Anti d antibody pregnancy

Rhesus disease - Diagnosis - NHS

Rhesus disease is usually diagnosed during the routine antenatal checks and tests you're offered during pregnancy.

Blood tests

A blood test should be carried out early on in your pregnancy to test for conditions such as iron deficiency anaemia, rubella (german measles), HIV and AIDS and hepatitis B.

Your blood will also be tested to determine which blood group you are, and whether your blood is rhesus (RhD) positive or negative (see causes of rhesus disease for more information).

If you're RhD negative, your blood will be checked for the antibodies (known as anti-D antibodies) that destroy RhD positive red blood cells. You may have become exposed to them during pregnancy if your baby has RhD positive blood.

If no antibodies are found, your blood will be checked again at 28 weeks of pregnancy and you'll be offered an injection of a medication called anti-D immunoglobulin to reduce the risk of your baby developing rhesus disease (see preventing rhesus disease for more information).

If anti-D antibodies are detected in your blood during pregnancy, there's a risk that your unborn baby will be affected by rhesus disease. For this reason, you and your baby will be monitored more frequently than usual during your pregnancy.

In some cases, a blood test to check the father's blood type may be offered if you have RhD negative blood. This is because your baby won't be at risk of rhesus disease if both the mother and father have RhD negative blood.

Checking your baby's blood type

It's possible to determine if an unborn baby is RhD positive or RhD negative by taking a simple blood test during pregnancy.

Genetic information (DNA) from the unborn baby can be found in the mother's blood, which allows the blood group of the unborn baby to be checked without any risk. It's usually possible to get a reliable result from this test after 11 to 12 weeks of pregnancy, which is long before the baby is at risk from the antibodies.

If your baby is RhD negative, they're not at risk of rhesus disease and no extra monitoring or treatment will be necessary. If they're found to be RhD positive, the pregnancy will be monitored more closely so that any problems that may occur can be treated quickly.

In the future, RhD negative women who haven't developed anti-D antibodies may be offered this test routinely, to see if they're carrying an RhD positive or RhD negative baby, to avoid unnecessary treatment.

Monitoring during pregnancy

If your baby is at risk of developing rhesus disease, they'll be monitored by measuring the blood flow in their brain. If your baby is affected, their blood may be thinner and flow more quickly. This can be measured using an ultrasound scan called a Doppler ultrasound.

If a Doppler ultrasound shows your baby's blood is flowing faster than normal, a procedure called foetal blood sampling (FBS) can be used to check whether your baby is anaemic (iron deficiency anaemia).

This procedure involves inserting a needle through your abdomen (tummy) to remove a small sample of blood from your baby. The procedure is performed under local anaesthetic, usually on an outpatient basis, so you can go home on the same day.

There's a small (usually 1 to 3%) chance that this procedure could cause you to lose your pregnancy, so it should only be carried out if necessary.

If your baby is found to be anaemic, they can be given a transfusion of blood through the same needle. This is known as an intrauterine transfusion (IUT) and it may require an overnight stay in hospital.

FBS and IUT are only carried out in specialist units, so you may need to be referred to a different hospital to the one where you are planning to have your baby.

Read more about treating rhesus disease.

Diagnosis in a newborn baby

If you're RhD negative, blood will be taken from your baby's umbilical cord when they're born. This is to check their blood group and see if the anti-D antibodies have been passed into their blood. This is called a Coombs test.

This is to check their blood group and see if the anti-D antibodies have been passed into their blood. This is called a Coombs test.

If you're known to have anti-D antibodies, your baby's blood will also be tested for iron deficiency anaemia and newborn jaundice.

Page last reviewed: 16 November 2021

Next review due: 16 November 2024

Rhesus disease - Prevention - NHS

Rhesus disease can largely be prevented by having an injection of a medication called anti-D immunoglobulin.

This can help to avoid a process known as sensitisation, which is when a woman with RhD negative blood is exposed to RhD positive blood and develops an immune response to it.

Blood is known as RhD positive when it has a molecule called the RhD antigen on the surface of the red blood cells.

Read more about the causes of rhesus disease.

Anti-D immunoglobulin

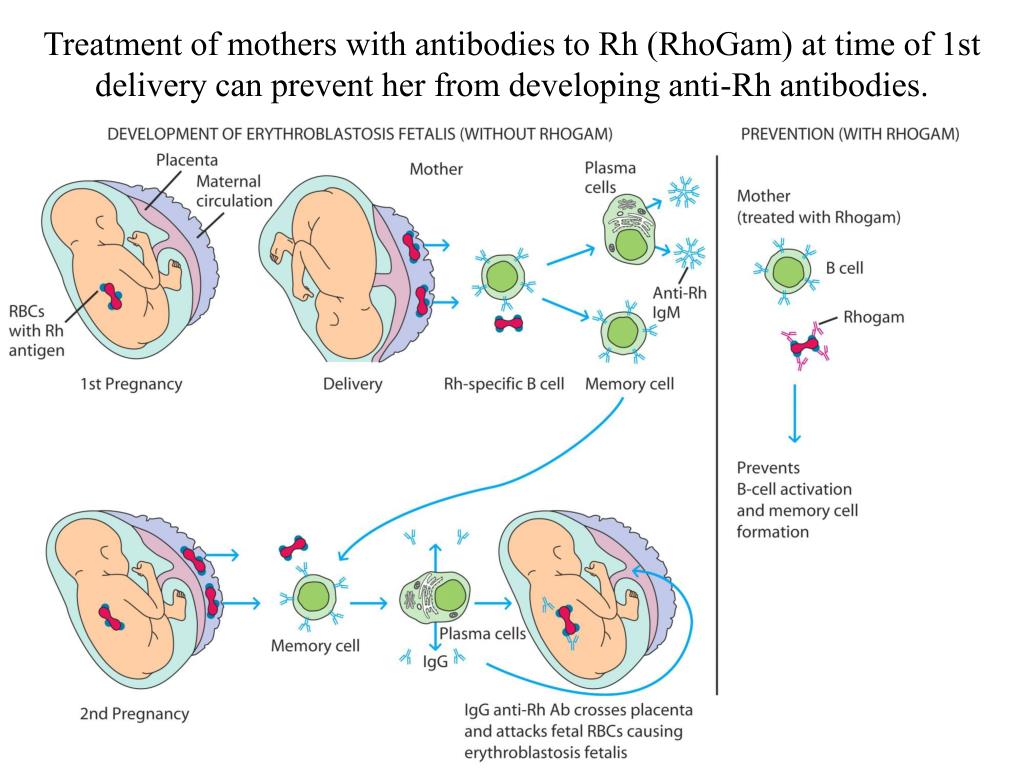

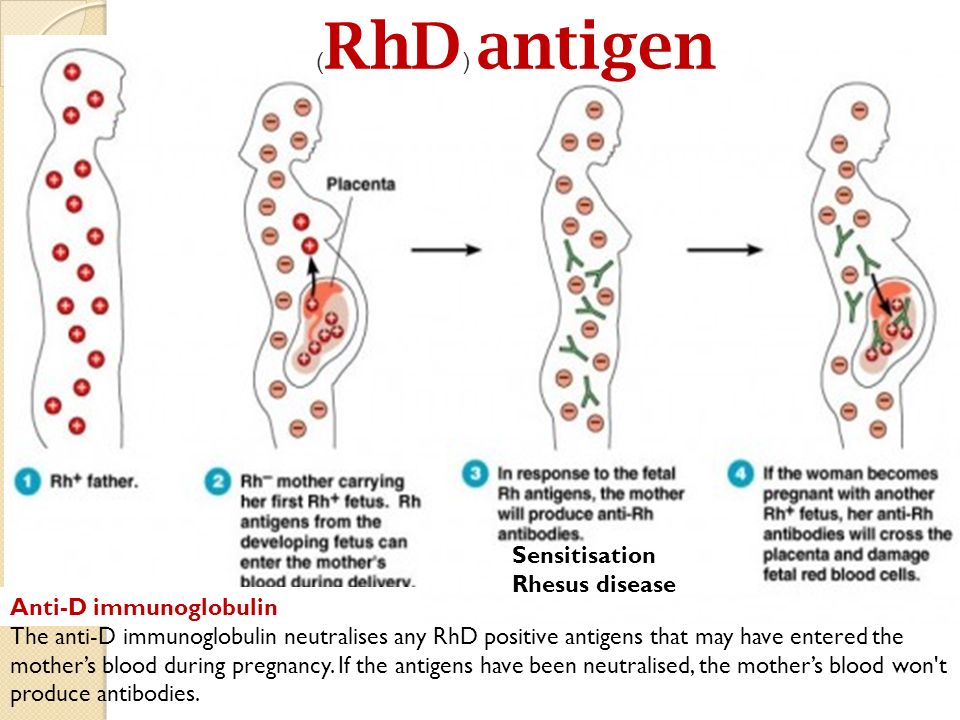

The anti-D immunoglobulin neutralises any RhD positive antigens that may have entered the mother's blood during pregnancy. If the antigens have been neutralised, the mother's blood won't produce antibodies.

You'll be offered anti-D immunoglobulin if it's thought there's a risk that RhD antigens from your baby have entered your blood – for example, if you experience any bleeding, if you have an invasive procedure (such as amniocentesis), or if you experience any abdominal injury.

Anti-D immunoglobulin is also administered routinely during the third trimester of your pregnancy if your blood type is RhD negative. This is because it's likely that small amounts of blood from your baby will pass into your blood during this time.

This routine administration of anti-D immunoglobulin is called routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis, or RAADP (prophylaxis means a step taken to prevent something from happening).

Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis (RAADP)

The 2 ways you can receive RAADP are a:

- 2-dose treatment: where you receive 2 injections; 1 during the 28th week of your pregnancy and the other during the 34th week

- 1-dose treatment: where you receive an injection of immunoglobulin at some point during weeks 28 to 30 of your pregnancy

There doesn't seem to be any difference in the effectiveness between the 1-dose or 2-dose treatments. Your local integrated care board (ICB) may prefer to use a 1-dose treatment, because it can be more efficient in terms of resources and time.

When will RAADP be given?

RAADP is recommended for all pregnant RhD negative women who haven't been sensitised to the RhD antigen, even if you previously had an injection of anti-D immunoglobulin.

As RAADP doesn't offer lifelong protection against rhesus disease, it will be offered every time you become pregnant if you meet these criteria.

RAADP won't work if you've already been sensitised. In these cases, you'll be closely monitored so treatment can begin as soon as possible if problems develop.

Anti-D immunoglobulin after birth

After giving birth, a sample of your baby's blood will be taken from the umbilical cord. If you're RhD negative and your baby is RhD positive, and you haven't already been sensitised, you'll be offered an injection of anti-D immunoglobulin within 72 hours of giving birth.

The injection will destroy any RhD positive blood cells that may have crossed over into your bloodstream during the delivery. This means your blood won't have a chance to produce antibodies and will significantly decrease the risk of your next baby having rhesus disease.

Complications from anti-D immunoglobulin

Some women are known to develop a slight short-term allergic reaction to anti-D immunoglobulin, which can include a rash or flu-like symptoms.

Although the anti-D immunoglobulin, which is made from donor plasma, will be carefully screened, there's a very small risk that an infection could be transferred through the injection.

However, the evidence in support of RAADP shows that the benefits of preventing sensitisation far outweigh these small risks.

Page last reviewed: 16 November 2021

Next review due: 16 November 2024

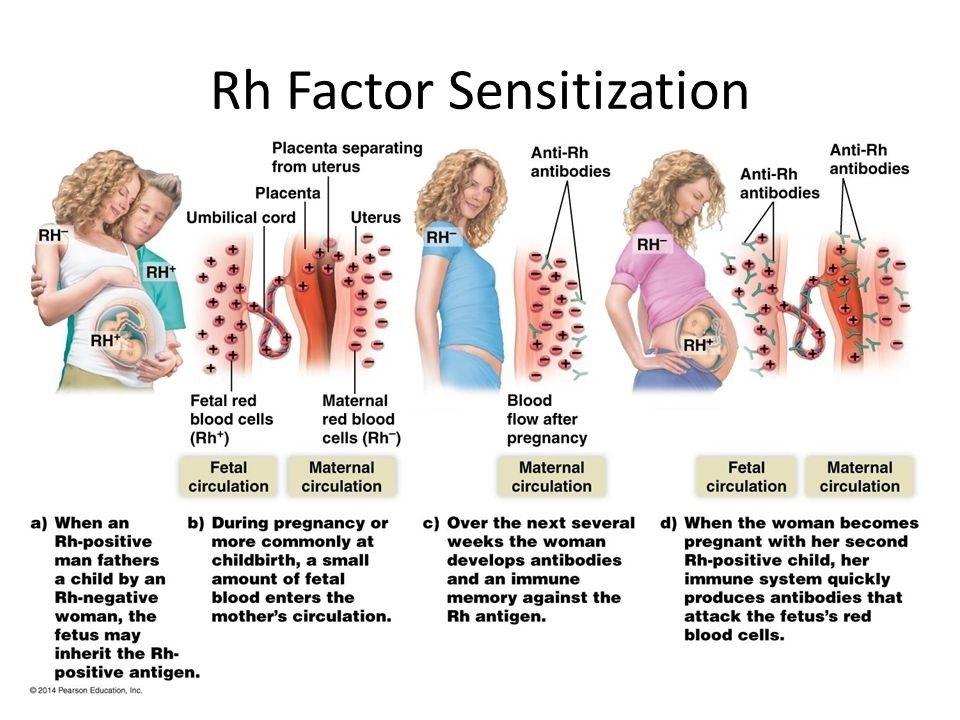

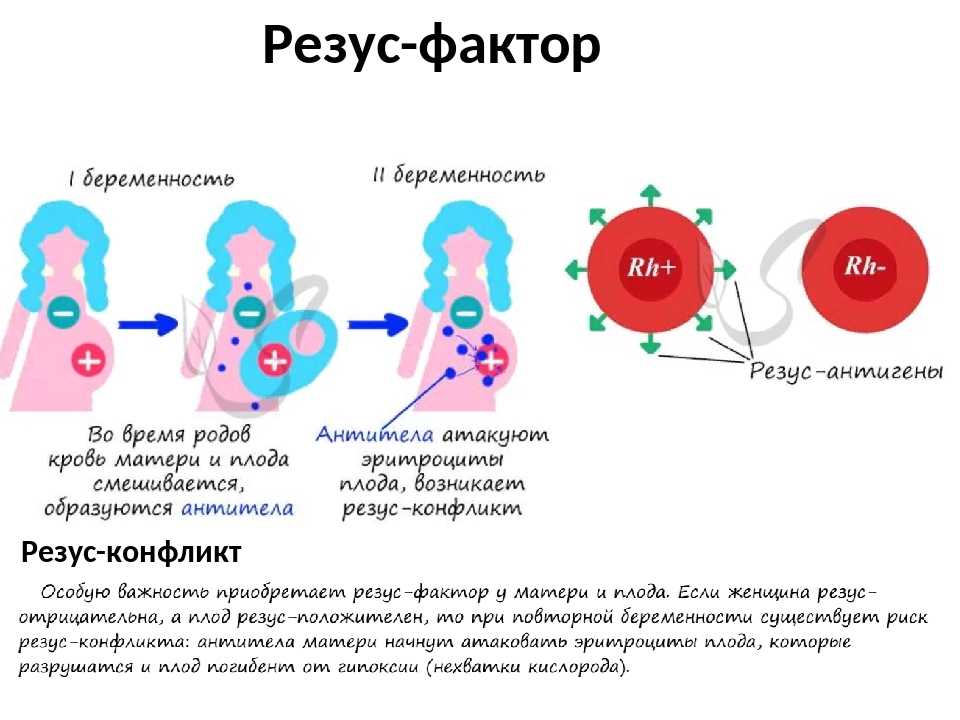

Pregnancy and Rh

All parents dream of having a healthy baby. Many risks associated with the health of the baby are now manageable. This means that some, even very serious and dangerous diseases are preventable, the main thing is not to waste time. For example, the situation associated with the development of hemolytic disease in the fetus and newborn. Many have heard that in the presence of Rh-negative blood in the mother, it is possible to develop an immunological conflict between the mother and the fetus in the Rh system, which later causes a severe hemolytic disease, from which the baby may already suffer in utero, but few can explain in detail what is it, and what to do if it directly concerns you.

For example, the situation associated with the development of hemolytic disease in the fetus and newborn. Many have heard that in the presence of Rh-negative blood in the mother, it is possible to develop an immunological conflict between the mother and the fetus in the Rh system, which later causes a severe hemolytic disease, from which the baby may already suffer in utero, but few can explain in detail what is it, and what to do if it directly concerns you.

First, let's figure out what the Rh factor is.

Rh factor is a special complex of proteins (also called D-antigen) that is located on the surface of red blood cells. It can be determined by laboratory methods (blood test). Most people in the population have the D antigen. Such people are said to be Rh-positive. A minority of the population (about 15-18%) do not have D antigen in their blood cells; such people are called Rh-negative.

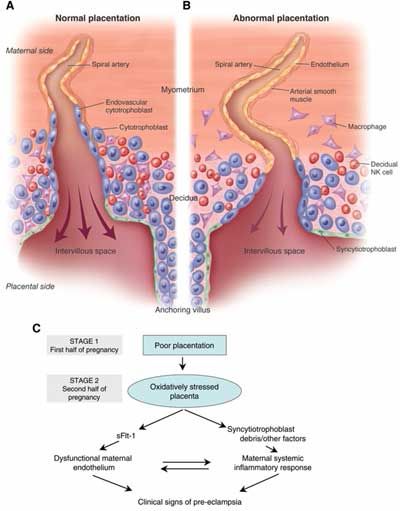

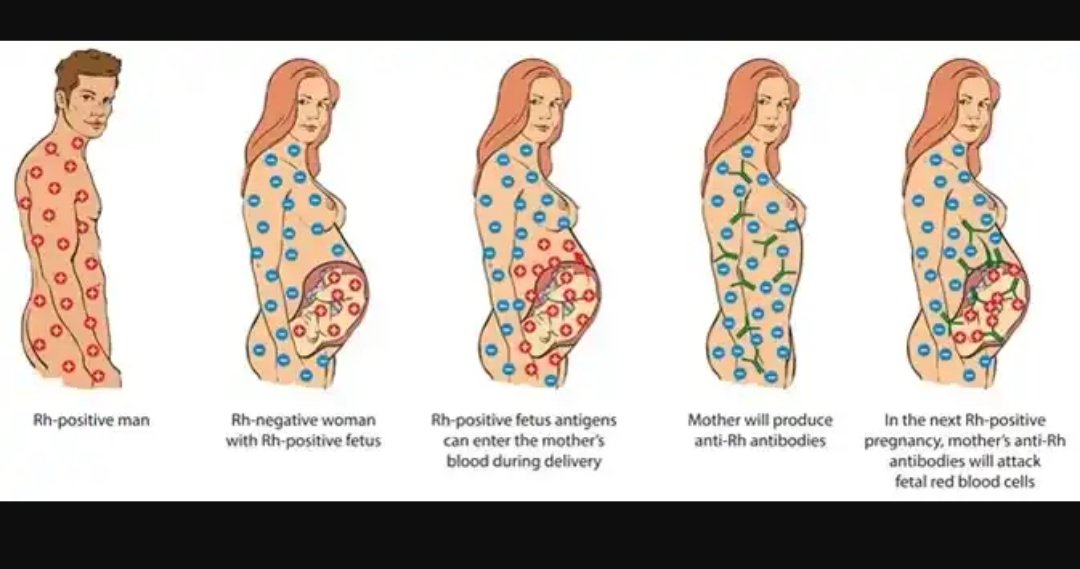

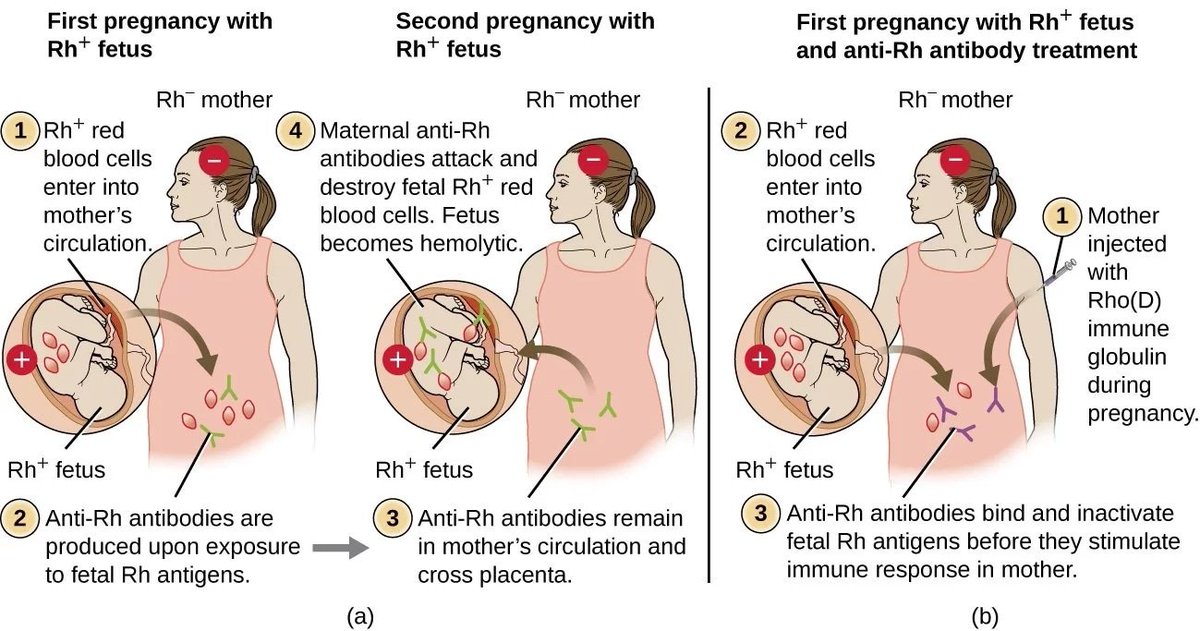

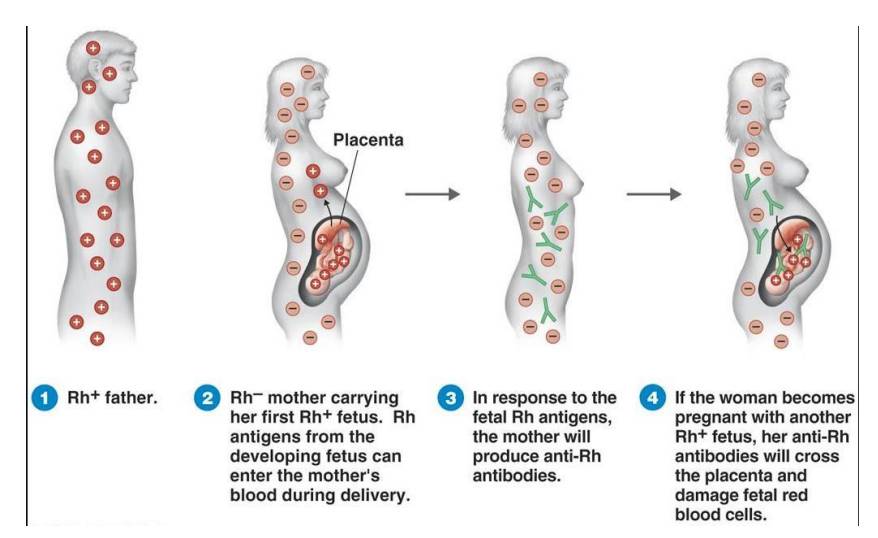

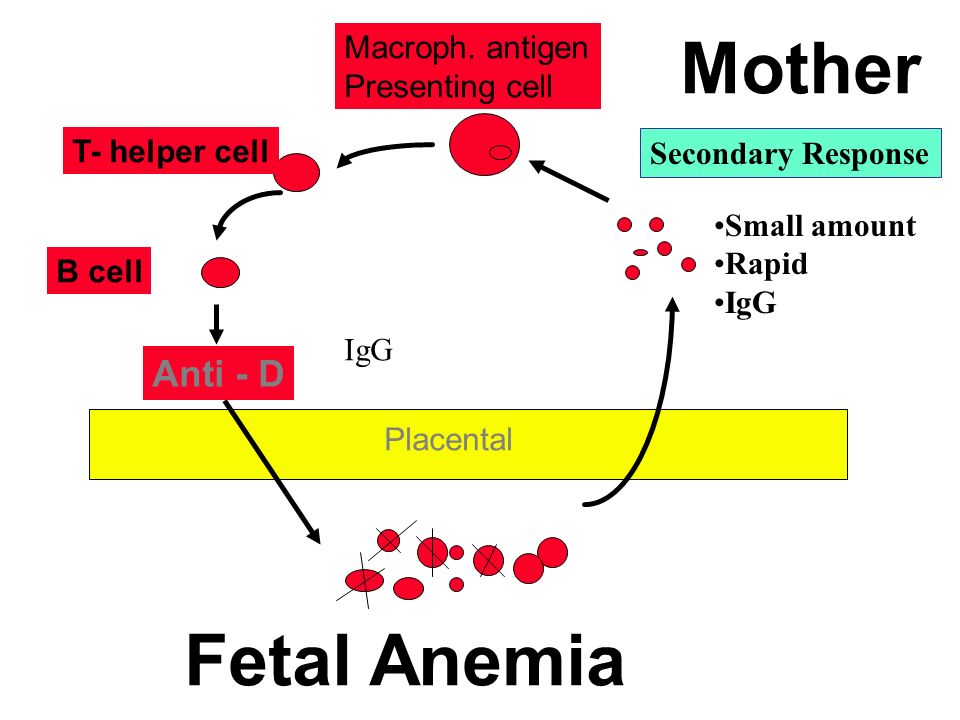

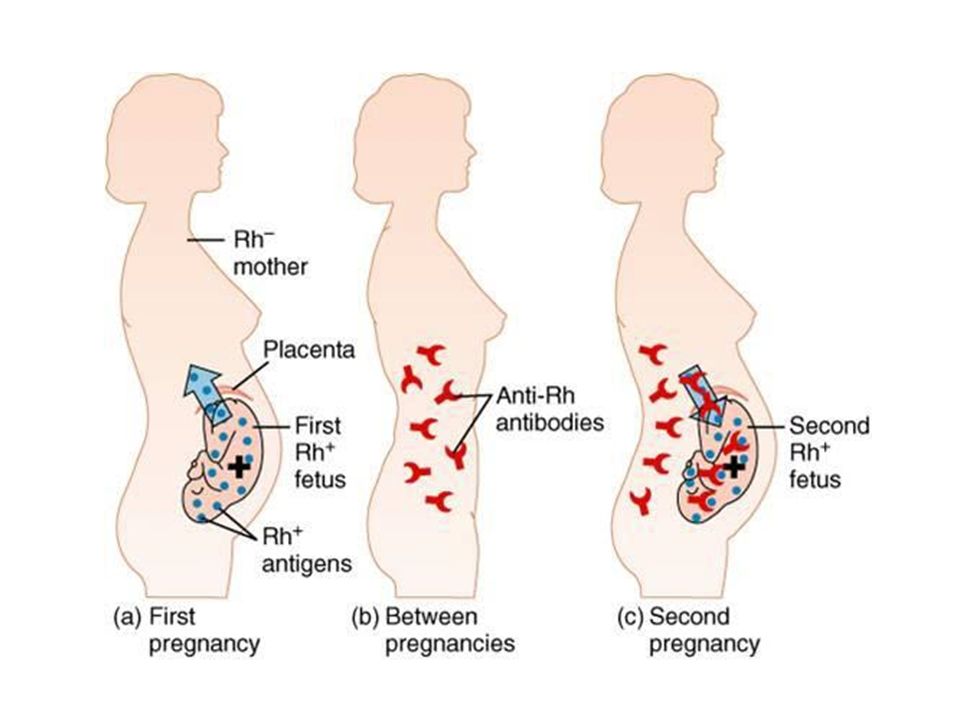

Rh factor is inherited, and a child can inherit it from both mother and father. If the mother is Rh-negative and the father is Rh-positive, there is a high chance that the child will inherit the father's Rh-positive father. Then it turns out that the mother does not have the D-antigen in the blood, but the fetus has it. The mother's immune system can perceive the fetal erythrocytes penetrating into her blood as foreign, and begin to fight them by synthesizing antibodies. These antibodies have a very low molecular weight, are able to cross the placenta into the fetal circulation and destroy fetal red blood cells, causing hemolytic disease in the fetus. Such a pathological condition in which the synthesis of antibodies occurs is called Rh immunization.

If the mother is Rh-negative and the father is Rh-positive, there is a high chance that the child will inherit the father's Rh-positive father. Then it turns out that the mother does not have the D-antigen in the blood, but the fetus has it. The mother's immune system can perceive the fetal erythrocytes penetrating into her blood as foreign, and begin to fight them by synthesizing antibodies. These antibodies have a very low molecular weight, are able to cross the placenta into the fetal circulation and destroy fetal red blood cells, causing hemolytic disease in the fetus. Such a pathological condition in which the synthesis of antibodies occurs is called Rh immunization.

Why is Rh immunization dangerous?

The main role of erythrocytes is the transport of oxygen to the organs and tissues of the body. With the massive destruction of these cells, the organs of the fetus begin to experience oxygen starvation. But that's not all. With the breakdown of red blood cells, a special substance is released - bilirubin, which has a toxic effect on the heart, liver, nervous system of the fetus. Bilirubin turns the baby's skin yellow (“jaundice”). In severe cases, bilirubin, exerting its toxic effect on brain cells, causes irreversible consequences, up to severe disability and death of the baby.

Bilirubin turns the baby's skin yellow (“jaundice”). In severe cases, bilirubin, exerting its toxic effect on brain cells, causes irreversible consequences, up to severe disability and death of the baby.

The level of danger increases with each successive pregnancy. The mother’s immune system has the ability to “remember” foreign proteins (Rhesus antigen of the fetus) and, during repeated pregnancy, responds with an even faster and more massive release of antibodies that can very quickly penetrate the placenta into the baby’s bloodstream and lead to severe intrauterine suffering and even death of the baby even before birth.

The risk factors for an Rh negative woman are therefore:

- Previous birth of an Rh-positive child (unless a special drug, anti-Rhesus immunoglobulin, was administered after the birth)

- Past fetal deaths

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Miscarriages and abortions

- Transfusion of Rh-incompatible blood before pregnancy

The first pregnancy in an Rh-negative woman is usually uneventful. Therefore, there is a tendency to keep the first pregnancy, in no case interrupting it, unless there are serious medical indications for this.

Therefore, there is a tendency to keep the first pregnancy, in no case interrupting it, unless there are serious medical indications for this.

What to do?

Fortunately, it should be noted that worldwide the incidence of hemolytic disease of the fetus in newborns due to Rh conflict is decreasing. And this happens because the methods of Rh prophylaxis are widely introduced into practice, which is carried out for Rh-negative women during pregnancy and after the birth of a Rh-positive baby. Yes, as in the case of all diseases without exception, it is easier to prevent a problem than to treat the consequences of an already developed severe Rh conflict.

To date, the only (and effective) preventive method to prevent this pathology is the introduction of a special drug - anti-D-immunoglobulin.

Preventive vaccination is carried out twice - during pregnancy (antenatal prophylaxis) and immediately after childbirth (postpartum prophylaxis).

Let's dwell on this in more detail.

The antenatal prophylaxis step aims to protect an existing pregnancy.

If the pregnancy proceeds without complications (“everything goes according to plan”), the woman is given prophylactic administration of anti-D-immunoglobulin at 28-32 weeks of pregnancy. A specially set dose is introduced, which provides protection for the baby until the end of pregnancy. This is planned prenatal prophylaxis.

Emergency prenatal prophylaxis is carried out in the event of dangerous situations that greatly increase the risk of developing a Rh conflict. These situations include:

- Complications of pregnancy: miscarriage; threatened miscarriage with bloody discharge

- Abdominal injury during pregnancy (e.g. after a fall or car accident)

- Therapeutic and diagnostic interventions during pregnancy: amniocentesis, chorionic biopsy, cordocentesis

In these cases, additional administration of the drug may be required to protect the fetus.

Stage postpartum prophylaxis aims to protect your future pregnancy.

If the baby is found to be Rh-positive after delivery, the mother is given another injection of anti-D-immunoglobulin. The drug should be administered as soon as possible, no later than 72 hours after delivery. If the vaccination is given later, its effectiveness is reduced and you cannot be sure that you did everything that was necessary to protect your next baby.

Attention! Women should receive the same prophylaxis with anti-D-immunoglobulin if:

- a miscarriage occurred at 5-6 weeks of gestation or more

- an abortion was performed at 5-6 weeks of gestation or more

- an operation was performed for an ectopic pregnancy

pregnancy and your unborn child. The introduction of the drug must also be made in the first 72 hours.

The protective effect of anti-D-immunoglobulin lasts only up to 12 weeks, therefore, with each subsequent pregnancy, repeated prophylactic administration is necessary.

Don't worry if you are Rh negative. Follow all the doctor's instructions and you will have a healthy baby!

Kozlyakova Olga Vladimirovna,

Head of the Department of Obstetric Immunohematology MCT

Candidate of Medical Sciences

Pregnancy in women with Rh-09 negative blood

The issue of Rhesus conflict during pregnancy is one of the few in medicine, in which all the i's are dotted and not only diagnostic and treatment methods have been developed, but, most importantly, effective prevention.

The history of immunoprophylaxis of Rhesus conflict is a rare example of unconditional success in medicine. Indeed, after the introduction of a set of preventive measures, infant mortality from complications of the Rhesus conflict decreased from 46 to 1.6 per 100 thousand children - that is, almost 30 times.

What is Rh conflict, why does it occur and what can be done to minimize the risk of its occurrence?

The entire population of the planet, depending on the presence or absence on erythrocytes (red blood cells) of the protein, denoted by the letter "D", is divided respectively into Rh-positive and Rh-negative people. According to approximate data, about 15% of Europeans are Rh-negative. When pregnancy occurs in an Rh-negative woman from an Rh-positive man, the probability of having an Rh-positive child is 60%.

According to approximate data, about 15% of Europeans are Rh-negative. When pregnancy occurs in an Rh-negative woman from an Rh-positive man, the probability of having an Rh-positive child is 60%.

In this case, when fetal erythrocytes enter the mother's bloodstream, an immune reaction occurs, as a result of which fetal erythrocytes are damaged, anemia and a number of other serious complications occur.

During physiological pregnancy, fetal erythrocytes cross the placenta in the first trimester in 3% of women, in the second - in 15%, in the third - in 48%. In addition, massive casting occurs in childbirth, after termination of pregnancy (abortion, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole), invasive procedures (chorionic villus biopsy, amniocentesis), prenatal bleeding with a threat of termination of pregnancy.

The total risk of developing an Rh conflict in Rh-negative women pregnant with an Rh-positive fetus in the absence of prophylaxis is about 16%. In women who have undergone prophylaxis, this risk is reduced to 0.2%.

In women who have undergone prophylaxis, this risk is reduced to 0.2%.

And now the most interesting - what is this very prevention and what needs to be done to keep the situation under control.

All women who applied to a medical institution for pregnancy registration, as well as those who applied to terminate an unwanted pregnancy, are assigned an analysis to determine the blood type and Rh factor. Sexual partners of women who have a negative Rh are also recommended to undergo an examination to establish Rh-affiliation. If, by a happy coincidence, a man also has a negative Rh factor, then there is no risk of an Rh conflict and there is no point in conducting immunoprophylaxis.

Women with Rh-negative blood and Rh-positive partner's blood who wish to terminate an unwanted pregnancy are advised to give an injection of anti-Rh immunoglobulin within 72 hours after the termination. The mechanism of action of this drug is based on the fact that the injected antibodies bind the fetal erythrocytes that have entered the maternal circulation and prevent the development of an immune response.

Rh-negative women registered for pregnancy are prescribed a monthly blood test for anti-Rh antibodies. Thus, it is determined whether there was contact between the blood of the mother and the fetus, and whether the woman's immune system reacted to a foreign protein.

If by the 28th week there are no anti-Rh antibodies in the woman's blood, she is sent for prophylactic administration of anti-Rh immunoglobulin. This prophylaxis is carried out from 28 to 30 weeks of pregnancy. After that, the determination of anti-Rhesus antibodies in the mother's blood is not carried out.

If, according to the results of the examination, anti-Rhesus antibodies are detected in a woman before 28 weeks of pregnancy, she is sent for an in-depth examination to determine the severity of the Rh conflict, timely treatment and, if necessary, emergency delivery.

After the birth of an Rh-negative woman, the Rh factor is determined. And, if the baby is Rh-positive, within 72 hours after birth, the woman is also injected with anti-Rh immunoglobulin.

Other situations requiring prophylactic administration of anti-Rhesus immunoglobulin:

- miscarriage or non-progressive pregnancy;

- ectopic pregnancy;

- hydatidiform mole;

- prenatal haemorrhage with threatened miscarriage;

- invasive intrauterine interventions during pregnancy.

The only controversial issue at the moment is the determination of the Rh factor of the fetus during pregnancy. To do this, starting from the 10th week of pregnancy, a woman’s blood is taken, the genetic material of the fetus is isolated from it, and on the basis of a genetic study, the Rh affiliation of the unborn child is determined.

On the one hand, this study would allow 40% of Rh-negative women carrying an Rh-negative fetus to avoid monthly testing of anti-Rh antibodies and the introduction of anti-Rh immunoglobulin.

On the other hand, this research does not appear in the official order of the Ministry of Health, is not included in the CHI system and is carried out only on a paid basis.