Prostaglandins for labor

Introduction - Which method is best for the induction of labour? A systematic review, network meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis

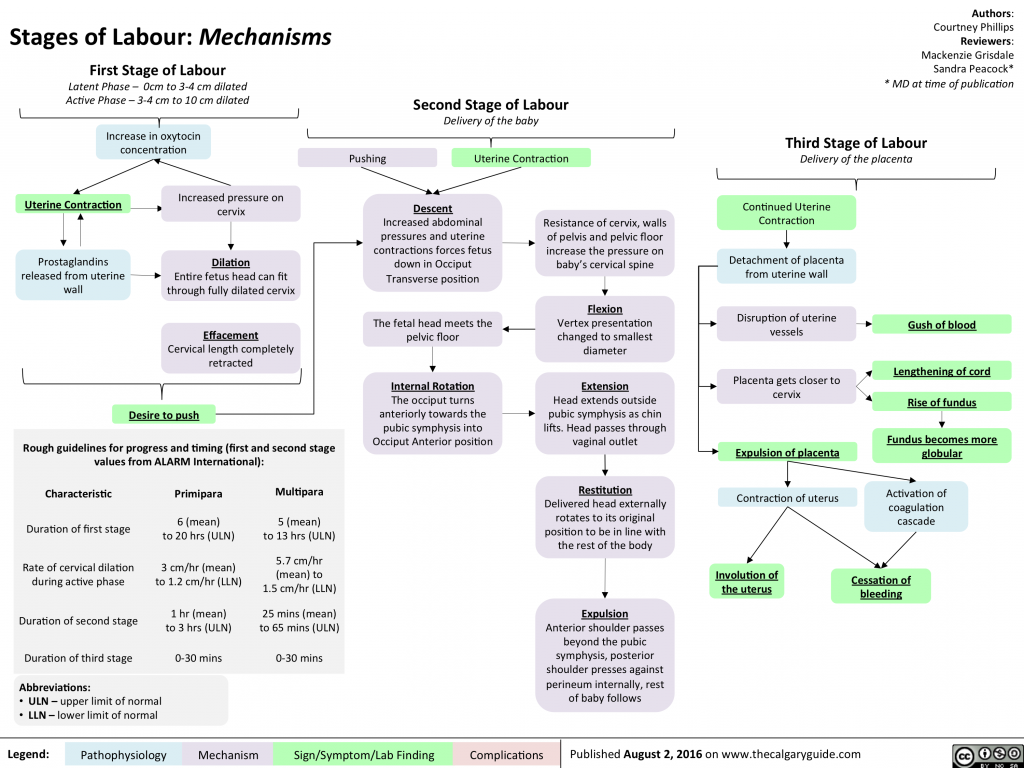

Description of the health problem

There were 698,512 live births in England and Wales in 2013.1 More than one in five births followed labour induction; this represents > 150,000 pregnant women in England2 and Wales3 per year. There is evidence that the number of labour inductions has been steadily increasing over the past two decades. NHS England maternity statistics for 2010 noted that 21.3% of births followed induction of labour, and by 2012–13 this figure had increased to 23.3%.4

Induction of labour is carried out for a number of clinical indications.5,6 The most common reasons include post-term pregnancy (defined as 41+0 weeks’ gestation), prelabour rupture of the amniotic membranes (PROM) or when the well-being of the woman or baby may be compromised by prolonging the pregnancy (e. g. in cases of fetal growth restriction or pre-eclampsia).

There is a broad range of methods available for induction of labour. The choice of method may depend on national guidelines and local protocol, as well as individual clinical factors. The advantages and disadvantages of different methods vary, and the choice of method has implications for women and the UK NHS.

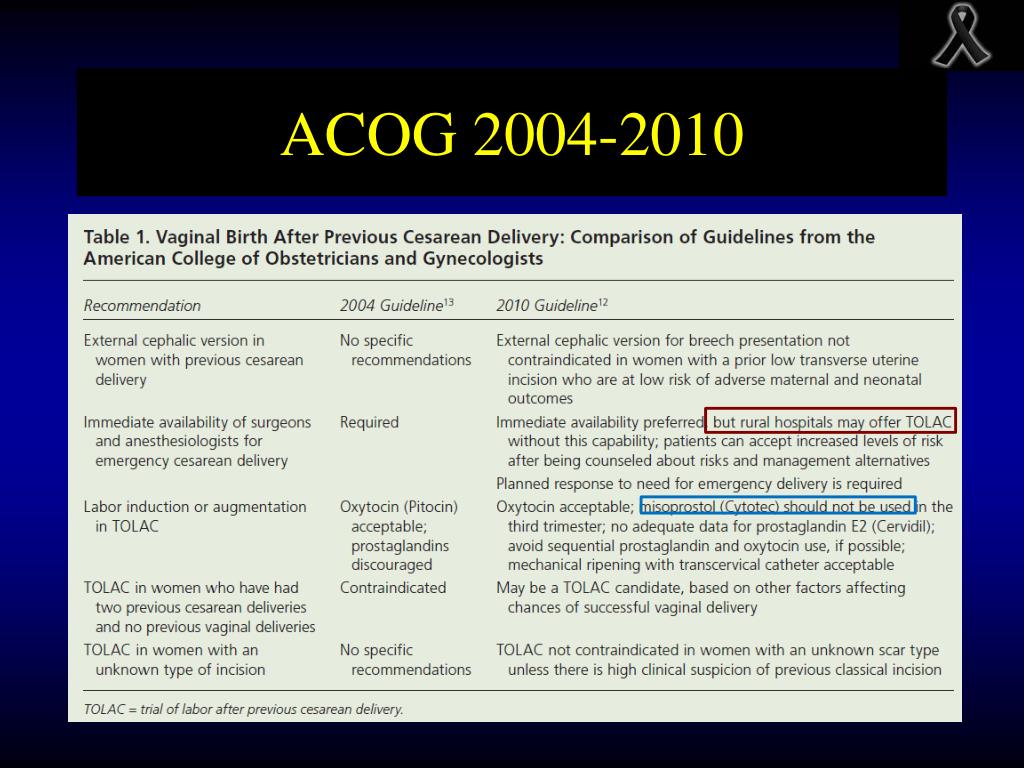

From a clinical perspective, the decision about which method to use for induction of labour can be influenced by the woman’s readiness for labour, for example whether or not membranes have ruptured spontaneously or whether or not the cervix remains undilated at the start of the induction process. Different methods used for inducing labour have different mechanisms of action, and vary in terms of how quickly birth is achieved and the likelihood of causing complications in women with different clinical characteristics. Thus, the choice of method will take into account the reason for induction and its urgency. The woman’s obstetric and medical history is also considered. For example, there is evidence that women may be more sensitive to drugs that stimulate the uterus if they have had a previous birth, and women who have a scar from a previous caesarean birth are at increased risk of uterine rupture, which can result in hysterectomy and fetal death.7

For example, there is evidence that women may be more sensitive to drugs that stimulate the uterus if they have had a previous birth, and women who have a scar from a previous caesarean birth are at increased risk of uterine rupture, which can result in hysterectomy and fetal death.7

Different methods also have different direct costs, and some methods require continuous monitoring of the woman throughout labour. Consequently, the choice of induction method may have significant implications for NHS resources, especially if the method is known to increase the risk of complications requiring a caesarean section (CS).

Women may wish to experience a natural onset of labour, and there is evidence that an induced labour can have a negative impact on their overall experience of childbirth.8 Some methods of induction are painful or unpleasant, and some are associated with distressing side effects, such as headache or nausea. Women may also have preferences about which method is used and may prefer non-pharmacological approaches. On the other hand, women will want their baby to be born safely, and timely induction may improve outcomes for women and babies.5 Women facing decisions about induction of labour require up-to-date information about the range of options available, including alternative and complementary methods.

On the other hand, women will want their baby to be born safely, and timely induction may improve outcomes for women and babies.5 Women facing decisions about induction of labour require up-to-date information about the range of options available, including alternative and complementary methods.

Description of available interventions and current service provision/policy

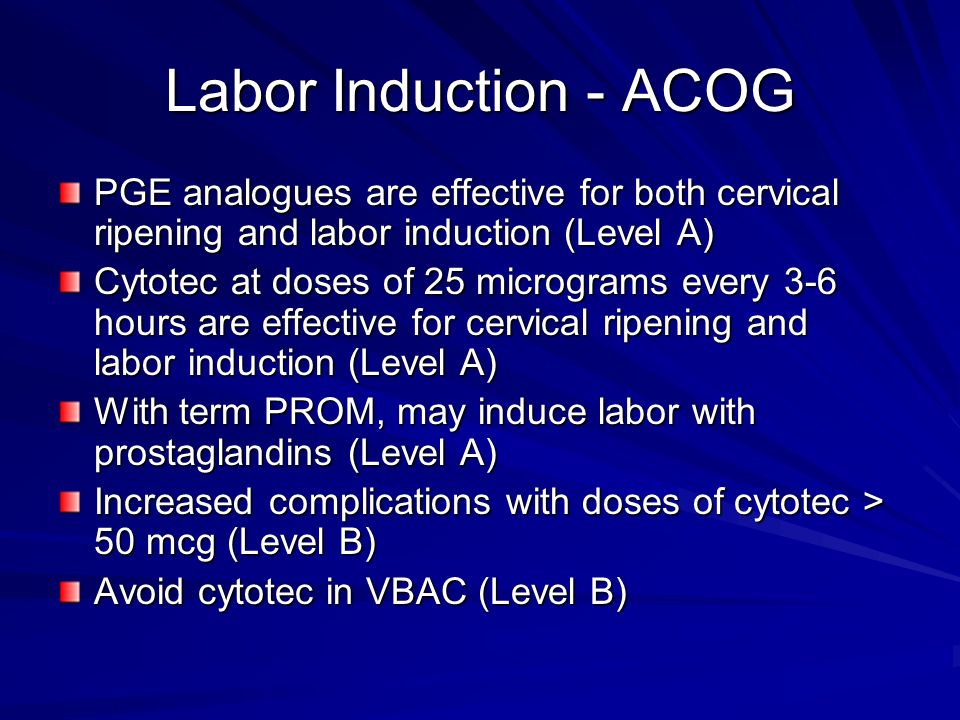

In the NHS context, choice of induction method is typically between prostaglandins and oxytocin combined with artificial rupture of membranes. UK clinical guidelines published in 20089 identified vaginal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) as ‘the preferred method of induction’. We note that this recommendation was not based on a quantitative overview of the evidence of the effects and safety of all available methods, or from the synthesis and analysis of data from a range of comparisons. Furthermore, this guideline9 did not recommend any particular type (gel, tablet or pessary) or dose of PGE2 because trial evidence has rarely compared different PGE2 preparations. Potential updating of the current guidance is awaiting the publication of this report.10

Potential updating of the current guidance is awaiting the publication of this report.10

Despite its importance, the question of resource use for the NHS has been relatively under-studied, and uncertainty remains about the costs that are associated with induction of labour. There is evidence that inducing labour in women with complications is associated with lower health-service costs than costs associated with expectant management.11–13 However, there is little evidence on the costs associated with specific methods of induction compared with others. Randomised trials in which one method of induction has been compared with another have only rarely included economic analyses.14

A broad range of pharmacological, mechanical, complementary and alternative methods have been used to induce labour. In the remaining sections of this chapter, we describe all of the pharmacological and mechanical methods for third-trimester induction of labour or cervical ripening which have been used in clinical practice and that have been examined in randomised trials. Complementary or alternative methods have been less commonly used in NHS settings but have been used in comparable settings in other countries. Complementary and alternative methods are included here, as information on the effects and safety of such methods may be important for women who prefer a less medicalised birth.

Complementary or alternative methods have been less commonly used in NHS settings but have been used in comparable settings in other countries. Complementary and alternative methods are included here, as information on the effects and safety of such methods may be important for women who prefer a less medicalised birth.

Pharmacological methods for the induction of labour

Prostaglandins: prostaglandin E

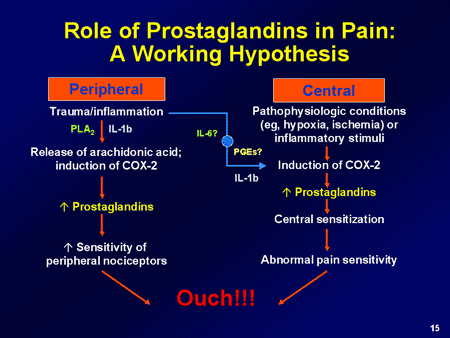

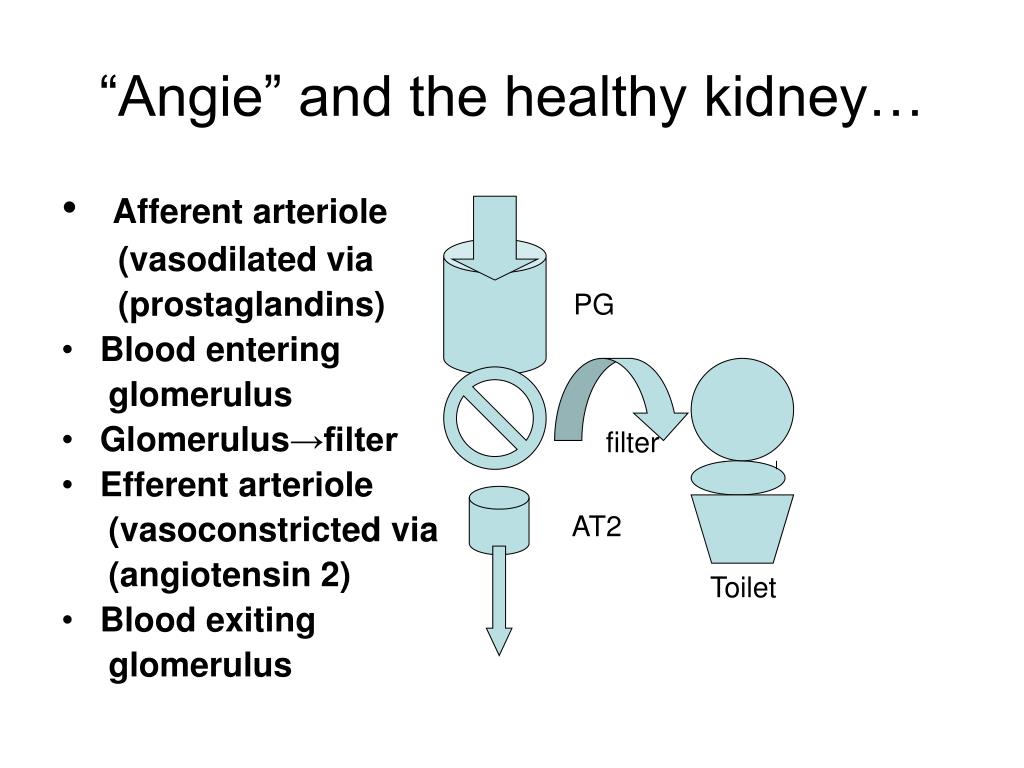

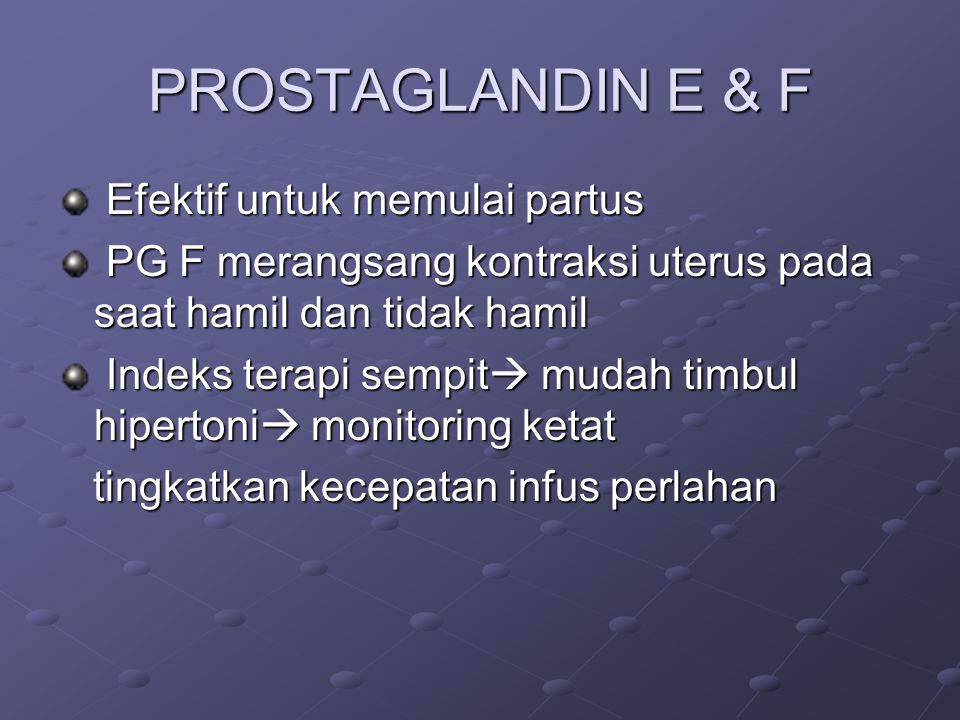

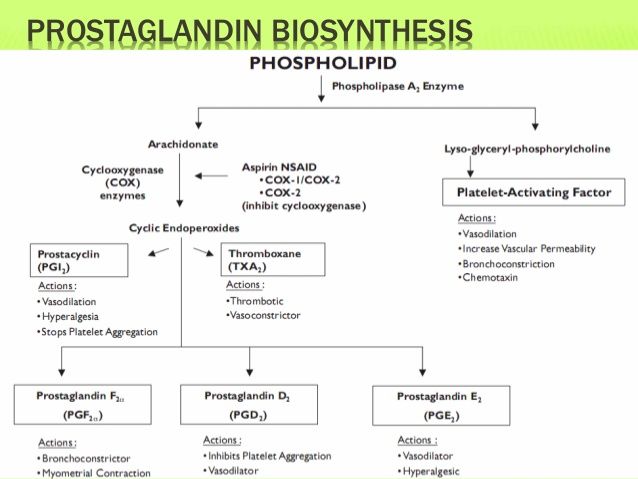

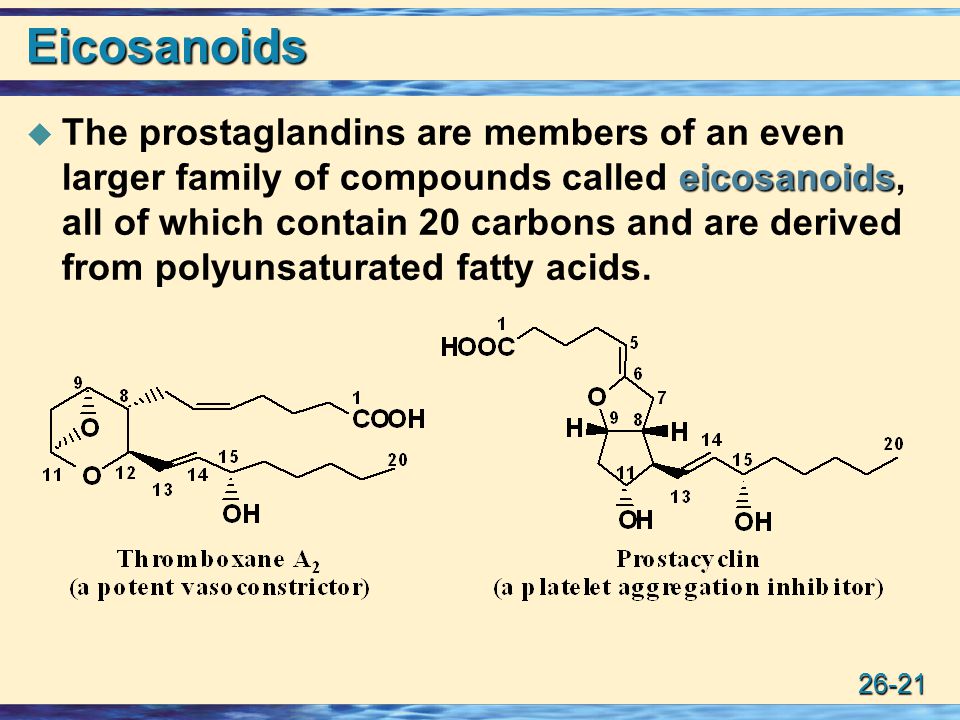

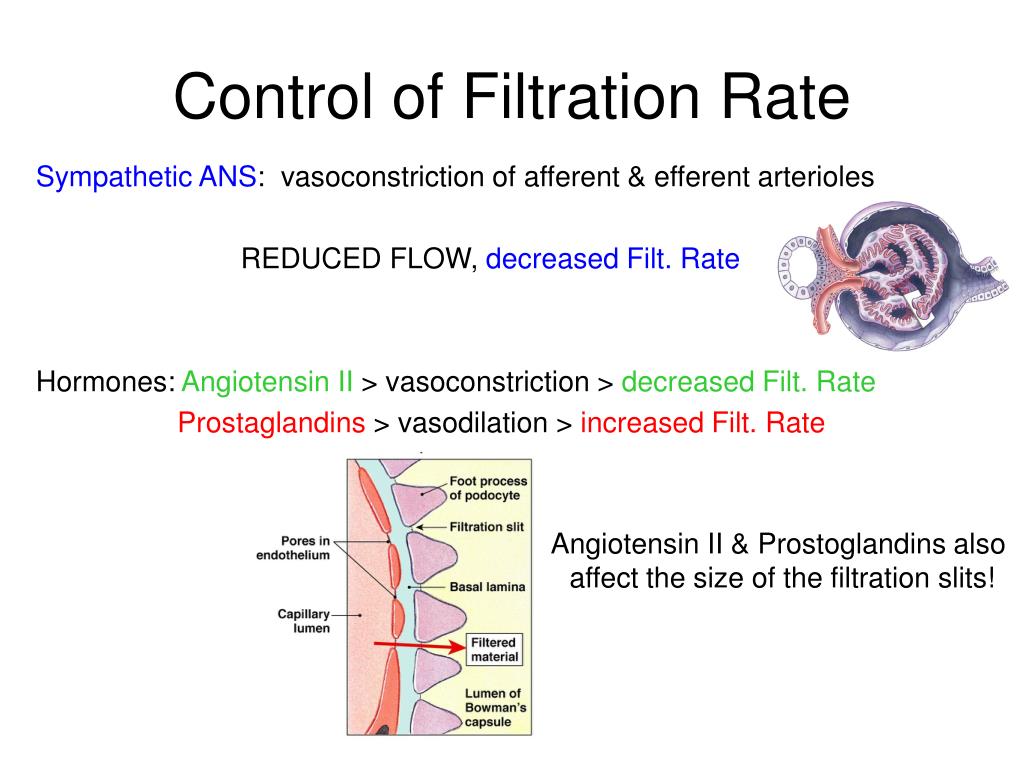

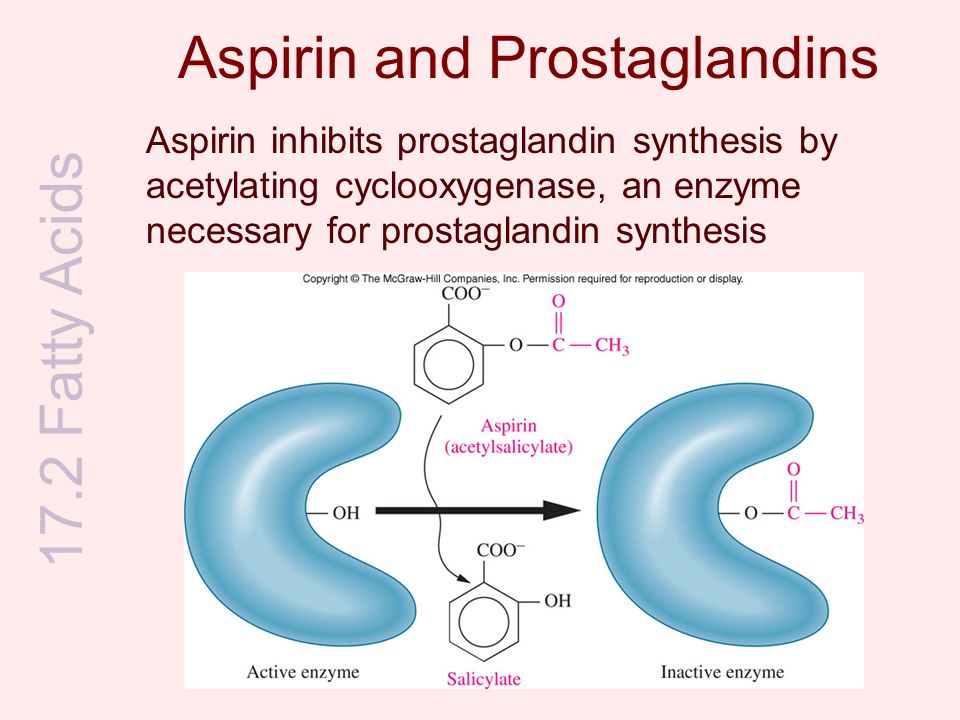

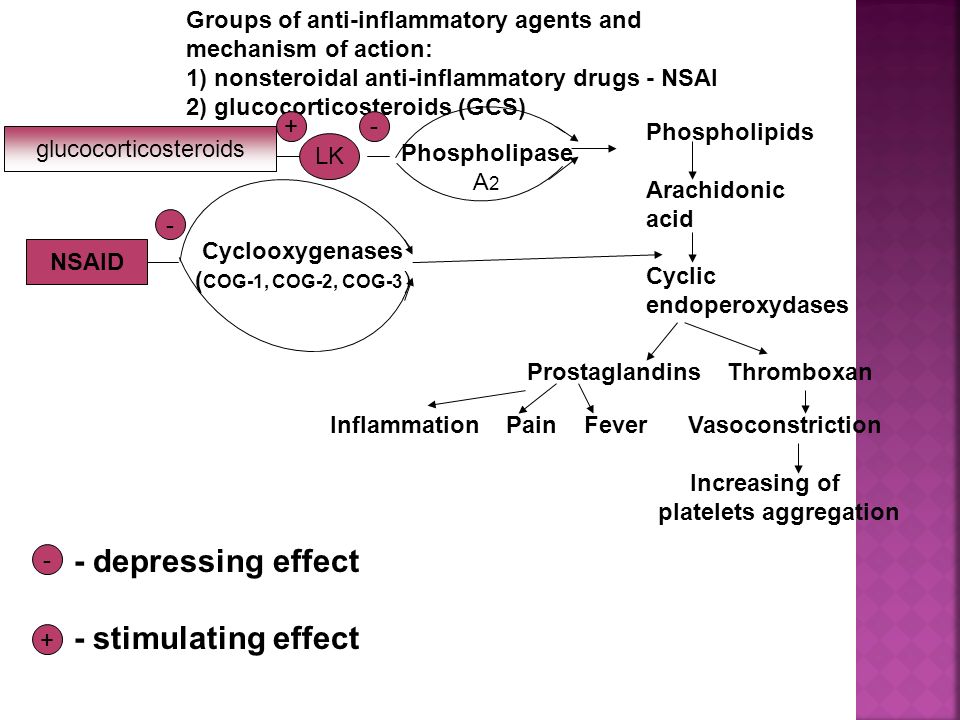

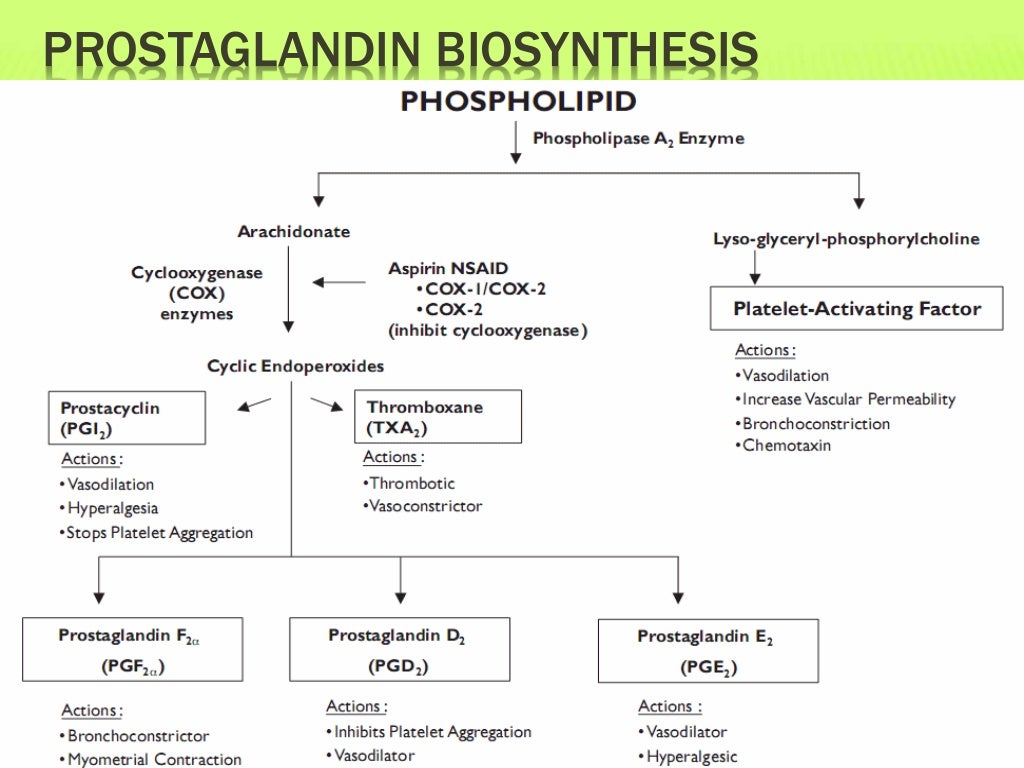

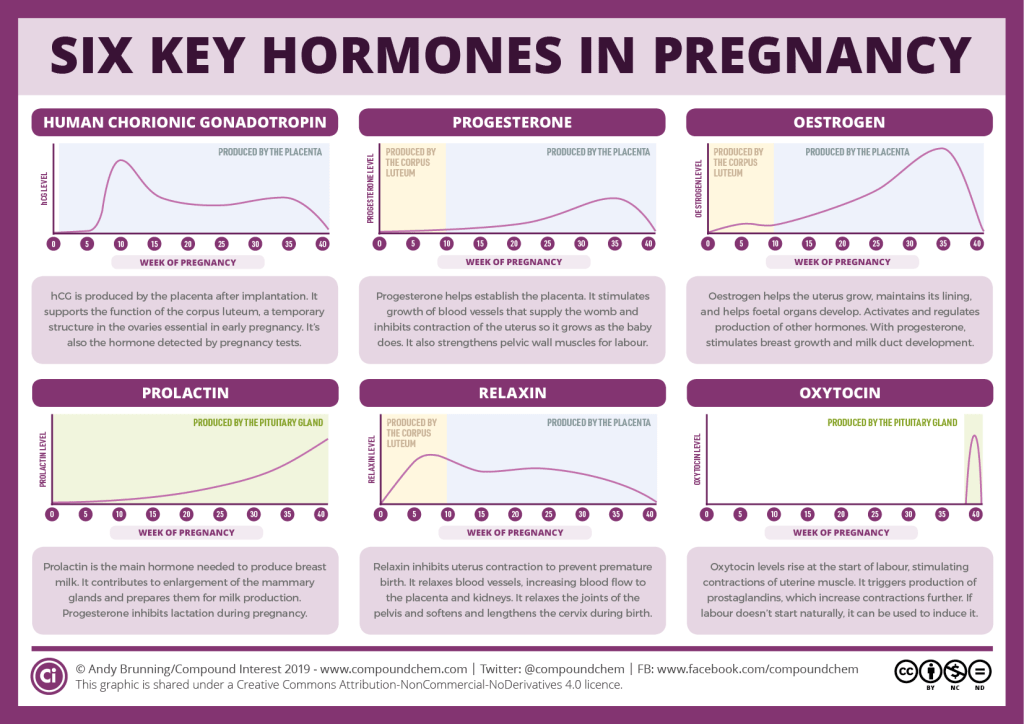

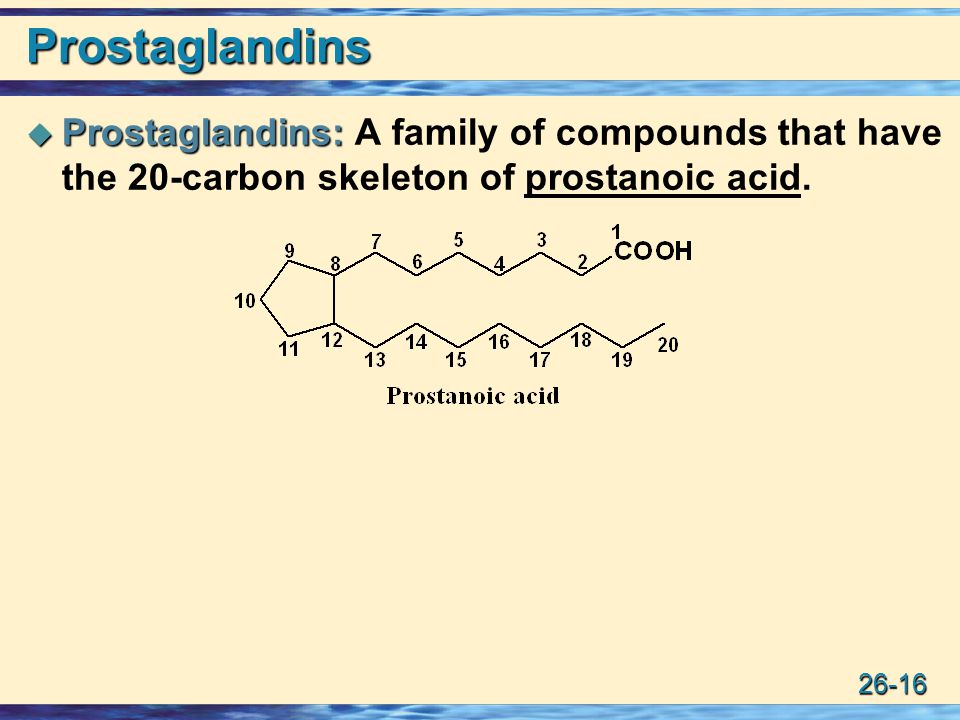

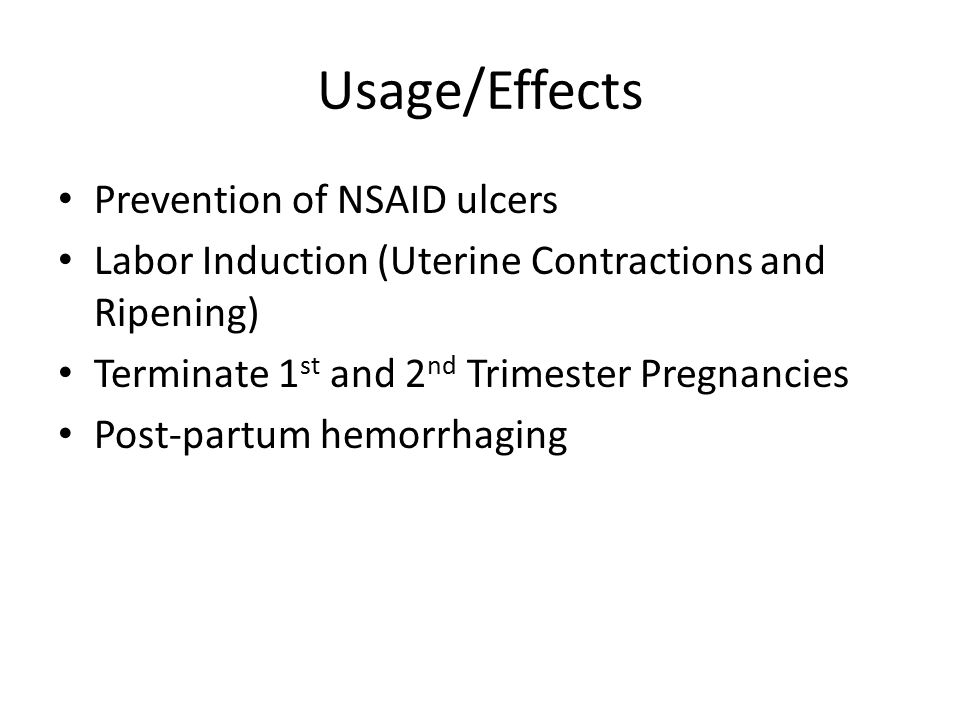

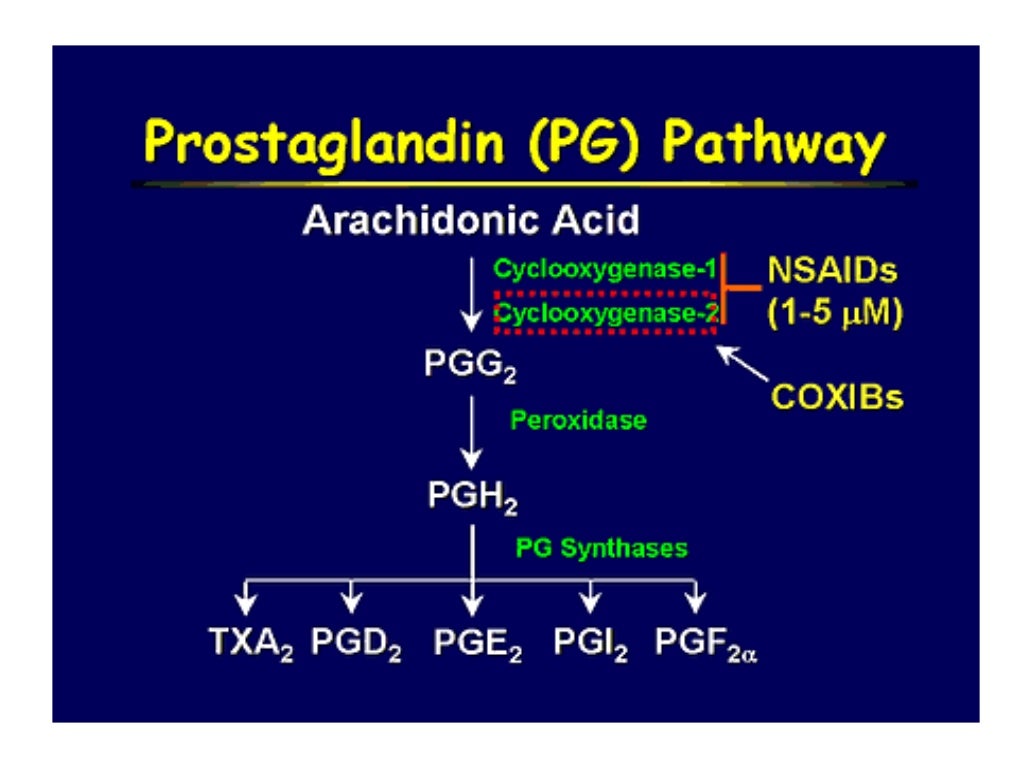

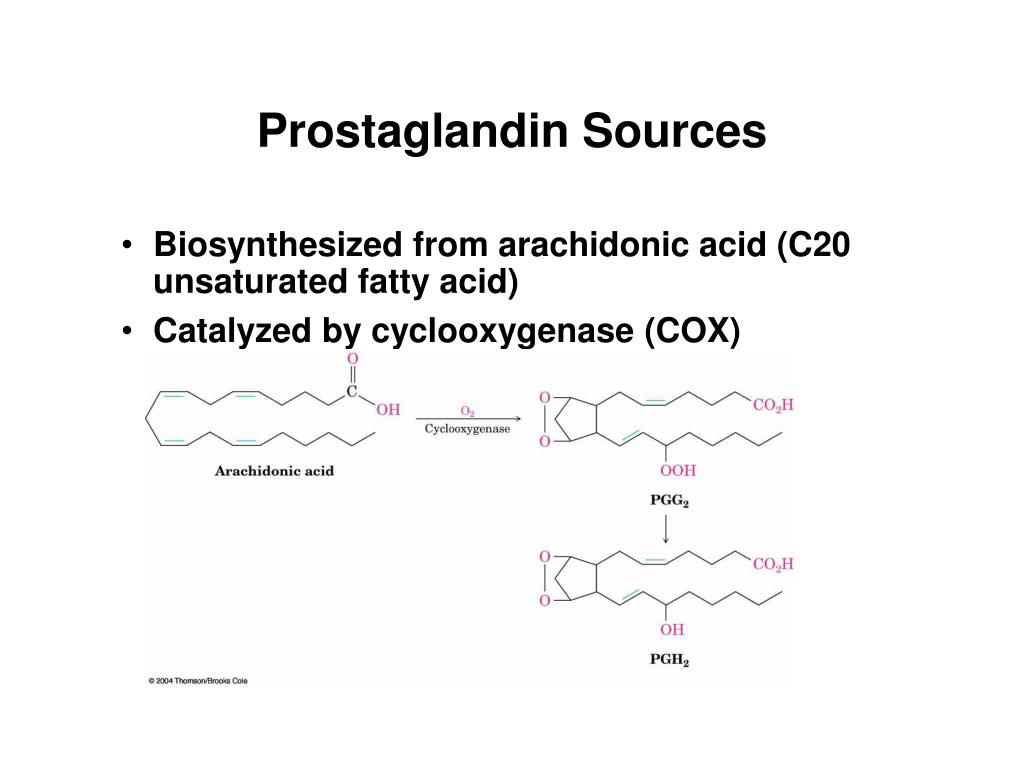

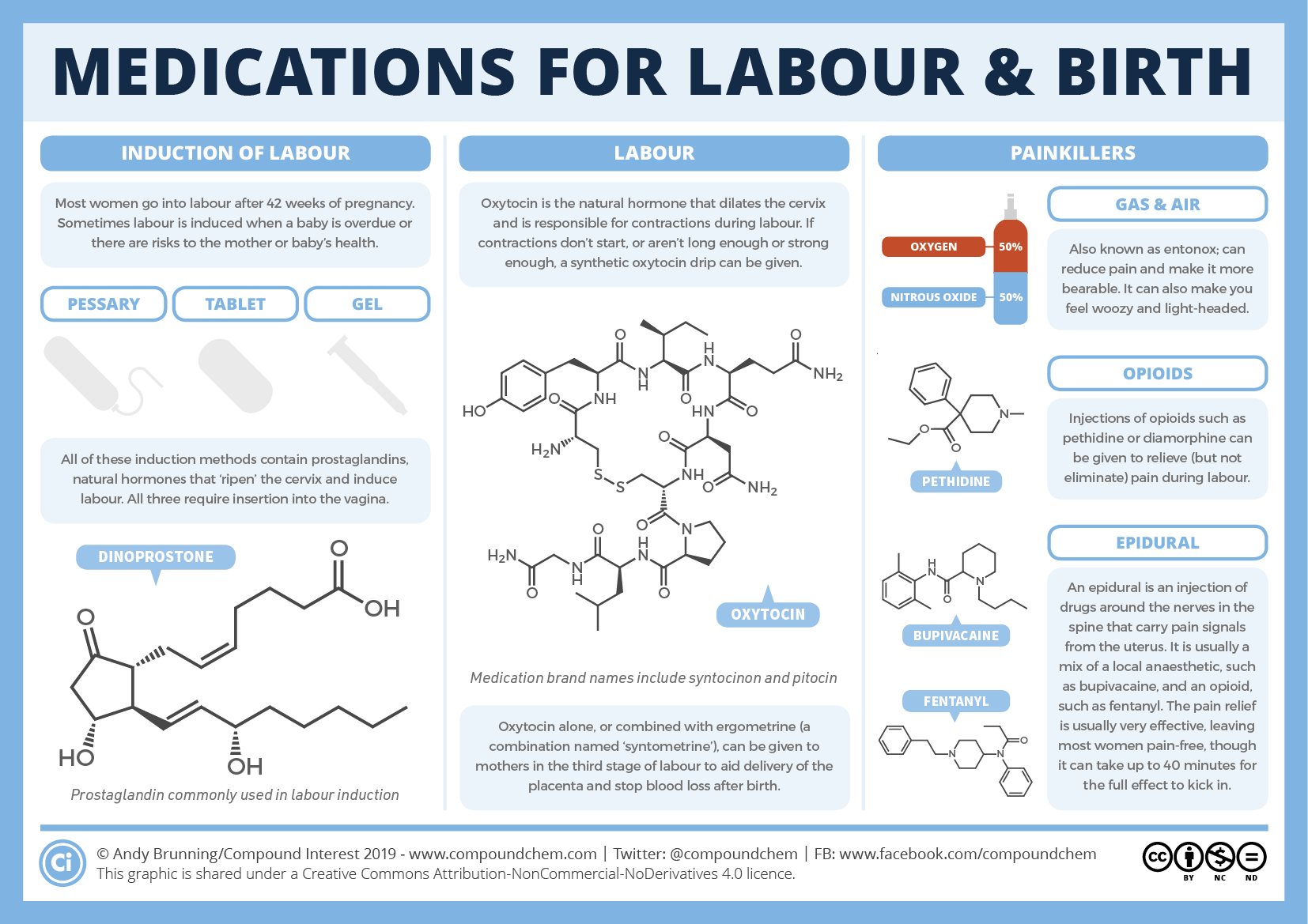

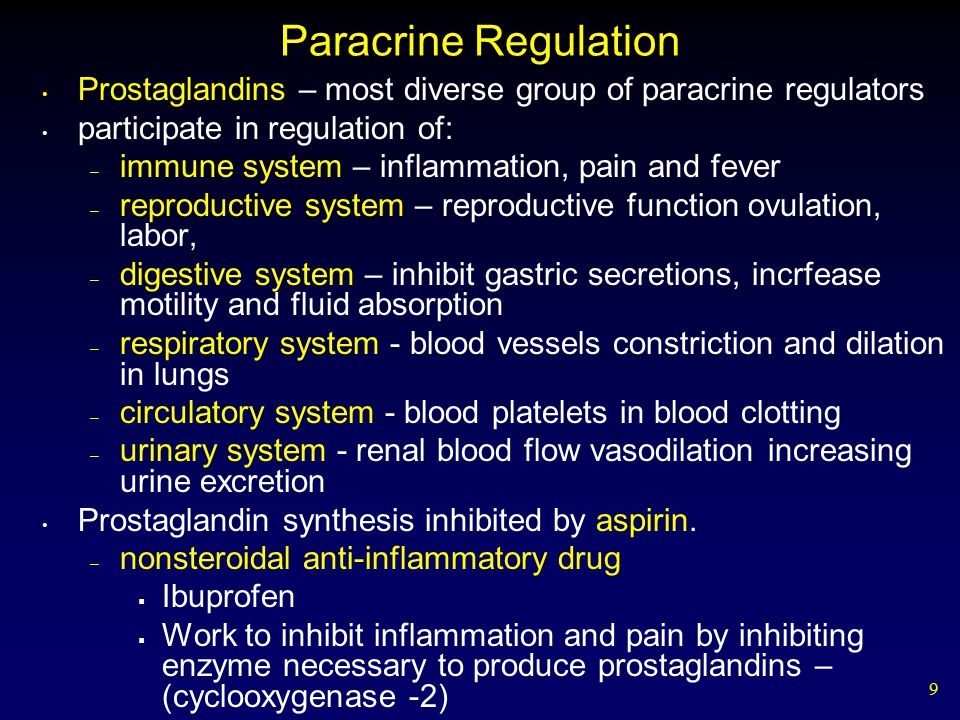

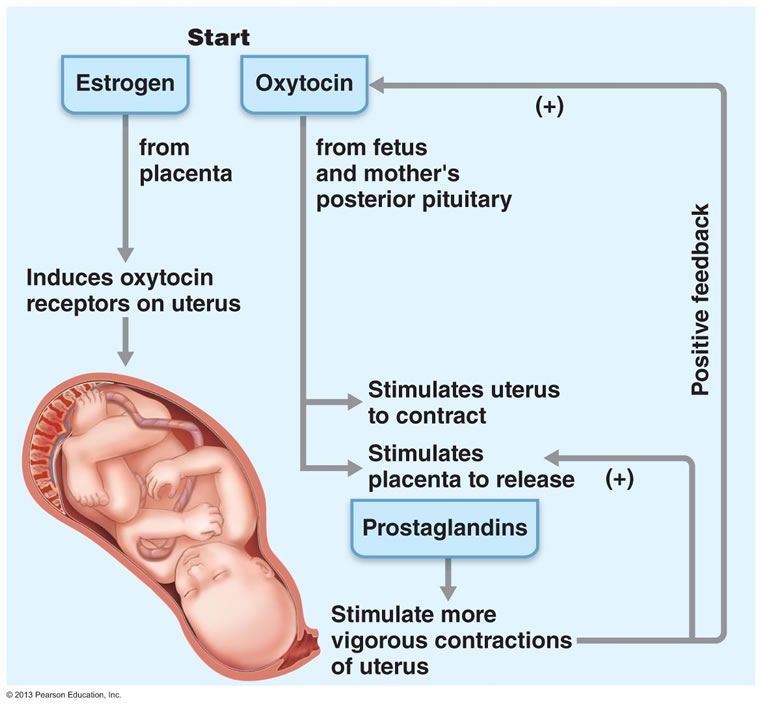

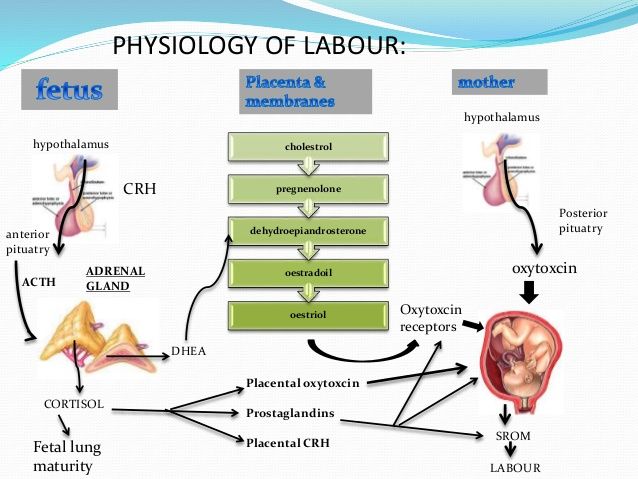

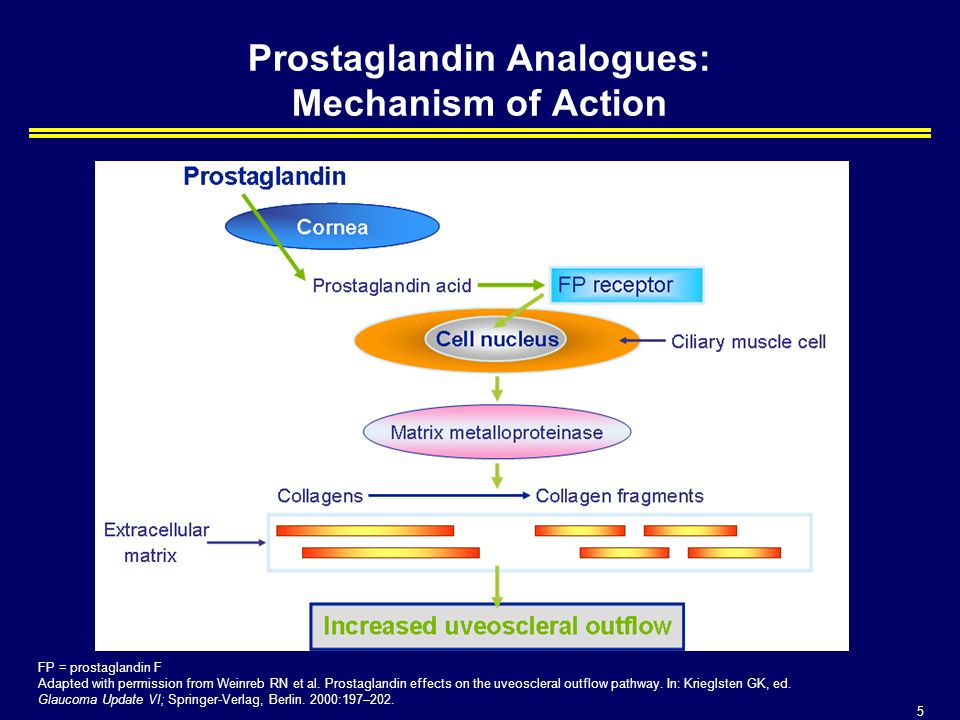

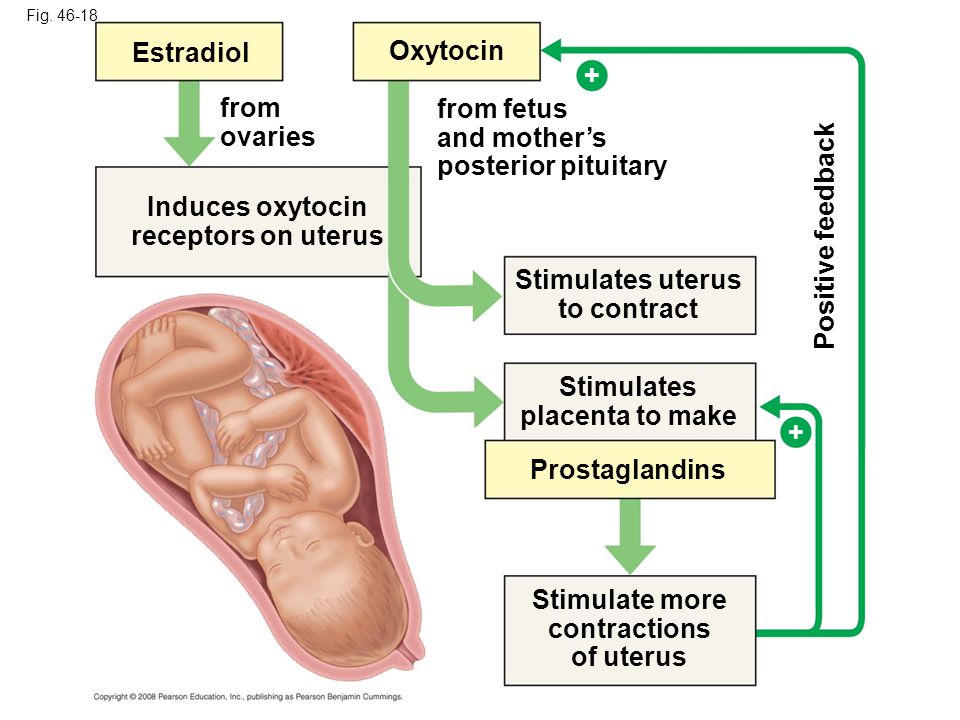

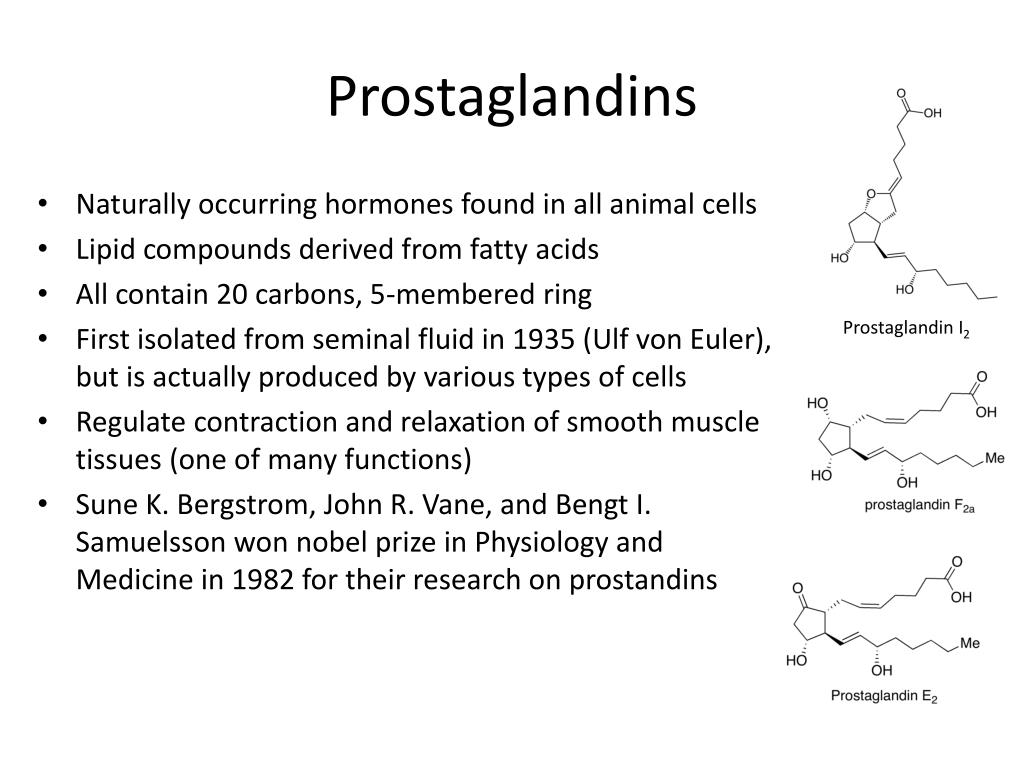

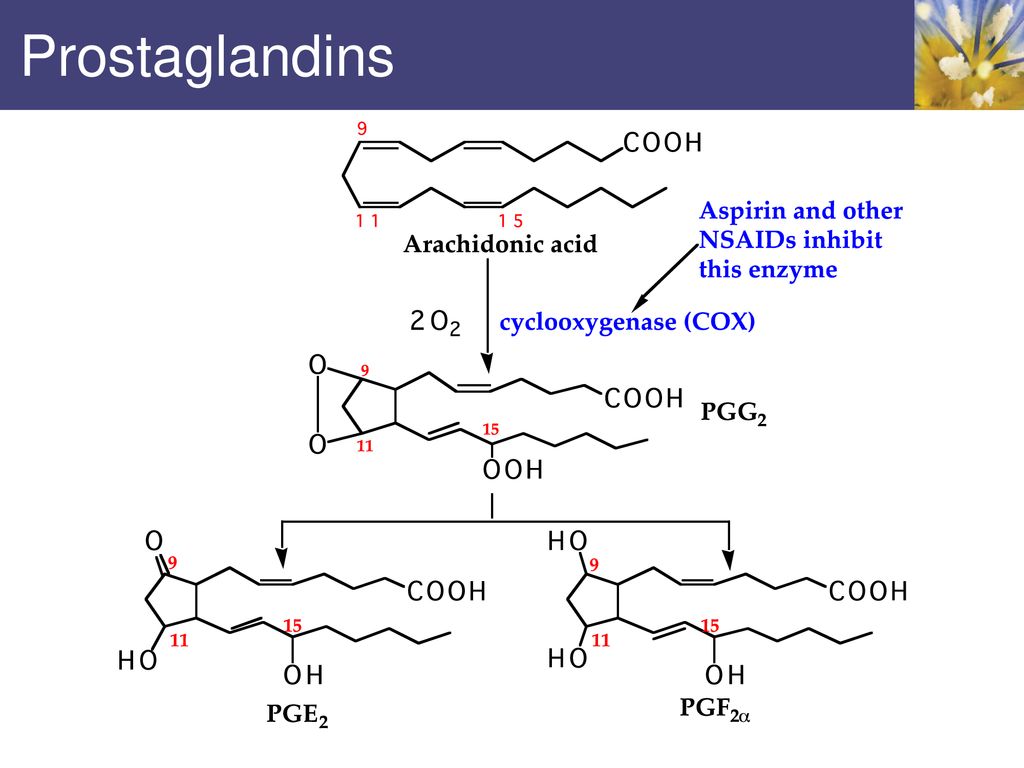

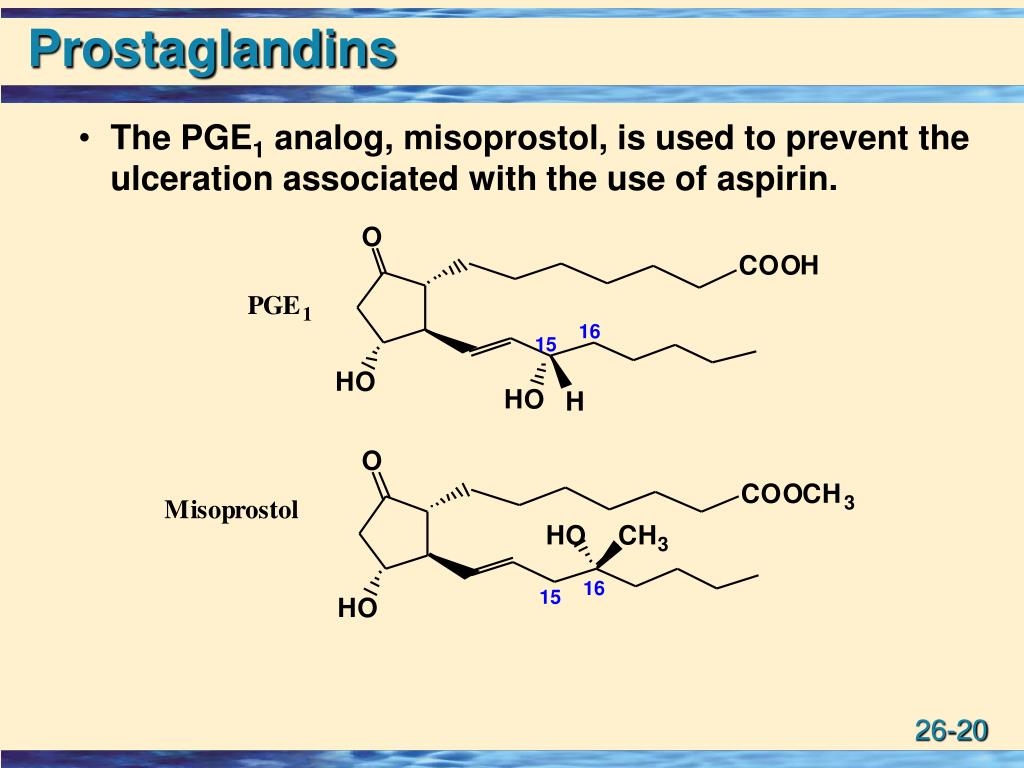

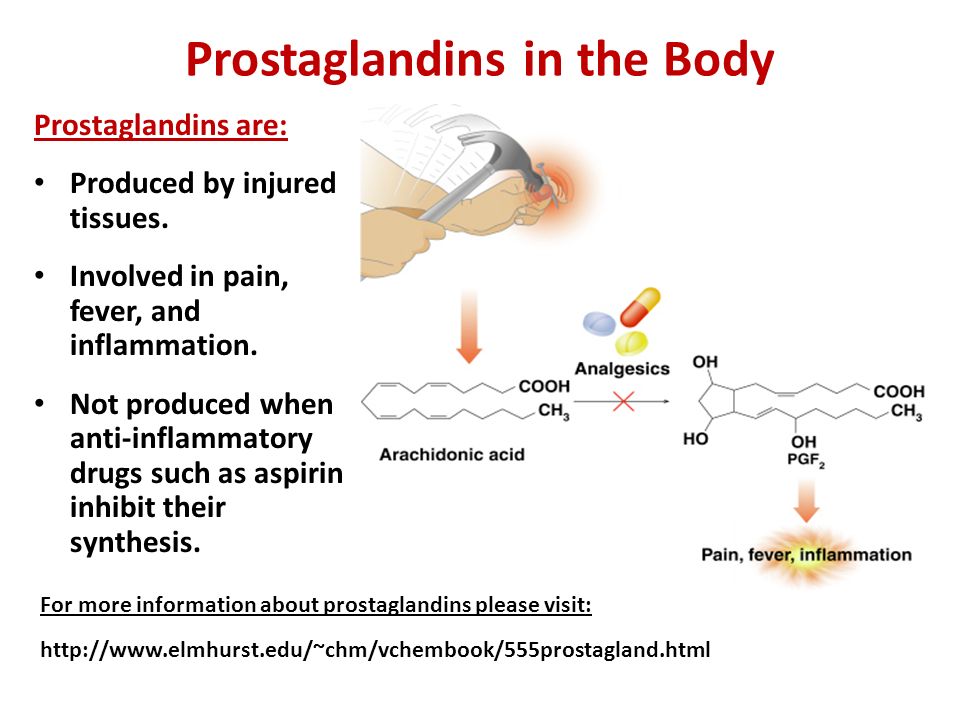

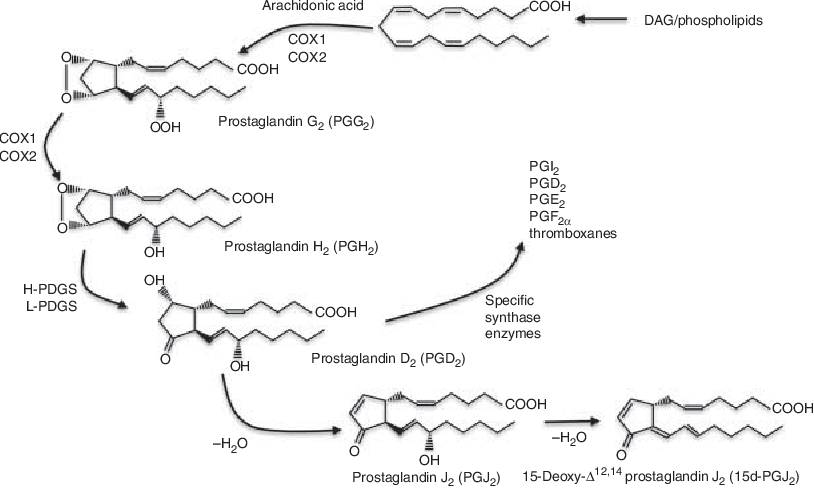

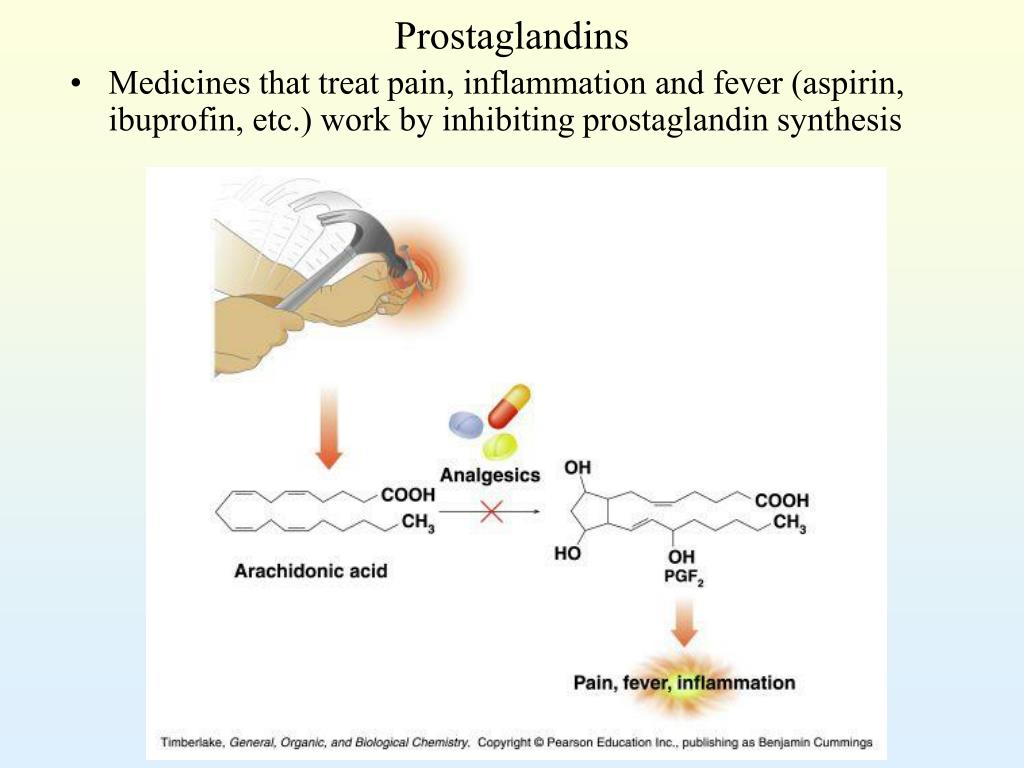

2 and prostaglandin F2 alphaProstaglandins are hormones produced naturally by the body that are important in the onset of labour. Synthetically manufactured prostaglandins have been used in clinical practice since the 1960s to ripen the cervix and induce uterine contractions. They are more frequently used in women when the cervix is unripe (i.e. with a Bishop score < 6). Prostaglandins promote cervical ripening and encourage the onset of labour by acting on cervical collagen so as to encourage the cervix to soften and stretch in preparation for childbirth. Prostaglandins may also stimulate uterine contractions.

Prostaglandins may also stimulate uterine contractions.

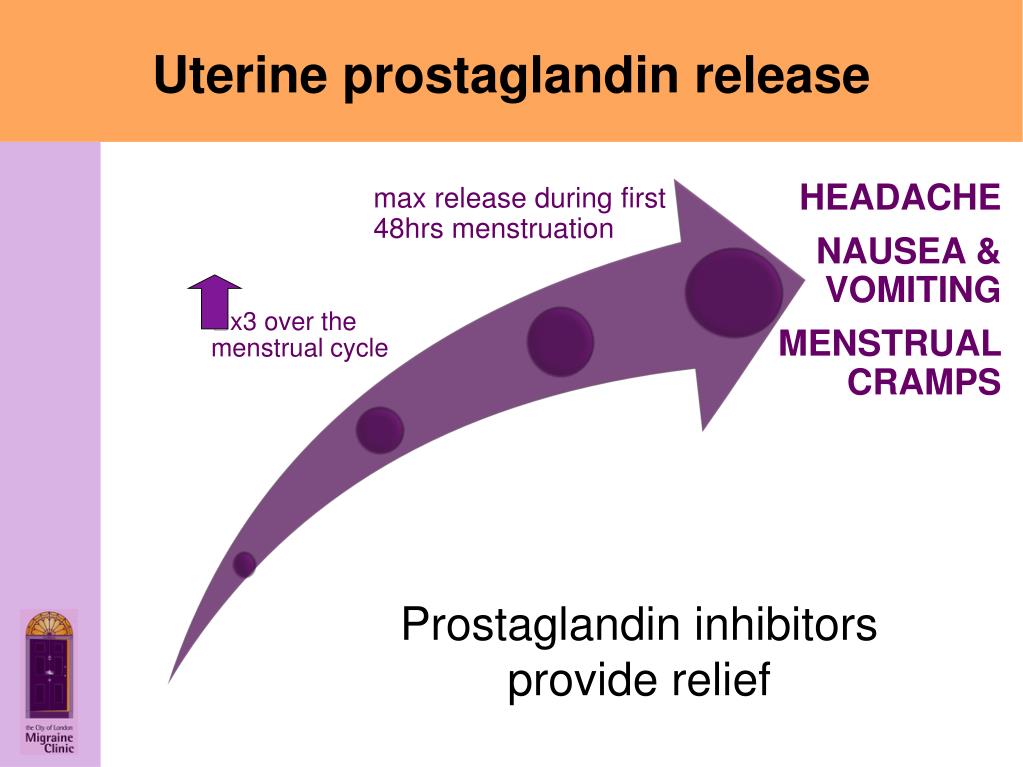

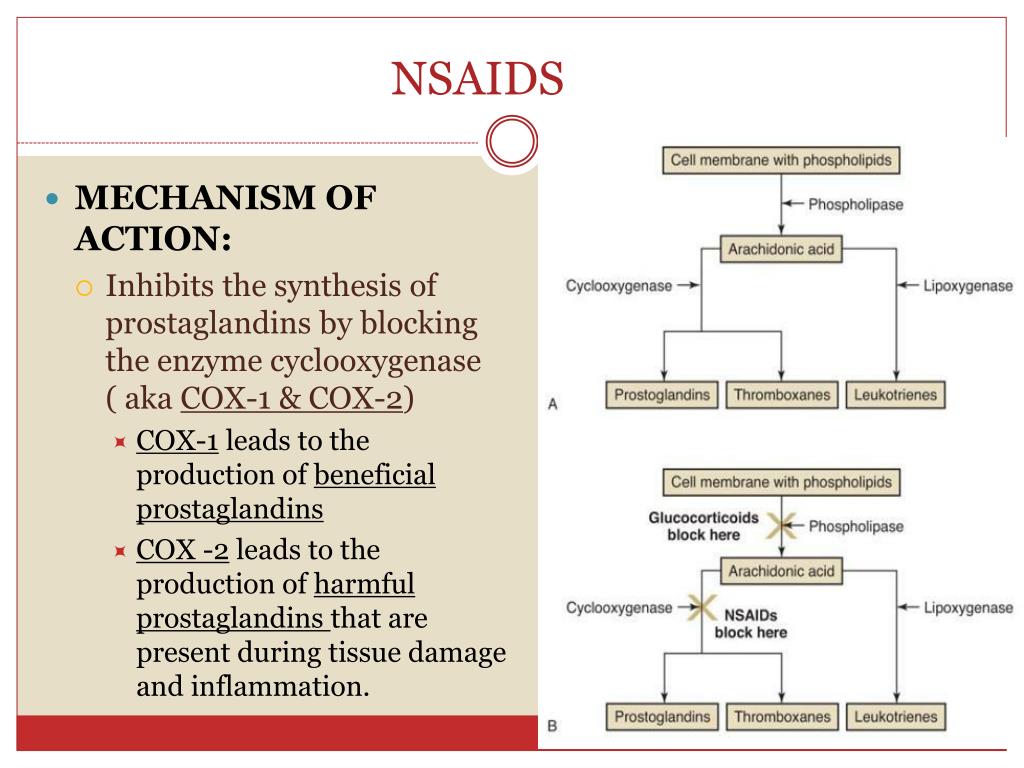

Despite the widespread use of prostaglandins as part of labour induction, they can cause a number of side effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and fever. In addition, because of their effect on the uterus, prostaglandins can cause contractions that last too long, or are too frequent or are too strong. Excessive uterine activity, or hyperstimulation, may be associated with fetal distress, and in a small number of cases can lead to uterine rupture, especially in those women who have uterine scarring from surgery or a previous caesarean birth.

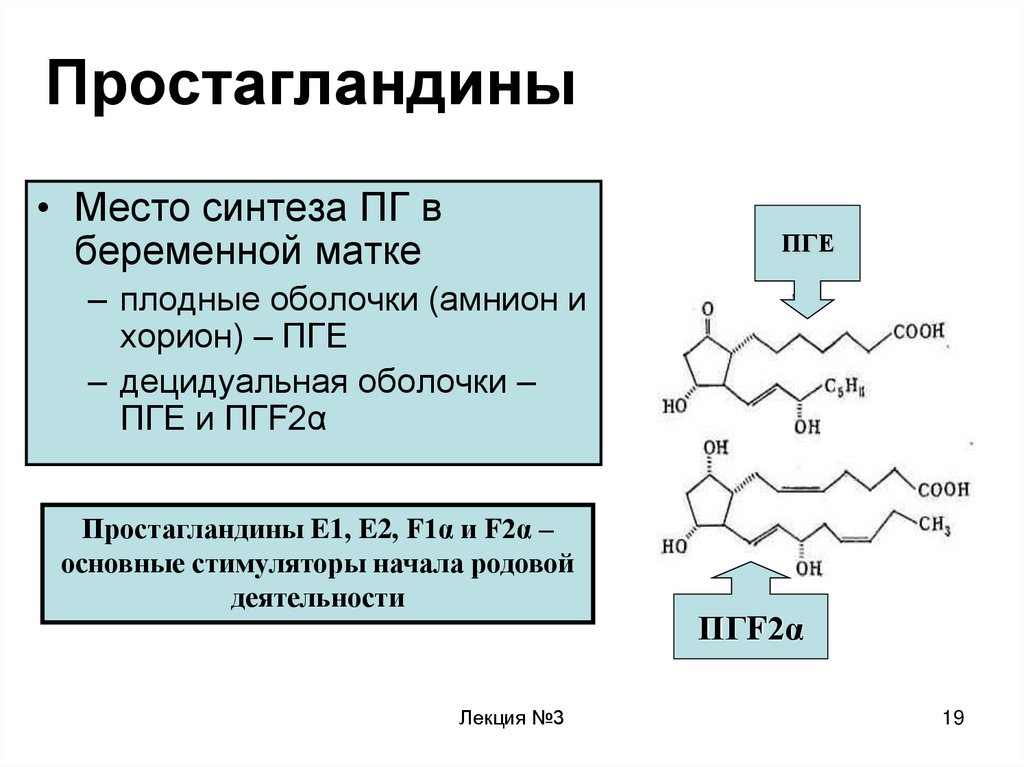

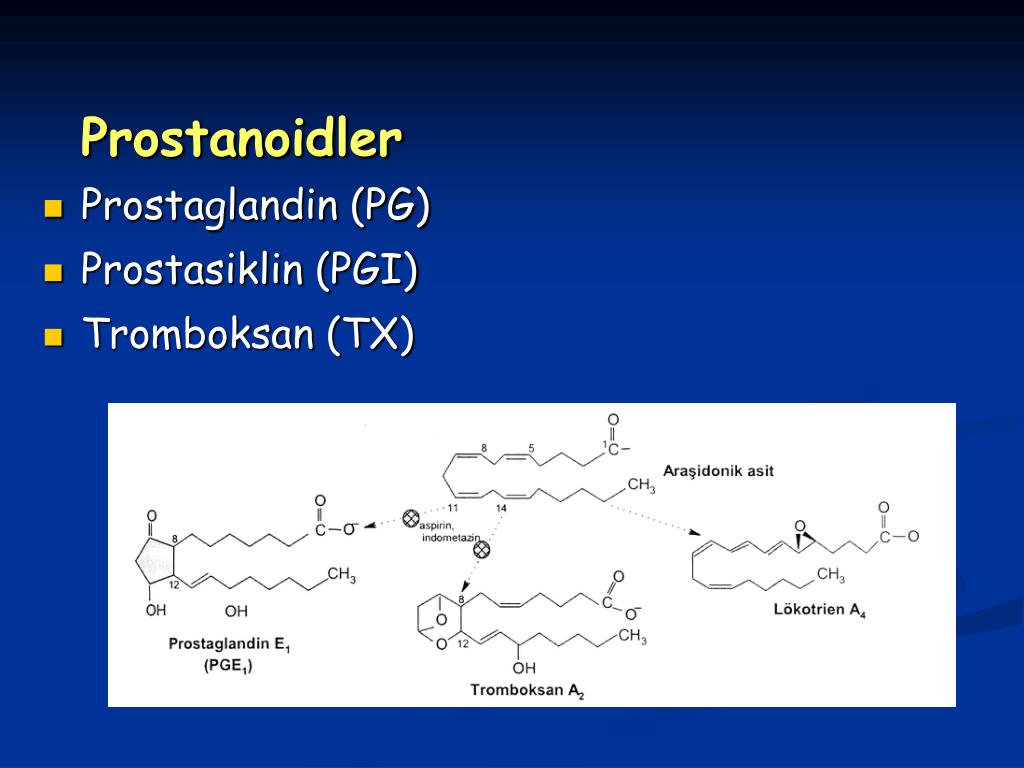

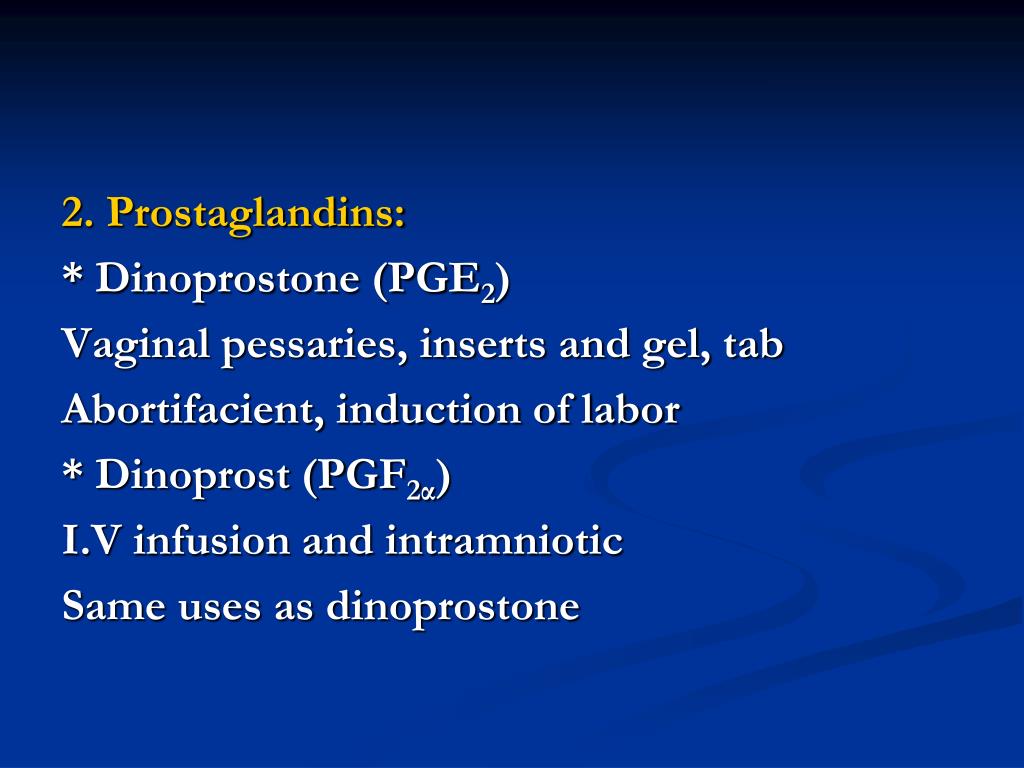

A large number of prostaglandin preparations have been available for labour induction, including prostaglandin F2 alpha (PGF2α, dinoprost), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostaglandin E (PGE1) and misoprostol (a synthetic analogue of PGE1, which is described separately: see Misoprostol). In the past, PGF2α was frequently used in clinical practice but, more recently, PGE2 (dinoprostone) has become the most commonly used formulation. Commercially produced PGE2 analogues are expensive and require refrigeration. These factors have limited use in low-resource settings.

Commercially produced PGE2 analogues are expensive and require refrigeration. These factors have limited use in low-resource settings.

Prostaglandins are available in a variety of formulations and doses, and may be given via various routes of administration, including vaginally, intracervically, orally and, less frequently, intravenously.

Vaginal and intracervical administration

Prostaglandin preparations for vaginal and intracervical administration include gels, lactose-based vaginal tablets, suppositories, pessaries or inserts.15,16 Dosages of prostaglandins (mainly PGE2) vary, depending on route and local protocol (frequently 0.5 mg for intracervical use, 2–3 mg for intravaginal use and 10 mg for sustained-release pessaries). There is also variation in terms of the number of applications and time intervals between repeated doses. Sustained-release vaginal pessaries have been developed to reduce the number of applications and vaginal examinations that are needed during induction of labour. Vaginal and intracervical administration are the most common forms of administration in current practice.

Vaginal and intracervical administration are the most common forms of administration in current practice.

In the meta-analysis we have treated different types of vaginal and intracervical PGE2 as different interventions as different preparations may vary in terms of rate of absorption, safety and cost. We have therefore included as separate interventions:

PGE2 vaginal tablets (lactose based).

PGE2 vaginal pessaries normal release (also sometimes referred to as suppositories), manufactured using various base materials, including wax and glycerine. [Note that this intervention includes a heterogeneous group of vaginal PGE2 preparations of varying composition. The base material used was not always clear, and pessaries were frequently produced in local pharmacies (i.e. not commercially available). We included this group of interventions in the network meta-analysis (NMA) and the cost analysis for completeness, even though they are not generally reproducible or available in the UK NHS.

]

]PGE2 vaginal pessaries sustained release (10- to 12-mg pessaries, single application).

PGE2 gel introduced via vaginal applicator.

PGE2 for intracervical administration.

Extra-amniotic administration

The administration of extra-amniotic prostaglandin gel was first carried out in the early 1970s. The gel is administered via a Foley catheter inserted through the cervix into the extra-amniotic space. The catheter is frequently left in place with the balloon inflated, and light traction may also be applied by taping the catheter to the woman’s leg. Extra-amniotic administration is no longer common in current practice.17

Intravenous administration

Intravenous (i.v.) prostaglandins are associated with increased rates of maternal vomiting and diarrhoea and are rarely used in current practice.18

Oral administration

Oral PGE2 and PGF2α have been available since the early 1970s. Oral administration is associated with gastrointestinal side effects and is seldom used nowadays.19

Oral administration is associated with gastrointestinal side effects and is seldom used nowadays.19

Misoprostol

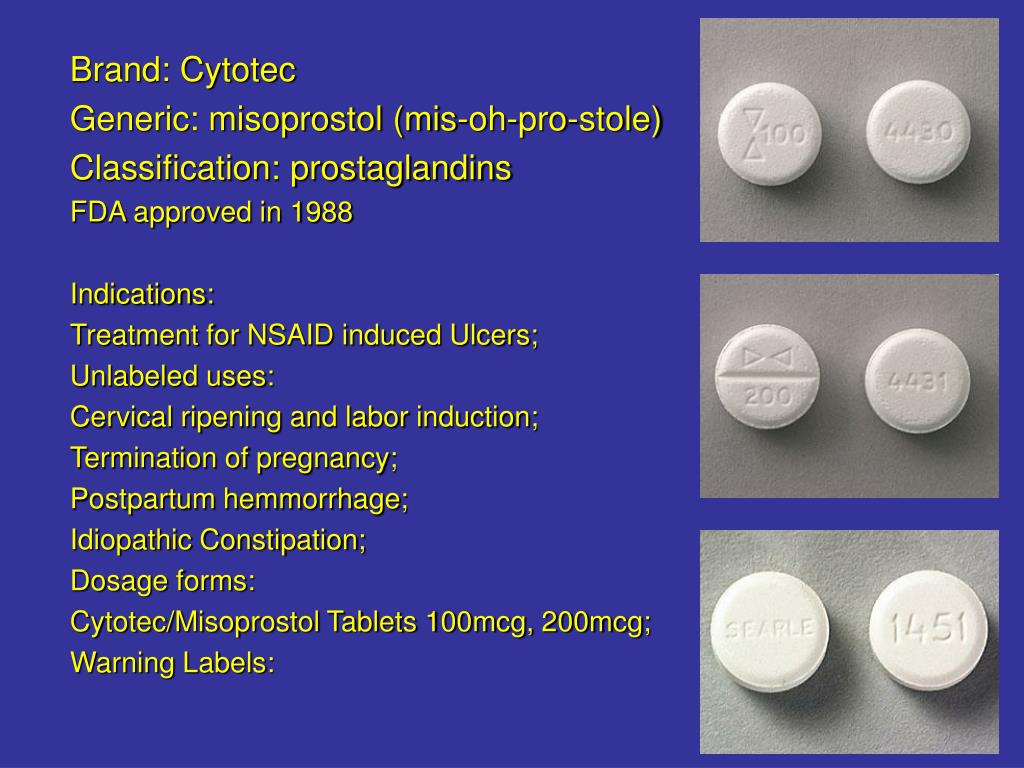

Misoprostol is a PGE1 analogue that is known to be effective in stimulating uterine contractions. Misoprostol is inexpensive and requires no special storage facilities. Several routes of administration and regimens of misoprostol have been studied, including oral (swallowed as a tablet or dissolved in a titrated solution), vaginal (inserted into the vagina as a tablet or gel), rectal (inserted into the rectum as a tablet) and buccal or sublingual (the tablet is dissolved in the cheek or under the tongue, respectively).20–22 Different routes of administration have advantages and disadvantages. Oral misoprostol achieves rapid onset of action, whereas vaginal administration is associated with slower absorption but more prolonged action. Over the past decade, slow-release misoprostol vaginal pessaries have also been tested in trials.

Although misoprostol is widely used in obstetric practice for other indications (e.g. abortion), there have been concerns about its use due to the increased risk of serious adverse effects, such as uterine rupture. Several small studies have reported excessive uterine activity that is associated with the use of misoprostol, such as uterine tachysystole (more than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes), uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting ≥ 2 minutes) and/or uterine hyperstimulation syndrome [uterine tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes such as persistent decelerations]. A meta-analysis examining the use of vaginal misoprostol suggested that despite excess uterine activity, misoprostol was not associated with adverse fetal outcomes especially at a lower dose (< 25 µg).23

Oxytocin

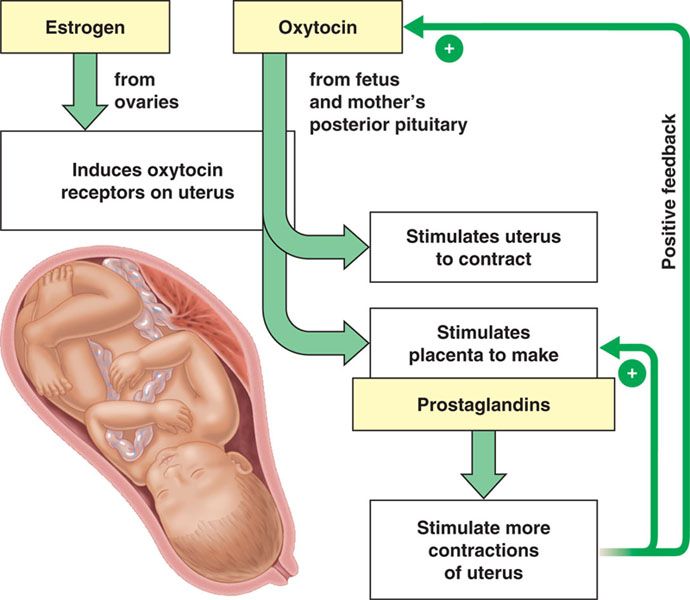

Oxytocin is a hormone that is produced naturally by the body, and which has a range of functions, including the stimulation of uterine contractions in the second and third stages of labour. Oxytocin analogues, administered intravenously, are the commonest induction agents used worldwide. Oxytocin is frequently administered when the cervix is dilated (or favourable) and may be combined with artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes (amniotomy). Oxytocin may cause excess uterine activity, especially in settings where equipment is not available to titrate doses accurately and monitor contractions.

Oxytocin analogues, administered intravenously, are the commonest induction agents used worldwide. Oxytocin is frequently administered when the cervix is dilated (or favourable) and may be combined with artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes (amniotomy). Oxytocin may cause excess uterine activity, especially in settings where equipment is not available to titrate doses accurately and monitor contractions.

Current i.v. oxytocin regimens usually involve incremental increases in dosage. Lower-dose regimens typically involve 0.5–2.0 milliunits (mU)/minute starting doses, with incremental increases of 1.0–2.0 mU/minute every 15–60 minutes. Higher-dose regimens have starting doses up to 6.0 mU/minute, with incremental increases of 2.0–6.0 mU/minute every 15–40 minutes. There are advantages and disadvantages of high- or low-dose regimens; higher doses may lead to a shorter period to delivery, but may increase the risk of hyperstimulation, whereas lower doses may increase risk of infection if labour is prolonged. 24–27

24–27

Nitric oxide donors

Nitric oxide (NO) is thought to be involved in cervical ripening, and in recent years NO donors [isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN), isosorbide dinitrate, nitroglycerin and sodium nitroprusside] have been used to promote cervical ripening. NO is administered as a vaginal tablet.28

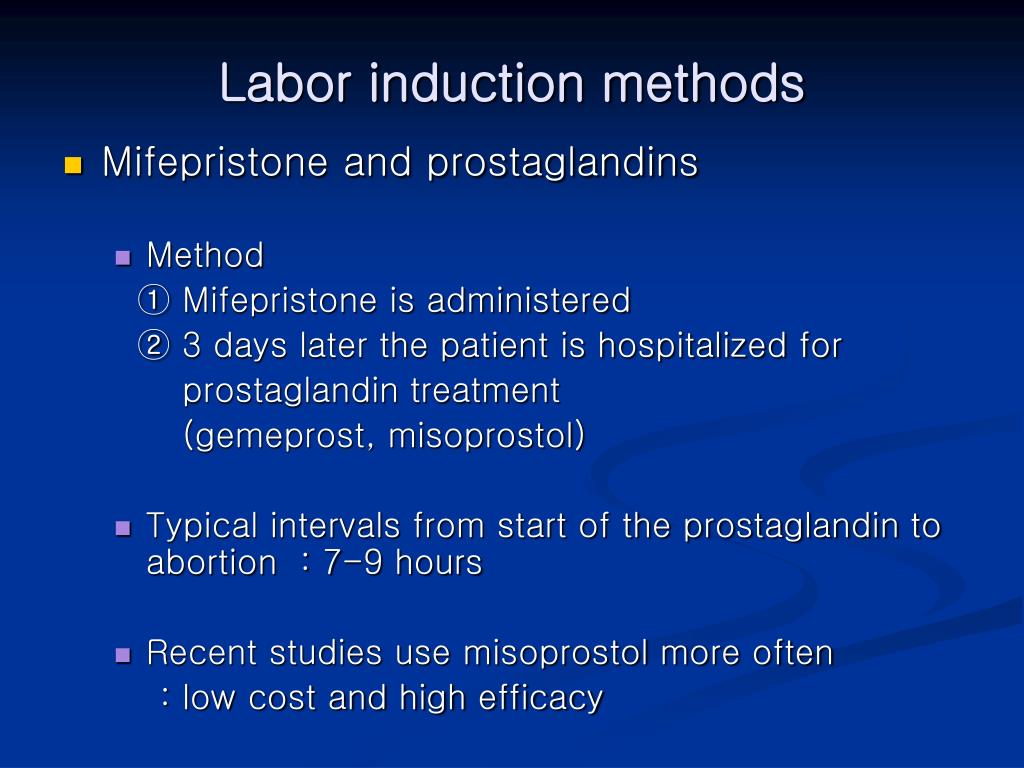

Mifepristone

Mifepristone is a progesterone antagonist that has been used in the past in combination with prostaglandins in first trimester and early second trimester pregnancy terminations. Mifepristone has been proposed as a method to induce labour because it acts to increase uterine contractions. Mifepristone is administered as an oral tablet.29

Oestrogens, corticosteroids, relaxin and hyaluronidase

Oestrogens have a role in promoting cervical ripening and, historically, have been administered intravenously or into the extra-amniotic space. There are no commercially available preparations for use in cervical ripening or induction of labour, and the two included trials of this agent date back to 196730 and 1981. 31

31

The role of corticosteroids in the process of labour is not well understood, and they are currently not used in clinical practice for the induction of labour.32

Relaxin is a hormone that is thought to encourage cervical ripening, which has been tested in a very small number of trials.33 Similarly, hyaluronidase is also thought to be implicated in cervical ripening.34 Both agents have been administered in vaginal or intracervical gel, but neither is common in current practice.

Mechanical and physical methods for induction of labour

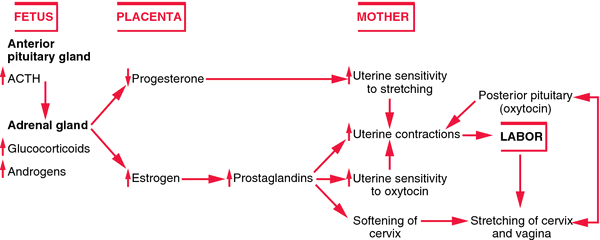

Mechanical methods to induce labour have been available for many years. Mechanical devices include various types of catheters and laminaria tents, introduced into or through the cervix and into the extra-amniotic space. The introduction of devices into the cervix may cause the cervix to dilate. Their presence may also increase prostaglandin or oxytocin secretion, which, in turn, may increase cervical dilatation and stimulate uterine contractions. 35 Here we also include descriptions of membrane sweep and amniotomy since they may be considered a physical method of inducing labour.

35 Here we also include descriptions of membrane sweep and amniotomy since they may be considered a physical method of inducing labour.

Catheters

Foley urinary catheters have been used for the induction of labour, as have double-balloon and other catheters that are specifically designed for use in induction of labour (e.g. Cook catheter). The catheter is introduced into the extra-amniotic space, and then the balloon(s) is (are) inflated to keep the catheter in place. Traction may be applied by taping the catheter to the woman’s leg. Catheters are usually left in situ until they are expelled. In some cases a saline infusion is introduced into the extra-amniotic space via the catheter.

Laminaria tents

Laminaria tents are made from sterile seaweed or synthetic materials. These devices are introduced into the cervical canal and expand to gradually stretch the cervix.

Membrane sweep

Stripping or sweeping of the membranes has been used for many years to induce labour, and continues to be carried out in many clinical settings. Membrane sweeping involves the clinician detaching the membranes from the lower uterine segment by a circular movement of the examining finger. Membrane sweeping is thought to lead to an increased production of prostaglandins. When the cervix is closed, a cervical massage may be carried out instead of a membrane sweep to stimulate the production of prostaglandins.36

Membrane sweeping involves the clinician detaching the membranes from the lower uterine segment by a circular movement of the examining finger. Membrane sweeping is thought to lead to an increased production of prostaglandins. When the cervix is closed, a cervical massage may be carried out instead of a membrane sweep to stimulate the production of prostaglandins.36

Amniotomy

During labour the amniotic membranes usually rupture spontaneously as the cervix dilates and stretches in preparation for the descent of the fetus. Amniotomy refers to rupture of the membranes using a plastic hooked instrument or, occasionally, surgical forceps.

Amniotomy may be carried out alone or in combination with oxytocin or prostaglandins to induce labour. It can be carried out only if the amniotic membranes are accessible to the midwife or doctor, and this may not happen until the cervix has started to dilate.

Amniotomy may cause some potentially serious adverse effects, including cord prolapse. The procedure may introduce infection. For women known to be human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive the procedure is avoided because it may increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.25

The procedure may introduce infection. For women known to be human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive the procedure is avoided because it may increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.25

Breast stimulation

Manual breast stimulation has been used in the past to stimulate uterine contractions.37 It is thought that it may trigger the release of oxytocin.

Sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse at term has been thought to lead to the onset of labour.38 The hypothesised mechanism of action here is the prostaglandin contained within semen.

Complementary and alternative methods for induction of labour

Castor oil

Castor oil is derived from the bean of the castor plant, and has been used in oral form as a method of stimulating labour.39 Castor oil has laxative properties, stimulating the intestines and bowel. It is this stimulation that is hypothesised to initiate uterine contractions and labour as a secondary effect.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture involves the insertion of fine needles by trained staff into the skin at specified points on the body. Stimulation of particular acupuncture points is intended to initiate uterine contractions and labour.40

Homeopathy

Homoeopathy involves the use of highly diluted solutions that contain tiny amounts of the original substance. Homeopathic preparations are popular and are available over the counter in pharmacies and health food shops. Some homeopathic preparations have been recommended to promote the onset of labour.41

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

Given the broad range of methods used to induce labour, the main research question addressed by this review is ‘what is the best method for induction of labour?‘. The specific objectives were to:

assess the effectiveness and safety of a range of induction methods to determine which method or methods achieves the best outcomes

provide a quantitative summary of the evidence on the relative effects of a broad range of induction methods to identify which method works best

develop a decision model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the different methods for induction

explore, if sufficient evidence is available, the effect of different clinical subgroups [with intact or ruptured membranes, at different gestational ages, in women following a previous CS and with low (< 6) or higher Bishop scores] on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Specification of the PICO research question

Population Pregnant women carrying a viable fetus and who are eligible for any method of third-trimester cervical ripening or labour induction.

Intervention and relevant comparators No treatment, placebo, all pharmacological (all routes and doses), mechanical and complementary methods used for the induction of labour.

Outcomes Our primary effectiveness outcome was (1) vaginal delivery (VD) not achieved within 24 hours, and our primary measures of safety were (2) uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes and (3) CS. Our secondary outcomes for serious adverse events were (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death and (5) serious maternal morbidity or death. Other outcomes included were (6) maternal satisfaction with the induction method used, and, for use in the economic model, (7) cost, resource use and utilities.

Definition of the decision problem for the economic evaluation

Our aim was to answer the following question: what is the most cost-effective method (from the interventions described above), for third-trimester cervical ripening or labour induction? Outputs from the economic evaluation include expected costs, expected benefits, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), expected net benefit and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

Stakeholder involvement in project

The steering group (listed in Appendix 1) and project team included a consumer representative, a health economist, a midwife and an obstetrician engaged in clinical practice.

A consumer representative was included as a collaborator on the project, and she contributed to the early discussions on this project and drafting the application. Induction of labour is known to be of great interest to pregnant women. In particular, women are interested in self-administered ways of initiating labour and for this reason these methods were examined in the proposed work. The consumer representative co-ordinated the involvement of members of the CPCG (Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group) consumer panel, National Childbirth Trust and the Association for Improvements in Maternity Services (AIMS) who expressed an interest in participating. Members of these groups were asked for comments to inform steering group meetings, to determine the final outcomes, to aid in the interpretation of the findings and to shape the papers to be published. The authors of this report include a consumer representative (GG).

The authors of this report include a consumer representative (GG).

The steering group commented on the study design, selection of outcomes, methods for the cost-effectiveness analysis and dissemination strategies.

Overview of report

In Chapter 2 we describe the methods used for the assessment of clinical effectiveness, including the methods for the systematic review to identify relevant evidence on clinical effectiveness, and the methods for the NMA. In Chapter 3 we present the results from the systematic review and NMA, including the relative effectiveness of interventions that have been used to induce labour in women at or near term. In Chapter 4 we describe methods and present results of the cost-effectiveness analysis, taking a UK NHS perspective. In Chapter 5 we summarise findings, set out the strengths and limitations of our approach, consider the implications of our results on recommended practice, and indicate areas for which future research would be beneficial.

Introduction - Which method is best for the induction of labour? A systematic review, network meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis

Description of the health problem

There were 698,512 live births in England and Wales in 2013.1 More than one in five births followed labour induction; this represents > 150,000 pregnant women in England2 and Wales3 per year. There is evidence that the number of labour inductions has been steadily increasing over the past two decades. NHS England maternity statistics for 2010 noted that 21.3% of births followed induction of labour, and by 2012–13 this figure had increased to 23.3%.4

Induction of labour is carried out for a number of clinical indications.5,6 The most common reasons include post-term pregnancy (defined as 41+0 weeks’ gestation), prelabour rupture of the amniotic membranes (PROM) or when the well-being of the woman or baby may be compromised by prolonging the pregnancy (e. g. in cases of fetal growth restriction or pre-eclampsia).

g. in cases of fetal growth restriction or pre-eclampsia).

There is a broad range of methods available for induction of labour. The choice of method may depend on national guidelines and local protocol, as well as individual clinical factors. The advantages and disadvantages of different methods vary, and the choice of method has implications for women and the UK NHS.

From a clinical perspective, the decision about which method to use for induction of labour can be influenced by the woman’s readiness for labour, for example whether or not membranes have ruptured spontaneously or whether or not the cervix remains undilated at the start of the induction process. Different methods used for inducing labour have different mechanisms of action, and vary in terms of how quickly birth is achieved and the likelihood of causing complications in women with different clinical characteristics. Thus, the choice of method will take into account the reason for induction and its urgency. The woman’s obstetric and medical history is also considered. For example, there is evidence that women may be more sensitive to drugs that stimulate the uterus if they have had a previous birth, and women who have a scar from a previous caesarean birth are at increased risk of uterine rupture, which can result in hysterectomy and fetal death.7

For example, there is evidence that women may be more sensitive to drugs that stimulate the uterus if they have had a previous birth, and women who have a scar from a previous caesarean birth are at increased risk of uterine rupture, which can result in hysterectomy and fetal death.7

Different methods also have different direct costs, and some methods require continuous monitoring of the woman throughout labour. Consequently, the choice of induction method may have significant implications for NHS resources, especially if the method is known to increase the risk of complications requiring a caesarean section (CS).

Women may wish to experience a natural onset of labour, and there is evidence that an induced labour can have a negative impact on their overall experience of childbirth.8 Some methods of induction are painful or unpleasant, and some are associated with distressing side effects, such as headache or nausea. Women may also have preferences about which method is used and may prefer non-pharmacological approaches. On the other hand, women will want their baby to be born safely, and timely induction may improve outcomes for women and babies.5 Women facing decisions about induction of labour require up-to-date information about the range of options available, including alternative and complementary methods.

On the other hand, women will want their baby to be born safely, and timely induction may improve outcomes for women and babies.5 Women facing decisions about induction of labour require up-to-date information about the range of options available, including alternative and complementary methods.

Description of available interventions and current service provision/policy

In the NHS context, choice of induction method is typically between prostaglandins and oxytocin combined with artificial rupture of membranes. UK clinical guidelines published in 20089 identified vaginal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) as ‘the preferred method of induction’. We note that this recommendation was not based on a quantitative overview of the evidence of the effects and safety of all available methods, or from the synthesis and analysis of data from a range of comparisons. Furthermore, this guideline9 did not recommend any particular type (gel, tablet or pessary) or dose of PGE2 because trial evidence has rarely compared different PGE2 preparations. Potential updating of the current guidance is awaiting the publication of this report.10

Potential updating of the current guidance is awaiting the publication of this report.10

Despite its importance, the question of resource use for the NHS has been relatively under-studied, and uncertainty remains about the costs that are associated with induction of labour. There is evidence that inducing labour in women with complications is associated with lower health-service costs than costs associated with expectant management.11–13 However, there is little evidence on the costs associated with specific methods of induction compared with others. Randomised trials in which one method of induction has been compared with another have only rarely included economic analyses.14

A broad range of pharmacological, mechanical, complementary and alternative methods have been used to induce labour. In the remaining sections of this chapter, we describe all of the pharmacological and mechanical methods for third-trimester induction of labour or cervical ripening which have been used in clinical practice and that have been examined in randomised trials. Complementary or alternative methods have been less commonly used in NHS settings but have been used in comparable settings in other countries. Complementary and alternative methods are included here, as information on the effects and safety of such methods may be important for women who prefer a less medicalised birth.

Complementary or alternative methods have been less commonly used in NHS settings but have been used in comparable settings in other countries. Complementary and alternative methods are included here, as information on the effects and safety of such methods may be important for women who prefer a less medicalised birth.

Pharmacological methods for the induction of labour

Prostaglandins: prostaglandin E

2 and prostaglandin F2 alphaProstaglandins are hormones produced naturally by the body that are important in the onset of labour. Synthetically manufactured prostaglandins have been used in clinical practice since the 1960s to ripen the cervix and induce uterine contractions. They are more frequently used in women when the cervix is unripe (i.e. with a Bishop score < 6). Prostaglandins promote cervical ripening and encourage the onset of labour by acting on cervical collagen so as to encourage the cervix to soften and stretch in preparation for childbirth. Prostaglandins may also stimulate uterine contractions.

Prostaglandins may also stimulate uterine contractions.

Despite the widespread use of prostaglandins as part of labour induction, they can cause a number of side effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and fever. In addition, because of their effect on the uterus, prostaglandins can cause contractions that last too long, or are too frequent or are too strong. Excessive uterine activity, or hyperstimulation, may be associated with fetal distress, and in a small number of cases can lead to uterine rupture, especially in those women who have uterine scarring from surgery or a previous caesarean birth.

A large number of prostaglandin preparations have been available for labour induction, including prostaglandin F2 alpha (PGF2α, dinoprost), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), prostaglandin E (PGE1) and misoprostol (a synthetic analogue of PGE1, which is described separately: see Misoprostol). In the past, PGF2α was frequently used in clinical practice but, more recently, PGE2 (dinoprostone) has become the most commonly used formulation. Commercially produced PGE2 analogues are expensive and require refrigeration. These factors have limited use in low-resource settings.

Commercially produced PGE2 analogues are expensive and require refrigeration. These factors have limited use in low-resource settings.

Prostaglandins are available in a variety of formulations and doses, and may be given via various routes of administration, including vaginally, intracervically, orally and, less frequently, intravenously.

Vaginal and intracervical administration

Prostaglandin preparations for vaginal and intracervical administration include gels, lactose-based vaginal tablets, suppositories, pessaries or inserts.15,16 Dosages of prostaglandins (mainly PGE2) vary, depending on route and local protocol (frequently 0.5 mg for intracervical use, 2–3 mg for intravaginal use and 10 mg for sustained-release pessaries). There is also variation in terms of the number of applications and time intervals between repeated doses. Sustained-release vaginal pessaries have been developed to reduce the number of applications and vaginal examinations that are needed during induction of labour. Vaginal and intracervical administration are the most common forms of administration in current practice.

Vaginal and intracervical administration are the most common forms of administration in current practice.

In the meta-analysis we have treated different types of vaginal and intracervical PGE2 as different interventions as different preparations may vary in terms of rate of absorption, safety and cost. We have therefore included as separate interventions:

PGE2 vaginal tablets (lactose based).

PGE2 vaginal pessaries normal release (also sometimes referred to as suppositories), manufactured using various base materials, including wax and glycerine. [Note that this intervention includes a heterogeneous group of vaginal PGE2 preparations of varying composition. The base material used was not always clear, and pessaries were frequently produced in local pharmacies (i.e. not commercially available). We included this group of interventions in the network meta-analysis (NMA) and the cost analysis for completeness, even though they are not generally reproducible or available in the UK NHS.

]

]PGE2 vaginal pessaries sustained release (10- to 12-mg pessaries, single application).

PGE2 gel introduced via vaginal applicator.

PGE2 for intracervical administration.

Extra-amniotic administration

The administration of extra-amniotic prostaglandin gel was first carried out in the early 1970s. The gel is administered via a Foley catheter inserted through the cervix into the extra-amniotic space. The catheter is frequently left in place with the balloon inflated, and light traction may also be applied by taping the catheter to the woman’s leg. Extra-amniotic administration is no longer common in current practice.17

Intravenous administration

Intravenous (i.v.) prostaglandins are associated with increased rates of maternal vomiting and diarrhoea and are rarely used in current practice.18

Oral administration

Oral PGE2 and PGF2α have been available since the early 1970s. Oral administration is associated with gastrointestinal side effects and is seldom used nowadays.19

Oral administration is associated with gastrointestinal side effects and is seldom used nowadays.19

Misoprostol

Misoprostol is a PGE1 analogue that is known to be effective in stimulating uterine contractions. Misoprostol is inexpensive and requires no special storage facilities. Several routes of administration and regimens of misoprostol have been studied, including oral (swallowed as a tablet or dissolved in a titrated solution), vaginal (inserted into the vagina as a tablet or gel), rectal (inserted into the rectum as a tablet) and buccal or sublingual (the tablet is dissolved in the cheek or under the tongue, respectively).20–22 Different routes of administration have advantages and disadvantages. Oral misoprostol achieves rapid onset of action, whereas vaginal administration is associated with slower absorption but more prolonged action. Over the past decade, slow-release misoprostol vaginal pessaries have also been tested in trials.

Although misoprostol is widely used in obstetric practice for other indications (e.g. abortion), there have been concerns about its use due to the increased risk of serious adverse effects, such as uterine rupture. Several small studies have reported excessive uterine activity that is associated with the use of misoprostol, such as uterine tachysystole (more than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes), uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting ≥ 2 minutes) and/or uterine hyperstimulation syndrome [uterine tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes such as persistent decelerations]. A meta-analysis examining the use of vaginal misoprostol suggested that despite excess uterine activity, misoprostol was not associated with adverse fetal outcomes especially at a lower dose (< 25 µg).23

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a hormone that is produced naturally by the body, and which has a range of functions, including the stimulation of uterine contractions in the second and third stages of labour. Oxytocin analogues, administered intravenously, are the commonest induction agents used worldwide. Oxytocin is frequently administered when the cervix is dilated (or favourable) and may be combined with artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes (amniotomy). Oxytocin may cause excess uterine activity, especially in settings where equipment is not available to titrate doses accurately and monitor contractions.

Oxytocin analogues, administered intravenously, are the commonest induction agents used worldwide. Oxytocin is frequently administered when the cervix is dilated (or favourable) and may be combined with artificial rupture of the amniotic membranes (amniotomy). Oxytocin may cause excess uterine activity, especially in settings where equipment is not available to titrate doses accurately and monitor contractions.

Current i.v. oxytocin regimens usually involve incremental increases in dosage. Lower-dose regimens typically involve 0.5–2.0 milliunits (mU)/minute starting doses, with incremental increases of 1.0–2.0 mU/minute every 15–60 minutes. Higher-dose regimens have starting doses up to 6.0 mU/minute, with incremental increases of 2.0–6.0 mU/minute every 15–40 minutes. There are advantages and disadvantages of high- or low-dose regimens; higher doses may lead to a shorter period to delivery, but may increase the risk of hyperstimulation, whereas lower doses may increase risk of infection if labour is prolonged. 24–27

24–27

Nitric oxide donors

Nitric oxide (NO) is thought to be involved in cervical ripening, and in recent years NO donors [isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN), isosorbide dinitrate, nitroglycerin and sodium nitroprusside] have been used to promote cervical ripening. NO is administered as a vaginal tablet.28

Mifepristone

Mifepristone is a progesterone antagonist that has been used in the past in combination with prostaglandins in first trimester and early second trimester pregnancy terminations. Mifepristone has been proposed as a method to induce labour because it acts to increase uterine contractions. Mifepristone is administered as an oral tablet.29

Oestrogens, corticosteroids, relaxin and hyaluronidase

Oestrogens have a role in promoting cervical ripening and, historically, have been administered intravenously or into the extra-amniotic space. There are no commercially available preparations for use in cervical ripening or induction of labour, and the two included trials of this agent date back to 196730 and 1981. 31

31

The role of corticosteroids in the process of labour is not well understood, and they are currently not used in clinical practice for the induction of labour.32

Relaxin is a hormone that is thought to encourage cervical ripening, which has been tested in a very small number of trials.33 Similarly, hyaluronidase is also thought to be implicated in cervical ripening.34 Both agents have been administered in vaginal or intracervical gel, but neither is common in current practice.

Mechanical and physical methods for induction of labour

Mechanical methods to induce labour have been available for many years. Mechanical devices include various types of catheters and laminaria tents, introduced into or through the cervix and into the extra-amniotic space. The introduction of devices into the cervix may cause the cervix to dilate. Their presence may also increase prostaglandin or oxytocin secretion, which, in turn, may increase cervical dilatation and stimulate uterine contractions. 35 Here we also include descriptions of membrane sweep and amniotomy since they may be considered a physical method of inducing labour.

35 Here we also include descriptions of membrane sweep and amniotomy since they may be considered a physical method of inducing labour.

Catheters

Foley urinary catheters have been used for the induction of labour, as have double-balloon and other catheters that are specifically designed for use in induction of labour (e.g. Cook catheter). The catheter is introduced into the extra-amniotic space, and then the balloon(s) is (are) inflated to keep the catheter in place. Traction may be applied by taping the catheter to the woman’s leg. Catheters are usually left in situ until they are expelled. In some cases a saline infusion is introduced into the extra-amniotic space via the catheter.

Laminaria tents

Laminaria tents are made from sterile seaweed or synthetic materials. These devices are introduced into the cervical canal and expand to gradually stretch the cervix.

Membrane sweep

Stripping or sweeping of the membranes has been used for many years to induce labour, and continues to be carried out in many clinical settings. Membrane sweeping involves the clinician detaching the membranes from the lower uterine segment by a circular movement of the examining finger. Membrane sweeping is thought to lead to an increased production of prostaglandins. When the cervix is closed, a cervical massage may be carried out instead of a membrane sweep to stimulate the production of prostaglandins.36

Membrane sweeping involves the clinician detaching the membranes from the lower uterine segment by a circular movement of the examining finger. Membrane sweeping is thought to lead to an increased production of prostaglandins. When the cervix is closed, a cervical massage may be carried out instead of a membrane sweep to stimulate the production of prostaglandins.36

Amniotomy

During labour the amniotic membranes usually rupture spontaneously as the cervix dilates and stretches in preparation for the descent of the fetus. Amniotomy refers to rupture of the membranes using a plastic hooked instrument or, occasionally, surgical forceps.

Amniotomy may be carried out alone or in combination with oxytocin or prostaglandins to induce labour. It can be carried out only if the amniotic membranes are accessible to the midwife or doctor, and this may not happen until the cervix has started to dilate.

Amniotomy may cause some potentially serious adverse effects, including cord prolapse. The procedure may introduce infection. For women known to be human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive the procedure is avoided because it may increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.25

The procedure may introduce infection. For women known to be human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive the procedure is avoided because it may increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.25

Breast stimulation

Manual breast stimulation has been used in the past to stimulate uterine contractions.37 It is thought that it may trigger the release of oxytocin.

Sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse at term has been thought to lead to the onset of labour.38 The hypothesised mechanism of action here is the prostaglandin contained within semen.

Complementary and alternative methods for induction of labour

Castor oil

Castor oil is derived from the bean of the castor plant, and has been used in oral form as a method of stimulating labour.39 Castor oil has laxative properties, stimulating the intestines and bowel. It is this stimulation that is hypothesised to initiate uterine contractions and labour as a secondary effect.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture involves the insertion of fine needles by trained staff into the skin at specified points on the body. Stimulation of particular acupuncture points is intended to initiate uterine contractions and labour.40

Homeopathy

Homoeopathy involves the use of highly diluted solutions that contain tiny amounts of the original substance. Homeopathic preparations are popular and are available over the counter in pharmacies and health food shops. Some homeopathic preparations have been recommended to promote the onset of labour.41

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

Given the broad range of methods used to induce labour, the main research question addressed by this review is ‘what is the best method for induction of labour?‘. The specific objectives were to:

assess the effectiveness and safety of a range of induction methods to determine which method or methods achieves the best outcomes

provide a quantitative summary of the evidence on the relative effects of a broad range of induction methods to identify which method works best

develop a decision model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the different methods for induction

explore, if sufficient evidence is available, the effect of different clinical subgroups [with intact or ruptured membranes, at different gestational ages, in women following a previous CS and with low (< 6) or higher Bishop scores] on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Specification of the PICO research question

Population Pregnant women carrying a viable fetus and who are eligible for any method of third-trimester cervical ripening or labour induction.

Intervention and relevant comparators No treatment, placebo, all pharmacological (all routes and doses), mechanical and complementary methods used for the induction of labour.

Outcomes Our primary effectiveness outcome was (1) vaginal delivery (VD) not achieved within 24 hours, and our primary measures of safety were (2) uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes and (3) CS. Our secondary outcomes for serious adverse events were (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death and (5) serious maternal morbidity or death. Other outcomes included were (6) maternal satisfaction with the induction method used, and, for use in the economic model, (7) cost, resource use and utilities.

Definition of the decision problem for the economic evaluation

Our aim was to answer the following question: what is the most cost-effective method (from the interventions described above), for third-trimester cervical ripening or labour induction? Outputs from the economic evaluation include expected costs, expected benefits, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), expected net benefit and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

Stakeholder involvement in project

The steering group (listed in Appendix 1) and project team included a consumer representative, a health economist, a midwife and an obstetrician engaged in clinical practice.

A consumer representative was included as a collaborator on the project, and she contributed to the early discussions on this project and drafting the application. Induction of labour is known to be of great interest to pregnant women. In particular, women are interested in self-administered ways of initiating labour and for this reason these methods were examined in the proposed work. The consumer representative co-ordinated the involvement of members of the CPCG (Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group) consumer panel, National Childbirth Trust and the Association for Improvements in Maternity Services (AIMS) who expressed an interest in participating. Members of these groups were asked for comments to inform steering group meetings, to determine the final outcomes, to aid in the interpretation of the findings and to shape the papers to be published. The authors of this report include a consumer representative (GG).

The authors of this report include a consumer representative (GG).

The steering group commented on the study design, selection of outcomes, methods for the cost-effectiveness analysis and dissemination strategies.

Overview of report

In Chapter 2 we describe the methods used for the assessment of clinical effectiveness, including the methods for the systematic review to identify relevant evidence on clinical effectiveness, and the methods for the NMA. In Chapter 3 we present the results from the systematic review and NMA, including the relative effectiveness of interventions that have been used to induce labour in women at or near term. In Chapter 4 we describe methods and present results of the cost-effectiveness analysis, taking a UK NHS perspective. In Chapter 5 we summarise findings, set out the strengths and limitations of our approach, consider the implications of our results on recommended practice, and indicate areas for which future research would be beneficial.

Makarov I.O. • Modern methods of preparing the body for childbirth, labor induction and labor stimulation

"SonoAce Ultrasound" magazine

Contains up-to-date clinical information on ultrasonography and is aimed at ultrasound diagnostic doctors, published since 1996.

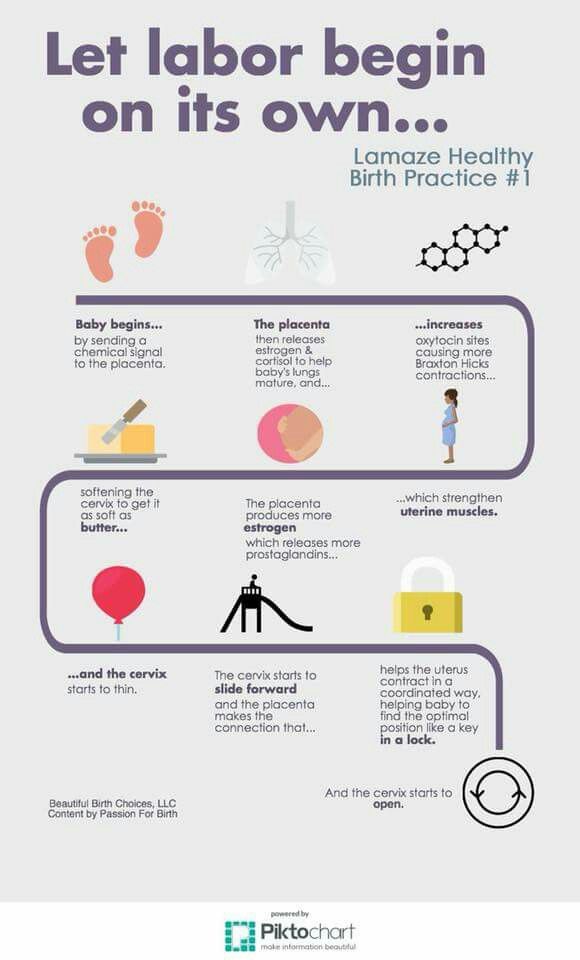

Modern principles of preparation for childbirth and their management should ensure the birth of not only a live, but also a healthy child. Accordingly, the further physical development and health of the child largely depends on the success of the preparation for childbirth and the quality of their conduct. For the effective onset and further progression of normal labor activity, one of the important conditions is the presence of a "mature" cervix, which reflects the readiness of the mother's body and the fetus for childbirth. With an "immature" cervix, labor induction and intensification of labor cannot be carried out because of the danger of a violation of the contractile activity of the uterus, the occurrence of hypoxia and fetal injury.

Prostaglandins

According to modern concepts, the preparation of the cervix for childbirth occurs not only under the influence of hormones, but primarily under the action of substances called prostaglandins. In this case, we are talking about two types: prostaglandin E2 and F2α. So, in particular, prostaglandin E2 is produced by the fetal part of the placenta, in the body of the fetus, and also in the tissues of the cervix. It helps to change the structure of the tissues of the cervix, ensuring its maturation, and also has a certain relaxing effect on the isthmus, cervix and lower segment of the uterus. Upon reaching the proper degree of maturation of the cervix, under the influence of prostaglandin E2, the development of labor activity gradually begins. Therefore, it is prostaglandin E2 that plays the starting role of the onset of labor. Prostaglandin F2α is produced in the maternal part of the placenta and in the walls of the uterus. It supports the labor activity that has already begun, providing the strongest and most effective reducing effect, helps to limit blood loss during childbirth.

To prepare the cervix for childbirth, the most physiologically justified and rational is the use of natural stimulants for the development of labor activity, i.e. preparations containing prostaglandin E2. The introduction of prostaglandin E2 should lead to both maturation of the cervix and cause contractions of the myometrium, being the starting point for the onset of labor. To prevent excessively strong contractile activity of the uterus, when using prostaglandin E2, it is necessary to achieve a balance between the maturation of the cervix and the degree of its maturity, on the one hand, and stimulation of the contractile activity of the uterus, on the other. In this regard, the local application of prostaglandin E2 by injecting the drug into the cervical canal or into the posterior vaginal fornix is the most preferable.

The topical application of prostaglandins became widespread after the development of special gels containing the required dose of the drug. Usually, to achieve sufficient maturity of the cervix and prepare it for childbirth, prostaglandin gel is injected into the cervical canal. For the successful use of the drug and the prevention of possible complications when using it, a number of conditions must be observed, as well as adhere to the relevant indications and contraindications. Thus, the need to use a prostaglandin gel to prepare the cervix arises in the absence of the biological readiness of the body for childbirth (immature cervix) and there are indications for urgent delivery in case of various obstetric or other complications (for example, in the case of prolonged pregnancy, preeclampsia, fetoplacental insufficiency, etc.). ).

For the successful use of the drug and the prevention of possible complications when using it, a number of conditions must be observed, as well as adhere to the relevant indications and contraindications. Thus, the need to use a prostaglandin gel to prepare the cervix arises in the absence of the biological readiness of the body for childbirth (immature cervix) and there are indications for urgent delivery in case of various obstetric or other complications (for example, in the case of prolonged pregnancy, preeclampsia, fetoplacental insufficiency, etc.). ).

Contraindications for the use of the drug are: the presence of a scar on the uterus after caesarean section or after other operations on the uterus; placenta previa; multiple pregnancy; pronounced signs of violation of the condition of the fetus; narrow pelvis; leakage of amniotic fluid; allergy to prostaglandins; asthma; increased intraocular pressure. Prostaglandin gel is used only in a hospital in the following cases: the presence of an immature or insufficiently mature cervix; a whole fetal bladder; absence of contraindications for childbirth through the natural birth canal.

Labor induction, preparation of the cervix

Before using the drug, it is necessary to determine the condition of the cervix, pulse and respiration rate, blood pressure, as well as assess the condition of the fetus and the contractile activity of the uterus. The gel is injected into the cervical canal in the position of the pregnant woman on her back, under the control of mirrors. To prevent leakage of the gel, the pregnant woman is left in the supine position for 30 minutes.

During the subsequent observation of the patient, monitoring of the contractile activity of the uterus and the condition of the fetus is carried out. Assess the condition of the cervix (every 2-3 hours), pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate. Under the influence of the drug, not only the maturation of the cervix occurs, labor can begin. In this case, after reaching a sufficient degree of maturity and opening the cervix by at least 4 cm, the fetal bladder is opened if it has not opened on its own before. Most often, after the application of a prostaglandin gel in the first 3-4 hours, more than half of the patients already have noticeable changes in the condition of the cervix. At the same time, it shortens and softens, located along the axis of the pelvis. In the next 3 hours (6 hours after the injection of the gel), a mature cervix is observed in another 1/3 of the patients. In many patients, on average after 9-10 hour labor activity develops. In the event that after applying the gel for 6 hours, the cervix remains immature, the drug is administered again at the same dose.

Most often, after the application of a prostaglandin gel in the first 3-4 hours, more than half of the patients already have noticeable changes in the condition of the cervix. At the same time, it shortens and softens, located along the axis of the pelvis. In the next 3 hours (6 hours after the injection of the gel), a mature cervix is observed in another 1/3 of the patients. In many patients, on average after 9-10 hour labor activity develops. In the event that after applying the gel for 6 hours, the cervix remains immature, the drug is administered again at the same dose.

A maximum of three injections of gel within 24 hours. With prenatal or early rupture of amniotic fluid, repeated administration of the gel is contraindicated, and further childbirth is carried out depending on the obstetric situation. Effective use of the gel is considered when a sufficient degree of maturity of the cervix is reached within 12 hours, and the onset of labor within 24 hours from the moment of its introduction. Usually, after applying the gel, the contractile activity of the uterus is normal, while there are no pathological changes in blood pressure and pulse rate in the mother, and there are no signs of fetal disorders.

Usually, after applying the gel, the contractile activity of the uterus is normal, while there are no pathological changes in blood pressure and pulse rate in the mother, and there are no signs of fetal disorders.

For induction of labor with a sufficient degree of maturity of the cervix, it is advisable to use a gel containing prostaglandin E2 in the vagina. The drug is used in cases where there is a need for urgent delivery due to obstetric or some other complications. Conditions and contraindications for the use of vaginal gel are the same as for the use of prostaglandin gel for insertion into the cervical canal.

The main purpose of the introduction of this drug is, first of all, the development of labor. As an additional effect, its positive effect on the process of maturation of the cervix with its insufficient readiness for childbirth is noted. In the subsequent observation and management of patients, the following principles must be observed: every 3 hours after the introduction of the vaginal gel, the condition of the cervix is assessed. If the opening of the cervix occurs less than 3 cm after 6 hours from the moment of gel administration, or there is no regular labor activity during this period of time, then the drug is administered again 1 or 2 more times, also with an interval of 6 hours. If spontaneous opening of the membranes occurs before the expiration of 6 hours from the moment of the last administration of the gel, the drug is no longer administered. If, after the administration of the drug, the cervix opens by at least 4 cm with regular labor, it is possible to open the fetal bladder, but not earlier than 6 hours after the administration of the gel. If necessary, it is possible to administer oxytocin intravenously for rhodostimulation, however, not earlier than 6 hours after the injection of the gel.

If the opening of the cervix occurs less than 3 cm after 6 hours from the moment of gel administration, or there is no regular labor activity during this period of time, then the drug is administered again 1 or 2 more times, also with an interval of 6 hours. If spontaneous opening of the membranes occurs before the expiration of 6 hours from the moment of the last administration of the gel, the drug is no longer administered. If, after the administration of the drug, the cervix opens by at least 4 cm with regular labor, it is possible to open the fetal bladder, but not earlier than 6 hours after the administration of the gel. If necessary, it is possible to administer oxytocin intravenously for rhodostimulation, however, not earlier than 6 hours after the injection of the gel.

In the process of monitoring a woman in labor, monitor the fetal condition, contractile activity of the uterus, control the pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate. Correction of weak contractile activity of the uterus and ineffective labor activity should include the use of the most effective medications in accordance with scientific data on the mechanisms of development of labor activity.

In obstetric practice, to enhance the contractile activity of the uterus in case of weakness of labor forces, various drugs are used that are administered intravenously. The most popular among them is still oxytocin. However, in some cases, for example, with an insufficiently mature cervix and prenatal rupture of amniotic fluid, it is possible to use an intravenous drip of a drug containing prostaglandin E2. And with the primary weakness of labor, it is advisable to intravenously drip the drug containing prostaglandin F2α.

Features of the use of oxytocin

The results of the studies indicate that in the process of artificially strengthening the contractile activity of the uterus, the anti-stress resistance of the fetus decreases, and its protective and adaptive capabilities are suppressed. At the same time, the use of oxytocin to enhance labor activity has the least favorable effect on the course of labor, the condition of the fetus and newborn in comparison with drugs containing prostaglandins E2 and F2α, which are used for the same purpose and in a similar obstetric situation.

The adverse effect of oxytocin can be especially pronounced in cases where the fetus experienced hypoxia even before the onset of labor, and the administration of oxytocin lasted more than 3 hours. The findings highlight the high health risk of the newborn with long-term use of oxytocin. The combined intravenous use of a solution containing prostaglandin F2α and oxytocin at half the dosage has a milder effect on the fetus, and is appropriate if it is necessary to increase contractions in the active phase of labor.

Labor stimulation

Labor stimulation with drugs containing prostaglandin E2 allows you to achieve the best effect in case of primary weakness of labor, insufficient maturity of the cervix and prenatal rupture of amniotic fluid. To achieve the best effect from the introduction of drugs to correct the weakness of labor, certain principles and conditions must be observed. So, before rhodostimulation, it is important to exclude a narrow pelvis, inferiority of the uterine wall due to numerous or complicated induced abortions or inflammatory processes.

The use of labor stimulation is contraindicated in the presence of a scar on the uterus after caesarean section or other operations, as well as in the unsatisfactory condition of the fetus. Labor stimulation should, as it were, imitate the natural development of labor in order to achieve the physiological rate of labor. In the process of rhodostimulation, constant monitoring of the condition of the fetus and the contractile activity of the uterus is carried out. The duration of rhodostimulation should not exceed 3-4 hours. If excessive contractile activity of the uterus occurs or if the condition of the fetus worsens against the background of the administration of drugs, rhodostimulation is stopped.

"SonoAce Ultrasound" magazine

Contains up-to-date clinical information on ultrasonography and is aimed at ultrasonographers, published since 1996.

Induction of labor or induction of labor

The purpose of this information material is to familiarize the patient with the induction of labor procedure and to provide information on how and why it is performed.

In most cases, labor begins between the 37th and 42nd weeks of pregnancy. Such births are called spontaneous. If drugs or medical devices are used before the onset of spontaneous labor, then the terms "stimulated" or "induced" labor are used in this case.

Labor should be induced when further pregnancy is for some reason unsafe for the mother or baby and it is not possible to wait for spontaneous labor to begin.

The goal of stimulation is to start labor by stimulating uterine contractions.

When inducing labor, the patient must be in the hospital so that both mother and baby can be closely monitored.

Labor induction methods

The choice of labor induction method depends on the maturity of the cervix in the patient, which is assessed using the Bishop scale (when viewed through the vagina, the position of the cervix, the degree of its dilatation, consistency, length, and the position of the presenting part of the fetus in the pelvic area are assessed). Also important is the medical history (medical history) of the patient, for example, a past caesarean section or operations on the uterus.

Also important is the medical history (medical history) of the patient, for example, a past caesarean section or operations on the uterus.

The following methods are used to induce (stimulate) labor:

- Oral misoprostol is a drug that is a synthetic analogue of prostaglandins found in the body. It prepares the body for childbirth, under its action the cervix becomes softer and begins to open.

- Balloon Catheter - A small tube is placed in the cervix and the balloon attached to the end is filled with fluid to apply mechanical pressure to the cervix. When using this method, the cervix becomes softer and begins to open. The balloon catheter is kept inside until it spontaneously exits or until the next gynecological examination.

- Amniotomy or opening of the fetal bladder - in this case, during a gynecological examination, when the cervix has already dilated sufficiently, the fetal bladder is artificially opened. When the amniotic fluid breaks, spontaneous uterine contractions will begin, or intravenous medication may be used to stimulate them.

- Intravenously injected synthetic oxytocin - acts similarly to the hormone of the same name produced in the body. The drug is given by intravenous infusion when the cervix has already dilated (to support uterine contractions). The dose of the drug can be increased as needed to achieve regular uterine contractions.

When is it necessary to induce labor?

Labor induction is recommended when the benefits outweigh the risks.

Induction of labor may be indicated in the following cases:

- The patient has a comorbid condition complicating pregnancy (eg, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, or some other condition).

- The duration of pregnancy is already exceeding the norm - the probability of intrauterine death of the fetus increases after the 42nd week of pregnancy.

- Fetal-related problems, eg, problems with fetal development, abnormal amount of amniotic fluid, changes in fetal condition, various fetal disorders.

- If the amniotic fluid has broken and uterine contractions have not started within the next 24 hours, there is an increased risk of inflammation in both the mother and the fetus. This indication does not apply in case of preterm labor, when preparation of the baby's lungs with a special medicine is necessary before delivery.

- Intrauterine fetal death.

What are the risks associated with labor induction?

Labor induction is not usually associated with significant complications.

Occasionally, after receiving misoprostol, a patient may develop fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, and excessive uterine contractions (tachysystole). In case of too frequent contractions to relax the uterus, the patient is injected intravenously relaxing muscles uterus medicine. It is not safe to use misoprostol if you have had a previous caesarean section as there is a risk of rupture of the uterine scar.