Uterus anatomy pregnancy

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - uterus | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content5-minute read

Listen

What does the uterus look like?

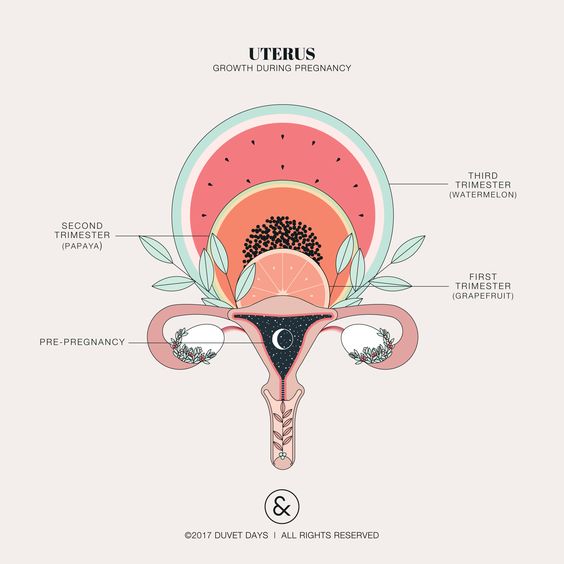

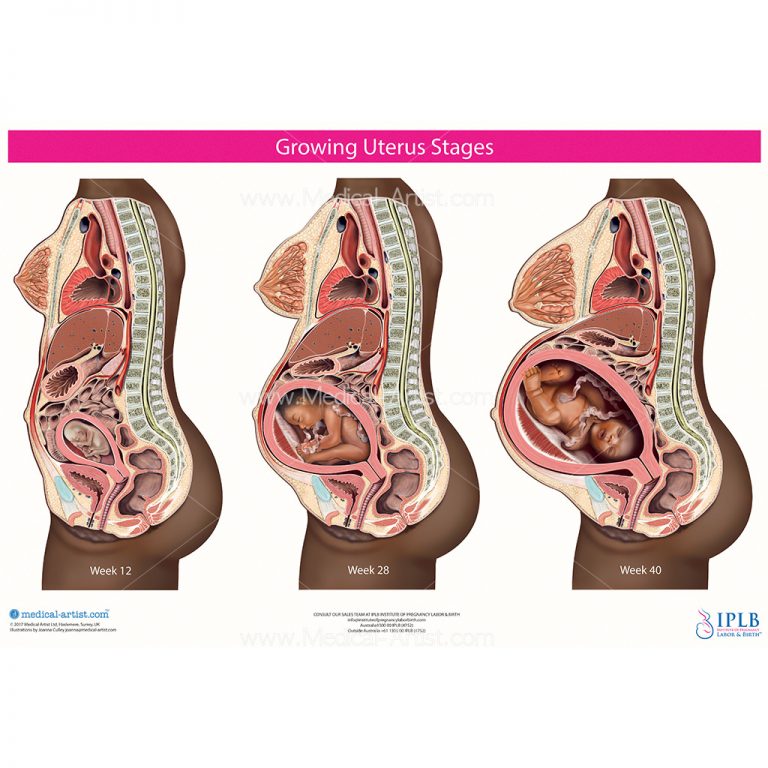

One of the most recognised changes in a pregnant woman’s body is the appearance of the ‘baby bump’, which forms to accommodate the baby growing in the uterus. The primary function of the uterus during pregnancy is to house and nurture your growing baby, so it is important to understand its structure and function, and what changes you can expect the uterus to undergo during pregnancy.

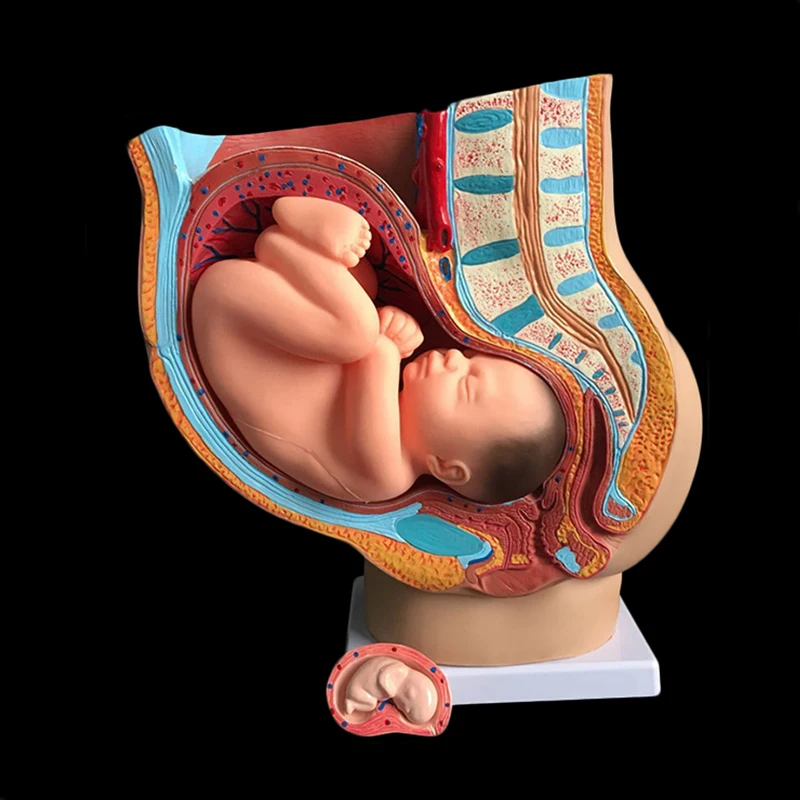

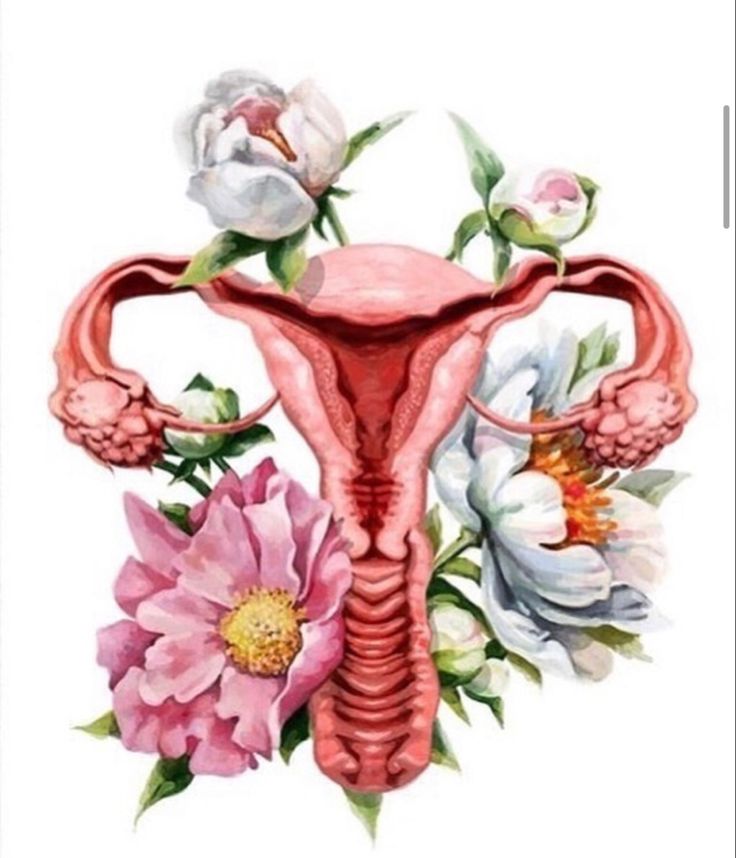

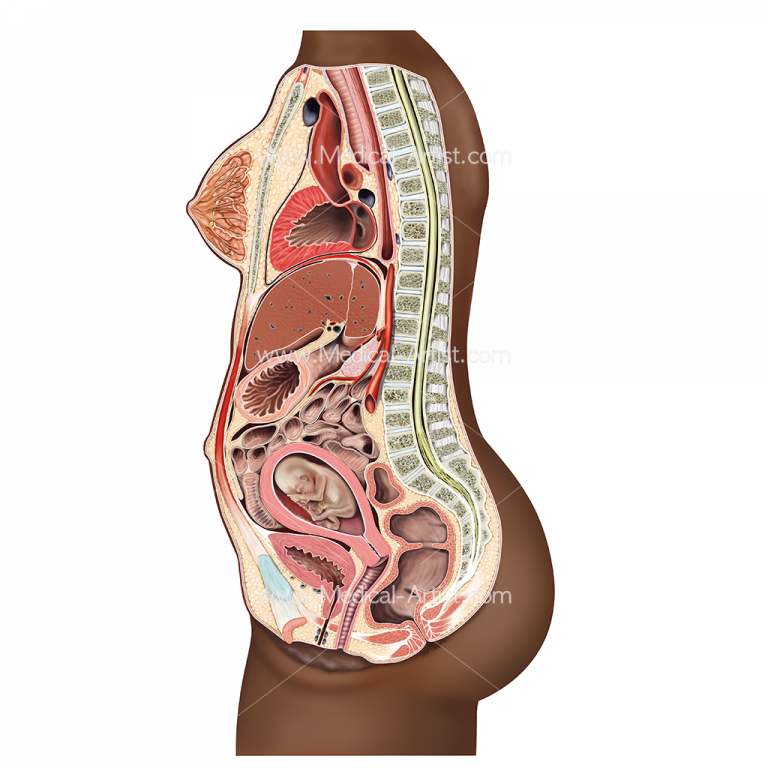

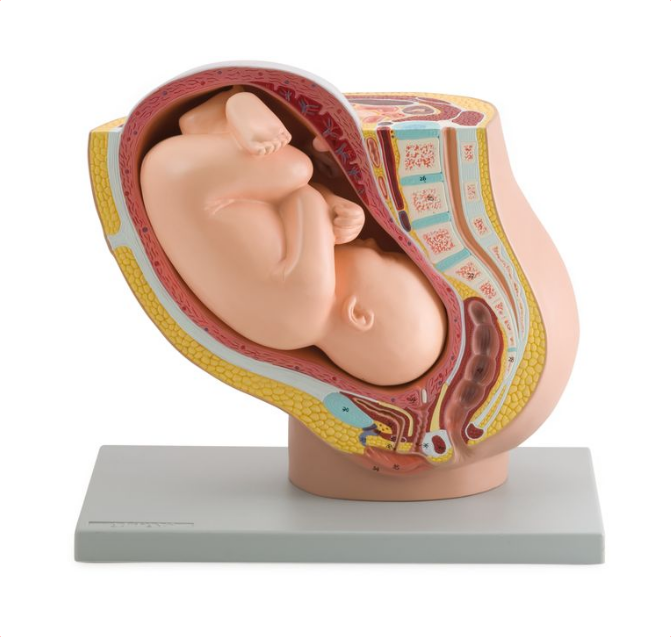

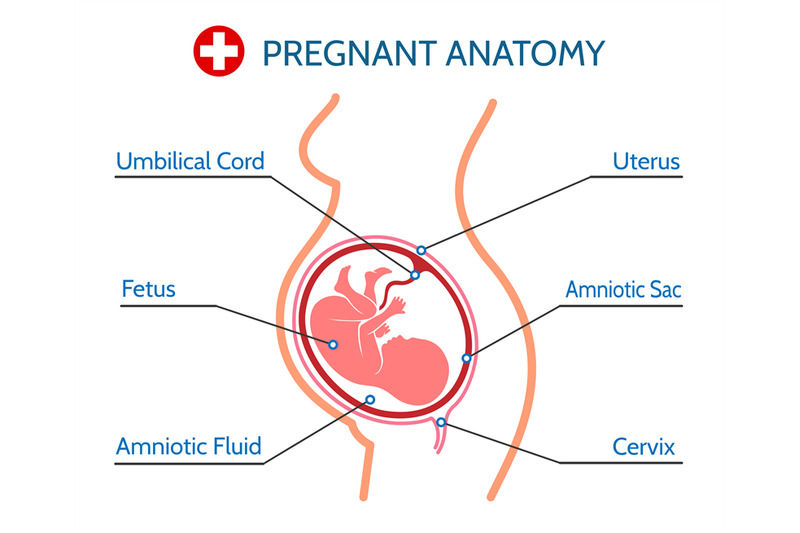

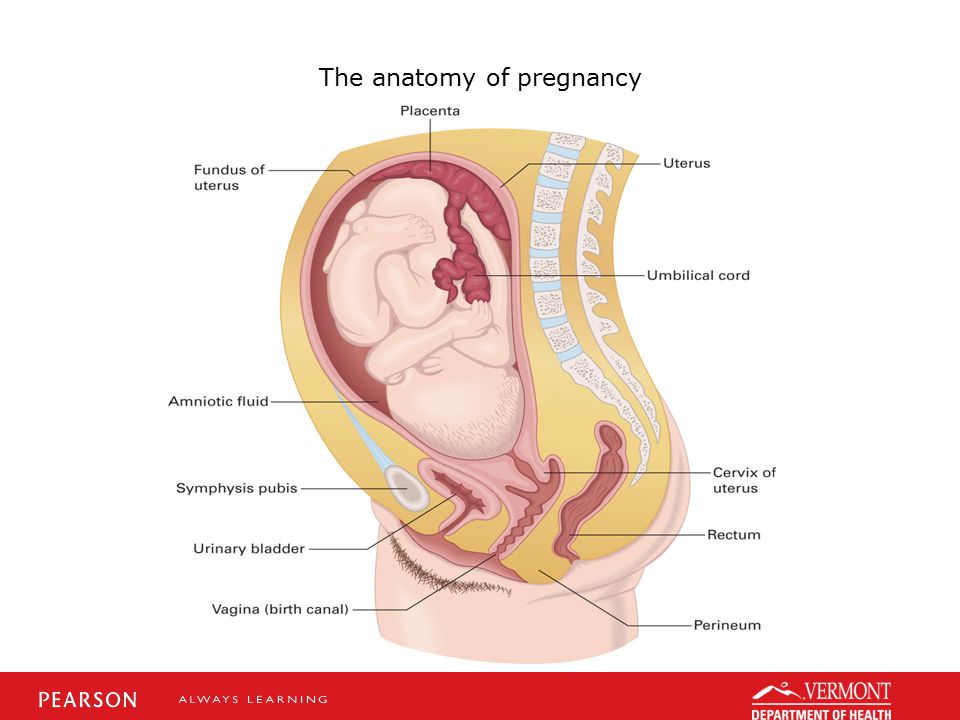

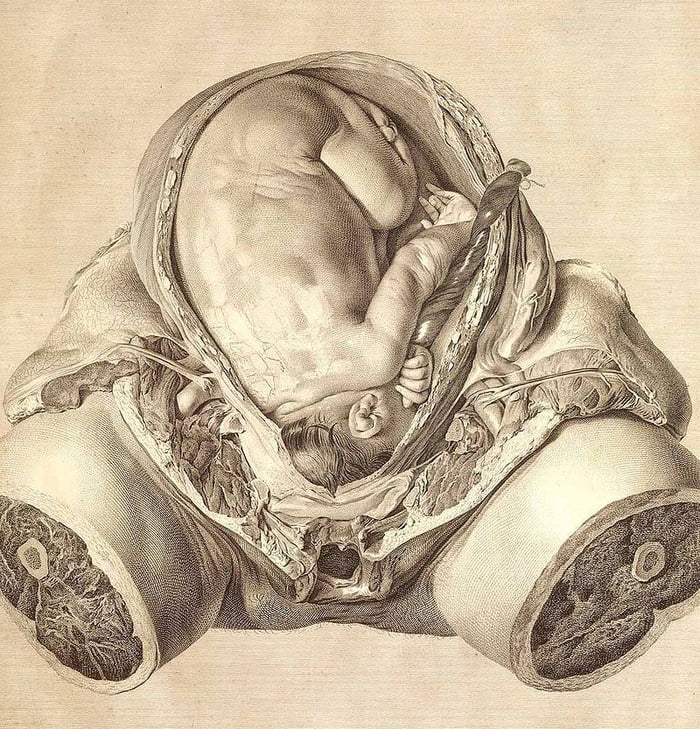

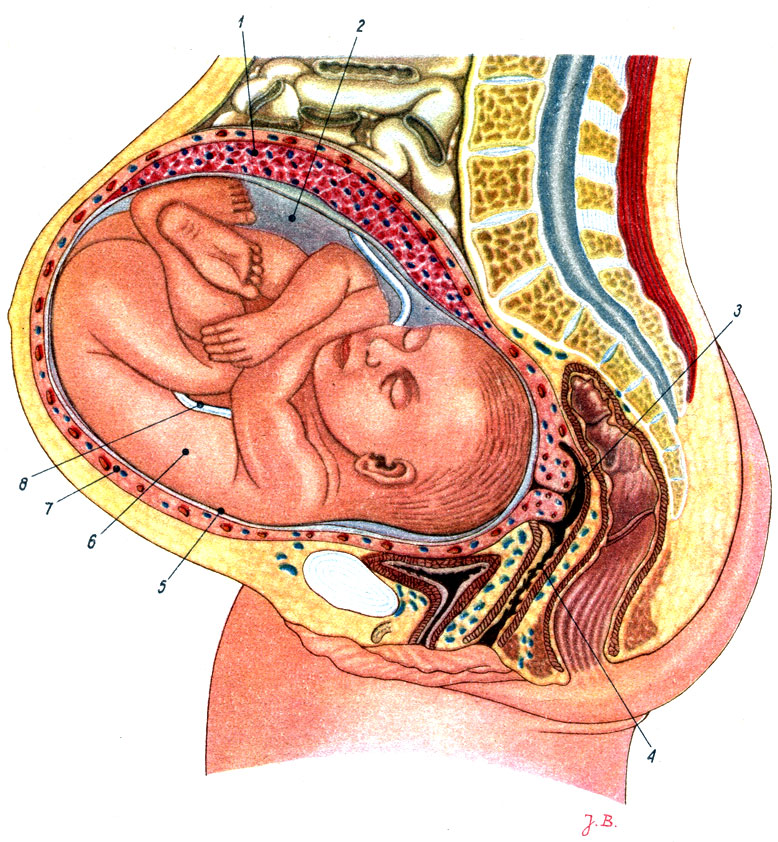

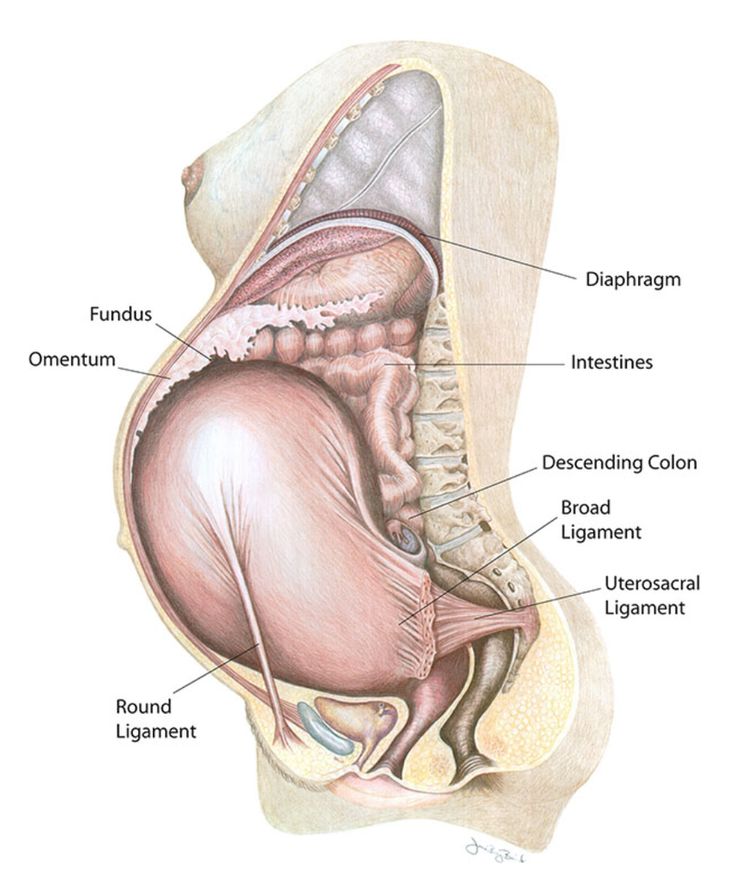

The uterus (also known as the ‘womb’) has a thick muscular wall and is pear shaped. It is made up of the fundus (at the top of the uterus), the main body (called the corpus), and the cervix (the lower part of the uterus ). Ligaments – which are tough, flexible tissue – hold it in position in the middle of the pelvis, behind the bladder, and in front of the rectum.

The uterus wall is made up of 3 layers. The inside is a thin layer called the endometrium, which responds to hormones – the shedding of this layer causes menstrual bleeding. The middle layer is a muscular wall. The outside layer of the uterus is a thin layer of cells.

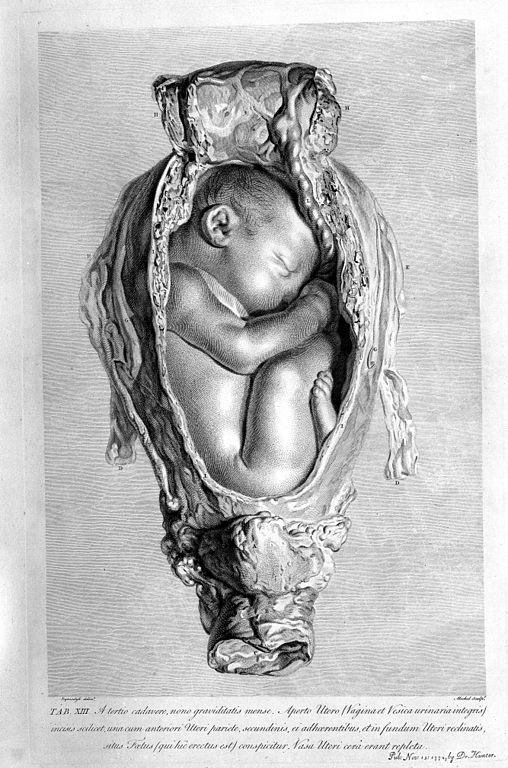

Illustration showing the female reproductive system.The size of a non-pregnant woman's uterus can vary. In a woman who has never been pregnant, the average length of the uterus is about 7 centimetres. This increases in size to approximately 9 centimetres in a woman who is not pregnant but has been pregnant before. The size and shape of the uterus can change with the number of pregnancies and with age.

How does the uterus change during pregnancy?

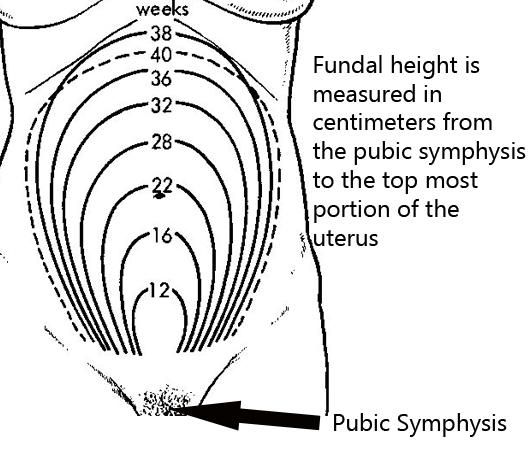

During pregnancy, as the baby grows, the size of a woman’s uterus will dramatically increase. One measure to estimate growth is the fundal height, the distance from the pubic bone to the top of the uterus. Your doctor (GP) or obstetrician or midwife will measure your fundal height at each antenatal visit from 24 weeks onwards. If there are concerns about your baby’s growth, your doctor or midwife may recommend using regular ultrasound to monitor the baby.

Your doctor (GP) or obstetrician or midwife will measure your fundal height at each antenatal visit from 24 weeks onwards. If there are concerns about your baby’s growth, your doctor or midwife may recommend using regular ultrasound to monitor the baby.

Fundal height can vary from person to person, and many factors can affect the size of a pregnant woman’s uterus. For instance, the fundal height may be different in women who are carrying more than one baby, who are overweight or obese, or who have certain medical conditions. A full bladder will also affect fundal height measurement, so it’s important to empty your bladder before each measurement. A smaller than expected fundal height could be a sign that the baby is growing slowly or that there is too little amniotic fluid. If so, this will be monitored carefully by your doctor. In contrast, a larger than expected fundal height could mean that the baby is larger than average and this may also need monitoring.

As the uterus grows, it can put pressure on the other organs of the pregnant woman's body. For instance, the uterus can press on the nearby bladder, increasing the need to urinate.

For instance, the uterus can press on the nearby bladder, increasing the need to urinate.

How does the uterus prepare for labour and birth?

Braxton Hicks contractions, also known as 'false labour' or 'practice contractions', prepare your uterus for the birth and may start as early as mid-way through your pregnancy, and continuing right through to the birth. Braxton Hicks contractions tend to be irregular and while they are not generally painful, they can be uncomfortable and get progressively stronger through the pregnancy.

During true labour, the muscles of the uterus contract to help your baby move down into the birth canal. Labour contractions start like a wave and build in intensity, moving from the top of the uterus right down to the cervix. Your uterus will feel tight during the contraction, but between contractions, the pain will ease off and allow you to rest before the next one builds. Unlike Braxton Hicks, labour contractions become stronger, more regular and more frequent in the lead up to the birth.

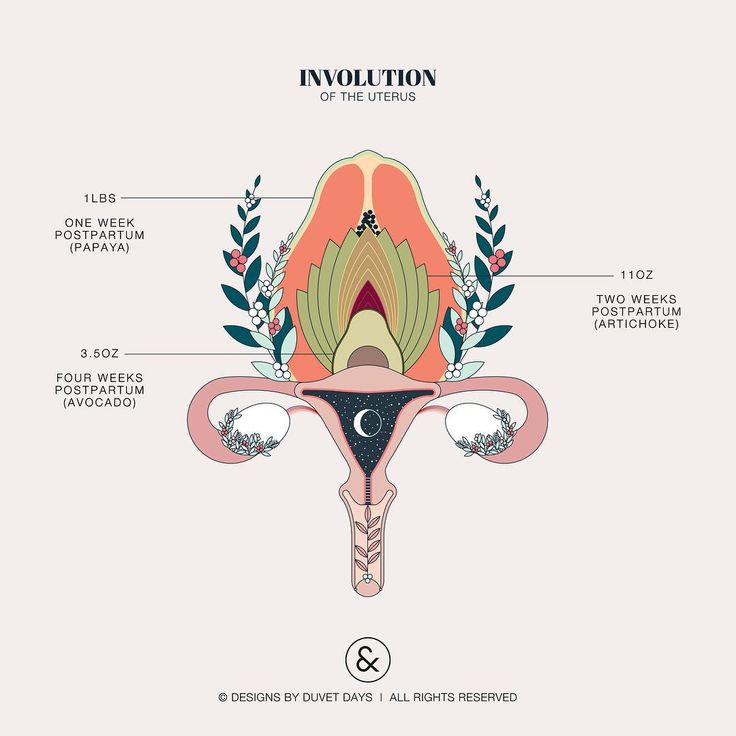

How does the uterus change after birth?

After the baby is born, the uterus will contract again to allow the placenta, which feeds the baby during pregnancy, to leave the woman’s body. This is sometimes called the ‘after birth’. These contractions are milder than the contractions felt during labour. Once the placenta is delivered, the uterus remains contracted to help prevent heavy bleeding known as ‘postpartum haemorrhage‘.

The uterus will also continue to have contractions after the birth is completed, particularly during breastfeeding. This contracting and tightening of the uterus will feel a little like period cramps and is also known as 'afterbirth pains'.

Read more here about the first few days after giving birth.

Sources:

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Labour and birth), StatPearls Publishing (Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis), Department of Health (Clinical practice guidelines: Pregnancy care), Better Health Channel Victoria (Pregnancy stages and changes), Mater Mother's Hospital (Labour and birth information), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (The First Few Weeks Following Birth), Queensland Health (Queensland Clinical Guidelines – maternity and neonatal), King Edward Memorial Hospital (Fundal height: Measuring with a tape measure), Royal Hospital for Women (Fetal growth assessment (clinical) in pregnancy), MSD Manual (Female internal genital organs)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: October 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - perineum and pelvic floor

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - cervix

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - abdominal muscles

- Anatomy of pregnancy and birth

Need more information?

Prolapsed uterus - Better Health Channel

The pelvic floor and associated supporting ligaments can be weakened or damaged in many ways, causing uterine prolapse.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Uterus, cervix & ovaries - fact sheet | Jean Hailes

This fact sheet discusses some of the health conditions that may affect a woman's uterus, cervix and ovaries.

Read more on Jean Hailes for Women's Health website

Dilatation and curettage (D&C)

A D&C is an operation to lightly scrape the inside of the uterus (womb).

Read more on WA Health website

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilised egg implants outside the uterus (womb)

Read more on WA Health website

Placental abruption - Better Health Channel

Placental abruption means the placenta has detached from the wall of the uterus, starving the baby of oxygen and nutrients.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Placenta complications in pregnancy

The placenta develops inside the uterus during pregnancy and provides your baby with nutrients and oxygen. If something goes wrong, it can be serious.

If something goes wrong, it can be serious.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Pelvic Floor | Family Planning NSW

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles in the pelvic area that support the bladder, bowel and uterus (womb).

Read more on Family Planning NSW website

Mirena IUD | Hormonal IUD Mirena | IUD Mirena insertion | IUD Mirena cost | Mirena IUD Melbourne - Sexual Health Victoria

The hormonal intrauterine device (IUD) is a small contraceptive device that is put into the uterus (womb) to prevent pregnancy.

Read more on Sexual Health Victoria website

Endometriosis | Your Fertility

Endometriosis is a condition where the tissue that lines the uterus also grows in other areas of the body

Read more on Your Fertility website

Pelvic Floor Muscle Damage - Birth Trauma

The pelvic floor muscles are a supportive basin of muscle attached to the pelvic bones by connective tissue to support the vagina, uterus, bladder and bowel.

Read more on Australasian Birth Trauma Association website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Physiology, Uterus - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

Adi Gasner; Aatsha P A.

Author Information

Last Update: May 19, 2022.

Introduction

The uterus is a female reproductive organ that is responsible for many functions in the processes of implantation, gestation, menstruation, and labor.

Anatomic Overview

The uterus is a thick-walled muscular structure that lies in the midline of the abdominal pelvic cavity. It contains three layers: the endometrium (innermost layer), myometrium, and the perimetrium (outermost layer). The endometrium’s thickness and structure vary based on hormonal stimulation

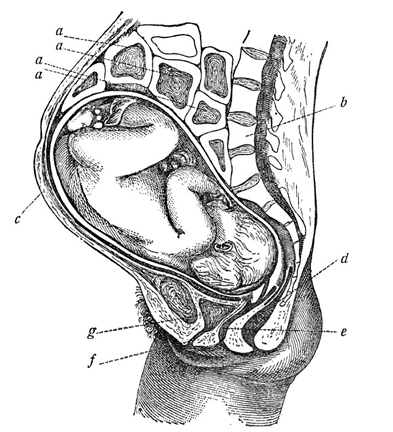

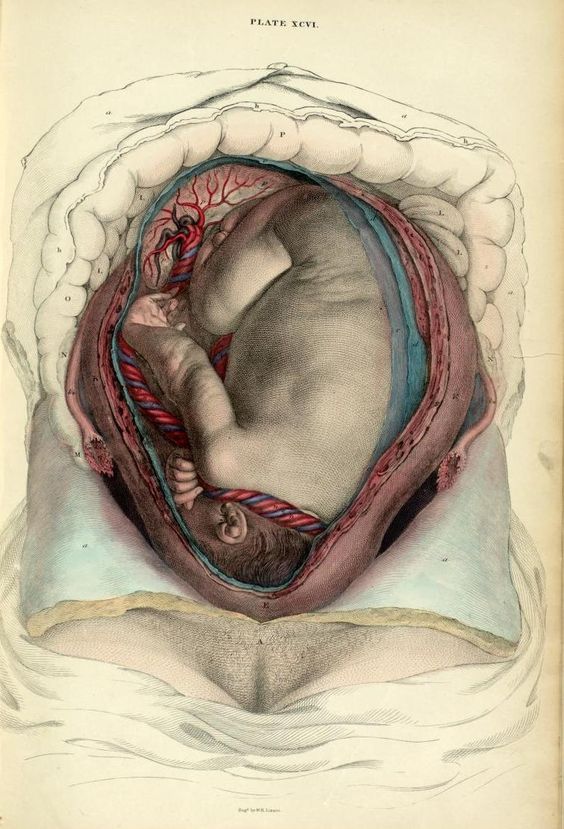

The uterus has four parts: the fundus, corpus, isthmus, and cervix. The corpus is the largest segment and connects to the cervix via the isthmus. The cervix connects the uterine body to the vaginal lumen. The uterus sits posterior to the bladder and anterior to the rectum.[1][2]

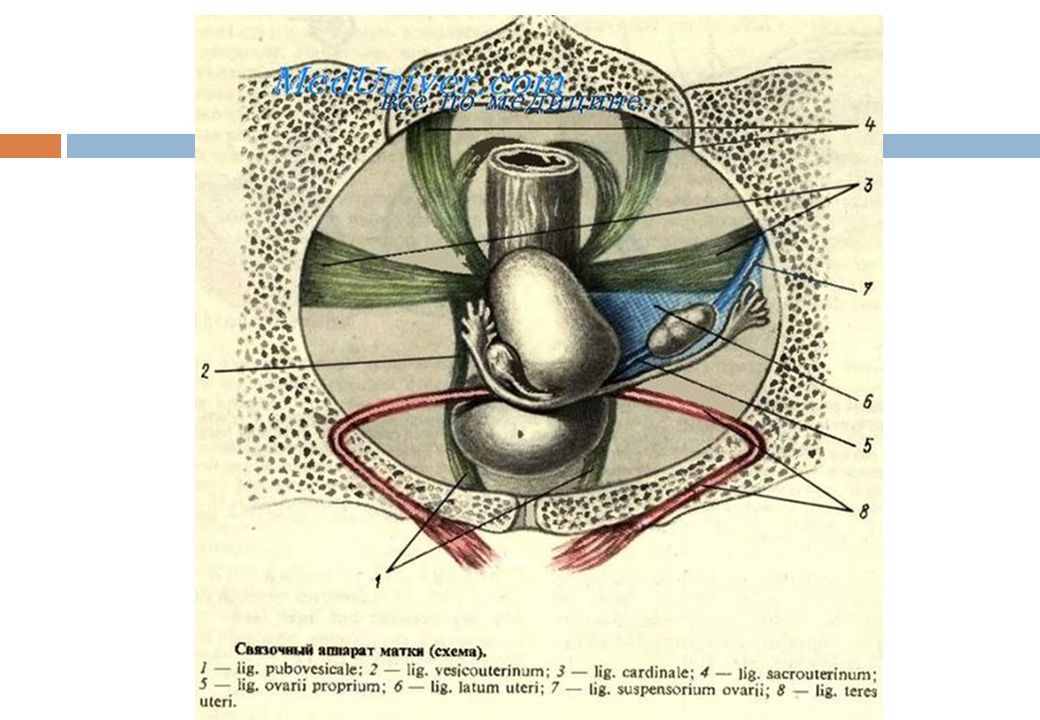

Uterus Support Structure

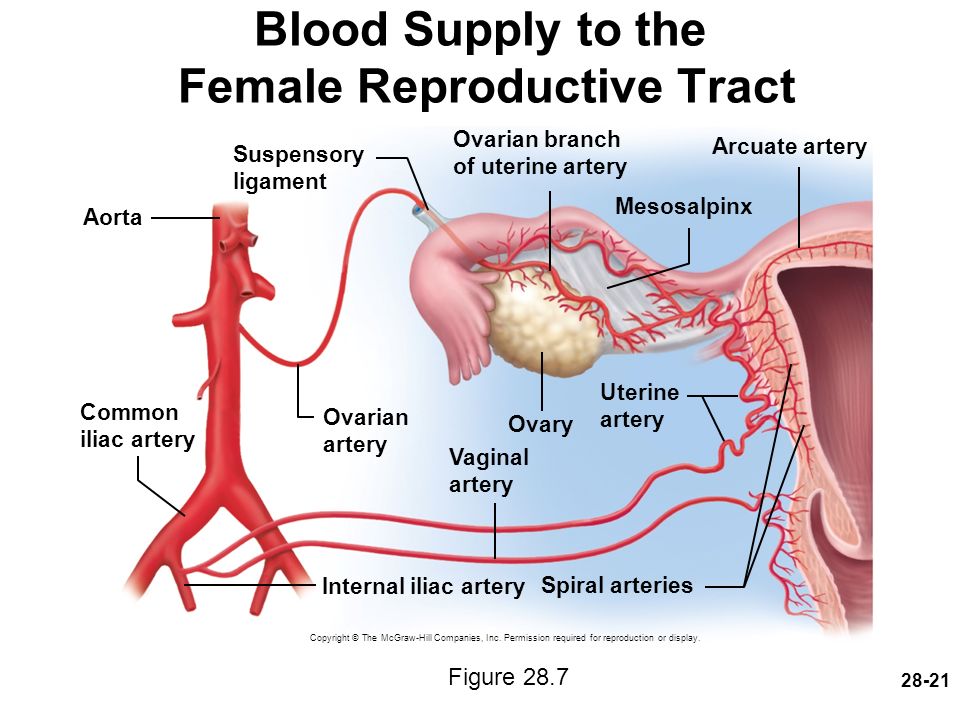

The round ligament connects the uterus to the abdominal wall and includes the artery of Sampson. The broad ligament connects the lateral portion of the uterus with the fallopian tube and ovary. The uterine artery, cardinal arteries, and ureter travel within the broad ligament. The ovarian ligament connects the ovary to the lateral surface of the uterus. The infundibulopelvic (IP) ligament connects the ovary to the abdominal wall. Within the IP ligament are the ovarian artery and vein.

The infundibulopelvic (IP) ligament connects the ovary to the abdominal wall. Within the IP ligament are the ovarian artery and vein.

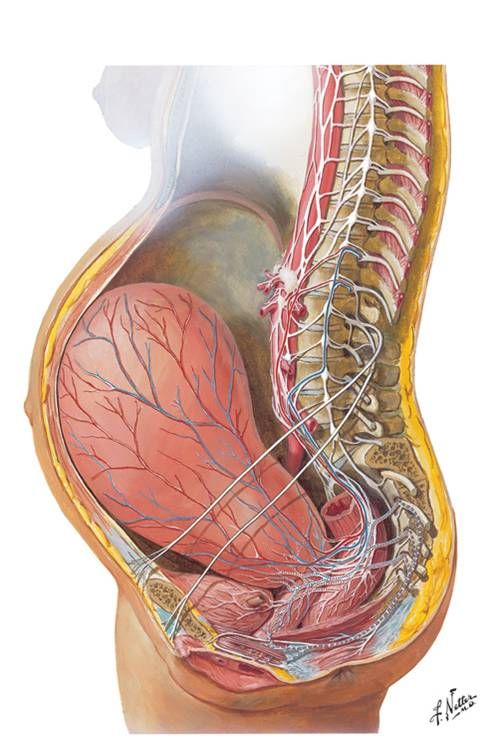

Uterine Vasculature

The uterine artery is the main blood supply to the uterus, with some collateral supply from the ovarian artery.

Uterine Innervation

The uterus is innervated sympathetically and parasympathetically through the hypogastric nerve and pelvic splanchnic nerves, respectively.[3][4][5]

Development

At 5 to 6 weeks gestation, the paramesonephric (Mullerian) ducts arise as coelomic epithelial invaginations that appear on the lateral surface of the paired urogenital ridges, the development of these ducts is due to the absence of anti-Mullerian hormone.[6][7] At eight weeks gestation, the paramesonephric ducts fuse vertically. The fused cranial and horizontal ends will give rise to what will ultimately become the fallopian tubes, while the caudal component will fuse to form the uterus, cervix, and upper third of the vagina. The uterine corpus remains underdeveloped at birth and reaches functional and anatomical maturity at the time of menarche.[8][9][10]

The uterine corpus remains underdeveloped at birth and reaches functional and anatomical maturity at the time of menarche.[8][9][10]

Function

The uterus carries out many functions:

Implantation site of the blastocyst

Provides protection and support for the fetus to grow

Site of menstruation

Mechanism

Reproductive Cycle

In the female reproductive cycle, there are two concurrent cycles, the ovarian cycle, and the uterine (menstrual) cycle. The ovarian cycle consists of a series of events that occur during and following oocyte maturation. The uterine cycle consists of a series of changes within the endometrium in preparation for the arrival of a fertilized ovum that will develop within the endometrium until birth.

The reproductive cycle can subdivide into the menstrual phase, preovulatory phase, ovulation, and postovulatory phase. The function of the uterus in each of these phases follows:

In the menstrual phase, a decline in estrogen and progesterone levels stimulates the release of prostaglandins, which results in vasoconstriction of arterioles within the uterus. The vasoconstriction eventually leads to hypoperfusion of these cells, which results in cell death. This process initiates the sloughing off of blood, fluid, and epithelial cells from the endometrial walls into the cervix and out through the vagina.

The vasoconstriction eventually leads to hypoperfusion of these cells, which results in cell death. This process initiates the sloughing off of blood, fluid, and epithelial cells from the endometrial walls into the cervix and out through the vagina.

In the preovulatory phase, estrogen is released into the blood, which repairs the endometrium. The endometrium undergoes other changes and doubles in thickness.

During ovulation, the follicle ruptures and releases an oocyte that enters the uterine tube.

In the postovulatory phase, progesterone and estrogen stimulate further growth of endometrial glands and thickening of the endometrium in preparation for the implantation of a fertilized ovum. If fertilization does not occur, progesterone end estrogen levels decline, and the menstruation stage occurs.

If the egg becomes fertilized, the zygote is propelled down the fallopian tubes into the uterus. The zygote cells divide rapidly during this descent. The cells of the zygote continue to divide until it becomes a blastocyst. This blastocyst implants by invading the wall of the endometrium.[11]

This blastocyst implants by invading the wall of the endometrium.[11]

Pregnancy

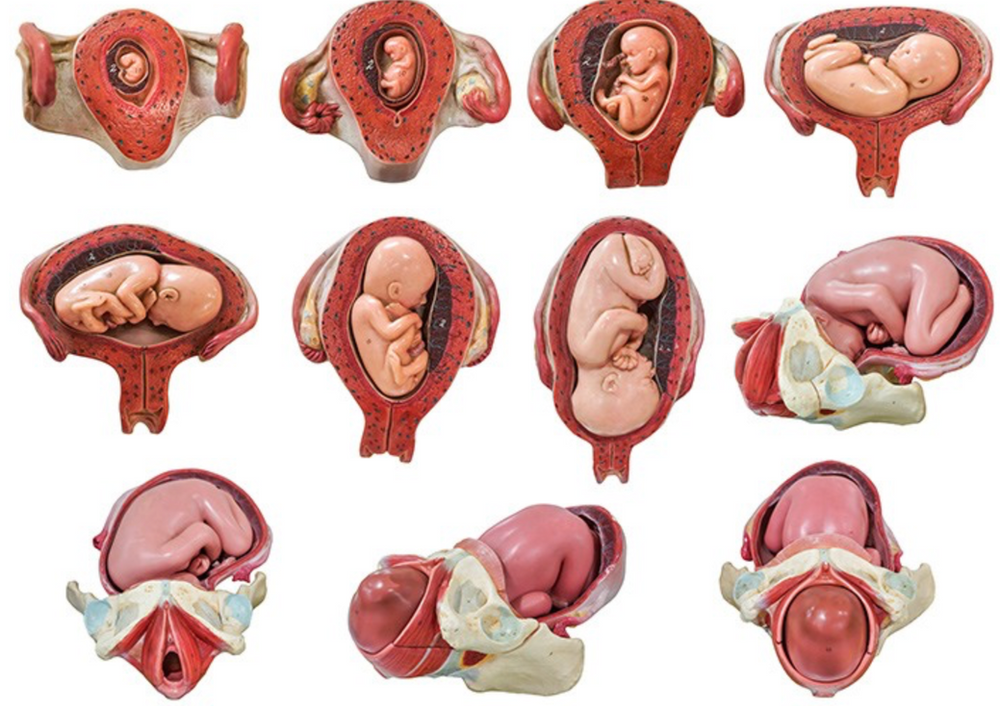

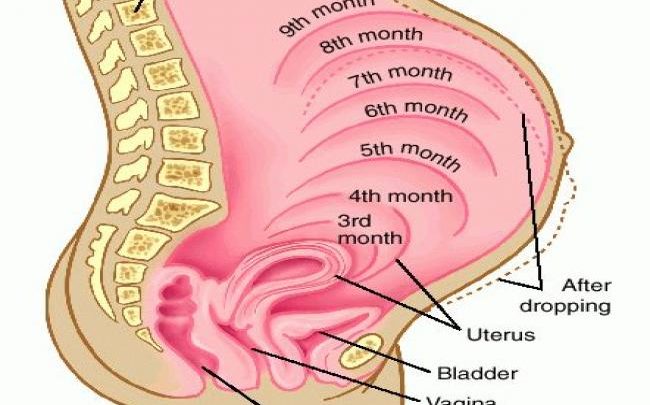

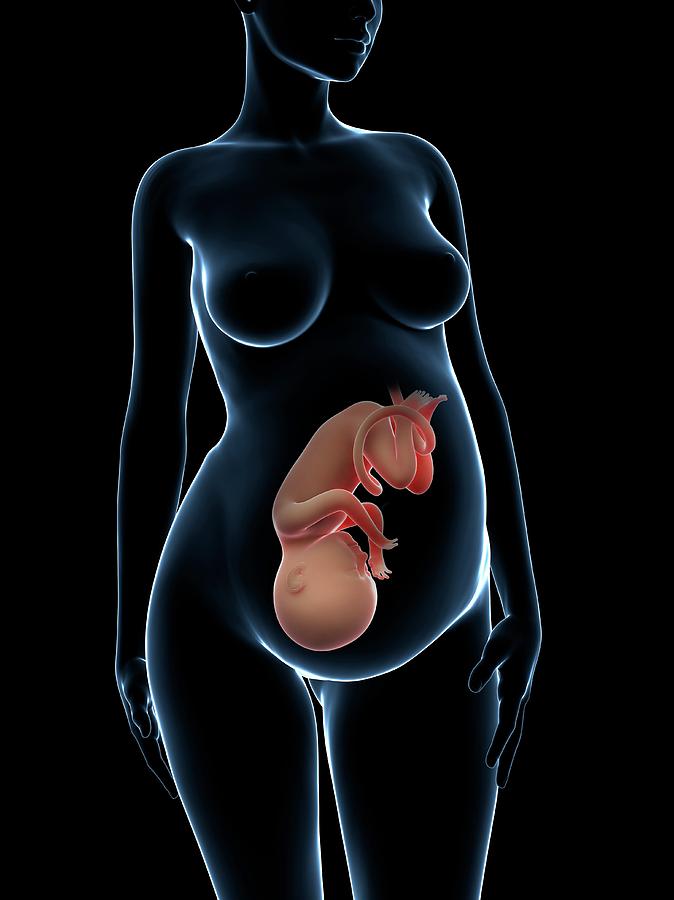

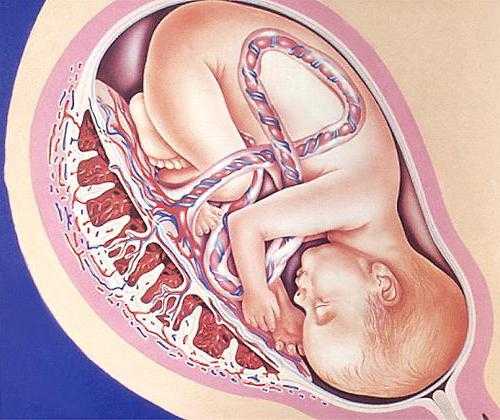

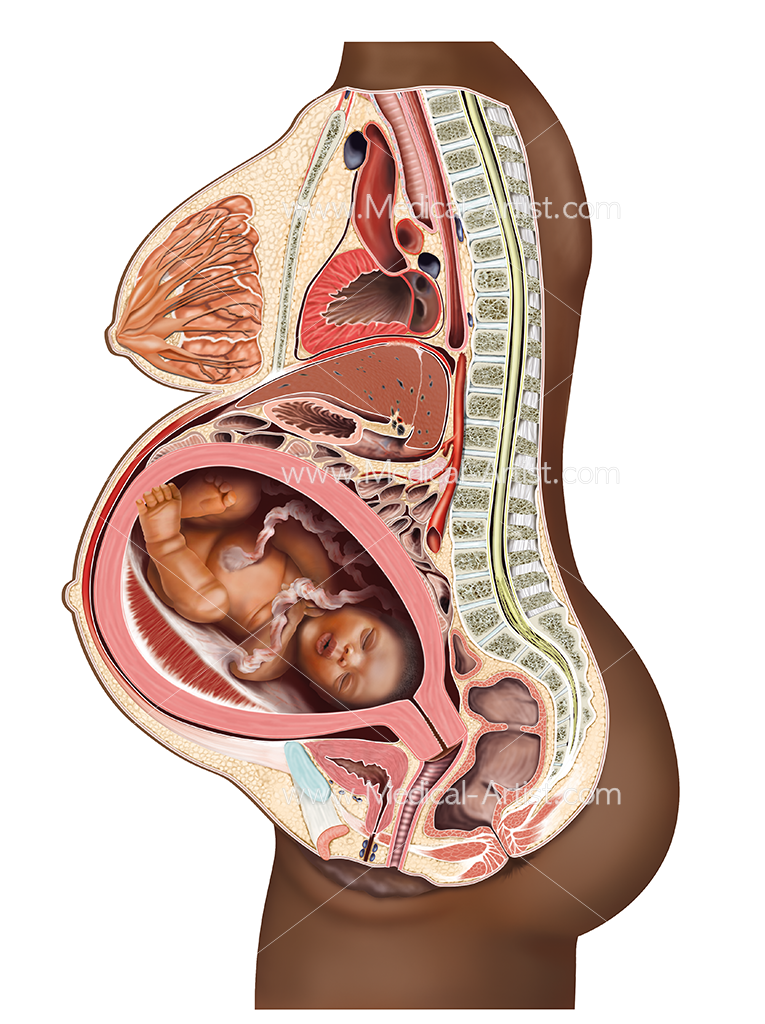

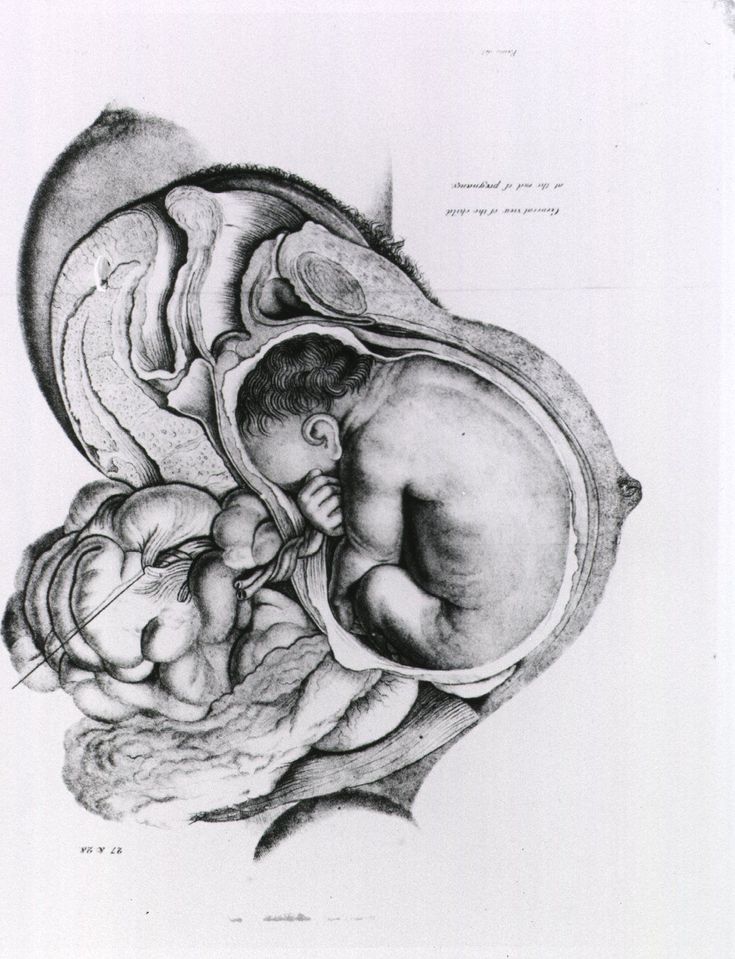

When the blastocyst successfully implants into the endometrial lining, it develops over many weeks into an embryo and then a fetus. During the development of an embryo into a fetus, changes occur within the endometrium that leads to placental formation. The placenta provides a crossing point between the developing fetus and maternal circulation. In pregnancy, the uterus hypertrophies to accommodate the growing fetus. It typically reaches the height of the umbilicus at 20 weeks and the xiphoid process at 38 weeks.

Labor

The uterus undergoes many changes during labor due to the release of various hormones. Nearing the seventh month of pregnancy, progesterone levels begin to decline while estrogen levels steadily rise. The increasing ratio of estrogen to progesterone causes the myometrium to become more sensitive to stimuli that promote contractions. Additionally, fetal cortisol rises in the eighth month of pregnancy, which further reduces progesterone’s effects. [12][13]

[12][13]

As true labor approaches, oxytocin and prostaglandins both play a role in further stimulating myometrial contractions and increasing contractile strength. The fetus causes the myometrium and cervix to stretch, which also stimulates uterine contractions.[14]

During true labor, the release of oxytocin and prostaglandins stimulate a positive feedback loop which continues to increase uterine contractile strength. These uterine contractions dilate and efface the cervix. Again a positive feedback loop begins where the effacement and dilation of the cervix further promote uterine contractions. Contractions become more frequent and longer in duration as labor progresses. The next stage of labor begins when the fetal head enters the birth canal and completes when the infant is born. The myometrium continues to contract after birth, causing the placenta to shear from the back of the uterine wall for delivery through the birth canal.[15]

Pathophysiology

Within uterine development, Mullerian duct abnormalities can be present. These can include incomplete fusion of the Mullerian ducts during embryogenesis, leading to abnormal uterine development. There are also a host of acquired uterine conditions that can occur in any of the three uterine layers but most commonly target the endometrium and myometrium. In acquired or congenital uterine abnormalities, patients can either appear symptomatic or have associated complications such as infertility, recurrent miscarriages, and prematurity. Appropriate application of the function and common pathologies of the uterus can directly impact the mortality and morbidity of women everywhere, especially as it relates to pregnancy-related changes. A discussion of the most common pathologies in each of these categories will appear below.

These can include incomplete fusion of the Mullerian ducts during embryogenesis, leading to abnormal uterine development. There are also a host of acquired uterine conditions that can occur in any of the three uterine layers but most commonly target the endometrium and myometrium. In acquired or congenital uterine abnormalities, patients can either appear symptomatic or have associated complications such as infertility, recurrent miscarriages, and prematurity. Appropriate application of the function and common pathologies of the uterus can directly impact the mortality and morbidity of women everywhere, especially as it relates to pregnancy-related changes. A discussion of the most common pathologies in each of these categories will appear below.

Clinical Significance

Congenital Defects

The septate uterus is the most common structural uterine anomaly.[16] It occurs when the partition between the two fused Mullerian ducts fails to resorb. This remnant results in a fibromuscular septum that can be partial or complete, which would divide the uterine cavity and cervix into two separate components. [17] Uterus didelphys occurs when there is a complete failure of fusion of the paired Mullerian ducts. As such, the uterus presents as a paired organ with two endometrial cavities, each with a cervix.[18] Additionally, a bicornuate uterus is a structural anomaly that can occur. In this condition, there is an incomplete fusion of the paramesonephric ducts, which produces a bicornuate uterus. Similar to uterus didelphys, there are two separate endometrial cavities; however, there is one cervix.[18]

[17] Uterus didelphys occurs when there is a complete failure of fusion of the paired Mullerian ducts. As such, the uterus presents as a paired organ with two endometrial cavities, each with a cervix.[18] Additionally, a bicornuate uterus is a structural anomaly that can occur. In this condition, there is an incomplete fusion of the paramesonephric ducts, which produces a bicornuate uterus. Similar to uterus didelphys, there are two separate endometrial cavities; however, there is one cervix.[18]

Acquired Conditions

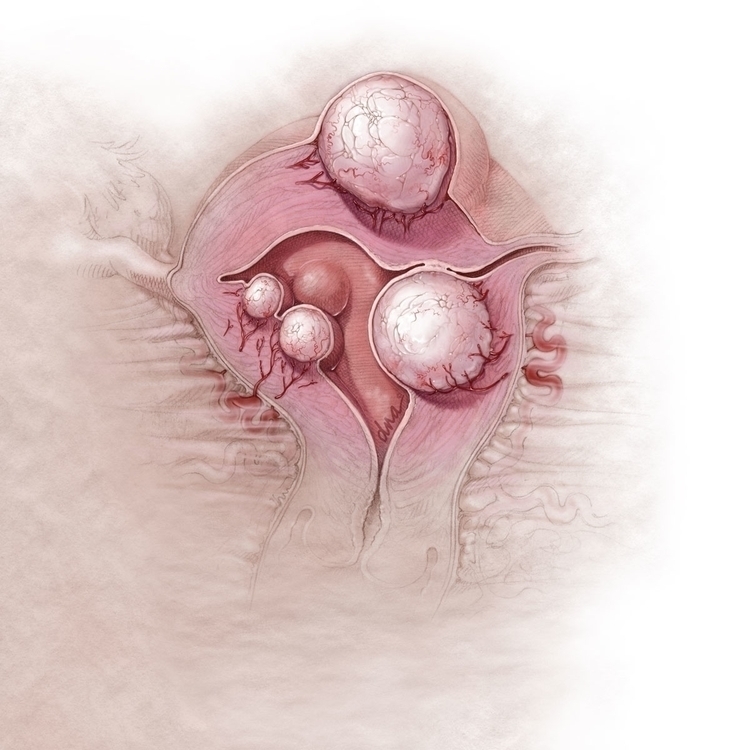

One of the most common diseases of the uterus is uterine fibroids, also known as leiomyomata. This disorder characteristically presents with benign, smooth muscle tumors found in the myometrial layer [18]. Another condition that affects the myometrium is adenomyosis. In this disease, endometrial tissue embeds into the myometrium, which can result in abnormal uterine bleeding and secondary dysmenorrhea.[19]

A common pathology affecting the endometrium is endometriosis. This condition is an estrogen-dependent disorder characterized by glandular tissue and stroma outside the uterine cavity.[20] It can often be accompanied by dyspareunia, bleeding, dysmenorrhea, and infertility.[21] Endometrial polyps are another common pathology that causes benign, local overgrowths of endometrial tissue.[21] Endometritis, an inflammatory disorder of the endometrium, is due to a bacterial infection either from external bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis or from the normal bacterial flora found in the vagina.[22] Another condition that can affect the endometrium is endometrial hyperplasia, which is caused by excessive growth of endometrial glands due to increased unopposed exposure to estrogen and can be a predisposing factor for endometrial carcinoma.[23]

This condition is an estrogen-dependent disorder characterized by glandular tissue and stroma outside the uterine cavity.[20] It can often be accompanied by dyspareunia, bleeding, dysmenorrhea, and infertility.[21] Endometrial polyps are another common pathology that causes benign, local overgrowths of endometrial tissue.[21] Endometritis, an inflammatory disorder of the endometrium, is due to a bacterial infection either from external bacteria such as Chlamydia trachomatis or from the normal bacterial flora found in the vagina.[22] Another condition that can affect the endometrium is endometrial hyperplasia, which is caused by excessive growth of endometrial glands due to increased unopposed exposure to estrogen and can be a predisposing factor for endometrial carcinoma.[23]

Endometrial carcinoma is a common gynecological malignancy and the most common type of uterine cancer. Its characteristics include malignant cells arising in the endometrial layer. It classifies into two major types: Type I and Type II and can present with abnormal uterine bleeding, including post-menopausal bleeding. [24][25]

[24][25]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Roach MK, Andreotti RF. The Normal Female Pelvis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;60(1):3-10. [PubMed: 28005593]

- 2.

Cooke PS, Spencer TE, Bartol FF, Hayashi K. Uterine glands: development, function and experimental model systems. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013 Sep;19(9):547-58. [PMC free article: PMC3749806] [PubMed: 23619340]

- 3.

Kido A, Togashi K. Uterine anatomy and function on cine magnetic resonance imaging. Reprod Med Biol. 2016 Oct;15(4):191-199. [PMC free article: PMC5715863] [PubMed: 29259437]

- 4.

Ameer MA, Fagan SE, Sosa-Stanley JN, Peterson DC. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Feb 23, 2022. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Uterus. [PubMed: 29262069]

- 5.

Rosner J, Samardzic T, Sarao MS.

StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Oct 9, 2021. Physiology, Female Reproduction. [PubMed: 30725817]

StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Oct 9, 2021. Physiology, Female Reproduction. [PubMed: 30725817]- 6.

Moncada-Madrazo M, Rodríguez Valero C. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 31, 2021. Embryology, Uterus. [PubMed: 31613528]

- 7.

Cunha GR, Kurita T, Cao M, Shen J, Cooke PS, Robboy SJ, Baskin LS. Tissue interactions and estrogenic response during human female fetal reproductive tract development. Differentiation. 2018 May - Jun;101:39-45. [PMC free article: PMC5993605] [PubMed: 29684808]

- 8.

Sulak O, Cosar F, Malas MA, Cankara N, Cetin E, Tagil SM. Anatomical development of the fetal uterus. Early Hum Dev. 2007 Jun;83(6):395-401. [PubMed: 17045762]

- 9.

Ye L, Mayberry R, Lo CY, Britt KL, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Gargett CE. Generation of human female reproductive tract epithelium from human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21136.

[PMC free article: PMC3115988] [PubMed: 21698266]

[PMC free article: PMC3115988] [PubMed: 21698266]- 10.

Cunha GR, Robboy SJ, Kurita T, Isaacson D, Shen J, Cao M, Baskin LS. Development of the human female reproductive tract. Differentiation. 2018 Sep - Oct;103:46-65. [PMC free article: PMC6234064] [PubMed: 30236463]

- 11.

Kapila V, Chaudhry K. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 26, 2021. Physiology, Placenta. [PubMed: 30855916]

- 12.

Chwalisz K, Garfield RE. Regulation of the uterus and cervix during pregnancy and labor. Role of progesterone and nitric oxide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997 Sep 26;828:238-53. [PubMed: 9329845]

- 13.

Olson DM, Mijovic JE, Sadowsky DW. Control of human parturition. Semin Perinatol. 1995 Feb;19(1):52-63. [PubMed: 7754411]

- 14.

Hutchison J, Mahdy H, Hutchison J. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Feb 26, 2022. Stages of Labor. [PubMed: 31335010]

- 15.

Gross MM. [The five stages of labour]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2002 Nov-Dec;206(6):236-41. [PubMed: 12476398]

- 16.

Raga F, Bauset C, Remohi J, Bonilla-Musoles F, Simón C, Pellicer A. Reproductive impact of congenital Müllerian anomalies. Hum Reprod. 1997 Oct;12(10):2277-81. [PubMed: 9402295]

- 17.

Taylor E, Gomel V. The uterus and fertility. Fertil Steril. 2008 Jan;89(1):1-16. [PubMed: 18155200]

- 18.

Patton PE. Anatomic uterine defects. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Sep;37(3):705-21. [PubMed: 7955655]

- 19.

Pavlik RM. Adenomyosis--an ignored uterine disease. Nurse Pract. 1995 Apr;20(4):32-4, 39-40, 43. [PubMed: 7596529]

- 20.

Lim HJ, Wang H. Uterine disorders and pregnancy complications: insights from mouse models. J Clin Invest. 2010 Apr;120(4):1004-15. [PMC free article: PMC2846054] [PubMed: 20364098]

- 21.

Cakmak H, Taylor HS. Implantation failure: molecular mechanisms and clinical treatment.

Hum Reprod Update. 2011 Mar-Apr;17(2):242-53. [PMC free article: PMC3039220] [PubMed: 20729534]

Hum Reprod Update. 2011 Mar-Apr;17(2):242-53. [PMC free article: PMC3039220] [PubMed: 20729534]- 22.

Kitaya K, Takeuchi T, Mizuta S, Matsubayashi H, Ishikawa T. Endometritis: new time, new concepts. Fertil Steril. 2018 Aug;110(3):344-350. [PubMed: 29960704]

- 23.

Reed SD, Newton KM, Clinton WL, Epplein M, Garcia R, Allison K, Voigt LF, Weiss NS. Incidence of endometrial hyperplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jun;200(6):678.e1-6. [PMC free article: PMC2692753] [PubMed: 19393600]

- 24.

Sorosky JI. Endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Aug;120(2 Pt 1):383-97. [PubMed: 22825101]

- 25.

Di Cristofano A, Ellenson LH. Endometrial carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:57-85. [PubMed: 18039093]

Uterus / Female Anatomy - Alexander Nikitin. Tel: +7(926)278-67-02

The uterus is a muscular organ that resembles a bag. The uterus is a fruit-bearing place. Her task is to bear the fetus and push it out at the right time. The uterus is anatomically divided into the body and the cervix. The cervix has a cylindrical shape, half located in the vaginal cavity. During pregnancy, the cervix is closed and holds the fetus in the uterus. During childbirth, the cervix gradually opens and releases the fetus from the uterus.

The uterus is anatomically divided into the body and the cervix. The cervix has a cylindrical shape, half located in the vaginal cavity. During pregnancy, the cervix is closed and holds the fetus in the uterus. During childbirth, the cervix gradually opens and releases the fetus from the uterus.

The body of the uterus has three layers:

- endometrium

- myometrium

- serous

Endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus. The endometrium is an epithelium (layer of cells) whose task is to receive a fertilized egg. For a better understanding, I compare the endometrium with fertile soil in which a seed (fertilized egg) has fallen. Like a sprout in the ground, pregnancy begins its development in the endometrium.

The endometrium consists of two layers: basal and functional.

The basal layer is the inner layer. From the cells of the basal layer after menstruation, a functional layer is formed.

The functional layer is formed in the intervals between menstruation and is rejected during it. In the functional layer of the endometrium, pregnancy begins to develop.

To give an understanding of the function of the endometrium, you need to talk about the woman's menstrual cycle. The menstrual cycle begins with menstruation, but menstruation is the rejection of the endometrium, so it is more logical to start talking about the endometrium from the stage of its new growth, that is, immediately after menstruation.

Normally, menstruation lasts 3-5 days. Then the cells of the basal layer of the endometrium give rise to new cells - the cells of the functional layer. Under the influence of estrogens (ovarian hormones), the functional layer becomes lush, glands form in it. The endometrium prepares for the acceptance (implantation) of a fertilized egg. By the middle of the cycle (day 14, ovulation time), the functional layer of the endometrium is formed.

In the second phase of the menstrual cycle (after ovulation), the endometrial glands begin to function, that is, to secrete substances that contribute to the development of pregnancy in it. This happens under the influence of the hormone of the second phase of the menstrual cycle - progesterone. It is also called the pregnancy hormone. For a better understanding, here I will give a comparison. The endometrium in the first phase of the menstrual cycle can be compared to plowed and loosened soil. In the second phase - with soil that is well fertilized. Endometrial glands under the influence of progesterone saturate the endometrium, make it loose, juicy, nutritious. Such an endometrium creates good conditions for the development of pregnancy.

This happens under the influence of the hormone of the second phase of the menstrual cycle - progesterone. It is also called the pregnancy hormone. For a better understanding, here I will give a comparison. The endometrium in the first phase of the menstrual cycle can be compared to plowed and loosened soil. In the second phase - with soil that is well fertilized. Endometrial glands under the influence of progesterone saturate the endometrium, make it loose, juicy, nutritious. Such an endometrium creates good conditions for the development of pregnancy.

If pregnancy does not occur, then under hormonal influence, the functional layer of the endometrium is rejected. The bulk of the endometrium falls out through the vagina, a small part - through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity. The process of rejection of the endometrium, accompanied by bleeding, is called menstruation.

Summary. The menstrual cycle is a cyclical change in a woman's body. The menstrual cycle normally lasts 28 days. It is best represented in the endometrium and ovaries. The menstrual cycle consists of two parts (phases). The border between them is ovulation. The menstrual cycle begins with menstruation, then the functional layer of the endometrium grows. In the middle of the cycle, ovulation occurs, then the endometrium becomes lush under the influence of progesterone. If pregnancy does not occur, then the endometrium is rejected - a new menstrual cycle begins.

It is best represented in the endometrium and ovaries. The menstrual cycle consists of two parts (phases). The border between them is ovulation. The menstrual cycle begins with menstruation, then the functional layer of the endometrium grows. In the middle of the cycle, ovulation occurs, then the endometrium becomes lush under the influence of progesterone. If pregnancy does not occur, then the endometrium is rejected - a new menstrual cycle begins.

Myometrium is the middle layer of the uterus (muscular layer). The task of this shell is to serve as a reliable wall of the fetus, and during childbirth to push the fetus through the birth canal.

Serous layer. Outside, the body of the uterus is covered with a membrane that covers other organs of the abdominal cavity. It is called the serosa or peritoneum.

Physiological pregnancy

Gynecology

Pregnancy is a physiological process of development of a fertilized ovum in the female body, starting from the moment of fertilization of the ovum matured in the ovary by a spermatozoon. Fertilization usually occurs in the ampulla, facing the ovary, the fallopian tube.

Fertilization usually occurs in the ampulla, facing the ovary, the fallopian tube.

What you need to know about pregnancy

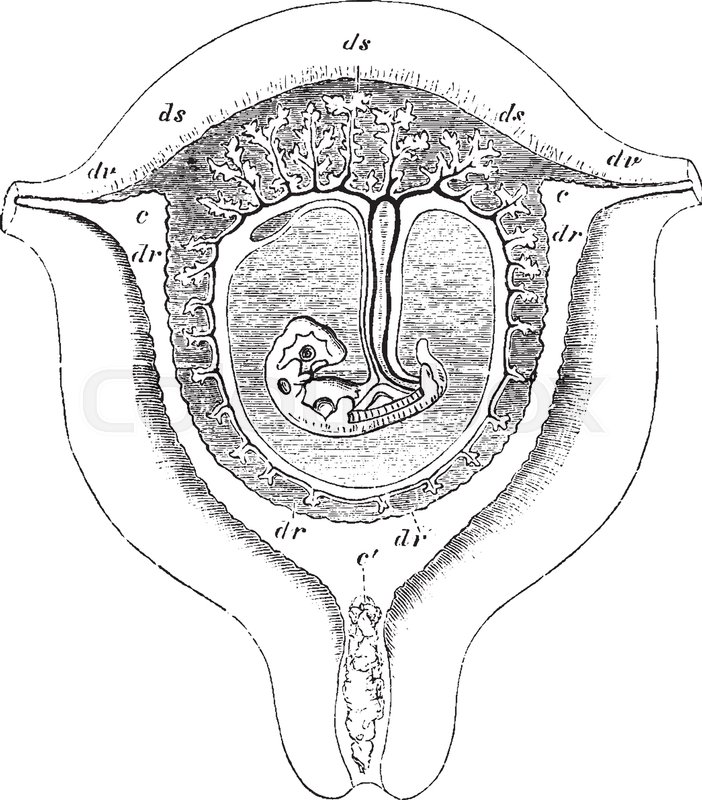

Thanks to the rhythmic contractions of the tube, the fertilized egg moves into the uterine cavity. During this promotion, the egg gradually turns into a multicellular embryo - a fetal egg, densely covered with delicate villi - with their help it attaches to the mucous membrane lining the inner surface of the uterus. From the moment of attachment, the formation of the embryo, and then the fetus, begins, accompanied by a restructuring of all the functions and systems of the woman's body, which in essence are adaptive reactions that provide favorable conditions for the development of the fetus.

At the site of attachment of the embryo, the villi grow luxuriantly, and from them the so-called baby place or placenta is formed, connected to the fetus by the umbilical cord. Nutrients and oxygen flow through the placenta from the mother to the fetus through the blood vessels of the umbilical cord, and metabolic products are removed.

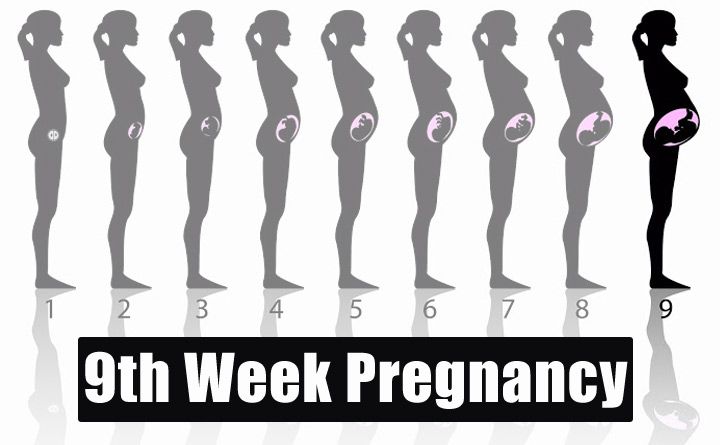

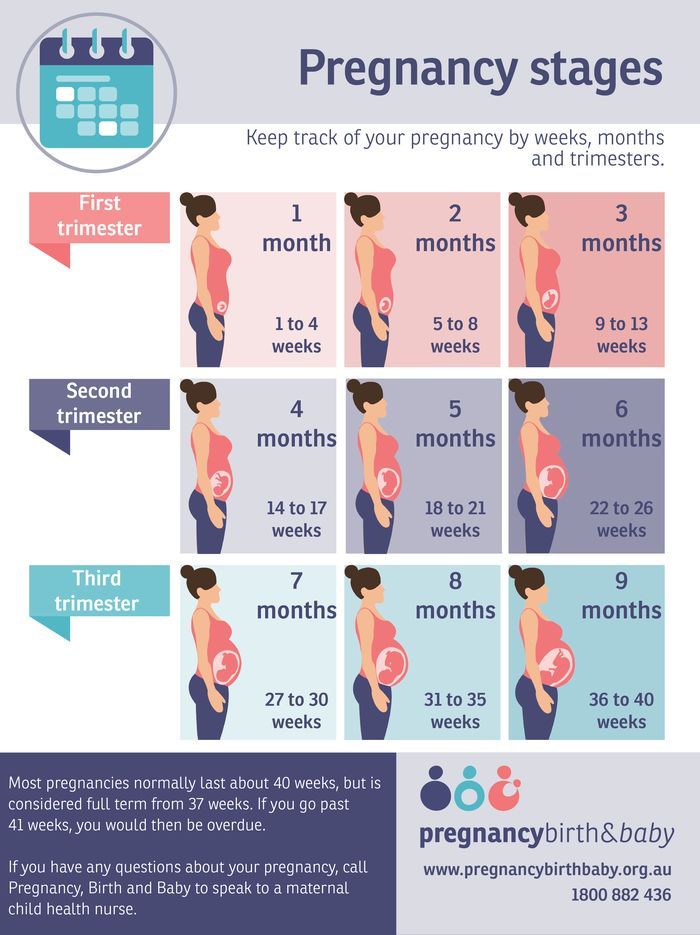

Physiological pregnancy lasts an average of 10 lunar months (1 lunar month - 28 days), i.e. 40 weeks or 280 days. The course of pregnancy is usually divided into trimesters: the first begins with fertilization and ends at 12-13 weeks, the second ends at 28 weeks, from the same period the third trimester of pregnancy begins, ending with childbirth.

The possibility of pregnancy can and should be considered in any woman of childbearing age who misses her period or develops amenorrhea (absence of menstruation) during regular intercourse. Thus, the first sign of pregnancy is usually the absence of menstruation at the proper time.

A few days after the period of missed menstruation, most women experience nausea and even vomiting. Vomiting usually happens once or twice a day, in the morning, immediately after getting out of bed, but it is not so strong as to cause a noticeable metabolic disorder. Often there is an increase in urination, which, however, can occur in non-pregnant women in the premenstrual period, but in pregnant women it is more noticeable.

Changes in the mammary glands are also noted from the very beginning of pregnancy and are especially noticeable in women who are pregnant for the first time. And from about the 12th week, it is already possible to feel the bottom of the uterus through the anterior abdominal wall, which on the 20th week approaches the lower edge of the navel, and on the 36th - to the xiphoid process of the sternum.

Multi-pregnant women notice fetal movements earlier than those who become pregnant for the first time. The former usually notice movements between 16 and 18 weeks, and the latter between 19 and 21. Data on these sensations can be very important in determining the duration of pregnancy and the upcoming birth, so a woman should try to remember the date of the first movement of the fetus.

Of course, there are more accurate special methods for diagnosing pregnancy. Initially, especially in doubtful cases, a woman can determine the onset of pregnancy on her own using an express pregnancy test (a test strip that she can purchase at a pharmacy).

In our Clinic, we can also conduct an urgent study of the level of human chorionic gonadotropin , often called the “hormone of pregnancy”. And modern diagnostic ultrasound scanners, such as, for example, the Sonix OP used in the LeVita Clinic, allow you to establish pregnancy at a minimum period of 2-3 weeks. The accuracy of diagnosis increases during transvaginal scanning - when a special sensor is inserted into the lumen of the vagina and the study is carried out as if from the inside (of course, all sanitary and epidemic requirements are observed).

A pregnant woman must be registered at the antenatal clinic and the sooner the better: at the beginning of pregnancy, she still remembers the days of her last menstruation exactly, which is important for determining the gestational age, and the accuracy of her information can be clarified by simple methods, for example, at a gynecological inspection.

In addition, it is during this period that the doctor needs to obtain her initial data: about the patient's usual pulse rate, blood pressure, blood hemoglobin level, body weight - in order to quickly assess the current situation in case of their changes at later stages of pregnancy and, if necessary, to make the necessary decision without delay. At the same time, the doctor also needs to identify concomitant diseases of the pregnant woman, such as hypertension or heart disease, peptic ulcer or diabetes mellitus, which can have a significant impact on the course of pregnancy, the condition of the expectant mother and her child, and accordingly draw up tactics for managing pregnancy.

At the same time, the doctor also needs to identify concomitant diseases of the pregnant woman, such as hypertension or heart disease, peptic ulcer or diabetes mellitus, which can have a significant impact on the course of pregnancy, the condition of the expectant mother and her child, and accordingly draw up tactics for managing pregnancy.

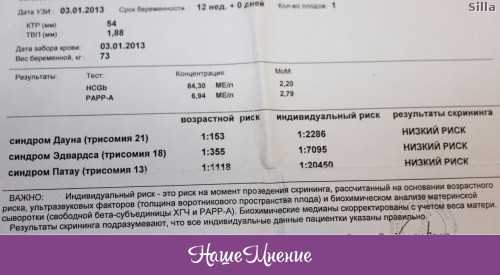

The primary medical examination also includes the determination of such important parameters as blood group and Rh factor, serological tests for syphilis, HIV infection, hepatitis B and C, as well as indicators of a biochemical blood test, coagulogram data (coagulability analysis ) etc. In addition, women with a certain frequency undergo an ultrasound examination, which is permissible at any time: its harmlessness has been confirmed by numerous studies that have been conducted for more than 50 years all over the world.

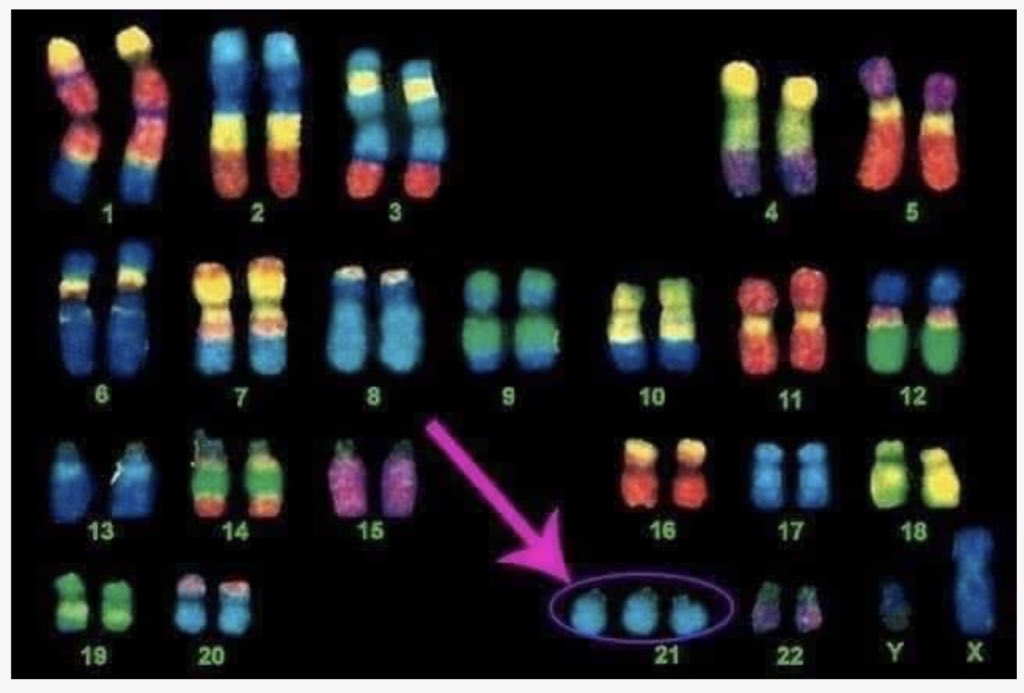

If a woman is over thirty-five years old, then there is a risk of her developing chromosomal abnormalities that can lead to the development of various fetal malformations (the most common is Down's disease). In these cases, the doctor usually recommends undergoing a special examination - amniocentesis, in which the wall of the uterus and the fetal bladder are punctured with a thin needle, and the resulting amniotic fluid is sent for analysis.

In these cases, the doctor usually recommends undergoing a special examination - amniocentesis, in which the wall of the uterus and the fetal bladder are punctured with a thin needle, and the resulting amniotic fluid is sent for analysis.

In general, pregnancy can be viewed as a process of prolonged physical adaptation of the mother's body to meet the needs of the growing fetus. The degree of this adaptation as a whole exceeds the needs of the fetus, therefore, a woman always has significant reserves that allow her to endure periods of stress or deprivation without significant changes in the environment of the fetus.

Each of the systems of a woman's body undergoes serious changes and trials. For example, mean arterial pressure, apart from a tendency to drop slightly in mid-pregnancy, rises slightly, facilitating the transfer of oxygen from the mother to the fetus. Speaking about changes in the vascular system, we note that pregnant women experience vasodilatation of the skin, as a result of which a woman feels less cold, but sometimes she may feel worse in hot weather. As the pregnancy progresses, the movement of the diaphragm is greatly restricted, and breathing by its nature becomes rapid and predominantly chesty.

As the pregnancy progresses, the movement of the diaphragm is greatly restricted, and breathing by its nature becomes rapid and predominantly chesty.

The increase in the body weight of a pregnant woman is characterized by significant individual fluctuations, but on average, during pregnancy, a woman gains weight up to 12 kg. A third of the increase, about 4 kg, is gained in the first half of pregnancy, and the remaining two-thirds in the second. More than half of the total body weight gain is due to fluid retention, which is distributed between the blood plasma, fetus, placenta, amniotic fluid and other tissues. After a sharp decrease in body weight in the first four days after delivery due to separation of the fetus, placenta, amniotic fluid and uterine contractions, as well as increased diuresis, weight continues to decrease gradually over the next 3 months or so.

Changes in the mammary glands are also characteristic - usually women feel some stretching and soreness. The swollen mouths of the glands of the areola around the nipple may protrude upward, forming the so-called Montgomery tubercles. With sufficient light, swelling of the superficial veins becomes visible, especially around the nipple. The breast loses its usual softness and in it one can feel the strands of swollen glandular ducts running from the periphery to the nipple like spokes in a wheel. After 14 weeks, discharge from the nipple appears, progressing as the pregnancy progresses, and the mammary glands noticeably increase in size. After 16 weeks, pigmentation of the nipple becomes noticeable, especially pronounced in swarthy women. In pregnant women, skin pigmentation also increases, especially pronounced on the face, around the nipples and the white line of the abdomen. This phenomenon is due to an increase in the amount of circulating melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Longitudinal stripes appear on the abdomen and thighs - "stretch marks" 5-8 cm long and about 0.5 cm wide. At first they are pink, but then they become paler and slightly condensed.

The swollen mouths of the glands of the areola around the nipple may protrude upward, forming the so-called Montgomery tubercles. With sufficient light, swelling of the superficial veins becomes visible, especially around the nipple. The breast loses its usual softness and in it one can feel the strands of swollen glandular ducts running from the periphery to the nipple like spokes in a wheel. After 14 weeks, discharge from the nipple appears, progressing as the pregnancy progresses, and the mammary glands noticeably increase in size. After 16 weeks, pigmentation of the nipple becomes noticeable, especially pronounced in swarthy women. In pregnant women, skin pigmentation also increases, especially pronounced on the face, around the nipples and the white line of the abdomen. This phenomenon is due to an increase in the amount of circulating melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Longitudinal stripes appear on the abdomen and thighs - "stretch marks" 5-8 cm long and about 0.5 cm wide. At first they are pink, but then they become paler and slightly condensed.