivers can increase a child’s chance of reaching this goal by paying attention to his or her language development early on. Just as toddlers learn to crawl before they walk, children first develop pre-language skills before they begin to use words. These skills include using eye contact, gestures, body movements, imitation, and babbling and other vocalizations to help them communicate. Children who lack these skills may be evaluated and treated by a speech-language pathologist to prevent further developmental delays.

For slightly older children with ASD, communication training teaches basic speech and language skills, such as single words and phrases. Advanced training emphasizes the way language can serve a purpose, such as learning to hold a conversation with another person, which includes staying on topic and taking turns speaking.

Advanced training emphasizes the way language can serve a purpose, such as learning to hold a conversation with another person, which includes staying on topic and taking turns speaking.

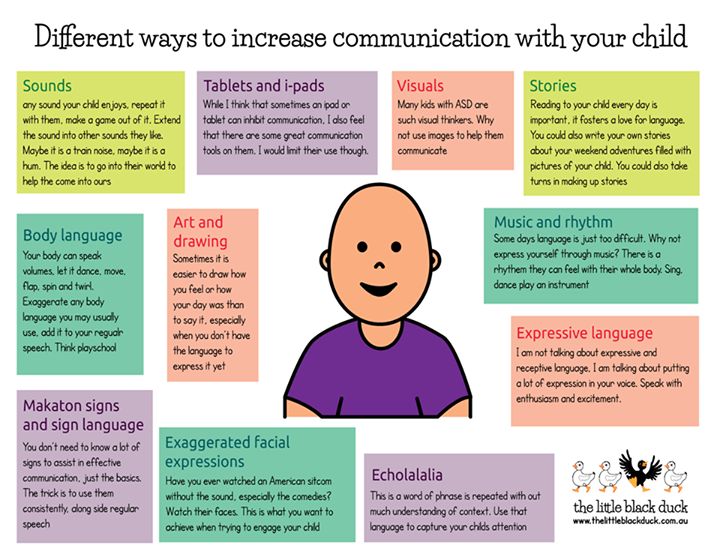

Some children with ASD may never develop oral speech and language skills. For these children, the goal may be learning to communicate using gestures, such as sign language. For others, the goal may be to communicate by means of a symbol system in which pictures are used to convey thoughts. Symbol systems can range from picture boards or cards to sophisticated electronic devices that generate speech through the use of buttons to represent common items or actions.

What research is being conducted to improve communication in children with ASD?

The federal government’s Autism CARES Act of 2014 brought attention to the need to expand research and improve coordination among all of the components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that fund ASD research. These include the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), along with the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH).

Together, five institutes within the NIH (NIMH, NIDCD, NICHD, NIEHS, and NINDS) support the Autism Centers of Excellence (ACE), a program of research centers and networks at universities across the country. Here, scientists study a broad range of topics, from basic science investigations that explore the molecular and genetic components of ASD to translational research studies that test new types of behavioral therapies. Some of these studies involve children with ASD who have limited speech and language skills, and could lead to testing new treatments or therapies. You can visit the NIH Clinical Trials website and enter the search term “autism” for information about current trials, their locations, and who may participate.

The NIDCD supports additional research to improve the lives of people with ASD and their families. An NIDCD-led workshop focused on children with ASD who have limited speech and language skills, resulting in two groundbreaking articles.1 Another NIDCD workshop on measuring language in children with ASD resulted in recommendations calling for a standardized approach for evaluating language skills. The benchmarks will make it easier, and more accurate, to compare the effectiveness of different therapies and treatments.

The benchmarks will make it easier, and more accurate, to compare the effectiveness of different therapies and treatments.

NIDCD-funded researchers in universities and organizations across the country are also studying:

- Ways to reliably test for developmental delays in speech and language in the first year of life, with the ultimate goal of developing effective treatments to address the communication challenges faced by many with ASD.

- How parents can affect the results of different types of language therapies for children with ASD.

- Enhanced ways to improve communication between children with and without ASD. This could involve a communication board with symbols and pictures, or even a smartphone app.

- Techniques to help researchers better understand how toddlers with ASD perceive words, and the problems they experience with words.

- Cost-effective ways to prevent or reduce the impact of conditions affecting speech, language, and social skills in high-risk children (for example, younger siblings of children with ASD).

- The development of software to help people with ASD who struggle with speech to communicate complex thoughts and interact more effectively in society.

Where can I find additional information about ASD?

Information from other NIH Institutes and Centers that participate in ASD research is available on the NIH Health Information page by searching on the term “autism.”

In addition, the NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free Voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

Email: [email protected]

5 Ways Individuals with Autism Communicate

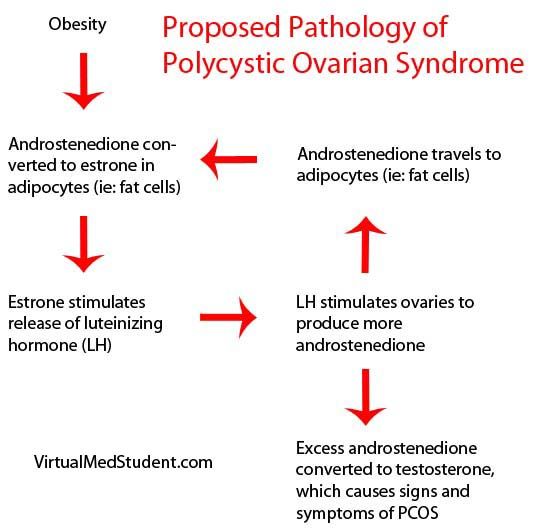

Even verbally fluent individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have unique methods of communication; below, we’ve compiled five of the most common ways individuals with autism communicate. We tend to think of communication as a language-based tool, however, a large portion of communication is non-linguistic, relying on body-language, gestures, and tone of voice. Let’s take a look at these communication methods–bearing in mind that we’ll primarily be discussing the social communication skills present in high-functioning individuals with ASD.

We tend to think of communication as a language-based tool, however, a large portion of communication is non-linguistic, relying on body-language, gestures, and tone of voice. Let’s take a look at these communication methods–bearing in mind that we’ll primarily be discussing the social communication skills present in high-functioning individuals with ASD.

1. Non-Verbal Communication

Many people affected by ASD develop little in the way of language skills, relying instead on non-verbal communication techniques. These include a wide range of behaviors, such as using:

- Gestures

- Pictures or drawings

- Crying and other emotive sounds

- Physically directing someone’s hand to an object they want

While this can cause communication difficulties, parents and caregivers often become quite adept at reading these non-linguistic communications through context clues and repetition. For more information on non-verbal communication, the U.K.-based National Autistic Society has a wealth of information.

2. Echolalia

Echolalia refers to the repetition of phrases that people have heard, perhaps in a favorite movie or television program. These phrases may or may not “fit” the context in which they are spoken, however, they typically do point to something concrete. Parents of autistic children are encouraged to watch the programs in which these phrases are spoken to attempt to figure out what their child might be trying to communicate when they use particular phrases.

3. Focusing on the Literal Meanings of Words

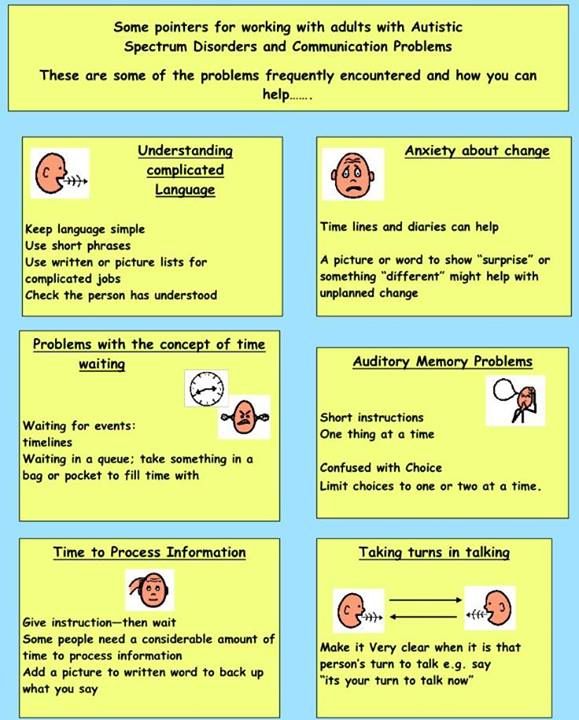

Individuals with some form of ASD typically have trouble understanding idiomatic language and metaphors. Another implication of this trait is a difficulty understanding jokes and humor, which often rely on a sarcastic tone to convey the speaker’s true meaning. A hallmark of the ways individuals with autism communicate is focusing on the “key words” of a sentence. One of the best ways to accommodate this communication style is to speak in simple, plain sentences without idioms or figures of speech that hide the “true message” you’re trying to convey.

4. Moving from Topic to Topic

One difficulty individuals with autism find with communication is the ability to “stay on topic.” Because their minds are moving very quickly and processing many stimuli, their thoughts may seem disorganized or unfocused. However, this usually isn’t the case–unless an ASD individual has expressed the desire to stop talking about a given topic (in which case, you should definitely move on), they’re usually open to revisiting previous conversation topics.

5. Speaking with no Eye Contact

The last tool we’ll look at in the 5 ways individuals with autism communicate is the fact that often they will speak with you, but will not make eye contact. People affected by this condition are highly attuned to sensory details, and looking into someone’s eyes can cause an overload of information. Some may prefer to speak with their eyes shut entirely, so as to focus only on the stimuli provided by the conversation. Understanding and accommodating this variety of communication is key to building better communication with ASD individuals.

Related Resource: Top 20 Best Applied Behavior Analysis Programs

We’ve aimed to highlight some of the most common communication traits of individuals with autism. For a more extensive list and other information about ASD, the Indiana Resource Center for Autism’s website is a fantastic resource. We hope our list of the ways individuals with autism communicate has expanded your understanding of these unique communication methods.

How to communicate with a child with autism?

21.12.13

Recommendations to parents on the development of positive relations with a child

Source: Living well with autism

Use the declarative language

,9000 declarative statements allow you to share or divide the topics want, but do not require a verbal response from your child. This approach models for the child the natural language spoken by other children, which can increase the child's desire to communicate with you. Use declarative language to compliment, secret, surprise, comment, and share your emotions.

Use declarative language to compliment, secret, surprise, comment, and share your emotions. - Share experiences and emotions: "I'm so hungry", "I'm not having fun at all", "Wow, look at this!", "I wonder if it will snow today?"

- Invite the child to do something with you: "Let's go to the playground", "Here come the soap bubbles!"

- Celebrate the child's victories: "Excellent!", "High five!", "We did it!"

- Encourage or offer solutions: "Can you do it!", "Let's take a break?"

- Reminisce about past experiences (use a photo album with photos of specific situations for this): "We had so much fun", "This trip is my favorite."

- Describe actions (instead of instructions): "We'll put on our boots", "Run together, run so fast!".

The child does not have to respond to declarative statements in any way, but he may do so verbally or non-verbally. In my experience, declarative statements expand my child's social language skills, increase their willingness to cooperate and desire to communicate.

On the other hand, imperative statements and questions put pressure on the child - they require response communication from him, they tell him what to do, they force him to make a choice, they demand the right answer.

Examples of imperative phrases: How old are you? What is color? Say thank you". What do you want to play? Put on your boots.

Teachers almost always speak to students in imperative phrases. Such phrases are simple and allow you to achieve quick results. But unlike a declarative language, they do not model natural communication. Almost any imperative statement can be formulated as declarative if you get creative.

In some situations, imperative phrases are necessary, but it is necessary to reduce the proportion of imperative language in your speech. Imperative phrases should make up no more than 20% of your entire communication.

Model social communication

Use the forms of communication with your child that you would like to hear from him. If you want to hear "please", "thank you" and "sorry", then do not forget to say these words yourself in relation to your child.

If you want to hear "please", "thank you" and "sorry", then do not forget to say these words yourself in relation to your child.

Communication zone

Stand in close proximity to the child before speaking. Be at eye level (bend over, sit down, lift the child higher), no further than at arm's length, with the maximum level of contact. Do not try to get the child's attention from across the room!

Don't go beyond your child's abilities

Children with autism may be good in one area but delayed in other areas. For example, your child may find it very difficult to throw or even roll a ball, but they may enjoy jumping on an exercise ball.

A common mistake is overestimating the child's ability to complete simple tasks or take part in a game. Look for ways to make the task easier. When communicating with a child, rely on what he definitely knows how to do.

Do simple, short, everyday activities together, such as brushing your teeth together at the same time, or sealing and mailing letters. Modeling such actions by adults helps the child learn.

Modeling such actions by adults helps the child learn.

Then you will understand that it is time to move on to the next level. Make it fun.

Respect eye contact features

Do not insist on eye contact with commands such as "Look at me" and do not praise for "Good look". Research shows that direct eye contact can be uncomfortable for some people with autism, and that it can cause anxiety. In my experience, natural, social eye contact develops over time as a child learns to pay attention to other people's faces while interacting.

Accompany your speech with non-verbal and alternative communication

Many children with autism find it difficult to process other people's spoken language and may be constantly distracted by other stimuli from the outside world. When communicating with a child, do not just talk - use your whole body, including facial expressions, movements of your arms and legs.

Accompany your speech with photographs and drawings that reflect what you are talking about. Learn a few signs from sign language and accompany them with the appropriate words (this can be very helpful).

Learn a few signs from sign language and accompany them with the appropriate words (this can be very helpful).

Try to be "numb" for a while and, as a game, communicate with your child exclusively non-verbally and through alternative means. Your child's reaction may surprise you!

Visual attention, pointing, and the theory of the mind

One of the classic symptoms of autism is that children do not point to objects to draw attention to them. It is believed that children with autism have problems with the theory of mind - it can be difficult for them to understand that you think differently than they do.

However, you can encourage the development of this skill. For example, if your face will show the information that the child needs, then you will teach the child to visually pay attention to other people's faces. To do this, make your face more cheerful and interesting for attention. Increase your facial expressions and gestures. Use makeup, a hat, or glasses to make your face an interesting subject for a child.

It is hardly useful to constantly tell a child with autism that your experience and thoughts are desperate when the child does not have the skills to understand it. I saw my son begin to tell the teachers about his birthday party: “Do you remember…” To which the teachers replied: “No, I don’t remember, because I wasn’t there.” This only caused confusion in the son, and he stopped talking. Before the development of the theory of the mind, one could answer: “It must have been a lot of fun! I love birthday cake." Or: “Are you talking about your birthday? It must have been a lot of fun." And then wait for the child to continue sharing the experience.

Make your speech important

If you want to get a child's attention, you don't have to repeat his name all the time. Try to get attention with a gesture or a cough. Say his name once and then pat him on the shoulder. No need to repeat the name several times in a row, the child will simply learn to ignore it, including in situations where you need him to respond to the name.

Do not overload the child with too long phrases, let the length of the sentences in your speech correspond to the capabilities of your child. Perhaps a child can only take in a few words at a time! Do not "lisp", do not talk to the child like a baby, just simplify your speech.

Make your speech important by emphasizing key words in sentences with volume, pauses, intonation, emphasis, and more. The following rules are recommended when talking to a child with autism: speak less, emphasize key words, speak slowly and show what you mean with gestures or visual materials.

Parenting, Communication and Speech

How to communicate with an autistic person? 15 tips for every day

Five ways to show acceptance towards autistic children

1. Be patient. In fact, this applies to any children without exception. Children have the right to be with you in this world, they have the right to fully participate in this world, which will soon be theirs. Children in general, but especially children with special needs, can only learn proper social behavior, they can make noise in the library (but if they love books loudly, how can you be mad at them?), they can constantly fidget around you in airplane, they might burst into tears in line at the supermarket checkout because they saw that chocolate bar (maybe you need it too, you just learned how to express your desires in a socially acceptable way). Without a doubt, we all misbehaved at least occasionally (or often), and if we were lucky, then there were patient and understanding adults next to us, even if we ourselves lacked patience.

Children in general, but especially children with special needs, can only learn proper social behavior, they can make noise in the library (but if they love books loudly, how can you be mad at them?), they can constantly fidget around you in airplane, they might burst into tears in line at the supermarket checkout because they saw that chocolate bar (maybe you need it too, you just learned how to express your desires in a socially acceptable way). Without a doubt, we all misbehaved at least occasionally (or often), and if we were lucky, then there were patient and understanding adults next to us, even if we ourselves lacked patience.

2. Ask and listen. My son is speaking. This is our blessing, and this is what we have worked long and hard for. What he says is usually full of meaning (although sometimes this meaning is known only to himself) and an unusual way of looking at things. My son speaks slowly, extremely slowly, he often repeats parts of a sentence several times, he speaks in a quiet monotonous voice, practically without facial expressions, without gestures, without looking into his eyes. Stop, sit down to be at his level, listen to him, give him time to find his words, give him the opportunity to speak - he really has something to say. He taught me a lot, and I learned to trust him, even when I think he's making things up, like that pink concrete mixer, but he actually saw it at the construction site down the street.

Stop, sit down to be at his level, listen to him, give him time to find his words, give him the opportunity to speak - he really has something to say. He taught me a lot, and I learned to trust him, even when I think he's making things up, like that pink concrete mixer, but he actually saw it at the construction site down the street.

3. Discuss their interests with them. A quote from Temple Grandin recently made me think about children and their personal understanding of their autism: are we encouraging them to think too much about their differences from other people? While it seems to me important that we as adults show understanding for these children, they are not limited to their diagnoses, impairments, and neurological differences. It seems to me that this is the moment when "acceptance" becomes more important than "informing about the problem." True acceptance means that you accept that something is part of your world and your life, but you don't have to think about it all the time. Many children on the autism spectrum have very surprising interests, or interests that only they can see something amazing in, these interests allow them to maintain peace of mind and peace of mind, and sometimes, with the right support and encouragement, they can become experts in the field. your interest and make it your career. Ask my daughter anything about condors and you'll have a very long (and very informative) conversation that I'm sure you'll enjoy just as much as she did. Join my son as he collects little pebbles in the park. This is soothing, and you will immediately establish a relationship with him that cannot be achieved with words alone.

Many children on the autism spectrum have very surprising interests, or interests that only they can see something amazing in, these interests allow them to maintain peace of mind and peace of mind, and sometimes, with the right support and encouragement, they can become experts in the field. your interest and make it your career. Ask my daughter anything about condors and you'll have a very long (and very informative) conversation that I'm sure you'll enjoy just as much as she did. Join my son as he collects little pebbles in the park. This is soothing, and you will immediately establish a relationship with him that cannot be achieved with words alone.

4. Communicate with them and accept their communication with you. Most children on the autism spectrum have some form of communication problem, ranging from severe to subtle. If the child does not speak and does not have other means of communication, then you can observe his behavior, what he does, what gives him pleasure - communicate at this level or just be around without the usual communication, for many this is already a very big step . I don't have much experience with non-speaking children, but I know that behavior is communication, and if you are accepting of a child and comfortable in their presence, then this is also a form of communication that can be very useful for you. both. Children who can speak also have differences in communication, so we must be aware that when communicating with them, some stereotypical aspects of communication may be missing (for example, very often it is eye contact), in addition, they may interpret language differently ( see point 2).

I don't have much experience with non-speaking children, but I know that behavior is communication, and if you are accepting of a child and comfortable in their presence, then this is also a form of communication that can be very useful for you. both. Children who can speak also have differences in communication, so we must be aware that when communicating with them, some stereotypical aspects of communication may be missing (for example, very often it is eye contact), in addition, they may interpret language differently ( see point 2).

5. Love them. Because what else do all children need if not love and acceptance? (Besides oxygen, food, water and a roof over your head, but you get my point).

Five ways to show acceptance towards autistic adults

1. Show respect. Whether a person has a visible disability or not, whether communication is difficult or not, everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. It seems to me that there is no point in explaining this point, but it does not prevent us all from thinking it over.

2. Communicate with them. No matter how the person communicates with you, including if they use an iPad, computer, SMS, typing, or spoken language to communicate, listen to them, ask questions, and listen for answers. Autistic people are the ultimate experts on their experiences, and there is something for everyone to learn from them. Many adults on the autism spectrum work very hard to share their ideas and important experiences with others about autism as part of our world. There are plenty of examples of this: this is the new book by Carly Fleischman, and the biography of Temple Grandin and the funny comics “Dude, I’m an Aspie!”

3. Analyze your own behavior. Do you do anything strange when you are alone? Does it happen that you interrupt other people? Don't you have a habit of tapping your foot on the floor or your fingers on the table when you're nervous or bored? Each of us has self-stimulating or self-regulating behaviors. The repetitive behavior in autism may get more attention, it may be much more intense or stereotyped, but the essence is the same. And we all make social mistakes from time to time and are unwittingly rude or annoying. Everyone breaks the unwritten social rules from time to time.

And we all make social mistakes from time to time and are unwittingly rude or annoying. Everyone breaks the unwritten social rules from time to time.

4. Think of an apology. As Muslims, our family follows the "make up an apology" rule (or at least they should). Some people complain that autistic people are rude or annoying, but if we know that the person is autistic (and even if we don't), we should "think of excuses" for their actions before getting offended and ignoring the other person. Someone may seem impolite, for example, as John Elder Robinson describes in his book Be Different, a person can change the TV channel even though there are other people in the room watching it. But is there malicious intent in such behavior? Or has the person really not noticed that other people are watching TV, or that they are even present in the room?

5. Give up pity. Pity involves speculation about other people's failures and feeling superior due to one's own good fortune. One can feel sorry for someone who has suffered a sudden misfortune - the loss of a family member, cancer, the destruction of a house during a natural disaster. These are sudden events that we have no control over. Pitying a person just because their mind or body has evolved differently than yours means that you consider that person helpless and that you ignore their attempts to use their existing abilities and strengths to control their life as much as possible. Pity is the exact opposite of acceptance, give it up.

One can feel sorry for someone who has suffered a sudden misfortune - the loss of a family member, cancer, the destruction of a house during a natural disaster. These are sudden events that we have no control over. Pitying a person just because their mind or body has evolved differently than yours means that you consider that person helpless and that you ignore their attempts to use their existing abilities and strengths to control their life as much as possible. Pity is the exact opposite of acceptance, give it up.

Five ways to show acceptance towards parents of autistic children

1. Stop using catastrophic language. This is dangerous. We can control how we react and how we communicate with parents, and the media bears the lion's share of the responsibility for this. Do not escalate the situation, do not say that you are sorry, because despair has a dangerous effect on parents, because of such views, children were killed!

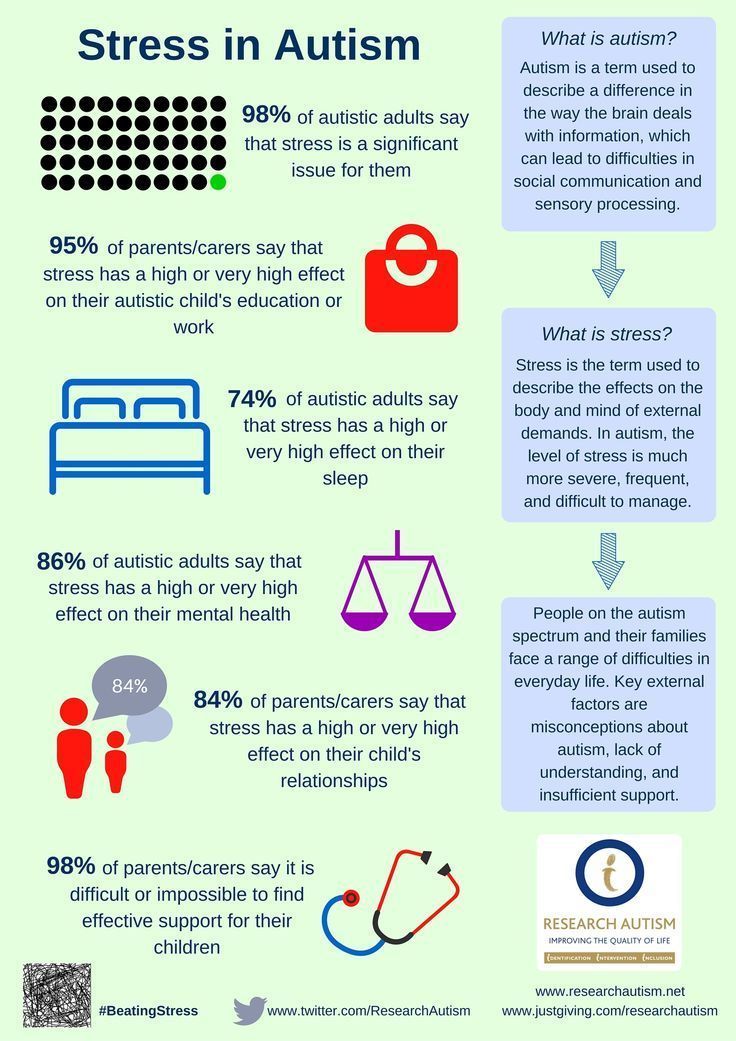

2. Stay close. This is the most reliable way to help. If parents suffer from stress or chronic fatigue, listen to them. Offer them ready meals, washing dishes, babysitting. And at the same time, do not forget about point 1.

If parents suffer from stress or chronic fatigue, listen to them. Offer them ready meals, washing dishes, babysitting. And at the same time, do not forget about point 1.

3. Do not judge or give "good advice". "I've been reading about diet/theory/research/treatment", "Have you heard that Jenny McCarthy...", "I'm sure he'll outgrow it", "You need to be more consistent." You want the best, we understand that, but we've heard it all before, it's just another media hysteria, just another legacy of accusations against parents. I have learned to ask questions rather than offer advice or opinions about things I don't know: "What therapies are you planning to try?" Tell me what will happen! or simply “I would like to offer you some solution. If you want to talk, then let me know, at least I will always listen.

4. Invite them. That party that is sure to be too intense for their special child? Invite them anyway. Make it clear you're really looking forward to them, ask early in the planning stage, and work with parents (and your child, if possible) to make your party more accessible, sensory-friendly, safe, relaxed, and welcoming.