Childbirth in human

What happens to your body during childbirth

What happens to your body during childbirth | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content7-minute read

Listen

Key facts

- Female bodies are designed to give birth, and changes during the last weeks of pregnancy help prepare your body for labour and delivery.

- The shape of the pelvis, hormones, powerful muscles and more all work together to help you bring your baby into the world.

- Many different types of hormones work together to prepare your body for labour and birth.

- Your baby’s skull can also change shape to better pass through your birth canal.

How does my body prepare for labour?

Here are some of the ways your body will prepare both you and your baby for the birth ahead.

Braxton Hicks contractions

In the weeks or days before you start having proper contractions, you may experience Braxton Hicks contractions. This is your uterus tightening then relaxing. These contractions don't usually hurt and are thought to help your uterus and cervix get ready for labour. Braxton Hicks contractions are sometimes referred to as 'false labour'.

Braxton Hicks contractions may become more regular as you get closer to the time of birth. Unlike labour contractions, they don't change the shape of the cervix. Your midwife can tell you if you're experiencing Braxton Hicks contractions or if you are in labour by doing a vaginal examination.

Changes to the cervix

As labour gets closer, your cervix softens and becomes thinner, getting ready to dilate (widen). This will allow your baby to enter your vagina during birth. You may also see a ‘show’, which is a pinkish plug of mucus that may be bloodstained.

Engagement

Your baby may move further down your pelvis as the head engages, or sits in place over your cervix, ready for the birth. You may feel that you have more room to breathe after the baby has moved down. This is called ‘lightening’.

You may feel that you have more room to breathe after the baby has moved down. This is called ‘lightening’.

Rupture of the membranes, or ‘waters breaking’

During labour, the sac of amniotic fluid containing the baby breaks, and the fluid leaks (or gushes) out of the vagina. This is called rupture of the membranes or 'waters breaking'. In some cases, this happens before labour.

Let your maternity team know when your waters have broken and take notice of the colour of the fluid. It is usually clear or tinged pink. If it is green or red, tell your maternity team since this could mean the baby is having problems.

If your labour doesn’t start within 24 hours of your waters breaking, there is a risk of infection. If this happens, your doctor or midwife may recommend inducing your labour.

How will I know when labour has started?

Movies often show labour starting with sudden, painful contractions and a rush to hospital. In real life, labour usually starts gradually. It’s common not to be sure if your labour has actually started.

It’s common not to be sure if your labour has actually started.

You may feel restless, have back pain or period-like pain, or digestive issues such as diarrhoea.

Labour officially begins with contractions, which start working to open up (dilate) the cervix. It’s a good idea to phone your midwife when your contractions start. However, you may not be encouraged to come to the hospital or birthing centre until your contractions are closer together.

In preparation for labour, your baby may move further down your pelvis as the head engages, or sits in place over your cervix.You and your baby’s bodies work together during labour and birth.

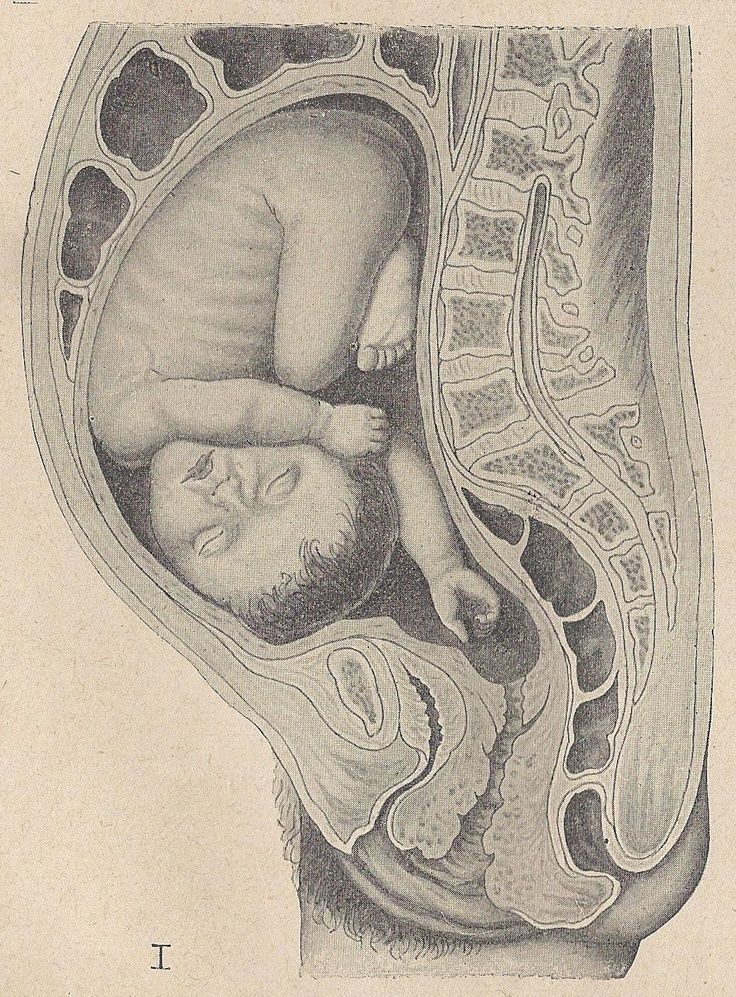

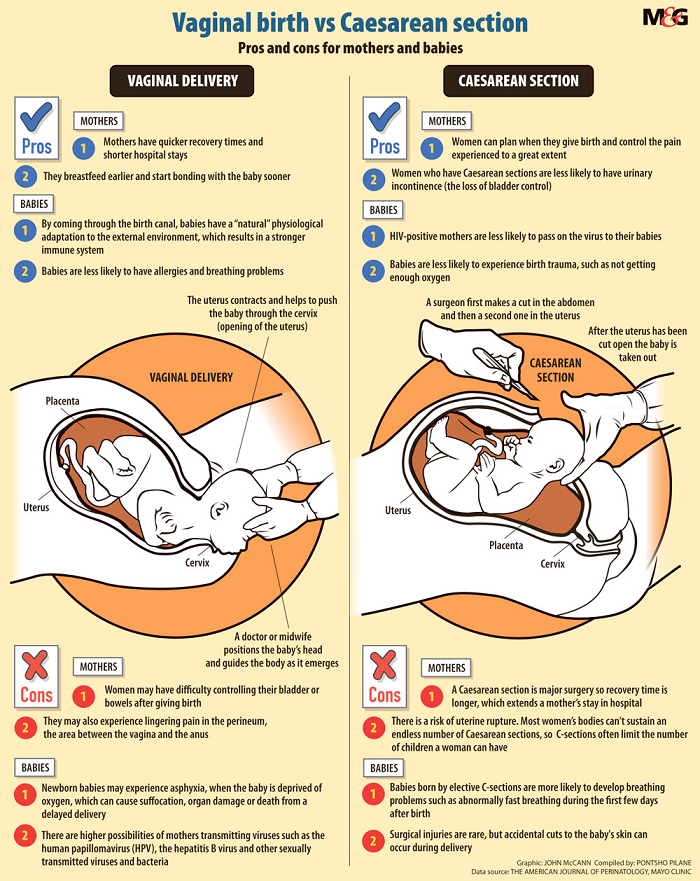

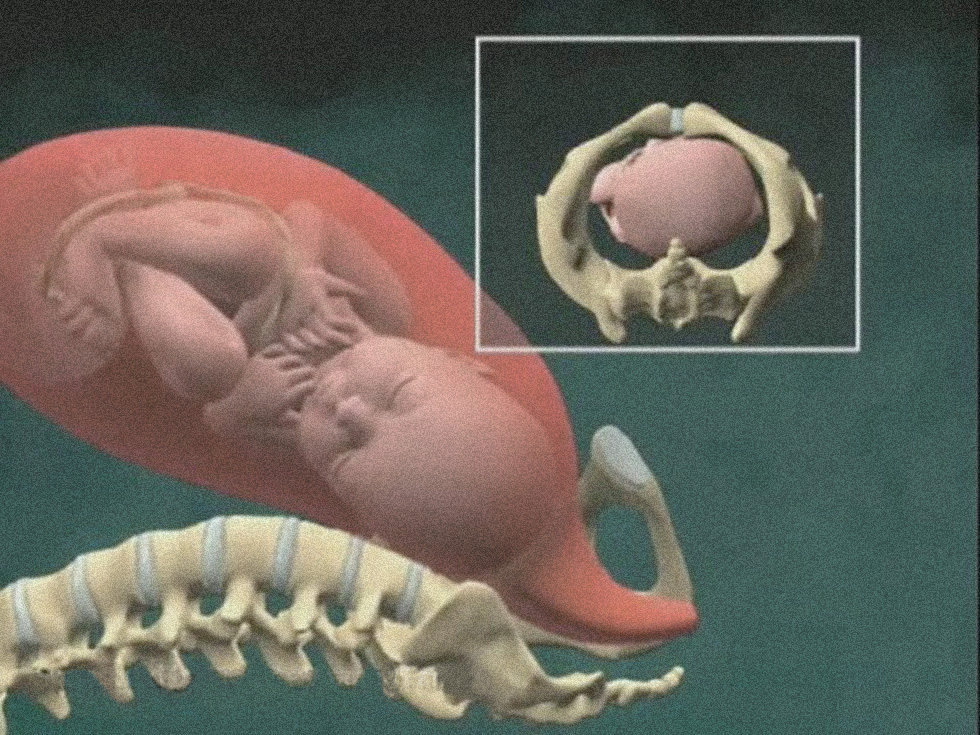

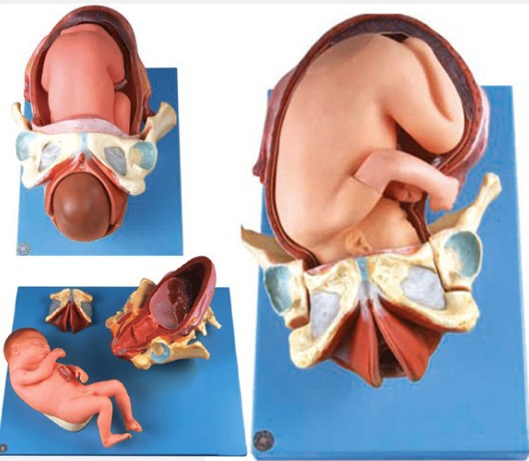

Your pelvis is located between your hip bones. Females typically have wider, flatter pelvises than males, as well as a wider pelvic cavity (hole) to allow a baby to pass through.

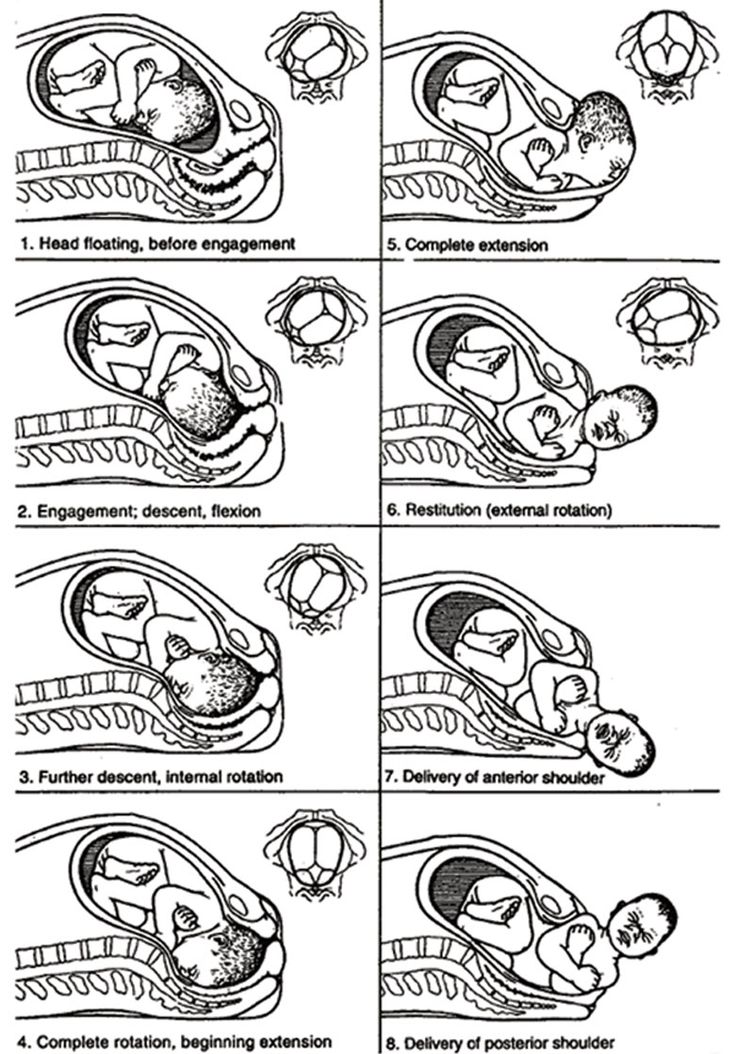

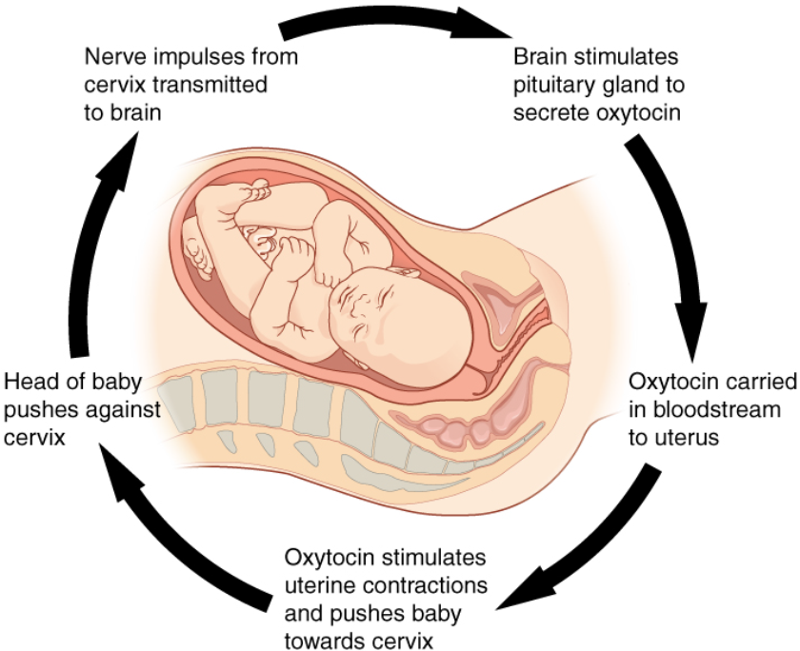

During childbirth, the muscles at the top of your uterus contract and push your baby towards your cervix. If your baby is facing head-down, the head will press on your cervix.

This, along with the release of the hormone oxytocin (see 'How hormones help you give birth', below), brings on contractions. The bones and ligaments of your pelvis also move or stretch as the baby travels into the vagina.

Your baby’s skull is made up of 5 separate bones, which can cross over each other during labour. This allows your baby's head to fit more easily through your birth canal.

Which hormones help me give birth?

Your body produces hormones that trigger changes in your body before, during and after childbirth. Here's how they work to help you deliver your baby.

- Prostaglandin — Before childbirth, a higher level of prostaglandin will help open the cervix and make your body more receptive to another important hormone, oxytocin.

- Oxytocin — This hormone causes contractions during labour, as well as the contractions that deliver the placenta after the baby is born, and during breastfeeding.

- Relaxin — The hormone relaxin helps soften and stretch the cervix for birth.

It helps your waters break and allows the ligaments in your pelvis to stretch to allow the baby to come through.

It helps your waters break and allows the ligaments in your pelvis to stretch to allow the baby to come through. - Beta-endorphins — During childbirth, this type of endorphin helps with pain relief and may cause you to feel joy or euphoria.

- Adrenaline and noradrenaline — These ‘fight or flight’ hormones are released just before birth, causing several strong contractions and a surge of energy that help you birth your baby.

When childbirth doesn’t go to plan

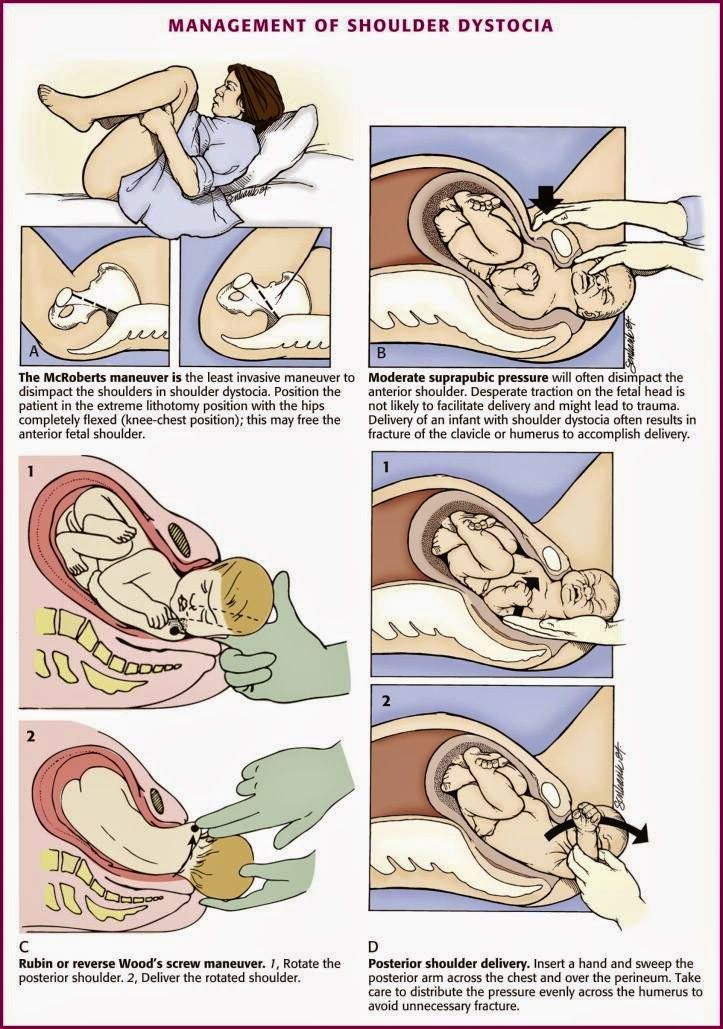

Despite your best efforts, sometimes, labour and birth do not go to plan. This could be because of complications before the labour, such as your waters breaking early, problems with your placenta, or issues with your baby’s position, health or progress during labour. If this happens, your midwife or doctor may recommend intervening to ensure a safe birth for both you and your baby.

Some of the more common interventions include:

- external cephalic version (turning your baby so they are in a better position for birth)

- induction or augmentation of labour

- assisted delivery

- episiotomy

- caesarean section

It’s your choice whether to have interventions in your labour. You can ask your doctor or midwife about the benefits and risks of any intervention they recommend.

You can ask your doctor or midwife about the benefits and risks of any intervention they recommend.

Talk to your doctor or midwife if you have questions about your body. They can give you more information and help you understand what you're experiencing.

You can also call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby for free advice, support and guidance from our maternal child health nurses.

Speak to a maternal child health nurse

Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436 or video call. Available 7am to midnight (AET), 7 days a week.

Sources:

Mater Mothers’ Hospital (Labour and birth information), National Childbirth Trust (Hormones in labour: oxytocin and the others – how they work), NSW Government (Having a baby), QLD Health (How your body prepares for labour), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Labour and birth), Stat Pearls (Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis), You and Your Hormones from the Society for Endocrinology (Hormones of pregnancy and labour)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: August 2022

Back To Top

Need more information?

Pregnancy: premature labour & birth | Raising Children Network

Are you likely to be having a premature birth? Here’s all you need to know about preparing for and recovering from premature labour and birth.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Pregnancy: labour & birth | Raising Children Network

Pregnant? Here’s all you need to know to decide where to give birth and prepare for labour and vaginal birth or caesarean birth.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Labour & birth: what to expect | Raising Children Network

Early labour signs include a show, waters breaking and pain. During labour, your contractions increase and your cervix dilates, so you can birth your baby.

During labour, your contractions increase and your cervix dilates, so you can birth your baby.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Premature birth & premature babies | Raising Children Network

This essential guide for parents of premature babies covers gestational age, premature birth risk factors, premature labour and premature development.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Premature birth: questions & checklist | Raising Children Network

Our checklist has answers to questions about premature birth and labour, covering where and how premature babies are born, and things to ask medical staff.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Labour and Birth

Read more on RANZCOG - Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists website

Developing a birth plan - Better Health Channel

A birth plan is a written summary of your preferences for when you are in labour and giving birth.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Premature babies and birth | Raising Children Network

Premature babies are born before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Our essential guide covers premature birth, babies, development, NICU and more.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Premature birth: emotional preparation | Raising Children Network

If you know your baby will be born early, you can prepare yourself mentally and emotionally. Practise relaxation and take a tour of the NICU. Find out more.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Dads: premature birth and premature babies | Raising Children Network

After a premature birth, it can be hard for dads. Our dads guide to premature babies and birth covers feelings, bonding, and getting involved with your baby.

Our dads guide to premature babies and birth covers feelings, bonding, and getting involved with your baby.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Birth | Definition, Stages, Complications, & Facts

birth

See all media

- Key People:

- Virginia Apgar Hugh Chamberlen, the Elder Sir James Young Simpson, 1st Baronet Walter Channing Gertie F. Marx

- Related Topics:

- multiple birth presentation natural childbirth labour dilatation

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

birth, also called childbirth or parturition, process of bringing forth a child from the uterus, or womb. The prior development of the child in the uterus is described in the article human embryology. The process and series of changes that take place in a woman’s organs and tissues as a result of the developing fetus are discussed in the article pregnancy.

The prior development of the child in the uterus is described in the article human embryology. The process and series of changes that take place in a woman’s organs and tissues as a result of the developing fetus are discussed in the article pregnancy.

Initiation of labour

Despite decades of research, the events leading to the initiation of labour in humans remain unclear. It is suspected that biochemical substances produced by the fetus induce labour. In addition, the timing of the production of these substances and their interaction with placental and maternal biochemical factors appear to influence this process. Among the most studied of these biochemical substances are fetal hormones such as oxytocin and placental inflammatory molecules. Increased placental and maternal production of inflammatory molecules in late pregnancy has been strongly linked to the initiation of labour. Hormonelike substances called prostaglandins, which are produced by the placenta in response to various biochemical signals, can induce inflammation and are present in increased levels during labour. Several factors that increase the production of prostaglandins include oxytocin, which stimulates the force and frequency of uterine contractions, and a fetal lung protein called surfactant protein A (SP-A). Surfactant production in the fetal lung does not begin until the last stages of gestation, when the fetus prepares for air breathing; this transition may act as an important labour switch.

Several factors that increase the production of prostaglandins include oxytocin, which stimulates the force and frequency of uterine contractions, and a fetal lung protein called surfactant protein A (SP-A). Surfactant production in the fetal lung does not begin until the last stages of gestation, when the fetus prepares for air breathing; this transition may act as an important labour switch.

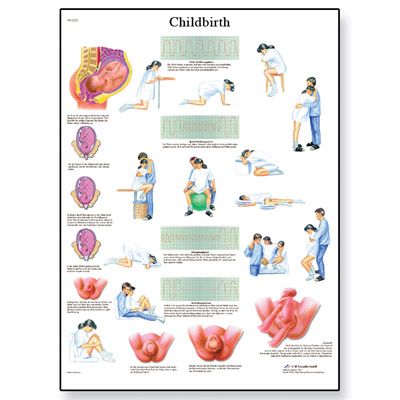

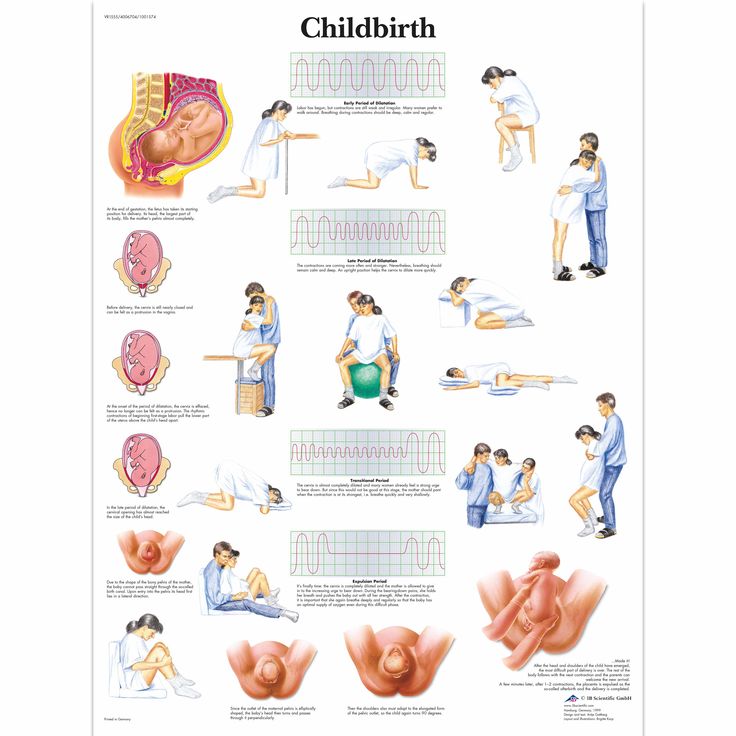

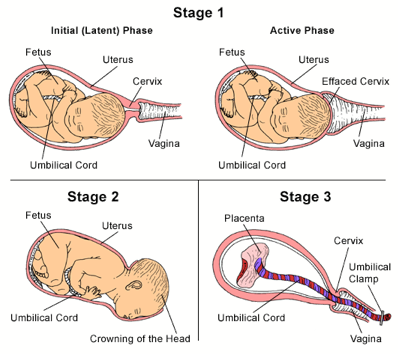

The stages of labour

First stage: dilatation

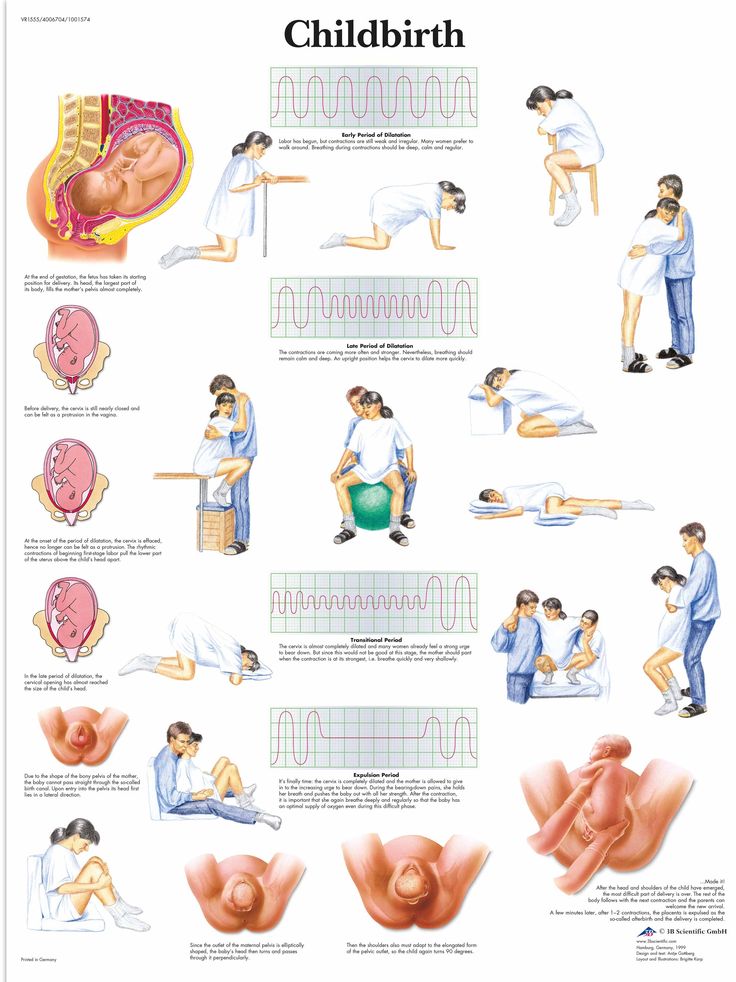

Early in labour, uterine contractions, or labour pains, occur at intervals of 20 to 30 minutes and last about 40 seconds. They are then accompanied by slight pain, which usually is felt in the small of the back.

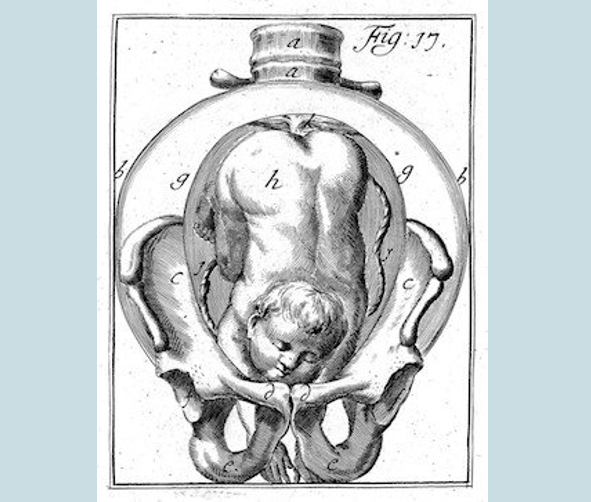

As labour progresses, those contractions become more intense and progressively increase in frequency until, at the end of the first stage, when dilatation is complete, they recur about every three minutes and are quite severe. With each contraction a twofold effect is produced to facilitate the dilatation, or opening, of the cervix. Because the uterus is a muscular organ containing a fluid-filled sac called the amnion (or “bag of waters”) that more or less surrounds the child, contraction of the musculature of its walls should diminish its cavity and compress its contents. Because its contents are quite incompressible, however, they are forced in the direction of least resistance, which is in the direction of the isthmus, or upper opening of the neck of the uterus, and are driven, like a wedge, farther and farther into this opening. In addition to forcing the uterine contents in the direction of the cervix, shortening of the muscle fibres that are attached to the neck of the uterus tends to pull those tissues upward and away from the opening and thus adds to its enlargement. By this combined action each contraction of the uterus not only forces the amnion and fetus downward against the dilating neck of the uterus but also pulls the resisting walls of the latter upward over the advancing amnion, presenting part of the child.

Because the uterus is a muscular organ containing a fluid-filled sac called the amnion (or “bag of waters”) that more or less surrounds the child, contraction of the musculature of its walls should diminish its cavity and compress its contents. Because its contents are quite incompressible, however, they are forced in the direction of least resistance, which is in the direction of the isthmus, or upper opening of the neck of the uterus, and are driven, like a wedge, farther and farther into this opening. In addition to forcing the uterine contents in the direction of the cervix, shortening of the muscle fibres that are attached to the neck of the uterus tends to pull those tissues upward and away from the opening and thus adds to its enlargement. By this combined action each contraction of the uterus not only forces the amnion and fetus downward against the dilating neck of the uterus but also pulls the resisting walls of the latter upward over the advancing amnion, presenting part of the child.

In spite of this seemingly efficacious mechanism, the duration of the first stage of labour is rather prolonged, especially in women who are in labour for the first time. In such women the average time required for the completion of the stage of dilatation is between 13 and 14 hours, while in women who have previously given birth to children the average is 8 to 9 hours. Not only does a previous labour tend to shorten this stage, but the tendency often increases with succeeding pregnancies, with the result that a woman who has given birth to three or four children may have a first stage of one hour or less in her next labour.

The first stage of labour is notably prolonged in women who become pregnant for the first time after age 35, because the cervix dilates less readily. A similar delay is to be anticipated in cases in which the cervix is extensively scarred as a result of previous labours, amputation, deep cauterization, or any other surgical procedure on the cervix. Even a woman who has borne several children and whose cervix, accordingly, should dilate readily may have a prolonged first stage if the uterine contractions are weak and infrequent or if the child lies in an inconvenient position for delivery and, as a direct consequence, cannot be forced into the mother’s pelvis.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

On the other hand, the early rupturing of the amnion often increases the strength and frequency of the labour pains and thereby shortens the stage of dilatation; occasionally, premature loss of the amniotic fluid leads to molding of the uterus about the child and thereby delays dilatation by preventing the child’s normal descent into the pelvis. Just as an abnormal position of the child and molding of the uterus may prevent the normal descent of the child, an abnormally large child or an abnormally small pelvis may interfere with the descent of the child and prolong the first stage of labour.

Second stage: expulsion

About the time that the cervix becomes fully dilated, the amnion breaks, and the force of the involuntary uterine contractions may be augmented by voluntary bearing-down efforts of the mother. With each labour pain, she can take a deep breath and then contract her abdominal muscles. The increased intra-abdominal pressure thus produced may equal or exceed the force of the uterine contractions. These bearing-down efforts may double the effectiveness of the uterine contractions.

The increased intra-abdominal pressure thus produced may equal or exceed the force of the uterine contractions. These bearing-down efforts may double the effectiveness of the uterine contractions.

As the child descends into and passes through the birth canal, the sensation of pain is often increased. This condition is especially true in the terminal phase of the stage of expulsion, when the child’s head distends and dilates the maternal tissues as it is being born.

How to behave in childbirth? Learning to give birth quickly and with problems

Childbirth is a natural process laid down by nature. The whole sequence of events that take place during this period is predetermined, but by your actions you can either speed up the birth of a baby, or complicate his birth.

Childbirth is the final and most important stage of pregnancy. How you behave, how accurately and skillfully you follow the instructions of the obstetrician, depends on how you will feel and how quickly your baby will be born. What does a newborn need to know? Let's try to answer the most important questions.

What does a newborn need to know? Let's try to answer the most important questions.

1. When is it time to go to the maternity hospital?

Childbirth is a natural result of hormonal changes that occur in your body during the final stages of pregnancy. The sagging belly and heaviness in its lower part and the lumbar region speak of the imminent denouement of the story. Periodically, weak contractions occur, the stomach tenses and pulls down, but these sensations quickly pass, the uterus relaxes again and becomes soft. Such contractions are harbingers of childbirth, but they are far from real labor activity.

The signal to call an ambulance should be sufficiently strong contractions that are repeated at regular intervals, the appearance of mucous secretions from the genital tract, slightly stained with blood, or the outflow of amniotic fluid.

2. First stage of childbirth: we breathe for two!

From the moment the contractions become regular, the first stage of labor begins, during which the strength, frequency and duration of uterine spasms increases and the cervix opens.

During spastic contraction of the uterine muscle fibers, the blood vessels that carry arterial blood to the placenta and fetus are compressed. The fetus begins to experience a lack of oxygen, and this involuntarily makes you breathe deeper. The reflex increase in the rate of contractions of your heart will ensure the delivery of oxygen to the child. Nature has provided that these processes take place regardless of your consciousness, but you should not completely rely on it.

In the first stage of labor, during each contraction, you need to breathe calmly and deeply, trying not to hold your breath while inhaling. At the same time, the air should fill the upper sections of the lungs, as if raising the chest. You need to inhale through the nose, slowly and smoothly, exhale through the mouth, just as evenly.

3. Auto-training in the prenatal ward

To speed up the opening of the cervix, you need to walk more, but sitting is not recommended, while blood flow in the limbs is disturbed and venous blood stagnation occurs in the pelvis. From time to time it is useful to lie on your side, stroking your lower abdomen with both hands in the direction from the center to the sides, focusing on breathing and saying to yourself: "I am calm, I am in control of the situation, each contraction brings me closer to the birth of a baby."

From time to time it is useful to lie on your side, stroking your lower abdomen with both hands in the direction from the center to the sides, focusing on breathing and saying to yourself: "I am calm, I am in control of the situation, each contraction brings me closer to the birth of a baby."

4. To relieve pain

Acupressure of the lower back can help relieve pain. Find the outer corners of the sacral rhombus on your lower back and massage these points with clenched fists.

Monitor the frequency and duration of contractions and if they weaken or sharply increase, immediately inform your doctor. In case of severe pain, you can ask for an anesthetic, but you should remember that you should not take the medicine too often, this is fraught with narcotic depression of the newborn and a decrease in his adaptive abilities.

If dilatation of the cervix causes reflex vomiting, rinse the mouth with water and then drink a few sips to replace the lost fluid. Do not drink a lot, this can provoke a recurrence of vomiting.

Do not drink a lot, this can provoke a recurrence of vomiting.

5. The maternity ward is not a place for tantrums

They say that difficult childbirth is a person's retribution for walking upright. Childbirth is actually a painful process, but the presence of reason allows us, representatives of the genus Homo sapiens, to control our emotions. Screaming, crying, tantrums and swearing have no place in the maternity ward. This creates a tense environment, interferes with the normal course of childbirth, complicates diagnostic and therapeutic measures, and ultimately affects their outcome.

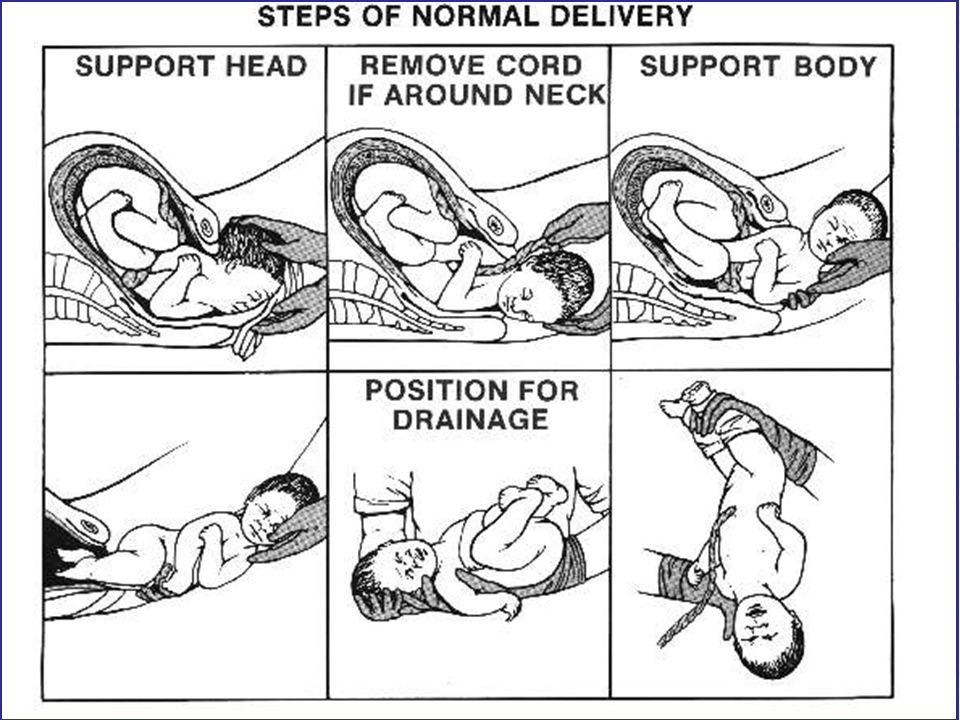

6. Second stage of labor - pushing and expulsion of the fetus

After the baby's head slips through the dilated cervix and finds itself on the bottom of the pelvis, the pushing period of labor begins. At this time, there is a desire to push, as it usually happens during a bowel movement, but at the same time many times stronger. At first, the attempts are controllable, they can be "breathed", but by the beginning of the third stage of labor, the expulsion of the fetus, they become unbearable.

With the beginning of the straining period, you will be transferred to the delivery room. Having settled down on the delivery table, rest your feet on the special steps, firmly grasp the handrails and wait for the midwife's command.

While pushing, inhale deeply, close your mouth, clench your lips tightly, pull the handrails of the delivery table towards you and direct all the exhalation energy down, squeezing the fetus out of you. When the top of the baby appears from the genital slit, the midwife will ask you to ease your efforts. With gentle movements of her hands, she will first release the baby’s forehead, then his face and chin, after which she will ask you to push again. At the moment of the next attempt, the baby's shoulders and torso will be born. After the newborn is born, you can breathe freely and rest a little, but the birth is not over.

7. Third stage of labor and final

Third stage of labor - afterbirth. At this time, weak contractions are observed, due to which the fetal membranes gradually exfoliate from the walls of the uterus.

At this time, weak contractions are observed, due to which the fetal membranes gradually exfoliate from the walls of the uterus.

About 10 minutes after your baby is born, your midwife will ask you to push again to deliver your afterbirth. The doctor will carefully examine it and make sure that all parts of the membranes have come out. After that, with the help of mirrors, he will examine the cervix and make sure that it is intact. If necessary, all tears will be closed with absorbable sutures.

You will have to spend another couple of hours in the delivery room with an ice-filled bladder on your stomach. To quickly contract the uterus, you will be given injections of special drugs. When the threat of postpartum hemorrhage has passed, you will be transferred to the postpartum ward to the baby.

Childbirth completed. Ahead of the postpartum period, during which your body will recover after pregnancy.

More details on Medkrug. RU: http://www.medkrug.ru/article/show/kak_pravilno_vesti_sebja_v_rodah_uchimsja_rozhat_bystro_i_problem

RU: http://www.medkrug.ru/article/show/kak_pravilno_vesti_sebja_v_rodah_uchimsja_rozhat_bystro_i_problem

Source: http://www.medkrug.ru/

Why childbirth is so hard and dangerous

- Colin Barras

- BBC Earth

Sign up for our mailing list ” Context”: it will help you make sense of events. Image credit: iStock However, recent research shows that this is not the only issue, says columnist BBC Earth .

The birth of a child is a long and painful process, and sometimes deadly. According to the World Health Organization, about 830 women die every day due to complications during pregnancy and childbirth (which, however, is 44% lower than in 1990).

"These statistics are astounding," says Jonathan Wells of University College London, who studies infant nutrition. "Female mammals have never had to pay such a high price for offspring. "

"

- Russian woman who gave birth to 69 children: truth or fiction?

- Pregnancy and childbirth in the UK: free and without a doctor

- Can you determine the sex of a child by the size of the mother's belly?

- "Age is one day": the first hours of a new life

But why is childbirth so dangerous for women? And what can we do to reduce the death rate?

Scientists first began to think about the causes of such dramatic childbirth in women in the middle of the 20th century. They quickly, as it seemed then, found an explanation.

Problems with childbearing began as early as the earliest members of our evolutionary lineage, the hominins, who diverged from other primates about seven million years ago.

These were animals that had little in common with us today, except, perhaps, for the fact that already in those distant times, like us, they walked on two legs.

Photo copyright JUAN MANUEL BORRERO/naturepl.com

Photo captionHominins have been moving upright for millions of years

Walking upright caused the hominin skeleton to change - it stretched, and this affected the shape of the pelvis.

In most primates, the birth canal is relatively straight. Among the hominins, they soon changed quite markedly. The hips became narrower, and the birth canal curved.

Thus, at the dawn of our history, hominin babies had to twist and turn in order to squeeze through the birth canal. This made the birth process very difficult.

But things soon got worse.

About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to change again. They lost their ape-like features and became more like modern humans.

Their bodies have become a little longer, their arms have become shorter, and their brains have noticeably enlarged. And this last detail was bad news especially for women.

Image copyright, Science Photo Library

Image caption,About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to lose their ape-like features and become more like modern humans

It seems that evolution has begun to contradict itself. On the one hand, the pelvis of women had to narrow so that they could move on two legs, on the other hand, the babies they carried had an enlarged head, complicating the process of passing through the already narrow birth canal.

Childbirth has become an incredibly painful and potentially dangerous business, which it has remained to this day.

In 1960, the anthropologist Sherwood Washburn called this theory the "obstetrical dilemma" and this explanation satisfied many scientists. But not everyone.

Holly Dunsworth of the University of Rhode Island was initially fascinated by Washburn's theory, but later realized that a lot of it didn't add up.

According to Washburn, when the human brain expanded two million years ago, the woman's body began to adapt to this, and the duration of pregnancy was noticeably reduced.

Photo credit, Science Photo Library/Alamy

Photo caption,Many women use pain relief during childbirth

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

And it seems like a pretty logical hypothesis: babies began to be born at an earlier stage of development, and anyone who has ever seen a newborn baby will attest to how helpless and vulnerable he is.

However, Dunsworth believes that this is simply not true.

"Our babies are born fairly large, and female pregnancies last 37 days longer than monkeys of the same size," explains the researcher.

The same applies to the size of the brain. Females give birth to babies with larger heads than females of other primates, with about the same body weight as females. And this means that the key points of Washburn's hypothesis are false.

Females give birth to babies with larger heads than females of other primates, with about the same body weight as females. And this means that the key points of Washburn's hypothesis are false.

And that's not all. The central assumption of the obstetrical dilemma is that the size and shape of the human pelvis, in particular in women, has changed greatly due to our habit of walking in an upright position.

However, if evolution were to solve the problem of childbirth in humans, it would certainly have already made women's hips and, accordingly, the birth canal a little wider.

In this case, our ability to walk on two legs would not suffer at all.

Photo credit, Visuals Unlimited/naturepl.com

Photo caption,Men's (left) and women's (right) pelvises

In 2015, researchers from Harvard University conducted an experiment that involved men and women with different body types.

The researchers observed the physical activity of volunteers in the lab and found that those with wider hips had no problem walking or running.

So, if nature, through evolution, made women's hips a little wider and thus facilitated childbearing, women's ability to move would not deteriorate.

According to Dunsworth, the duration of pregnancy in women is not determined by the size of the baby's brain, as the obstetric dilemma suggests.

The fact is that a woman's body is simply not able to feed a fetus that requires too much energy for longer than 39-40 weeks.

So, the reason for this length of pregnancy is not the difficulty of passing the child through the birth canal, as Washburn believed.

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Fetus on CT scan

What then is the true cause of difficult labor in women? In 2012, researcher Jonathan Wells of University College London and his team began to study the history of childbirth and came to a startling conclusion.

For most of human evolution, it was obviously much easier to have a baby than it is now.

From the little evidence that remains today, it follows that in early hunter-gatherer societies, childbirth was one of the smallest problems.

Archaeologists find almost no skeletons of babies from this period, which indicates a relatively low mortality rate in early childhood.

But the situation changed dramatically a few thousand years ago, when people switched to a sedentary lifestyle.

Many more newborn bones appear in the archaeological record from the early agricultural era.

Photo copyright, Volker Steger/4 million years of man/SPL

Photo caption,Homo erectus, the immediate ancestor of modern humans, could have had a much easier birth process…

On the one hand, living in a more populous community led to outbreak of infectious diseases, and newborns, as the most vulnerable, became their victims.

On the other hand, the diet of farmers with a high content of carbohydrates began to differ markedly from the diet of hunter-gatherers, which was dominated by proteins.

This provoked changes in the body structure: the agriculturalists, as evidenced by archaeological finds, were significantly shorter than the hunter-gatherers.

And scientists who study childbirth are well aware that the shape and size of a woman's pelvis directly depends on her height.

The smaller the woman, the narrower her hips - hence, the transition to agriculture has complicated the process of childbearing.

On the other hand, a carbohydrate-rich diet has made babies gain weight faster in the womb, and it is much more difficult to give birth to a large baby.

Photo copyright, Jose Antonio Penas/Science Photo Library

Photo caption,Farming has once again changed our bodies

Thus, about 10 thousand years ago, childbirth, which for millions of years was a relatively easy process for humans, suddenly become a problem.

However, according to Holly Dunsworth, this is not the end of the story.

Scientific evidence shows that a woman's pelvis is most conducive to childbirth around the age of 20, when she reaches peak fertility, and remains so until about 40 years of age.

After that, it gradually changes its shape, preparing for menopause, and becomes less suitable for the birth of a child.

The question arises: if so many evolutionary factors influenced the characteristics of childbirth, maybe this process continues to this day?

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Pregnancy is sometimes debilitating for a woman

In December 2016, scientists Fischer and Mittereker published a sensational paper on this topic.

Previous studies have suggested that larger babies are more likely to survive, and that infant size at birth is to some extent a hereditary factor.

The growth of a medium-sized fetus is evolutionarily limited by the width of the female pelvis.