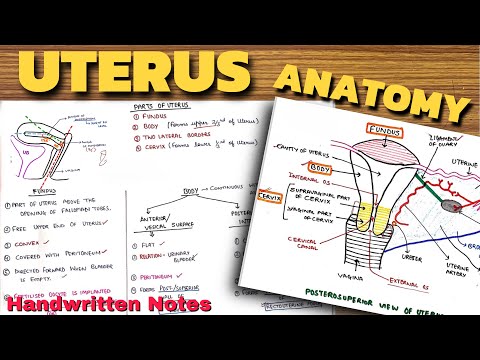

Anatomy uterine cervix

Anatomy of the uterine cervix and the transformation zone - Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer

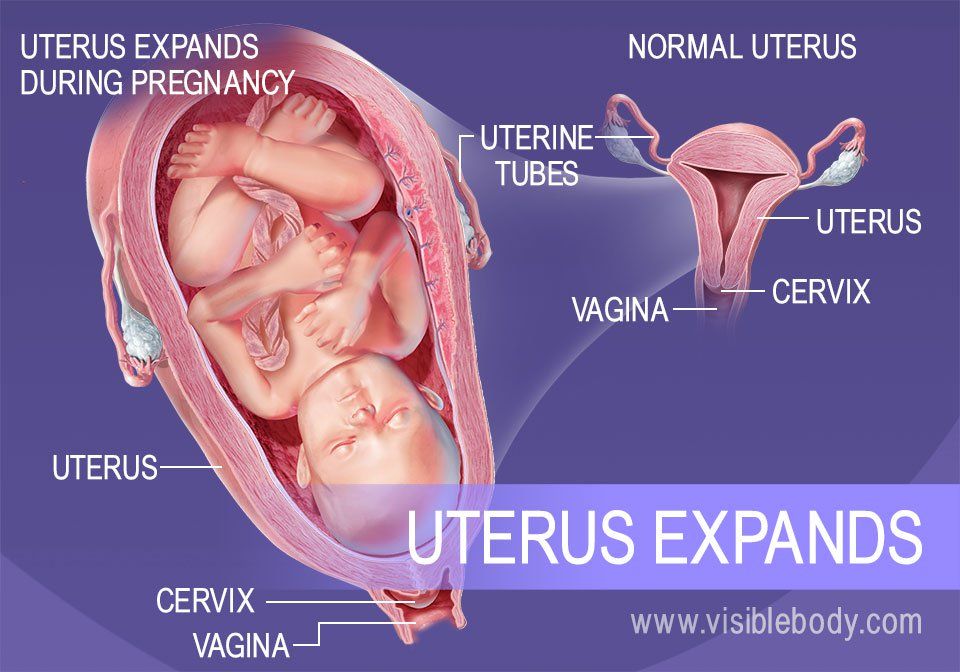

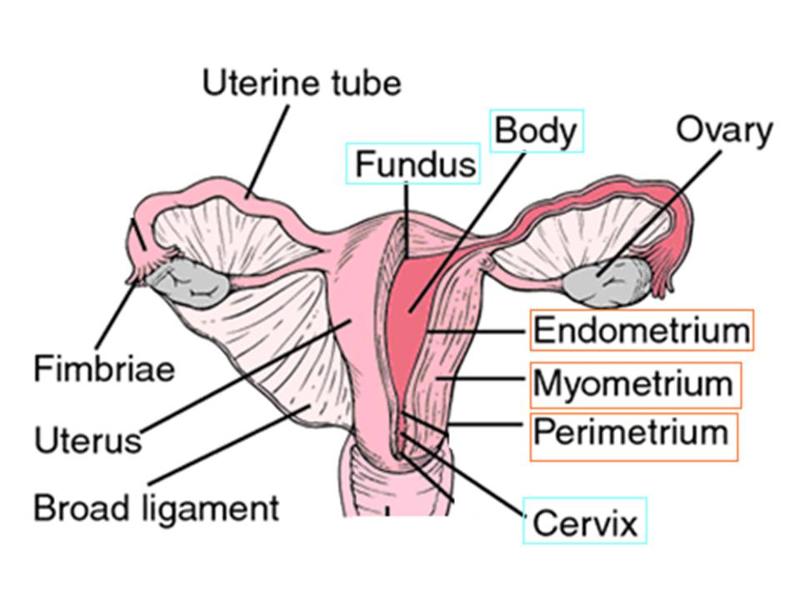

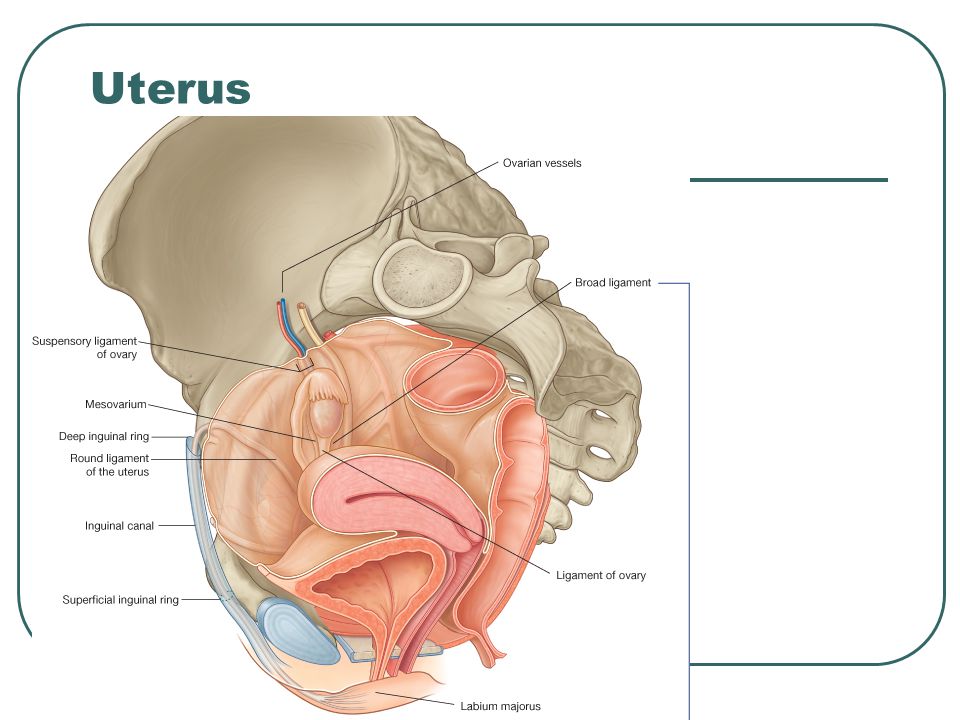

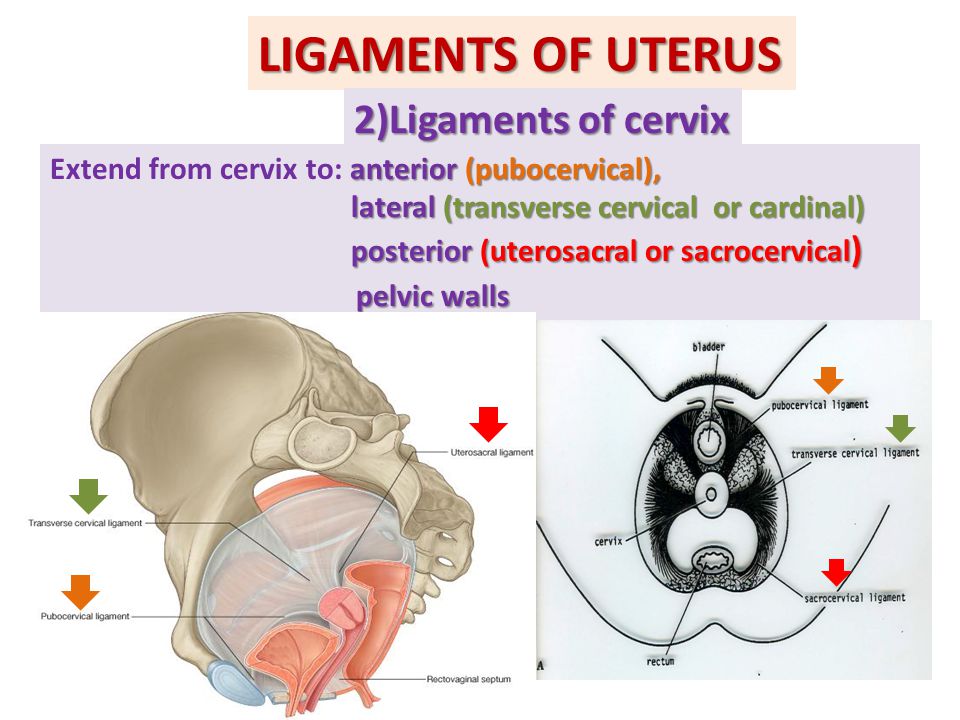

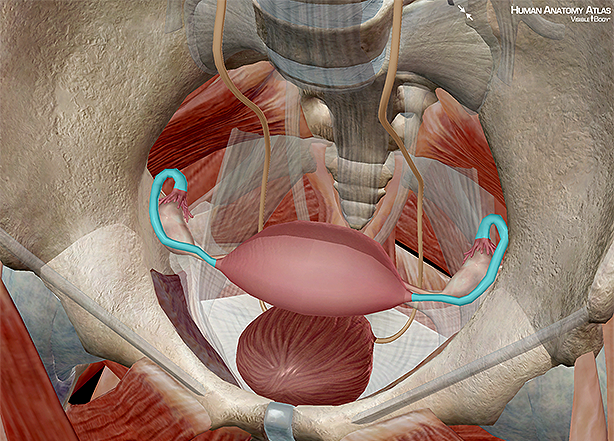

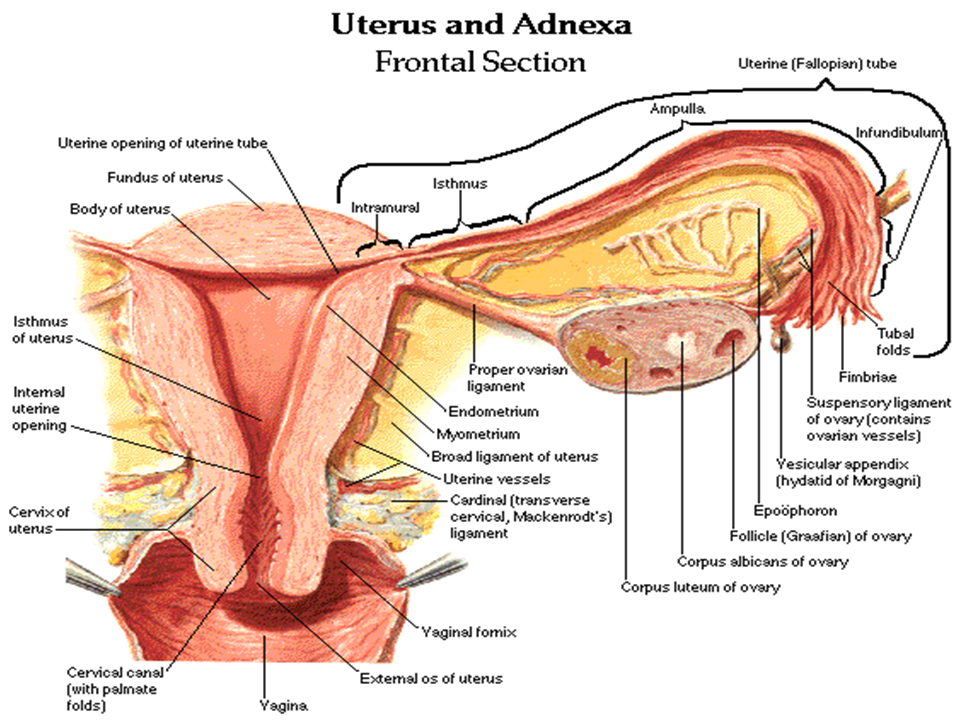

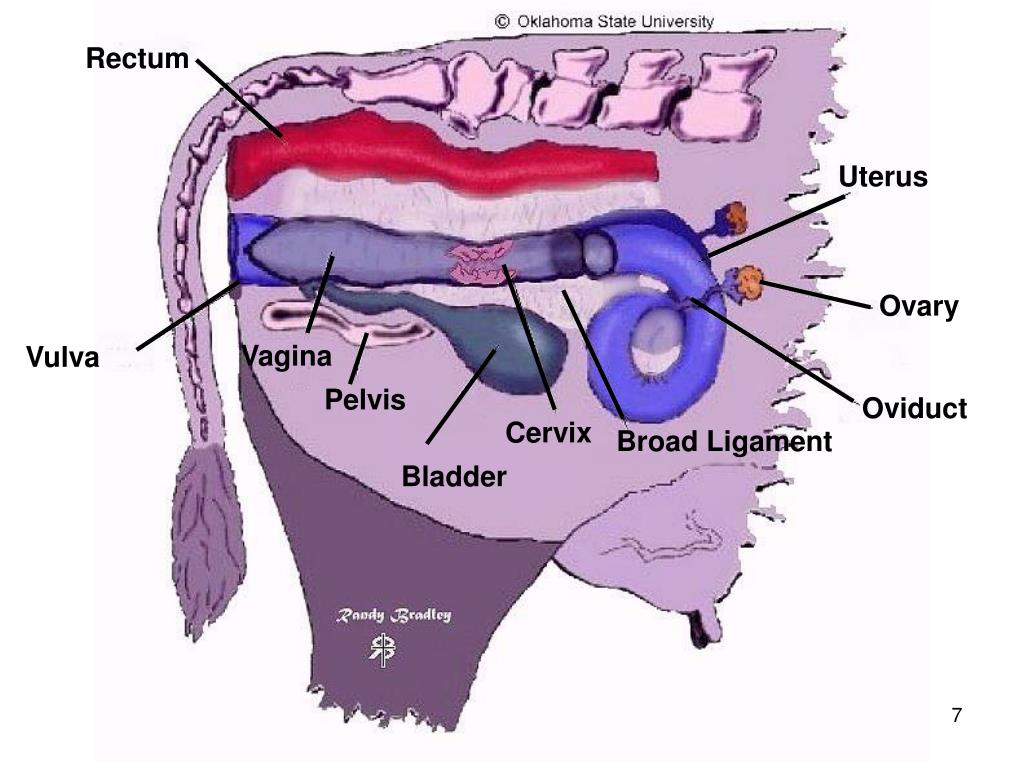

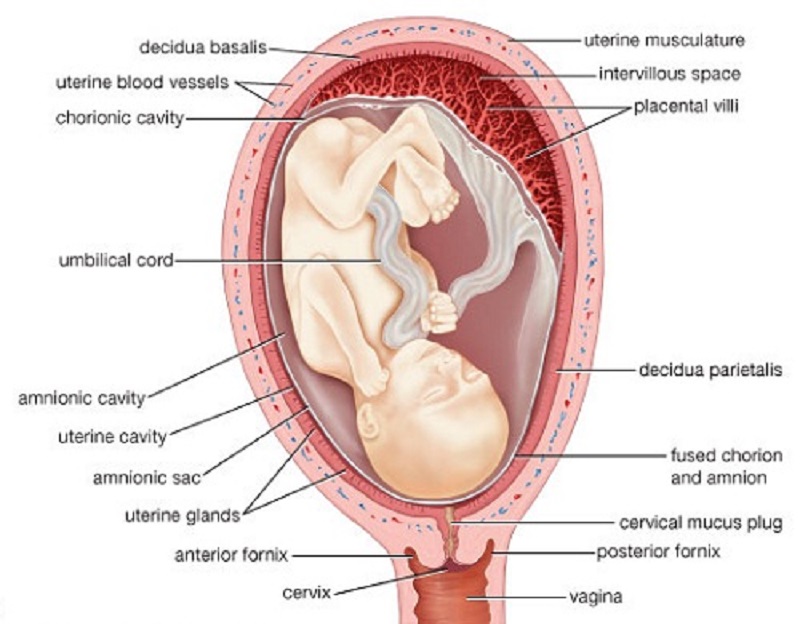

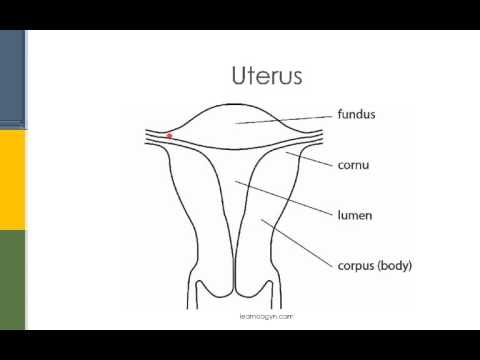

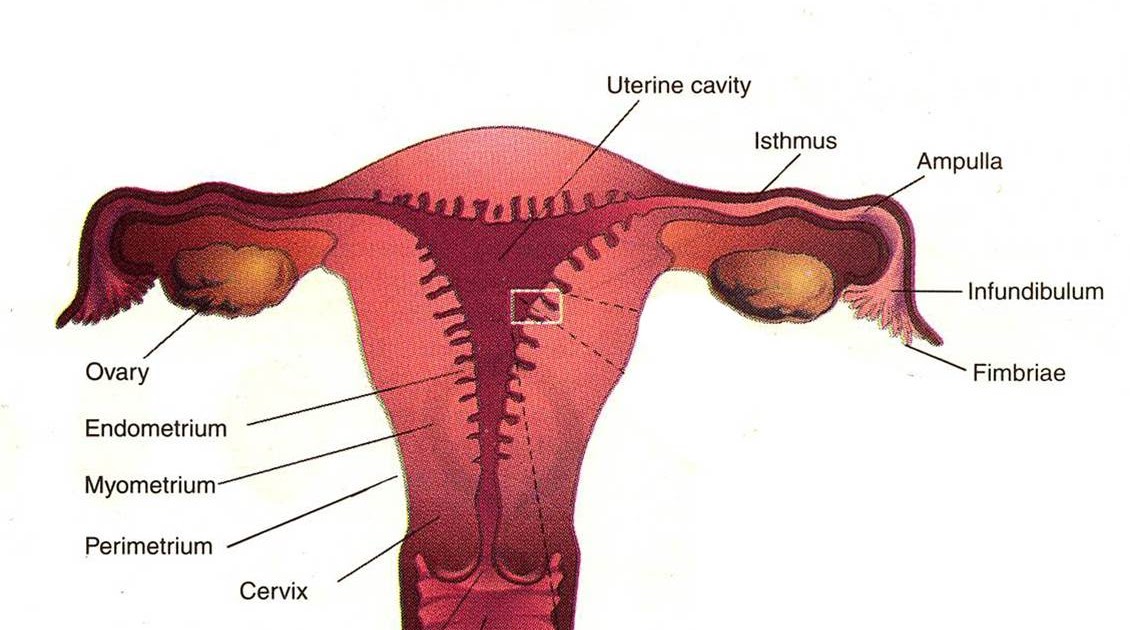

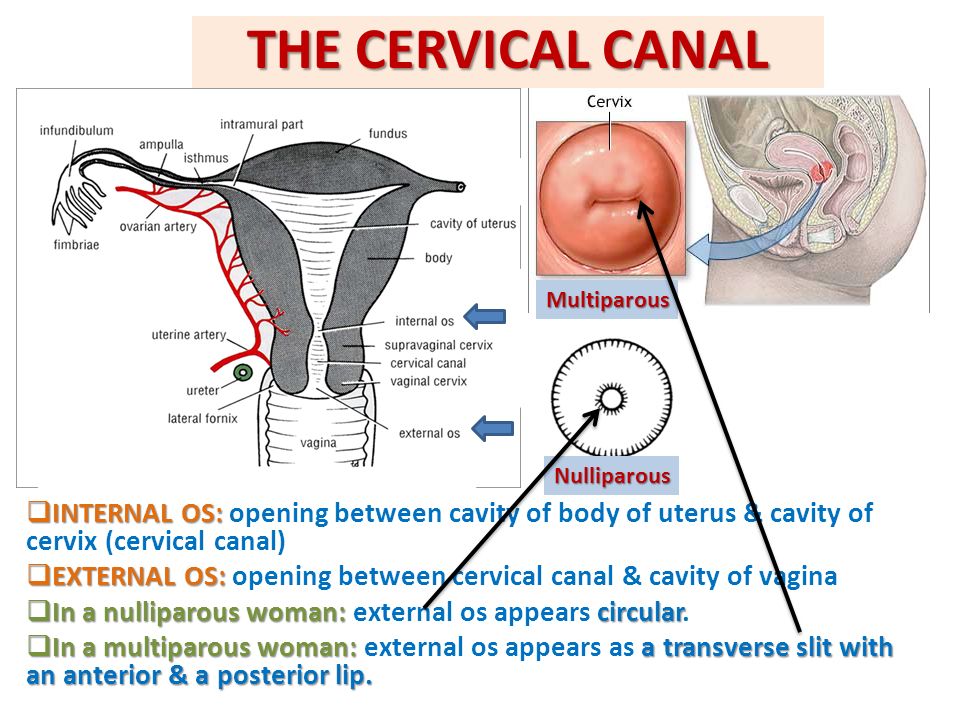

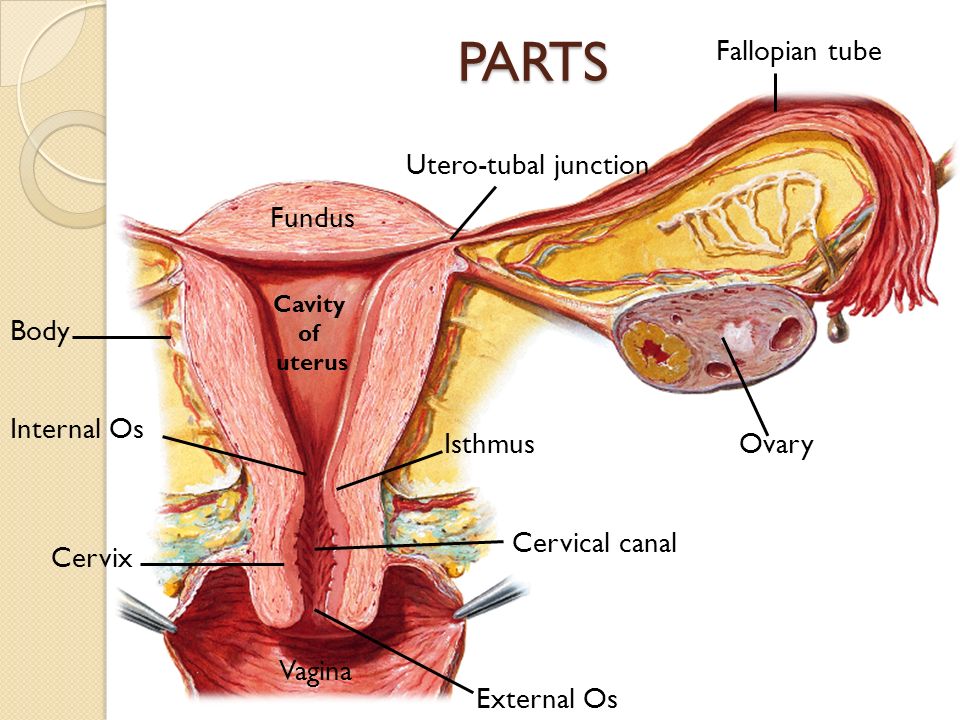

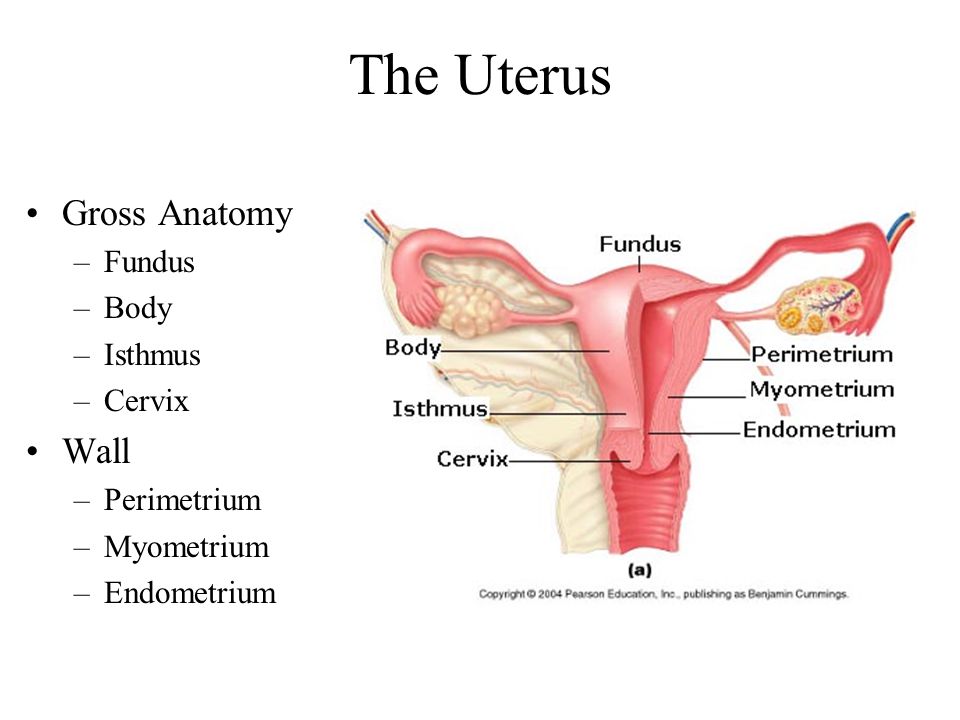

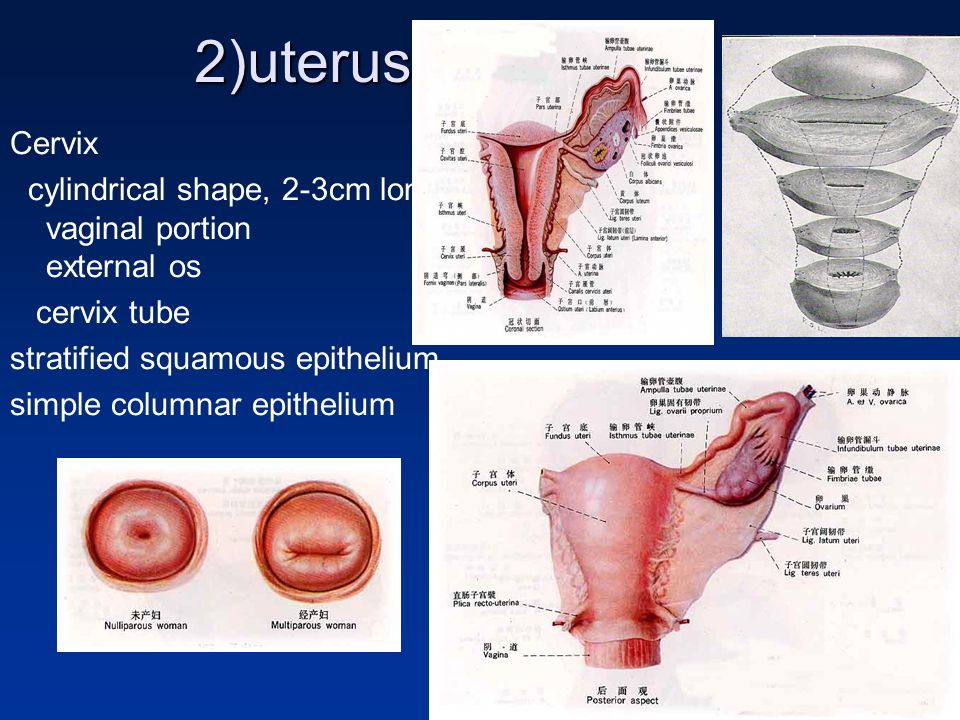

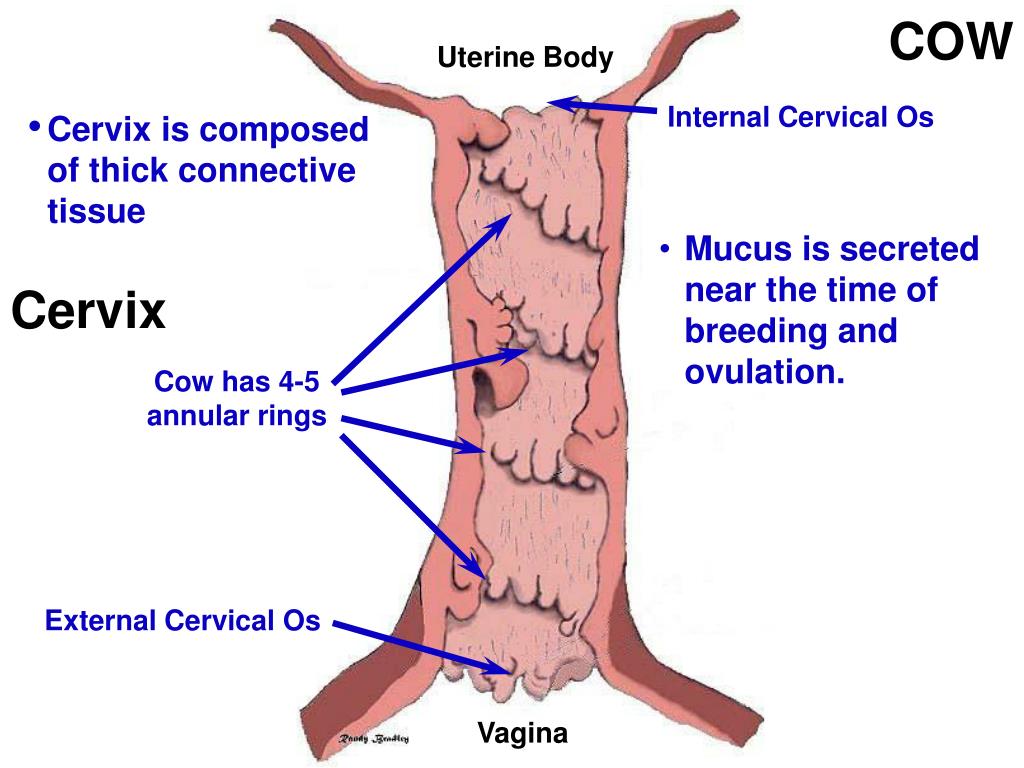

The cervix is a fibromuscular organ that links the uterine cavity to the vagina. Although it is described as being cylindrical in shape, the anterior and posterior walls are more often ordinarily apposed. The cervix is approximately 4 cm in length and 3 cm in diameter. The cervix of a parous woman is considerably larger than that of a nulliparous woman, and the cervix of a woman of reproductive age is considerably larger than that of a postmenopausal woman. The cervix occupies both an internal and an external position. Its lower half, or intravaginal part, lies at the upper end of the vagina, and its upper half lies above the vagina, in the pelvic/abdominal cavity (). The two parts are approximately equal in size. The cervix lies between the bladder anteriorly and the bowel posteriorly. Laterally, the ureters are in close proximity, as are the uterine arteries superiorly and laterally.

Fig. 2.1

Line drawing of normal female genital tract anatomy: sagittal section. In this drawing, the uterus is anteverted.

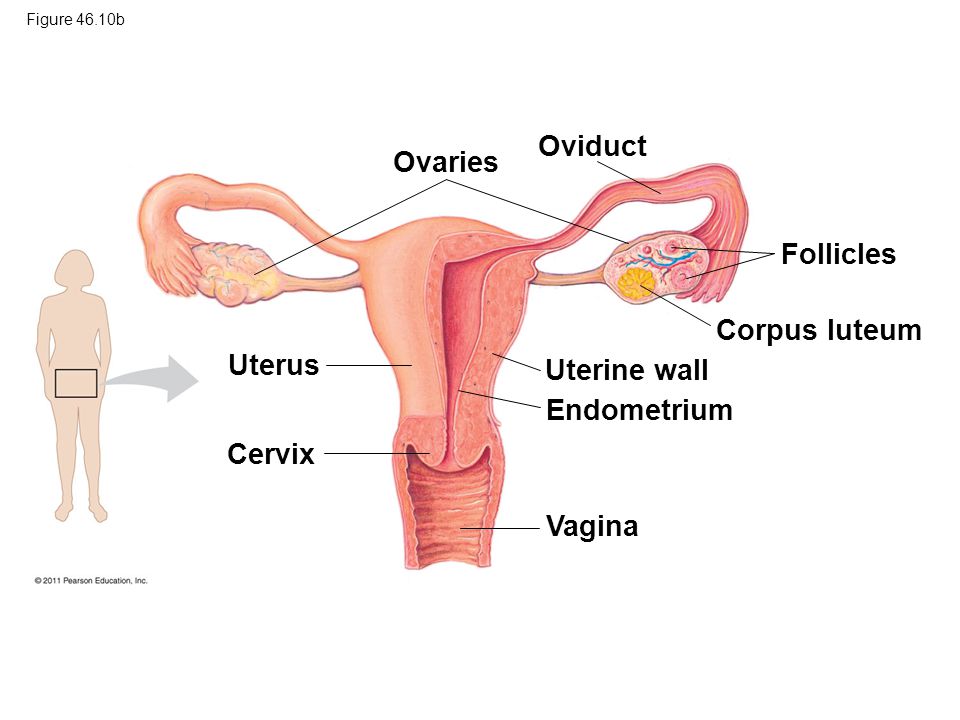

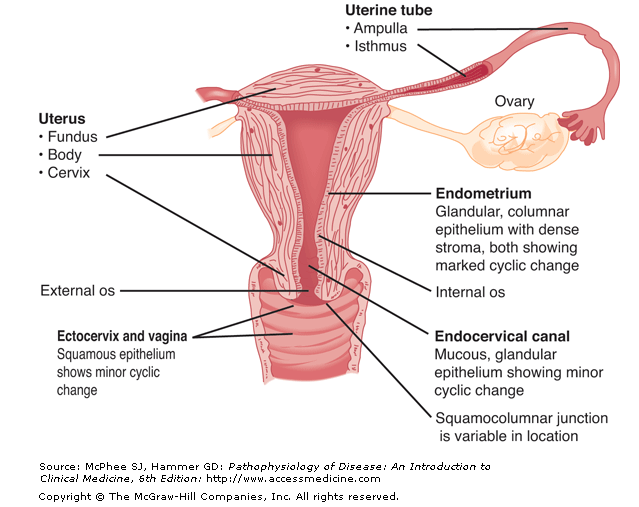

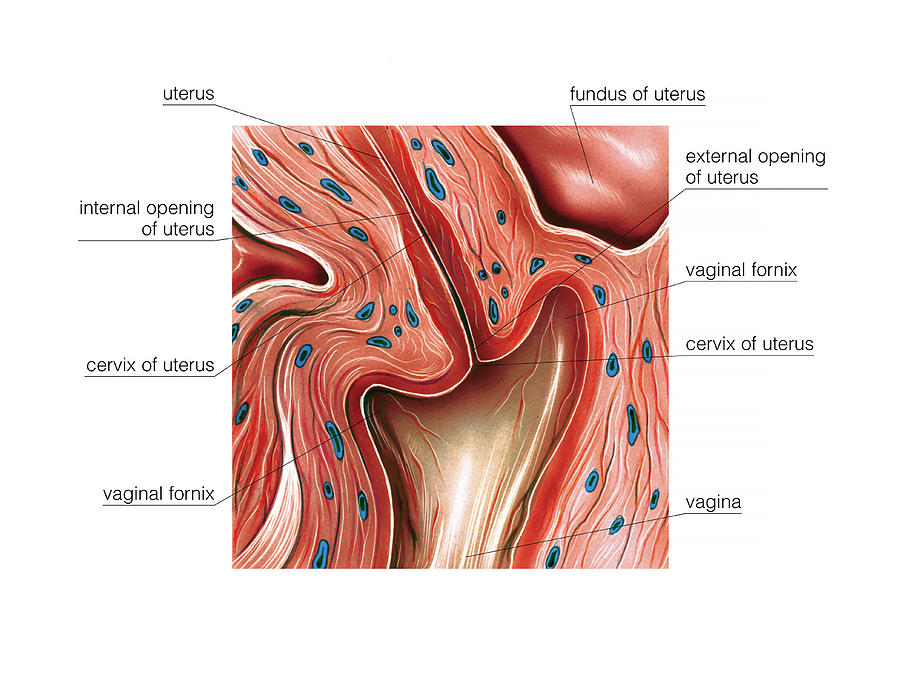

The cervix has several different linings. The endocervical canal is lined with glandular epithelium, and the ectocervix is lined with squamous epithelium. The squamous epithelium meets the glandular epithelium at the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ). The SCJ is dynamic and moves during early adolescence and during a first pregnancy. The original SCJ originates in the endocervical canal, but as the cervix everts during these times, the SCJ comes to lie on the ectocervix and becomes the new SCJ. In colposcopy terminology, the SCJ is this new SCJ. The epithelium between these two SCJs is the TZ or transition zone, and its position is also variable. It may be small or large and usually becomes more ectocervical during a woman’s reproductive years, returning to an endocervical position after menopause.

When the uterus is anteverted, the cervix enters the vaginal vault through a slightly posterior approach, whereby at speculum examination the cervical os is directed towards the posterior vaginal wall (). When the speculum is opened, the cervix tends to be brought more centrally into view and into line with the longitudinal axis of the vagina. Most women have an anteverted uterus. When the uterus is retroverted, the cervix tends to enter the vagina slightly more anteriorly, and in this case the cervix may be more difficult to locate at first speculum exposure. When the speculum is positioned properly and opened, the cervix tends to become positioned centrally and in a plane perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the vagina.

When the speculum is opened, the cervix tends to be brought more centrally into view and into line with the longitudinal axis of the vagina. Most women have an anteverted uterus. When the uterus is retroverted, the cervix tends to enter the vagina slightly more anteriorly, and in this case the cervix may be more difficult to locate at first speculum exposure. When the speculum is positioned properly and opened, the cervix tends to become positioned centrally and in a plane perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the vagina.

The external os of the cervix will nearly always be visible to the naked eye at speculum examination. The visible external lining of the cervix derives from the vaginal (squamous) epithelium. The endocervical or glandular epithelium is not usually visible to the naked eye at speculum examination. At the upper end of the cervical canal, the endocervical epithelium becomes the endometrial lining of the uterine cavity. The lower half, or intravaginal part, of the cervix lies at the top of the vagina, surrounded by the vaginal fornices. These are the lateral, anterior, and posterior fornices and are where the vaginal epithelium sweeps into the cervix circumferentially. Squamous cervical cancer accounts for the majority of cervical cancer and originates in the TZ. Glandular cervical cancer originates in either the TZ or the glandular epithelium above the TZ.

These are the lateral, anterior, and posterior fornices and are where the vaginal epithelium sweeps into the cervix circumferentially. Squamous cervical cancer accounts for the majority of cervical cancer and originates in the TZ. Glandular cervical cancer originates in either the TZ or the glandular epithelium above the TZ.

2.1. Tissue constituents of the cervix

2.1.1. Stroma

The stroma of the cervix is composed of dense, fibromuscular tissue through which vascular, lymphatic, and nerve supplies to the cervix pass and form a complex plexus.

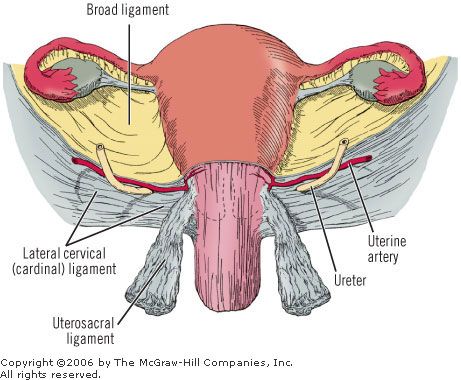

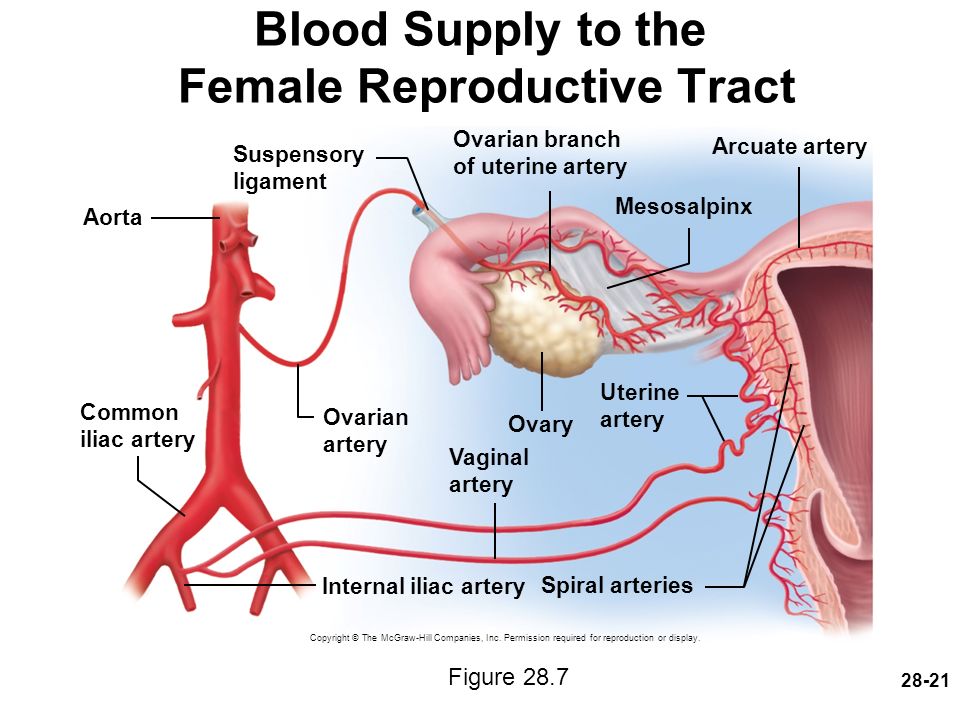

The arterial supply of the cervix is derived from the internal iliac arteries through the cervical and vaginal branches of the uterine arteries. The cervical branches of the uterine arteries descend in the lateral aspects of the cervix at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions. The veins of the cervix run parallel to the arteries and drain into the hypogastric venous plexus. The lymphatic vessels from the cervix drain into the common iliac, external iliac, internal iliac, obturator, and parametrial nodes.

The nerve supply to the cervix is derived from the hypogastric plexus. The endocervix has extensive sensory nerve endings, whereas there are very few in the ectocervix. Hence, procedures such as biopsy, thermal coagulation, and cryotherapy are relatively well tolerated in most women, although there is good evidence that local anaesthesia effectively prevents the discomfort of these procedures. Also, the cervix of a parous woman tends to have slightly less sensory appreciation, which may be due to damage to nerve endings during childbirth. Because sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres are also abundant in the endocervix, dilatation and/or curettage of the endocervix may occasionally lead to a vasovagal reaction.

The cervix is covered by both stratified, non-keratinizing squamous epithelium and columnar epithelium. As mentioned above, these two types of epithelium meet at the SCJ.

2.1.2. Squamous epithelium

Usually, most of the ectocervix and the entire length of the vagina is lined with squamous epithelium, which is uniform, stratified, and non-keratinizing. Because mature squamous epithelium contains glycogen, it readily takes up Lugol’s iodine (and is therefore Schiller test-negative). When epithelium does not take up Lugol’s iodine, it is Schiller test-positive. Cervical squamous epithelium is smooth and looks slightly pink to the naked eye in its non-pregnant state. During pregnancy it becomes progressively more vascular and develops a bluish hue.

Because mature squamous epithelium contains glycogen, it readily takes up Lugol’s iodine (and is therefore Schiller test-negative). When epithelium does not take up Lugol’s iodine, it is Schiller test-positive. Cervical squamous epithelium is smooth and looks slightly pink to the naked eye in its non-pregnant state. During pregnancy it becomes progressively more vascular and develops a bluish hue.

The lowest level of cells in the squamous epithelium is a single layer of round basal cells with large dark-staining nuclei and little cytoplasm, attached to the basement membrane (). The basement membrane separates the epithelium from the underlying stroma. The epithelial–stromal junction is usually straight. Sometimes it is slightly undulating, with short projections of stroma, which occur at regular intervals. These stromal projections are called papillae, and the parts of the epithelium between the papillae are called rete pegs.

Fig. 2.2

Squamous epithelium of the vagina and ectocervix.

The basal cells divide and mature to form the next few layers of cells, called parabasal cells, which also have relatively large dark-staining nuclei and greenish-blue basophilic cytoplasm. Further differentiation and maturation of these cells leads to the intermediate layers of polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm and small, round nuclei. These cells form a basket-weave pattern. With further maturation, the superficial layers of large and markedly flattened cells with small, dense, pyknotic nuclei and transparent cytoplasm are formed. Overall, from the basal layer to the superficial layer, these cells undergo an increase in size and a reduction in nuclear size.

The cells in the intermediate and superficial layers contain abundant glycogen in their cytoplasm, which stains mahogany brown or black after the application of Lugol’s iodine and magenta with periodic acid–Schiff stain in histological sections. Glycogenation of the intermediate and superficial layers is a sign of normal maturation and development of the squamous epithelium. Abnormal or altered maturation is characterized by a lack of glycogen production.

Abnormal or altered maturation is characterized by a lack of glycogen production.

The maturation of the squamous epithelium of the cervix is dependent on estrogen, and if estrogen is lacking, full maturation and glycogenation do not take place. Hence, after menopause, the cells do not mature beyond the parabasal layer and do not accumulate as multiple layers of flat cells. Consequently, the epithelium becomes thin and atrophic. On visual examination, it appears pale, sometimes with subepithelial petechial haemorrhagic spots, because it is easily prone to trauma.

2.1.3. Columnar epithelium

The endocervical canal is lined with columnar epithelium (often referred to as glandular epithelium). It is composed of a single layer of tall cells with dark-staining nuclei close to the basement membrane (). Because of its single layer of cells, it is much shorter in height than the stratified squamous epithelium of the cervix. On visual examination, it appears reddish, because the thin single-cell layer allows penetration of the stromal vascularity.![]() At its distal or upper limit, it merges with the endometrial epithelium in the lowest part of the body of the uterus. At its proximal or lower limit, it meets with the squamous epithelium at the SCJ. It covers a variable extent of the ectocervix, depending on the woman’s age and reproductive, hormonal, and menopausal status.

At its distal or upper limit, it merges with the endometrial epithelium in the lowest part of the body of the uterus. At its proximal or lower limit, it meets with the squamous epithelium at the SCJ. It covers a variable extent of the ectocervix, depending on the woman’s age and reproductive, hormonal, and menopausal status.

Fig. 2.3

Columnar epithelium of the endocervical canal.

The columnar epithelium does not form a flattened surface in the cervical canal but is thrown into multiple longitudinal folds protruding into the lumen of the canal, giving rise to papillary projections. It forms several invaginations into the substance of the cervical stroma, resulting in the formation of endocervical crypts (sometimes referred to as endocervical glands) (). The crypts may traverse as far as 5–6 mm from the surface of the cervix. This complex architecture, consisting of mucosal folds and crypts, gives the columnar epithelium a grainy or grape-like appearance on visual inspection.

Fig. 2.4

Endocervical crypts lined with columnar epithelium.

A localized overgrowth of the endocervical columnar epithelium may occasionally be visible as a reddish mass protruding through the external os on visual examination of the cervix. This is called a cervical polyp ( and ). It usually begins as a localized enlargement of a single columnar papilla and appears as a mass as it enlarges. It is composed of a core of endocervical stroma lined with columnar epithelium with underlying crypts. Occasionally, multiple polyps may arise from the columnar epithelium. The polyp shown in is lined with columnar epithelium, and it is protected from the metaplastic influence of the vaginal environment by endocervical mucus. The polyp shown in has undergone a degree of metaplasia so that it is partially covered by squamous epithelium.

Fig. 2.5

A cervical polyp in the endocervical canal. It is protected from the vaginal environment by abundant mucus in the canal. It is lined with columnar epithelium.

It is lined with columnar epithelium.

Fig. 2.6

A cervical polyp that has undergone a degree of metaplasia so that it is partially covered by squamous epithelium.

Glycogenation and mitoses are absent in the columnar epithelium. Because of the lack of intracellular cytoplasmic glycogen, the columnar epithelium does not change colour after the application of Lugol’s iodine or remains slightly discoloured with a thin film of iodine solution.

2.1.4. Squamocolumnar junction (SCJ)

The SCJ () sometimes appears as a sharp line with a step, because of the difference in the height of the squamous and columnar epithelium. The location of the SCJ in relation to the external os is variable over a woman’s lifetime and depends on factors such as age, hormonal status, birth trauma, use of oral contraceptives, and pregnancy.

Fig. 2.7

The squamocolumnar junction (SCJ).

The SCJ that is visible during childhood, during perimenarche, after puberty, and in early reproductive life is referred to as the original SCJ, because this represents the junction between the columnar epithelium and the original squamous epithelium laid down during embryogenesis in intrauterine life. During childhood and around the menarche, the original SCJ is located at, or very close to, the external os ().

During childhood and around the menarche, the original SCJ is located at, or very close to, the external os ().

Fig. 2.8

Before puberty, the squamocolumnar junction is positioned above and very close to the external os.

After puberty and during the reproductive period, the female genital organs develop under the influence of estrogen. Thus, the cervix swells and enlarges and the endocervical canal elongates. This leads to eversion of the columnar epithelium in the lower part of the endocervical canal out onto the ectocervix (). This condition is called ectropion or ectopy, which is visible as a strikingly reddish-looking ectocervix on visual inspection (). It is sometimes called an erosion or ulcer, which are misnomers. Thus, the original SCJ is located on the ectocervix, far away from the external os (). An ectropion may begin or become much more pronounced during pregnancy.

Fig. 2.9

The squamocolumnar junction after eversion of the columnar epithelium out onto the ectocervix, which occurs most commonly during adolescence and early pregnancy.

Fig. 2.10

(a) Ectropion with the original squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) situated on the ectocervix. Inside or proximal to this is an area of columnar epithelium. (b) Ectropion with the original SCJ situated on the ectocervix. Inside or proximal (more...)

The buffer action of the mucus covering the columnar cells is interfered with when the everted columnar epithelium of an ectropion is exposed to the acidic vaginal environment. This leads to the destruction and eventual replacement of the columnar epithelium by the newly formed metaplastic squamous epithelium (metaplasia refers to the change or replacement of one type of epithelium by another).

The metaplastic process starts at the original SCJ and proceeds centripetally towards the external os throughout the reproductive period and finally to the menopause. It is also thought that some metaplasia may occur by ingrowth of the squamous epithelium from the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix. Thus, a new SCJ is formed between the newly formed metaplastic squamous epithelium and the columnar epithelium ().

Fig. 2.11

(a) The incomplete metaplasia that has occurred in the ectocervical columnar epithelium produces a mixed squamous/columnar epithelium in the physiological transformation zone (TZ), lying between the labels a and b in the drawing. (b) The (more...)

As the woman passes from reproductive to perimenopausal life, the new SCJ moves towards the external os (). Hence, it is located at a variable distance from the external os, as a result of the progressive formation of new metaplastic squamous epithelium on the exposed areas of the columnar epithelium in the ectocervix. From the perimenopausal period and afterwards, the atrophic cervix shrinks, and consequently, the movement of the new SCJ towards the external os and into the endocervical canal is accelerated. In postmenopausal women, the new SCJ is often invisible on visual examination, because it has become entirely endocervical. The new SCJ is usually simply referred to as the SCJ.

Fig.

2.12

2.12Development of the transformation zone from fetal life to postmenopausal life.

2.2. Ectropion or ectopy

Ectropion or ectopy is defined as the presence of everted endocervical columnar epithelium on the ectocervix. It appears as a large reddish area on the ectocervix surrounding the external os (). The eversion of the columnar epithelium is usually more pronounced on the anterior and posterior lips of the ectocervix, and less so laterally. This is a normal, physiological occurrence. Occasionally, the columnar epithelium extends to the vaginal fornix. The whole mucosa, including the crypts and the supporting stroma, is displaced in ectropion. It is the region in which physiological transformation to squamous metaplasia occurs, and it is the area that is susceptible to cervical squamous disease.

2.3. Squamous metaplasia

The physiological replacement of the everted columnar epithelium by squamous epithelium is called squamous metaplasia. The vaginal environment is relatively acidic during reproductive life and during pregnancy. The acidity is thought to play a role in squamous metaplasia. The columnar cells exposed are eventually replaced by metaplastic squamous epithelium. Initially, the irritation of exposed columnar epithelium by the acidic vaginal environment results in the appearance of subcolumnar reserve cells, and these cells proliferate, producing reserve cell hyperplasia, and eventually become metaplastic squamous epithelium. The reserve cells multiply, differentiate, and eventually lift off the columnar epithelium (). The exact origin of the reserve cells is not known.

The acidity is thought to play a role in squamous metaplasia. The columnar cells exposed are eventually replaced by metaplastic squamous epithelium. Initially, the irritation of exposed columnar epithelium by the acidic vaginal environment results in the appearance of subcolumnar reserve cells, and these cells proliferate, producing reserve cell hyperplasia, and eventually become metaplastic squamous epithelium. The reserve cells multiply, differentiate, and eventually lift off the columnar epithelium (). The exact origin of the reserve cells is not known.

Fig. 2.13

Development of squamous metaplastic epithelium. (a) The arrows indicate the subcolumnar reserve cells. (b) The reserve cells proliferate. (c) The reserve cells further proliferate and differentiate. (d) Mature squamous (more...)

The first sign of squamous metaplasia is the appearance and proliferation of reserve cells (). This is initially seen as a single layer of small, round cells with dark-staining nuclei, situated very close to the nuclei of columnar cells, which further proliferate to produce reserve cell hyperplasia (). Morphologically, the reserve cells have a similar appearance to the basal cells of the original squamous epithelium, with round nuclei and little cytoplasm. As the metaplastic process progresses, the reserve cells proliferate and differentiate to form a thin, multicellular epithelium of immature squamous cells with no evidence of stratification (). The term “immature squamous metaplastic epithelium” is used when there is little or no stratification in this thin, newly formed metaplastic epithelium. Immature squamous metaplastic epithelium does not produce glycogen and, hence, does not stain brown or black with Lugol’s iodine. Groups of mucin-containing columnar cells may be seen embedded in the immature squamous metaplastic epithelium at this stage.

Morphologically, the reserve cells have a similar appearance to the basal cells of the original squamous epithelium, with round nuclei and little cytoplasm. As the metaplastic process progresses, the reserve cells proliferate and differentiate to form a thin, multicellular epithelium of immature squamous cells with no evidence of stratification (). The term “immature squamous metaplastic epithelium” is used when there is little or no stratification in this thin, newly formed metaplastic epithelium. Immature squamous metaplastic epithelium does not produce glycogen and, hence, does not stain brown or black with Lugol’s iodine. Groups of mucin-containing columnar cells may be seen embedded in the immature squamous metaplastic epithelium at this stage.

Numerous continuous and/or isolated fields or foci of immature squamous metaplasia may arise at the same time. It has been proposed that the basement membrane of the original columnar epithelium dissolves and is reformed between the proliferating and differentiating reserve cells and the cervical stroma. Squamous metaplasia usually begins at the original SCJ at the distal limit of the ectopy, but it may also occur in the columnar epithelium close to this junction or as islands scattered in the exposed columnar epithelium.

Squamous metaplasia usually begins at the original SCJ at the distal limit of the ectopy, but it may also occur in the columnar epithelium close to this junction or as islands scattered in the exposed columnar epithelium.

As the process continues, the immature metaplastic squamous cells differentiate into mature stratified metaplastic epithelium (). For all practical purposes, this resembles original stratified squamous epithelium. Some residual columnar cells or vacuoles of mucus are seen in the mature squamous metaplastic epithelium, which contains glycogen from the intermediate cell layer onward. Thus, the more mature the metaplasia is, the more it will stain brown or black after the application of Lugol’s iodine ().

Fig. 2.14

Uptake of Lugol’s iodine in the cervix of a premenopausal woman.

Inclusion cysts, also called nabothian follicles or nabothian cysts, may be observed in the TZ in mature metaplastic squamous epithelium (). Nabothian cysts are retention cysts that develop as a result of the occlusion of an endocervical crypt opening or outlet by the overlying metaplastic squamous epithelium. The buried columnar epithelium continues to secrete mucus, which eventually fills and distends the cyst. The columnar epithelium in the wall of the cyst is flattened and ultimately destroyed by the pressure of the mucus in it. The outlets of the crypts of columnar epithelium, not yet covered by the metaplastic epithelium, remain as persistent crypt openings (). The farthest extent of the metaplastic epithelium onto the ectocervix can be best judged by the location of the crypt opening farthest away from the SCJ. is a diagrammatic representation of normal TZ tissue components.

The buried columnar epithelium continues to secrete mucus, which eventually fills and distends the cyst. The columnar epithelium in the wall of the cyst is flattened and ultimately destroyed by the pressure of the mucus in it. The outlets of the crypts of columnar epithelium, not yet covered by the metaplastic epithelium, remain as persistent crypt openings (). The farthest extent of the metaplastic epithelium onto the ectocervix can be best judged by the location of the crypt opening farthest away from the SCJ. is a diagrammatic representation of normal TZ tissue components.

Fig. 2.15

A nabothian follicle is seen at the 7 o’clock position in this image of a normal transformation zone. There is a little light reflection seen at its tip.

Fig. 2.16

Epithelial components of the transformation zone.

Squamous metaplasia is an irreversible process; the transformed epithelium (now squamous in character) cannot revert to columnar epithelium. The metaplastic process in the cervix is sometimes referred to as indirect metaplasia, because the columnar cells do not transform into squamous cells but are replaced by the proliferating subcolumnar cuboidal reserve cells. Squamous metaplasia may progress at varying rates in different areas of the same cervix, and hence many areas of widely differing maturity may be seen in the metaplastic squamous epithelium with or without islands of columnar epithelium. The metaplastic epithelium adjacent to the SCJ is composed of immature metaplasia, and the mature metaplastic epithelium is found near the original SCJ.

Squamous metaplasia may progress at varying rates in different areas of the same cervix, and hence many areas of widely differing maturity may be seen in the metaplastic squamous epithelium with or without islands of columnar epithelium. The metaplastic epithelium adjacent to the SCJ is composed of immature metaplasia, and the mature metaplastic epithelium is found near the original SCJ.

Further development of the newly formed immature metaplastic epithelium may take two directions. In the vast majority of women, it develops into mature squamous metaplastic epithelium, which is similar to the normal glycogen-containing original squamous epithelium for all practical purposes. In a very small minority of women, an atypical, dysplastic epithelium may develop. Certain oncogenic HPV types may infect the immature basal squamous metaplastic cells and, rarely, turn them into precancerous cells. The uncontrolled proliferation and expansion of these atypical cells may lead to the formation of an abnormal dysplastic epithelium, which may regress to normal, persist as dysplasia, or progress to invasive cancer after several years, depending on whether the HPV infection is allowed to become a transforming infection (see Chapter 4).

2.4. Transformation zone (TZ)

The TZ is that area of epithelium that lies between the native and unaffected columnar epithelium of the endocervical canal and the native squamous epithelium deriving from the vaginal and ectocervical squamous epithelium ().

Fig. 2.17

(a) Schematic diagram of the normal transformation zone. (b) Schematic diagram of the abnormal or atypical transformation zone harbouring dysplasia.

The eversion of endocervical epithelium from inside the endocervical canal onto the outside of the cervix, i.e. the ectocervix, takes place at variable times and rates, but generally speaking it occurs during adolescence and during a first pregnancy (). As a result, the columnar epithelium on the ectocervix is exposed to the relatively acidic vaginal environment and undergoes squamous metaplasia, producing the physiological TZ, as described above. This process, when complete, probably results in protection from HPV infection, but during this process the dynamic TZ is susceptible to HPV infection, whereby it may infect the basal layers of the epithelium in the TZ and, in a small proportion of cases, initiate the development of CIN (). Why this dysplastic epithelium develops in some women and not in others is currently uncertain, but it is associated with oncogenic HPV types in 99% of cases. Most people will be infected with oncogenic HPV types early on in their normal sexual life, but the great majority will clear the infection without consequence (see Chapter 4). When the TZ becomes abnormal or atypical, it is called the atypical TZ. The components of the TZ are also depicted in .

Why this dysplastic epithelium develops in some women and not in others is currently uncertain, but it is associated with oncogenic HPV types in 99% of cases. Most people will be infected with oncogenic HPV types early on in their normal sexual life, but the great majority will clear the infection without consequence (see Chapter 4). When the TZ becomes abnormal or atypical, it is called the atypical TZ. The components of the TZ are also depicted in .

Fig. 2.18

Effect of infection with oncogenic HPV on immature squamous epithelium.

The TZ varies in its size and its precise position on the cervix, and it may lie partially or completely in the endocervical canal. Where it is and how visible it is determine its type (see Annex 1). In most women of reproductive age, the TZ is of type 1, and the magnified and light-illuminated view afforded by colposcopy will usually present the colposcopist with a clear view of all the components of the TZ as well as the native squamous epithelium and the native and untransformed columnar epithelium of the endocervical canal (). Occasionally (in about 4% of cases), the examination will reveal a so-called original or congenital TZ, as depicted in .

Occasionally (in about 4% of cases), the examination will reveal a so-called original or congenital TZ, as depicted in .

Fig. 2.19

The typical congenital or original transformation zone (TZ).

2.4.1. Congenital transformation zone

During early embryonic life, the cuboidal epithelium of the vaginal tube is replaced by the squamous epithelium, which begins at the caudal end of the dorsal urogenital sinus. This process is completed well before birth, and the entire length of the vagina and the ectocervix is normally covered by squamous epithelium. This process proceeds very rapidly along the lateral walls, and later in the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. If the epithelialization proceeds normally, the original SCJ will be located at the external os at birth. If this process is arrested for some reason, or incomplete, the original SCJ will be located distal to the external os or may rarely be located on the vaginal walls, particularly involving the anterior and posterior fornices. The cuboidal epithelium remaining here will undergo squamous metaplasia. This late conversion to squamous epithelium in the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, as well as the ectocervix, results in the formation of the congenital TZ. Thus, it is a variant of intrauterine squamous metaplasia in which differentiation of the squamous epithelium is not fully completed because of an interference with normal maturation. Excessive maturation is seen on the surface (as evidenced by keratinization), with delayed, incomplete maturation in deeper layers. Clinically, it may be seen as an extensive whitish-grey, hyperkeratotic area extending from the anterior and posterior lips of the cervix to the vaginal fornices. Gradual maturation of the epithelium may occur over several years. This type of TZ is seen in fewer than 5% of women and is a variant of the normal TZ.

Box

Key points.

Cervix (Human Anatomy): Diagram, Location, Conditions, Treatment

Human Anatomy

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

Medically Reviewed by Neha Pathak, MD on December 20, 2020

Image Source

© 2014 WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.

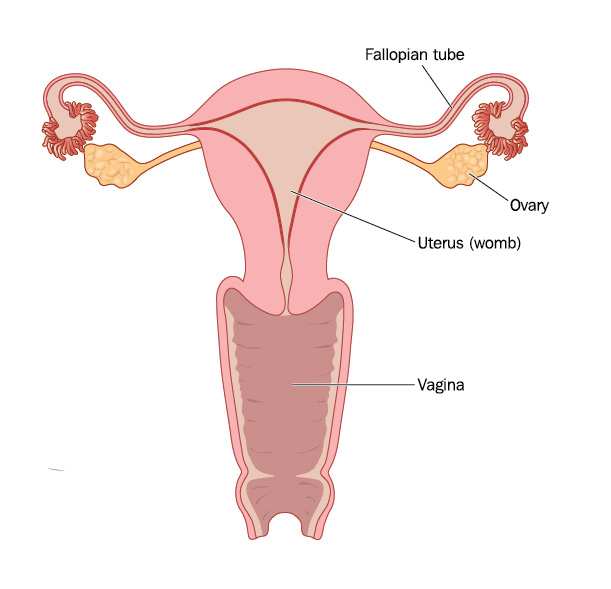

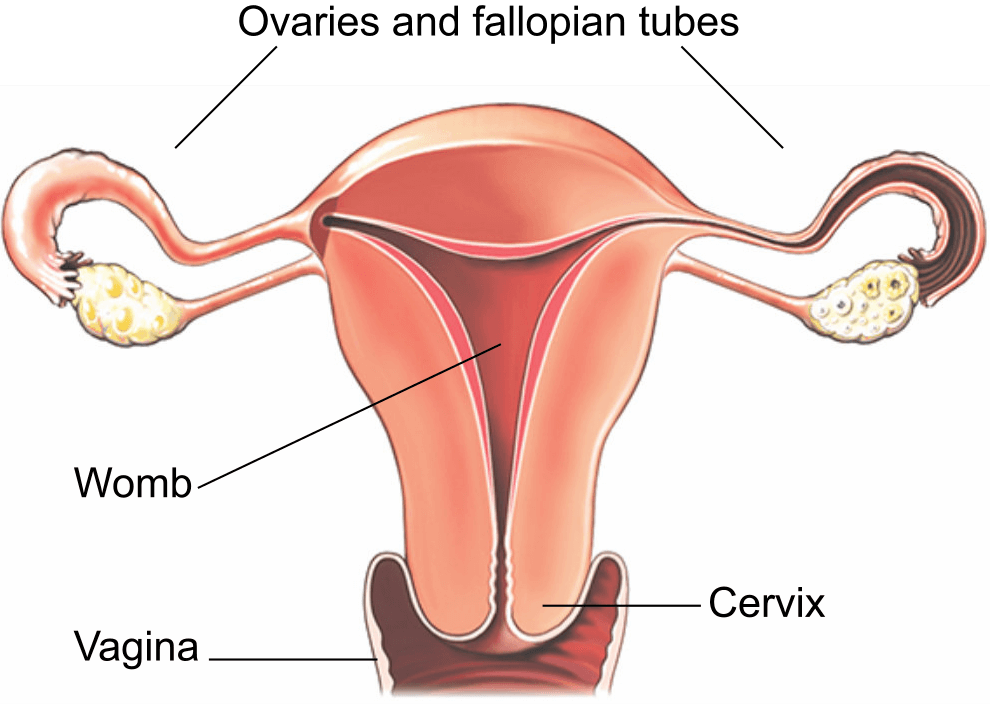

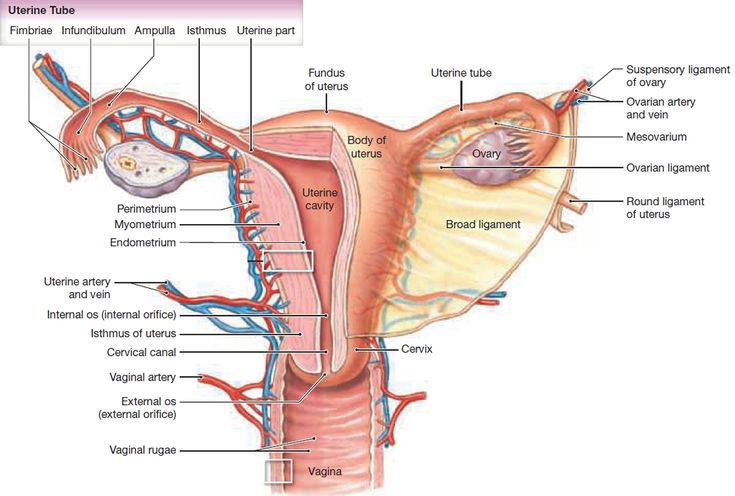

The cervix is a cylinder-shaped neck of tissue that connects the vagina and uterus. Located at the lowermost portion of the uterus, the cervix is composed primarily of fibromuscular tissue. There are two main portions of the cervix:

- The part of the cervix that can be seen from inside the vagina during a gynecologic examination is known as the ectocervix. An opening in the center of the ectocervix, known as the external os, opens to allow passage between the uterus and vagina.

- The endocervix, or endocervical canal, is a tunnel through the cervix, from the external os into the uterus.

The overlapping border between the endocervix and ectocervix is called the transformation zone.

The cervix produces cervical mucus that changes in consistency during the menstrual cycle to prevent or promote pregnancy.

During childbirth, the cervix dilates widely to allow the baby to pass through. During menstruation, the cervix opens a small amount to permit passage of menstrual flow.

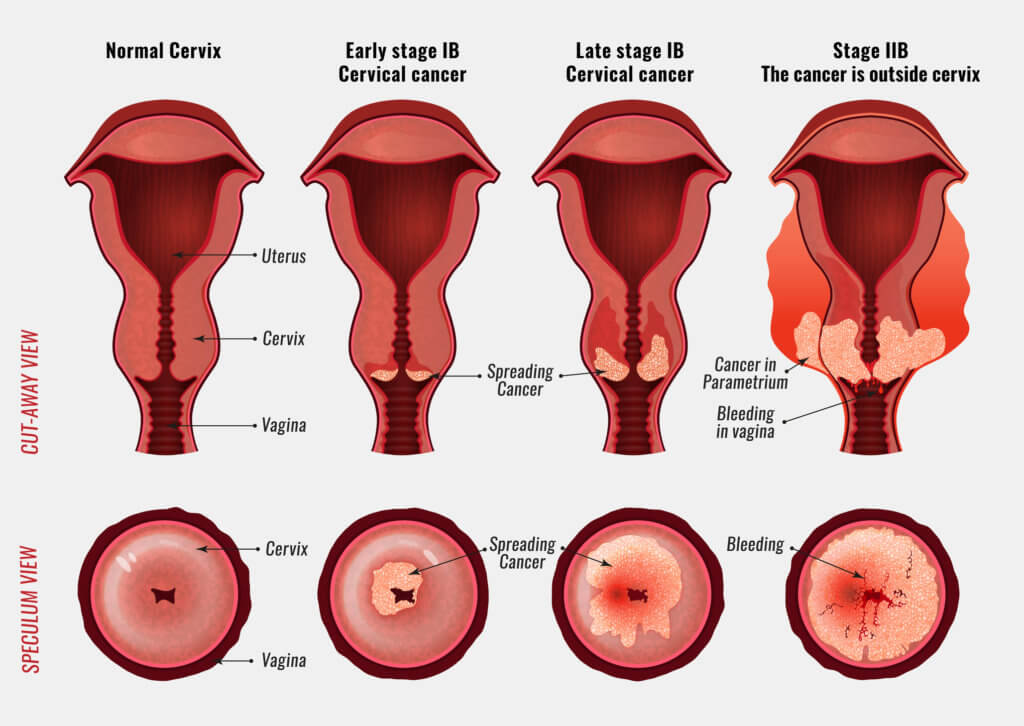

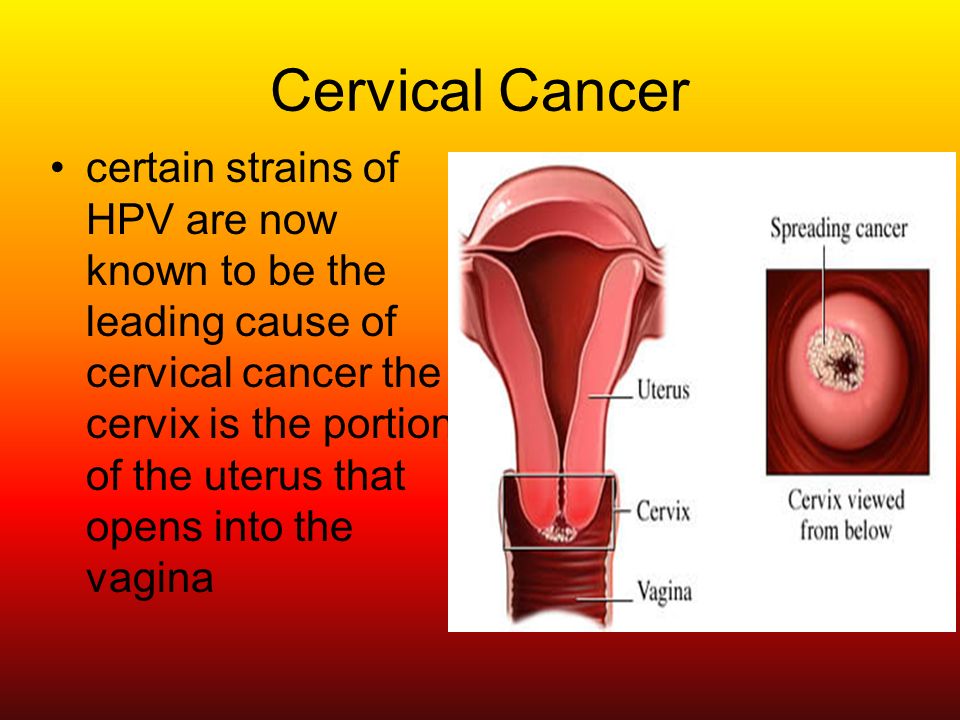

Cervix Conditions

- Cervical cancer: Most cervical cancer is caused by infection by the human papillomavirus (HPV). Regular Pap tests can prevent cervical cancer in most women.

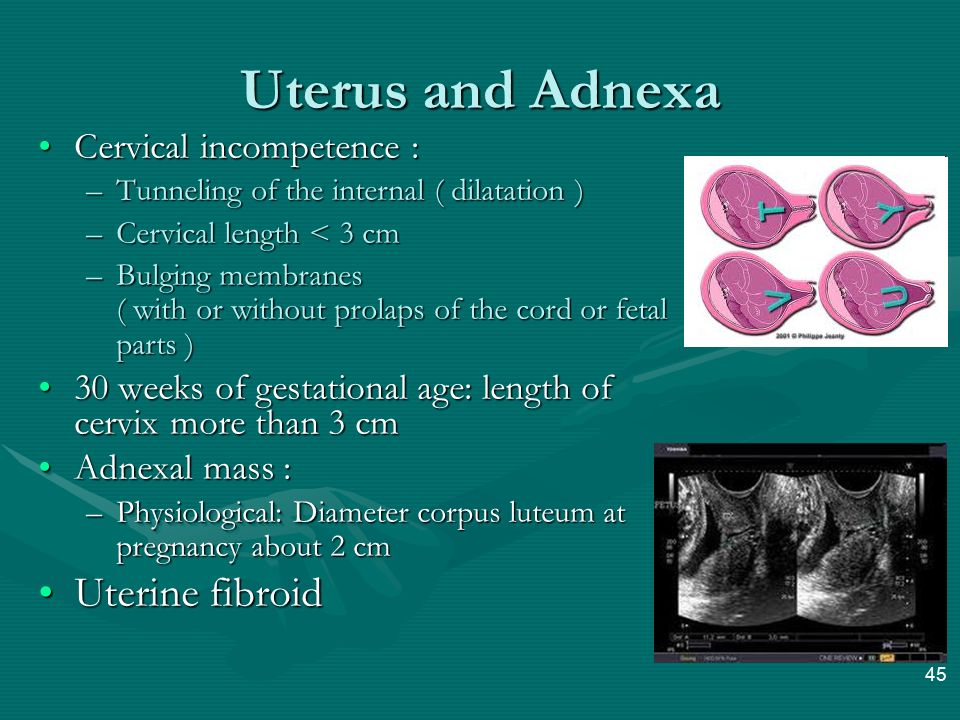

- Cervical incompetence: Early opening, or dilation, of the cervix during pregnancy that can lead to premature delivery. Previous procedures on the cervix are often responsible.

- Cervicitis: Inflammation of the cervix, usually caused by infection. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and herpes are some of the sexually transmitted infections that can cause cervicitis.

- Cervical dysplasia: Abnormal cells in the cervix that can become cervical cancer. Cervical dysplasia is frequently discovered on Pap test.

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN): Another name for cervical dysplasia.

- Cervix polyps: Small growths on the part of the cervix where it connects to the vagina. Polyps are painless and usually harmless, but they can cause vaginal bleeding.

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): Infection of the cervix, known as cervicitis, may spread into the uterus and fallopian tubes.

Pelvic inflammatory disease can damage a woman's reproductive organs and make it more difficult for them to become pregnant.

Pelvic inflammatory disease can damage a woman's reproductive organs and make it more difficult for them to become pregnant. - Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: Human papillomaviruses are a group of viruses, including certain types that cause cervical cancer. Less dangerous types of the virus cause genital and cervical warts.

Cervix Tests

- Pap test: A sample of cells is taken from a woman's cervix and examined for signs of changes. Pap tests may detect cervical dysplasia or cervical cancer.

- Cervical biopsy: A health care provider takes a sample of tissue, or biopsy, from the cervix to check for cervical cancer or other conditions. Cervical biopsy is often done during colposcopy.

- Colposcopy: A follow-up test for an abnormal Pap test. A gynecologist views the cervix with a magnifying glass, known as a colposcope, and may take a biopsy of any areas that do not look healthy.

- Cone biopsy: A cervical biopsy in which a cone-shaped wedge of tissue is removed from the cervix and examined under a microscope.

Cone biopsy is performed after an abnormal Pap test, both to identify and to remove dangerous cells in the cervix.

Cone biopsy is performed after an abnormal Pap test, both to identify and to remove dangerous cells in the cervix. - Computed tomography (CT scan): A CT scanner takes multiple X-rays, and a computer creates detailed images of the cervix and other structures in the abdomen and pelvis. CT scanning is often used to determine whether cervical cancer has spread, and if so, how far.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan): An MRI scanner uses a high-powered magnet and a computer to create high-resolution images of the cervix and other structures in the abdomen and pelvis. Like CT scans, MRI scans can be used to look for the spread of cervical cancer.

- Positron emission tomography (PET scan): A test to look for spread or recurrence of cervical cancer. A solution, known as a tracer solution, containing a mildly radioactive chemical is injected into the veins. The PET scan takes pictures as this solution moves through the body. Any areas of cancer take up the tracer and "light up" on scanner images.

- HPV DNA test: Cervical cells can be tested for the presence of DNA from human papillomavirus (HPV). This test can identify whether the types of HPV that can cause cervical cancer are present.

Cervix Treatments

- Cervical cerclage: In women with cervical incompetence, the cervix can be sewn closed. This can prevent early opening of the cervix during pregnancy, which can cause premature delivery.

- Antibiotics: Medications that can kill the bacteria that causes infections of the cervix and reproductive organs. Antibiotics may be taken orally or given through a vein, or intravenously, for serious infections.

- Cryotherapy: An extremely cold probe is placed against abnormal areas on the cervix. Freezing kills the abnormal cells, preventing them from becoming cervical cancer.

- Laser therapy: A high-energy laser is used to burn areas of abnormal cells in the cervix. The abnormal cells are destroyed, preventing them from becoming cervical cancer.

- Cervical cancer vaccine: To prevent cervical cancer, a vaccine against certain strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) is recommended for most adolescent girls and young women.

- Chemotherapy: Cancer medications that are usually injected into a vein. Chemotherapy is usually given for cervical cancer that is believed to have spread.

- Total Hysterectomy: Surgical removal of the uterus and cervix. If cervical cancer has not spread, hysterectomy can offer a complete cure.

- Cone biopsy: A cervical biopsy that removes a cone-shaped wedge of tissue from the cervix. Because a large portion of the cervix is removed, cone biopsy can help prevent or treat cervical cancer.

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP): An electrified wire loop is touched against abnormal cells in the cervix. The electrical current destroys the cells, preventing or treating cervical cancer.

- Radiation therapy: Using radioactive energy to kill cervical cancer cells. Radiation therapy is given as a beam from outside the body or in small pellets implanted in the cervix, known as brachytherapy.

The structure of the cervix: description, colpophotogram

The structure of the cervix

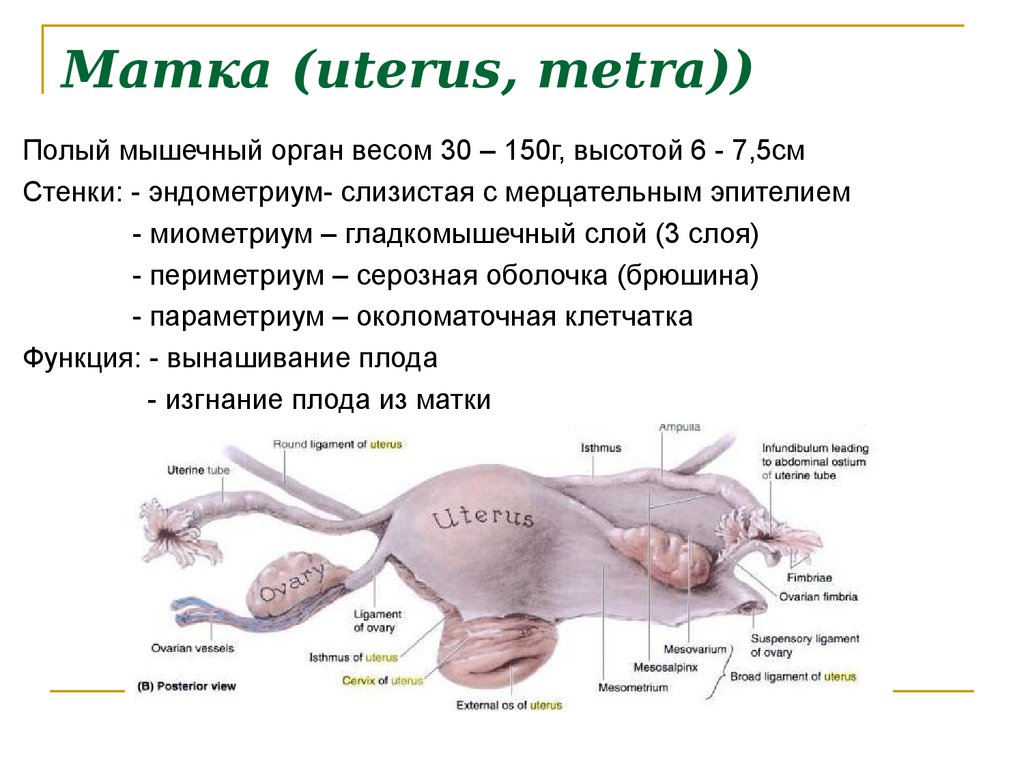

The cervix is a part of the uterus, which at one end is partially located in the vagina, and at the other through the internal pharynx passes into the cavity of the uterine body.

It has the shape of a cylinder with a channel inside. Through the outer hole, the so-called. external os, the cervical canal opens into the vagina. Through the inner hole, the so-called. internal os, the cervical canal opens and connects with the uterine cavity. The overall dimensions of the cervix can vary from 2-3 cm to 4-6 cm, both in length and in diameter.

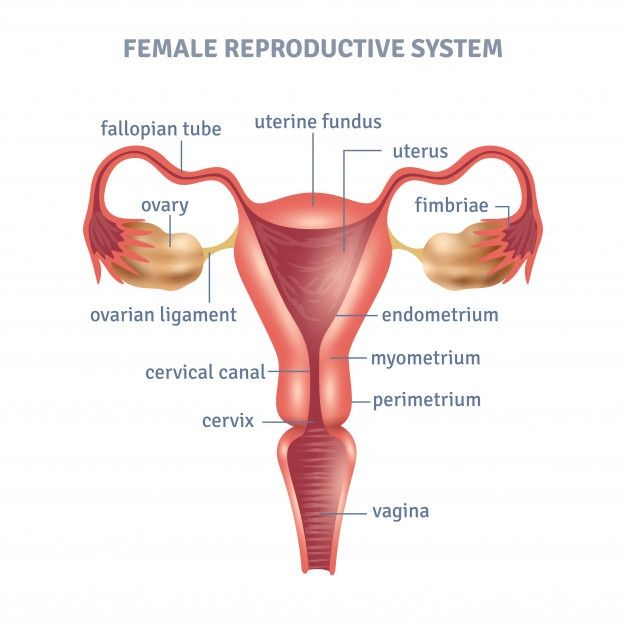

Fig.1 . Schematic representation of the internal genitalia

The cervix is a muscular-connective tissue organ, which is covered with epithelial tissue. In the connective tissue are blood and lymphatic vessels, muscle tissue is represented by smooth muscles. The main part of the muscle tissue is located in the upper part of the cervix in the form of a ring and performs a locking function. Closer to the vaginal part, the cervix contains mostly connective tissue fibers. Epithelial tissue covers the cervix from the vaginal part and inside the cervical canal.

The main part of the muscle tissue is located in the upper part of the cervix in the form of a ring and performs a locking function. Closer to the vaginal part, the cervix contains mostly connective tissue fibers. Epithelial tissue covers the cervix from the vaginal part and inside the cervical canal.

The part of the cervix that is located in the vagina and is visible to the doctor during examination is called the ectocervix. This part of the cervix has a smooth surface, covered with stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium, the same as the vagina, and the mucous membrane of the labia minora.

Fig.2 . Microphotogram of normal stratified squamous epithelium. The microphotogram was kindly provided by Mikhail Krotevich, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Pathology of the National Cancer Institute

This epithelium is smooth, pink, resistant to mechanical stress and the acidic environment of the vagina. Stratified squamous epithelium performs a protective function. It is quickly updated and restored in case of mechanical injuries. Complete renewal of the epithelial layer occurs in 4-5 days.

It is quickly updated and restored in case of mechanical injuries. Complete renewal of the epithelial layer occurs in 4-5 days.

Fig.3 . On the colpophotogram, the cervix is covered with normal stratified squamous epithelium.

In the cervical canal the mucous membrane has a folded shape, is represented by multiple bends of the connective tissue, which resemble glands, is covered with a single layer of delicate epithelium - columnar epithelium. This epithelium produces clear mucus. Mucus in the cervical canal forms a mucous plug. The nature and type of cervical mucus changes with the phases of the menstrual cycle. In the first phase of the mucus cycle, there is a little more; during ovulation, it becomes transparent and viscous.

Stratified squamous epithelium and columnar epithelium meet at the external os and form a junction line.

Fig.4 . The colpophotogram shows the cervix during ovulation. In the cervical canal, there is transparent mucus, the mucous membrane of the cervical canal is visible, the junction line of two types of epithelium at the level of the external os.

In the cervical canal, there is transparent mucus, the mucous membrane of the cervical canal is visible, the junction line of two types of epithelium at the level of the external os.

The joint is necessary and desirable to be visualized during colposcopy, and it must necessarily fall into the area of taking a cytological smear (Pap test).

Why is this important?

It is known that the main cause of dysplasia and cervical cancer is the human papillomavirus. This virus can only replicate in actively dividing cells. Such cells are found in the stratified squamous epithelium in its lowest layers - basal cells. However, with the preserved integrity of the epithelium, they are reliably protected by the upper layers. The only "weak" place on the cervix, where the virus can "get" to such cells, is the junction.

Fig. 5 . Schematic representation of the junction of stratified squamous epithelium and cylindrical. It is clearly seen that the basal cells at the junction are located close to the surface - this is the "weak link".

There, the lower (basal) cells rise to the surface and remain vulnerable to the virus. As a rule, all pathological processes in the epithelium of the cervix begin to occur in the junction area, so it is important to have a mandatory colposcopic and cytological examination of this area of the cervix.

The third normal type of cervical epithelium is the metaplastic epithelium. The word "metaplasia" scares patients somewhat, because it is somewhat consonant with the word "metastasis", but it has nothing to do with it.

Fig. 6 . The colpogram shows the cervix with a small ectopia of the cylindrical epithelium and a type 1 transformation zone of the cervix (metaplastic epithelium and multiple open glands), the junction is clearly visible, which is located on the outer part of the cervix - the ectocervix.

Metaplastic epithelium arises from reserve cells, the so-called. bipotent cells, or in other words, cells that have two possibilities for development. These cells are able, depending on the conditions, to transform either into cells of a cylindrical or into cells of a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium through the process of metaplasia. The process of metaplasia is stepwise. Metaplasia is early, immature and mature. In terms of properties and appearance, early metaplasia cells are similar to cells of a cylindrical epithelium; very early metaplasia can sometimes imitate a malignant process for an inexperienced morphologist (histologist or cytologist). According to the degree of maturation, metaplasia acquires the properties of a stratified squamous epithelium. If nothing interferes with the process of metaplasia (trauma, inflammation, infection with HPV), then it ends with the formation of a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium. The process of metaplasia occurs on the cervix in the presence of ectopia on it columnar epithelium , as well as in the process of healing epithelial defects - erosion and abrasions, injuries.

These cells are able, depending on the conditions, to transform either into cells of a cylindrical or into cells of a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium through the process of metaplasia. The process of metaplasia is stepwise. Metaplasia is early, immature and mature. In terms of properties and appearance, early metaplasia cells are similar to cells of a cylindrical epithelium; very early metaplasia can sometimes imitate a malignant process for an inexperienced morphologist (histologist or cytologist). According to the degree of maturation, metaplasia acquires the properties of a stratified squamous epithelium. If nothing interferes with the process of metaplasia (trauma, inflammation, infection with HPV), then it ends with the formation of a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium. The process of metaplasia occurs on the cervix in the presence of ectopia on it columnar epithelium , as well as in the process of healing epithelial defects - erosion and abrasions, injuries.

The entire surface area of the cervix, on which metaplasia occurs, is called the transformation zone of the cervix (restructuring zone, Fig. 6, 7). This is the place where the processes of transformation of the epithelium are actively taking place, and these areas of the cervix are very sensitive to the negative effects of the human papillomavirus.

Fig.7 . Microphotogram. Transformation zone of the cervix under the microscope: stratified squamous epithelium, columnar epithelium, metaplastic epithelium, junction line. The microphotogram was kindly provided by Mikhail Krotevich, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Pathology of the National Cancer Institute.

It is very important to examine this area colposcopically and cytologically, since the risk of developing precancer and cervical cancer is many hundreds of times higher in it than in stratified squamous epithelium outside this area.

Transformation zones of the cervix are divided into three types:

Fig. 8 . Transformation zone type 1 is located on the outer part of the cervix and is fully visible during colposcopy;

8 . Transformation zone type 1 is located on the outer part of the cervix and is fully visible during colposcopy;

Fig. 9 . Transformation zone type 2 is located on the outer part of the cervix, but also has a component located in the cervical canal, but is completely visible;

Fig. 10 . The type 3 transformation zone has an intracervical component and is not completely visible.

Cervix: general information, structure

Consultation with a specialist:

The structure of the cervix and its functions

The organ has a cylindrical shape, and its inner part is a hollow “tube” lined with epithelial tissue.

The cervix is divided into two regions:

- Vaginal. Enters the vaginal cavity. It has a convex shape. Lined with stratified squamous epithelium.

- Supravaginal. Lies above the vagina.

Lined with columnar epithelium.

Lined with columnar epithelium.

The area where the squamous epithelium of the vaginal part changes to the cylindrical epithelium of the cervical canal is called the transformation zone.

The cervical canal is the central part of the cervix. It has an internal pharynx that goes to the body of the uterus, as well as an external one facing the vagina - it is seen by the gynecologist when examining the patient. In nulliparous women, the external os has a round or oval shape, in those who have given birth, it is slit-like. The channel always contains a certain amount of mucus.

Cervical mucus is a biological fluid, the importance of which in a woman's reproductive health can hardly be overestimated.

It has antibacterial properties and prevents infection from entering the uterine cavity. When a woman becomes pregnant, the cervical canal is closed with a dense mucous plug, which reliably protects the fetus from pathogenic microorganisms.

The rheological characteristics of cervical mucus change depending on the woman's monthly cycle. During ovulation and menstruation, it becomes more fluid. In the first case, it helps the sperm to move through the canal, which means it promotes conception. In the second, it facilitates the outflow of menstrual blood.

Call right now

+7 (495) 215-56-90

Sign up

Pregnancy cervix

The task of the cervix during this period is to protect the fetus from infection and prevent abortion or premature birth.

Shortly after conception, the following changes occur in it:

- The pink surface of the channel takes on a bluish tint due to the increased pattern of blood vessels. This is facilitated by intensive blood circulation in the uterus.

- The mucous membrane becomes softer. This is also due to increased blood circulation and mucus secretion.

- The cervix descends, and the lumen of the canal narrows and is tightly “sealed” with a cork.

According to these changes, the gynecologist can visually determine pregnancy a few weeks after conception.

As the fetus develops in the womb, the length of the cervix gradually decreases. It is very important that it matches the gestational age, since a too short neck can threaten miscarriage or premature birth.

In the third trimester, the cervix becomes shorter, softer, and closer to childbirth, it begins to open slightly. The mucus plug may come off within a few weeks of labor.

Cervix and childbirth

Before the onset of active labor activity, the organ shortens to 1 cm and its anatomical position changes. The neck, previously directed slightly backward, moves to the center and is located under the head of the child.

As labor proceeds, the cervix shortens and smoothes, and its lumen gradually opens so that the baby's head can pass through it. Full dilatation of the cervix - about 10 cm.

Full dilatation of the cervix - about 10 cm.

At the first birth, the internal os opens first, and then the external one. With subsequent disclosure occurs at the same time, so childbirth is faster.

Diseases of the cervix

Diseases of this organ are divided into the following types:

- Background - not associated with malignant processes.

- Precancerous (dysplasia) - there are areas with damaged cell structure (atypical cells), but without malignant changes.

- Cancer - malignant changes in the cellular structure.

Most of the diseases of the cervix occur without symptoms. In some cases, they may be accompanied by increased discharge, discomfort during sexual contact, bloody discharge. But even cervical cancer can give severe symptoms only at a late stage, when the disease is difficult to cure.

Cervical pathology can only be detected by specialized methods during a gynecological examination.

These methods include:

- Pap smear. Allows you to suspect the presence of atypical cells and the degree of their damage, to identify the inflammatory process in the cervix. Based on the results of the Pap test, further examination of the patient is performed.

- Colposcopy. Visual examination of the mucous membrane of an organ using an optical device - a colposcope. During colposcopy, various tests can be performed to identify damaged areas, as well as a tissue fragment (biopsy) is taken to perform a histological examination.

- Histological analysis. The study of the cellular structure of the selected biomaterial under a microscope. The diagnosis of "dysplasia" and "cervical cancer" can only be made based on the results of histology.

- Flora smear. It is performed to identify pathogenic flora and determine its sensitivity to antibiotics and antimycotics (antifungal drugs). The analysis is necessary for organizing the treatment of inflammatory processes.

Your doctor may also order blood tests for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and human papillomavirus (HPV). Some strains of HPV are oncogenic and provoke dysplasia and cervical cancer.

Oncological processes of the cervix are formed rather slowly, passing through three stages of dysplasia - mild, moderate and severe. And even the third degree of dysplasia can be treated with full preservation of the reproductive function of a woman.

Early stage cervical cancer also has a favorable prognosis for the patient if treatment was started on time. Whether the organ will be preserved at the same time, the doctor decides according to indications.

At later stages, a radical hysterectomy is practiced - removal of the uterus with appendages, pelvic lymph nodes and the upper region of the vagina.

We repeat that dysplasia and subsequently cervical cancer develop slowly, almost asymptomatically, but are easily diagnosed during a medical examination. Whether a woman gets this type of cancer or not is largely a matter of her personal responsibility. An annual visit to a gynecologist for preventive examinations will protect you from this serious illness and preserve your reproductive health.

Whether a woman gets this type of cancer or not is largely a matter of her personal responsibility. An annual visit to a gynecologist for preventive examinations will protect you from this serious illness and preserve your reproductive health.

Call now

+7 (495) 215-56-90

Make an appointment

About clinic

Otradnoye Polyclinic is the largest multidisciplinary medical center in Moscow.

About 3,500 types of medical services for adults and children are provided on 4 floors in one building. More than 80 doctors serve thousands of patients per month.

The services of the center are available to all segments of the population, and treatment and diagnostic procedures are carried out according to modern protocols.

Our clinic has a diagnostic base for a complete examination, and surgeons perform operations both on an outpatient basis and in a well-equipped hospital.

_c53bbd6a-f309-45f6-b20e-2eb8914f5c67-eeeb18.jpg)