How can we teach child

New skills for kids & behaviour management

Helping children learn new skills as part of behaviour management

When children can do the things they want or need to do, they’re more likely to cooperate. They’re also less likely to get frustrated and behave in challenging ways. This means that helping children learn new skills can be an important part of managing behaviour.

When children learn new skills, they also build independence, confidence and self-esteem. So helping children learn new skills can be an important part of supporting overall development too.

Here’s an example: if your child doesn’t know how to set the table, they might refuse to do it – because they can’t do it. But if you show your child how to set the table, they’re more likely to do it. They’ll also get a sense of achievement and feel good about helping to get your family meal ready.

There are 3 key ways you can help children learn everything from basic self-care to more complicated social skills:

- modelling

- instructions

- step by step.

Remember that skills take time to develop, and practice is important. But if you have any concerns about your child’s behaviour, development or ability to learn new skills, see your GP or your child and family health nurse.

When you’re helping your child learn a skill, you can use more than one teaching method at a time. For example, your child might find it easier to understand instructions if you also break down the skill or task into steps. Likewise, modelling might work better if you give instructions at the same time.

Modelling

Through watching you, your child learns what to do and how to do it. When this happens, you’re ‘modelling’.

Modelling is usually the most efficient way to help children learn a new skill. For example, you’re more likely to show rather than tell your child how to make a bed, sweep a floor or throw a ball.

Modelling can work for social skills. Prompting your child with phrases like ‘Thank you, Mum’, or ‘More please, Dad’ is an example of this.

You can also use modelling to show your child skills and behaviour that involve non-verbal communication, like body language and tone of voice. For example, you can show how you turn to face people when you talk to them, or look them in the eyes and smile when you thank them.

Children also learn by watching other children. For example, your child might try new foods with other children at preschool even though they might not do this at home with you.

How to make modelling work well

- Get your child’s attention, and make sure your child is looking at you.

- Move slowly through the steps of the skill so that your child can clearly see what you’re doing.

- Point out the important parts of what you’re doing – for example, ‘See how I am …’. You might want to do this later if you’re modelling social skills like greeting a guest.

- Give your child plenty of opportunities to practise the skill once they’ve seen you do it – for example, ‘OK, now you have a go’.

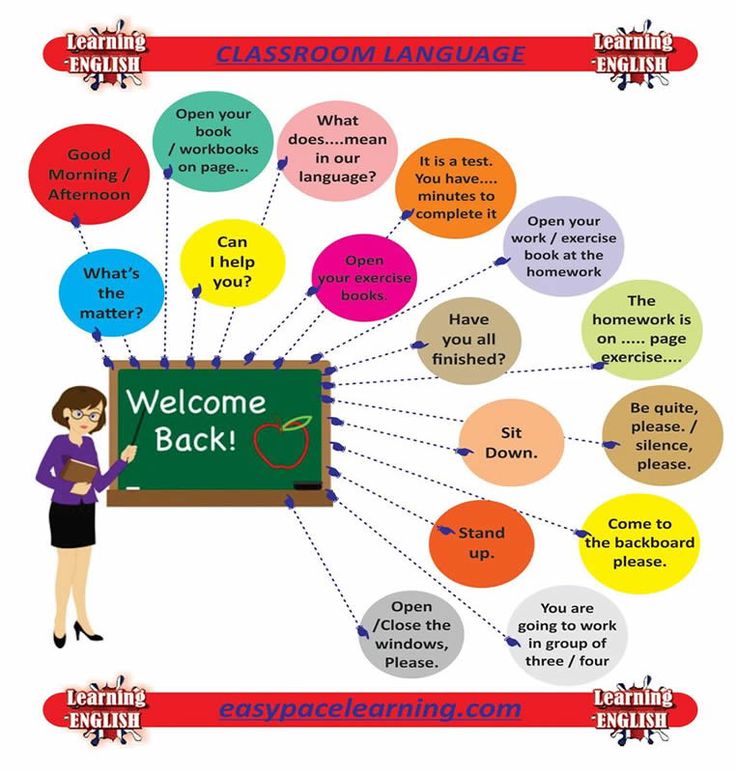

Instructions

You can help your child learn how to do something by explaining what to do or how to do it.

How to give good instructions

- Give instructions only when you have your child’s attention.

- Use your child’s name and encourage your child to look at you while you speak.

- Get down to your child’s physical level to speak.

- Remove any background distractions like the TV.

- Use language that your child understands. Keep your sentences short and simple.

- Use a clear, calm voice.

- Use gestures to emphasise things that you want your child to notice.

- Gradually phase out your instructions and reminders as your child gets better at remembering how to do the skill or task.

A picture that shows your child what to do can help them understand the instructions. Your child can check the picture when they’re ready to work through the instructions independently. This can also help children who have trouble understanding words.

Sometimes your child won’t follow instructions. This can happen for many reasons. Your child might not understand. Your child might not have the skills to do what you ask every time. Or your child just might not want to do what you’re asking. You can help your child learn to cooperate by balancing instructions and requests.

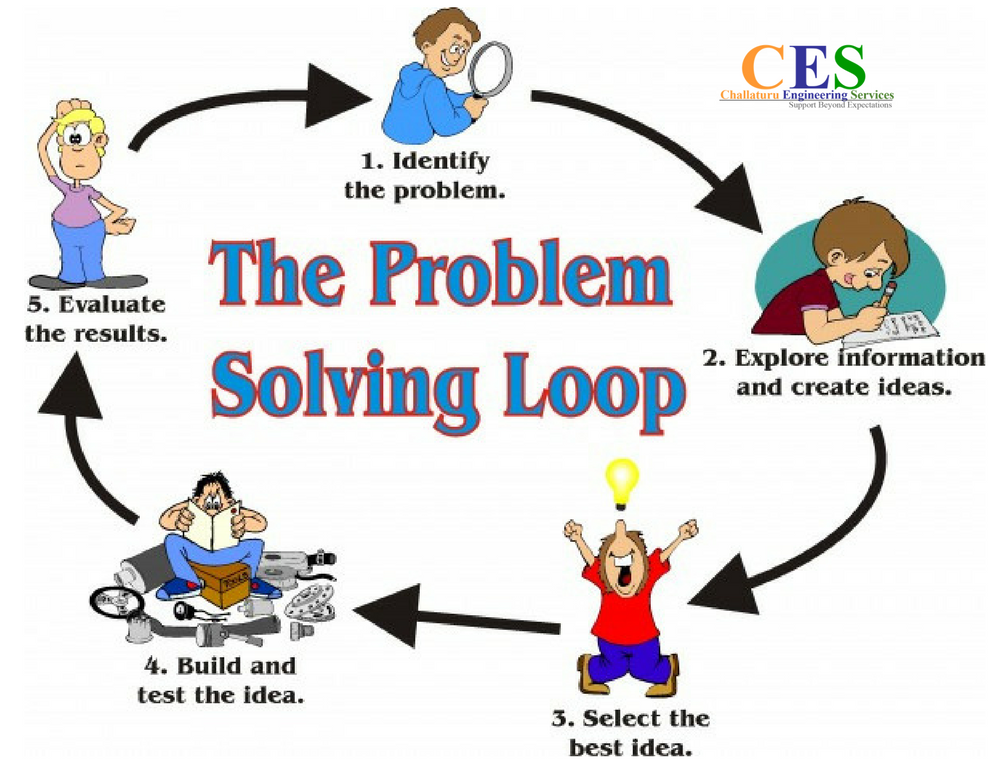

Step-by-step guidance: breaking down tasks

Some skills or tasks are complicated or involve a sequence of actions. You can break these skills or tasks into smaller steps. The idea is to help children learn the steps that make up a skill or task, one at a time.

How to do step-by-step guidance

- Start with the easiest step if you can.

- Show your child the step, then let them try it.

- Give your child more help with the rest of the task or do it for them.

- Give your child opportunities to practise the step.

- When your child can do the step reliably and without your help, teach them the next step, and so on.

- Keep going until your child can do the whole skill or task for themselves.

An example of step-by-step guidance

Here’s how you could break down the task of getting dressed:

- Get clothes out.

- Put on underpants.

- Put on socks.

- Put on shirt.

- Put on pants.

- Put on a jumper.

You could break down each of these steps into parts as well. This can help if a task is complex or if your child has learning difficulties. For example, ‘Put on a jumper’ could be broken down like this:

- Face the jumper the right way.

- Pull the jumper over your head.

- Put one arm through.

- Put your other arm through.

- Pull the jumper down.

Forwards or backwards steps?

You can help your child learn steps by moving:

- forwards – teaching your child the first step, then the next step and so on

- backwards – helping your child with all the steps until the last step, then teaching the last step, then the second last step and so on.

Learning backwards has some advantages. Your child is less likely to get frustrated because it’s easier and quicker to learn the last step. Also the task is finished as soon as your child completes the step. Often the most rewarding thing about a job or task is getting it finished!

In the earlier example, you might teach your child to get dressed by starting with a jumper. You’d help your child get dressed until it came to the final step – the jumper.

You might help your child put the jumper over their head and put their arms in – then you might let your child pull the jumper down by themselves. Once your child can do this, you might encourage your child to put their arms through by themselves and then pull the jumper down. This would go on until your child can do each step, so they can do the whole task for themselves.

When your child is learning a new physical skill like getting dressed, it can help to put your hands over your child’s hands and guide your child through the movements. Phase out your help as your child begins to get the idea, but keep saying what to do. Then simply point or gesture. When your child is confident with the skill, you can phase out gestures too.

Phase out your help as your child begins to get the idea, but keep saying what to do. Then simply point or gesture. When your child is confident with the skill, you can phase out gestures too.

Tips to help children learn new skills

No matter which of the methods you use, these tips will help your child learn new skills:

- Make sure that your child has the physical ability and developmental maturity to handle the new skill. You might need to teach your child some basic skills before working on more complicated skills.

- Consider timing and environment. Children learn better when they’re alert and focused, so it can be good to work on new skills in the morning or after rest time. It’s also good to avoid distractions, like the TV or younger siblings.

- Give your child the chance to practise the skill. Skills take time to learn, and the more your child practises, the better.

- Give lots of praise and encouragement, especially in the early stages of learning.

Praise your child when they follow your instruction, practise the skill or try hard, and say exactly what your child did well.

Praise your child when they follow your instruction, practise the skill or try hard, and say exactly what your child did well. - Avoid giving negative feedback. Rather than saying your child has done it ‘wrong’, use words and gestures to explain 1-2 things your child could do differently next time.

Remember that behaviour might get worse before it improves, especially if you’re asking more from your child. A positive and constructive approach can help – for example, ‘Well done for getting the knots on your laces right! Would you like to do the loops together today?’

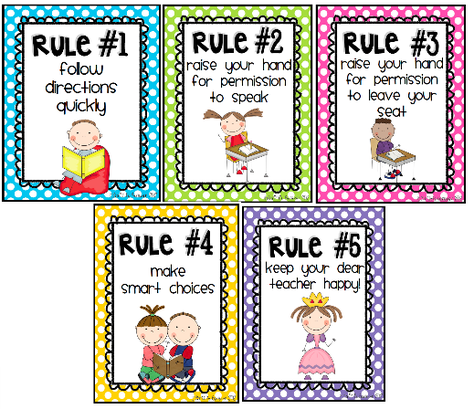

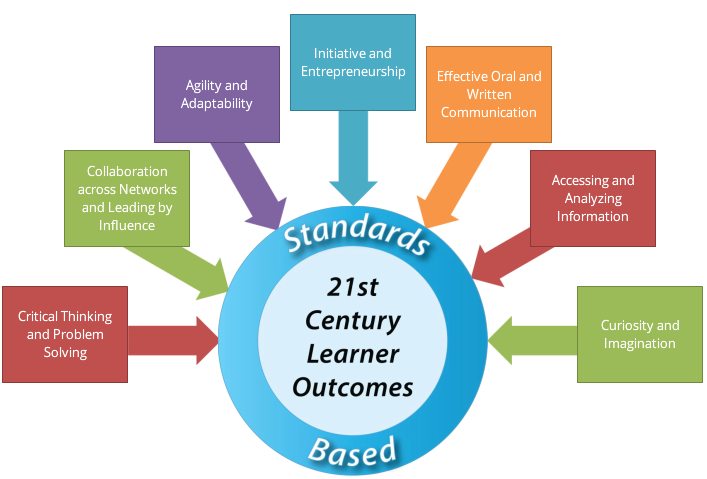

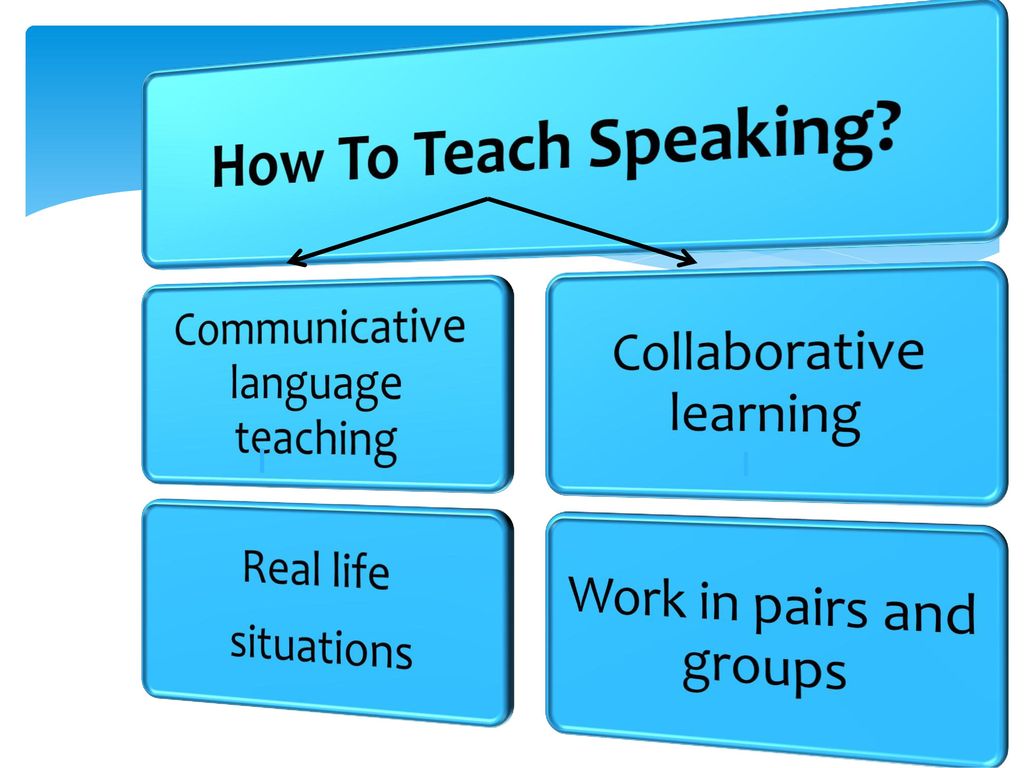

Strategies Teachers Use to Help Kids Who Learn and Think Differently

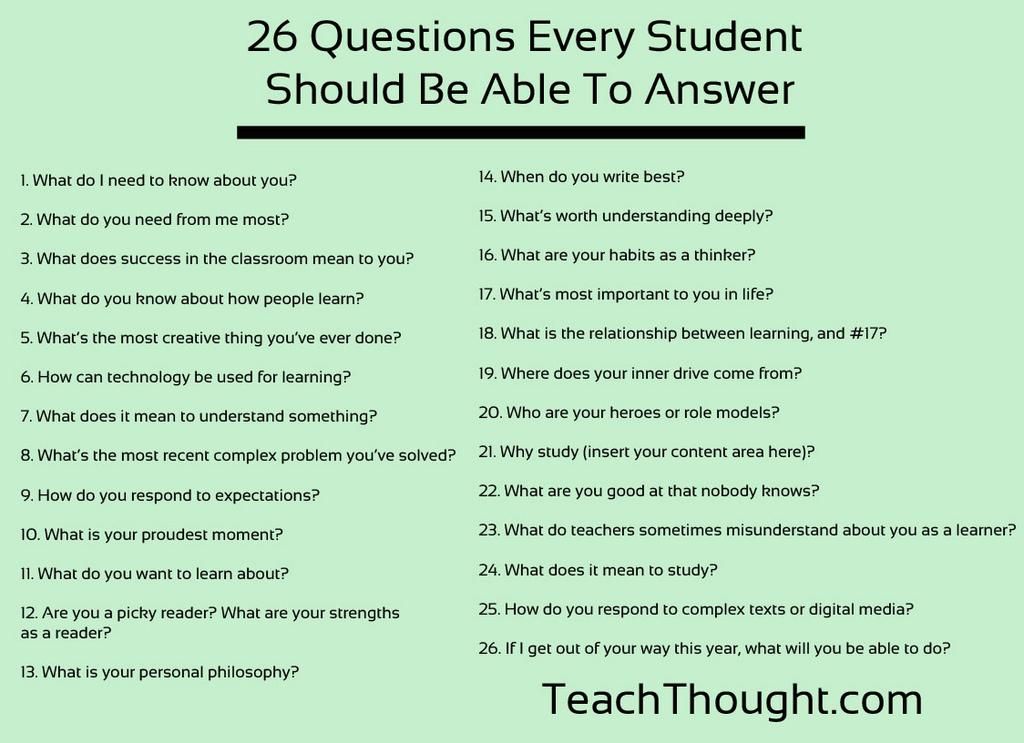

Your child’s teachers may use a variety of teaching strategies in their classrooms. But do these strategies help kids who learn and think differently?

There’s no one way for teachers to deliver instruction to their students. However, some strategies are backed by research and are more effective than others.

These approaches and techniques can benefit all students. But they’re especially helpful to kids who learn and think differently. They can make a big difference in how well struggling students take in and work with information. (Some may even be used as formal accommodations in and .)

But they’re especially helpful to kids who learn and think differently. They can make a big difference in how well struggling students take in and work with information. (Some may even be used as formal accommodations in and .)

You may have heard of one or more of these strategies from your child’s classroom or special education teachers. If not, you can ask the teachers whether they use the strategies and how you might adapt them to use at home.

Here are six common teaching strategies. Learn more about what they are and how they can help kids who learn and think differently.

1. Wait time

“Wait time” (or “think time”) is a three- to seven-second pause after a teacher says something or asks a question. Instead of calling on the first students who raise their hand, the teacher will stop and wait.

This strategy can help with the following issues:

- Slow processing speed: For kids who process slowly, it may feel as though a teacher’s questions come at rapid-fire speed.

“Wait time” allows kids to understand what the teacher asked and to think of a response.

“Wait time” allows kids to understand what the teacher asked and to think of a response. - ADHD: Kids with ADHD can benefit from wait time for the same reason. They have more time to think instead of calling out the first answer that comes to mind.

2. Multisensory instruction

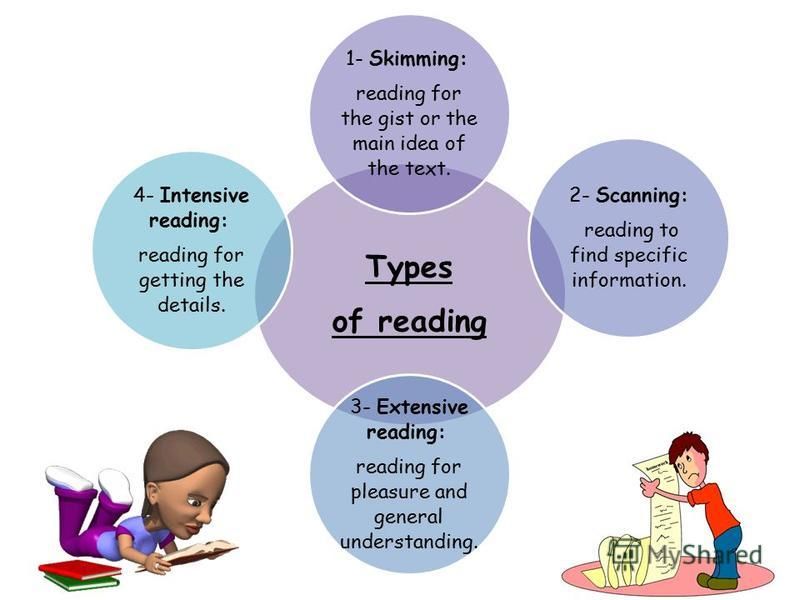

Multisensory instruction is a way of teaching that engages more than one sense at a time. A teacher might help kids learn information using touch, movement, sight and hearing.

This way of teaching can help with these issues:

- Dyslexia: Many programs for struggling readers use multisensory strategies. Teachers might have students use their fingers to tap out each sound in a word, for example. Or students might draw a word in the air using their arm.

- Dyscalculia: Multisensory instruction is helpful in math, too. Teachers often use hands-on tools like blocks and drawings. These tools help kids to “see” math concepts. Adding 2 + 2 is more concrete when you combine four blocks in front of you.

You may hear teachers refer to these tools as manipulatives.

You may hear teachers refer to these tools as manipulatives. - Dysgraphia: Teachers also use multisensory instruction for handwriting struggles. For instance, students use the sense of touch when they write on “bumpy” paper.

- ADHD: Multisensory instruction can help with different ADHD symptoms. That’s especially true if the technique involves movement. Being able to move can help kids burn excess energy. Movement can also help kids focus and retain new information.

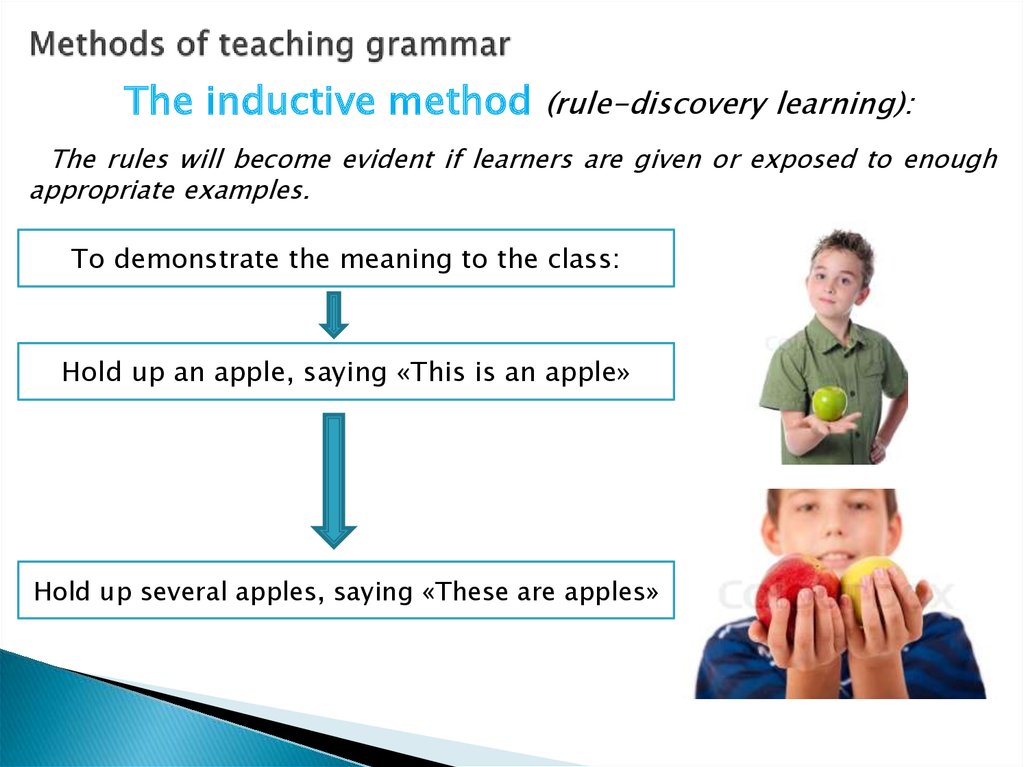

3. Modeling

Most kids don’t learn simply by being told what to do. Teachers use a strategy called “I Do, We Do, You Do” to model a skill. The teacher will show how to do something (“I do”), such as how to do a math problem. Next, the teacher will invite kids to do a problem with the teacher (“we do”). Then, kids will try a math problem on their own (“you do”).

This strategy can help with these issues:

- All learning and thinking differences: When used correctly, I Do, We Do, You Do can benefit all learners.

That’s because a teacher can provide support during each phase. However, teachers must know what support to provide. They also need to know when students understand a concept well enough to work on their own. Think of it like riding a bike: The teacher needs to know when to take off the training wheels.

That’s because a teacher can provide support during each phase. However, teachers must know what support to provide. They also need to know when students understand a concept well enough to work on their own. Think of it like riding a bike: The teacher needs to know when to take off the training wheels.

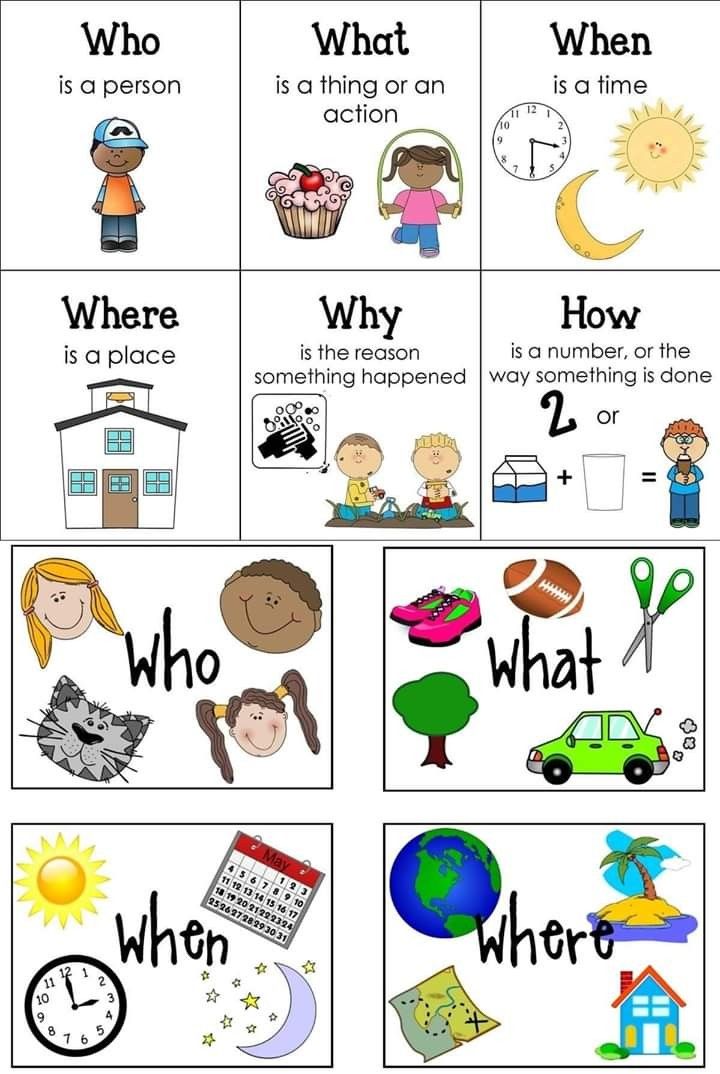

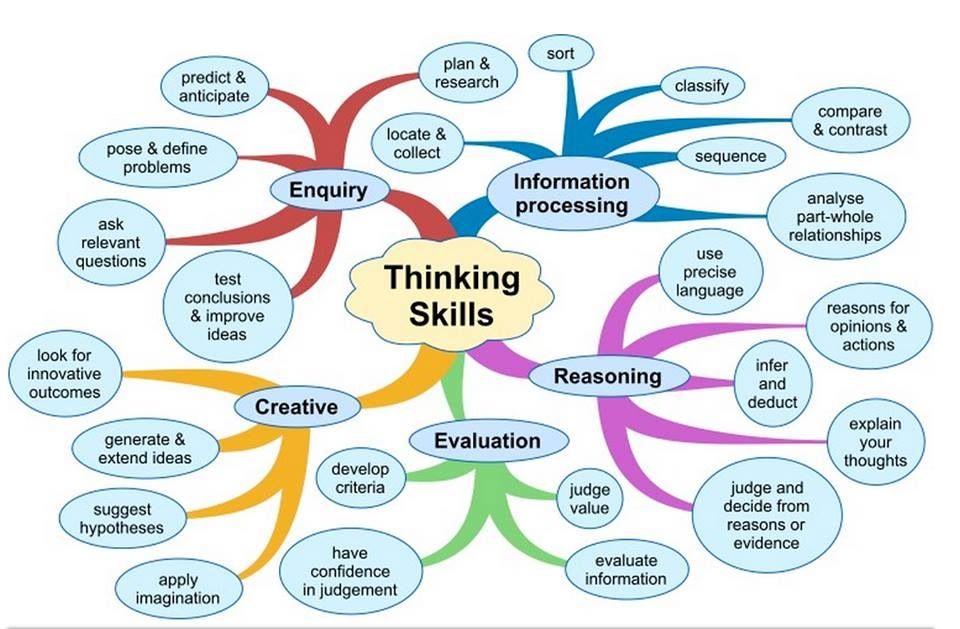

4. Graphic organizers

Graphic organizers are visual tools. They show information or the connection between ideas. They also help kids organize what they’ve learned or what they have to do. Teachers use these tools to “scaffold,” or provide support around, the learning process for struggling learners. (It’s the same idea as when workers put up scaffolding to help construct a building.)

There are many different kinds of graphic organizers, such as Venn diagrams and flow charts. They can be especially helpful with these issues:

- Dyscalculia: In math, graphic organizers can help kids break down math problems into steps. Kids can also use them to learn or review math concepts.

- Dysgraphia: Teachers often use graphic organizers when they teach writing. Graphic organizers help kids plan their ideas and writing. Some also provide write-on lines to help kids space their words.

- Executive functioning issues: Kids with weak executive skills can use these tools to organize information and plan their work. Graphic organizers can help kids condense their thoughts into short statements. This is useful for kids who often struggle to find the most important idea when taking notes.

5. One-on-one and small group instruction

One strategy that teachers use is to vary the size of the group they teach to. Some lessons are taught to the whole class. Others are better for a small group of students or one student. Learning in a small group or one-on-one can be very helpful to kids with learning and thinking differences.

Some kids are placed in small groups because of their IEPs or an intervention. But that’s not always the case. Teachers often meet with small groups or one student as a way to differentiate instruction. This means that they tailor the lesson to the needs of the student.

Teachers often meet with small groups or one student as a way to differentiate instruction. This means that they tailor the lesson to the needs of the student.

This strategy helps with:

- Dyslexia: Students with dyslexia frequently meet in small group settings for reading. In the general classroom, teachers often work with a small group of kids at the same reading level or to focus on a specific skill. They might also meet because kids have a common interest in a book.

- Dyscalculia: For kids with dyscalculia, teachers gather one or more students to practice skills that some students (but not the whole class) need extra help with.

- Dysgraphia: In many classrooms, teachers hold “writing conferences.” They meet with students one-on-one to talk about their progress with what they’re writing. For students with dysgraphia, a teacher can use this opportunity to check in and focus on specific skills for that student.

- ADHD and executive functioning issues: This type of instruction often takes place in settings with fewer distractions.

The teacher can also help students stay on task and learn skills like self-monitoring.

The teacher can also help students stay on task and learn skills like self-monitoring. - Slow processing speed: Teachers can adjust the pace of instruction to give students the time they need to take in and respond to information. In these groups, teachers can focus on the priorities of the lesson so students have the time to grasp the most important concepts. Being in a focused setting may also help decrease the anxiety students feel in whole-class lessons.

6. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) strategies

UDL is a type of teaching that gives all students flexible ways to learn and succeed. UDL strategies allow kids to access materials, engage with them and show what they know in different ways. There are many examples of how these strategies help kids who learn and think differently.

- ADHD: UDL allows students to work in flexible learning environments. For students who struggle with inattention and distractibility, a teacher might allow a student to work in a quiet space away from the class.

Or the student may want to wear earbuds or headphones.

Or the student may want to wear earbuds or headphones. - Executive functioning issues: Following directions can be tough for kids with executive functioning issues. One UDL strategy is to give directions in more than one format. For instance, a teacher might give directions out loud and write them on the board.

- Dyslexia: When teachers follow UDL principles, they present information in many different ways. For instance, instead of telling students they must read a book, they would be invited to listen to an audiobook. This removes a barrier for students who struggle with reading.

- Dysgraphia: One UDL strategy is to give assignment choices. Kids with dysgraphia may struggle to show how much they know about history by writing an essay. But they may shine when delivering a presentation or acting out a historical skit.

To learn more about any of these teaching strategies, talk with your child’s teacher. Ask which strategies they use, whether they are evidence-based and how you might use them at home.

Key takeaways

Some teaching strategies may be part of a child’s IEP or 504 plan.

The strategies aim to give kids needed support as they learn.

Talk with your child’s teachers about the strategies they use.

Related topics

School supports

The 10 most important things parents can teach their children

Source: Le Champ "When your child drives you crazy"

Peter's first day in kindergarten. He's got his hair cut, he's wearing a new red shirt, and he's scared to death. Peter's mother does not understand this because she is sure that Peter is well prepared for kindergarten for his five years. “Well, of course,” she says to the teacher, “he knows the alphabet, counts to a hundred and can write his name.” But, as the teacher soon discovers, Peter was not ready for life in a new environment. He seemed stiff, did not play with other children, and spent much of the day huddled in a corner sucking his thumb. nine0003

nine0003

Michael, who was brought into kindergarten at the same time as Peter, didn't know as much as Peter did. He could hardly count to ten and confused many letters. But, when his mother left, he hopped into the room, smiled shyly at the teacher, walked over to a group of children playing with cars, and asked: "Can I be a mechanic in the garage?" The teacher was delighted with how confident Michael felt and how easily he came into contact with the children, and she thought to herself: "This child is ready to learn to read and write!" nine0003

In the 40 years that I have consistently studied preschoolers, I have become increasingly concerned about parents who think pre-kindergarten preparation is all about memorizing letters or counting. It's not like that at all. I have nothing against learning these essential skills, but I have found that they are best taught and easiest to learn only after a good start has been made in developing other skills.

The 10 most important things parents can teach their children

Too early concentration on theoretical problems can slow down the normal development of the child. We sometimes forget that nature has its own timetable for human development. Trying to teach a three year old to write is like teaching a three month old to walk. You can cause irreversible damage.

We sometimes forget that nature has its own timetable for human development. Trying to teach a three year old to write is like teaching a three month old to walk. You can cause irreversible damage.

If a child goes to kindergarten, feels happy, self-confident, optimistic, inquisitive and friendly, I am sure that he will study well and with pleasure. But, if he is nervous, frightened, irritable and burdened with unfulfilled needs, he will poorly absorb the initial knowledge that will be given to him. In my opinion, a child cannot be considered truly prepared for kindergarten—or for life—until he or she has learned the following ten things. nine0003

1. Love yourself.

Self-love is the most fundamental and essential of all abilities. Until you are able to appreciate your own life, you will never become active, you will not be able to realize your own potentialities. Given how much we love our children, it would be easy for us to convey to them a feeling of love for ourselves, but, apparently, this method is not very reliable.

Try to remember what you thought about yourself when you were five years old. I guess most of us thought we were stupid or ugly. We were angry with ourselves if we were afraid at night, we were ashamed of ourselves if we did not want to share our new doll with our little sister. We were disappointed in ourselves if we were awkward, shy or clumsy, while my mother hoped to raise a ballerina. nine0003

Sometimes we can't help a child love himself until we re-evaluate some of our own attitudes - the burden we carry with us throughout our lives. Perhaps such self-knowledge will be painful, but as a result we will be able to say: “Yes, brown eyes and olive skin really disgust me. My parents created a feeling of inferiority in me, because I looked like their Italian ancestors, and they wanted to be 100% white Americans Now that I have this olive-skinned, brown-eyed baby, can I act like a grown-up and see how beautiful she is and let her know that? nine0003

The irrational prejudices we instill in the cradle are just one of the barriers to helping our children love themselves. Many of us also find it difficult to distinguish "being bad" from "being human". It really makes a difference if, instead of "don't act like a baby," we say, "You're not old enough to be quiet in a restaurant. We'll try to go there again when you're a little older." It's also a completely different thing to say, "You're selfish" or to say, "It's very hard to learn to share with others, but that's okay, I'll help you. If you let Donna play with your bucket, she'll let you play with her truck." nine0003

Many of us also find it difficult to distinguish "being bad" from "being human". It really makes a difference if, instead of "don't act like a baby," we say, "You're not old enough to be quiet in a restaurant. We'll try to go there again when you're a little older." It's also a completely different thing to say, "You're selfish" or to say, "It's very hard to learn to share with others, but that's okay, I'll help you. If you let Donna play with your bucket, she'll let you play with her truck." nine0003

The Puritan assertion that everyone is either good or bad, and that children should therefore be taught to be good, has probably brought more misfortune to mankind than anything else. We are all born as angels and devils in equal measure, and we need to learn how to live with this truth. Sure, we say, "No, you can't hit the kid," but we also say, "You're too small to hold back when you're angry. I have to help you." Learning to admit that you have anger, jealousy, and antisocial impulses is part of growing up. We must also learn to control ourselves, but without denying that such urges exist and without making our children feel like sinners. A child who is told that he behaves badly develops a dislike for himself, and this interferes with learning, life and love more than any other psychological problem. nine0003

We must also learn to control ourselves, but without denying that such urges exist and without making our children feel like sinners. A child who is told that he behaves badly develops a dislike for himself, and this interferes with learning, life and love more than any other psychological problem. nine0003

Once a child feels protected and valued, he begins to develop empathy for others. One of the earliest experiences of this kind occurs with pets. A kid who has experienced tenderness and care is able to carefully hold a homeless kitten in his arms or call his parents for help when someone offends a dog. Any five-year-old child who can spontaneously exclaim at the sight of a bird with a broken wing, "Oh, you poor thing!" has already acquired one of the most fundamental abilities needed to change the quality of all life on this planet. nine0003

2. Interpret behavior.

The child who comes to kindergarten thinking that he is a wonderful creature may nevertheless not get involved in learning if he does not know how to interpret the behavior of others and his own. For example, he might get so caught up in the two girls in the front row who teamed up against him that he can't focus on adding two to five. Or, if the teacher yells at him one morning, he may become so confused and frightened that he will not be able to pay attention in class for the rest of the day. nine0003

For example, he might get so caught up in the two girls in the front row who teamed up against him that he can't focus on adding two to five. Or, if the teacher yells at him one morning, he may become so confused and frightened that he will not be able to pay attention in class for the rest of the day. nine0003

If a child has learned something about the moods of people and their shortcomings, if he has been taught to interpret certain types of behavior, he will not be inclined to be upset in such situations. He will understand that maybe the new kindergarten scares the two girls and they need a common enemy to feel more secure, that his teacher is just in a bad mood: she had a fight with her husband or got into rush hour on her way to work and maybe tomorrow she will ask for forgiveness.

In addition to the fact that the child needs to be able to interpret the behavior of others, he needs to learn how to explain his own behavior. This can have a strong impact on the child's future attitude towards learning activities. If a child yells at his mother at breakfast, if at the sight of an omelette he says: "You know how I hate him, I'm going to throw him in the trash can!" - and then flies out of the house, then one of two things will most likely happen to him today. He may be so overwhelmed with guilt and horror that he will not hear a single word spoken by the teacher. Or he may ask himself what it is that has come over him; consider whether he is still angry with his father for yelling at him last night and decide that he will apologize when he gets home. In the latter case, he is able to forget about the incident while he is in kindergarten. With a mind free from anger and confusion, he well perceives all the explanations of the educator. nine0003

If a child yells at his mother at breakfast, if at the sight of an omelette he says: "You know how I hate him, I'm going to throw him in the trash can!" - and then flies out of the house, then one of two things will most likely happen to him today. He may be so overwhelmed with guilt and horror that he will not hear a single word spoken by the teacher. Or he may ask himself what it is that has come over him; consider whether he is still angry with his father for yelling at him last night and decide that he will apologize when he gets home. In the latter case, he is able to forget about the incident while he is in kindergarten. With a mind free from anger and confusion, he well perceives all the explanations of the educator. nine0003

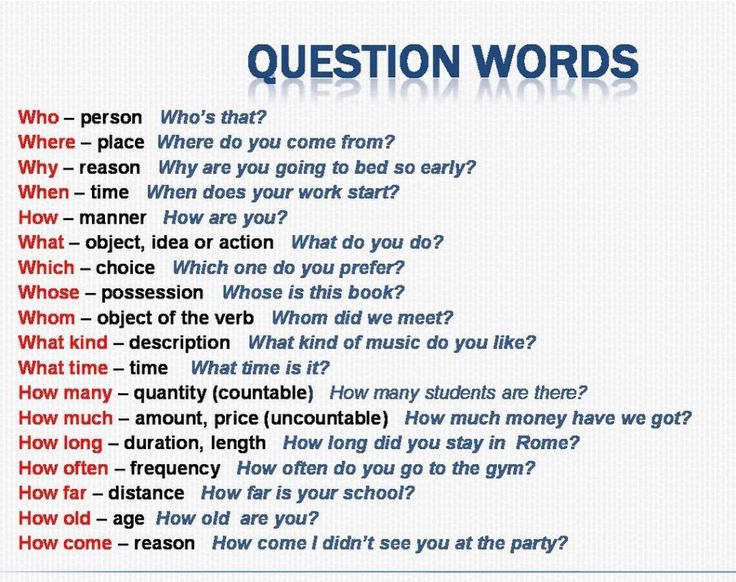

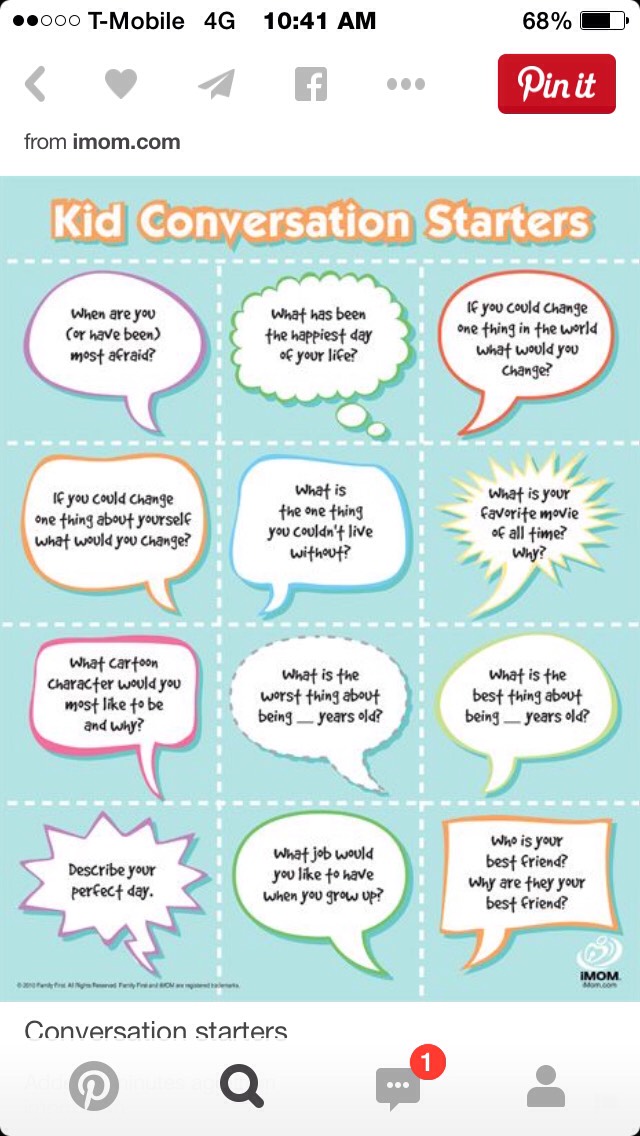

3. Communicate using words.

After children can explain the true meaning of their actions, they need to learn how to help other people understand them. If a girl can tell the teacher, “I was so afraid that I wouldn’t succeed that I just couldn’t think,” the teacher can understand that her fear is interfering with learning and can calm her down properly. If a child can say to his father, "You scare me when you scream so loudly," you can hope that the father will try to negotiate with him calmly instead. Any five-year-old child who can calmly and naturally express his feelings, saying: "I'm afraid" or "I love you very much!" ready to ride a two-wheeled bicycle" has already acquired the ability that will give him the necessary freedom to think, be interested and learn. nine0003

If a child can say to his father, "You scare me when you scream so loudly," you can hope that the father will try to negotiate with him calmly instead. Any five-year-old child who can calmly and naturally express his feelings, saying: "I'm afraid" or "I love you very much!" ready to ride a two-wheeled bicycle" has already acquired the ability that will give him the necessary freedom to think, be interested and learn. nine0003

4. Understand the difference between thoughts and actions.

Without this skill, which is fully developed by the age of five, it will be extremely difficult for a child to concentrate on classes. For example, Gregory looks out the window and imagines himself as a pilot, while the teacher explains the basics of arithmetic to the class. He does not hear what the teacher says at all, because he is very angry. His parents had just divorced, and if his feelings could be brought to the surface, it would most likely be, "I hate them both. I want them to die. " These are such terrible thoughts that Gregory has to concentrate with all his might to keep them out of consciousness. nine0003

" These are such terrible thoughts that Gregory has to concentrate with all his might to keep them out of consciousness. nine0003

If, in the first five or six years of his life, Gregory had been helped to understand that thoughts are not the same as actions, and feelings, properly expressed, do not harm anyone at all, he could give them free rein. And all the energy that was expended in avoiding one's own feelings could be turned to other purposes, including the wonderful powers of addition and subtraction. He certainly needs help to get through this very real crisis, but he should have explained that it is natural to have terrible feelings when you are suffering, when you are anxious, when life is full of torment. It is impossible for a child to concentrate and learn if he has hidden feelings that he himself considers dangerous and bad. nine0003

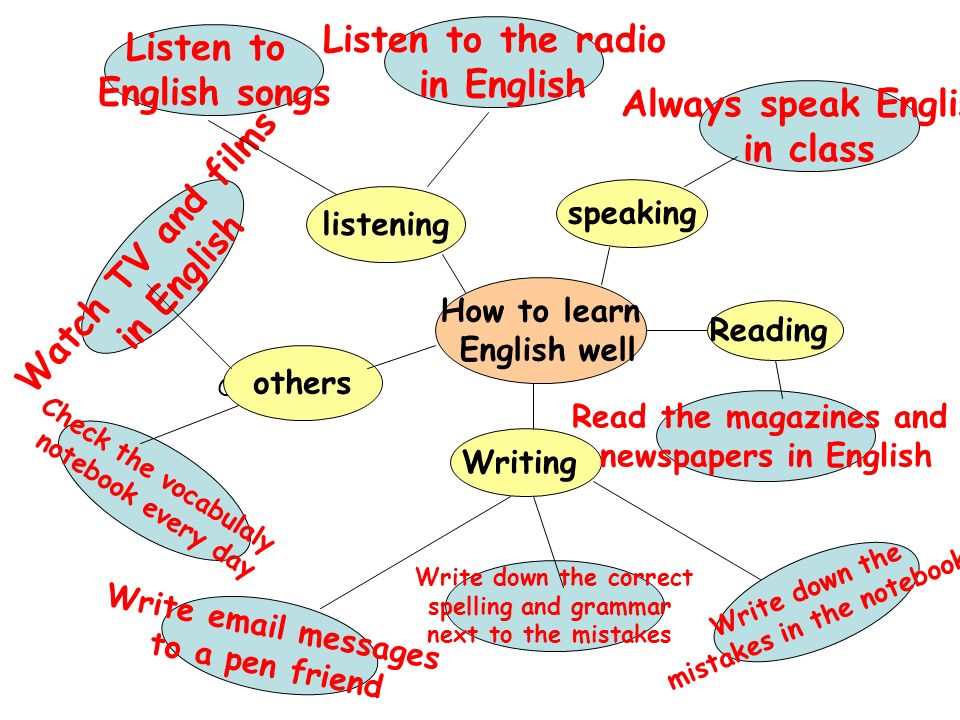

5. Be interested and ask questions.

All the popular books and talk about what kind of activities and skills we should teach preschoolers have relegated to the background and almost nullified natural, instinctive curiosity. We often get so carried away with counting sticks that we stop listening to the wonderful questions that children ask themselves: “Why do leaves change color? .. What makes grass grow? .. Where does snow come from? .. How does an egg make a child?. What does it mean to die?.. Why am I growing up?.. How does milk get to the store?.. Why are some children starving?.. How can a submarine stay under water and not sink?.."

We often get so carried away with counting sticks that we stop listening to the wonderful questions that children ask themselves: “Why do leaves change color? .. What makes grass grow? .. Where does snow come from? .. How does an egg make a child?. What does it mean to die?.. Why am I growing up?.. How does milk get to the store?.. Why are some children starving?.. How can a submarine stay under water and not sink?.."

If we want to maintain this instinct of curiosity, we must make sure that by the time a child is five years old, he revels in his questions and knows that there are ways to find answers to them. He must also learn that some questions have not yet been answered, others have many different answers, and that sometimes he will have to try to find his own.

In her book The Learning Child, Dorothy Cohen, professor of education, makes a crucial distinction between giving a child a fish to eat and teaching a child how to catch a fish. If we give him cooked fish, then we can satisfy his momentary hunger, but what happens if we are not there to feed him? The same thing happens with knowledge and information: if we always present them to a child ready to use, he will never learn to extract them on his own. Children should be taught how they can fish for their own answers. nine0003

Children should be taught how they can fish for their own answers. nine0003

When we say: “I don’t know,” “I’m busy now,” “Ask dad,” or “Don’t talk about this,” we discourage the child from “catching” knowledge himself. If, on the contrary, we encourage his curiosity and help him find answers, we contribute to the development of his intellectual ability, which is most essential for a person.

6. Understand that there are no simple answers to complex questions.

The generation of our children will be forced to face the most serious questions. There can be no simple solutions to such problems as the loss of ecological balance, the population explosion, the proliferation of weapons that can destroy all life. In order to become wise and mature adults, children must begin to understand that simple solutions never solve a problem, that in fact you have to dig deeper to find the most optimal answer to a particular question. nine0003

We need to teach children to look at the root. "Well, maybe Joe is mad today because he came to kindergarten hungry." Or: "If Sarah keeps breaking the clay things you make in kindergarten, we better talk to the teacher. He can talk to Sarah's mom and find out why Sarah is unhappy and what we can do to help her." It's a difficult path, but it gives the child so much more than when we say, "I think Sarah is a bad girl and you better stay away from her." nine0017 There are no easy solutions to social problems, and we will do our children, ourselves, and the future a disservice if we mislead the little ones about this. We put children on the wrong track when we focus on questions that actually have right and wrong answers (how many are three and six? What is the third letter in the alphabet?). Children need to first experience the complexity of life situations so that they are prepared to face the confusion, uncertainty and volatility of real life. nine0003

"Well, maybe Joe is mad today because he came to kindergarten hungry." Or: "If Sarah keeps breaking the clay things you make in kindergarten, we better talk to the teacher. He can talk to Sarah's mom and find out why Sarah is unhappy and what we can do to help her." It's a difficult path, but it gives the child so much more than when we say, "I think Sarah is a bad girl and you better stay away from her." nine0017 There are no easy solutions to social problems, and we will do our children, ourselves, and the future a disservice if we mislead the little ones about this. We put children on the wrong track when we focus on questions that actually have right and wrong answers (how many are three and six? What is the third letter in the alphabet?). Children need to first experience the complexity of life situations so that they are prepared to face the confusion, uncertainty and volatility of real life. nine0003

7. Not being afraid of failure is a necessary condition for growing up.

To learn anything, you must not be afraid to make mistakes, even fail. The first book you turn to may not contain the answer to the question why birds migrate, you will have to look for the answer in some other book. The first wooden table you make may be ugly and lopsided, but if you are able to learn from your mistakes, you will make the next one much better. Children need to be helped to understand that learning is a long, slow process of trial and error. No great invention or scientific discovery has ever been made without a large number of trials and failures that preceded it. nine0003

We must make it very clear to them that success and failure is not what learning is all about. To quote a wise primary school teacher: “Schools should really teach kids to be players! The only way to find out what you know and what you don’t know is to take a little risk. learn something new if success or failure is evaluated instead of trying? nine0003

8. Trust adults.

A five-year-old child needs to have true trust in adults if he is to focus all his attention on learning tasks. And it’s hard to trust people if they deceive you, they say that they won’t go anywhere, but when you wake up, you find a nanny in the place of your parents; they say the doctor won't hurt you, but he does. We pay a very high price for the games we play with our children to keep them from crying. If you want to be believed, it's better to say, "I'm going to go out for a few hours while you sleep," even if you have to endure a painful goodbye. And the doctor: "You may be in a little pain, but it will pass soon. You can sit on my lap and cry if you want." nine0003

Many adults think they can build trust if they are consistent, but I think this is a big mistake. There is a very thin line between consistency and rigidity, and I believe that it is important to trust people, even if their feelings and intentions change. People change with age, and we are all subject to mood swings. Consistency in one thing is important for a child: in our attempts to be honest with him, explaining as best as possible where we are inconsistent, and apologizing if this inconsistency is not justified. nine0003

Consistency in one thing is important for a child: in our attempts to be honest with him, explaining as best as possible where we are inconsistent, and apologizing if this inconsistency is not justified. nine0003

It is quite possible to help a child understand that not all people are kind, and at the same time create in him the feeling that most contacts with adults will be good. Cultivating confidence in this partly depends on how willing we are to share the child's feelings about people. We have to be frank with children, sometimes saying, "Yes, you're right, your teacher really makes too much noise about washing hands" or "Yes, I understand what you mean about aunt, she likes to command too much when we are coming". nine0003

Distrust arises from the feeling that only you see unpleasant qualities in other people, and for children this feeling is not uncommon. We will not break a child's trust if we acknowledge human imperfection.

9. Think for yourself.

To say "no" is really to say "I exist". This begins as the child has some idea of himself, a feeling that he is in fact an independent person. Many parents are frightened and angered by this possibility, when they should be glad about it. A sense of one's own uniqueness and ability to choose is a vital part of human existence. nine0003

This begins as the child has some idea of himself, a feeling that he is in fact an independent person. Many parents are frightened and angered by this possibility, when they should be glad about it. A sense of one's own uniqueness and ability to choose is a vital part of human existence. nine0003

If a child has some idea of who he is, he will inevitably have his own opinion by the age of five. This ability is very easy to teach - you just need to encourage the child to express his judgment without fear of being punished. None of us wants to raise a person who is weak in spirit or intellectually weak, we want our children to make serious decisions, have common sense and inner convictions. And we can't wait for a child to go to college to develop these abilities. nine0003

These principles are already at work when we say, "Now that you're almost three years old, I think you can decide whether we buy you a blue jumpsuit or a red one." Or, "While we're eating cornflakes for breakfast, you can make yourself a butter and jam sandwich. " Or: "Well, our neighbor does not annoy me, but you have the right to your own opinion."

" Or: "Well, our neighbor does not annoy me, but you have the right to your own opinion."

When we demonstrate respect for the child's personality, for his emerging views, likes and dislikes, we prepare him for situations in which he will have to make a decision on his own, for example, whether or not to join a group of children who decide to explore a destroyed house, or whether or not to go with a stranger who said he knew his father. When we lose our temper over "no" at two and a half years old, we should keep in mind that there will come a time when we will be grateful that our child is able to say "no". Judgment is corrected by practice. nine0003

10. Know what you can rely on an adult.

By the time a child is five years old, in my opinion, he should know that there are many situations that he simply cannot control. He cannot cope with the company of older children, with teenagers who impose drugs, with the wild behavior of the class in the lessons of an inexperienced teacher. Part of trusting adults is knowing when you need help and being able to ask for it. It may seem simple, but surprisingly few children come into kindergarten or classroom able to do it. As a result, many of them quickly find themselves in situations that frighten and overwhelm them so much that learning becomes impossible. We need to explain to children that we can be friends, help them, without treating them like small children, without excessive guardianship, we can understand their world. We say that we attach great importance to the rights of the small and weak, but often do not include our children in these idealistic constructions. nine0017 Learning is much easier if the child does not have unsatisfied needs in early childhood. If we pay more attention to deep human values, we can raise a generation of wise and loving people who will be able to change and can make the world a better place.

Part of trusting adults is knowing when you need help and being able to ask for it. It may seem simple, but surprisingly few children come into kindergarten or classroom able to do it. As a result, many of them quickly find themselves in situations that frighten and overwhelm them so much that learning becomes impossible. We need to explain to children that we can be friends, help them, without treating them like small children, without excessive guardianship, we can understand their world. We say that we attach great importance to the rights of the small and weak, but often do not include our children in these idealistic constructions. nine0017 Learning is much easier if the child does not have unsatisfied needs in early childhood. If we pay more attention to deep human values, we can raise a generation of wise and loving people who will be able to change and can make the world a better place.

The material was prepared by the head of the MDOU d / s No. 38 S.I. Taganova

8 simple steps, how to teach children to respect and hear their parents?

Naughty children: why did they not please their parents? nine0017 For such children to behave "normally", adults have to make efforts: restrain, control, repeat, refuse, punish and warn. And that's the point: we don't want to strain ourselves by raising children. It would be more convenient for the child to be controlled like a toy with a remote control.

And that's the point: we don't want to strain ourselves by raising children. It would be more convenient for the child to be controlled like a toy with a remote control.

You tell your child: “You need to wash your face” or “Wash your hands!”, but he does not listen to you. You remind that it's time to break away from the computer and sit down for lessons, he frowns with displeasure: "Leave me alone!" - Of course, it's a mess. nine0003

Smart parents have funny, smart and obedient children. Moreover, smart and loving parents take care of this: they make sure that their children are not only smart, but also obedient. This seems obvious: if you want to teach a child to do good things, you first need to teach him to obey you elementarily.

Unfortunately, ordinary children have long been accustomed to not listening to their parents: you never know what they say! And the point here is not in the children, but in us, in the parents, when we say things that are important for us to the children somehow not seriously, not paying attention to whether the children are listening to us or not, when we put forward our demands unconvincingly. nine0003

nine0003

Your requests should be calm but clear instructions, sound weighty and be accompanied by control. The child must know that your words are not empty words, and if you warn that toys that are not removed are thrown away, they really disappear. If a parent approaches a child with a confident request, knowing that he has leverage, the child will respond to such a request.

But it's not just about the right wording and levers of influence, there is another important trick in building relationships with a child, namely, whether your child has a HABIT to obey you. "To obey or not to obey parents" is determined not only by what and how the parents say, it is also determined simply by the child's habits. nine0003

There are children who have the habit of mindlessly obeying everyone, and there are children who have the same habit of mindlessly disobeying anyone. Obeying "everyone" or "no one" are equally bad habits, but the habit of obeying selectively, namely, OBEYING YOUR PARENTS, is a great habit! Your children should have the habit of paying attention to what you say, the habit of doing what you ask them to. Teach your child to listen and obey you, and you will have your parental authority, you will have the opportunity to raise a developed and thinking person from your child. nine0003

Teach your child to listen and obey you, and you will have your parental authority, you will have the opportunity to raise a developed and thinking person from your child. nine0003

Is it difficult to get your children into this habit? Much depends on age: it is difficult to teach a teenager to obey his parents, it is almost impossible for many mothers, and developing such a habit in a small child is a solvable task. In principle, the sooner you begin to develop in your child the habit of listening and obeying you, the easier it will be for you.

The easiest method to help you with this is the "Eight Steps" method. Its idea is to teach your child to obey you, starting with the simplest, most elementary things, and very gradually, methodically move step by step to more difficult things. From simple to complex. nine0003

First, we do what any parent can do with any child, then we add a little, then a little more - and so we go a long way from a natural child to a well-bred child who already understands that people who are loving and more experienced than him should obey right.

The age at which the Eight Steps algorithm works best is from 2 to 12 years. After 12 years, a well-bred child should already become your friend and helper, you are no longer so much raising him, but helping him in his self-education, helping him to solve life's tasks in the best way. nine0003

Now let's get down to business. What are these steps?

Step 1: Addition.

As the King from Antoine Saint-Exupéry's fairy tale "The Little Prince" said, controlling the sunrise is easy, you just need to know when the sunrise occurs. Say at the right moment: "Sun, rise!", and you will become the lord of the rising sun... So is the child: if the child does not obey you yet, he still does something. Go from what is, adapt to what he does, and direct his activity in the direction you need. nine0003

The child runs, you shout to him: "Well done, faster, faster!" - he happily adds speed.

Sit down at the table, you know what the child likes, what he will still reach for. Get ahead of him: "Take your favorite bread!" You said he took it.

Get ahead of him: "Take your favorite bread!" You said he took it.

Little Nikita likes to clap his hands. "How does Nikita clap her hands? - Clever girl, Nikita! And now, Nikita, show me how the car hums! ... Wonderful!" - you teach him to do what you tell him. He is one and a half years old, and he is already learning to listen to you and obey. nine0003

If you can't manage, take the lead. You cannot (yet) control the behavior of the child - adapt to what he does anyway, and what he wants to do himself.

Step 2: Taming: Train to come when called.

Do you know what "attach" means? The fisherman throws food into the river - he attracts fish. When an ancient man decided to tame wild dogs, he also started with affection, then he began to feed them, then stroke them, and gradually taught them to run up to him when he called them. Have you already tamed your children? Do they come running to you when you call them? If your children are still wild, start like an ancient man by taming them. nine0003

nine0003

Your child likes to crunch apples or nibble cookies: your task is to make sure that access to these sweets is not free, but only through you. This is not in the vase, but you can give it to your child. Now you don’t wait until he starts begging from you, but choosing a good time, you yourself announce: “Who wants a tasty apple, quickly runs to me!”, “Cookies, cookies, delicious cookies for obedient kids.” Children run, you treat them and pat them on the head: "Well done, how quickly you run to your mother!" So the hunt has taken place - you are already accustoming children to come to you when you call them. nine0003

Invite your child to you - and praise him when he comes to you! A bait can be not only food, but everything that the child likes: and squeeze the cream on the cake, and cut the bread, and the time when you can play with the child in the games that he loves. "Mom has five minutes! Whoever comes running quickly can play hide and seek with her!" Important: if a child comes running, you reinforce it: give a bait and praise. If the child is in no hurry to run, comes later and demands, you don’t give a bait: “That’s it! It’s all over!”, but you prompt: “When mom calls, you need to run quickly!”. Teach your child to fulfill your requests, reinforcing it with joy. nine0003

If the child is in no hurry to run, comes later and demands, you don’t give a bait: “That’s it! It’s all over!”, but you prompt: “When mom calls, you need to run quickly!”. Teach your child to fulfill your requests, reinforcing it with joy. nine0003

Step 3. Learning to negotiate.

Your child will be intelligent and not capricious if you teach him to use his mind. And for this, take the time to explain to the child what is good and what is bad - and teach him to negotiate. You can try to talk intelligently with a child even at two years old, and if your child is already three years old, this is already a must. Teach your child to negotiate and fulfill agreements!

You and your child are on the playground, it's time for you to leave, but the child doesn't want to leave, he wants to play more. Just command? nine0003

The child may begin to protest with a roar. What to do?

Negotiate.

The first agreement - before coming to the playground. "You want to go to the playground, but we can't play there for a long time, I will need to return home, cook dinner. You promise me that when I say that it's time for us, you won't cry, but will say goodbye to all the children and go with me home? Won't you keep me?" The second conversation is when it's time for you to leave. Most likely, the child will begin to whine: "Mom, I have a little more!". Here your task is to calmly cut him off from the players and discuss how to behave correctly in such a situation. “If you promised that you would not whine and cry when you need to go home, you can’t whine and cry. Otherwise, how will they believe you next time?” nine0003

You promise me that when I say that it's time for us, you won't cry, but will say goodbye to all the children and go with me home? Won't you keep me?" The second conversation is when it's time for you to leave. Most likely, the child will begin to whine: "Mom, I have a little more!". Here your task is to calmly cut him off from the players and discuss how to behave correctly in such a situation. “If you promised that you would not whine and cry when you need to go home, you can’t whine and cry. Otherwise, how will they believe you next time?” nine0003

Here it is important that respect for agreements is supported by all close adults, there is only one position: "Agreed - it is necessary to fulfill it. And whoever does not fulfill the agreements is a violator, a whim and a small one, nothing serious can be allowed to him." We agree and do not be capricious.

Step 4: No whims.

An obedient child not only DOes what you ask him to do, he also STOPS doing what you do not like. The child tries to fight the will of his parents through his whims and tantrums, and your task at this step is to stop reacting to them in any way. Learn to do your own thing without reacting to the whims of the child - in those cases when you yourself are sure that you are right and you know that everyone will support you. nine0003

The child tries to fight the will of his parents through his whims and tantrums, and your task at this step is to stop reacting to them in any way. Learn to do your own thing without reacting to the whims of the child - in those cases when you yourself are sure that you are right and you know that everyone will support you. nine0003

You are all hurrying to the train, packing your things. In this case, the whims of the child "Come play with me!" will be easily ignored by everyone, including grandmothers. Teach your child that there are important things to do. Teach your child to say, "This is important." If you sat down in front of him and, looking into his eyes, holding his shoulders, calmly and firmly say: "Adults now need to get together, and we will play with you later. This is important!" - then soon the child will begin to understand you. It is important!

Step 5: Requirements. nine0003

Your child already quickly comes running to you when you call him with something tasty, has stopped being capricious and no longer throws tantrums. As a rule, he will do what you asked him to do, but he is not yet used to the fact that you can seriously demand something from him. Requests are soft, while demands are hard and mandatory. Is that the way to listen? At this step, again act consistently, but carefully, at first demand a minimum and only when everyone supports you.

As a rule, he will do what you asked him to do, but he is not yet used to the fact that you can seriously demand something from him. Requests are soft, while demands are hard and mandatory. Is that the way to listen? At this step, again act consistently, but carefully, at first demand a minimum and only when everyone supports you.

The child is already old enough to... In order not to take away a toy from someone else's child, to pick up a fallen mitten yourself, to put porridge in your mouth yourself... - Always look for those moments when your demands will be supported by everyone around you, so that even the grandmothers at least kept silent. nine0003

If you have too many demands on your child, if he does not keep up with your numerous demands, or if you do not have the support of others, do not push. Like politics, education is the art of the possible. Napoleon himself taught his commanders: "Give only those orders that will be carried out."

Nevertheless, gradually remove the bait as something obligatory, start calling the child already without rewarding him with something tasty. It's time to teach the child that if mom (especially dad) is his name, you need to come simply because he was called. If he doesn’t go right away, they repeated it, but achieved it. And now they drew his attention to the fact that you had to wait for him, and asked him to come when his mother calls. No need to swear, just say: "When mom calls, you need to come right away!" - and kiss! Slowly, your child will begin to learn it. nine0003

It's time to teach the child that if mom (especially dad) is his name, you need to come simply because he was called. If he doesn’t go right away, they repeated it, but achieved it. And now they drew his attention to the fact that you had to wait for him, and asked him to come when his mother calls. No need to swear, just say: "When mom calls, you need to come right away!" - and kiss! Slowly, your child will begin to learn it. nine0003

Step 6: Responsibilities.

Requirements are one-time, while duties are a system of permanent requirements for a child. The time has come to teach the child that each member of the family has his own responsibilities, and he must participate in family affairs on an equal basis with mom and dad. Having explained this to the child, begin to confidently give him tasks, but also act gradually here: let him first choose his duties according to his strength, let him do what is not difficult for him, or, all the more, even want a little.

This step is more difficult for mothers than for children. Moms really want to do everything themselves and not strain the child. So, dear mothers and, in principle, parents, make sure that the child always has things to do at your request. The child should not fade away the understanding that he has tasks, and he must do it. Clean up the bed, take away the cup, wash the dishes, run to the store - most likely, it’s easier and cheaper for you to do it all yourself, but you are educators, so your task is to restrain yourself, not to do it yourself and entrust it to the child every time . nine0003

Moms really want to do everything themselves and not strain the child. So, dear mothers and, in principle, parents, make sure that the child always has things to do at your request. The child should not fade away the understanding that he has tasks, and he must do it. Clean up the bed, take away the cup, wash the dishes, run to the store - most likely, it’s easier and cheaper for you to do it all yourself, but you are educators, so your task is to restrain yourself, not to do it yourself and entrust it to the child every time . nine0003

At first, the child has to be reminded of his duties, after a while the duty to remember should fall on the child himself. Remembering your responsibilities is also the responsibility of the child!

Step 7: Self-reliance.

When a child already knows what duties are, it's time to teach him to be independent. The ability to obey is the basis of smart independence. The independence of an obedient child lies in the fact that you can already give him difficult tasks in the confidence that he will complete them completely on his own, without your help and prompts. It’s not just “Go to the store” or “It’s your responsibility to take out the bucket”, but “Pack up all the things you will need on the trip”, “Grandma needs help digging up a garden in the country”, “Toothache? Call the clinic, Find out when the doctor is, go and get your teeth fixed." As usual, not everything will turn out right away, at first the child will need your tips, help and support, but the more often he begins to successfully cope with difficult assignments, the faster he will wake up a taste for independence. So, move from simple to complex, from dense, frequent and specific clues to rare and general clues, and thus gradually move on to more and more difficult and independent tasks, mostly on the most positive background, with small irregular reinforcements and rare large ones. nine0003

It’s not just “Go to the store” or “It’s your responsibility to take out the bucket”, but “Pack up all the things you will need on the trip”, “Grandma needs help digging up a garden in the country”, “Toothache? Call the clinic, Find out when the doctor is, go and get your teeth fixed." As usual, not everything will turn out right away, at first the child will need your tips, help and support, but the more often he begins to successfully cope with difficult assignments, the faster he will wake up a taste for independence. So, move from simple to complex, from dense, frequent and specific clues to rare and general clues, and thus gradually move on to more and more difficult and independent tasks, mostly on the most positive background, with small irregular reinforcements and rare large ones. nine0003

Ideally, if you go somewhere for a relatively long time, your child should be able to live without you without major problems. He is already on his own!

Step 8: Responsibility.

Well, the last step remains: responsibility. Women do not really like the word "responsibility", they are closer to "caring", but there is a difference between these words: a caring person pays only with efforts and soul, and a person responsible for his mistakes pays really. If you entrust a child with a responsible task, for this, in the event of a puncture, either the child or you will have to pay. But children grow up, it's time to acquaint them with responsibility, and now you entrust the child with not just deeds, but responsible deeds: those for which you need to answer to other people or, simply, pay for mistakes. nine0003

Women do not really like the word "responsibility", they are closer to "caring", but there is a difference between these words: a caring person pays only with efforts and soul, and a person responsible for his mistakes pays really. If you entrust a child with a responsible task, for this, in the event of a puncture, either the child or you will have to pay. But children grow up, it's time to acquaint them with responsibility, and now you entrust the child with not just deeds, but responsible deeds: those for which you need to answer to other people or, simply, pay for mistakes. nine0003

You instructed a child to place an expensive service on the table. Or put money in the bank. Or - to bring a little sister from the kindergarten ... Will she not break it? Will not lose? Will not forget?

When taking on a responsible task, the child already knows the price of a mistake, and treats the assignment responsibly: he will think everything over, remember, follow up and check, and will definitely report back to you at the end.

When a child learns this too, you can be proud - you are already an adult. You have raised an adult, responsible person! Remember, it all started with quiet, neat outbuildings to a completely naughty child? nine0003

Of course, and after that no one will promise you that your children will become angels and will never disobey you. Everything is possible, our children do not always obey us. Sometimes it happens by accident, sometimes on purpose. How to react to it? Calmly. If you act wisely, you will solve this issue without difficulty.

By the way, is there anything after the eighth step, after the formation of responsibility in the child? Your child is not only ready to fulfill your requests, he knows his duties, he is a completely independent and responsible person. And it's all? Is there anything else we want to give our child? Tell me, when and how will we set the task so that our children grow up as loving people? nine0003

Should children listen unquestioningly to their parents?

There can be no unambiguous answer to this question precisely because parents are different.