Why does baby heart rate drop

Understanding labor and delivery complications – diagnosis and treatment

What Are Common Labor and Delivery Complications?

A pregnancy that has gone smoothly can still have problems when it's time to deliver the baby. Your doctor and hospital are prepared to handle them. Here are some of the most common concerns:

Preterm labor and premature delivery

One of the greatest dangers babies face is being born too early, before their body is mature enough to survive outside the womb. The lungs, for example, may not be able to breathe air, or the baby's body may not generate enough heat to keep warm.

A full-term pregnancy lasts about 40 weeks. Having labor contractions before 37 weeks of pregnancy is called preterm labor. Also, a baby born before 37 weeks is considered a premature baby who is at risk of complications of prematurity, such as immature lungs, respiratory distress, and digestive problems.

Drugs and other treatments can be used to stop preterm labor. If these treatments fail, intensive care can keep many premature babies alive.

The symptoms of preterm labor and birth include:

- Contractions before 37 weeks of pregnancy, with a tightening and hardening of the uterine muscle, 10 minutes apart or less (these may be painless)

- Cramps similar to menstrual cramps (not to be mistaken with Braxton Hicks contractions, which typically are not at regular intervals and do not open the cervix)

- Low backache

- A feeling of pelvic pressure

- Abdominal cramps, gas, or diarrhea; in combination with contractions, may signal preterm labor

- Vaginal spotting or bleeding

- A change in quality or quantity of vaginal discharge, especially any gush or leak of fluid

Call you doctor if you notice or feel any of those symptoms.

Protracted labor

Protracted labor refers to cervical dilation that is abnormally slow or to abnormally slow fetal descent. This means the labor does not progress as fast as it should.

This could happen with a big baby, a baby in a breech position (buttocks down), or other abnormal presentation, or with a uterus that does not contract strongly enough. Often, there is no specific cause for protracted labor.

Both the mother and the baby are at risk for several complications, including infections, if the amniotic sac has been ruptured for a long time and the birth doesn't follow.

If labor goes on too long, the doctor may give IV fluids to prevent you from getting dehydrated. If the uterus does not contract enough, they may give you oxytocin, a drug that promotes stronger contractions. And if the cervix stops dilating despite strong contractions of the uterus, a C-section may be necessary.

Abnormal presentation

"Presentation" refers to the part of the baby that will appear first from the birth canal. In the weeks before your due date, the fetus usually drops lower in the uterus. Ideally, for labor, the baby is positioned head-down, facing the mother's back, with its chin tucked to its chest and the back of the head ready to enter the pelvis. That way, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the cervix and into the birth canal. This normal presentation is called vertex (head down) occiput anterior.

That way, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the cervix and into the birth canal. This normal presentation is called vertex (head down) occiput anterior.

Because the head is the largest and least flexible part of the baby, it's best for the head to lead the way into the birth canal. That way, there's little risk that the baby's body will make it through the birth canal, but the head will get caught.

Some babies present with their buttocks or feet pointed down toward the birth canal. This is called a breech presentation. Breech presentations are often seen during an ultrasound exam far before the due date, but most babies will turn to the normal head-down presentation as they get closer to the due date.

Types of breech presentation include:

- Frank breech. In a frank breech, the baby's buttocks lead the way into the pelvis; the hips are flexed, the knees extended.

- Complete breech. In a complete breech, both knees and hips are flexed, and the baby's buttocks or feet may enter the birth canal first.

- Incomplete breech. In an incomplete or footling breech, one or both feet lead the way.

Transverse lie is another type of presentation problem. A few babies lie horizontally in the uterus, called a transverse lie, which usually means the baby's shoulder will lead the way into the birth canal rather than the head.

In cephalopelvic disproportion, the baby's head is too large to fit through the mother's pelvis, either because of the size or because of the baby's poor positioning. Sometimes the baby is not facing the mother's back, but instead is turned toward their abdomen (occiput or cephalic posterior). This increases the chance of a lengthy, painful, childbirth, often called "back labor," or tearing of the birth canal.

In malpresentation, the baby is not "presenting" or positioned in the normal way. In malpresentation of the head, the baby's head is positioned wrong, with the forehead, top of the head, or face entering the birth canal, instead of the back of its head. Sometimes a placenta previa (when the placenta blocks the cervix) may cause an abnormal presentation. But many times the cause is not known.

Sometimes a placenta previa (when the placenta blocks the cervix) may cause an abnormal presentation. But many times the cause is not known.

Abnormal presentations increase a woman's risk for uterine or birth canal injuries and abnormal labor. Breech babies are at an increased risk of injury and a prolapsed umbilical cord, which cuts off the baby's blood supply. A transverse lie is the most serious abnormal presentation, and it can lead to injury of the uterus, as well as injury to the fetus.

Toward the end of your third trimester, your doctor will check the baby's presentation and position by feeling your belly or with ultrasound. If the fetus remains in breech presentation several weeks before the due date, your doctor may attempt to "turn" the baby into the correct position in a procedure called an "external version."

One way to try to turn the baby after 36 weeks is an external cephalic version, which involves a doctor manually rotating the baby by placing their hands on the mother's belly and turning the baby. These manipulations work about 50% to 60% of the time and are usually more successful on women who have given birth previously, because their uteruses stretch more easily. The procedure typically takes place in the hospital, in case an emergency C-section becomes necessary. To make the procedure easier to perform, safer for the baby, and more tolerable for the mother-to-be, doctors sometimes give a uterine muscle relaxant and then use an ultrasound and electronic fetal monitor as guides.

These manipulations work about 50% to 60% of the time and are usually more successful on women who have given birth previously, because their uteruses stretch more easily. The procedure typically takes place in the hospital, in case an emergency C-section becomes necessary. To make the procedure easier to perform, safer for the baby, and more tolerable for the mother-to-be, doctors sometimes give a uterine muscle relaxant and then use an ultrasound and electronic fetal monitor as guides.

If the first attempt is unsuccessful, turning the baby may be tried again with an epidural pain medication to help relax the uterine muscles. Since not all doctors have been trained to do versions, you may be referred to another obstetrician.

There is a very small risk that the maneuver could cause the baby's umbilical cord to become entangled or the placenta to separate from the uterus. There's also a chance (about 4%) that the baby might flip back into a breech position before delivery, so some doctors induce labor immediately. The closer you are to your due date, the lower the risk of reverting back to a breech position. But the bigger the baby, the harder it is to turn.

The closer you are to your due date, the lower the risk of reverting back to a breech position. But the bigger the baby, the harder it is to turn.

The procedure can be uncomfortable for the mother, but if successful, may avoid a C-section, which is more likely if the baby can't be moved into the proper position.

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM)

Normally, the membranes surrounding the baby in the uterus break and release amniotic fluid (known as the "water breaking") either right before or during labor. Premature rupture of membranes means that these membranes have ruptured too early in pregnancy, meaning prior to the onset of labor. This exposes the baby to a high risk of infection.

If the baby is mature enough to be born, your doctor will induce labor or do a C-section if necessary. If the baby isn't mature enough, you may be given antibiotics to prevent infection as well as other medications to try to prevent or slow preterm PROM.

Umbilical cord prolapse

The umbilical cord is your baby's lifeline. You pass oxygen and other nutrients from your body to your baby through the umbilical cord and placenta.

You pass oxygen and other nutrients from your body to your baby through the umbilical cord and placenta.

Sometimes, before or during labor, the umbilical cord can slip through the cervix after your water breaks, preceding the baby into the birth canal. The cord may even protrude from the vagina -- a dangerous situation because the blood flow through the umbilical cord can become blocked or stopped. You may feel the cord in the birth canal if it prolapses, and may see the cord if it protrudes from your vagina.

Umbilical cord prolapse happens more often when a baby is small, preterm, in breech presentation, or if its head hasn't entered the mother's pelvis yet. Cord prolapse can also occur if the amniotic sac breaks before the baby has moved into position in the pelvis. Umbilical cord prolapse is an emergency. If you aren't at the hospital when it happens, call an ambulance to take you there. Until help arrives, get on your hands and knees, with your chest on the floor and your buttocks raised. In this position, gravity will help keep the baby from pressing against the cord and cutting off their blood and oxygen supply. Once you get to the hospital, a C-section will be performed.

In this position, gravity will help keep the baby from pressing against the cord and cutting off their blood and oxygen supply. Once you get to the hospital, a C-section will be performed.

Umbilical cord compression

Because the fetus moves and kicks inside the uterus, the umbilical cord can wrap and unwrap itself around the baby many times throughout pregnancy. While there are "cord accidents" in which the cord gets twisted around and blocks blood supply to the baby, this is extremely rare and can't be prevented.

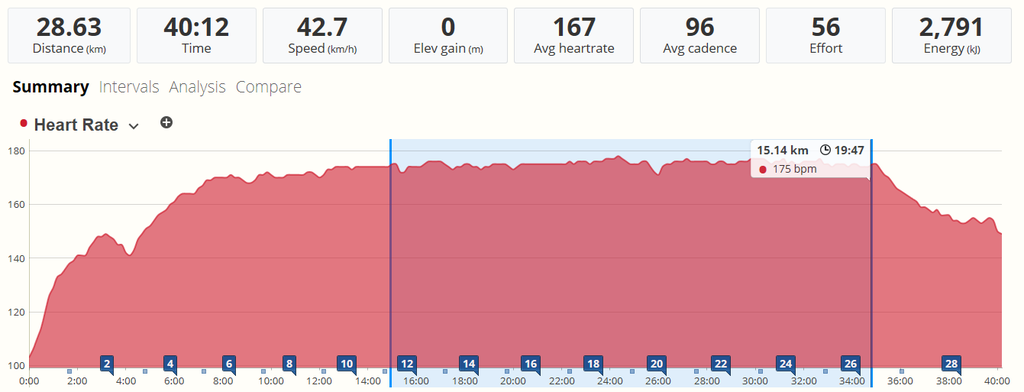

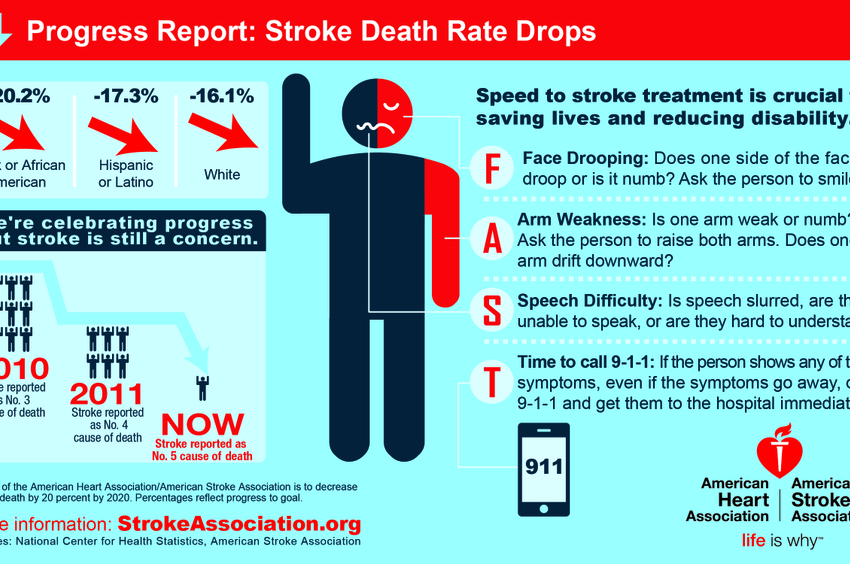

Sometimes the umbilical cord gets stretched and compressed during labor, leading to a brief decrease in blood flow to the fetus. This can cause sudden, short drops in fetal heart rate, called variable decelerations, which are usually picked up by monitors during labor. Cord compression happens in about one in 10 deliveries. In most cases, these heart rate changes are of no major concern, and the birth proceeds normally. But a C-section may be necessary if the baby's heart rate worsens or the baby shows other signs of distress.

Umbilical cord compression can occur if the cord becomes wrapped around the baby's neck or a limb or gets pressed between the baby's head and the mother's pelvic bone. You may be given oxygen to increase the oxygen available to your baby. Your doctor may hurry along the delivery by using forceps or vacuum assistance, or, in some cases, delivering the baby by C-section.

Amniotic fluid embolism

This is one of the most serious complications of labor and delivery. Very rarely, a small amount of amniotic fluid -- the fluid that surrounds the fetus in the uterus -- enters the mother's bloodstream, usually during a particularly difficult labor or a C-section. The fluid travels to the woman's lungs and may cause the arteries in the lungs to constrict. For the mother, this constriction can result in a rapid heart rate, irregular heart rhythm, collapse, shock, or even cardiac arrest and death. Widespread blood clotting is a common complication, requiring emergency care.

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a complication of pregnancy involving high blood pressure that develops after 20 weeks of pregnancy or shortly after delivery. Preeclampsia may lead to premature detachment of the placenta from the uterus, maternal seizure, or stroke.

Uterine bleeding (Postpartum hemorrhage)

After a baby is delivered, excessive bleeding from the uterus, cervix, or vagina, called postpartum hemorrhage, can be a major concern. Excessive bleeding may result when the contractions of the uterus after delivery are impaired, and the blood vessels that opened when the placenta detached from the wall of the uterus continue to bleed. It can also result from other causes such as cervical or vaginal lacerations.

Post-term pregnancy and post-maturity

In most pregnancies that go a little beyond 41 to 42 weeks, called late-term pregnancy, there are usually no problems. But problems may develop if the placenta can no longer provide enough nourishment to maintain a healthy environment for the baby. The risks can become significant in post-term pregnancies, those that go to 42 weeks or more.

The risks can become significant in post-term pregnancies, those that go to 42 weeks or more.

How Do I Prevent Problems With Labor and Delivery?

The most important thing you can do to try to have a healthy baby is getting early and adequate prenatal care. The best prenatal care begins even before you are pregnant, so you can be in the best of health before pregnancy.

To help prevent complications, if you smoke, quit. Smoking can trigger preterm labor. Researchers have found a link between gum disease and preterm birth, so brush and floss your teeth daily. It may also be helpful to reduce your stress level by setting aside quiet time every day and asking for help when you need it.

Transvaginal ultrasound

Your doctor will check you for risk factors for preterm labor and premature delivery, and discuss any precautions you should take. Measuring the length of the cervix using a transvaginal ultrasound probe can help predict a woman's risk of delivering prematurely. This procedure is usually done in a doctor's office between 20 and 28 weeks of pregnancy for women who may be at risk.

This procedure is usually done in a doctor's office between 20 and 28 weeks of pregnancy for women who may be at risk.

Fetal fibronectin testing

Fetal fibronectin testing can also be used as a possible predictor of preterm labor for women who may be at risk. This test is done like a Pap smear, and test results are used to predict your risk of preterm labor. The fetal fibronectin test can't tell for sure if you're in preterm labor, but it can tell you if you're not. A woman at risk for premature delivery can be forewarned about what to do if preterm labor symptoms occur, and can undergo further screening tests.

Fetal distress - BabyCentre UK

In this article

- What is fetal distress?

- What causes fetal distress?

- How can I tell if my baby's distressed during pregnancy?

- What happens if my baby is distressed during pregnancy?

- What are the signs that my baby is distressed during labour?

- What happens if my baby is distressed during labour and birth?

- How will being distressed affect my baby?

- My baby had fetal distress.

Was it something I did?

Was it something I did?

What is fetal distress?

When your doctor or midwife sees signs that your baby is unwell during pregnancy, or isn't coping well with the demands of labour, they may call it fetal distress.

Fetal distress during labour and birth is fairly common. About a quarter of babies show signs of distress at some point (NHS Digital 2018).

During pregnancy, your baby's movements are a good way for you to get an idea of her wellbeing. If you notice your baby is moving less, or has a different pattern of movements, call your midwife or maternity unit straight away (NHS 2018, RCOG 2019).

What causes fetal distress?

There are many and varied reasons why a baby may become distressed.

It's often the case that a health complication has affected how much blood, with its essential oxygen and nutrients, reaches the baby via the placenta.

If you're expecting twins or more, one or both of your babies are more likely to become distressed.

Your baby may be more prone to distress if she’s small for her dates (Payne 2016).

If you're 35 or older, or are overdue, your baby may be more likely to become distressed (Payne 2016).

Your health before you became pregnant may be cause for your midwife or doctor to give your baby extra monitoring. For example, if you are obese, or if you have any of the following health conditions:

- diabetes

- asthma

- high blood pressure

- an under-active thyroid (hypothyroidism) (Payne 2016)

Certain complications that happen during pregnancy may make fetal distress more likely, including:

- Developing pre-eclampsia, which affects how well the placenta works.

- Having too much amniotic fluid, or too little amniotic fluid.

- Developing high blood pressure during pregnancy (gestational hypertension).

- Experiencing vaginal bleeding from week 24 onwards (Payne 2016).

Close to or during labour, some interventions may make your baby more prone to distress. For example, if your baby is breech and your midwife or doctor try to turn her with external cephalic version (Kuppens et al 2017). Speeding up your labour, which can make contractions stronger and more frequent, could also affect how well your baby copes (Boie et al 2018, NCCWCH 2014).

For example, if your baby is breech and your midwife or doctor try to turn her with external cephalic version (Kuppens et al 2017). Speeding up your labour, which can make contractions stronger and more frequent, could also affect how well your baby copes (Boie et al 2018, NCCWCH 2014).

The list of reasons why a baby can become distressed may seem like a long and overwhelming one. It reflects that every pregnancy and birth is different, and many factors come into play that result in a mum and baby needing extra care during pregnancy, labour and birth.

How can I tell if my baby's distressed during pregnancy?

Keep paying attention to your baby's movements. If you notice a change in your baby's normal pattern of movements, it may be a sign that she needs help (RCOG 2011, 2019). Call your midwife or maternity unit straight away if you notice anything different, of if you're at all concerned.

The type of movements you feel may change as you approach your due date, but the frequency should remain the same (RCOG 2011, 2019). Even though your baby has less room to move around in your womb, you should still continue to feel strong, frequent and regular movements (RCOG 2011).

Even though your baby has less room to move around in your womb, you should still continue to feel strong, frequent and regular movements (RCOG 2011).

There is no recommended set number of movements that you should look out for (NHS 2018, RCOG 2011, 2019). It's more a case of getting used to what’s normal for your baby (NHS 2018, RCOG 2019).

What happens if my baby is distressed during pregnancy?

If there are concerns for your baby, for example, if your bump seems small for your dates, your midwife will offer you an ultrasound scan. The scan can check how your baby is growing, and how much amniotic fluid surrounds her (RCOG 2011, 2019).

Otherwise, your midwife's investigations will revolve around your stage of pregnancy:

- If you’re less than 24 weeks pregnant and have never felt your baby move, your midwife will check for your baby’s heartbeat. She may also arrange an ultrasound scan to check your baby’s wellbeing.

- If you’re between 24 weeks and 28 weeks pregnant, and your baby’s movements have changed, your midwife will give you a full check-up, including checking your baby’s heartbeat, measuring your blood pressure, testing your urine and checking your baby’s growth.

- If you’re over 28 weeks pregnant, your midwife will do all of the above, as well as continuous monitoring of your baby’s heartbeat for at least 20 minutes using sensors attached to belts placed around your bump (RCOG 2011, 2019).

If your baby’s heart rate is normal, but you are still not feeling your baby move regularly, your midwife or doctor is likely to offer you regular Doppler scans. This will help her to monitor the flow of blood from your placenta to your baby (RCOG 2011, 2013, 2019, Signore and Spong 2018).

Depending on how far along you are in your pregnancy, your doctor may recommend that it’s safer for your baby to be born sooner, rather than later (RCOG 2013b, 2019). You may need to have an induction of your labour, or to give birth by caesarean (Payne 2016).

You may need to have an induction of your labour, or to give birth by caesarean (Payne 2016).

Any kind of a scare during pregnancy is bound to be frightening. It may reassure you to know that most women who notice a one-off change in their baby’s movements go on to have straightforward pregnancies and healthy babies (RCOG 2011, 2019).

What are the signs that my baby is distressed during labour?

One of the first signs may be your baby's poo (meconium) showing in your waters when they break. Your midwife will check for meconium-stained waters (NCCWCH 2014). Using a maternity pad will help to show up the colour.

Amniotic fluid is usually clear, with a hint of pink, yellow or red. But if it's black, this is a sign that your baby has passed meconium (Newson 2015a). If you’re overdue, meconium in your waters may be more likely (Newson 2015a, Shaikh et al 2010).

Meconium alone doesn't always mean there's a problem (NCCWCH 2014, Newson 2015a, Reed 2015). If your baby has a raised heart rate, along with meconium, this is a sign of distress (Reed 2015).

If your baby has a raised heart rate, along with meconium, this is a sign of distress (Reed 2015).

The thickness of the meconium is important. Lumpy meconium is a concern, because it can cause problems if it gets into your baby's airways (Newson 2015a, b, NCCWCH 2014, NICE 2014).

If your midwife sees lumps in your waters, she will arrange for you to move to an obstetric-led unit, if you aren't already in one. You'll be able to have more careful monitoring, with the right specialists on stand-by (NCCWCH 2014, NICE 2014).

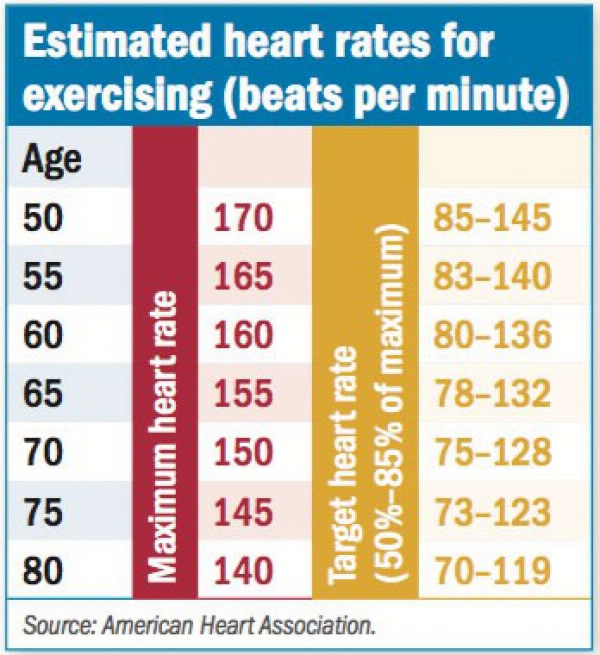

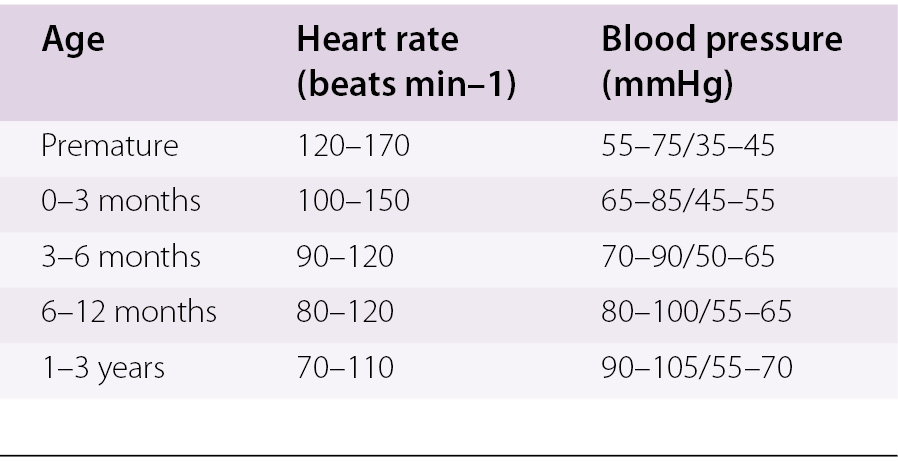

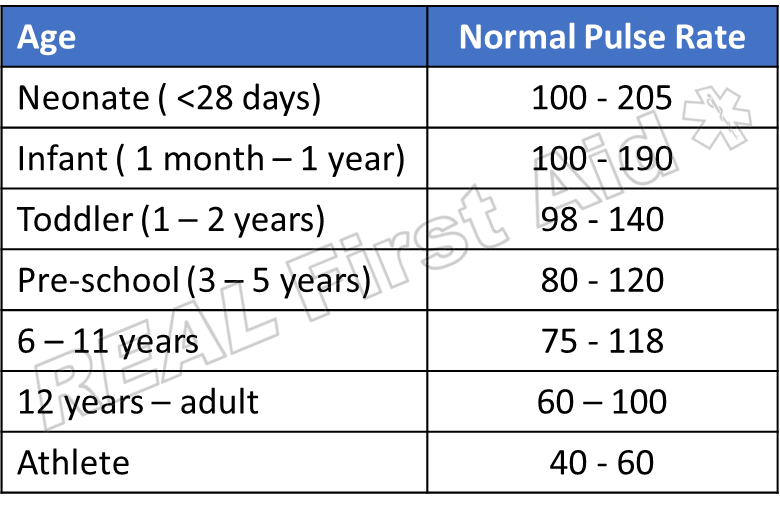

As a matter of course, your midwife will monitor your baby's heart rate to check how she’s doing. If changes occur in your baby's heart rate, it can be a sign that she’s becoming distressed. The normal range of a full-term baby's heart rate is between 110 beats and 160 beats per minute (bpm) (NCCWCH 2014, Payne 2015).

There are two main methods of monitoring your baby:

- Intermittently (at intervals), also called intermittent auscultation.

- Continuously, also called continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) and sometimes shortened to cardiotocography (CTG) (NCCWCH 2014).

Intermittent monitoring

Your midwife will place a hand-held Doppler ultrasound (Sonicaid) or ear trumpet (Pinard stethoscope) on your belly (NCCWCH 2014).

During the first stage of your labour, your midwife will monitor your baby at least every 15 minutes, after each contraction (NCCWCH 2014). During the pushing stage, she'll monitor your baby at least every five minutes, after each contraction (NCCWCH 2014).

Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM)

EFM is recommended if you have certain complications before labour starts, such as gestational diabetes or if you’re expecting a small baby (RCOG 2013a, b). It's also used when complications happen in labour, such as very high blood pressure or infection (NCCWCH 2014). Or when you have certain interventions, such as an epidural or a drip to speed up labour (NCCWCH 2014).

EFM involves two sensors being placed on your belly. One sensor monitors your contractions, and the other monitors your baby's heartbeat.

Your doctor or midwife may also place a small clip, called a fetal scalp electrode (FSE), on your baby's head, to get an even more accurate reading of your baby's heartbeat. They will only try an FSE after your waters have broken.

Although a low or high heart rate may be cause for concern, your midwife or doctor will look for other signs to help decide whether there really is a problem, such as:

- a lack of change in your baby's heartbeat (variability)

- a drop (deceleration) in the heartbeat following a contraction

- your baby taking time to recover from each contraction (NCCWCH 2014, Payne 2015).

A faster heart rate (tachycardia) could also happen if you have a fever (NCCWCH 2014). A slower heart rate (bradycardia) during contractions could be caused by your position, such as lying on your back. Your midwife may ask you to change position or to get up and move around while you are in labour (NCCWCH 2014).

Your midwife may ask you to change position or to get up and move around while you are in labour (NCCWCH 2014).

A drop in your baby's heart rate may be nothing to worry about. For example, your baby may be having a sleep, or a bit of a rest (NCCWCH 2014).

What's involved in an assisted birth?

Find out what happens when your baby needs help to be bornMore labour and birth videos

What happens if my baby is distressed during labour and birth?

Sometimes, there are clear signs from EFM alone that your baby is in distress, and doing further tests wouldn't be in your baby's best interests (NCCWCH 2014). If there is any uncertainty, your doctor should make absolutely sure before recommending further action (NCCWCH 2011, 2014).

If your midwife or doctor suspects that your baby is distressed, she may touch your baby's scalp to see if your baby responds to the stimulation (Macones 2019, NCCWCH 2014). She may also take a tiny sample of blood from your baby's scalp (a fetal blood sample).

The blood sample will be tested to see if your baby is getting enough oxygen (NCCWCH 2011, 2014). This is the best indicator of how your baby is coping with labour (NCCWCH 2014).

To take a blood sample, your doctor will ask you to lie on your left side, before inserting a small tube into your vagina (NCCWCH 2014, Payne 2015). Your doctor will spray your baby's head with a local anaesthetic through the tube, and will then carefully insert a small needle to take the sample from your baby's head. This shouldn't hurt your baby at all.

A blob of blood will appear on your baby's scalp. Your doctor will capture the blood in a tiny glass tube. The amount of oxygen in the blood sample shows how your baby is coping with labour. It also gives a picture of her energy reserves, and how much longer she may be able to cope with the rigours of labour.

If the sample is well-oxygenated, your labour is likely to carry on as it is. If oxygen levels are at a lower level than they should be, your doctor may carry out the test again (Payne 2015).

If all the checks suggest your baby is in distress, your midwife or doctor will try to help her by:

- Increasing your fluid levels by offering you a drink or via a drip.

- Offering you paracetamol if you have a raised temperature.

- Lying you down on your left-hand side to reduce the pressure of your womb on a major vein in your body (vena cava). This prevents reduced blood flow to the placenta and your baby.

- Temporarily stopping any medications you've been given, to increase your contractions (NCCWCH 2014).

If your baby is still showing signs of distress, despite these efforts, your baby will need to be born as soon as possible (NCCWCH 2014, Payne 2015).

You may feel as though events are spinning out of control at this point. Your doctor or midwife should clearly explain to you and your birth partner what's happening, and why.

How your baby is born depends partly on what stage of labour you’ve reached, and if your cervix is fully dilated. Your baby may need to be born vaginally, with the help of a vacuum-cap on her head (ventouse), or with forceps (NCCWCH 2014).

Your baby may need to be born vaginally, with the help of a vacuum-cap on her head (ventouse), or with forceps (NCCWCH 2014).

If neither of these types of assisted birth is suitable, your baby may need to be born by caesarean section (NCCWCH 2014).

By this stage, you may feel relieved that your labour will be over soon, or overwhelmed by the speed at which you're rushed to theatre. Your doctors and midwives are working fast to make sure that you and your baby stay well.

How will being distressed affect my baby?

It depends on what's made your baby distressed in the first place, and the level of distress she experiences as a result. There's a big range, because every baby and birth is different, and there are many causes of fetal distress.

It's possible that, despite giving off distress signals during labour, your baby arrives well and healthy and flies through her newborn checks (Miller 2018). If that's the case, she won't need any treatment and you can both go to the postnatal ward before you go home.

However, fetal distress can be a sign of a serious problem for some babies, A severe problem with the placenta (MBRRACE-UK 2018, Payne 2016) or an undiagnosed abnormality (MacLennan et al 2015) count as severe problems.

Some babies may have a lasting condition, such as a neurological disorder, that makes the stress of labour very hard to copy with (Miller 2018). Other babies may become distressed because they are being born too early, or too small (MBRRACE-UK 2018).

Specialist nurses and doctors will be on standby to help your baby immediately after the birth if she has shown signs of distress, or is known to be small for dates, or arriving prematurely. Your neonatal medical team can act quickly to give your baby the best support and treatment (NCCWCH 2011, NICE, 2015, RCOG 2014).

If there has been meconium in your waters, treatment for your baby will depend on whether she has breathed it in or not. If your baby has inhaled it, there's a small risk that her airways may be affected. This is called meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS).

This is called meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS).

MAS may:

- Irritate your baby's lung tissue.

- Cause inflammation and blood pressure problems in your baby's lungs.

- Block your baby's airways (Newson 2015b).

If your midwife or doctor has seen thick or lumpy meconium during labour, they will check your baby's heartbeat, breathing, temperature, and skin colour straight after the birth. If these are not normal, your doctor will start treatment with gentle suction to clear your baby's airways (Newson 2015b, NICE 2014).

If your baby appears to have breathing problems she will be admitted to the neonatal unit (Newson 2015a). Most babies improve with treatment and recover completely from MAS (Newson 2015b).

If there were signs of meconium, but your baby didn't seem to breathe any in, your doctor or midwife will still check her carefully for signs of breathing problems (Newson 2015a, NICE 2014).

My baby had fetal distress.

Was it something I did?

Was it something I did?It's unlikely that you could have done anything to prevent your baby from becoming distressed. It's natural to feel upset about it, and you may find it hard to come to terms with, just when you're adjusting to new parenthood.

Fetal distress can happen for all sorts of reasons, many of them beyond your control. It may help to talk about your feelings with your midwife or a counsellor after your baby is born. You can ask your midwife if there's a birth reflections service at your maternity unit.

Read more about recovering emotionally from a difficult birth.

References

Boie S, Glavind J, Velu AV, et al. 2018. Discontinuation of intravenous oxytocin in the active phase of induced labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8):CD012274. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]<

Kuppens SM, Smailbegovic I, Houterman S, et al. 2017. Fetal heart rate abnormalities during and after external cephalic version: which foetuses are at risk and how are they delivered? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1): 363. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed September 2019]

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed September 2019]

Macones G. 2019. Management of intrapartum category I, II, and III fetal heart rate tracings. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com [Accessed July 2019]

MBRRACE-UK. 2018. Cerebral palsy: causes, pathways, and the role of genetic variants. Perinatal mortality surveillance report: UK perinatal deaths for births January to December 2016. Mothers and Babies: Reducing the Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK. www.npeu.ox.ac.uk [Accessed September 2019]

Miller DA. 2018. Intrapartum fetal heart rate assessment. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com [Accessed September 2019]

NCCWCH. 2011. Caesarean section. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, NICE Clinical guideline. www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

NCCWCH. 2014. Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, Clinical guideline, 190.![]() www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

NCCWCH. 2015. Preterm labour and birth. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, NICE guideline, 25. www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

Newson L. 2015a. Meconium-stained liquor. Patient. patient.info [Accessed September 2019]

Newson L. 2015b. Meconium aspiration. Patient. patient.info [Accessed September 2019]

NHS Digital. 2018. NHS maternity statistics, 2017-18: HES NHS maternity statistics tables. NHS Materntiy Statistics, England 2017-18. digital.nhs.uk [Accessed September 2019]

NHS. 2018. Your baby's movements. NHS, Health A-Z, pregnancy and baby. www.nhs.uk [Accessed September 2019]

NICE. 2014. Information for the public: intrapartum care for healthy women and babies - if there is meconium during labour. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

Payne J. 2015. Intrapartum fetal monitoring. Patient. patient.info [Accessed September 2019]

Patient. patient.info [Accessed September 2019]

Payne J. 2016. Fetal Distress. Patient. patient.info [Accessed September 2019]

Reed R. 2015. The curse of meconium stained liquor. Midwife Thinking. midwifethinking.com [Accessed September 2019]

RCOG. 2011. Reduced fetal movements. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Green-top guideline, 57. www.rcog.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

RCOG. 2013a. Information for you: gestational diabetes. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

RCOG. 2013b. The investigation and management of the small-for-gestational-age fetus. 2nd edition, minor revisions January 2014. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Green-top Guideline No. 31. www.rcog.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

RCOG. 2014. Information for you: having a small baby. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org. uk [Accessed September 2019]

uk [Accessed September 2019]

RCOG. 2019. Information for you: your baby's movements in pregnancy. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. www.rcog.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

Shaikh EM, Mehmood S, Shaikh MA. 2010. Neonatal outcome in meconium stained amniotic fluid - one year experience. J Pak Med Assoc 60(9): 711-4. jpma.org.pk [Accessed September 2019]

Signore C, Spong C. 2018. Overview of antepartum fetal surveillance. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com [Accessed September 2019]

Show references Hide references

Hypotension in children: Childhood hypertension

The problem of arterial hypotension (low blood pressure) in children has become more common than before. Evidence suggests that hypotonic conditions are even more common in children than in adults. Unfortunately, this problem also applies to newborns.

For a child, blood pressure is considered low, the upper limit of which is no more than 100, and the lower limit is no more than 60. The risk group is schoolchildren, among whom girls are more susceptible to this condition.

The risk group is schoolchildren, among whom girls are more susceptible to this condition.

But the pressure in children can be not only low, but also high. In this case, it is customary to speak of hypertension. Arterial hypertension, hypertension in children - a persistent increase in blood pressure above the 95th centile of the scale for the distribution of blood pressure values for a particular age, sex, weight and body length of the child. Normal blood pressure is considered to be the values of systolic and diastolic blood pressure that do not go beyond the 10th and 90th centiles.

Causes

It is not always possible to find pathological causes of persistent low blood pressure. This usually happens with primary hypotension, which, however, has its own causes:

- asthenic constitution;

- puberty;

- hereditary predisposition;

- problems during pregnancy and childbirth;

- features in the character of the child, for example, a tendency to depression;

- overwork;

- stress.

Secondary hypertension has causes that are associated with diseases of internal organs and systems: kidney disease, pneumonia, cardiovascular disease, adrenal disease, etc. Also, this form of hypotension can develop due to the intake of certain drugs, especially when you consider that the child's body is most sensitive to drugs.

But a child's blood pressure may rise for various reasons. This may depend on hereditary, external factors, specific age. If a pregnant woman smokes during pregnancy, the risk that the nursing baby will have health problems increases.

Diseases of the endocrine system also cause hypertension. Children with VVD are considered potential hypertensive patients.

An overdose of some nasal drops leads to vasoconstriction not only of the nose, but even of the arteries. Because of this, the pressure rises.

It is noted that high blood pressure is often inherent in those children who are obese or overweight.

Unhealthy diet, low physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, stress, workload at school. All of these can cause health problems.

All of these can cause health problems.

Symptoms

If hypotension is manifested in a newborn, then the parents do not have any special problems, because it is difficult to determine from his condition that there are health problems. This is explained by the fact that the child sleeps a lot, rarely cries, is in constant calm.

Children with reduced muscle tone, legs and arms can extend more than 180 degrees at the joints. In addition, the following symptoms are observed: a delay in the rate of motor development and a violation of swallowing and sucking.

There may also be dizziness, fainting, nosebleeds, emotional lability, decreased performance, joint and muscle pain, sudden deterioration in well-being, headache.

If the pressure rises slightly, the child may feel well. Although the child can quickly get tired, irritated. But if the pressure rises strongly, the child will always feel bad. Among his complaints are the following: headache, dizziness, pain in the heart, palpitations, memory impairment.

If a hypertensive crisis occurs. There may be symptoms such as a sharp headache, nausea, blurred vision, convulsions, impaired consciousness, and others.

Diagnosis

First of all, blood pressure measurements are required to make a diagnosis. This is usually done in a sitting position in the first half. The measurement takes place three times, the interval between these is three minutes. Also, it is not done immediately after mental or physical exertion, but after an hour has passed.

In addition, the following diagnostic methods are used: ECG, ECHO-kg, ABPM, study of autonomic homeostasis, EEG registration, psychological testing, clinical and biochemical blood tests, consultation of the necessary specialists in order to exclude secondary arterial hypotension.

To confirm the diagnosis of arterial hypertension, daily monitoring and tests with different types of loads are used.

In the course of the study, it is important to identify the cause of the increase in pressure if hypertension is secondary. This is what helps the doctor prescribe effective treatment. If the cause of hypertension is not eliminated, therapeutic measures will not give the desired effect, the result will be temporary.

This is what helps the doctor prescribe effective treatment. If the cause of hypertension is not eliminated, therapeutic measures will not give the desired effect, the result will be temporary.

Treatment

Treatment may be drug or non-drug. If arterial hypotension occurs in a labile form, then preference is given to the second type of treatment, which includes several methods.

It is necessary to normalize the daily routine, which includes the correct combination of study and rest for the child. It is important to take timely breaks. This also includes quality sleep at night, as well as daytime rest.

Don't forget your daily walks. On the day in the fresh air, the child should be about two hours.

Meals should be taken four to six times a day. At the same time, there should be a sufficient amount of salt in the food. It is important that the products contain a sufficient amount of useful substances and trace elements, which are very important for the child's body. It is important to maintain optimal water regime.

It is important to maintain optimal water regime.

Massage has a good effect. Recommended area: hands, collar area and calf muscles.

If these methods are not sufficient, or if the child's hypotension has progressed to a more serious method, the doctor will prescribe the necessary medications.

Treatment of hypertension depends on many factors. If arterial hypertension in children and adolescents is accompanied by a slight increase in pressure, non-drug therapy is used.

If the child is overweight, it is necessary to reduce the body weight. This is achieved by increasing physical activity and normalizing nutrition.

If the school sets a lot of homework, it is necessary to make sure that this does not affect the health and condition of the student.

If lifestyle changes do not lower blood pressure or if blood pressure is high, drug treatment is given. Antihypertensive therapy is also prescribed for those children who suffer from diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney diseases. Most of the drugs that are prescribed for adults are also used for younger patients. But doses and drugs are always selected individually.

Most of the drugs that are prescribed for adults are also used for younger patients. But doses and drugs are always selected individually.

Why low heart rate: causes of heart rate decrease, treatment

- Physiological and pathological bradycardia

- What happens in the body when the pulse slows down

- Varieties of

- Why different types of bradycardia develop

- Low pulse in children: causes and consequences

- Low pulse symptoms

- Diagnostics

- What to do if the pulse is low

- Surgical treatment

Image by Freepik

A condition in which the heart rate slows down is called bradycardia. They talk about it if the frequency of beats per minute is reduced to 60 or less. In some cases, this is due to physiological reasons, but most often a low pulse occurs in people with various pathologies. Heart rate (heart rate) decreases with cardiac diseases, poisoning, diseases of the central nervous system, an overdose of certain drugs.

Physiological and pathological bradycardia

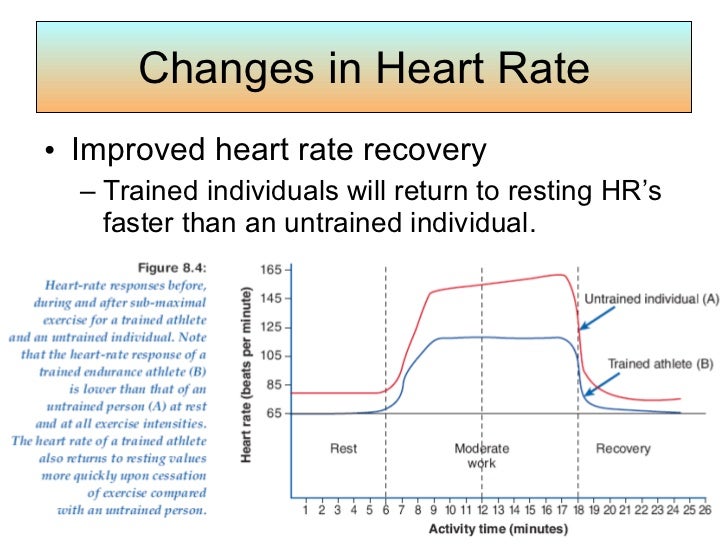

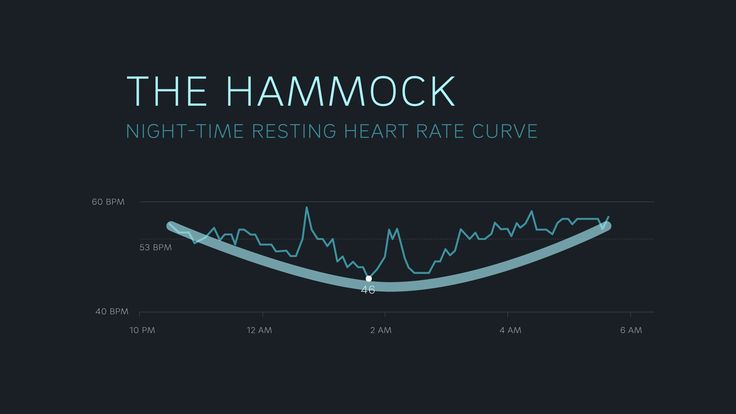

Low heart rate as a physiological phenomenon is typical for professional athletes. Due to constant intense training, the body gets used to increased loads, which affects the autonomic regulation. The heart rate naturally slows down in a sleeping person. When the body is at rest, the pulse becomes low and blood pressure decreases. This is the norm. After waking up, when a person begins to engage in vigorous activity, the pulse rate rises.

If there is a slowing of the heart rate during wakefulness for unknown reasons, this condition requires the attention of specialists. Most often it is caused by diseases of the cardiovascular or nervous system, endocrine disorders, injuries. Low heart rate occurs in both adults and children.

What happens in the body when the pulse slows down

Heart rate decreases due to improper operation of the sinus node. He is responsible for the production of electrical impulses, due to which the heart contracts at a physiological frequency. If there is a malfunction in the sinus node, the signals along the conduction paths are distributed incorrectly. This primarily concerns the conduction of electrical impulses between the sinus node and the components of the heart muscle.

If there is a malfunction in the sinus node, the signals along the conduction paths are distributed incorrectly. This primarily concerns the conduction of electrical impulses between the sinus node and the components of the heart muscle.

With a moderately low pulse, a person does not notice a pronounced deterioration in well-being. If the heart rate slows down further, negative symptoms appear. They are caused by impaired blood supply to tissues. Together with blood, nutrients and oxygen enter the tissues, therefore, with a prolonged state of low pulse, a person develops oxygen starvation. Oxygen starvation is manifested by weakness, lethargy, and other signs of deterioration in well-being.

A pulse less than 40 beats indicates severe bradycardia. This condition is dangerous for the body due to severe circulatory disorders. The patient is shown taking medication, but in severe cases, drug therapy is not enough, therefore, an operation is performed to install a pacemaker.

Varieties

A low heart rate can be acute or chronic. The classification of bradycardia, depending on the cause, includes four types of the disease:

-

neurogenic;

-

organic;

-

medical;

-

toxic.

Sometimes doctors do not have an exact answer to the question of why a person has a low pulse. In this case, we are talking about idiopathic bradycardia - a disease of unknown etiology. Pathologies are susceptible to persons of mature and old age. Experts believe that low heart rate may be associated with the physiological processes of aging.

Why different types of bradycardia develop

-

Diseases of the central nervous system. A decrease in heart rate often occurs in patients with VSD (vegetovascular dystonia), increased intracranial pressure, neoplasms and brain contusions. People with such diseases suffer from chronic neurogenic bradycardia.

It also occurs against the background of neurosis with vegetative disorders. If a person wears clothes that squeeze the neck, the work of the carotid sinus is disrupted and the pulse slows down.

It also occurs against the background of neurosis with vegetative disorders. If a person wears clothes that squeeze the neck, the work of the carotid sinus is disrupted and the pulse slows down. -

Endocrine pathologies, diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. People with stomach and duodenal ulcers often suffer from a slow pulse. With a decrease in the production of thyroid hormones, metabolic processes are disturbed, and the heart rate decreases. With the development of myxedema, which is expressed by an acute shortage of thyroid hormones, bradycardia worsens and begins to threaten a person's life. The same happens with diabetic ketoacidosis, a decrease in the production of adrenaline by the adrenal glands.

-

Cardiological pathologies. Bradycardia is a type of arrhythmia and is most often associated with heart disease. A low pulse is one of the symptoms of a heart attack or inflammation of the myocardium, cardiosclerosis, and a number of other pathologies.

The reason is changes in the tissues of the sinus node and myocardium. The process of generating electrical impulses is disturbed, tissue conductivity worsens. The most severe complication is a dysfunction of automatism, in which the production of impulses stops. If the pathology affects the myocardium, the production of impulses is preserved, but there are difficulties with their transmission to the ventricles. Only a certain proportion of signals reaches the target, so the heart rate becomes slow.

The reason is changes in the tissues of the sinus node and myocardium. The process of generating electrical impulses is disturbed, tissue conductivity worsens. The most severe complication is a dysfunction of automatism, in which the production of impulses stops. If the pathology affects the myocardium, the production of impulses is preserved, but there are difficulties with their transmission to the ventricles. Only a certain proportion of signals reaches the target, so the heart rate becomes slow. -

Incorrect medication. Some drugs cause drug-induced bradycardia. It leads to an incorrectly selected dosage or hypersensitivity to the components of cardiac glycosides, antiarrhythmia drugs, adrenergic blockers, morphine-based drugs.

-

Poisoning, intoxication in diseases. Slow heart rate occurs in people with impaired water and electrolyte balance, as well as with severe infectious lesions of the body. In severe forms of hepatitis, liver failure develops and, as a result, intoxication.

The same happens with sepsis, typhoid fever. Heart rate slows down with excessive intake of calcium and potassium, poisoning with organophosphorus substances.

The same happens with sepsis, typhoid fever. Heart rate slows down with excessive intake of calcium and potassium, poisoning with organophosphorus substances.

Low pulse in children: causes and consequences

A pulse below normal is detected in approximately 3.5% of children. As a rule, the pathology is caused by congenital heart defects or insufficiency of the sinus node. In children without heart disease, disorders may occur due to a bacterial or viral infection. Pathogenic microbes secrete waste products that cause a response from the immune system and disrupt the heart.

Some people have a low heart rate from birth, and this becomes apparent at an early age. This phenomenon is called constitutional-familial bradycardia, which is hereditary.

In children and adolescents, the development of various types of arrhythmia can be triggered by excessive psycho-emotional stress, unfavorable family conditions.

Low pulse symptoms

With a slight reduction in heart rate, the disease is asymptomatic and is detected by measuring the pulse. More pronounced bradycardia manifests itself as symptoms of circulatory disorders:

More pronounced bradycardia manifests itself as symptoms of circulatory disorders:

-

weakness, fatigue, dizziness;

-

pallor and bluish tint of the skin;

-

slowing down of intellectual and physical development in childhood;

-

irritability;

-

excessive sweating;

-

fainting state;

-

decrease in blood pressure;

-

pain in the chest.

With a critical decrease in heart rate, the patient requires emergency medical care.

Diagnostics

With a low pulse, you need to contact a cardiologist and undergo a comprehensive examination:

-

laboratory blood and urine tests;

-

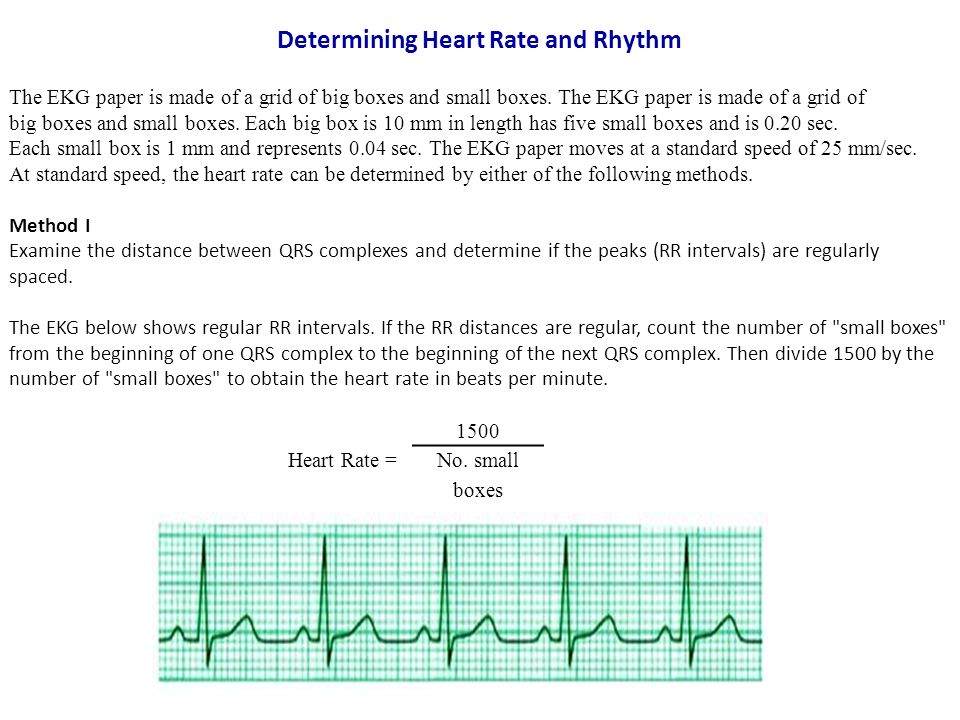

electrocardiography;

-

Holter monitoring;

-

Ultrasound of the heart;

-

load tests.

What to do if the pulse is low

To cure a reduced heart rate, you need to know exactly its cause. If the condition is caused by hormonal pathology or a violation of the water and electrolyte balance, therapy is selected after conducting the necessary tests for hormones and electrolytes. Taking medications makes up for the lack of necessary substances and thereby normalizes the heart rhythm.

If bradycardia is due to drug overdose, other drugs should be selected or daily doses should be reduced.

Low pulse during intoxication is a side effect caused by the underlying disease, so it is necessary to treat it.

If the decrease in heart rate is due to cardiac pathology, the cardiologist selects the appropriate treatment for this clinical case. Even in the absence of symptoms, people with bradycardia need to undergo regular medical examinations, monitor changes in the work of the heart.

With a chronic decrease in heart rate, appoint:

Duration of admission is 3-6 months. The doctor selects a combination of drugs and controls the course of treatment. The composition of complex therapy may include herbal preparations that have a tonic effect. Basically, extracts of ginseng and eleutherococcus are prescribed - natural stimulants.

The doctor selects a combination of drugs and controls the course of treatment. The composition of complex therapy may include herbal preparations that have a tonic effect. Basically, extracts of ginseng and eleutherococcus are prescribed - natural stimulants.

In severe conditions, it is important to normalize the pulse rate as soon as possible to avoid tissue hypoxia. The patient is hospitalized and parenteral preparations are used to improve myocardial function.

Surgical treatment

The reason for surgical intervention for bradycardia is the serious condition of the patient, which has developed in connection with heart defects or acquired diseases. Operations are carried out for children and adults. Children with congenital pathologies are given epicardial stimulators or endocardial electrodes.

Young and older people are shown the installation of a pacemaker. It takes over the production of electrical impulses that are generated at a physiological frequency.