How do you get strep b pregnancy

Group B Strep and pregnancy

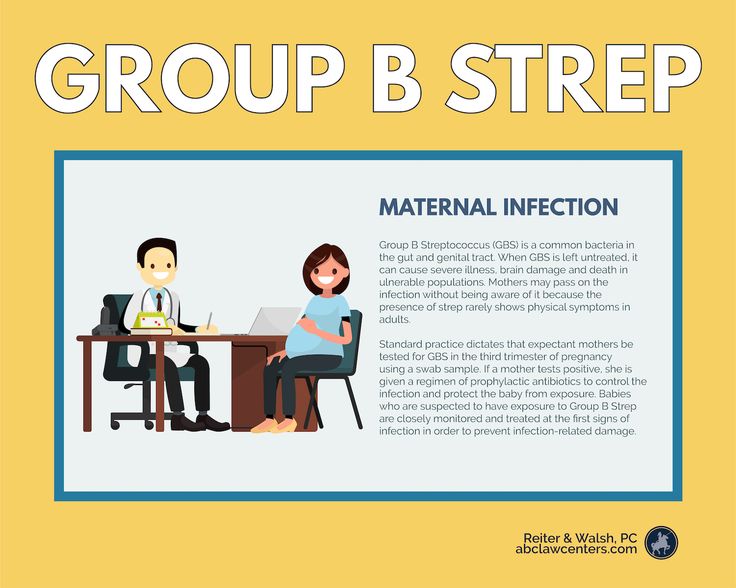

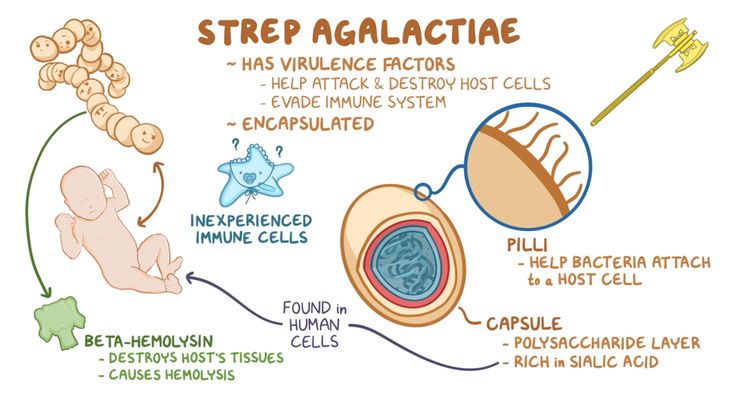

Group B Streptococcus (Group B Strep, Strep B, Beta Strep, or GBS) is a type of bacteria which lives in the intestines, rectum and vagina of around 2-4 in every 10 women in the UK (20-40%). This is often referred to as ‘carrying’ or being ‘colonised with’ GBS.

Group B Strep is not a sexually transmitted disease. Most women carrying GBS will have no symptoms. Carrying GBS is not harmful to you, but it can affect your baby around the time of birth.

GBS can occasionally cause serious infection in young babies and, very rarely, during pregnancy before labour.

Key points

- Group B Strep is one of the many bacteria that normally live in our bodies and which usually cause no harm

- Testing for GBS is not routinely offered to all pregnant women in the UK

- If you carry GBS, most of the time your baby will be born safely and will not develop an infection. However, it can rarely cause serious infection such as sepsis, pneumonia or meningitis

- Most early-onset GBS infections (those developing in the first week of life) are preventable

- If GBS is found in your urine, vagina or rectum (bowel) during your current pregnancy, or if you have previously had a baby affected by GBS infection, you should be offered antibiotics in labour to reduce the small risk of this infection to your baby.

- If GBS was found in a previous pregnancy and your baby was unaffected, you can have a specific swab test (known as the ECM test) to see whether you are carrying GBS when you are 35-37 weeks pregnant. If the test result is positive, you will be offered antibiotics in labour. If the ECM test result is negative at this point, then the risk of your baby developing early-onset GBS infection is low and you may choose not to have antibiotics.

- The risk of your baby becoming unwell with GBS infection is increased if your baby is born preterm, if you have a temperature while you are in labour, or if your waters break before you go into labour

- If your newborn baby develops signs of GBS infection, they should be treated with antibiotics straight away

The information below is for you, a friend or a relative who is expecting a baby, planning to become pregnant or has recently had a baby.

FIND OUT HOW TO ORDER AN ECM TEST FOR GBS

WHERE TO Order your GBS test

How do people become carriers of group B Strep?

Like many bacteria, GBS may be passed from one person to another through skin-to-skin contact, for example, hand contact, kissing, close physical contact, etc. As GBS is often found in the vagina and rectum of colonised women, it can be passed through sexual contact.

As GBS is often found in the vagina and rectum of colonised women, it can be passed through sexual contact.

There are no known harmful effects of carriage itself and the GBS bacteria do not cause genital symptoms or discomfort. GBS carriage is not a sexually transmitted disease, nor is GBS carriage a sign of ill health or poor hygiene.

No-one should ever feel guilty or dirty for carrying GBS – it’s normal. Around 20-40% of women carry GBS.

GBS may be passed from one person to another by skin-to-skin contact. Everyone (regardless of whether they know they carry GBS) should wash their hands properly and dry them properly before handling a newborn baby.

How is group B Strep found?Most women carrying GBS have no symptoms, so GBS is often found by chance through a vaginal or rectal swab test or a urine test.

The NHS does not routinely test all pregnant women for group B Strep.

Tests designed specifically to find GBS carriage, known as the Enriched Culture Medium (ECM) test, are increasingly becoming available within the NHS and are widely available privately.

Since September 2017, the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RCOG) has recommended in their guideline on group B Strep that selected pregnant women should be offered the ECM test. Many maternity units still use a standard test that misses up to half of the women carrying group B Strep, so ask your health professionals what is available locally.

There are private home ECM testing kits for GBS carriage you can order.

What could group B Strep mean for my baby?Many babies come into contact with group B Strep during labour, or around or after birth and the vast majority will not become ill.

However, there is a small chance that your newborn baby will develop group B Strep infection and become seriously ill, or even die, and this chance is increased if you are carrying GBS.

The infections that group B Strep most commonly causes in newborn babies are sepsis (infection of the blood), pneumonia (infection in the lungs), and meningitis (infection of the fluid and lining around the brain).

Around 1 in every 1750 babies in the UK and Ireland is diagnosed with early-onset group B Strep infection (developing in babies aged 0-6 days).

Around 1 in every 2700 babies in the UK and Ireland is diagnosed with late-onset group B Strep infection (developing in babies aged 7-90 days).

Although group B Strep infection can make your baby very unwell, with prompt treatment most babies will recover fully.

Of the babies who develop GBS infection, 1 in 19 (5.2%) will die from early-onset GBS infection and 1 in 13 (7.7%) from late-onset GBS infection. Of those who survive their GBS infection, 1 in 14 (7.4%) will have a long-term disability following early-onset GBS infection and 1 in 8 (12.4%) following late-onset GBS infection.

On average in the UK and Republic of Ireland, every month

- 66 babies are diagnosed with group B Strep infection

- 40 early-onset + 26 late-onset GBS infection

- 56 babies make a full recovery

- 35 early-onset + 21 late-onset GBS infection

- 6 babies survive with long-term physical or mental disabilities

- 3 early-onset + 3 late-onset GBS infection

- 4 babies die from their group B Strep infection

- 2 early-onset + 2 late-onset GBS infection

Any baby can develop a group B Strep infection, but early-onset group B Strep infection (developing in the first 6 days of life, and usually on the first day of life) is more likely if:

- your baby is born preterm (before 37 weeks of pregnancy) – the earlier your baby is born, the greater the risk

- you have previously had a baby who developed a group B Strep infection

- you have had a high temperature (or other signs of infection) during labour

- you have had any group B Strep positive urine or swab test in this pregnancy

- your waters have broken more than 24 hours before your baby is born

Late-onset group B Strep infection (developing in babies aged 7-90 days) is less common than early-onset GBS infection and is more likely if:

- your baby is born preterm (before 37 weeks of pregnancy)

- you have had group B Strep positive test in this pregnancy

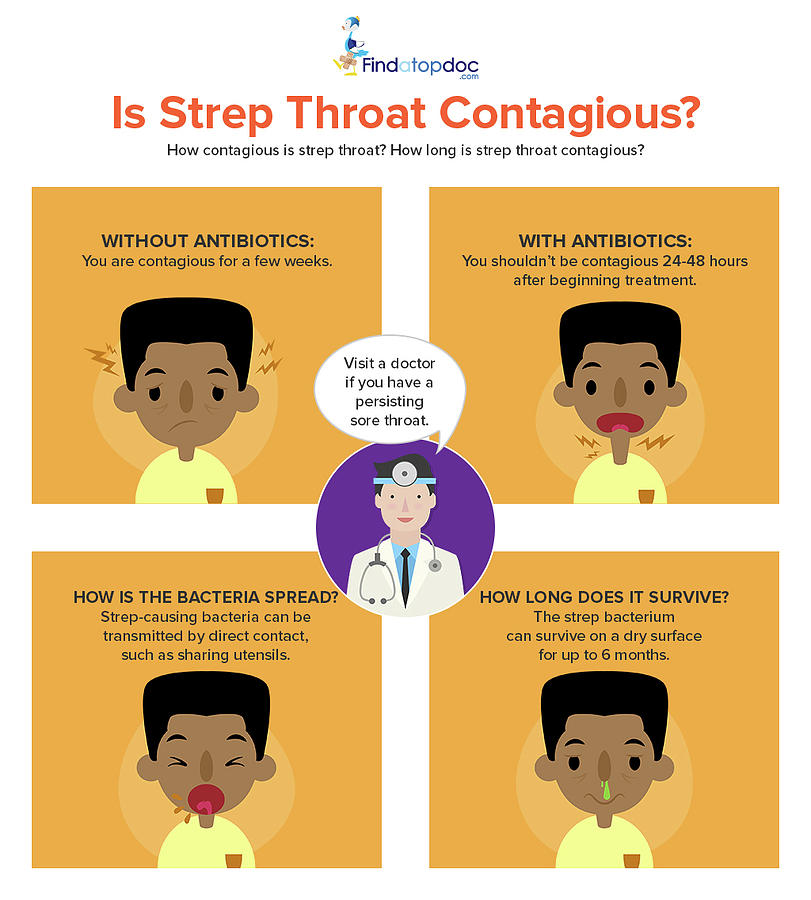

Most early-onset group B Strep infection can be prevented by giving intravenous antibiotics in labour to women whose babies are at raised risk of developing the infection. At present, there are no known methods to prevent late-onset GBS infection.

At present, there are no known methods to prevent late-onset GBS infection.

- A urine infection caused by group B Strep should be treated with antibiotic tablets straight away and you should also be offered intravenous (IV) antibiotics during labour.

- You should be offered IV antibiotics during labour if you have had a GBS-positive swab or urine test from an NHS or other accredited laboratories (see www.gbss.org.uk/test).

- If you have previously had a baby who was diagnosed with GBS infection, you should be offered IV antibiotics when you are in labour.

- If GBS was found in a previous pregnancy and your baby was unaffected, you can have a specific swab test (known as the ECM test) to see whether you are carrying GBS when you are 35-37 weeks pregnant. If the test result is positive, you will be offered antibiotics in labour. If the ECM test result is negative at this point, then the risk of your baby developing early-onset GBS infection is low and you may choose not to have antibiotics.

- If your waters break after 37 weeks of your pregnancy and you are known to carry GBS, you will be offered induction of labour straight away. This is to reduce the time that your baby is exposed to GBS before birth. You should also be offered IV antibiotics.

- Even if you are not known to carry GBS, if you develop any signs of infection in labour, you will be offered IV antibiotics that will treat a wide range of infections including GBS.

- If your labour starts before 37 weeks of your pregnancy, your healthcare professional will recommend that you have IV antibiotics even if you are not known to carry GBS.

At present, there are no known methods to prevent late-onset GBS infection, so knowledge of the typical signs of infection is vital.

If you are worried about your baby, you should urgently contact your healthcare professional and mention any history of GBS when you do.

Download a copy of this leaflet

If you have any questions about Group B Strep, please call our helpline

Mon-Fri 9am-5pm

0330 120 0796

Or email us at info@gbss. org.uk

org.uk

Related pages

Where to order a group B Strep test

What does my test result mean?

After your baby is born

Group B Strep In Pregnancy: Test, Risks & Treatment

Overview

What is group B strep?

Group B strep infection (also GBS or group B Streptococcus) is caused by bacteria typically found in a person's vagina or rectal area. About 25% of pregnant people have GBS, but don't know it because it doesn't cause symptoms. A pregnant person with GBS can pass the bacteria to their baby during vaginal delivery. Infants, older adults or people with a weakened or underdeveloped immune system are more likely to develop complications from group B strep.

Most newborns who get GBS don't become sick. However, the bacteria can cause severe and even life-threatening infections in a small percentage of newborns. Healthcare providers screen for group B strep as part of your routine prenatal care. If you test positive, your provider will treat you with antibiotics.

If you test positive, your provider will treat you with antibiotics.

How do you get group B strep?

GBS bacteria naturally occur in areas of your body like your intestines and genital and urinary tracts. Adults can't get it from person-to-person contact or from sharing food or drinks with an infected person. Experts aren't entirely sure why the bacteria spreads, but they know that it’s potentially harmful in babies and people with weakened immune systems.

When do you get tested for group B strep?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine screening for group B strep in all pregnancies. You're screened for GBS between 36 and 37 weeks of pregnancy. Group B strep testing involves your provider taking a swab of your vagina and rectum and then sending it to a lab for analysis.

Can Group B strep affect a developing fetus?

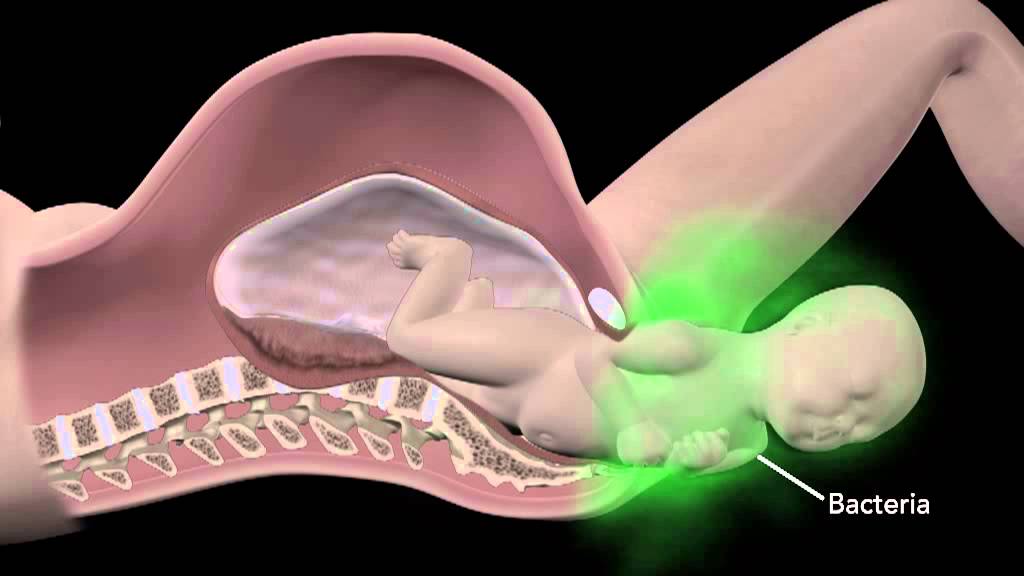

GBS doesn't affect the fetus baby while it's still inside your uterus. However, your baby can get GBS from you during labor and delivery. Taking antibiotics for GBS reduces your chances of passing it to your baby.

Taking antibiotics for GBS reduces your chances of passing it to your baby.

How does a baby get GBS?

There are two main types of Group B strep in babies:

- Early-onset infection: Most (75%) babies with GBS become infected in the first week of life. GBS infection is usually apparent within a few hours after birth. Premature babies face greater risk if they become infected, but most babies who get GBS are full-term.

- Late-onset infection: GBS infection can also occur in infants one week to three months after birth. Late-onset infection is less common and is less likely to result in a baby's death than early-onset infection.

How common is GBS?

Group B strep screening during pregnancy has decreased the number of cases. According to the CDC, about 930 babies get early-onset GBS, and 1,050 get late-onset GBS. About 4% of babies who develop GBS will die from it.

Symptoms and Causes

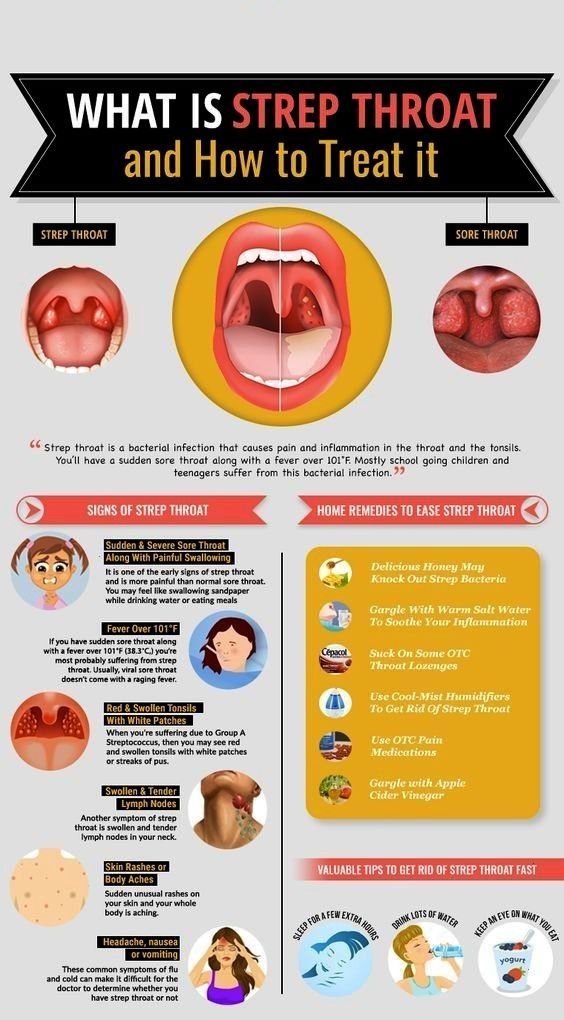

What are the symptoms of group B strep?

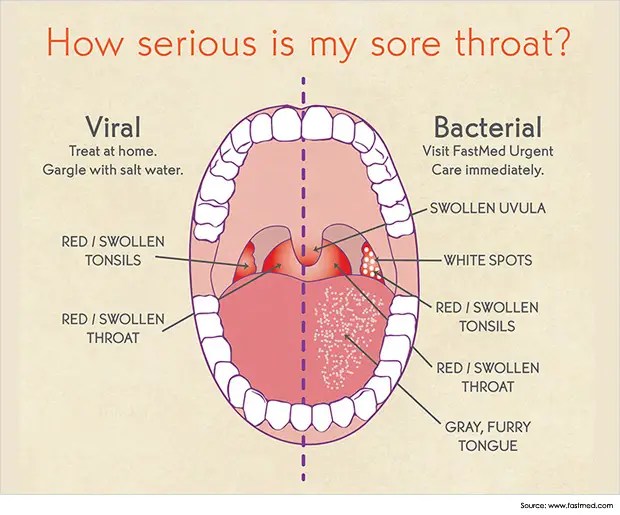

Most adults don't experience symptoms of group B strep. It can cause symptoms in older people or people with certain medical conditions, but this is rare. These symptoms include:

It can cause symptoms in older people or people with certain medical conditions, but this is rare. These symptoms include:

- Fever, chills and fatigue.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Chest pains.

- Muscle stiffness.

Newborns with GBS have symptoms like:

- Fever.

- Difficulty feeding.

- Irritability.

- Breathing difficulties.

- Lack of energy.

These symptoms can become serious quickly because newborns lack immunity. Group B strep infection can lead to severe problems like sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis in infants.

Can I pass group B strep to my partner?

Other people that live with you, including other children, aren't at risk of getting sick.

Diagnosis and Tests

Will I be tested for group B strep?

Yes, your healthcare provider will test you for GBS late in your pregnancy, around weeks 36 to 37.

Your obstetrician uses a cotton swab to obtain samples of cells from your vagina and rectum. This test doesn't hurt and takes less than a minute. Then, the sample is sent to a lab where it's analyzed for group B strep. Most people receive their results within 48 hours. A positive culture result means you're a GBS carrier, but it doesn't mean that you or your baby will become sick.

This test doesn't hurt and takes less than a minute. Then, the sample is sent to a lab where it's analyzed for group B strep. Most people receive their results within 48 hours. A positive culture result means you're a GBS carrier, but it doesn't mean that you or your baby will become sick.

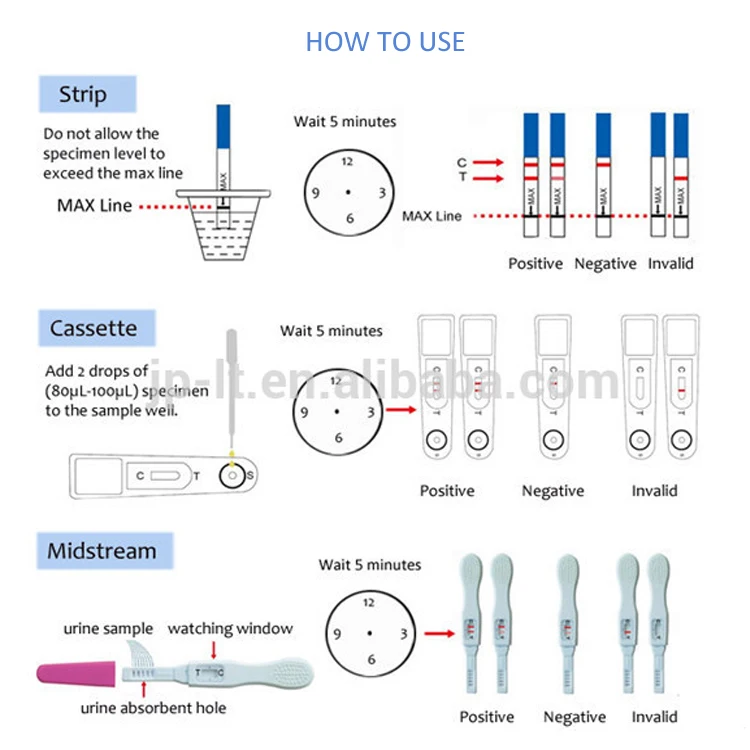

If you’re using a midwife, you might be given instructions on how to test yourself at home and submit the swab to a lab.

Is Group B strep an STD?

No, group B strep isn't an STD (sexually transmitted disease). The type of bacteria that causes GBS naturally lives in your vagina or rectum. It doesn't cause symptoms for most people.

Management and Treatment

What happens if you test positive for group B strep during pregnancy?

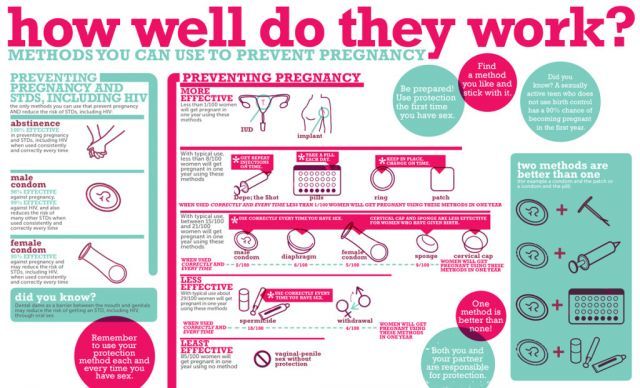

Healthcare providers prevent GBS infection in your baby by treating you with intravenous (IV) antibiotics during labor and delivery. The most common antibiotic to treat group B strep is penicillin or ampicillin. Giving you an antibiotic at this time helps prevent the spread of GBS from you to your newborn. It's not effective to treat GBS earlier than at delivery. The antibiotics work best when given at least four hours before delivery. About 90% of infections are prevented with this type of treatment.

It's not effective to treat GBS earlier than at delivery. The antibiotics work best when given at least four hours before delivery. About 90% of infections are prevented with this type of treatment.

One exception to the timing of treatment is when GBS is detected in urine. When this is the case, oral antibiotic treatment begins when GBS is identified (regardless of the stage of pregnancy). Antibiotics should still be given through an IV during labor.

Any pregnant person who has previously given birth to a baby who developed a GBS infection or who has had a urinary tract infection in this pregnancy caused by GBS will also be treated during labor.

How is group B strep treated in newborns?

Some babies still get GBS infections despite testing and antibiotic treatment during labor. Healthcare providers might take a sample of the baby's blood or spinal fluid to see if the baby has GBS infection. If your baby has GBS, they're treated with antibiotics through an IV.

Prevention

How can I reduce my risk of group B strep?

Anyone can get GBS. Some people are at higher risk due to certain medical conditions or age. The following factors increase your risk for having a baby born with group B strep:

Some people are at higher risk due to certain medical conditions or age. The following factors increase your risk for having a baby born with group B strep:

- You tested positive for GBS.

- You develop a fever during labor.

- More than 18 hours pass between your water breaking and your baby being born.

- You have medical conditions like diabetes, heart disease or cancer.

Getting screened for GBS and taking antibiotics (if you're positive) is the best way to protect your baby from infection.

Outlook / Prognosis

What are long term problems of Group B strep in newborns?

Infants with GBS can develop meningitis, pneumonia or sepsis. These illnesses can be life-threatening. Most infants don't develop any long-term issues; however, about 25% of babies with meningitis caused by GBS develop cerebral palsy, hearing problems, learning disabilities or seizures.

Can I get tested for group B strep again?

No, once you test positive for GBS, you're considered positive for the rest of your pregnancy. You will not get re-tested.

You will not get re-tested.

Do I need treated for group B strep if I am having a c-section?

No, you don't need antibiotics if you're having a c-section delivery. However, you'll still be tested for GBS because labor could start before your scheduled c-section. If your water breaks and you're GBS positive, your baby is at risk of contracting the disease.

Living With

When should I see my healthcare provider if I’m positive for group B strep?

In some cases, GBS causes infections during pregnancy. Symptoms of infection include fever, pain and increased heart rate. Let your provider know if you have any of those symptoms as it could lead to preterm labor.

GBS can also cause urinary tract infection (UTI), which requires oral antibiotics.

Talk to your provider about what you can expect during labor and delivery if you have group B strep.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Try not to panic if your healthcare provider tells you you're positive for group B strep during pregnancy. It's caused by bacteria that occur naturally in your body, not by anything you did wrong. The chances of you passing group B strep to your baby are quite low, especially if you take antibiotics during labor. Talk to your provider about group B strep and share any concerns you have. In most cases, testing positive for GBS causes no problems, and your baby is healthy.

It's caused by bacteria that occur naturally in your body, not by anything you did wrong. The chances of you passing group B strep to your baby are quite low, especially if you take antibiotics during labor. Talk to your provider about group B strep and share any concerns you have. In most cases, testing positive for GBS causes no problems, and your baby is healthy.

strept. Agalactiae (group B streptococci) (determination in the material by PCR method)

Article: 00162

Cost of analysis

in the online store: 7% discount!

Plain

577 rublesLab:

Regular

620 rubles

the price does not include the cost of taking biological material

Add to Basket

Analysis results ready

Regular*: 1-2 business days

Analysis submission date:

Completion date:

*excluding the day of delivery.

Where and when you can rent

- Buninskaya alley

- Voykovskaya

- Dubrovka

- Maryino

- Novokuznetskaya

- Podolsk

- Weekdays: from 7.45 to 21.00

- Weekends: from 8.45 to 17.00

Changes in work schedule

Preparation for analysis

General recommendations for testing

For women: Taken after menstruation. Sexual life, douching, vaginal showers, the use of tampons, suppositories and other local preparations are prohibited for 24 hours. It is advisable not to take a bath. Only the external toilet of the genitals is allowed. It is advisable to take smears for infections and crops no earlier than 3 weeks after taking antibiotics (for any reason). This does not apply to the diagnosis of viral infections. For men: Do not urinate for 1.5-2 hours. It is advisable to take smears for infections and crops no earlier than 3 weeks after taking antibiotics (for any reason). This does not apply to the diagnosis of viral infections.

This does not apply to the diagnosis of viral infections.

Biomaterial collection

- Swab collection

Methods and tests

PCR (polymerase chain reaction). Qualitative

Files

Download a sample of the result of the analysis

What is it for

Group B streptococci (Streptococcus agalactiae) are bacteria found in the lower intestines of 10-35% of healthy men and in the vagina and/or lower intestines of 10-35% of healthy women. These bacteria are a normal part of the human microflora. Although group B streptococcus is generally safe for adults, it can cause serious complications during pregnancy and severe illness in newborns. Also, group B streptococcus can affect people with a weakened immune system, chronic diseases, and the elderly.

How can a newborn become infected with streptococcus

Most infections occur during childbirth. Possible infection with premature rupture of the membranes. It is possible that infection can also occur through intact fetal membranes.

Possible infection with premature rupture of the membranes. It is possible that infection can also occur through intact fetal membranes.

Risk factors for the development of streptococcal infection

- presence of streptococcus on examination in vaginal discharge or urine;

- rupture of membranes;

- fever during labor;

- maternal age less than 20 years;

- streptococcal infection of the newborn in past births.

Streptococcal infection can threaten a newborn

First of all, infection with streptococcus is dangerous not for the mother, but for the baby.

- Inflammation of the lungs (pneumonia)

- Inflammation of the meninges - meningitis

- Streptococci may cause septic complications

- If infected before delivery, may cause premature birth, miscarriage, stillbirth.

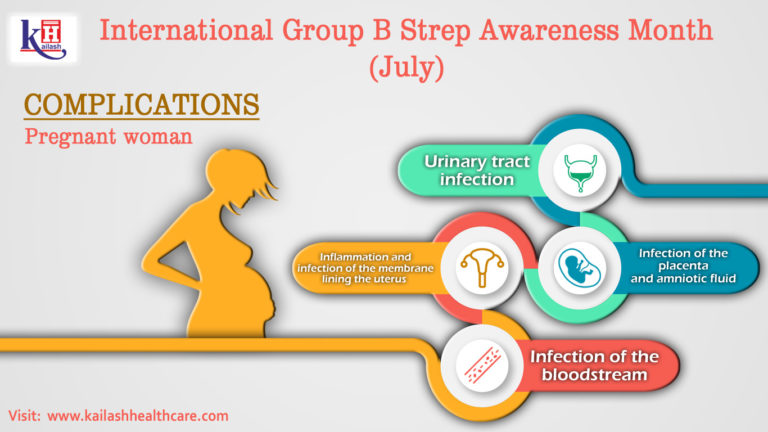

What disorders can be caused by group B streptococcus in a pregnant woman and after childbirth

Usually streptococcus does not affect healthy adults, however, in rare cases, it can cause infectious complications in a pregnant woman:

- Urinary tract infection

- Infection of the placenta and amniotic fluid (chorioamnionitis)

- Bacteremia (circulation of bacteria in the blood)

- Terrible complication - sepsis

- Rarely, after childbirth, streptococcus can cause inflammation and infection of the lining of the uterine cavity - endometritis

- Streptococcus can cause wound infection in women after caesarean section

Should pregnant women be tested?

The first examination is desirable to be done in the first trimester of pregnancy, especially if there have been miscarriages or premature births in the past. It is advisable to re-examine at 35-37 weeks of pregnancy.

It is advisable to re-examine at 35-37 weeks of pregnancy.

Testing is also recommended for elective caesarean section, even though the baby is not in contact with the birth canal.

How to get tested for streptococcus

Preliminary preparation for the delivery of the analysis is not required. An analysis for group B streptococcus is taken from the vagina with a special swab, which is placed in the environment and then analyzed in the laboratory by PCR.

What to do with the analysis results

If the test is negative, no action is required.

If you test positive for group B streptococcus, it does not mean that you or your child will definitely get sick. But the risk of infection in this case is higher. To prevent diseases of the child during childbirth or in case of premature outflow of water, antibiotics are prescribed prophylactically. Prescribing antibiotics earlier is not justified, as bacteria multiply rapidly and can become dangerous again.

Prescribing antibiotics earlier is not justified, as bacteria multiply rapidly and can become dangerous again.

Be sure to notify the attending physician of a positive result for group B streptococcus.

Streptococcus and breastfeeding Breastfeeding is not contraindicated in streptococcal infections. Follow normal hygiene rules (wash your hands and nipples).

Read more about streptococcal infection on the website of the Center for Immunology and Reproduction

Tags: Strept. Agalactiae (group B streptococcus), streptococcus, pregnancy, pregnancy tests

How to pass tests at the CIR Laboratories?

To save time, place an order for analysis in the Online Store ! Paying for an order online, you get a discount 7% for the entire order!

Do you have questions? Write to us or call +7 (495) 514-00-11. According to the analysis, you can ask a question on our forum and seek advice from a specialist.

Practice Guidelines for Counseling Pregnant Women with Group B Streptococcus | Pashchenko A.

A., Dzhokhadze L.S., Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Kotomina T.S., Efremov A.N.

A., Dzhokhadze L.S., Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Kotomina T.S., Efremov A.N. Introduction

In the clinical practice of an obstetrician-gynecologist, there are often problems associated with determining further tactics after receiving a urine culture result with a detected growth of colonies of group B streptococcus ( Streptococcus agalactiae ; group B streptococcus, GBS). In accordance with the clinical guidelines "Normal Pregnancy" (2020), the diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is made after receiving repeated results of urine culture (not earlier than 2 weeks after the first analysis) with an increase in colonies of bacterial agents in an amount > 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine in the absence of clinical symptoms [1], while it is noted that antibacterial treatment of detected bacteriuria reduces the risk of developing pyelonephritis, preterm labor (PR) and fetal growth retardation (FGR) [1, 2].

Given the proven risks of S. agalactiae -associated infectious complications for the unborn child and the pregnant woman herself, the doctor often shows caution when choosing further laboratory and drug tactics in such a patient.

agalactiae -associated infectious complications for the unborn child and the pregnant woman herself, the doctor often shows caution when choosing further laboratory and drug tactics in such a patient.

Detection of S. agalactiae antigen at 35–37 weeks pregnancy in the discharge of the vagina or cervical canal, according to the domestic protocol "Normal pregnancy" (2020), is an absolute indication for antibacterial prevention of early neonatal infection with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid [1]. However, the question of the advisability of using antibiotic therapy when colonies of S. agalactiae are detected in the urine of pregnant women in amounts <10 5 in 1 ml or on the epithelium of the genitourinary tract during pregnancy is still open.

Streptococcus agalactiae refers to β-hemolytic gram-positive cocci with virulence factors such as hemolysin and polysaccharide capsule that prevent bacterial phagocytosis. Among pregnant women, often asymptomatic rectovaginal carriage of S is noted. agalactiae is a conditional pathogen of vaginal microbiocenosis with a frequency of occurrence in the European population from 16% to 22% [3] and predominant bacterial colonization from the gastrointestinal tract. In the 1970s, a hypothesis was first formulated and a correlation was proven between perinatal morbidity, leading to early neonatal death, and persistence of S. agalactiae in pregnant women [4, 5]. The introduction of clinical guidelines on intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis into obstetric practice has reduced the incidence of neonatal sepsis due to maternal GBS carriage by 80% in the United States. According to the statistics of the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in a report for 2016, the frequency of development in the early neonatal period of meningitis and sepsis caused by bacterial agents from the group of β-hemolytic gram-positive S.

Among pregnant women, often asymptomatic rectovaginal carriage of S is noted. agalactiae is a conditional pathogen of vaginal microbiocenosis with a frequency of occurrence in the European population from 16% to 22% [3] and predominant bacterial colonization from the gastrointestinal tract. In the 1970s, a hypothesis was first formulated and a correlation was proven between perinatal morbidity, leading to early neonatal death, and persistence of S. agalactiae in pregnant women [4, 5]. The introduction of clinical guidelines on intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis into obstetric practice has reduced the incidence of neonatal sepsis due to maternal GBS carriage by 80% in the United States. According to the statistics of the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in a report for 2016, the frequency of development in the early neonatal period of meningitis and sepsis caused by bacterial agents from the group of β-hemolytic gram-positive S. agalactiae was 0.22 cases per 1000 deliveries, excluding stillbirths [6, 7].

agalactiae was 0.22 cases per 1000 deliveries, excluding stillbirths [6, 7].

S. agalactiae as a predictor of urinary tract infection, choriamnionitis and PR in pregnant women

Urinary tract infection is one of the most common extragenital pathologies in pregnant women [8]. The frequency of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy is determined at the level of 2% to 10% [7-11]. Current domestic clinical guidelines for laboratory and instrumental screening of normal pregnancy prescribe a single microbiological (cultural) study of an average portion of urine for bacterial pathogens in order to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria after 14 weeks. gestation [1].

The lack of timely antibacterial pharmacotherapy of asymptomatic bacteriuria in 35% of cases leads to the development of an acute infectious process - pyelonephritis of pregnant women [7, 11, 12]. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of "Pyelonephritis of pregnancy" is made on the basis of a positive result of urine culture for bacterial pathogens, the presence of severe fever with chills and increased sweating, complaints of pain in the lower back with irradiation along the ureter to the thigh or abdomen and back, nausea / vomiting, pain on palpation of the costovertebral angle, as well as with a positive symptom of Pasternatsky. The predominant bacterial agent initiating an acute infectious process in the urinary tract of pregnant women is Escherichia coli ; S. agalactiae colonies are identified on average in 2.1–30% of cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women [7, 13].

The predominant bacterial agent initiating an acute infectious process in the urinary tract of pregnant women is Escherichia coli ; S. agalactiae colonies are identified on average in 2.1–30% of cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women [7, 13].

The presence of S. agalactiae in urine culture can be considered as a marker of colonization of the anogenital area of a pregnant woman, which is associated with the risk of infection of the amniotic fluid, placenta and / or decidua and the development of chorioamnionitis, or intra-amniotic infection [14]. S. agalactiae is the most common bacterial agent associated with the development of chorioamnionitis, diagnosed on the basis of a hyperthermic reaction in a patient, complaints of soreness in the pregnant uterus, symptoms of tachycardia of the pregnant woman and fetus (increased basal rhythm of the CTG curve), purulent discharge from the cervix uterus and laboratory blood test data with neutrophilic leukocytosis and an increase in the level of C-reactive protein [14, 15].

For the first time, the association of asymptomatic bacteriuria caused by the presence of S. agalactiae colonies in urine with the risk of developing PR was described by E. Kass et al. in 1960 [16]. Subsequently, this hypothesis was developed in their studies by M. Mølle et al. [17], stating that premature rupture of membranes and PT are more common in the group of patients who are GBS carriers. However, further studies by P. Meis et al. [18], with the adjustment of demographic factors and additional statistical processing of the data, revealed the lack of sufficient statistically significant evidence of the relationship between asymptomatic bacteriuria and the presence of GBS colonies and a higher risk of developing PR.

Previously published studies on this issue have contributed to the formation of the practice of irrational pharmacotherapy of asymptomatic pregnant women with negligible concentrations of GBS in urine cultures in many international scientific obstetric communities [19].

In order to optimize and develop an evidence-based counseling program for pregnant women with rectovaginal carriage of S. agalactiae , approaches to laboratory diagnostics and drug therapy strategies in domestic obstetric and gynecological practice, we searched for medical publications in the MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library databases. . The selection criteria were: publications in English for 2015-2020, which present the results of randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis; recommendations for drug therapy and studies on the relationship between S. agalactiae - associated bacteriuria and antibiotic resistance. The following search terms were used: streptococcal infection, Streptococcus agalactiae , bacteriuria, pregnancy, antibiotic resistance, maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Nine articles [12, 13, 20–26] met the selection criteria (see table).

We conducted a literature review in order to develop optimal tactics for the management (observation and treatment) of pregnant women who are carriers of S. agalactiae depending on the concentration of the bacterial agent in the urine culture. An analysis of the clinical recommendations of international and national medical communities has shown different approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria associated with the presence of S. agalactiae colonies [6, 11]. Previously published scientific studies have generally supported the strategy of antibiotic therapy in patients carrying S. agalactiae at any concentration and at any stage of pregnancy to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality [16, 17, 27], but the fact of GSB recolonization was noted. urethral epithelium in most pregnant women within a short time after its complete elimination [20].

agalactiae depending on the concentration of the bacterial agent in the urine culture. An analysis of the clinical recommendations of international and national medical communities has shown different approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria associated with the presence of S. agalactiae colonies [6, 11]. Previously published scientific studies have generally supported the strategy of antibiotic therapy in patients carrying S. agalactiae at any concentration and at any stage of pregnancy to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality [16, 17, 27], but the fact of GSB recolonization was noted. urethral epithelium in most pregnant women within a short time after its complete elimination [20].

The current data presented by us from the latest retrospective and prospective studies conducted with additional statistical processing and control of confounding errors did not demonstrate a significantly significant association between the risk of PR, a higher incidence of pyelonephritis and postpartum endometritis in pregnant women with bacteriuria associated only with the presence of S colonies. agalactiae in the absence of other bacterial agents [24–26]. J. Henderson et al. [10] in their latest publications draw attention to the individual microbiome for each woman, due to the opportunistic flora of the vagina, and its protective role for both the pregnant woman and the newborn.

agalactiae in the absence of other bacterial agents [24–26]. J. Henderson et al. [10] in their latest publications draw attention to the individual microbiome for each woman, due to the opportunistic flora of the vagina, and its protective role for both the pregnant woman and the newborn.

The updated recommendations of ACOG and the American Society for Infectious Diseases prescribe antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria with a concentration of bacterial agents of at least 10 5 CFU/ml [2, 28–30], which is fully consistent with current domestic recommendations [1].

Taking into account the results of a systematic review of the latest publications and an analysis of current clinical recommendations from various world medical communities, we have developed a practical guide for counseling pregnant women with GBS colonization of the genitourinary system in various clinical situations for outpatient and inpatient obstetrician-gynecologists.

Clinical situation No. 1

1

Real-time PCR detection of vaginal discharge or cervical canal by microbiological examination of S. agalactiae colonies.

Does not require antibacterial treatment at the time of detection in asymptomatic patients.

Comment . S. agalactiae refers to opportunistic facultative anaerobic microorganisms of the vaginal and intestinal microbiocenosis. Drug treatment with positive results of microbiological studies (crops) in patients with no e0lob and clinical symptoms is an erroneous strategy, in addition, it increases the risk of antibiotic resistance.

Etiotropic drug therapy is prescribed only in case of symptoms of bacterial or mixed vaginosis, caused, among other things, by the presence of S. agalactiae colonies and other bacterial agents, in order to relieve symptoms and reduce the risk of PR. The main symptoms of bacterial / mixed vaginosis in the presence of a predominantly anaerobic pathogenic flora are: itching and burning in the vagina, profuse discharge from the genital tract with an unpleasant odor, "key" cells in smears, a decrease in pH values in the vagina and a decrease in the number of lactobacilli.

It is necessary to record the results of microbiological examination / culture as the carriage of S. agalactiae colonies during pregnancy in the patient's exchange record.

Comment . Even a single anamnestic documented fact of the presence of S. agalactiae colonies in the urogenital tract of a pregnant woman indicates the carriage of β-hemolytic streptococcus with a risk of intranatal infection and is an indication for antibiotic prophylaxis during childbirth or when amniotic fluid is discharged in order to reduce perinatal mortality.

Vaginal-rectal screening between the 35th and 37th weeks is optional.

Comment . ACOG recommends that vaginal-rectal screening not be performed between 36 0/7 and 37 6/7 weeks if S. agalactiae colonies have already been isolated in the vaginal or cervical discharge during pregnancy and antibacterial prophylaxis of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor activity [30].

Antibiotic prophylaxis during childbirth is indicated.

Comment . Considering the documented presence of S. agalactiae colonies in vaginal discharge or cervical canal, for this group of pregnant women it is mandatory to prescribe antibacterial prophylaxis of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid in order to reduce perinatal mortality [29, 30].

Antibiotic prophylaxis in childbirth should be carried out even after a full course of antibiotic treatment of S. agalactiae -associated infections during pregnancy, since the fact of repeated recolonization of the genitourinary tract after antibacterial exposure after a few days has been proven.

Clinical situation #2

Detection in urine culture of colonies S. agalactiae in any titer.

Repeat urine culture after 2 weeks. since the first analysis.

Repeated detection in the urine culture of a clinically significant concentration of bacterial agents, including colonies S. agalactiae (10 5 and more in 1 ml of the average portion of urine).

agalactiae (10 5 and more in 1 ml of the average portion of urine).

A diagnosis of asymptomatic bacteriuria is made.

Comment . In accordance with the clinical guidelines "Normal Pregnancy" (2020), the diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is made after receiving repeated urine culture with the growth of colonies of bacterial agents in the amount of > 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine (including the presence of S. agalactiae and / or other bacterial agents in the urine, for example E. coli ) in the absence of clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is an absolute indication for the appointment of antibiotic therapy in order to prevent the possible development of pyelonephritis, PR and IGR [12]. However, it should be noted that the presence of only one species of colonies S. agalactiae in urine, even in clinically significant amounts (> 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine) does not require an increase in the dose and the frequency of taking antibacterial drugs more than the standard weekly course [24-26].

Vaginal-rectal screening between the 35th and 37th weeks is not necessary, since the isolation of S. agalactiae colonies in the urine or vaginal or cervical canal has already been noted during pregnancy.

Antibiotic prophylaxis during childbirth is indicated.

Comment . Despite the full course of antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria, repeated recolonization of the genitourinary tract S. agalactiae in a small amount can occur within a few days, so it is mandatory for this group of pregnant women to prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic water to improve perinatal outcomes [29, thirty].

Detection in the primary or repeated urine culture after 2 weeks. low concentrations of S. agalactiae and other bacterial agents (less than 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine or less than 100,000 CFU / ml).

The diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is invalid, and antibacterial therapy at the time of detection in the urine culture of pregnant women of a clinically insignificant concentration of S. agalactiae and other bacterial agents is inappropriate.

agalactiae and other bacterial agents is inappropriate.

Comment . The presence of bacteriuria with a low concentration of S. agalactiae colonies (less than 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine or less than 10 5 CFU / ml) indicates maternal anogenital colonization of the urinary tract.

Given the low incidence of pyelonephritis in pregnant women, there is a significantly insignificant risk of developing PR, chorioamnionitis and postpartum endometritis associated with the presence of S. agalactiae in urine culture at low concentrations (less than 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine or less than 100,000 CFU / ml), therapy in this clinical situation is irrational and increases the risk of developing resistance to the main groups of antibiotics [10, 24– 26, 31, 32].

It is necessary to document the results of the urine culture of the pregnant woman as the carriage of S. agalactiae colonies during pregnancy in the patient's exchange record.

Vaginal-rectal screening between the 35th and 37th weeks is not necessary, since the isolation of S. agalactiae colonies in the urine or vaginal or cervical canal has already been noted during pregnancy.

Antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown in childbirth with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid in order to reduce perinatal mortality [29, 30].

Clinical situation No. 3

Detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) at 35–37 weeks pregnancy in the discharge of the vagina or cervical canal.

An absolute indication for antibiotic prophylaxis with the onset of labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid.

Comment . If there is no anamnestic data on the detection of colonies in the patient's exchange card S. agalactiae in the urogenital tract during pregnancy, screening is carried out for the detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) in the discharge of the cervical canal and / or vaginal contents at 35–37 weeks. pregnancy, according to domestic clinical guidelines [1].

agalactiae ) in the discharge of the cervical canal and / or vaginal contents at 35–37 weeks. pregnancy, according to domestic clinical guidelines [1].

If screening is positive, antibiotic prophylaxis should be carried out with the onset of labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid in order to reduce perinatal mortality.

Comment . In the absence of anamnestic data on the detection of colonies S. agalactiae in the genitourinary tract during pregnancy and data on the results of detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) in 35-37 weeks in the patient's exchange card, pregnancy, as well as in the absence of previous screening (for example, the gestational age is less than 35 weeks), an express test for the detection of S. agalactiae antigen should be performed in the emergency department of the hospital with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid to resolve the issue of conducting antibiotic prophylaxis.

With a planned operative delivery and the absence of data on the detection of colonies S. agalactiae during pregnancy, the results of screening for the detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) at 35–37 weeks. gestation in the discharge of the vagina and cervical canal may be necessary for a neonatologist in order to differentially diagnose infectious diseases in the early neonatal period.

Principles of rational pharmacotherapy for pregnant women with S. agalactiae

For the pharmacotherapy of pregnant women with S. agalactiae carriage, β-lactam antibiotics from the group of semi-synthetic penicillins are used. With a burdened allergic history with the occurrence of hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin antibiotics, culture is required to determine the sensitivity of S. agalactiae colonies to second-line antimicrobials.

Comment . In clinical practice, antibiotics from the group of protected penicillins are most often used as the drug of choice: a combination of a semi-synthetic β-lactam antibiotic and a β-lactamase inhibitor (ampicillin + sulbactam). The appointment of a combination of ampicillin + clavulanic acid is possible only after 34 weeks. gestation due to the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis due to exposure to clavulanic acid on fetal enterocytes at this stage of pregnancy.

The appointment of a combination of ampicillin + clavulanic acid is possible only after 34 weeks. gestation due to the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis due to exposure to clavulanic acid on fetal enterocytes at this stage of pregnancy.

Second-line drugs include first-generation cephalosporins or clindamycin from the lincosamide group. Given the increase in resistance to antibacterial drugs from the group of cephalosporins and lincosamides, nitrofurantoin can be prescribed in the II and III trimesters up to 36 weeks. gestation due to increased risks of developing neonatal jaundice in newborns when taking the drug 7 days before delivery [1, 31, 32].

Intranatal antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with colonies S. agalactiae in the urogenital tract

For the purpose of antibacterial prevention of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor activity or with the outflow of amniotic fluid, first- or second-line drugs are prescribed intravenously every 6-8 hours, while the first dose of the drug is administered in a double dosage (with intravenous administration of antibiotics, the concentration of colonies of β-hemolytic streptococcus per epithelium of the urinary tract decreases sharply within about 2 hours).

Intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis is the main strategy to reduce the risk of streptococcal infection in the neonatal period. A multivalent polysaccharide protein conjugate vaccine is currently being developed, which may

'edo, will become an alternative to primary intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis of early neonatal infection and improve perinatal outcomes [32].

Principles of rational pharmacotherapy for patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria

In 2016 and 2018 WHO has issued recommendations on a 7-day antibiotic regimen for all pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria to prevent drug resistance, risk of preterm birth, and low birth weight newborns. The WHO recommendations were based on data from a Cochrane Library review that included 14 studies involving more than 2,000 people with a concentration of bacterial agents greater than 10 5 in the average portion of urine [12]. The presence in the urine of only one type of colony - S. agalactiae - in clinically significant amounts (> 10 5 in 1 ml of the average portion of urine) does not require an increase in the dose and frequency of taking antibacterial drugs more than the standard weekly course.

agalactiae - in clinically significant amounts (> 10 5 in 1 ml of the average portion of urine) does not require an increase in the dose and frequency of taking antibacterial drugs more than the standard weekly course.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic rectovaginal carriage of S. agalactiae in pregnant women is significantly associated with severe infectious complications in the early neonatal period (meningitis, neonatal sepsis), therefore, a clear balanced approach to the management of such women is required, which would ensure the birth of healthy children and would not increase the risks associated with increasing antibiotic resistance S. agalactiae , under the condition of inevitable re-colonization of the genitourinary system a few days after the administration of antibiotics. Our analysis of the current clinical recommendations of the world professional medical communities is reflected in the practical recommendations presented in this article on the optimal tactics for monitoring and treating pregnant women who are carriers of S. agalactiae in the domestic practice of an obstetrician-gynecologist.

agalactiae in the domestic practice of an obstetrician-gynecologist.

Information about authors:

Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Pashchenko — Clinical Postgraduate Student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Russian National Research Medical University named after I.I. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID iD 0000-0003-0202-2740.

Dzhokhadze Lela Sergeevna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Russian National Research Medical University named after I.I. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID ID 0000-0001-5389-7817.

Dobrokhotova Yuliya Eduardovna — Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty of the Russian National Research Medical University. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID iD 0000-0002-7830-2290.

N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID iD 0000-0002-7830-2290.

Kotomina Tatyana Sergeevna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the maternity ward of the branch No. 1 of the GBUZ "City Clinical Hospital No. 52 DZM"; 123182, Russia, Moscow, st. Sosnovaya, d. 11; ORCID iD 0000-0002-5660-2380.

Efremov Alexander Nikolaevich - obstetrician-gynecologist of the postpartum department of the branch No. 1 GBUZ "City Clinical Hospital No. 52 DZM"; 123182, Russia, Moscow, st. Sosnovaya, 11.

Contact information: Pashchenko Alexander Alexandrovich, e-mail: [email protected].

Financial transparency: none of the authors has a financial interest in the submitted materials or methods.

No conflict of interest.

Article received on 04/05/2021.

Received after peer review on 04/28/2021.

Accepted for publication on May 25, 2021.

About the authors:

Aleksandr A. Pashchenko — postgraduate student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University; 1, Ostrovityanov str., Moscow, 117437, Russian Federation; ORCID iD 0000-0003-0202-2740.

Lela S. Dhokhadze—C. Sc. (Med.), assistant of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University; 1, Ostrovityanov str., Moscow, 117437, Russian Federation; ORCID ID 0000-0001-5389-7817.

Yuliya E. Dobrokhotova - Dr. Sc. (Med.), Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University; 1, Ostrovityanov str., Moscow, 117437, Russian Federation; ORCID ID 0000-0002-7830-2290.

Tatyana S. Kotomina - C.