Red blood cell count in pregnancy

Physiological Changes in Hematological Parameters During Pregnancy

Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2012 Sep; 28(3): 144–146.

Published online 2012 Jul 15. doi: 10.1007/s12288-012-0175-6

,1,1,1,1 and 2

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Pregnancy is a state characterized by many physiological hematological changes, which may appear to be pathological in the non-pregnant state. The review highlights most of these changes along with the scientific basis for the same, as per the current knowledge, with a special reference to the red blood and white blood cells, platelets and hemostatic profile.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Physiological, Hematological changes

Physiological changes in pregnancy and puerperium are principally influenced by changes in the hormonal milieu. Many hematological changes also, occurring during these periods are physiological and are of inconsequential concern to the hematologist.

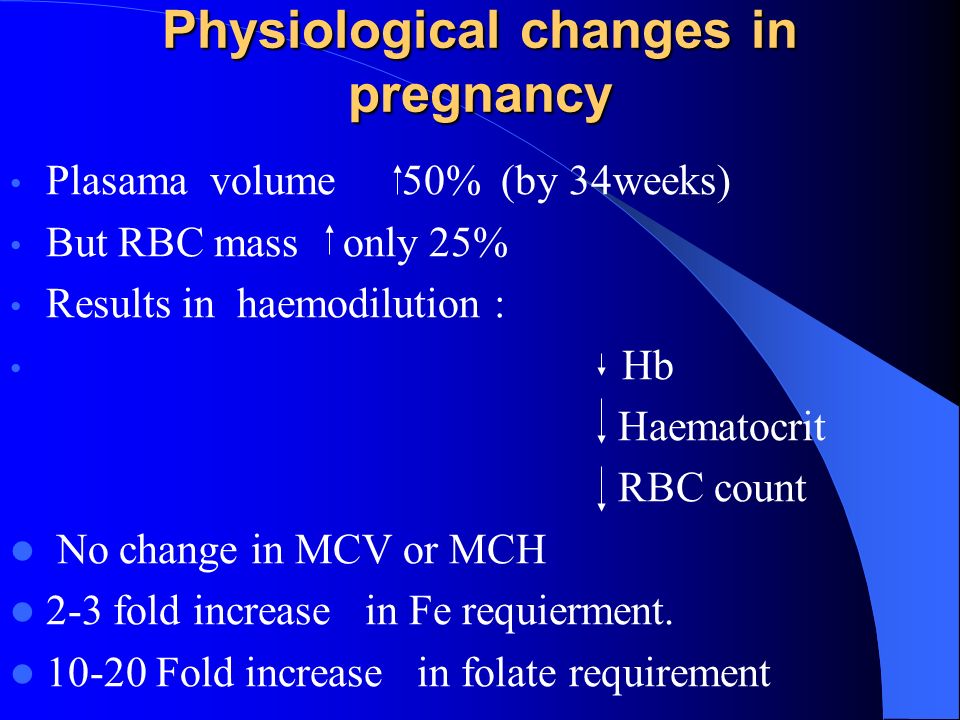

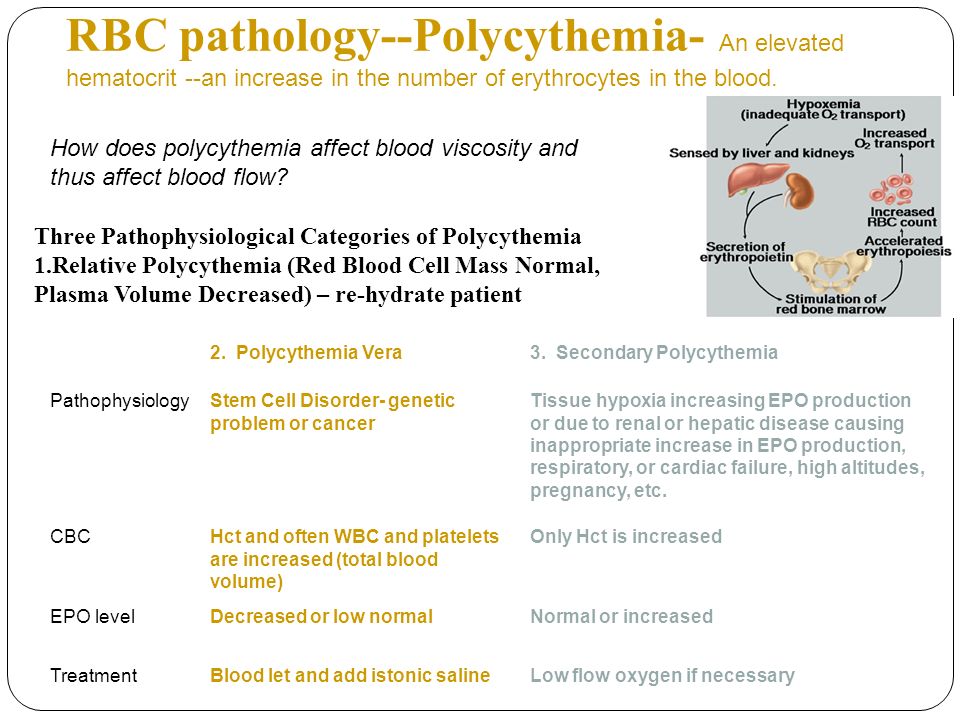

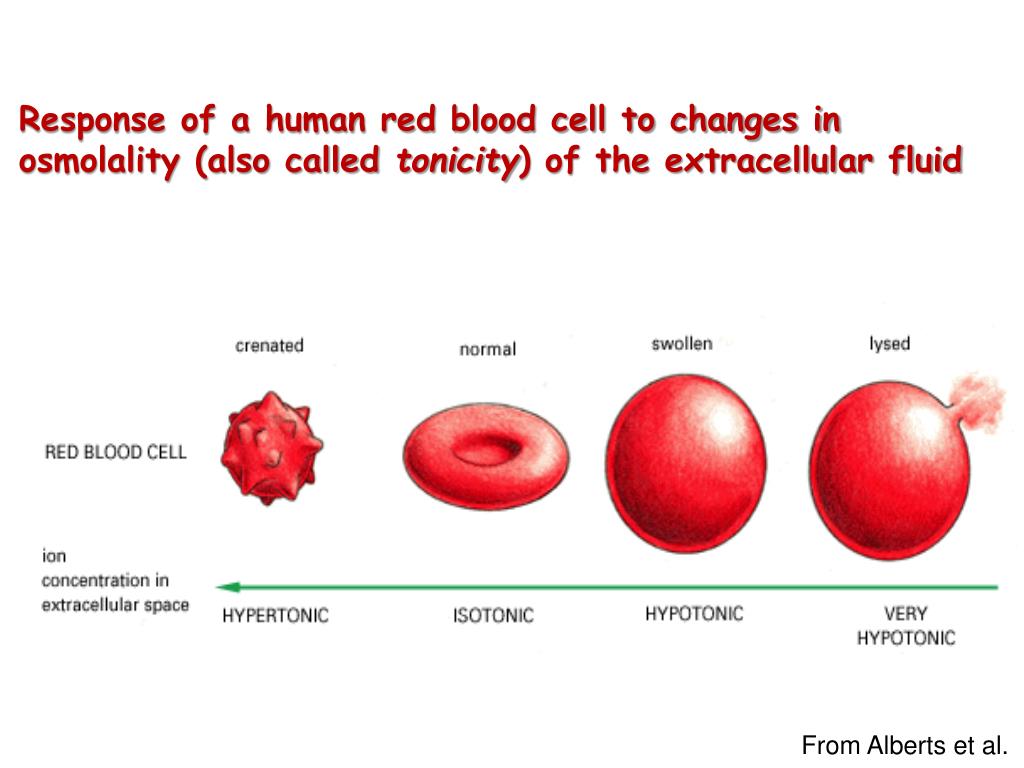

During pregnancy, the total blood volume increases by about 1.5 liters, mainly to supply the demands of the new vascular bed and to compensate for blood loss occurring at delivery [1]. Of this, around one liter of blood is contained within the uterus and maternal blood spaces of the placenta. Increase in blood volume is, therefore, more marked in multiple pregnancies and in iron deficient states. Expansion of plasma volume occurs by 10–15 % at 6–12 weeks of gestation [2, 3]. During pregnancy, plasma renin activity tends to increase and atrial natriuretic peptide levels tend to reduce, though slightly. This suggests that, in pregnant state, the elevation in plasma volume is in response to an underfilled vascular system resulting from systemic vasodilatation and increase in vascular capacitance, rather than actual blood volume expansion, which would produce the opposite hormonal profile instead (i.e., low plasma renin and elevated atrial natriuretic peptide levels) [4, 5].

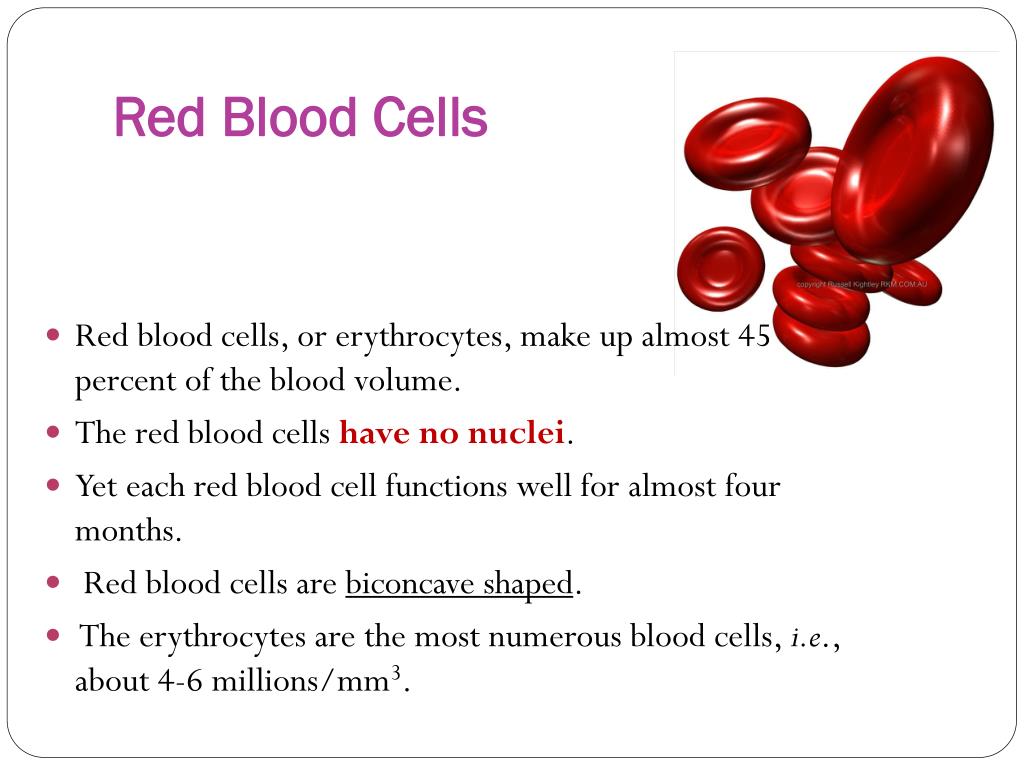

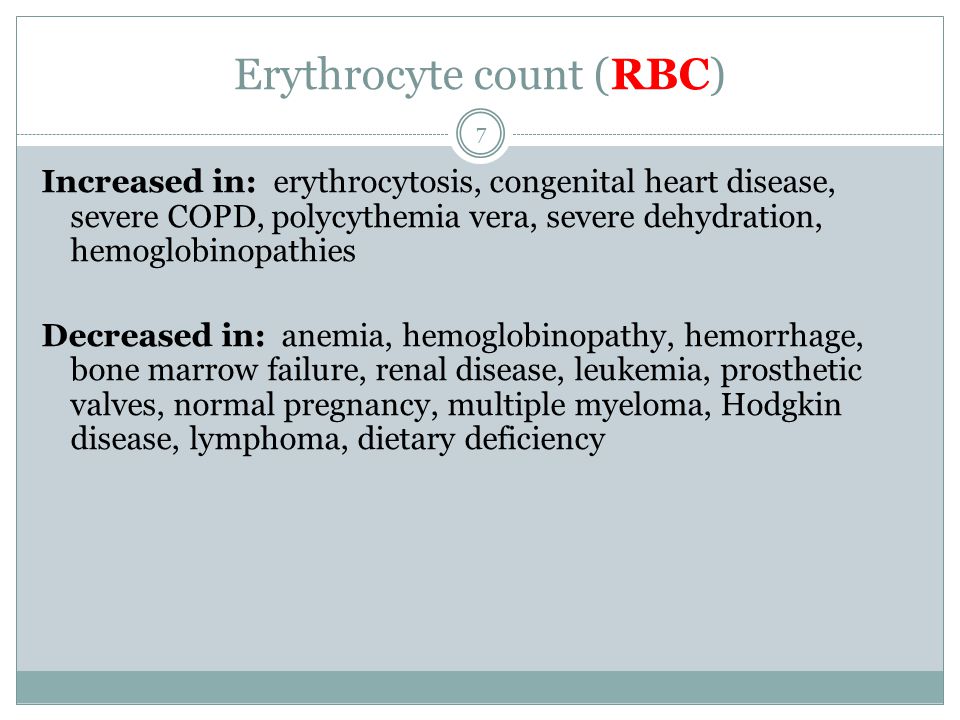

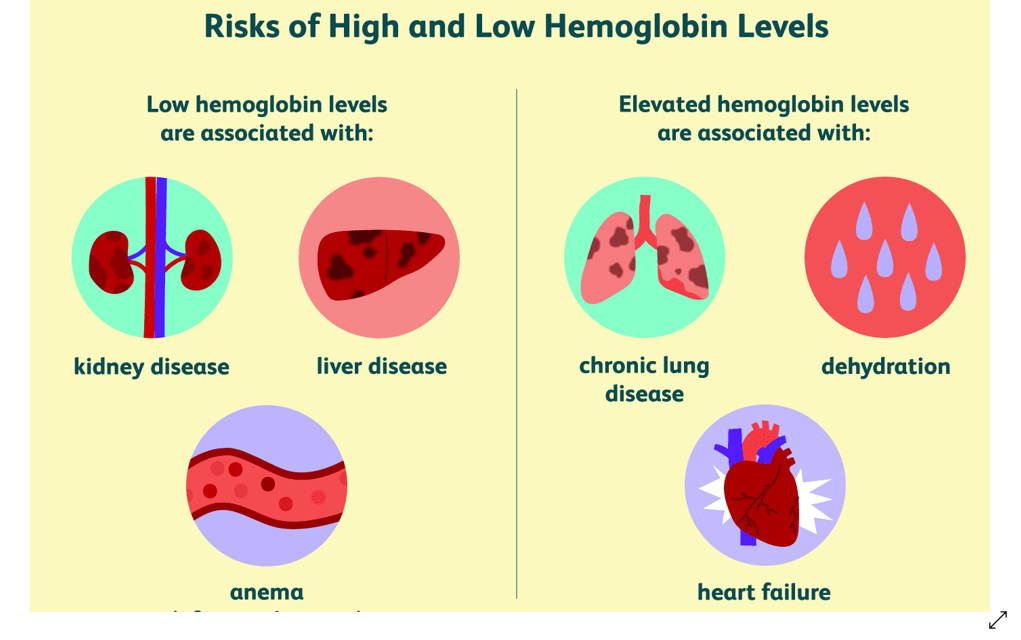

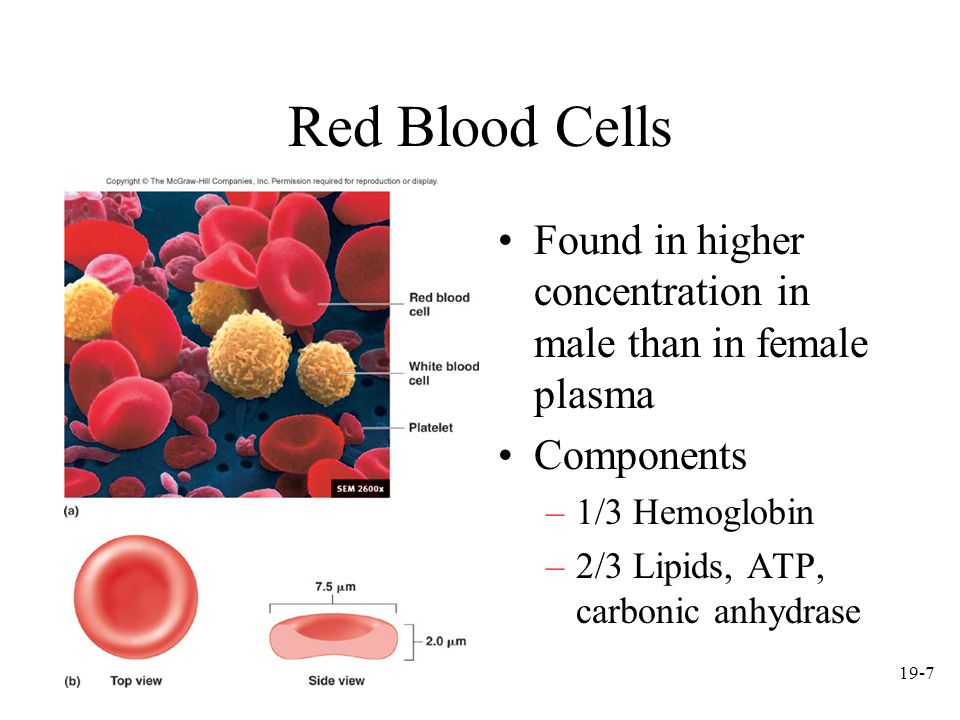

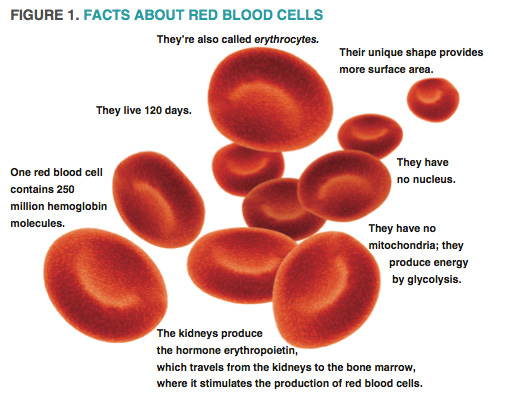

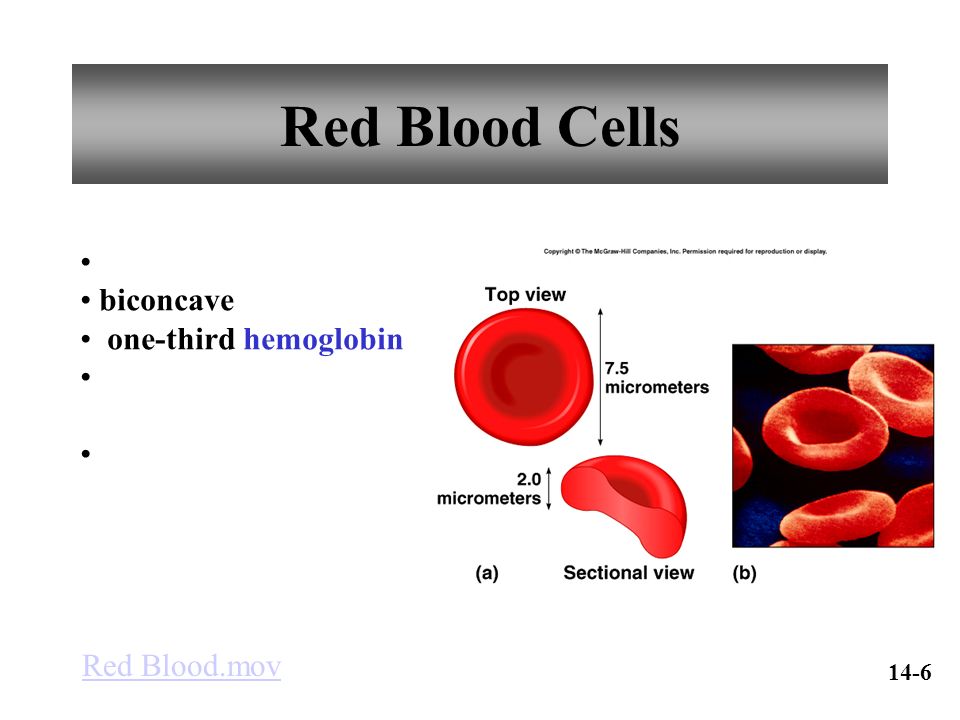

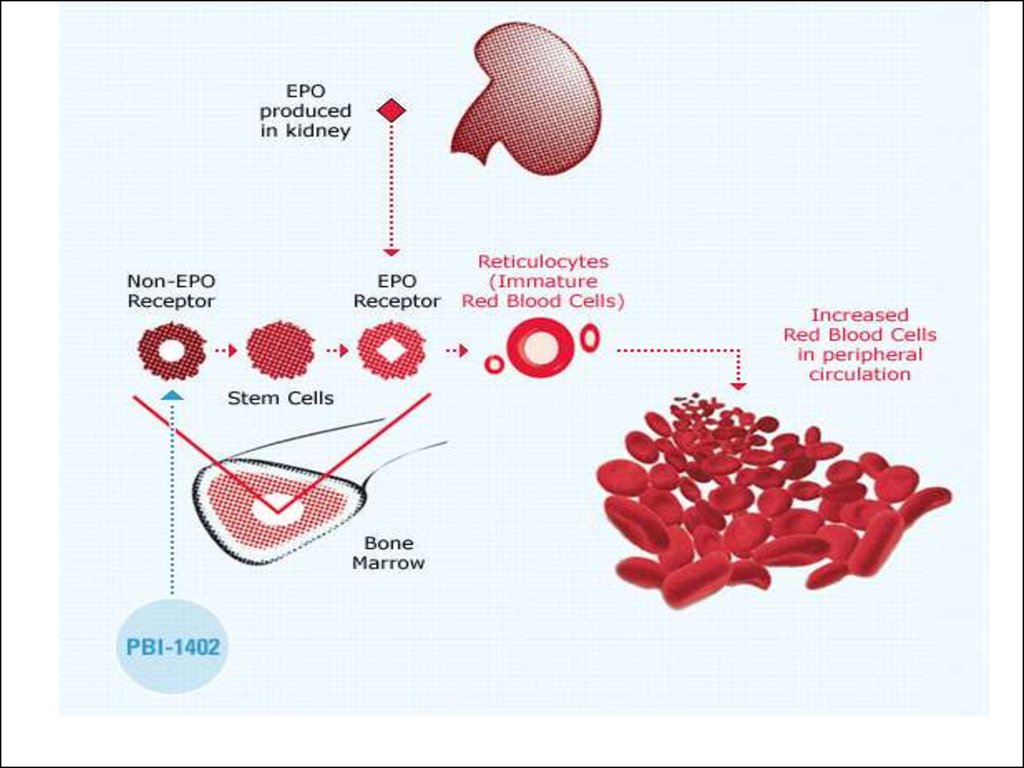

Red cell mass (driven by an increase in maternal erythropoietin production) also increases, but relatively less, compared with the increase in plasma volume, the net result being a dip in hemoglobin concentration. Thus, there is dilutional anemia. The drop in hemoglobin is typically by 1–2 g/dL by the late second trimester and stabilizes thereafter in the third trimester, when there is a reduction in maternal plasma volume (owing to an increase in levels of atrial natriuretic peptide). Women who take iron supplements have less pronounced changes in hemoglobin, as they increase their red cell mass in a more proportionate manner than those not on hematinic supplements.

Thus, there is dilutional anemia. The drop in hemoglobin is typically by 1–2 g/dL by the late second trimester and stabilizes thereafter in the third trimester, when there is a reduction in maternal plasma volume (owing to an increase in levels of atrial natriuretic peptide). Women who take iron supplements have less pronounced changes in hemoglobin, as they increase their red cell mass in a more proportionate manner than those not on hematinic supplements.

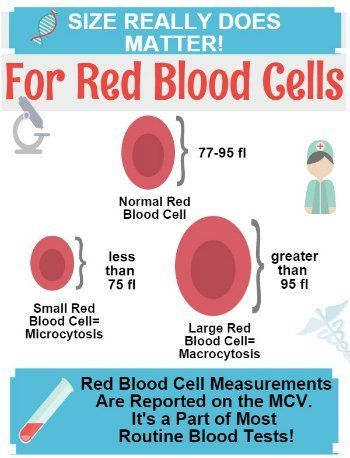

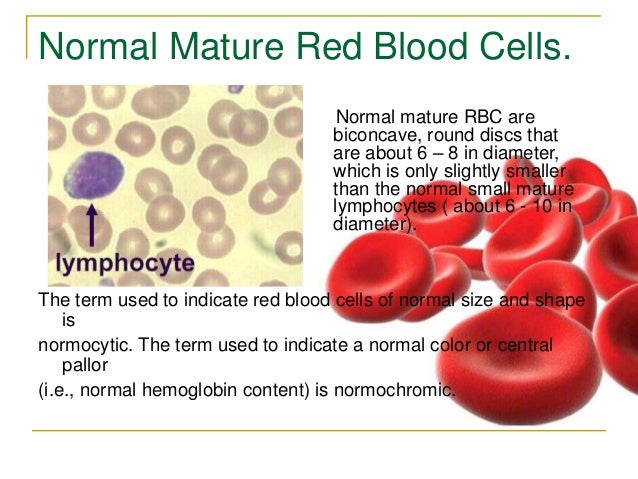

The red blood cell indices change little in pregnancy. However, there is a small increase in mean corpuscular volume (MCV), of an average of 4 fl in an iron-replete woman, which reaches a maximum at 30–35 weeks gestation and does not suggest any deficiency of vitamins B12 and folate. Increased production of RBCs to meet the demands of pregnancy, reasonably explains why there is an increased MCV (due to a higher proportion of young RBCs which are larger in size). However, MCV does not change significantly during pregnancy and a hemoglobin concentration <9. 5 g/dL in association with a mean corpuscular volume <84 fl probably indicates co-existent iron deficiency or some other pathology [6].

5 g/dL in association with a mean corpuscular volume <84 fl probably indicates co-existent iron deficiency or some other pathology [6].

Post pregnancy, plasma volume decreases as a result of diuresis, and the blood volume returns to non-pregnant values. Hemoglobin and hematocrit increase consequently. Plasma volume increases again two to five days later, possibly because of a rise in aldosterone secretion. Later, it again decreases. Significant elevation has been documented between measurements of hemoglobin taken at 6–8 weeks postpartum and those taken at 4–6 months postpartum, indicating that it takes at least 4–6 months post pregnancy, to restore the physiological dip in hemoglobin to the non-pregnant values [7].

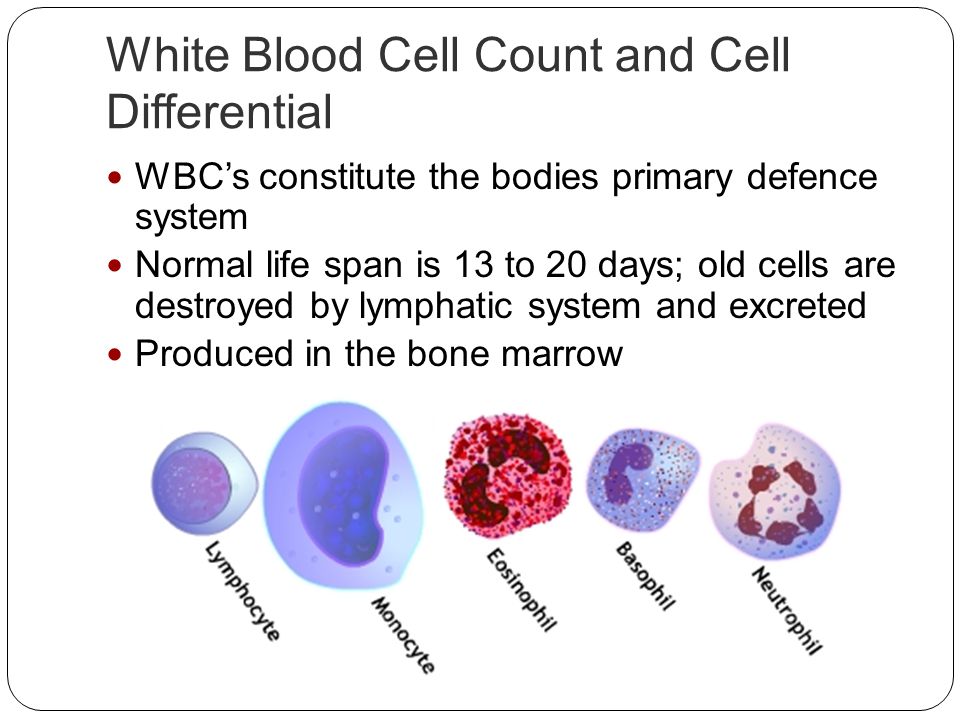

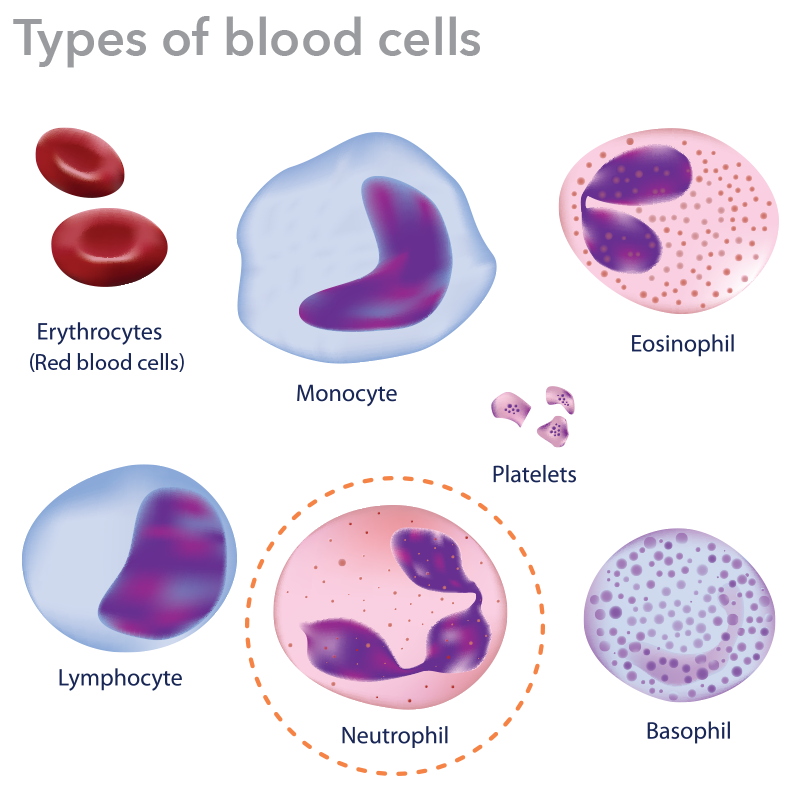

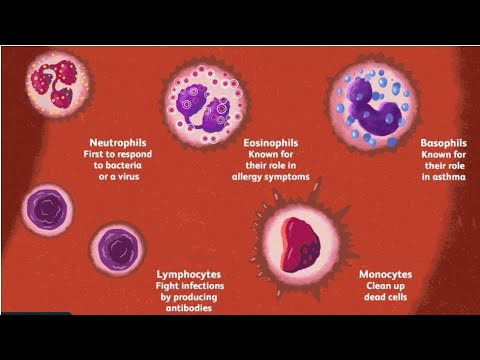

White blood cell count is increased in pregnancy with the lower limit of the reference range being typically 6,000/cumm. Leucocytosis, occurring during pregnancy is due to the physiologic stress induced by the pregnant state [8]. Neutrophils are the major type of leucocytes on differential counts [9, 10]. This is likely due to impaired neutrophilic apoptosis in pregnancy [9]. The neutrophil cytoplasm shows toxic granulation. Neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic activity are depressed, especially due to inhibitory factors present in the serum of a pregnant female [11]. There is also evidence of increased oxidative metabolism in neutrophils during pregnancy. Immature forms as myelocytes and metamyelocytes may be found in the peripheral blood film of healthy women during pregnancy and do not have any pathological significance [12]. They simply indicate adequate bone marrow response to an increased drive for erythropoesis occurring during pregnancy.

This is likely due to impaired neutrophilic apoptosis in pregnancy [9]. The neutrophil cytoplasm shows toxic granulation. Neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic activity are depressed, especially due to inhibitory factors present in the serum of a pregnant female [11]. There is also evidence of increased oxidative metabolism in neutrophils during pregnancy. Immature forms as myelocytes and metamyelocytes may be found in the peripheral blood film of healthy women during pregnancy and do not have any pathological significance [12]. They simply indicate adequate bone marrow response to an increased drive for erythropoesis occurring during pregnancy.

Lymphocyte count decreases during pregnancy through the first and second trimesters and increases during the third trimester. There is an absolute monocytosis during pregnancy, especially in the first trimester, but decreases as gestation advances. Monocytes help in preventing fetal allograft rejection by infiltrating the decidual tissue (7th–20th week of gestation) possibly, through PGE2 mediated immunosuppression [13]. The monocyte to lymphocyte ratio is markedly increased in pregnancy. Eosinophil and basophil counts, however, do not change significantly during pregnancy [14].

The monocyte to lymphocyte ratio is markedly increased in pregnancy. Eosinophil and basophil counts, however, do not change significantly during pregnancy [14].

The stress of delivery may itself lead to brisk leucocytosis. Few hours after delivery, healthy women have been documented as having a WBC count varying from 9,000 to 25,000/cumm. By 4 weeks post-delivery, typical WBC ranges are similar to those in healthy non-pregnant women.

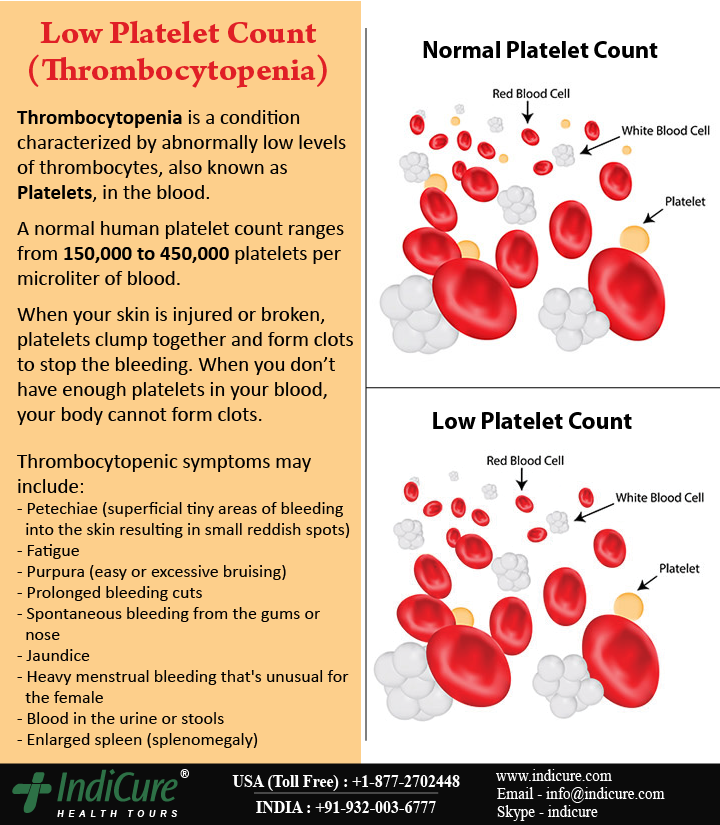

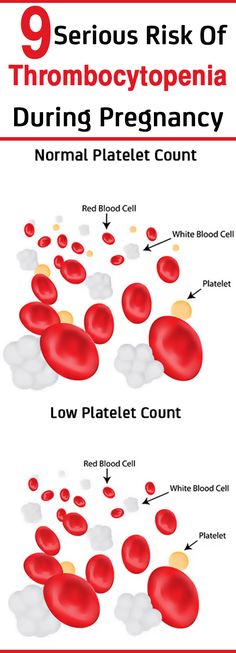

Large cross-sectional studies done in pregnancy of healthy women (specifically excluding any with hypertension) have shown that the platelet count does decrease during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester. This is termed as “gestational thrombocytopenia.” It is partly due to hemodilution and partly due to increased platelet activation and accelerated clearance [15]. Gestational thrombocytopenia does not have complications related to thrombocytopenia and babies do not have severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count ≤20,000/cumm). It has hence been recommended that the lower limit of platelet count in late pregnancy should be considered as 1. 15 lac/cumm [1]. The platelet volume distribution width increases significantly and continuously as gestation advances, for reasons cited before. Thus, with advancing gestation, the mean platelet volume becomes an insensitive measure of the platelet size.

15 lac/cumm [1]. The platelet volume distribution width increases significantly and continuously as gestation advances, for reasons cited before. Thus, with advancing gestation, the mean platelet volume becomes an insensitive measure of the platelet size.

Post delivery platelet count increases in reaction to and as a compensation for increased platelet consumption during the process of delivery.

Pregnancy is associated with significant changes in the hemostatic profile. Fibrinogen and clotting factors VII, VIII, X, XII, vWF and ristocetin co-factor activity increase remarkably as gestation progresses. Increased levels of coagulation factors are due to increased protein synthesis mediated by the rising estrogen levels. In in vitro experiments, pregnant plasma has been demonstrated to be capable of increased thrombin generation [16]. Thus, pregnancy is a prothrombotic state. In pregnancy, aPTT is usually shortened, by up to 4 s in the third trimester, largely due to the hormonally influenced increase in factor VIII. However, no marked changes in PT or TT occur [1].

However, no marked changes in PT or TT occur [1].

There are changes in the levels and activity of the natural anticoagulants also. Levels and activity of Protein C do not change and remain within the same range as for non-pregnant women of similar age. Levels of total and free (i.e., biologically available) Protein S, decrease progressively with the advancement of gestation. Antithrombin levels and activity are usually stable throughout the pregnancy, fall during labor and rise again soon after delivery. Acquired activated Protein C (APC) resistance has been found to occur in pregnancy, even when Factor V Leiden and antiphospholipid antibodies are not present. [18]. This has been attributed to the high factor VIII and factor V activity and low free Protein S levels. Hence, APC sensitivity ratio does not serve as a screening test for Factor V Leiden during pregnancy.

Coagulation factors remain elevated for up to 8–12 weeks post partum and assays for them may be falsely negative during this period.

Markers of hemostatic activity which are clinically relevant are thrombin–antithrombin complexes (TAT) and prothrombin fragments (F 1 + 2), which reflect in vivo thrombin formation, as also, tests which demonstrate plasmin degradation of fibrin polymer to yield fragments, namely D-dimer and fibrin degradation products (FDP) assay. TAT levels increase with gestation; in early pregnancy the upper limit of normal is similar to the adult range of 2.63 g/L, whereas by term, the upper limit of normal is 18.03 g/L. D-dimer levels are markedly increased in pregnancy, with typical reference range being tenfold higher in late pregnancy than in early pregnancy or in the nonpregnant state [1]. The increase in D-dimers reflects the overall increase in total amount of fibrin during pregnancy consequent to increased thrombin generation, increased fibrinolysis or a combination of both [17]. This also explains why the D-dimer assay is not reliable for predicting the possibility of venous thrombo-embolism in pregnant patients [13].

1. Ramsay Margaret. Normal hematological changes during pregnancy and the puerperium. In: Pavord S, Hunt B, editors. The obstetric hematology manual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

2. Bernstein IM, Ziegler W, Badger GJ. Plasma volume expansion in early pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:669. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01222-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Bjorksten B, Soderstrom T, Damber M-G, Schoultz B, Stigbrand T. Polymorphonuclear leucocyte function during pregnancy. Scand J Immunol. 1978;8(3):257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1978.tb00518.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Ajzenberg N, Dreyfus M, Kaplan C, Yvart J, Weill B, Tchernia G. Pregnancy-associated thrombocytopenia revisited: assessment and follow-up of 50 cases. Blood. 1998;92(12):4573–4580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Barriga C, Rodriguez AB, Orega E. Increased phagocytic activity of polymorphonuclear leucocytes during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;57(1):43–46. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90109-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;57(1):43–46. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90109-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Crocker IP, Baker PN, Fletcher J. Neutrophil function in pregnancy and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheumat Dis. 2000;59:555–564. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.7.555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Taylor DJ, Lind T. Red cell mass during and after normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;86:364–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1979.tb10611.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Fleming AF. Hematological changes in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1975;2:269. [Google Scholar]

9. Gatti L, Tinconi PM, Guarneri D, Bertuijessi C, Ossola MW, Bosco P, Gianotti G. Hemostatic parameters and platelet activation by flow-cytometry in normal pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Internat J Clin Lab Res. 1994;24(4):217–219. doi: 10.1007/BF02592466. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Konijnenberg A, Stokkers E, Post J. Extensive platelet activation in preeclampsia compared with normal pregnancy: enhanced expression of cell adhesion molecules. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(2):461–469. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70516-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(2):461–469. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70516-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Jessica M, Badger F, Hseih CC, Troisi R, Lagiou P, Polischman N. Plasma volume expansion in pregnancy: implications for biomarkers in population studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers. 2007;16:1720. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0311. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Karalis L, Nadan S, Yemen EA. Platelet activation in pregnancy induced hypertension. Thromb Res. 2005;116(5):377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.01.009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Kline AJ, Williams GW, Hernandez-Nino J. D-Dimer concentration in normal pregnancy: new diagnostic thresholds are needed. Clin Chem. 2005;51(5):825–829. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.044883. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Edlestam G, Lowbeer C, Kral G, et al. New reference values for routine blood samples and human neutrophilic lipocalin during third trimester pregnancy. Scand J Clin Lab Inv. 2001;61:583–592. doi: 10.1080/003655101753267937. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2001;61:583–592. doi: 10.1080/003655101753267937. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Shehlata N, Burrows RF, Kelton JG. Gestational thrombocytopenia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42:327–334. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199906000-00017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Boer K, Cate JW, Sturk A, Borm JJ, Treffers PE. Enhanced thrombin generation in normal and hypertensive pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(1):95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Eichinger S. D-dimer testing in pregnancy. Pathophysiol Hemost Thromb. 2004;33:327–329. doi: 10.1159/000083822. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Clark P, Brennard J, Conkie JA, et al. Activated protein C sensitivity, protein C, protein S and coagulation in normal pregnancy. Thromb Hemost. 1998;79:1166–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anemia in Pregnancy: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Written by Jen Uscher

Reviewed by Traci C. Johnson, MD on August 12, 2022

In this Article

- Types of Anemia During Pregnancy

- Risk Factors for Anemia in Pregnancy

- Symptoms of Anemia During Pregnancy

- Risks of Anemia in Pregnancy

- Tests for Anemia

- Treatment for Anemia

- Preventing Anemia

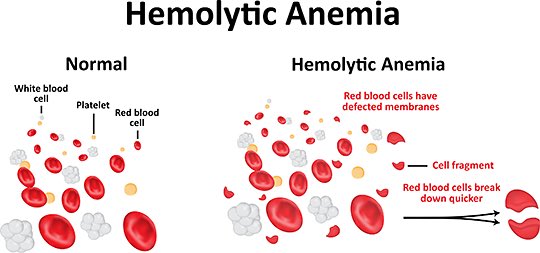

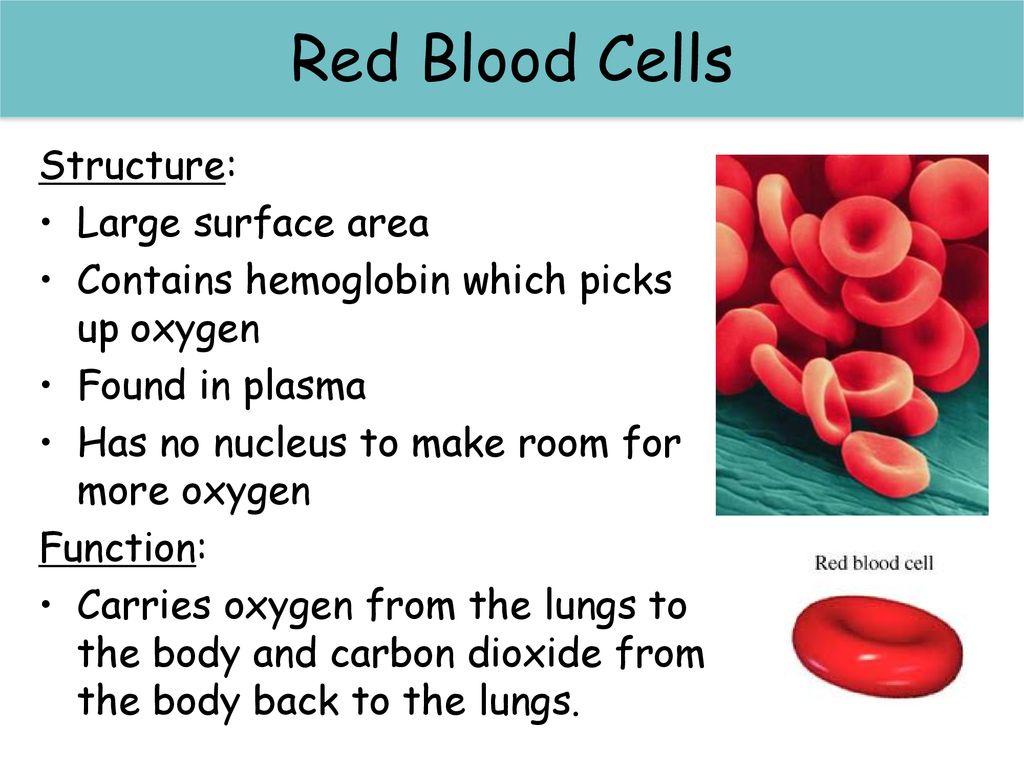

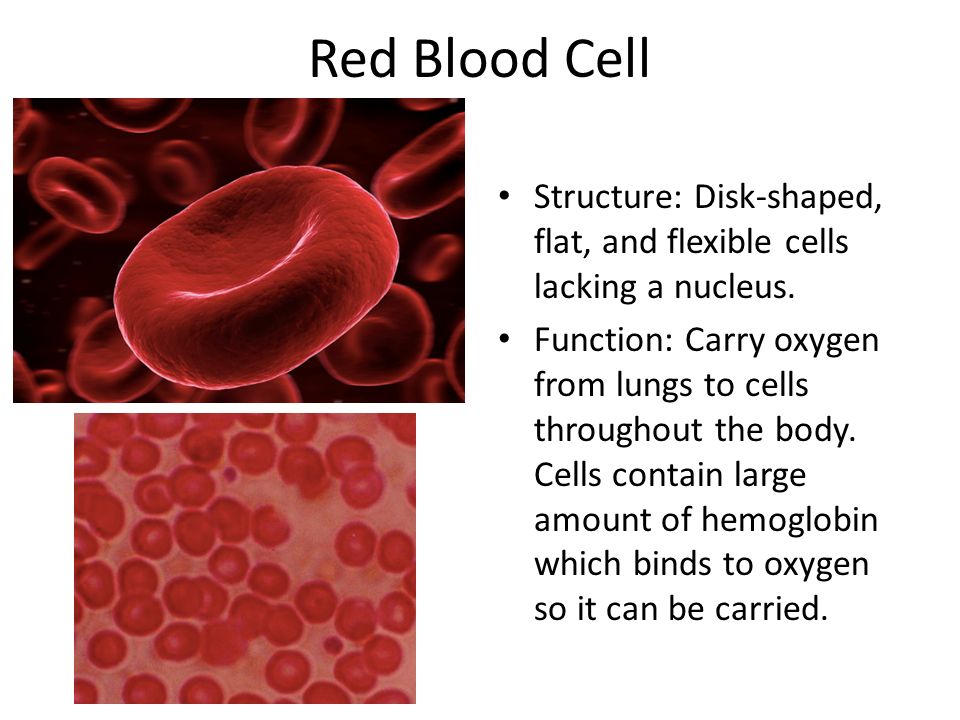

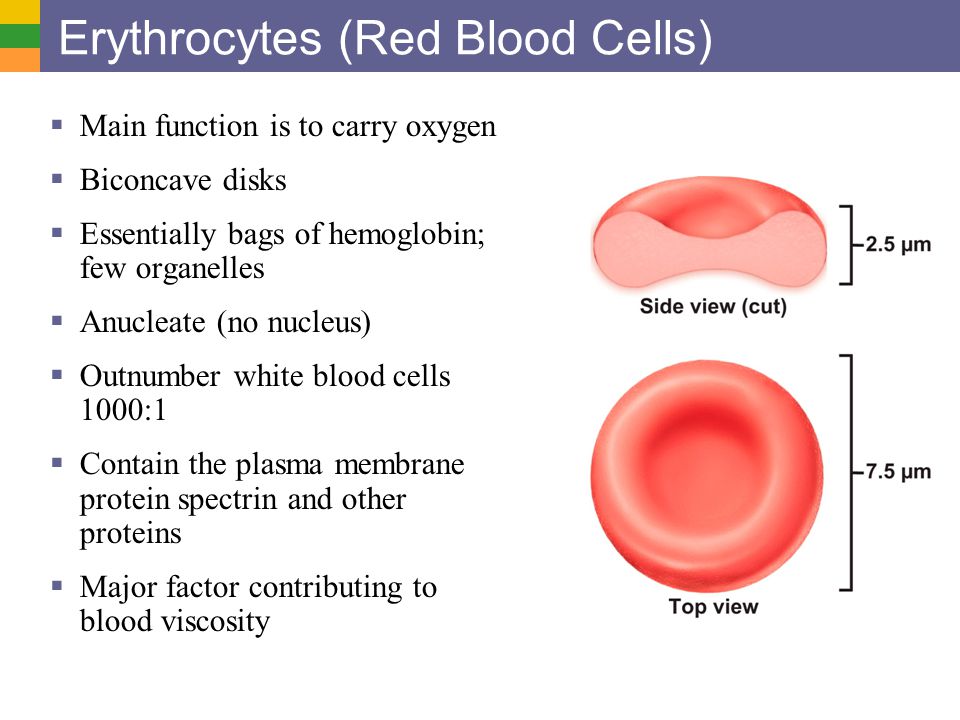

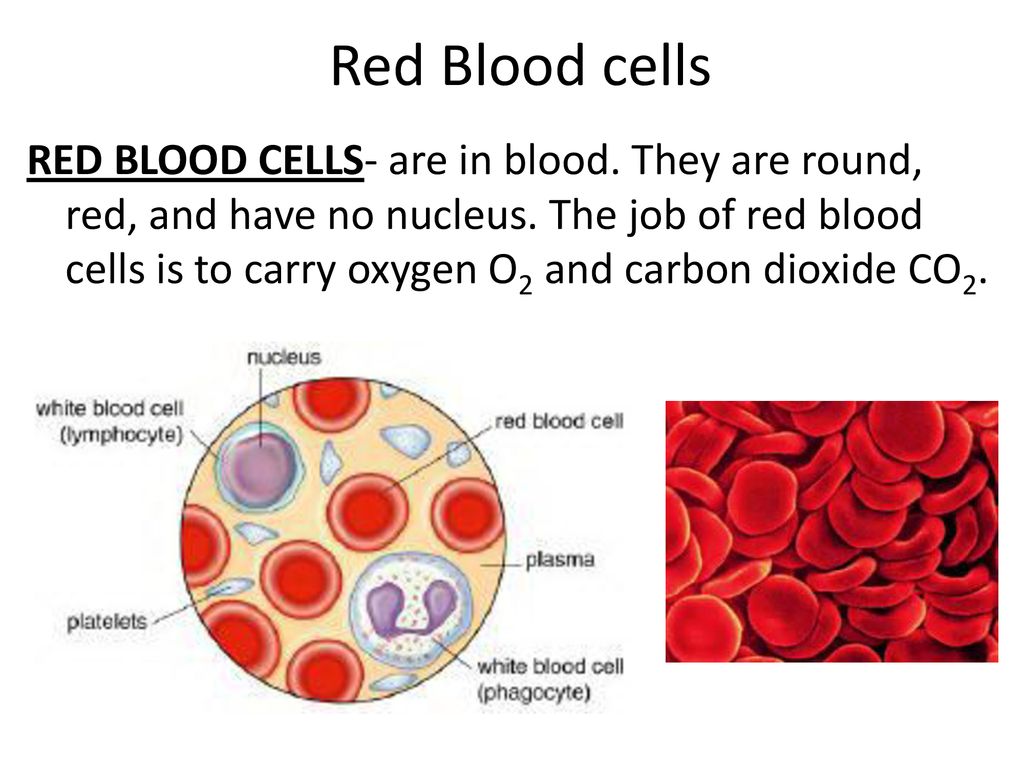

When you're pregnant, you may develop anemia. When you have anemia, your blood doesn't have enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen to your tissues and to your baby.

When you have anemia, your blood doesn't have enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen to your tissues and to your baby.

During pregnancy, your body produces more blood to support the growth of your baby. If you're not getting enough iron or certain other nutrients, your body might not be able to produce the amount of red blood cells it needs to make this additional blood.

It's normal to have mild anemia when you are pregnant. But you may have more severe anemia from low iron or vitamin levels or from other reasons.

Anemia can leave you feeling tired and weak. If it is severe but goes untreated, it can increase your risk of serious complications like preterm delivery.

Here's what you need to know about the causes, symptoms, and treatment of anemia during pregnancy.

Types of Anemia During Pregnancy

Several types of anemia can develop during pregnancy. These include:

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Folate-deficiency anemia

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

Here's why these types of anemia may develop:

Iron-deficiency anemia. This type of anemia occurs when the body doesn't have enough iron to produce adequate amounts of hemoglobin. That's a protein in red blood cells. It carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

This type of anemia occurs when the body doesn't have enough iron to produce adequate amounts of hemoglobin. That's a protein in red blood cells. It carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

In iron-deficiency anemia, the blood cannot carry enough oxygen to tissues throughout the body.

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia in pregnancy.

Folate-deficiency anemia. Folate is the vitamin found naturally in certain foods like green leafy vegetables A type of B vitamin, the body needs folate to produce new cells, including healthy red blood cells.

During pregnancy, women need extra folate. But sometimes they don't get enough from their diet. When that happens, the body can't make enough normal red blood cells to transport oxygen to tissues throughout the body. Man made supplements of folate are called folic acid.

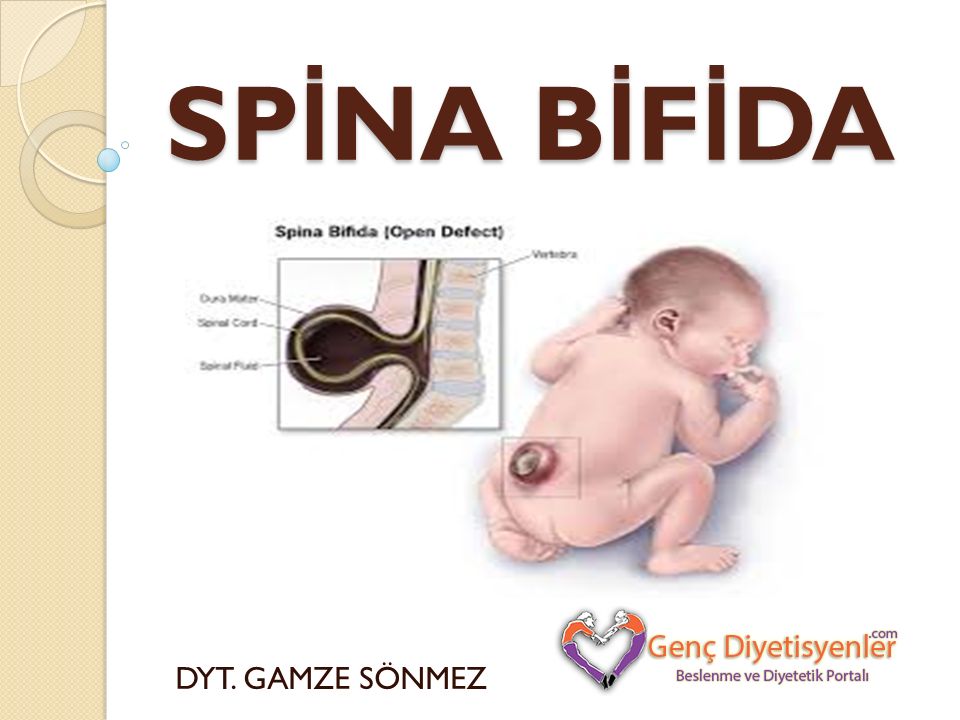

Folate deficiency can directly contribute to certain types of birth defects, such as neural tube abnormalities (spina bifida) and low birth weight.

Vitamin B12 deficiency. The body needs vitamin B12 to form healthy red blood cells. When a pregnant woman doesn't get enough vitamin B12 from their diet, their body can't produce enough healthy red blood cells. Women who don't eat meat, poultry, dairy products, and eggs have a greater risk of developing vitamin B12 deficiency, which may contribute to birth defects, such as neural tube abnormalities, and could lead to preterm labor.

Blood loss during and after delivery can also cause anemia.

Risk Factors for Anemia in Pregnancy

All pregnant women are at risk for becoming anemic. That's because they need more iron and folic acid than usual. But the risk is higher if you:

- Are pregnant with multiples (more than one child)

- Have had two pregnancies close together

- Vomit a lot because of morning sickness

- Are a pregnant teenager

- Don't eat enough foods that are rich in iron

- Had anemia before you became pregnant

Symptoms of Anemia During Pregnancy

The most common symptoms of anemia during pregnancy are:

- Pale skin, lips, and nails

- Feeling tired or weak

- Dizziness

- Shortness of breath

- Rapid heartbeat

- Trouble concentrating

In the early stages of anemia, you may not have obvious symptoms. And many of the symptoms are ones that you might have while pregnant even if you're not anemic. So be sure to get routine blood tests to check for anemia at your prenatal appointments.

And many of the symptoms are ones that you might have while pregnant even if you're not anemic. So be sure to get routine blood tests to check for anemia at your prenatal appointments.

Risks of Anemia in Pregnancy

Severe or untreated iron-deficiency anemia during pregnancy can increase your risk of having:

- A preterm or low-birth-weight baby

- A blood transfusion (if you lose a significant amount of blood during delivery)

- Postpartum depression

- A baby with anemia

- A child with developmental delays

Untreated folate deficiency can increase your risk of having a:

- Preterm or low-birth-weight baby

- Baby with a serious birth defect of the spine or brain (neural tube defects)

Untreated vitamin B12 deficiency can also raise your risk of having a baby with neural tube defects.

Tests for Anemia

During your first prenatal appointment, you'll get a blood test so your doctor can check whether you have anemia. Blood tests typically include:

Blood tests typically include:

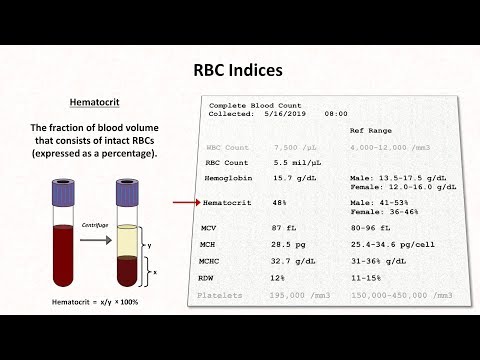

- Hemoglobin test. It measures the amount of hemoglobin -- an iron-rich protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to tissues in the body.

- Hematocrit test. It measures the percentage of red blood cells in a sample of blood.

If you have lower than normal levels of hemoglobin or hematocrit, you may have iron-deficiency anemia. Your doctor may check other blood tests to determine if you have iron deficiency or another cause for your anemia.

Even if you don't have anemia at the beginning of your pregnancy, your doctor will most likely recommend that you get another blood test to check for anemia in your second or third trimester.

Treatment for Anemia

If you are anemic during your pregnancy, you may need to start taking an iron supplement and/or folic acid supplement in addition to your prenatal vitamins. Your doctor may also suggest that you add more foods that are high in iron and folic acid to your diet.

In addition, you'll be asked to return for another blood test after a specific period of time so your doctor can check that your hemoglobin and hematocrit levels are improving.

To treat vitamin B12 deficiency, your doctor may recommend that you take a vitamin B12 supplement.

The doctor may also recommend that you include more animal foods in your diet, such as:

- meat

- eggs

- dairy products

Your OB may refer you to a hematologist, a doctor who specializes in anemia/ blood issues. The specialist may see you throughout the pregnancy and help your OB manage the anemia.

Preventing Anemia

To prevent anemia during pregnancy, make sure you get enough iron. Eat well-balanced meals and add more foods that are high in iron to your diet.

Aim for at least three servings a day of iron-rich foods, such as:

- lean red meat, poultry, and fish

- leafy, dark green vegetables (such as spinach, broccoli, and kale)

- iron-enriched cereals and grains

- beans, lentils, and tofu

- nuts and seeds

- eggs

Foods that are high in vitamin C can help your body absorb more iron. These include:

These include:

- citrus fruits and juices

- strawberries

- kiwis

- tomatoes

- bell peppers

Try eating those foods at the same time that you eat iron-rich foods. For example, you could drink a glass of orange juice and eat an iron-fortified cereal for breakfast.

Also, choose foods that are high in folate to help prevent folate deficiency. These include:

- leafy green vegetables

- citrus fruits and juices

- dried beans

- breads and cereals fortified with folic acid

Follow your doctor's instructions for taking a prenatal vitamin that contains a sufficient amount of iron and folic acid.

Vegetarians and vegans should talk with their doctor about whether they should take a vitamin B12 supplement when they're pregnant and breastfeeding.

Health & Pregnancy Guide

- Getting Pregnant

- First Trimester

- Second Trimester

- Third Trimester

- Labor and Delivery

- Pregnancy Complications

- All Guide Topics

The norm of a complete blood count during pregnancy.

Hemoglobin, platelets, hematocrit, erythrocytes and leukocytes during pregnancy. Clinical blood test during pregnancy. Hematological changes during pregnancy.

Hemoglobin, platelets, hematocrit, erythrocytes and leukocytes during pregnancy. Clinical blood test during pregnancy. Hematological changes during pregnancy. A normal pregnancy is characterized by significant changes in almost all organs and systems to adapt to the requirements of the fetoplacental complex, including changes in blood tests during pregnancy.

Blood test norms during pregnancy: summary of the article

- Significant hematological changes during pregnancy are physiological anemia, neutrophilia, mild thrombocytopenia, increased blood clotting factors and decreased fibrinolysis.

- By 6-12 weeks of gestation, plasma volume increases by approximately 10-15%. The fastest rate of increase in plasma volume occurs between 30 and 34 weeks of gestation, after which plasma volume changes little.

- Red blood cell count begins to increase at 8-10 weeks of gestation and by the end of pregnancy increases by 20-30% (250-450 ml) of the normal level for non-pregnant women by the end of pregnancy A significant increase in plasma volume relative to the increase in hemoglobin and red blood cell volume leads to moderate decrease in hemoglobin levels (physiological anemia of pregnancy), which is observed in healthy pregnant women.

- Pregnant women may have a slightly lower platelet count than healthy non-pregnant women.

- The neutrophil count begins to rise in the second month of pregnancy and stabilizes in the second or third trimester, at which time the white blood cell count. The absolute number of lymphocytes does not change.

- The level of some blood coagulation factors changes during pregnancy.

This article describes the hematological changes that occur during pregnancy, the most important of which are:

- Increased plasma volume and decreased hematocrit

- Physiological anemia, low hemoglobin

- Elevated white blood cells during pregnancy

- Neutrophilia

- Moderate thrombocytopenia

- Increase in procoagulant factors

- Fibrinolysis reduction

Tests mentioned in the article

How to take blood tests and get a 5% discount? Go to the CIR laboratories online store!

Plasma volume

By 6-12 weeks of pregnancy, the volume of blood plasma increases by about 10-15%. The fastest rate of increase in plasma volume occurs between 30 and 34 weeks of gestation, after which plasma volume changes little. On average, plasma volume increases by 1100-1600 ml per trimester, and as a result, plasma volume during pregnancy increases to 4700-5200 ml, which is 30 to 50% higher than plasma volume in non-pregnant women.

The fastest rate of increase in plasma volume occurs between 30 and 34 weeks of gestation, after which plasma volume changes little. On average, plasma volume increases by 1100-1600 ml per trimester, and as a result, plasma volume during pregnancy increases to 4700-5200 ml, which is 30 to 50% higher than plasma volume in non-pregnant women.

During pregnancy, plasma renin activity tends to increase, while the level of atrial natriuretic peptide decreases slightly. This suggests that the increase in plasma volume is caused by insufficiency of the vascular system, which leads to systemic vasodilation (dilation of blood vessels throughout the body) and an increase in vascular capacity. Since it is the volume of blood plasma that initially increases, its effect on the renal and atrial receptors leads to opposite effects on the hormonal background (a decrease in plasma renin activity and an increase in natriuretic peptide). This hypothesis is also supported by the observation that an increase in sodium intake does not lead to a further increase in plasma volume.

Plasma volume immediately decreases after delivery, but rises again 2-5 days later, possibly due to increased aldosterone secretion occurring at this time. Plasma volume then gradually decreases again: 3 weeks postpartum, it is still elevated by 10-15% of the normal level for non-pregnant women, but usually returns to normal by 6 weeks postpartum.

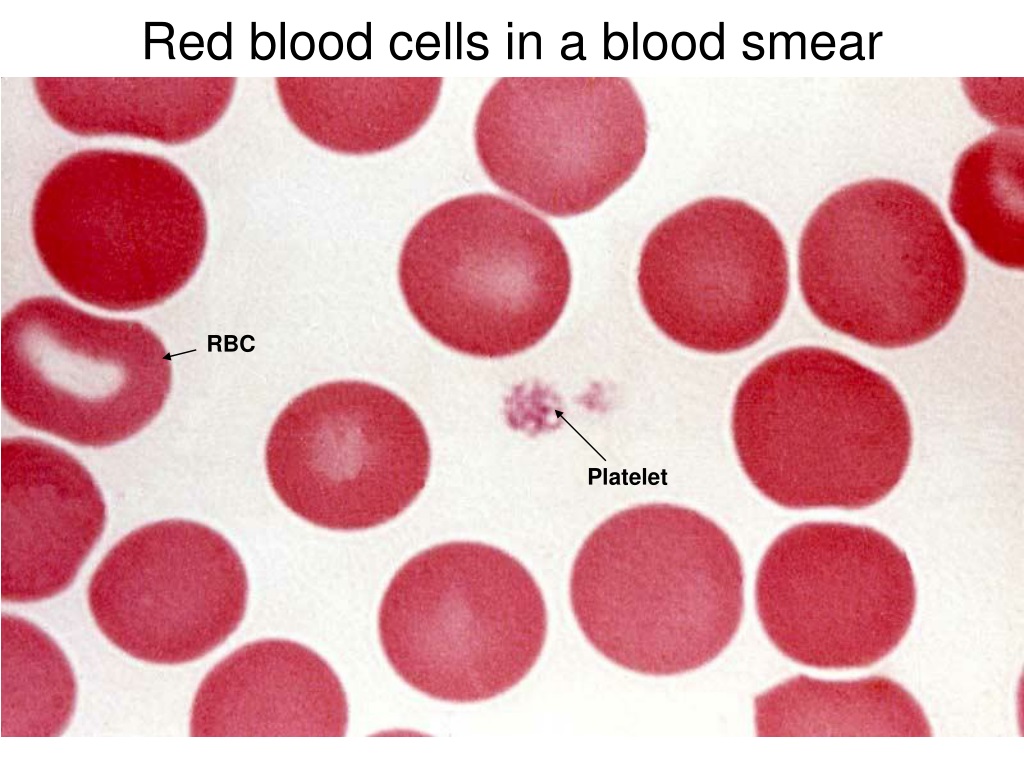

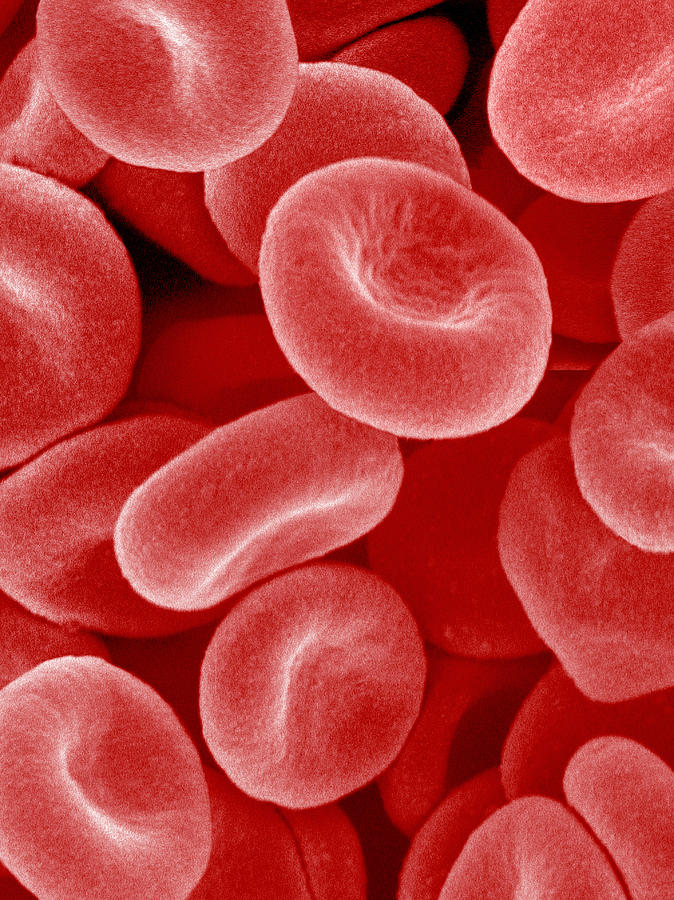

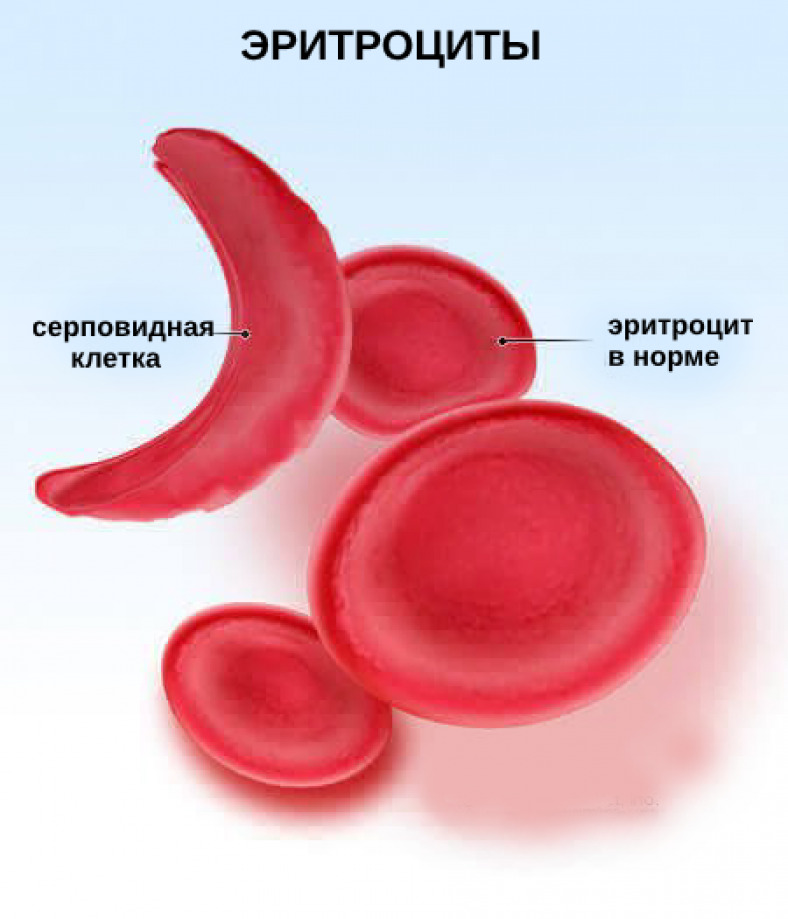

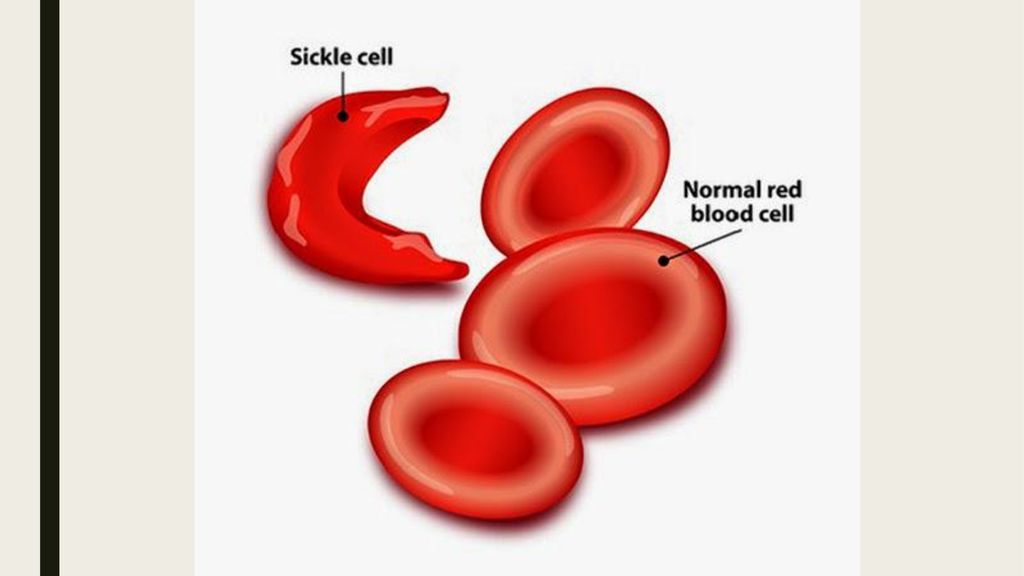

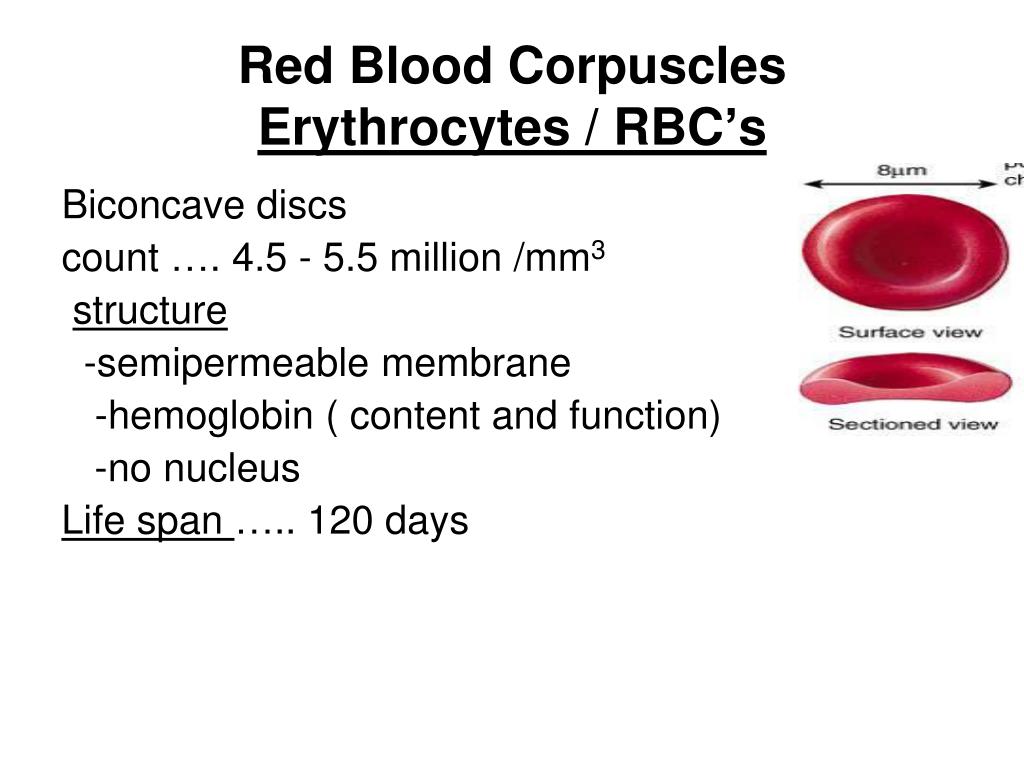

Red blood cells during pregnancy, ESR during pregnancy

The number of red blood cells begins to increase at 8-10 weeks of gestation and by the end of pregnancy increases by 20-30% (250-450 ml) of the normal level for non-pregnant women, especially in women taking drugs iron during pregnancy. Among pregnant women who did not take iron supplements, the number of red blood cells may increase by only 15-20%. The lifespan of red blood cells decreases slightly during a normal pregnancy.

The level of erythropoietin during normal pregnancy increases by 50% and its change depends on the presence of pregnancy complications. An increase in plasma erythropoietin leads to an increase in the number of red blood cells, which partially provide for the high metabolic oxygen requirements during pregnancy.

An increase in plasma erythropoietin leads to an increase in the number of red blood cells, which partially provide for the high metabolic oxygen requirements during pregnancy.

In women not taking iron supplements, mean red cell volume decreases during pregnancy and averages 80-84 fl in the third trimester. However, in healthy pregnant women and in pregnant women with moderate iron deficiency, the average volume of erythrocytes increases by about 4 fl.

ESR increases during pregnancy, which has no diagnostic value.

Anemia in pregnancy, hemoglobin in pregnancy, hematocrit in pregnancy, low hemoglobin in pregnancy

Decreased hemoglobin in pregnancy

pregnant), which is observed in healthy pregnant women. The biggest difference between the growth rate of blood plasma volume and the number of red blood cells in the maternal circulation is formed during the end of the second, beginning of the third trimester (a decrease in hemoglobin usually occurs at 28-36 weeks of pregnancy). The hemoglobin concentration rises due to the cessation of the increase in plasma volume and the continuation of the increase in the amount of hemoglobin. Conversely, the absence of physiological anemia is a risk factor for stillbirth.

The hemoglobin concentration rises due to the cessation of the increase in plasma volume and the continuation of the increase in the amount of hemoglobin. Conversely, the absence of physiological anemia is a risk factor for stillbirth. Anemia in pregnancy

Defining anemia in pregnant women is difficult because it consists of pregnancy-related changes in plasma volume and red blood cell count, physiological differences in hemoglobin concentration between women and men, and the frequency of iron supplementation during pregnancy.

- The Centers for Disease Prevention and Control defined anemia as hemoglobin levels less than 110 g/L (hematocrit less than 33%) in the first and third trimesters and less than 105 g/L (hematocrit less than 32%) in the second trimester.

- WHO defined anemia in pregnancy as a decrease in hemoglobin less than 110 g/l (11 g/dl) or hematocrit less than 6.83 mmol/l or 33%. Severe anemia in pregnancy is determined by a hemoglobin level of less than 70 g/l and needs medical treatment.

Very severe anemia is defined as a hemoglobin level of less than 40 g/L and is a medical emergency due to the risk of congestive heart failure.

Very severe anemia is defined as a hemoglobin level of less than 40 g/L and is a medical emergency due to the risk of congestive heart failure.

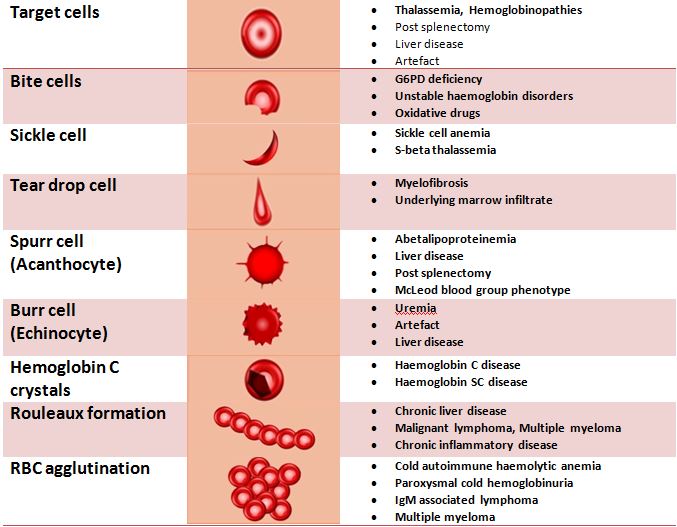

Women with hemoglobin values below these levels are considered anemic and should undergo routine tests (CBC with peripheral blood smear evaluation, reticulocyte count, serum iron, ferritin, transferrin). If no abnormalities were detected during the examination, then hemoglobin reduced to a level of 100 g / l can be considered physiological anemia with a wide variety of factors affecting the normal level of hemoglobin in a particular person.

Chronic severe anemia is most common among women in developing countries. A decrease in maternal hemoglobin below 60 g / l leads to a decrease in the volume of amniotic fluid, vasodilation of the cerebral vessels of the fetus and a change in the heart rate of the fetus. It also increases the risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, low birth weight and stillbirth. In addition, severe anemia (hemoglobin less than 70 g/l) increases the risk of maternal death. There is no evidence that anemia increases the risk of congenital malformations of the fetus.

There is no evidence that anemia increases the risk of congenital malformations of the fetus.

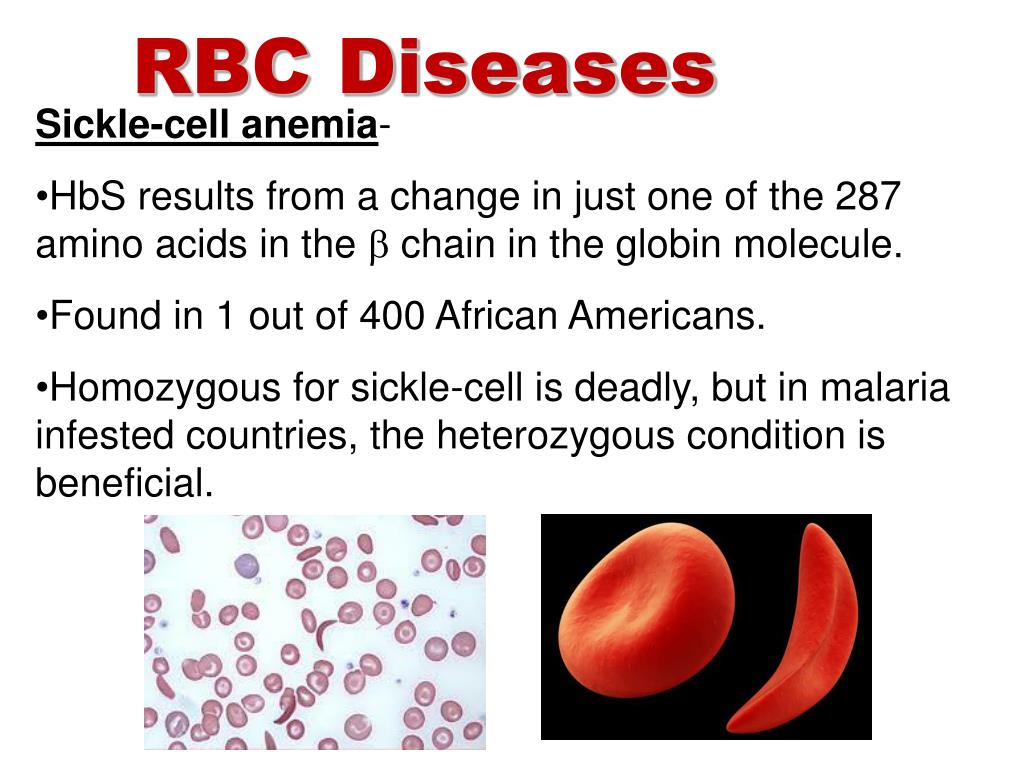

Severe chronic anemia is usually associated with insufficient iron stores (due to insufficient dietary intake or intestinal worm infestations), folate deficiency (due to insufficient intake and chronic hemolytic conditions such as malaria). Thus, prevention of chronic anemia and improvement of pregnancy outcome is possible with the use of nutritional supplements and the use of infection control measures.

Administering blood and packed red cell transfusions (where safe blood transfusion is available) is a reasonable aggressive treatment for severe anemia, especially if there are signs of fetal hypoxia.

Signs of physiological anemia of pregnancy disappear 6 weeks after delivery, when plasma volume returns to normal.

Iron requirement

In a singleton pregnancy, the iron requirement is 1000 mg per pregnancy: approximately 300 mg for the fetus and placenta and approximately 500 mg, if any, to increase hemoglobin. 200 mg is lost through the intestines, urine and skin. Since most women do not have an adequate supply of iron to meet their needs during pregnancy, iron is usually prescribed as part of a multivitamin, or as a separate element. In general, women taking iron supplements have a 1 g/dL higher hemoglobin concentration than women not taking iron.

200 mg is lost through the intestines, urine and skin. Since most women do not have an adequate supply of iron to meet their needs during pregnancy, iron is usually prescribed as part of a multivitamin, or as a separate element. In general, women taking iron supplements have a 1 g/dL higher hemoglobin concentration than women not taking iron.

Folate requirements

The daily folate requirement for non-pregnant women is 50-100 micrograms. An increase in the number of red blood cells during pregnancy leads to an increase in the need for folic acid, which is provided by increasing the dose of folic acid to 400-800 mcg per day, to prevent neural tube defects in the fetus.

Platelets during pregnancy

In most cases, the platelet count during uncomplicated pregnancy remains within the normal range for non-pregnant women, but it is also possible for pregnant women to have lower platelet counts compared to healthy non-pregnant women. The platelet count begins to rise immediately after childbirth and continues to increase for 3-4 weeks until it returns to normal values.

Thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

The most important obstetrical change in platelet physiology during pregnancy is thrombocytopenia, which may be associated with pregnancy complications (severe preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome), drug disorders (immune thrombocytopenia) or may be gestational thrombocytopenia.

Gestational or occasional thrombocytopenia is asymptomatic in the third trimester of pregnancy in patients without prior thrombocytopenia. It is not associated with maternal, fetal, or neonatal complications and resolves spontaneously after delivery. 99/l. The white blood cell count drops to the reference range for non-pregnant women by the sixth day after delivery.

Pregnant women may have a small number of myelocytes and metamyelocytes in the peripheral blood. According to some studies, there is an increase in the number of young forms of neutrophils during pregnancy. Lobe bodies (blue staining of cytoplasmic inclusions in granulocytes) are considered normal in pregnant women.

In healthy women during uncomplicated pregnancy, there is no change in the absolute number of lymphocytes and there are no significant changes in the relative number of T- and B-lymphocytes. The number of monocytes usually does not change, the number of basophils may decrease slightly, and the number of eosinophils may increase slightly.

Coagulation factors and inhibitors

During normal pregnancy, the following changes in clotting factor levels occur, leading to physiological hypercoagulability:

- Due to hormonal changes during pregnancy, the activity of total protein S antigen, free protein S antigen and protein S is reduced.

- Activated protein C resistance increases in the second and third trimesters. These changes have been identified in first-generation tests using pure blood plasma (i.e., not lacking factor V), but this test is rarely used clinically and is of only historical interest.

- Fibrinogen and factors II, VII, VIII, X, XII and XIII are increased by 20-200%.

- Von Willebrand factor rises.

- Increased activity of fibrinolysis inhibitors, TAF1, PAI-1 and PAI-2. The level of PAI-1 also increases markedly.

- Levels of antithrombin III, protein C, factor V and factor IX most often remain unchanged or increase slightly.

The end result of these changes is an increase in the tendency to thrombosis, an increase in the likelihood of venous thrombosis during pregnancy and, especially, in the postpartum period. Along with contraction of the myometrium and an increase in the level of decidual tissue factor, hypercoagulability protects the pregnant woman from excessive bleeding during labor and delivery of the placenta.

APTT remains normal during pregnancy but may decrease slightly. Prothrombin time may be shortened. Bleeding time does not change.

The timing of normalization of blood clotting activity in the postpartum period may vary depending on factors, but everything should return to normal within 6-8 weeks after delivery. The hemostasiogram should not be assessed earlier than 3 months after delivery and after lactation is completed to exclude the influence of pregnancy factors.

The hemostasiogram should not be assessed earlier than 3 months after delivery and after lactation is completed to exclude the influence of pregnancy factors.

The influence of acquired or inherited thrombophilia factors on pregnancy is an area for research.

Postpartum period

Hematological changes associated with pregnancy return to normal 6-8 weeks after delivery. The rate and nature of the normalization of changes associated with pregnancy, specific hematological parameters are described above in the section on each parameter.

Hematological complications during pregnancy

- Iron deficiency anemia.

- Thrombocytopenia.

- Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia.

- Acquired hemophilia A.

- Venous thrombosis.

- Rh and non-Rh alloimmunization. For diagnosis, an analysis is carried out for Rh antibodies and anti-group antibodies.

- A manifestation of a previously unrecognized coagulation disorder, such as von Willebrand disease, most commonly manifests in women during pregnancy and childbirth.

For screening for von Willebrand disease, an assay is given to assess platelet aggregation with ristocetin.

For screening for von Willebrand disease, an assay is given to assess platelet aggregation with ristocetin. - Aplastic anemia.

Other articles in this section

-

ToRCH infections and pregnancy

What are ToRCH infections, what are the dangers of these infections during pregnancy, how and when is the examination performed, how to interpret the results. Perinatal infections account for approximately 2-3% of all congenital fetal anomalies.

-

Pregnancy Tests at CIR Laboratories

In our laboratory, you can undergo a complete examination in the event of pregnancy, take tests at any time, and in our clinics you can conclude an agreement on pregnancy management.

-

Pregnancy hCG calculator online

The hCG calculator is used to calculate the increase in hCG (the difference between two tests taken at different times).

The increase in hCG is important for assessing the development of pregnancy.

Normally, in the early stages of pregnancy, hCG increases by about 2 times every two days. As the hormone levels increase, the rate of increase decreases.

Normally, in the early stages of pregnancy, hCG increases by about 2 times every two days. As the hormone levels increase, the rate of increase decreases. -

False positive pregnancy test or why hCG is positive but not pregnant?

When can a pregnancy test be positive?

-

The norm of hCG during pregnancy. Table of hCG values by week. Elevated HCG. Low HCG. HCG in ectopic pregnancy. hCG during IVF (hCG after replanting, hCG at 14 dpo).

hCG or beta-hCG or total hCG - human chorionic gonadotropin - a hormone produced during pregnancy. HCG is formed by the placenta, which nourishes the fetus after fertilization and implantation (attachment to the wall of the uterus).

-

Risk assessment of pregnancy complications using prenatal screening

Prenatal screening data allow assessing not only the risks of congenital pathology, but also the risk of other pregnancy complications: intrauterine fetal death, late toxicosis, intrauterine hypoxia, etc.

-

Parvovirus B19 and parvovirus infection: what you need to know when planning and getting pregnant.

What is a parvovirus infection, how is the virus transmitted, who can get sick, what is the danger of the virus during pregnancy, what tests are taken for diagnosis.

-

Pregnancy planning

Obstetrics differs from other specialties in that during the physiological course of pregnancy and childbirth, in principle, it is not part of medicine (the science of treating diseases), but is part of hygiene (the science of maintaining health). Examination during pregnancy planning.

-

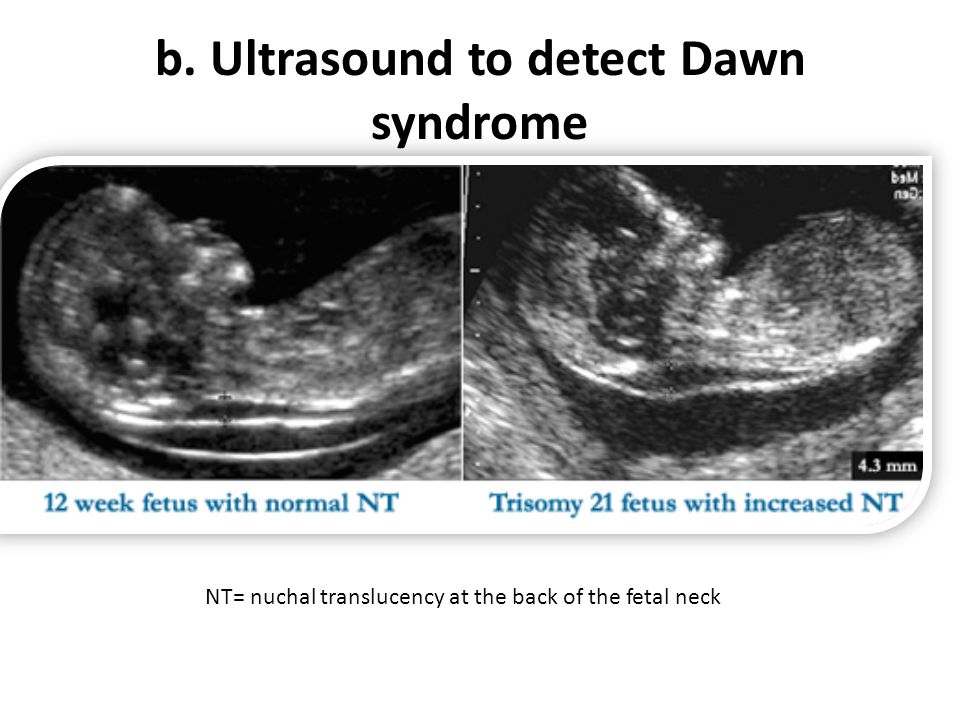

1st and 2nd trimester prenatal screening ("double", "triple" and "quadruple" tests)

Prenatal screening are tests conducted on pregnant women to identify risk groups for pregnancy complications.

-

Testosterone during pregnancy. Androgens: their formation and metabolism during normal pregnancy.

Hyperandrogenism during pregnancy. "Male" hormones during pregnancy.

Hyperandrogenism during pregnancy. "Male" hormones during pregnancy. During pregnancy, the level of testosterone and other androgens changes. The change in these levels depends, among other things, on the sex of the fetus.

All articles of the section

Reticulocytes (blood level determination)

SKU: 00310

Cost of analysis

in the online store: 7% discount!

Plain

456rubExpress

911 rublesLab:

Regular

490rub

Express

980 rubles

the cost is indicated without taking into account the cost of sampling biological material

Add to Basket

Analysis results ready

Regular*: same day (subject to return before 12.00)

Analysis submission date:

Completion date:

*excluding the day of delivery, see rules.

Express

Where and when you can rent

- Buninskaya alley

- Voykovskaya

- Dubrovka

- Maryino

- Novokuznetskaya

- Podolsk

- Weekdays: from 7.45 to 12.00

- Weekends: from 8.45 to 12.00

Changes in work schedule

Preparation for analysis

General recommendations for testing

On an empty stomach, at least 8 hours after the last meal.

Biomaterial sampling

- Blood sampling for laboratory tests

Methods and tests

Microscopy with special stains. Quantitative, ‰

Files

Download a sample of the analysis result

Reticulocytes are the immediate precursors of mature erythrocytes; the indicator reflects the production of erythrocytes in the red bone marrow (assessment of erythropoiesis). The study of the number of reticulocytes is carried out in conditions that are accompanied by blood loss, anemia, after treatment with cytotoxic drugs, bone marrow transplantation.