Domestic violence on a pregnant woman

Abuse during pregnancy

Topics

In This Topic

Abuse, whether emotional or physical, is never okay. Unfortunately, some women experience abuse from a partner. Abuse crosses all racial, ethnic and economic lines. Abuse often gets worse during pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (also called ACOG) says that 1 in 6 abused women is first abused during pregnancy. More than 320,000 women are abused by their partners during pregnancy each year.

What is abuse?

Abuse can come in many forms. An abusive partner may cause emotional pain by calling you names or constantly blaming you for something you haven't done. An abuser may try to control your behavior by not allowing you to see your family and friends, or by always telling you what you should be doing. Emotional abuse may lead you to feel scared or depressed, eat unhealthy foods, or pick up bad habits such as smoking or drinking.

An abusive partner may try to hurt your body. This physical abuse can include hitting, slapping, kicking, choking, pushing or even pulling your hair. Sometimes, an abuser will aim these blows at a pregnant woman's belly. This kind of violence not only can harm you, but it also can put your unborn baby in grave danger. During pregnancy, physical abuse can lead to miscarriage and vaginal bleeding. It can cause your baby to be born too soon, have low birthweight or physical injuries.

What can trigger abuse during pregnancy?

For many families, pregnancy can bring about feelings of stress, which is normal. But it's not okay for your partner to react violently to stress. Some partners become abusive during pregnancy because they feel:

- Upset because this was an unplanned pregnancy

- Stressed at the thought of financially supporting a first baby or another baby

- Jealous that your attention may shift from your partner to your new baby, or to a new relationship

How do you know if you’re in an abusive relationship?

It's common for couples to argue now and then. But violence and emotional abuse are different from the minor conflicts that couples have.

But violence and emotional abuse are different from the minor conflicts that couples have.

Ask yourself:

- Does my partner always put me down and make me feel bad about myself?

- Has my partner caused harm or pain to my body?

- Does my partner threaten me, the baby, my other children or himself?

- Does my partner blame me for his actions? Does he tell me it's my own fault he hit me?

- Is my partner becoming more violent as time goes on?

- Has my partner promised never to hurt me again, but still does?

If you answered "Yes" to any of these questions, you may be in an unhealthy relationship.

What can you do?

Recognize that you are in an abusive relationship. Once you realize this, you've made the first step towards help. There are lots of things you can do.

Tell someone you trust. This can be a friend, a clergy member, a health care provider or counselor. Once you've confided in them, they might be able to put you in touch with a crisis hotline, domestic violence program, legal-aid service, or a shelter or safe haven for abused women.

Have a plan for your safety. This can include:

- Learn the phone number of your local police department and health care provider's office in case your partner hurts you. Call 911 if you need immediate medical attention. Be sure to obtain a copy of the police or medical record should you choose to file charges against the abuser.

- Find a safe place. Talk to a trusted friend, neighbor or family member that you can stay with, no matter what time of day or night, to ensure your safety.

- Put together some extra cash and any important documents or items you might need, such as a driver's license, health insurance cards, a checkbook, bank account information, Social Security cards and prescription medications. Have these items in one safe place so you can take them with you quickly.

- Pack a suitcase with toiletries, an extra change of clothes for you and your children, and an extra set of house and car keys.

Give the suitcase to someone you trust who can hold it for you safely.

Give the suitcase to someone you trust who can hold it for you safely.

Remember: No one deserves to be physically or emotionally abused. Recognize the signs of abuse and seek help. You might feel very scared at the thought of leaving, but you've got to do it. You and your baby's life depends on it.

More information

- National domestic violence hotline: (800) 799-SAFE (7233) or (800) 787-3224 TTY

') document.write('

Nutrition, weight & fitness

') document.write('') }

') document.write('') }

With homicide a leading cause of maternal death. doctors urged to screen pregnant women for domestic violence

Giving birth in the US is more dangerous than you think

01:37 - Source: CNN

CNN —

Two researchers are urging health-care providers to educate and screen pregnant women about intimate partner violence, as women in the United States are more likely to be murdered during pregnancy or postpartum than to die of common obstetric causes such as high blood pressure, hemorrhage or sepsis.

Other research suggests that they are also at higher risk of homicide than women who are not pregnant.

Pregnancy-related homicides are often linked to domestic violence and firearms – but they are preventable, Rebecca Lawn and Karestan Koenen of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health wrote in an editorial published Wednesday in the medical journal BMJ.

H. Chan School of Public Health wrote in an editorial published Wednesday in the medical journal BMJ.

Shutterstock

US sees continued rise in maternal deaths -- and ongoing inequities, CDC report shows

“Women are likely to have multiple visits with healthcare professionals during pregnancy, providing opportunities to identify and help women at risk of violence and potentially prevent pregnancy-associated homicides,” Lawn wrote in an email to CNN on Thursday. “However, recent legislation in the US to restrict women’s access to reproductive care and abortion reduces these potential opportunities to help and could place women at further risk of violence.”

She also cited legislation around firearms as affecting women’s risks of intimate partner violence.

“While many factors contribute to the high maternal mortality rates observed in the US, the inextricable and lethal link between intimate partner violence and gun violence must be considered. Pregnancy represents a particularly high-risk time for experiencing intimate partner violence and women are more likely to be killed by an intimate partner if their partner has access to a firearm,” Lawn said. “Firearm legislation is more lenient in the US and rates of both intimate partner violence and gun ownership are higher than in other high-income countries – this backdrop likely contributes to the high rates of pregnancy-associated homicide we observe in the US.”

Lu Libing's wife, Mu, poses for pictures during an interview with Reuters at their home in Ganzhou, Jiangxi province March 13, 2014. Lu knew he had only one choice as the birth of his third child approached. He couldn't afford hefty fines that would be meted out by Chinese authorities, so he put the unborn child up for adoption. On the Internet he found "A Home Where Dreams Come True", a website touted as China's biggest online adoption forum, part of an industry that has been largely unregulated for years. Demand for such websites has been fuelled by rural poverty, China's one-child policy, limiting most couples of only one child, and desperate, childless couples. To match story CHINA-ADOPTIONS/ Picture taken March 13. REUTERS/Alex Lee (CHINA - Tags: SOCIETY POVERTY)

Lu knew he had only one choice as the birth of his third child approached. He couldn't afford hefty fines that would be meted out by Chinese authorities, so he put the unborn child up for adoption. On the Internet he found "A Home Where Dreams Come True", a website touted as China's biggest online adoption forum, part of an industry that has been largely unregulated for years. Demand for such websites has been fuelled by rural poverty, China's one-child policy, limiting most couples of only one child, and desperate, childless couples. To match story CHINA-ADOPTIONS/ Picture taken March 13. REUTERS/Alex Lee (CHINA - Tags: SOCIETY POVERTY)

The US has the highest maternal death rate of any developed nation. California is trying to do something about that

Most people tend to think of clinical causes of maternal death – such as preeclampsia or gestational diabetes – but Lawn and Koenen’s editorial provides insights into intimate partner violence as another cause, said Dr. Zenobia Brown, senior vice president of population health and associate chief medical officer at Northwell Health, a health-care network in New York.

Zenobia Brown, senior vice president of population health and associate chief medical officer at Northwell Health, a health-care network in New York.

“I applaud the article because I think it surfaces things that we otherwise don’t want to look at because they’re very difficult and because traditionally, health care hasn’t really dealt with those issues well,” she said.

Brown added that intimate partner violence has been part of discussions around maternal health at Northwell’s Center for Maternal Health, as well as assessing women for risks of intimate partner violence.

Ian Waldie/Getty Images AsiaPac/Getty Images

4 out of 5 pregnancy-related deaths in the US are preventable, CDC finds

“There is a very heavy focus in general on assessment, asking the right questions and listening, and in particular, assessing for these things that traditionally we have not assessed for, like intimate partner violence, like history of trauma, behavioral health,” Brown said.

“We tend to think about maternal mortality, or maternal issues, as a point in time or a moment in time for women and I think what people need to understand more and more is that it is about the entire lifecycle of a woman, of her family, of everyone who touches that familial unit,” she said. “We should not be waiting for a woman to be pregnant to be asking these questions. ”

”

A study published in August in the American Journal of Public Health found that pregnancy-associated homicides in the United States have risen substantially in recent years, and the risk of homicide was 35% higher for pregnant and postpartum women than for their counterparts who are not pregnant nor postpartum.

Data on maternal deaths related to intimate partner violence is often lacking – but screening can help, said Kamila Alexander, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing.

She also said that Black women are at higher risk of maternal deaths due to homicide than white women and that monitoring those racial disparities is important.

“There’s not consistent screening in the clinical setting. So documented violence occurring during the time of pregnancy is likely inconsistent – so linking it to a death can be challenging,” Alexander said. “There’s a lot of holes in the data that we have.”

Domestic violence against pregnant mothers was linked to the deterioration of the intelligence of their children

British scientists found that domestic violence against a pregnant woman is associated with a deterioration in the mental abilities of her child. Children whose mothers were abused had an IQ that was 3 to 5 percent below normal. At the same time, indicators suffered more from physical abuse of the mother than from psychological abuse, scientists write in the journal Wellcome Open Research .

Partner violence is still widespread even in developed countries. At least as far back as 2013, the WHO reported that 23 percent of women in high-income countries experienced violence. If a woman is pregnant, then not only she herself suffers, but also her child. It is known, for example, that stress during pregnancy can lead to a variety of consequences for the fetus - from preterm birth to neurological abnormalities. However, there is little research on how violence against a mother during pregnancy is related to the cognitive abilities of her child.

At least as far back as 2013, the WHO reported that 23 percent of women in high-income countries experienced violence. If a woman is pregnant, then not only she herself suffers, but also her child. It is known, for example, that stress during pregnancy can lead to a variety of consequences for the fetus - from preterm birth to neurological abnormalities. However, there is little research on how violence against a mother during pregnancy is related to the cognitive abilities of her child.

A team of scientists led by Richard Emsley of King's College London set out to estimate how many British women are being abused and to see how it affects the intelligence of their children.

Scientists worked with data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Of the 14,000 women who were pregnant in 1990–1992, 3,153 were selected who gave birth to one child, provided information about domestic violence, and agreed to have a child under 18 examined. The researchers assessed the level of intelligence of children using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale, a multi-level test that includes testing working memory, speech perception, understanding visual information and other skills.

18.6 percent of the women interviewed said they experienced violence between the start of pregnancy and up to six years after giving birth. At the same time, 17.6 percent reported psychological violence, and 6.8 percent physical. The researchers controlled for parental demographics and socioeconomic status, alcohol consumption and smoking during pregnancy, and maternal depression as side variables in evaluating the association between maternal abuse and child cognitive ability.

The researchers then counted the number of children with below average intelligence (less than 90 points) at age 8 in both groups. Among women who were not abused, 13 percent of children had below average general intelligence, 9.9 percent verbal intelligence, and 20.4 percent performative intelligence. Those who reported violence had 16.8, 12.1 and 25.6 percent, respectively. At the same time, physical violence, apparently, turned out to be more traumatic than psychological: from the first, children lost an average of 5. 6 points compared to their peers, and from the second - 2.9 points..

6 points compared to their peers, and from the second - 2.9 points..

In this way, scientists have demonstrated that the problem of domestic violence is still relevant in the UK and can even affect the mental abilities of the children of victims of women. However, the authors of the work note that not all cases of violence could be identified - due to the fact, for example, that women were afraid to talk about it or forgot when exactly it happened, so the real numbers may be different (most likely even more).

In 2018, scientists recorded a drop in the average level of intelligence - at least in Norway. Now there are technologies that allow you to choose a future child with the highest possible cognitive abilities based on genetic tests - however, as it turned out, they do not give a big win, and their accuracy is low. And about how intelligence is connected with other characteristics of a person, for example, appearance or love of music, we talked about in the material "Stop being clever. "

"

Polina Loseva

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Training of medical professionals to detect domestic violence during pregnancy Research paper in health sciences

2. Batoeva, D., T. Popov, E. Dragolova, Pedagogical and psychological diagnostics, Askoni-izdat, Sofia, 2006

", S., 1998, 383 p.

4. Desev, L., Psychology for the educational process, ed. SU - CIUU, S., 1993, 239 p.

5. Mikhailov, M. Professional teacher, orientation, suitability, realization, Sofia, 1996, ed. CIUU - UI „St. Kliment Ohridski", 119 pp.

6. Popov, T., Education in the field of public health (diagnostic aspects), Habilitation work, S., 2006, 277 pp.

7. Popov, T., Student kato subject for training, ed. "Vezni", S., 2006, 171 p.

8. Popov, T., Motivation for studying as a student, teaching in the system of public health, sp. "Healthy Management", 2006, vol. 6, book 2, pp. 55-59.

9. Radoslavova, M. , A. Velichkov, Methods for psychodiagnostics, ed. "Pandora Prim", S., 2005, 162 pp.

, A. Velichkov, Methods for psychodiagnostics, ed. "Pandora Prim", S., 2005, 162 pp.

© T. Popov, R. Yaneva, M. Aleksandrova, P. Gagova, 2013 DETECTION OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE DURING PREGNANCY

P. Trendafilova (Bulgaria, Sofia)

Abstract: Domestic violence is an increasingly common problem faced by health care workers in their daily work.This type of violence is used to gain power and control over the victim It can include all of the listed types of violence - physical, emotional, sexual, economic.About 95% of victims of domestic violence are women. Specific groups of women are particularly at risk of violence from their

partner. The main group among them are pregnant women - 25% of the victims were subjected to violence for the first time during pregnancy. The purpose of training on domestic violence during pregnancy is to help healthcare professionals identify, manage and deal with domestic violence, and to be able to effectively intervene and deal with it effectively.

Key words: domestic violence (DV), pregnancy, training of health professionals.

Domestic violence is an increasingly common problem faced by health workers in their daily work. Domestic violence is violence against a partner or domestic violence. It is characterized as a form of conflict resolution or the exercise of power, respectively, subordinating family members to one authority.

This type of violence is used to gain power and control over the victim. It can include all of the listed types of violence - physical, emotional, sexual, economic. Around 95% of victims of domestic violence are women. Domestic violence occurs with equal frequency in all socioeconomic, racial and ethnic groups. The community is found to be tolerant of violence. Research shows that at least once a year, one in two families experiences an episode of domestic violence. [3]

According to statistics, one in four women in the UK has been the victim of domestic violence at least once in her life (Mirrlees-Black, 1999). According to officially published data, on average every minute the police receive a report of domestic violence (Stanko, 2000). [10]

According to officially published data, on average every minute the police receive a report of domestic violence (Stanko, 2000). [10]

This crime has the highest recidivism rate in the UK (Kewshaw et al., 2000). [8]

Nearly half of all homicides against women are committed by a current or former partner and an average of two women per week

are killed by their intimate partner (Coleman et al., 2006). [2]

Studies carried out in parallel in Finland, Germany, Lithuania and Sweden found that 21% to 33% of women aged 20 to 59years have been physically abused by a current or former partner. In the last 12 months alone, violence by a current or former partner ranged from 3% in Germany and France to 5% in Sweden and 7% in Finland. For the same age group, data show that 11.5% of women in Finland, 6.5% in Germany, 7.5% in Lithuania and 6.2% in Sweden have experienced sexual violence at some time in their lives. [2]

Domestic violence is one of the major social and health problems faced by social and health professionals in their daily work. (Puchkov et al., 2009; Haggblom et al., 2005; Holt, 2003; Ferguson and O'Reilly, 2001; Humphries, 2000).

(Puchkov et al., 2009; Haggblom et al., 2005; Holt, 2003; Ferguson and O'Reilly, 2001; Humphries, 2000).

There are certain specific groups of women who are particularly at risk of violence from their partner. These are pregnant women (25% of the victims were the object of violence for the first time during pregnancy), women with mental health problems (up to 64% of hospitalized women with mental illness were physically abused), immigrant women, women with disabilities and older women [3] .

Pregnant women are particularly at risk of violence from their partner. Of all women subjected to domestic violence, 25% experienced violence for the first time during pregnancy.

It has been found that during pregnancy and at the beginning of family life with young children, the risk of violence increases. The risk of violence increases during maternity leave, compared to average violence statistics.

4% of women who have experienced abuse say that the abuse started during pregnancy. Another 4% report that the abuse started when their children were less than one year old. More than 10% of male despots

Another 4% report that the abuse started when their children were less than one year old. More than 10% of male despots

were violent towards their partners during pregnancy. (Heiskanen and Piispa 1998).

Violence against pregnant women often focuses on the abdomen and genitals, so that the injuries are not visible at first glance and are hidden under clothing. (Perttu S. and V. Kaselitz 2006). [9]

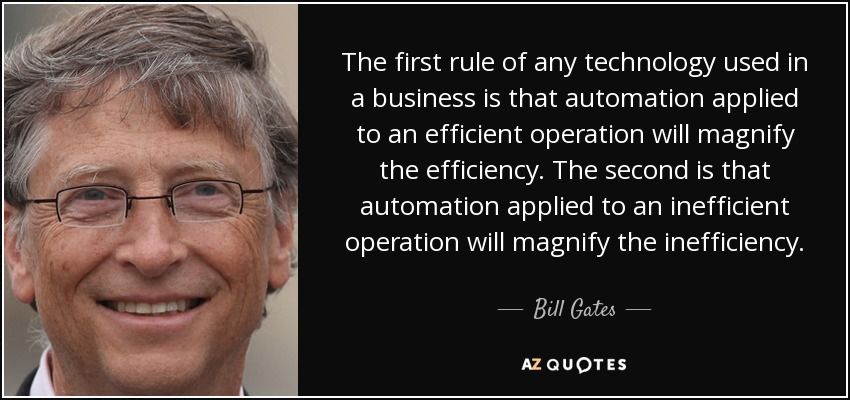

Health care professionals need to be more aware of the problems associated with domestic violence. Additional training is needed to identify the problem, prevent it, and provide support to victims and their families.

Most women do not tell their healthcare providers that they have been victims of intimate partner violence, even though they are the ones most likely to seek help. Because most healthcare professionals do not ask direct questions about intimate partner violence during routine check-ups, most cases go unnoticed (Backha et al., 2004). Questionnaires for screening the experience of health care professionals are useful in researching violence in intimate relationships and violence against children. These pregnancy violence questionnaires are based on studies in Finland and the Violence Study (AAS) (McFarlane and Parker, 1994).

These pregnancy violence questionnaires are based on studies in Finland and the Violence Study (AAS) (McFarlane and Parker, 1994).

Questionnaire focused on partner behavior. In addition to questions related to physical and sexual abuse, questions about the presence of controlling partner behavior and psychological abuse are also included. These are the ones that most often lead to physical abuse and are often signs of physical and/or sexual abuse [2] .

Advice for health professionals when identifying domestic violence among pregnant women:

> Environment should be created to encourage pregnant women to share more personal information;

> Creation of a sense of trust, safety and security in the person of a medical specialist;

> It is essential that the examination and the accompanying conversation with the pregnant woman be carried out in private, without the presence of a partner who is considered a potential rapist;

> Explain to the pregnant woman that domestic violence happens to many women;

> Questions are asked very carefully, carefully observing the behavior of the pregnant woman;

> She is very likely to renounce, but this does not necessarily mean that she is not a victim of violence;

> Avoid making any judgments about her behavior, her partner's behavior, etc. ;

;

> Reassure her that nothing she has told you will be discussed with her partner;

> Offer her different behaviors;

> Try to keep her as safe as possible;

> Don't compromise her safety for a minute;

> Discuss different strategies with her after she leaves the hospital;

> Check what she needs and try to be helpful;

> Refer her to appropriate professionals and non-governmental organizations who can help and support her;

> Give her information (telephone, address, etc.) where she can get help if needed (psychological support, housing, counseling, etc.).

> Find out her specific needs and provide support appropriate to those needs (eg, an immigrant woman who does not speak the language, you can offer language courses or counseling, etc.).

> Write down her address, phone number and try to contact her at the right time without putting her in danger;

> Explain to her partner that, given her condition, it may be necessary to visit her at home to monitor the pregnancy;

Accurate records of injuries and records of information received about the violence committed are of great importance for medical professionals. This is necessary for the following reasons:

This is necessary for the following reasons:

❖ These documents can be valuable evidence in court if a woman seeks legal protection or if a case is brought against her abusive partner.

❖ If you need a custody case or access to children if the partners live apart.

❖ The hospital record provides an overview of possible future injury, deterioration, miscarriage, premature birth, or death of the victim.

❖ Hospital visits provide valuable information about risk escalation, frequency of violence, and possible complications.

The way in which this documentation is maintained must be in accordance with the principles of good practice. We must not forget that this information is strictly confidential.

Documentation by health care providers should include the nature and location of injuries, the presence of new injuries, scars or traces of an old injury, the use of body maps for registration and detailed verbal description.

Brief descriptions of the victim (pregnant woman) about how she was injured and who caused her injuries should be included in the documentation. It should be borne in mind that victims are often reluctant to share such information. Often they will lie about how the "incident" happened, fearing repercussions if the abuser finds out. The most common explanations are: "I fell down the stairs." The name of the offender and his relationship with the victim (patient) should appear in the dossier of the pregnant woman. If possible, record the time, date and place of the incident and

It should be borne in mind that victims are often reluctant to share such information. Often they will lie about how the "incident" happened, fearing repercussions if the abuser finds out. The most common explanations are: "I fell down the stairs." The name of the offender and his relationship with the victim (patient) should appear in the dossier of the pregnant woman. If possible, record the time, date and place of the incident and

possible witnesses, if any. Information about whether the police were called and about the appearance of the police, if any. Information about the weapon used, if any, and other details.

It should be noted here if there is a history of past relationship abuse (according to the victim) and when it happened, if any, as well as the circumstances associated with it.

If there are discrepancies and inconsistencies between the information provided by the victim and injuries, as well as the existing potential for their occurrence, the documentation should contain this information.

Abusive relationships often alternate between periods of aggression and abuse and peaceful periods. This phenomenon is known in the literature as "intermediate reinforcement". These so-called "light periods in a relationship" lead to emotional attachment that reduces the victim's ability to make independent decisions.

Periods of violence bring despair and helplessness, while periods of peace bring relief and hope. (Council on the Status of Women in the Northeast Territories, 1995)

Individual counseling is essential for a safe and effective practice. Strengths-based core principles are appropriate for such consultations because they reinforce a woman's own strategies and therefore increase her self-esteem and confidence to help her make long-term decisions for her own safety and the safety of her children. But counseling should not stop after a woman has received a protection order or left her partner. This is the most dangerous time for an injured woman, the time when she needs the most protection. A woman's partner may urge her to return to him to give their relationship another chance, or she may be tortured and harassed by him. There may be ongoing legal difficulties in accessing children. All these

A woman's partner may urge her to return to him to give their relationship another chance, or she may be tortured and harassed by him. There may be ongoing legal difficulties in accessing children. All these

Problems can interfere with her decision making and require constant support and a "safe place" where she can discuss her fears and concerns.

While some women may leave their partner after the first time she is physically hurt, most women begin a process in which they seek to find meaning in the abuse in order to continue their relationship and maintain the integrity of their home and family. In addition to the desire to keep the family together, women point to a number of legal, economic and social barriers to separation. [3]

In conclusion, we can say that all these incidents and possible risks make the work of medical experts even more difficult. That is why they must be well trained and prepared for specific work with victims of domestic violence. Early recognition of the symptoms of abuse can be critical in ensuring the safety of pregnant women who are victims of violence and the health of their unborn child.

References:

1. Allen M., H. Hellbernd, S. Huschka, S. Jenner, S. Perttu, T. Savola. Teachers of social and health hernias will cut violence. Leadership for teachers. Edited by P. Trendafilov, ISBN 978-952-10-6208-7, 2010.

2. Allen M., S. Perttu. Handbook for a teacher of social and health care. Edited by P. Trendafilova, ISBN 978-952-10-6209-4, 2010.

3. Trendafilova P. Violence to cross intimia partner (specific features, prerequisites for the emergence, identification and prevention). Monograph. ISBN: 978-954-2918-516, S., 2012.

4. Domestic Violence: A Health Issue: Guidelines for Hospital Staff (2004) St. Columcille's Hospital, Dublin.

5. Haggblom, A.M.E., Hallberg, L.R.M. and Moller, A.R. (2005) Nurses' Attitudes and Practices towards abused women. Nursing and Health Sciences7, 235-242.

6. Heise, L. and Garcia-Moreno, C. (2002) 'Violence by Intimate Partners', in E. Krug, L. Dahlberg, J.A. Mercy, A.B. Zwi and R. Lozano (eds), World Report on Violence and Health, Geneva: WHO.

7. Humphreys, C. and Stanley, S. (eds) Domestic Violence and Child Protection: Directions for Good Practice, London: Jessica Kingsley, 2006.

8. Kewshaw, C., Budd, T., Kinshott, G., Mattison, J. Mayhew, P. and Myhill, A (2000) The 2000 British Crime Survey: England and Wales. Home Office Statistical Bulletin 18/100. London. home office.

9. Perttu., S and Kaselitz 2006, V. Addressing Intimate Partner Violence: Guidelines for Health Professionals in Maternity and Child Health Care University of Helsinki.

10. Stanko, E. (2000) 'The Day to Count: A Snapshot of the Impact of Domestic Violence in the UK', Criminal Justice, 1, 2.

11. Tufts, K. A., Clements, P. T. and Karlowicz, K. A. Integrating intimate partner violence content across curricula: Developing a new generation of Nurse Educators. Nurse Education Today, 29, 2009, 40-47.

12. WHO: World Report on Violence and Health, E. Krug, L. Dahlberg, J.A. Mercy, A.B. Zwi and R. Lozano (eds), Geneva, 2002.