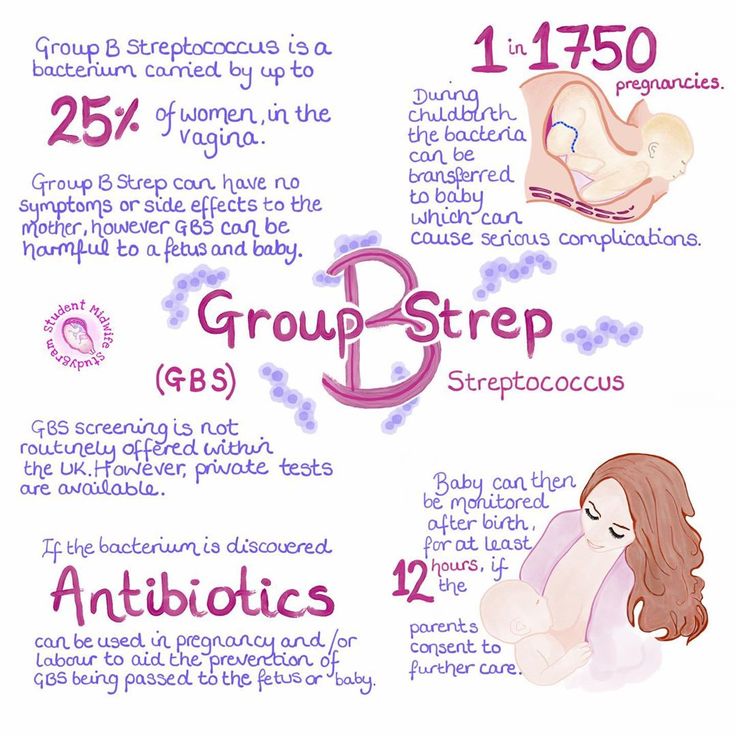

Positive for gbs during pregnancy

Group B Strep and Pregnancy (for Parents)

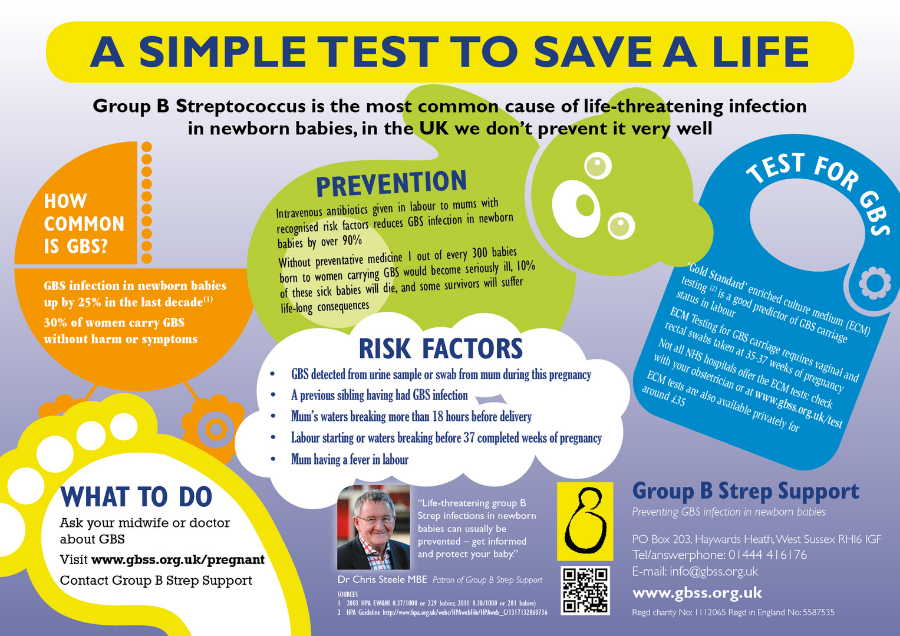

What Is Group B Strep?

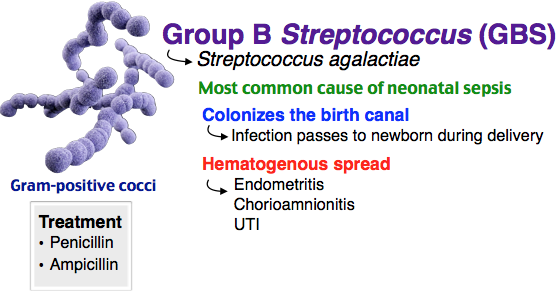

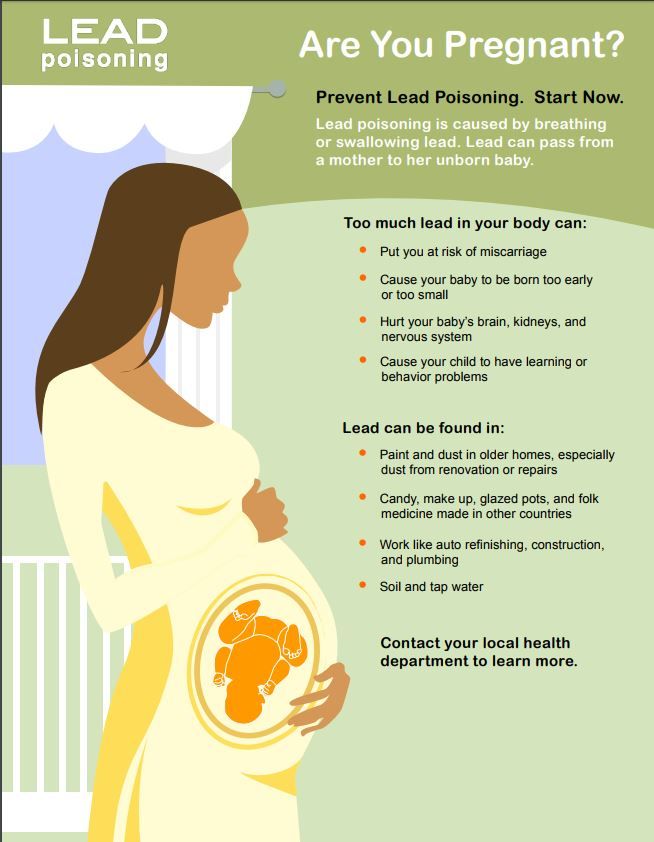

Group B Streptococcus (group B strep, GBS) is a type of

bacteriaoften found in the urinary tract, digestive system, and reproductive tracts. The bacteria come and go from our bodies, so most people who have it don't know that they do. GBS usually doesn't cause health problems.

What Problems Can Group B Strep Cause?

Health problems from GBS are not common. But it can cause illness in some people, such as the elderly and those with some medical conditions. GBS can cause infections in such areas of the body as the blood, lungs, skin, or bones.

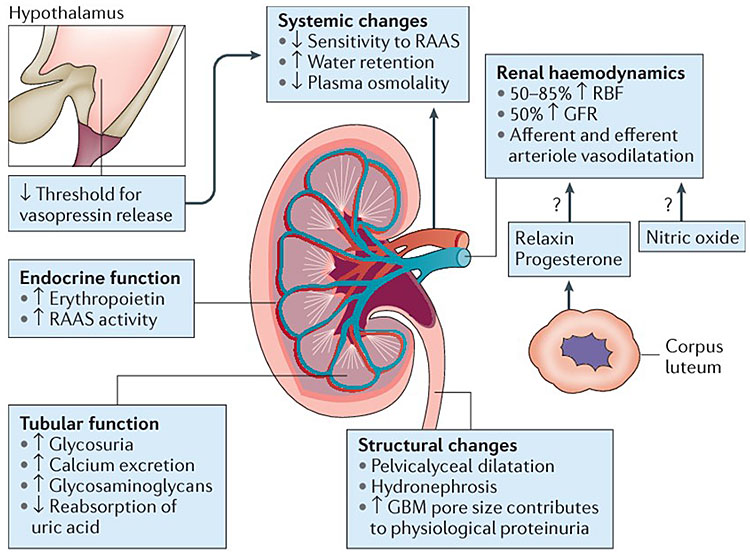

About 1 out of every 4 women have GBS. In pregnant women, GBS can cause infection of the urinary tract, placenta, womb, and amniotic fluid.

Even if they haven't had any symptoms of infection, pregnant women can pass the infection to their babies during labor and delivery.

How Does Group B Strep Affect Babies?

When women with GBS are treated with antibiotics during labor, most of their babies do not have any problems. But some babies can become very sick from GBS. Premature babies are more likely to be infected with GBS than full-term babies because their bodies and immune systems are less developed.

The two types of GBS disease in babies are:

- Early-onset infections, which happen during the first week of life. Babies often have symptoms within 24 hours of birth.

- Late-onset infections, which develop weeks to months after birth. This type of GBS disease is not well understood.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of GBS Disease?

Newborns and infants with GBS disease might show these signs:

- a fever

- feeding problems

- breathing problems

- irritability or fussiness

- inactivity or limpness

- trouble keeping a healthy body temperature

Babies with GBS disease can develop serious problems, such as:

- pneumonia

- sepsis

- meningitis (infection of the fluid and lining around the brain).

Meningitis is more common with late-onset GBS disease and, in some cases, can lead to hearing loss, vision loss, learning disabilities, seizures, and even death.

Meningitis is more common with late-onset GBS disease and, in some cases, can lead to hearing loss, vision loss, learning disabilities, seizures, and even death.

How Is Group B Strep Diagnosed?

Pregnant women are routinely tested for GBS late in the pregnancy, usually between weeks 35 and 37. The test is simple, inexpensive, and painless. Called a culture, it involves using a large cotton swab to collect samples from the vagina and rectum. These samples are tested in a lab to check for GBS. The results are usually available in 1 to 3 days.

If a test finds GBS, the woman is said to be "GBS-positive." This means only that she has the bacteria in her body — not that she or her baby will become sick from it.

GBS infection in babies is diagnosed by testing a sample of blood or spinal fluid. But not all babies born to GBS-positive mothers need testing. Most healthy babies are simply watched to see if they have signs of infection.

How Is Group B Strep Treated?

Doctors will test a pregnant woman to see if she has GBS. If she does, she will get intravenous (IV) antibiotics during labor to kill the bacteria. Doctors usually use penicillin, but can give other medicines if a woman is allergic to it.

If she does, she will get intravenous (IV) antibiotics during labor to kill the bacteria. Doctors usually use penicillin, but can give other medicines if a woman is allergic to it.

It's best for a woman to get antibiotics for at least 4 hours before delivery. This simple step greatly helps to prevent the spread of GBS to the baby.

Doctors also might give antibiotics during labor to a pregnant woman if she:

- goes into labor prematurely, before being tested for GBS

- hasn't been tested for GBS and her water breaks 18 or more hours before delivery

- hasn't been tested for GBS and has a fever during labor

- had a GBS bladder infection during the pregnancy

- had a baby before with GBS disease

Giving antibiotics during labor helps to prevent early-onset GBS disease only. The cause of late-onset disease isn't known, so no method has yet been found to prevent it. Researchers are working to develop a vaccine to prevent GBS infection.

Babies who get GBS disease are treated with antibiotics. These are started as soon as possible to help prevent problems. These babies also may need other treatments, like breathing help and IV fluids.

How Can I Help Prevent Group B Strep Infection?

Because GBS comes and goes from the body, a woman should be tested for it during each pregnancy. Women who are GBS-positive and get antibiotics at the right time during labor do well, and most don't pass the infection to their babies.

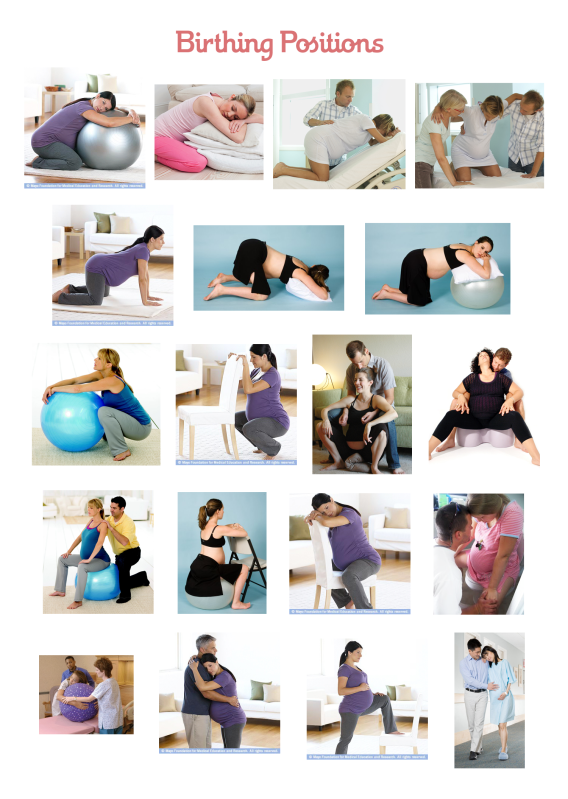

If you are GBS-positive and begin to go into labor, go to the hospital rather than laboring at home. By getting IV antibiotics for at least 4 hours before delivery, you can help protect your baby against early-onset GBS disease.

Reviewed by: Thinh Phu Nguyen, MD

Date reviewed: July 2022

Group B Strep In Pregnancy: Test, Risks & Treatment

Overview

What is group B strep?

Group B strep infection (also GBS or group B Streptococcus) is caused by bacteria typically found in a person's vagina or rectal area. About 25% of pregnant people have GBS, but don't know it because it doesn't cause symptoms. A pregnant person with GBS can pass the bacteria to their baby during vaginal delivery. Infants, older adults or people with a weakened or underdeveloped immune system are more likely to develop complications from group B strep.

About 25% of pregnant people have GBS, but don't know it because it doesn't cause symptoms. A pregnant person with GBS can pass the bacteria to their baby during vaginal delivery. Infants, older adults or people with a weakened or underdeveloped immune system are more likely to develop complications from group B strep.

Most newborns who get GBS don't become sick. However, the bacteria can cause severe and even life-threatening infections in a small percentage of newborns. Healthcare providers screen for group B strep as part of your routine prenatal care. If you test positive, your provider will treat you with antibiotics.

How do you get group B strep?

GBS bacteria naturally occur in areas of your body like your intestines and genital and urinary tracts. Adults can't get it from person-to-person contact or from sharing food or drinks with an infected person. Experts aren't entirely sure why the bacteria spreads, but they know that it’s potentially harmful in babies and people with weakened immune systems.

When do you get tested for group B strep?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine screening for group B strep in all pregnancies. You're screened for GBS between 36 and 37 weeks of pregnancy. Group B strep testing involves your provider taking a swab of your vagina and rectum and then sending it to a lab for analysis.

Can Group B strep affect a developing fetus?

GBS doesn't affect the fetus baby while it's still inside your uterus. However, your baby can get GBS from you during labor and delivery. Taking antibiotics for GBS reduces your chances of passing it to your baby.

How does a baby get GBS?

There are two main types of Group B strep in babies:

- Early-onset infection: Most (75%) babies with GBS become infected in the first week of life. GBS infection is usually apparent within a few hours after birth. Premature babies face greater risk if they become infected, but most babies who get GBS are full-term.

- Late-onset infection: GBS infection can also occur in infants one week to three months after birth. Late-onset infection is less common and is less likely to result in a baby's death than early-onset infection.

How common is GBS?

Group B strep screening during pregnancy has decreased the number of cases. According to the CDC, about 930 babies get early-onset GBS, and 1,050 get late-onset GBS. About 4% of babies who develop GBS will die from it.

Symptoms and Causes

What are the symptoms of group B strep?

Most adults don't experience symptoms of group B strep. It can cause symptoms in older people or people with certain medical conditions, but this is rare. These symptoms include:

- Fever, chills and fatigue.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Chest pains.

- Muscle stiffness.

Newborns with GBS have symptoms like:

- Fever.

- Difficulty feeding.

- Irritability.

- Breathing difficulties.

- Lack of energy.

These symptoms can become serious quickly because newborns lack immunity. Group B strep infection can lead to severe problems like sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis in infants.

Can I pass group B strep to my partner?

Other people that live with you, including other children, aren't at risk of getting sick.

Diagnosis and Tests

Will I be tested for group B strep?

Yes, your healthcare provider will test you for GBS late in your pregnancy, around weeks 36 to 37.

Your obstetrician uses a cotton swab to obtain samples of cells from your vagina and rectum. This test doesn't hurt and takes less than a minute. Then, the sample is sent to a lab where it's analyzed for group B strep. Most people receive their results within 48 hours. A positive culture result means you're a GBS carrier, but it doesn't mean that you or your baby will become sick.

If you’re using a midwife, you might be given instructions on how to test yourself at home and submit the swab to a lab.

Is Group B strep an STI?

No, group B strep isn't an STI (sexually transmitted infection). The type of bacteria that causes GBS naturally lives in your vagina or rectum. It doesn't cause symptoms for most people.

Management and Treatment

What happens if you test positive for group B strep during pregnancy?

Healthcare providers prevent GBS infection in your baby by treating you with intravenous (IV) antibiotics during labor and delivery. The most common antibiotic to treat group B strep is penicillin or ampicillin. Giving you an antibiotic at this time helps prevent the spread of GBS from you to your newborn. It's not effective to treat GBS earlier than at delivery. The antibiotics work best when given at least four hours before delivery. About 90% of infections are prevented with this type of treatment.

One exception to the timing of treatment is when GBS is detected in urine. When this is the case, oral antibiotic treatment begins when GBS is identified (regardless of the stage of pregnancy). Antibiotics should still be given through an IV during labor.

Antibiotics should still be given through an IV during labor.

Any pregnant person who has previously given birth to a baby who developed a GBS infection or who has had a urinary tract infection in this pregnancy caused by GBS will also be treated during labor.

How is group B strep treated in newborns?

Some babies still get GBS infections despite testing and antibiotic treatment during labor. Healthcare providers might take a sample of the baby's blood or spinal fluid to see if the baby has GBS infection. If your baby has GBS, they're treated with antibiotics through an IV.

Prevention

How can I reduce my risk of group B strep?

Anyone can get GBS. Some people are at higher risk due to certain medical conditions or age. The following factors increase your risk for having a baby born with group B strep:

- You tested positive for GBS.

- You develop a fever during labor.

- More than 18 hours pass between your water breaking and your baby being born.

- You have medical conditions like diabetes, heart disease or cancer.

Getting screened for GBS and taking antibiotics (if you're positive) is the best way to protect your baby from infection.

Outlook / Prognosis

What are long term problems of Group B strep in newborns?

Infants with GBS can develop meningitis, pneumonia or sepsis. These illnesses can be life-threatening. Most infants don't develop any long-term issues; however, about 25% of babies with meningitis caused by GBS develop cerebral palsy, hearing problems, learning disabilities or seizures.

Can I get tested for group B strep again?

No, once you test positive for GBS, you're considered positive for the rest of your pregnancy. You will not get re-tested.

Do I need treated for group B strep if I am having a c-section?

No, you don't need antibiotics if you're having a c-section delivery. However, you'll still be tested for GBS because labor could start before your scheduled c-section. If your water breaks and you're GBS positive, your baby is at risk of contracting the disease.

If your water breaks and you're GBS positive, your baby is at risk of contracting the disease.

Living With

When should I see my healthcare provider if I’m positive for group B strep?

In some cases, GBS causes infections during pregnancy. Symptoms of infection include fever, pain and increased heart rate. Let your provider know if you have any of those symptoms as it could lead to preterm labor.

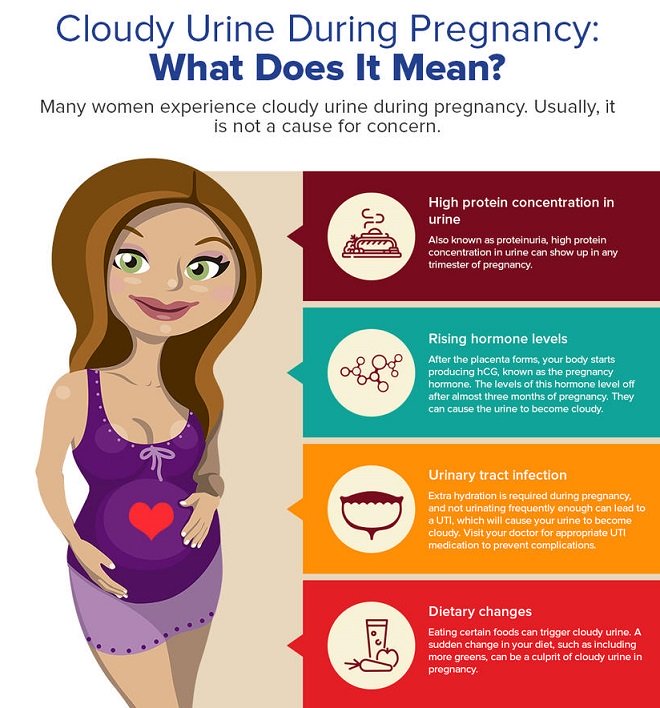

GBS can also cause urinary tract infection (UTI), which requires oral antibiotics.

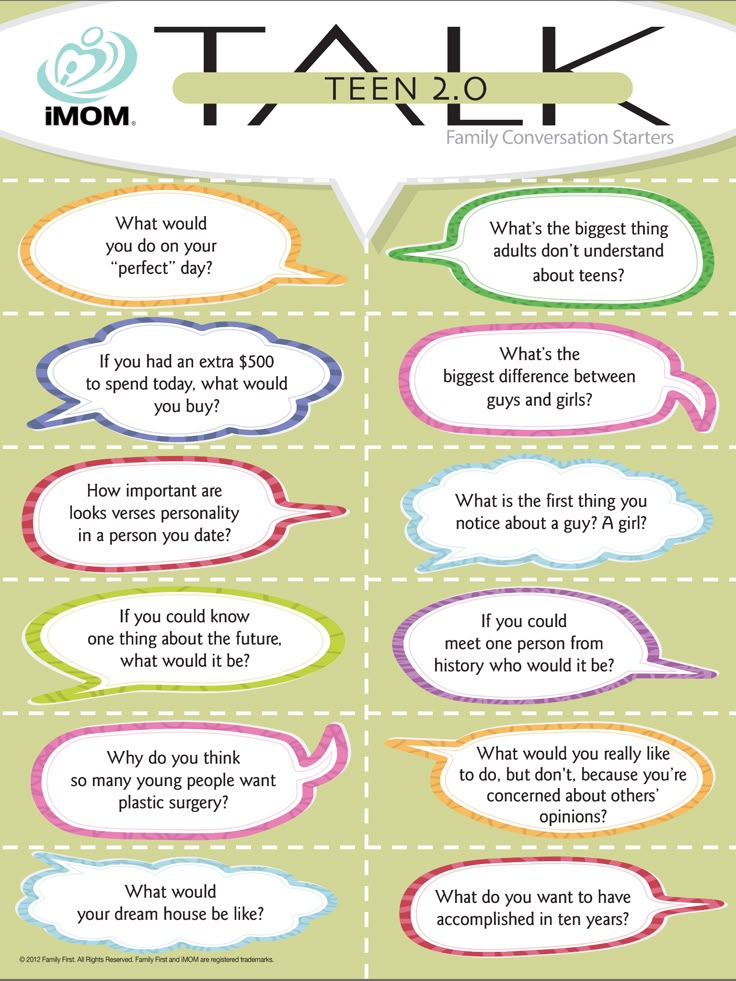

Talk to your provider about what you can expect during labor and delivery if you have group B strep.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Try not to panic if your healthcare provider tells you you're positive for group B strep during pregnancy. It's caused by bacteria that occur naturally in your body, not by anything you did wrong. The chances of you passing group B strep to your baby are quite low, especially if you take antibiotics during labor. Talk to your provider about group B strep and share any concerns you have. In most cases, testing positive for GBS causes no problems, and your baby is healthy.

In most cases, testing positive for GBS causes no problems, and your baby is healthy.

Infections during pregnancy. Detection of group B streptococcus

05/16/2017

Infections during pregnancy that can be transmitted from mother to fetus deserve great attention, as they carry a potential risk of infection of the fetus or newborn and may lead to undesirable consequences. In addition, the diagnosis of infections during pregnancy has certain characteristics due to the asymptomatic course of most maternal infections or non-specific signs and symptoms. nine0003

Group B Streptococcus (GBS, Streptococcus agalactiae ) - Causes severe neonatal illness and poses a risk to certain patients in other age groups.

It has been estimated that GBS in 30% of pregnant women can be found in the vagina and often in the urethra of their sexual partners. Despite the fact that GBS can occur as part of the normal intestinal microflora of a woman, their colonization of the urogenital tract of a pregnant woman poses a significant risk to the fetus due to the possibility of ascending infection. There is a significant relationship between the carriage of GBS in the vagina, not only with early infection of newborns (sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis), but also with premature birth, premature discharge of amniotic fluid, urinary infection in pregnant women, development of chorioamnionitis during childbirth, endometritis. nine0003

There is a significant relationship between the carriage of GBS in the vagina, not only with early infection of newborns (sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis), but also with premature birth, premature discharge of amniotic fluid, urinary infection in pregnant women, development of chorioamnionitis during childbirth, endometritis. nine0003

In the USA, Canada and European countries, regulated National programs for the prevention and treatment of GBS infections have been adopted, which are mandatory for all medical institutions.

From 01.05.17, DILA ML introduces a new study “Identification of group B streptococcus (streptococcus agalactiae) with sensitivity to antibiotics”.

| Prompt identification of pregnant women who are positive for group B streptococcus and who have risk factors for an increased chance of infection in the newborn allows to conduct intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis with the onset of labor and prevent early infection of the newborn with group B streptococcus:

|

Rules for preparation : 24 hours before the use of intravaginal and rectal medications should be excluded, before taking the biomaterial, do not wash the external genital organs.

The biomaterial is taken from two points: the lower third of the vagina and the next - the rectum, the overall result is evaluated. nine0059 Detection of group B streptococcus is carried out by a cultural method with the determination of sensitivity to antibiotics.

Research period: 6 days (Kyiv), 7.5 days (Regions).

Adequate assessment of the risk of infection of the newborn with group B streptococcus will significantly reduce the possibility of complications and ensure a favorable pregnancy outcome.

Literature:

1. Australasian society for infectious diseases, 2014

2. Antibiotic Prevention for Maternal Group B Streptococcal Colonization on Neonatal GBS-Related Adverse Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis, Shunming Li, Jingya Huang, 2017.

3. Early onset Group B Streptococcal disease Queensland clinical guidelines, 2016

4. Effect of group B streptococci colonizing the urogenital tract of pregnant women on the course and outcome of pregnancy / Oganyan K.A., Zatsiorskaya S.L., Arzhanova O.N., Savicheva A.M. – St. Petersburg, 2014

5. Digest of professional medical information. Congenital and perinatal infections: prevention, diagnosis and treatment. / Catherine S. Peckham. - No. 1 (4). – 2008.

0 0

Rate satisfaction

DILA for you

Clinical Consulting Service for clinical support of doctors and patients before visiting a doctor

0-800-600-911

Practical recommendations for counseling pregnant women with group B streptococcus | Pashchenko A.A., Dzhokhadze L.S., Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Kotomina T.S., Efremov A.N.

Introduction

In the clinical practice of an obstetrician-gynecologist, there are often problems associated with determining further tactics after obtaining a urine culture result with a detected growth of colonies of group B streptococcus ( Streptococcus agalactiae ; group B streptococcus, GBS). In accordance with the clinical guidelines "Normal Pregnancy" (2020), the diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is made after receiving repeated results of urine culture (not earlier than 2 weeks after the first analysis) with an increase in colonies of bacterial agents in an amount > 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine in the absence of clinical symptoms [1], while it is noted that antibacterial treatment of detected bacteriuria reduces the risk of developing pyelonephritis, preterm labor (PR) and fetal growth retardation (FGR) [1, 2].

In accordance with the clinical guidelines "Normal Pregnancy" (2020), the diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is made after receiving repeated results of urine culture (not earlier than 2 weeks after the first analysis) with an increase in colonies of bacterial agents in an amount > 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine in the absence of clinical symptoms [1], while it is noted that antibacterial treatment of detected bacteriuria reduces the risk of developing pyelonephritis, preterm labor (PR) and fetal growth retardation (FGR) [1, 2].

Given the proven risks of S. agalactiae -associated infectious complications for the unborn child and the pregnant woman herself, the doctor is often careful when choosing further laboratory and drug tactics in such a patient. nine0003

Detection of S. agalactiae antigen at 35–37 weeks pregnancy in the discharge of the vagina or cervical canal, according to the domestic protocol "Normal pregnancy" (2020), is an absolute indication for antibacterial prevention of early neonatal infection with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid [1]. However, the question of the advisability of using antibiotic therapy when colonies of S. agalactiae are detected in the urine of pregnant women in amounts <10 5 in 1 ml or on the epithelium of the genitourinary tract during pregnancy is still open.

However, the question of the advisability of using antibiotic therapy when colonies of S. agalactiae are detected in the urine of pregnant women in amounts <10 5 in 1 ml or on the epithelium of the genitourinary tract during pregnancy is still open.

Streptococcus agalactiae refers to β-hemolytic gram-positive cocci with virulence factors such as hemolysin and a polysaccharide capsule that prevent bacterial phagocytosis. Among pregnant women, often asymptomatic rectovaginal carriage of S is noted. agalactiae is a conditional pathogen of vaginal microbiocenosis with a frequency of occurrence in the European population from 16% to 22% [3] and predominant bacterial colonization from the gastrointestinal tract. In the 1970s, a hypothesis was first formulated and a correlation was proven between perinatal morbidity, leading to early neonatal death, and persistence of S. agalactiae in pregnant women [4, 5]. The introduction of clinical guidelines on intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis into obstetric practice has reduced the incidence of neonatal sepsis due to maternal GBS carriage by 80% in the United States. According to the statistics of the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in a report for 2016, the frequency of development in the early neonatal period of meningitis and sepsis caused by bacterial agents from the group of β-hemolytic gram-positive S. agalactiae was 0.22 cases per 1000 deliveries, excluding stillbirths [6, 7].

According to the statistics of the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in a report for 2016, the frequency of development in the early neonatal period of meningitis and sepsis caused by bacterial agents from the group of β-hemolytic gram-positive S. agalactiae was 0.22 cases per 1000 deliveries, excluding stillbirths [6, 7].

S. agalactiae as a predictor of urinary tract infection, choriamnionitis and PR in pregnant women

Urinary tract infection is one of the most common extragenital pathologies in pregnant women [8]. The frequency of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy is determined at the level of 2% to 10% [7-11]. Current domestic clinical guidelines for laboratory and instrumental screening of normal pregnancy prescribe a single microbiological (cultural) study of an average portion of urine for bacterial pathogens in order to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria after 14 weeks. gestation [1]. nine0003

gestation [1]. nine0003

The lack of timely antibacterial pharmacotherapy of asymptomatic bacteriuria in 35% of cases leads to the development of an acute infectious process - pyelonephritis of pregnant women [7, 11, 12]. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of "Pyelonephritis of pregnancy" is made on the basis of a positive result of urine culture for bacterial pathogens, the presence of severe fever with chills and increased sweating, complaints of pain in the lower back with irradiation along the ureter to the thigh or abdomen and back, nausea / vomiting, pain on palpation of the costovertebral angle, as well as with a positive symptom of Pasternatsky. The predominant bacterial agent initiating an acute infectious process in the urinary tract of pregnant women is Escherichia coli ; S. agalactiae colonies are identified on average in 2.1–30% of cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women [7, 13].

The presence of S. agalactiae in urine culture can be considered as a marker of colonization of the anogenital area of a pregnant woman, which is associated with the risk of infection of the amniotic fluid, placenta and / or decidua and the development of chorioamnionitis, or intra-amniotic infection [14]. S. agalactiae is the most common bacterial agent associated with the development of chorioamnionitis, diagnosed on the basis of a hyperthermic reaction in a patient, complaints of soreness in the pregnant uterus, symptoms of tachycardia of the pregnant woman and fetus (increased basal rhythm of the CTG curve), purulent discharge from the cervix uterus and laboratory blood test data with neutrophilic leukocytosis and an increase in the level of C-reactive protein [14, 15]. nine0003

S. agalactiae is the most common bacterial agent associated with the development of chorioamnionitis, diagnosed on the basis of a hyperthermic reaction in a patient, complaints of soreness in the pregnant uterus, symptoms of tachycardia of the pregnant woman and fetus (increased basal rhythm of the CTG curve), purulent discharge from the cervix uterus and laboratory blood test data with neutrophilic leukocytosis and an increase in the level of C-reactive protein [14, 15]. nine0003

For the first time, the association of asymptomatic bacteriuria caused by the presence of S. agalactiae colonies in urine with the risk of developing PR was described by E. Kass et al. in 1960 [16]. Subsequently, this hypothesis was developed in their studies by M. Mølle et al. [17], stating that premature rupture of membranes and PT are more common in the group of patients who are GBS carriers. However, further studies by P. Meis et al. [18], with the adjustment of demographic factors and additional statistical processing of the data, revealed the lack of sufficient statistically significant evidence of the relationship between asymptomatic bacteriuria and the presence of GBS colonies and a higher risk of developing PR. nine0003

nine0003

Previously published studies on this issue have contributed to the formation of the practice of irrational pharmacotherapy of asymptomatic pregnant women with negligible concentrations of GBS in urine cultures in many international scientific obstetric communities [19].

In order to optimize and develop an evidence-based program for counseling pregnant women with rectovaginal carriage of S. agalactiae , approaches to laboratory diagnostics and drug therapy strategies in domestic obstetric and gynecological practice, we searched for medical publications in MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library . The selection criteria were: publications in English for 2015-2020, which present the results of randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis; recommendations for drug therapy and studies on the relationship between S. agalactiae - associated bacteriuria and antibiotic resistance. The following search terms were used: streptococcal infection, Streptococcus agalactiae , bacteriuria, pregnancy, antibiotic resistance, maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

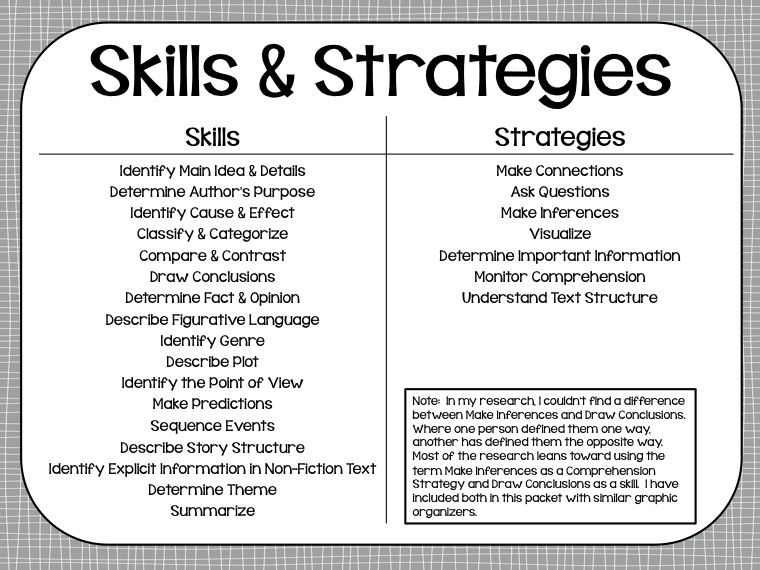

Nine articles [12, 13, 20–26] met the selection criteria (see table).

We conducted a literature review in order to develop optimal tactics for the management (observation and treatment) of pregnant women who are carriers of S. agalactiae depending on the concentration of the bacterial agent in the urine culture. An analysis of the clinical recommendations of international and national medical communities has shown different approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria associated with the presence of S. agalactiae colonies [6, 11]. Previously published scientific studies have generally supported the strategy of antibiotic therapy in patients carrying S. agalactiae at any concentration and at any gestational age to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality [16, 17, 27], but the fact of re-colonization of GSB was noted. urethral epithelium in most pregnant women within a short time after its complete elimination [20]. nine0003

nine0003

The current data presented by us from the latest retrospective and prospective studies conducted with additional statistical processing and control of confounding errors did not demonstrate a significantly significant association between the risk of PR, a higher incidence of pyelonephritis and postpartum endometritis in pregnant women with bacteriuria associated only with the presence of S colonies. agalactiae in the absence of other bacterial agents [24–26]. J. Henderson et al. [10] in their latest publications draw attention to the individual microbiome for each woman, due to the opportunistic flora of the vagina, and its protective role for both the pregnant woman and the newborn. nine0003

The updated recommendations of ACOG and the American Society for Infectious Diseases prescribe antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria with a concentration of bacterial agents of at least 10 5 CFU / ml [2, 28–30], which is fully consistent with current domestic recommendations [1].

Taking into account the results of a systematic review of the latest publications and an analysis of current clinical recommendations from various world medical communities, we have developed a practical guide for counseling pregnant women with GBS colonization of the genitourinary system in various clinical situations for outpatient and inpatient obstetrician-gynecologists. nine0003

Clinical situation No. 1

Real-time PCR detection of vaginal discharge or cervical canal by microbiological examination of S. agalactiae colonies.

Does not require antibacterial treatment at the time of detection in asymptomatic patients.

Comment . S. agalactiae refers to opportunistic facultative anaerobic microorganisms of the vaginal and intestinal microbiocenosis. Drug treatment with positive results of microbiological studies (crops) in patients with no e0lob and clinical symptoms is an erroneous strategy, in addition, it increases the risk of antibiotic resistance. nine0003

nine0003

Etiotropic drug therapy is prescribed only in case of symptoms of bacterial or mixed vaginosis, caused, among other things, by the presence of colonies S. agalactiae and other bacterial agents, in order to relieve symptoms and reduce the risk of PR. The main symptoms of bacterial / mixed vaginosis in the presence of a predominantly anaerobic pathogenic flora are: itching and burning in the vagina, profuse discharge from the genital tract with an unpleasant odor, "key" cells in smears, a decrease in pH values in the vagina and a decrease in the number of lactobacilli. nine0003

It is necessary to record the results of microbiological examination / culture as the carriage of S. agalactiae colonies during pregnancy in the patient's exchange record.

Comment . Even a single anamnestic documented fact of the presence of S. agalactiae colonies in the urogenital tract in a pregnant woman indicates the carriage of β-hemolytic streptococcus with a risk of intranatal infection and is an indication for antibiotic prophylaxis during childbirth or when amniotic fluid is discharged in order to reduce perinatal mortality. nine0003

nine0003

Vaginal-rectal screening between the 35th and 37th weeks is optional.

Comment . ACOG recommends that vaginal-rectal screening not be performed between 36 0/7 and 37 6/7 weeks if colonies of S. agalactiae have already been isolated in vaginal or cervical fluid during pregnancy and antibacterial prophylaxis of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor activity [30]. nine0003

Antibiotic prophylaxis during childbirth is indicated.

Comment . Considering the documented presence of S. agalactiae colonies in vaginal discharge or cervical canal, this group of pregnant women must be prescribed antibiotic prophylaxis for intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor or with amniotic fluid discharge in order to reduce perinatal mortality [29, 30].

Antibiotic prophylaxis in childbirth should be carried out even after a full course of antibiotic treatment of S. agalactiae -associated infections during pregnancy, since the fact of repeated recolonization of the genitourinary tract after antibacterial exposure after a few days has been proven.

Clinical situation No. 2

Detection in urine culture of colonies S. agalactiae in any titer. nine0095

Repeat urine culture after 2 weeks. since the first analysis.

Repeated detection in the urine culture of a clinically significant concentration of bacterial agents, including colonies S. agalactiae (10 5 and more in 1 ml of the average portion of urine).

A diagnosis of asymptomatic bacteriuria is made.

Comment . In accordance with the clinical guidelines "Normal Pregnancy" (2020), the diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is made after receiving repeated urine culture with the growth of colonies of bacterial agents in the amount of > 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine (including the presence of S. agalactiae and / or other bacterial agents in the urine, for example E. coli ) in the absence of clinical symptoms.

The diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is an absolute indication for the appointment of antibiotic therapy in order to prevent the possible development of pyelonephritis, PR and IGR [12]. However, it should be noted that the presence of only one type of colonies S. agalactiae in urine, even in clinically significant amounts (> 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine) does not require an increase in the dose and the frequency of taking antibacterial drugs more than the standard weekly course [24–26].

Vaginal-rectal screening between the 35th and 37th weeks is not necessary, since during pregnancy, the isolation of S. agalactiae colonies in urine or vaginal or cervical discharge has already been noted.

Antibiotic prophylaxis during childbirth is indicated. nine0003

Comment . Despite the full course of antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria, repeated recolonization of the genitourinary tract S. agalactiae in a small amount can occur within a few days, so it is mandatory for this group of pregnant women to prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic water to improve perinatal outcomes [29, thirty].

agalactiae in a small amount can occur within a few days, so it is mandatory for this group of pregnant women to prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic water to improve perinatal outcomes [29, thirty].

Detection in the primary or repeated urine culture after 2 weeks. low concentrations of S. agalactiae and other bacterial agents (less than 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine or less than 100,000 CFU / ml).

The diagnosis of "Asymptomatic bacteriuria" is incompetent, and antibacterial therapy at the time of detection in the urine culture of pregnant women of a clinically insignificant concentration of S. agalactiae and other bacterial agents is inappropriate. nine0003

Comment . The presence of bacteriuria with a low concentration of S. agalactiae colonies (less than 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine or less than 10 5 CFU / ml) indicates maternal anogenital colonization of the urinary tract.

Given the low incidence of pyelonephritis in pregnant women, there is a significantly insignificant risk of developing PR, chorioamnionitis and postpartum endometritis associated with the presence of S. agalactiae in urine culture at low concentrations (less than 10 5 in 1 ml of an average portion of urine or less than 100,000 CFU / ml), therapy in this clinical situation is irrational and increases the risk of developing resistance to the main groups of antibiotics [ 10, 24–26, 31, 32].

It is necessary to document the results of the urine culture of the pregnant woman as a carrier of S. agalactiae colonies during pregnancy in the patient's exchange record. nine0003

Vaginal-rectal screening between the 35th and 37th weeks is not necessary, since during pregnancy, the isolation of S. agalactiae colonies in urine or vaginal or cervical discharge has already been noted.

Antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown in childbirth with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid in order to reduce perinatal mortality [29, 30].

Clinical situation No. 3

Detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) at 35–37 weeks pregnancy in the discharge of the vagina or cervical canal.

An absolute indication for antibiotic prophylaxis with the onset of labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid.

Comment . If there is no anamnestic data on the detection of colonies in the patient's exchange card S. agalactiae in the urogenital tract during pregnancy, screening is carried out for the detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) in the discharge of the cervical canal and / or vaginal contents at 35–37 weeks. pregnancy, according to domestic clinical guidelines [1].

If screening is positive, antibiotic prophylaxis should be carried out with the onset of labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid in order to reduce perinatal mortality. nine0003

Comment . In the absence of anamnestic data on the detection of colonies S. agalactiae in the genitourinary tract during pregnancy and data on the results of detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) in 35-37 weeks pregnancy, as well as in the absence of previous screening (for example, the gestational age is less than 35 weeks), an express test for the detection of S. agalactiae antigen should be performed in the emergency department of the hospital with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid to resolve the issue of conducting antibiotic prophylaxis. nine0003

In the absence of anamnestic data on the detection of colonies S. agalactiae in the genitourinary tract during pregnancy and data on the results of detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) in 35-37 weeks pregnancy, as well as in the absence of previous screening (for example, the gestational age is less than 35 weeks), an express test for the detection of S. agalactiae antigen should be performed in the emergency department of the hospital with the onset of regular labor or with the outflow of amniotic fluid to resolve the issue of conducting antibiotic prophylaxis. nine0003

With a planned operative delivery and the absence of data on the detection of colonies S. agalactiae during pregnancy, the results of screening for the detection of group B streptococcus antigen ( S. agalactiae ) at 35–37 weeks. gestation in the discharge of the vagina and cervical canal may be necessary for a neonatologist in order to differentially diagnose infectious diseases in the early neonatal period.

Principles of rational pharmacotherapy for pregnant women with S. agalactiae

For pharmacotherapy of pregnant women with S. agalactiae carriage, β-lactam antibiotics from the group of semi-synthetic penicillins are used. With a burdened allergic history with the occurrence of hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin antibiotics, culture is required to determine the sensitivity of S. agalactiae colonies to second-line antimicrobials. nine0003

Comment . In clinical practice, antibiotics from the group of protected penicillins are most often used as the drug of choice: a combination of a semi-synthetic β-lactam antibiotic and a β-lactamase inhibitor (ampicillin + sulbactam). The appointment of a combination of ampicillin + clavulanic acid is possible only after 34 weeks. gestation due to the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis due to exposure to clavulanic acid on fetal enterocytes at this stage of pregnancy. nine0003

nine0003

Second-line drugs include first-generation cephalosporins or clindamycin from the lincosamide group. Given the increase in resistance to antibacterial drugs from the group of cephalosporins and lincosamides, nitrofurantoin can be prescribed in the II and III trimesters up to 36 weeks. gestation due to increased risks of developing neonatal jaundice in newborns when taking the drug 7 days before delivery [1, 31, 32].

Intranatal antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with colonies S. agalactiae in the urogenital tract

For the purpose of antibacterial prevention of intrauterine infection with the onset of regular labor activity or with the outflow of amniotic fluid, first- or second-line drugs are prescribed intravenously every 6-8 hours, while the first dose of the drug is administered in a double dosage (with intravenous administration of antibiotics, the concentration of colonies of β-hemolytic streptococcus per epithelium of the urinary tract decreases sharply within about 2 hours). nine0003

nine0003

Intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis is the main strategy to reduce the risk of streptococcal infection in the neonatal period. A multivalent polysaccharide protein conjugate vaccine is currently being developed, which may

'edo, will become an alternative to primary intrauterine antibiotic prophylaxis of early neonatal infection and improve perinatal outcomes [32].

Principles of rational pharmacotherapy for patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria

In 2016 and 2018 WHO has issued recommendations on a 7-day antibiotic regimen for all pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria to prevent drug resistance, risk of preterm birth, and low birth weight newborns. The WHO recommendations were based on data from a Cochrane Library review that included 14 studies involving more than 2,000 people with a concentration of bacterial agents greater than 10 5 in the average portion of urine [12]. The presence in the urine of only one type of colony - S. agalactiae - in clinically significant amounts (> 10 5 in 1 ml of the average portion of urine) does not require an increase in the dose and frequency of taking antibacterial drugs more than the standard weekly course.

agalactiae - in clinically significant amounts (> 10 5 in 1 ml of the average portion of urine) does not require an increase in the dose and frequency of taking antibacterial drugs more than the standard weekly course.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic rectovaginal carriage of S. agalactiae in pregnant women is significantly associated with severe infectious complications in the early neonatal period (meningitis, neonatal sepsis), therefore, a clear balanced approach to the management of such women is required, which would ensure the birth of healthy children and would not increase the risks associated with increasing antibiotic resistance S. agalactiae , under the condition of inevitable re-colonization of the genitourinary system a few days after the administration of antibiotics. Our analysis of the current clinical recommendations of the world professional medical communities is reflected in the practical recommendations presented in this article on the optimal tactics for monitoring and treating pregnant women who are carriers of S. agalactiae in the domestic practice of an obstetrician-gynecologist.

agalactiae in the domestic practice of an obstetrician-gynecologist.

Information about authors:

Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Pashchenko — Clinical Postgraduate Student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Russian National Research Medical University named after I.I. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID iD 0000-0003-0202-2740.

Jokhadze Lela Sergeevna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Faculty of Medicine of the Russian National Research Medical University named after A.I. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID ID 0000-0001-5389-7817.

Dobrokhotova Yuliya Eduardovna — Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Russian National Research Medical University. N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID iD 0000-0002-7830-2290.

N.I. Pirogov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Ostrovityanova, 1; ORCID iD 0000-0002-7830-2290.

Kotomina Tatyana Sergeevna - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the maternity ward of the branch No. 1 of the GBUZ "City Clinical Hospital No. 52 DZM"; 123182, Russia, Moscow, st. Sosnovaya, d. 11; ORCID iD 0000-0002-5660-2380. nine0099

Efremov Alexander Nikolaevich - obstetrician-gynecologist of the postpartum department of the branch No. 1 GBUZ "City Clinical Hospital No. 52 DZM"; 123182, Russia, Moscow, st. Sosnovaya, 11.

Contact information: Pashchenko Alexander Alexandrovich, e-mail: [email protected].

Transparency of financial activities: none of the authors has a financial interest in the submitted materials or methods. nine0099

No conflict of interest.

Article received on 04/05/2021.

Received after review on 04/28/2021.

Accepted for publication on May 25, 2021.

About the authors:

Aleksandr A. Pashchenko — postgraduate student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University; 1, Ostrovityanov str., Moscow, 117437, Russian Federation; ORCID iD 0000-0003-0202-2740. nine0099

Lela S. Dhokhadze - C. Sc. (Med.), assistant of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University; 1, Ostrovityanov str., Moscow, 117437, Russian Federation; ORCID ID 0000-0001-5389-7817.

Yuliya E. Dobrokhotova - Dr. Sc. (Med.), Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University; 1, Ostrovityanov str., Moscow, 117437, Russian Federation; ORCID ID 0000-0002-7830-2290.

Tatyana S.