Baby birth up close

Woman giving birth: Live birth video

Narrator: Samiyyah is the owner of a day spa in Philadelphia. She is 38 weeks pregnant with her second child.

Samiyyah: With the first pregnancy, I delivered in a hospital, and it was very restricting, you know, being confined to the bed, not being able to, you know, move when I felt my body wanted me to do certain things.

Narrator: For her son Safi's birth, she was given pitocin to speed up labor, an epidural for pain management, and an episiotomy (a surgical cut to widen the vaginal opening).

This time, she's planning a natural delivery -- without pain medication and other medical interventions -- at a birth center.

Samiyyah: Yes, I've been told that I am completely crazy for being, you know, for not having the drugs, but I've been there and I didn't like it, so I figured I would try this. It's healthier for the baby; it's healthier for me. So why not? I mean, women, we were designed to do this.

Narrator: Seven days after her due date, Samiyyah's labor kicks into gear. At the birth center in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Julia Rasch, a licensed nurse/midwife, performs an internal exam and starts an IV line to give Samiyyah a dose of antibiotics, since she's positive for Group B strep.

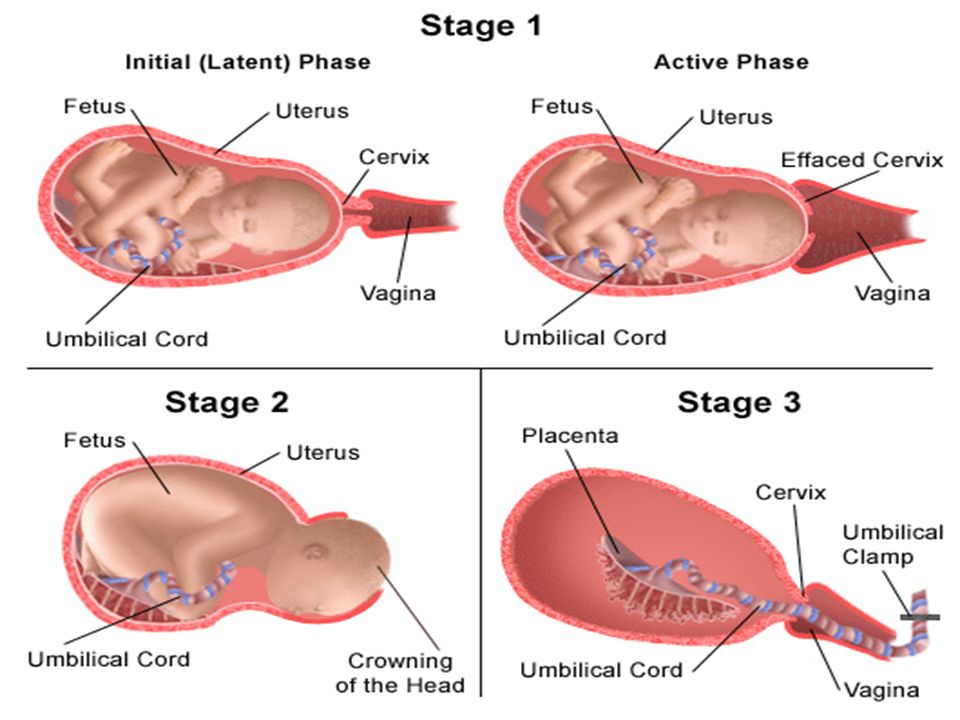

Samiyyah is 3 centimeters dilated, 100 percent effaced, and her water hasn't broken yet, which is common in the first stage of labor.

Birth centers offer a more relaxed and intimate alternative to hospitals for women expecting uncomplicated births.

It's important to choose a birth center with nearby hospital privileges in case of an emergency.

Helping her through her first natural birth is her husband, Arvan. Her mother-in-law, Irena, and 6-year-old son Safi are there for support.

Samiyyah: We've talked about, you know, what he's gonna see, we've shown him pictures, and I think he'll be okay.

Narrator: As Samiyyah's labor progresses, her baby's heart rate is monitored every 15 minutes.

Samiyyah: My goal is to remain calm and try to stay level-headed.

Narrator: As her contractions pick up, she starts experiencing painful back labor, typically caused by the baby's head pressing against the lower spine.

Samiyyah finds some relief by trying a combination of slow steady breathing, constant deep massaging and counterpressure, spending lots of time in a heated Jacuzzi, and trying different labor positions.

Arvan: She's doing great. She's doing great. She's really pushing through.

Narrator: Her midwife feels it's time to break her water with an amni hook, since she can feel the amniotic sac bulging. This is a common procedure and usually helps speed up the labor process.

Samiyyah: I thought it would be painful, but it wasn't at all. Actually it was like a relief of pressure.

Midwife Julia Rasch: Large amount of clear fluid. Beautiful.

Narrator: Her contractions now intensify as she starts to feel the urge to push. This is called hard labor or transition. The muscles your body uses to contract are transitioning from dilating the cervix to pushing the baby down and out._c53bbd6a-f309-45f6-b20e-2eb8914f5c67-eeeb18.jpg)

Midwife: The intensity of the contractions is increasing, and just a certain force is now really behind that baby coming.

Narrator: Transition can be the most painful part of labor -- but usually the shortest phase.

Narrator: Though most mothers dilate nearly 8 to 10 centimeters before transitioning, Samiyyah is only 5 centimeters dilated and is having trouble resisting the urge to push.

Arvan: Sam, do not push. Fight it. Fight it.

Samiyyah: I'm trying!

Narrator: Her midwife agrees her body is ready to deliver. Pushing before being fully dilated is uncommon. This is why each caregiver has to manage her patient's labor on an individual basis.

Midwife: Okay now, take a breath and do it again.

Narrator: Her midwife uses her fingers to pull back her cervical opening as Samiyyah pushes.

The midwife made the right decision, listening to her body. With just 11 minutes of pushing, Arvan and Samiyyah's baby emerges.

Samiyyah: [screams]

Arvan: Good job! Good job!

Midwife: There's your baby!

Narrator: Sami Sarrajj, a healthy boy, is placed immediately on his mother's chest.

Midwife: You did it! You did it!

Narrator: Dad cuts the umbilical cord, and the midwife collects some of the cord blood for routine testing.

It's not over yet. The midwife helps deliver the placenta, and a nurse presses on the fundus -- the upper part of the uterus -- to check how much the uterus has contracted.

Applying pressure is a common practice used by caregivers to help expel excess blood.

Samiyyah tore along her previous episiotomy line, and her midwife repairs it with stitches, which takes 15 minutes to complete.

Arvan: You did a hell of a job... Yeah!

Narrator: Samiyyah is now breastfeeding and bonding with her baby. Incredibly, in an hour, she is showered up and savoring some well-deserved fettucini Alfredo.

It was a fast delivery, with just four hours and 11 minutes of labor. Samiyyah's natural birth is a success, and she's ready to try it again.

Samiyyah: One more. We're going to try for a girl. (laughs)

Narrator: Everyone played a supportive part on the birth team… Even big brother Safi got to announce the news that his brother was born.

Live birth: Water birth | Video

Narrator: We women love our tub time, and Mary is no exception. As a labor and delivery nurse, she's seen the best and worst of birth. For her, warm water is the ultimate pain reliever during labor.

Mary: I want to use the water to help me cope naturally with the contractions or the surges and to help me deliver the baby in a more calm environment.

Mary and Dean tried water birth for the first time with their daughter Aubrey's delivery. The experience was so positive they're headed to the tub again for the birth of their fourth child.

Mary: I will have two by land and hopefully two by sea.

Midwife Karen Shields: Baby's head is right here. Perfect position for labor, which is great.

Mary: Good girl!

Midwife: A water birth is my favorite way to catch a baby.

Narrator: Karen Shields, Mary's midwife, has delivered over 200 babies in the water.

Midwife: Everything has to be going terrifically for the baby to be born in water, as you know.

The baby's heartbeat has to be what we call reactive, which means that the baby's, when the baby moves, the heart rate goes up. And there's no areas where the baby's heart rate is going down and that your blood pressure's normal and everything's good.

Narrator: You should not attempt a water delivery if you have high-risk prenatal issues such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or preeclampsia; you plan to use any pain medication; or your labor will be induced.

While laboring in a warm tub has become more acceptable as a way to cope with pain during labor, actual underwater birth is still unconventional and considered risky. It's not recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

If you're considering a water birth, talk to your caregiver about the risks and benefits.

It's important to decide in advance what tub you'll be delivering in. You can use your bathtub if it's big enough, but most women either buy or rent a special birthing tub. Ask your midwife what she recommends.

Ask your midwife what she recommends.

Mary will be using a tub at the New Jersey Hospital System -- Elmer that's specifically designed for water birth. This tub keeps the water warm and has three access points for getting in and out in case of an emergency.

After a long wait, Mary's labor kicks in ten days after her due date. It's 9:30 p.m., and her water hasn't yet broken.

Midwife: You're about 80 percent thinned out.

Mary: Yes, we got our 80, girls.

Narrator: Mary is using HypnoBirthing techniques, dim lights, and soothing music to stay relaxed and get through her labor. After four and a half hours, Mary has progressed to 7 centimeters. The birthing tub is prepped.

The midwife breaks her water with an amni hook. This is done before entering the tub to make sure the amniotic fluid is clear and free of meconium.

The safe and comfortable water temperature for mother and baby is between 98 and 101 degrees.

While Mary's in the tub, she moves into the transition stage of labor. This is the most intense part of labor, but the water seems to be helping.

This is the most intense part of labor, but the water seems to be helping.

Midwife: It helps her mobility. It helps prevent tearing. It helps the mother's blood pressure be lower. And just really gives her an overall feeling of comfort and relaxation.

Narrator: The baby's heart rate is monitored underwater. It's hard to believe Mary is just minutes away from giving birth.

The mood is calm and peaceful, and Mary gently rocks her hips as she focuses on her baby descending into the birth canal.

Mary gets in position to deliver. Two nurses hold her legs back as the baby's head begins to crown.

Midwife: OK, I want a big push this time.

Narrator: With the next push, the baby's head is visible.

The midwife quickly lifts the umbilical cord, which has wrapped around the baby's neck during delivery and makes her appear bluish.

While she's underwater, the baby is receiving all her oxygen through the umbilical cord.

The midwife holds the baby's head for the final push.

Midwife: Here we go…

Narrator: Mary and Dean's baby daughter Ashlind is born.

In seconds, she's brought to the surface.

Midwife: Hi, beautiful. Let's float her a little.

I think the reason I like water birth so much is the baby's reaction. They come out so calm and relaxed. Their whole body just unwinds, and you can see the stress just leave them.

Narrator: Parents often wonder why a baby born underwater doesn't swallow the water or, even worse, drown. [Midwife] Karen Shields believes babies have an innate ability to avoid this.

Midwife: There's what's called the natural dive reflex in babies, and that is so they don't take a breath underwater.

The stimulus for a baby to breathe is atmosphere or air on the cheek. That is what makes the baby take that initial breath.

Narrator: The umbilical cord reacts to the air as well.

Midwife: Until the cord comes up and is actually hit by the air, that's when the cord constricts and the blood flow is stopped to the baby.

Narrator: In two minutes, Ashlind, covered in vernix, is breathing on her own, and Dad cuts her cord.

Mary gave birth to a healthy 8 pound, 15 ounce baby.

The water birth was everything she hoped it would be.

The vision of a newborn child

Newborn children see in a completely different way than adults. FROM as the child grows, his visual system also develops, for the final it takes about 8 months to form.

Eyes the child is able to see immediately after birth, but his brain, which processes and forms visual images until it is able to correctly decrypt information. The child grows, his brain develops, and at the same time and visual abilities. How does this happen?

1 month. At that age the child's eyes cannot move in concert. The pupils often converge on bridge of the nose, but parents should not panic that this is strabismus. Already to at the end of 1 month of life, the baby learns to fix his gaze on the interesting object.

2 months. Starts actively develop color vision. Shades are faintly distinguishable, but good perceived contrasting colors. Children of this age love bright toys and keep a good eye on them.

4 months. Appears spatial perception, the child begins to understand that objects have different shapes and can be located at different distances from it. Coordination the movements of the newborn are being improved, now he can easily pick up, subject of interest to him.

5 months. Improving color perception, the child is able to see the difference in shades, even in small sized items.

8 months. Visual the abilities of a toddler of this age are indistinguishable from those of an adult person. By 8 months, as a rule, the final color of the rainbow is also formed. shells of the eyes, however, this process can be delayed up to 3 years.

Parents are advised to be attentive to visual abilities of your child and, in case of developmental disabilities, show him ophthalmologist. What to focus on:

What to focus on:

· At 3-4 months, the baby is not able to follow the eyes behind moving objects.

· The eyes are inactive in both directions.

· The look is constantly running, the baby cannot fix it at one point.

· Eyes roll.

· The child is older than 1 month, and he continues strabismus persist.

· Frequent tearing.

· Fear of bright light.

· The pupil is white.

Watch your health the eye of a child from birth.

Why childbirth is so difficult and dangerous

- Colin Barras

- BBC Earth

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you sort things out.

Image copyright iStock

For a long time, scientists believed that the reason for such difficult childbirth in women is the upright posture of a person. However, recent research shows that this is not the only thing, says BBC Earth 9 columnist 0073 .

However, recent research shows that this is not the only thing, says BBC Earth 9 columnist 0073 .

The birth of a child is a long and painful process, and sometimes deadly. According to the World Health Organization, about 830 women die every day due to complications during pregnancy and childbirth (which, however, is 44% lower than in 1990).

"These statistics are astounding," says Jonathan Wells of University College London, who studies infant nutrition. "Female mammals have never had to pay such a high price for offspring."

- Russian woman who gave birth to 69 children: truth or fiction?

- Pregnancy and childbirth in the UK: free and without a doctor

- Can you determine the sex of the baby by the size of the mother's belly?

- "Age is one day": the first hours of a new life

But why is childbirth so dangerous for women? And what can we do to reduce the death rate?

Scientists first began to think about the causes of such dramatic childbirth in women in the middle of the 20th century. They quickly, as it seemed then, found an explanation.

They quickly, as it seemed then, found an explanation.

Problems with childbearing began in the earliest members of our evolutionary lineage, the hominins, who diverged from other primates about seven million years ago.

These were animals that had little in common with us today, except, perhaps, for the fact that already in those distant times, like us, they walked on two legs.

Photo copyright JUAN MANUEL BORRERO/naturepl.com

Photo captionHominins have been moving upright for millions of years

Walking upright caused the hominin skeleton to change - it stretched out, and this affected the shape of the pelvis.

In most primates, the birth canal is relatively straight. Among the hominins, they soon changed quite markedly. The hips became narrower, and the birth canal curved.

Thus, at the dawn of our history, hominin babies had to twist and turn in order to squeeze through the birth canal. This made the birth process very difficult.

This made the birth process very difficult.

But things soon got worse.

About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to change again. They lost their ape-like features and became more like modern humans.

Their bodies have become a little longer, their arms have become shorter, and their brains have noticeably enlarged. And this last detail was bad news especially for women.

Image copyright, Science Photo Library

Image caption,About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to lose their ape-like features and become more like modern humans

It seems that evolution has begun to contradict itself. On the one hand, the pelvis of women had to narrow so that they could move on two legs, on the other hand, the babies they carried had an enlarged head, complicating the process of passing through the already narrow birth canal.

Childbirth has become an incredibly painful and potentially dangerous business, which it has remained to this day.

In 1960, the anthropologist Sherwood Washburn called this theory the "obstetrical dilemma" and this explanation satisfied many scientists. But not everyone.

Holly Dunsworth of the University of Rhode Island was initially fascinated by Washburn's theory, but later realized that a lot of it didn't add up.

According to Washburn, when the human brain expanded two million years ago, the woman's body began to adapt to this, and the duration of pregnancy was noticeably reduced.

Photo credit, Science Photo Library/Alamy

Photo caption,Many women use pain relief during childbirth

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

And it seems like a pretty logical hypothesis: babies started being born at an earlier stage of development, and anyone who has ever seen a newborn baby will attest to how helpless and vulnerable he is.

However, Dunsworth believes that this is simply not true.

"Our babies are born fairly large, and female pregnancies last 37 days longer than monkeys of the same size," explains the researcher.

The same applies to the size of the brain. Females give birth to babies with larger heads than females of other primates, with about the same body weight as females. And this means that the key points of Washburn's hypothesis are false.

And that's not all. The central assumption of the obstetrical dilemma is that the size and shape of the human pelvis, in particular in women, has changed greatly due to our habit of walking in an upright position.

However, if evolution were to solve the problem of childbirth in humans, it would certainly have already made women's hips and, accordingly, the birth canal a little wider.

Our ability to walk on two legs would not be affected at all.

Photo credit, Visuals Unlimited/naturepl. com

com

Men's (left) and women's (right) pelvises

In 2015, researchers from Harvard University conducted an experiment that involved men and women with different body types.

The researchers observed the physical activity of volunteers in the lab and found that those with wider hips had no problem walking or running.

So, if nature, through evolution, made women's hips a little wider and thus facilitated childbearing, women's ability to move would not deteriorate.

According to Dunsworth, the duration of pregnancy in women is not determined by the size of the baby's brain, as the obstetric dilemma suggests.

The fact is that a woman's body is simply not able to feed a fetus that requires too much energy for longer than 39-40 weeks.

This means that the reason for this length of pregnancy is not the difficulty of passing the child through the birth canal, as Washburn believed.

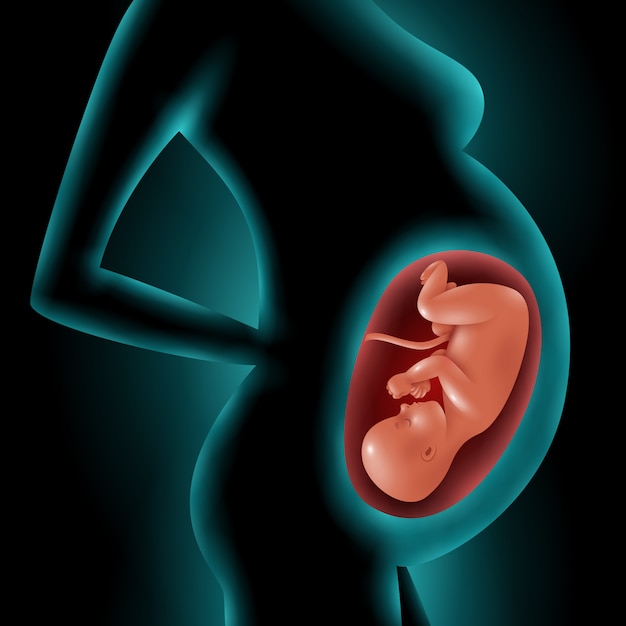

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Fetus on CT scan

What then is the true cause of difficult labor in women? In 2012, researcher Jonathan Wells of University College London and his team began to study the history of childbirth and came to a startling conclusion.

For most of human evolution, it was obviously much easier to have a baby than it is now.

From the little evidence that remains to this day, it follows that in early hunter-gatherer societies, childbirth was one of the smallest problems.

Archaeologists find almost no skeletons of babies from this period, which indicates a relatively low mortality rate in early childhood.

But the situation changed dramatically a few thousand years ago, when people switched to a sedentary lifestyle.

Many more newborn bones appear in the archaeological record from the early agricultural era.

Photo copyright, Volker Steger/4 million years of man/SPL

Photo caption,Homo erectus, the immediate ancestor of modern humans, could have had a much easier birth process…

On the one hand, living in a more populous community led to outbreak of infectious diseases, and newborns, as the most vulnerable, became their victims.

On the other hand, the diet of farmers with a high content of carbohydrates began to differ markedly from the diet of hunter-gatherers, which was dominated by proteins.

This provoked changes in the body structure: as evidenced by archaeological finds, farmers were significantly shorter than hunter-gatherers.

And scientists who study childbirth are well aware that the shape and size of a woman's pelvis directly depends on her height.

The smaller the woman, the narrower her hips - hence, the transition to agriculture has complicated the process of childbearing.

On the other hand, a carbohydrate-rich diet has made babies gain weight faster in the womb, and it is much more difficult to give birth to a large baby.

Photo copyright, Jose Antonio Penas/Science Photo Library

Photo caption,Farming has once again changed our bodies

Thus, about 10 thousand years ago, childbirth, which for millions of years was a relatively easy process for humans, suddenly become a problem.

However, according to Holly Dunsworth, this is not the end of the story.

Scientific evidence shows that a woman's pelvis is at its best for childbirth around the age of 20, when she is at her peak fertility, and stays that way until about 40 years of age.

After that, it gradually changes its shape, preparing for menopause, and becomes less suitable for the birth of a child.

The question arises: if so many evolutionary factors influenced the characteristics of childbirth, maybe this process continues to this day?

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Pregnancy is sometimes debilitating for a woman

In December 2016, scientists Fischer and Mittereker published a sensational paper on this topic.

Previous studies have suggested that larger babies are more likely to survive, and that infant size at birth is to some extent a hereditary factor.

The growth of a medium-sized fetus is evolutionarily limited by the width of the female pelvis.