How to talk so your child listens

Parenting coach has 3 tips

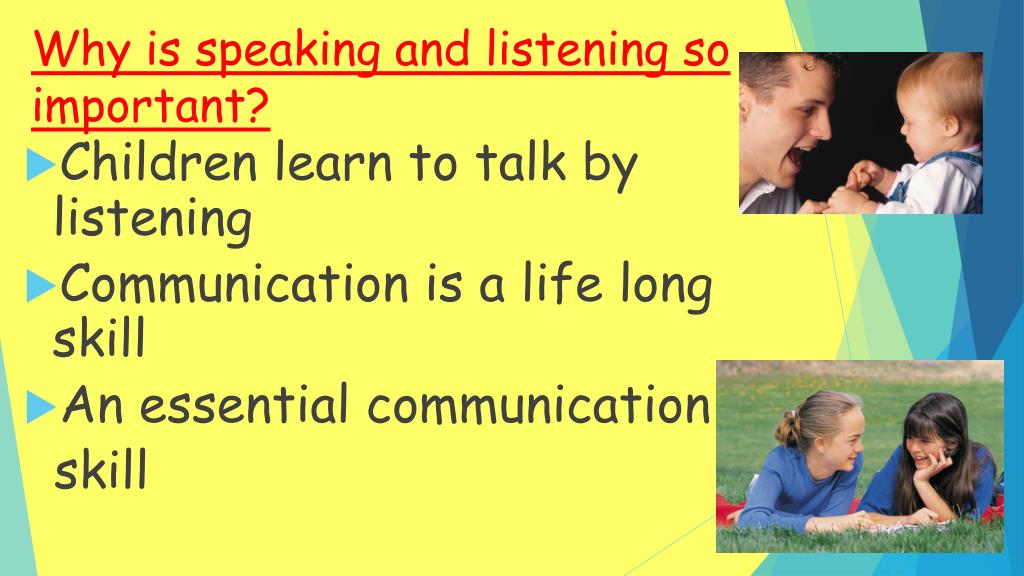

For many parents, raising a child who listens can be one of the most challenging — and important — lessons in life.

Not only is the ability to listen critical to a child's early development — enabling them to learn and keep safe from harm — but it is also vital for building relationships and achieving professional success later in life.

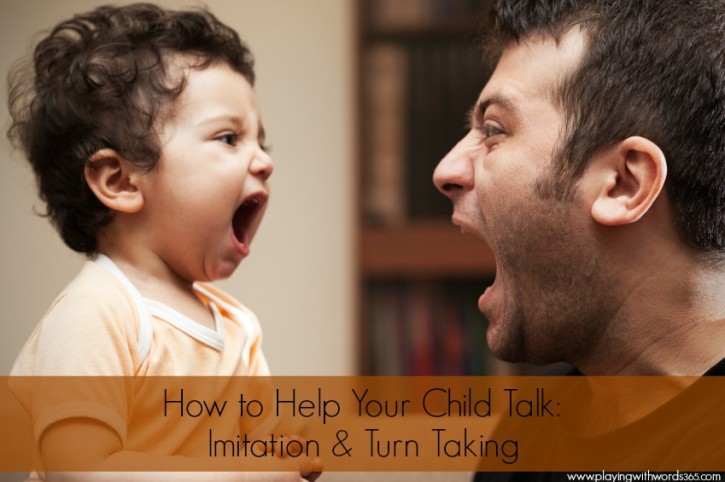

Still, so often it can feel as though a child is unable — or unwilling — to listen, leading to arguments and tantrums, with parent and child miles apart in their positions.

However, it needn't be like that, according to parenting expert and authorized "Language of Listening" coach, Camilla Miller. Describing the U.S.-founded, three-step framework as the "missing step in parenting," Miller said it can help reframe any conflict and allow a child to reach their goals within a parent's boundaries.

"You get what you want and they get what they want. It's win-win," Miller, founder of U.K.-based website and coaching business Keeping your cool parenting, told CNBC Make It.

Here are the three steps for getting your child to listen, according to Miller.

1. Say what you see

The first step in the "Language of Listening" is simple: Say what you see. Rather than imposing your judgement on your child's behavior, resist the urge to react and quite literally vocalize what you see.

For example, you may think your child is not sharing, and you wish that they were, but, in their eyes, they are busy playing. Say as much: "You're busy playing with that toy." Equally, you may think they are giving you attitude, when, in their mind, they are feeling frustrated. Acknowledge that: "You're feeling frustrated about this situation."

When your child feels unheard, they feel like you're dismissing their wants and needs.

Camilla Miller

coach, Keeping your cool parenting

"Your child needs to feel heard before they can listen to you," Miller said. "When your child feels unheard, they feel like you're dismissing their wants and needs, they think you are telling them how they feel is wrong. "

"

That doesn't mean that you need to give in to their demands. But it gives you an opportunity to step into their shoes and figure out the root cause of their behavior.

"So often as parents we go in with a demand or a request, and we haven't acknowledged what our kids want first," said Miller. "If you don't care about what they want, they won't care about what you want."

2. Offer a can-do

Once you have understood and empathized with your child's behavior, you will be in a better position to help them move forward and find a solution.

If they are displaying a behavior you don't like, help them redirect that energy toward something you do like.

Yusuke Murata | Digitalvision | Getty Images

For instance, they may be jumping on the sofa and you would prefer they didn't. Acknowledge their desire to jump around and blow off steam, but help them direct that energy to a different space like the floor or a trampoline. Alternatively, they may be demanding a new toy and their birthday has just passed. Help them think of some ways they can purchase it for themselves, such as by earning extra pocket money.

Help them think of some ways they can purchase it for themselves, such as by earning extra pocket money.

"It's about looking at the need behind the behavior and helping them to meet that need in a way that is acceptable to you," said Miller.

If, though, they are demonstrating a behavior you do like, acknowledge and enable it to help reinforce such behaviors in future.

3. Finish off with a strength

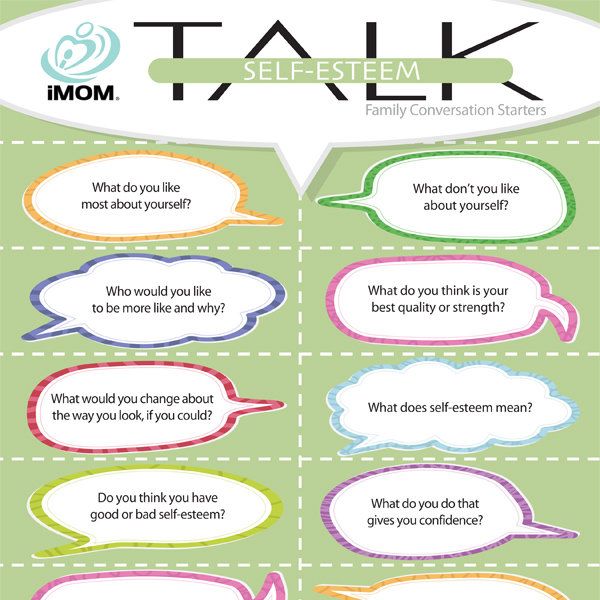

When you have deescalated the situation and reached a compromise, conclude the discussion by highlighting a strength your child has displayed.

Avoid structuring the feedback with yourself at the center, however, i.e. "I'm so happy you did that." Rather, make them the focus, for example by saying: "You're such a problem solver, you found a way to fix that."

By adopting the child's inner voice, it helps them reinforce those behaviors.

Camilla Miller

coach, Keeping your cool parenting

That way, they will recognize themselves as an active participant in the situation and one with strong decision-making capabilities, which are more likely to be repeated over time.

"By adopting the child's inner voice, it helps them reinforce those behaviors and build their self-esteem," Miller said.

Changing your own reaction

While the "Language of Listening" framework is structured principally for children, it's one that can also be applied to other age groups and situations, including teenagers, colleagues and romantic relationships, according to Miller.

In the case of teenagers, for instance, saying what you see can help them better understand themselves when they may be behaving in unusual ways, while simultaneously opening up the channels of communication with you as a parent.

"Generally, the reason people act out or shout is because of their need for power," said Miller, noting the need to respect that desire.

Meanwhile, truly listening to and being understanding of other people's perspectives can help you be more considerate and compassionate as a person, too.

"It's actually understanding your own behavior as well," continued Miller. "The quickest way to change our reaction is to change how we see things."

"The quickest way to change our reaction is to change how we see things."

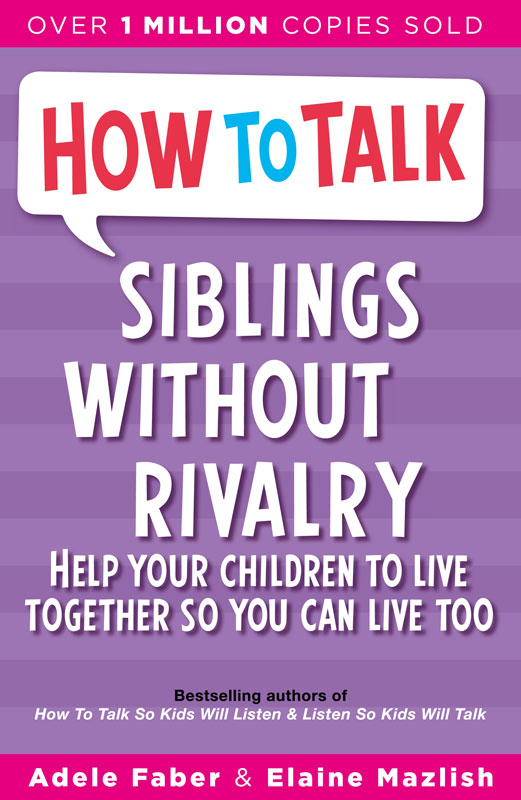

How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk | Book by Adele Faber, Elaine Mazlish | Official Publisher Page

1| Helping Children Deal with Their Feelings

PART I

I was a wonderful parent before I had children. I was an expert on why everyone else was having problems with theirs. Then I had three of my own.

Living with real children can be humbling. Every morning I would tell myself, “Today is going to be different,” and every morning was a variation of the one before: “You gave her more than me!” . . . “That’s the pink cup. I want the blue cup.” . . . “This oatmeal looks like throw-up.” . . . “He punched me.” . . . “I never touched him!” . . . “I won’t go to my room. You’re not the boss over me!”

They finally wore me down. And though it was the last thing I ever dreamed I’d be doing, I joined a parent group. The group met at a local child-guidance center and was led by a young psychologist, Dr. Haim Ginott.

Haim Ginott.

The meeting was intriguing. The subject was “children’s feelings,” and the two hours sped by. I came home with a head spinning with new thoughts and a notebook full of undigested ideas:

Direct connection between how kids feel and how they behave.

When kids feel right, they’ll behave right.

How do we help them to feel right?

By accepting their feelings!

Problem—Parents don’t usually accept their children’s feelings. For example:

“You don’t really feel that way.”

“You’re just saying that because you’re tired.”

“There’s no reason to be so upset.”

Steady denial of feelings can confuse and enrage kids. Also teaches them not to know what their feelings are—not to trust them.

After the session I remember thinking, “Maybe other parents do that. I don’t.” Then I started listening to myself. Here are some sample conversations from my home—just from a single day.

CHILD:Mommy, I’m tired.ME:You couldn’t be tired. You just napped.CHILD:(louder) But I’m tired.ME:You’re not tired. You’re just a little sleepy. Let’s get dressed.CHILD:(wailing) No, I’m tired!CHILD:Mommy, it’s hot in here.ME:It’s cold. Keep your sweater on.CHILD:No, I’m hot.ME:I said, “Keep your sweater on!”CHILD:No, I’m hot.CHILD:That TV show was boring.ME:No, it wasn’t. It was very interesting.CHILD:It was stupid.ME:It was educational.CHILD:It stunk.ME:Don’t talk that way!

Can you see what was happening? Not only were all our conversations turning into arguments, I was also telling my children over and over again not to trust their own perceptions but to rely on mine instead.

Once I was aware of what I was doing, I was determined to change. But I wasn’t sure how to go about it. What finally helped me most was actually putting myself in my children’s shoes. I asked myself, “Suppose I were a child who was tired, or hot or bored? And suppose I wanted that all-important grown-up in my life to know what I was feeling . . . ?”

. . ?”

Over the next weeks I tried to tune in to what I thought my children might be experiencing, and when I did, my words seemed to follow naturally. I wasn’t just using a technique. I really meant it when I said, “So you’re still feeling tired—even though you just napped.” Or “I’m cold, but for you it’s hot in here.” Or “I can see you didn’t care much for that show.” After all, we were two separate people, capable of having two different sets of feelings. Neither of us was right or wrong. We each felt what we felt.

For a while, my new skill was a big help. There was a noticeable reduction in the number of arguments between the children and me. Then one day my daughter announced, “I hate Grandma,” and it was my mother she was talking about. I never hesitated for a second. “That is a terrible thing to say,” I snapped. “You know you don’t mean it. I don’t ever want to hear that coming out of your mouth again.”

That little exchange taught me something else about myself. I could be very accepting about most of the feelings the children had, but let one of them tell me something that made me angry or anxious and I’d instantly revert to my old way.

I could be very accepting about most of the feelings the children had, but let one of them tell me something that made me angry or anxious and I’d instantly revert to my old way.

I’ve since learned that my reaction was not that unusual. On the following page you’ll find examples of other statements children make that often lead to an automatic denial from their parents. Please read each statement and jot down what you think a parent might say if he were denying his child’s feelings.

I. CHILD: I don’t like the new baby.

PARENT: (denying the feeling)

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

II. CHILD: I had a dumb birthday party. (After you went “all out” to make it a wonderful day.)

PARENT: (denying the feeling)

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

III. CHILD: I’m not wearing this stupid retainer anymore. It hurts. I don’t care what the orthodontist says!

CHILD: I’m not wearing this stupid retainer anymore. It hurts. I don’t care what the orthodontist says!

PARENT: (denying the feeling)

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

IV. CHILD: I hate that new coach! Just because I was one minute late he kicked me off the team.

PARENT: (denying the feeling)

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Did you find yourself writing things like:

“That’s not so. I know in your heart you really love the baby.”

“What are you talking about? You had a wonderful party—ice cream, birthday cake, balloons. Well, that’s the last party you’ll ever have!”

“Your retainer can’t hurt that much. After all the money we’ve invested in your mouth, you’ll wear that thing whether you like it or not!”

“You have no right to be mad at the coach. It’s your fault. You should have been on time.”

It’s your fault. You should have been on time.”

Somehow this kind of talk comes easily to many of us. But how do children feel when they hear it? In order to get a sense of what it’s like to have one’s feelings dismissed, try the following exercise:

Imagine that you’re at work. Your employer asks you to do an extra job for him. He wants it ready by the end of the day. You mean to take care of it immediately, but because of a series of emergencies that come up you completely forget. Things are so hectic, you barely have time for your own lunch.

As you and a few coworkers are getting ready to go home, your boss comes over to you and asks for the finished piece of work. Quickly you try to explain how unusually busy you were today.

He interrupts you. In a loud, angry voice he shouts, “I’m not interested in your excuses! What the hell do you think I’m paying you for—to sit around all day on your butt?” As you open your mouth to speak, he says, “Save it,” and walks off to the elevator.

Your coworkers pretend not to have heard. You finish gathering your things and leave the office. On the way home you meet a friend. You’re still so upset that you find yourself telling him or her what had just taken place.

Your friend tries to “help” you in eight different ways. As you read each response, tune in to your immediate “gut” reaction and then write it down. (There are no right or wrong reactions. Whatever you feel is right for you.)

I. Denial of Feelings: “There’s no reason to be so upset. It’s foolish to feel that way. You’re probably just tired and blowing the whole thing out of proportion. It can’t be as bad as you make it out to be. Come on, smile . . . You look so nice when you smile.”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

II. The Philosophical Response: “Look, life is like that. Things don’t always turn out the way we want. You have to learn to take things in stride. In this world, nothing is perfect.”

Things don’t always turn out the way we want. You have to learn to take things in stride. In this world, nothing is perfect.”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

III. Advice: “You know what I think you should do? Tomorrow morning go straight to your boss’s office and say, ‘Look, I was wrong.’ Then sit right down and finish that piece of work you neglected today. Don’t get trapped by those little emergencies that come up. And if you’re smart and you want to keep that job of yours, you’ll make sure nothing like that ever happens again.”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

IV. Questions: “What exactly were those emergencies you had that would cause you to forget a special request from your boss?”

“Didn’t you realize he’d be angry if you didn’t get to it immediately?”

“Has this ever happened before?”

“Why didn’t you follow him when he left the room and try to explain again?”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

V. Defense of the Other Person: “I can understand your boss’s reaction. He’s probably under terrible pressure. You’re lucky he doesn’t lose his temper more often.”

Defense of the Other Person: “I can understand your boss’s reaction. He’s probably under terrible pressure. You’re lucky he doesn’t lose his temper more often.”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

VI. Pity: “Oh, you poor thing. That is terrible! I feel so sorry for you, I could just cry.”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

VII. Amateur Psychoanalysis: “Has it ever occurred to you that the real reason you’re so upset by this is because your employer represents a father figure in your life? As a child you probably worried about displeasing your father, and when your boss scolded you it brought back your early fears of rejection. Isn’t that true?”

Isn’t that true?”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

VIII. An Empathic Response (an attempt to tune into the feelings of another): “Boy, that sounds like a rough experience. To be subjected to an attack like that in front of other people, especially after having been under so much pressure, must have been pretty hard to take!”

Your reaction:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

You’ve just been exploring your own reactions to some fairly typical ways that people talk. Now I’d like to share with you some of my personal reactions. When I’m upset or hurting, the last thing I want to hear is advice, philosophy, psychology, or the other fellow’s point of view. That kind of talk makes me only feel worse than before. Pity leaves me feeling pitiful; questions put me on the defensive; and most infuriating of all is to hear that I have no reason to feel what I’m feeling. My overriding reaction to most of these responses is “Oh, forget it. . . . What’s the point of going on?”

That kind of talk makes me only feel worse than before. Pity leaves me feeling pitiful; questions put me on the defensive; and most infuriating of all is to hear that I have no reason to feel what I’m feeling. My overriding reaction to most of these responses is “Oh, forget it. . . . What’s the point of going on?”

But let someone really listen, let someone acknowledge my inner pain and give me a chance to talk more about what’s troubling me, and I begin to feel less upset, less confused, more able to cope with my feelings and my problem.

I might even say to myself, “My boss is usually fair. . . . I suppose I should have taken care of that report immediately. . . . But I still can’t overlook what he did. . . . Well, I’ll go in early tomorrow and write that report first thing in the morning. . . . But when I bring it to his office I’ll let him know how upsetting it was for me to be spoken to in that way. . . . And I’ll also let him know that, from now on, if he has any criticism I would appreciate being told privately. ”

”

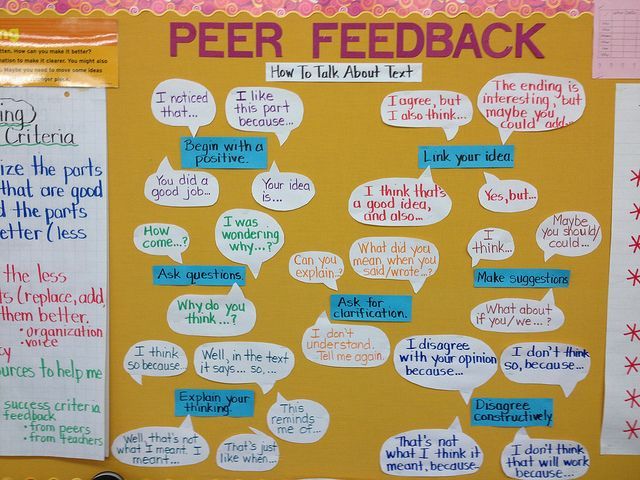

The process is no different for our children. They too can help themselves if they have a listening ear and an empathic response. But the language of empathy does not come naturally to us. It’s not part of our “mother tongue.” Most of us grew up having our feelings denied. To become fluent in this new language of acceptance, we have to learn and practice its methods. Here are some ways to help children deal with their feelings.

TO HELP WITH FEELINGS

1. Listen with full attention.

2. Acknowledge their feelings with a word—“Oh” . . . “Mmm” . . . “I see.”

3. Give their feelings a name.

4. Give them their wishes in fantasy.

On the next few pages you’ll see the contrast between these methods and the ways that people usually respond to a child who is in distress.

© 1980 Adele Faber

0008Faber & Mazlish Parenting Books

How to Talk So Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk

how to properly communicate with children. No boring theory! Only proven practical recommendations and a lot of live examples for all occasions! The authors, world-famous experts in the field of parent-child relations, share with the reader both their own experience (each of them has three adult children) and the experience of numerous parents who attended their seminars. The book will be of interest to anyone who wants to come to a complete understanding with children and forever end "generational conflicts."

No boring theory! Only proven practical recommendations and a lot of live examples for all occasions! The authors, world-famous experts in the field of parent-child relations, share with the reader both their own experience (each of them has three adult children) and the experience of numerous parents who attended their seminars. The book will be of interest to anyone who wants to come to a complete understanding with children and forever end "generational conflicts."

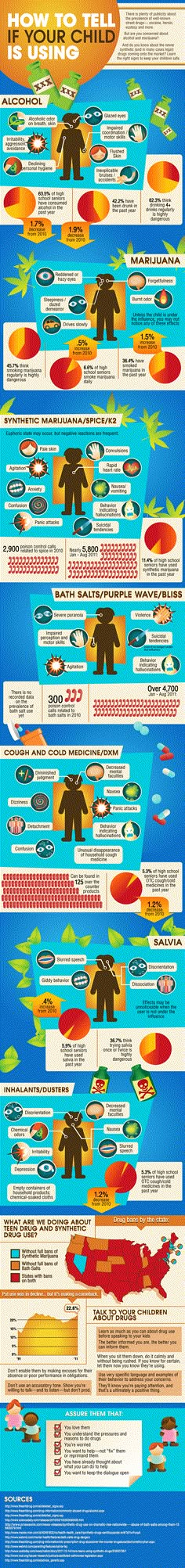

“How to talk so teenagers will listen and how to listen so teenagers will talk”

talk about difficult topics such as sex, drugs and defiant appearance, help them become independent, take responsibility for their actions and make informed, reasonable decisions.

“Brothers and sisters. How to help your children live together0009

Having another child, parents dream that the children would be friends with each other, that the elder would help the younger one, giving the mother time to rest or do other things. But in reality, the appearance of another child in the family is often accompanied by numerous childhood experiences, jealousy, resentment, quarrels and even fights.

But in reality, the appearance of another child in the family is often accompanied by numerous childhood experiences, jealousy, resentment, quarrels and even fights.

World communication experts and best-selling authors Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish decided to dedicate an entire book to this problem.

“Ideal parents in 60 minutes. Express course from the world's experts in parenting»

The long-awaited novelty from the #1 experts in communication with children Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish! Fully adapted to modern realities, the 1992 edition! In the book you will find: excerpts from the legendary technique of Faber and Mazlish - briefly the most important; analysis of difficult situations in comics; tests for "correct reaction"; practical exercises to consolidate skills; Answers to frequently asked questions from parents.

The perfect format for busy parents!

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lesley Faber and Robert Mazlish, our house consultants, who always helped us with a well-formulated phrase, a new idea, a parting word.

Thanks to Carl, Joanna and Abram Faber, Kati, Liz and John Mazlish for encouraging us to just be there.

Kati Menninger, who supervised the printing process of our manuscript with the utmost attention to detail.

Kimberly Ko, who took our scribbles and scribbled directions and sent us drawings of parents and children, which made us feel warm.

Robert Markel for his support and mentorship at critical moments.

Gerard Nirenberg, friend and advisor, who generously shared his experience and erudition.

Parents at our seminars for their written work and for their strong criticism.

Ann Marie Geiger and Patricia King, who helped us endlessly when we needed them.

To Jim Wade, our editor, whose inexhaustible good humor and concern for the quality of the book brought us joy in working with him.

Dr. Chaim Ginott, who introduced us to new ways of communicating with children. With his death, the children of the whole world lost their great protector. He loved them very much.

He loved them very much.

Letter to Readers

Dear Reader,

We never thought we'd write a "How To" book for parents about communication skills. The relationship between parents and children is very personal. The idea of giving someone instructions on how to talk to your child didn't seem quite right to us. In our first book "Free parents - free children" we tried not to teach or preach - we wanted to tell a story. The seminars that I spent years together with psychologist Dr. Chaim Ginott, a specialist in late childhood, have profoundly influenced our lives. We were sure that if we told a story about how new skills helped us to relate to our children and ourselves differently, our mood would be conveyed to readers, they would be inspired and begin to improvise themselves.

To a certain extent, this happened. Many proud parents have written to us about what they have achieved at home just by reading about our experience. There were other letters, united by a common appeal. People wanted us to write a second book with specific instructions...practical exercises...methods...tear-off reminder pages...any material to help them master the skills step by step.

People wanted us to write a second book with specific instructions...practical exercises...methods...tear-off reminder pages...any material to help them master the skills step by step.

We have seriously considered this idea for some time, but our initial doubts returned and we pushed the idea back into the background again. In addition, we were very busy and focused on the talks and workshops we were preparing for our lecture tours.

Over the next few years, we traveled around the country giving seminars to parents, teachers, school principals, medical staff, adolescents, and social workers. Everywhere we went, people shared with us their own thoughts about these new methods of communication - their doubts, disappointments and enthusiasm. We were grateful to them for their frankness and learned something from everyone. Our archive is filled to overflowing with new exciting materials.

In the meantime, mail continued to arrive not only from the United States, but also from France, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, the Philippines, and India. Ms. Anaga Ganpul from New Delhi wrote:

Ms. Anaga Ganpul from New Delhi wrote:

“I have so many problems that I would like to ask for your advice… Please tell me what can I do to study this topic in detail? I got stuck. The old methods don't suit me, and I don't have the new skills. Please help me figure this out."

It all started with this letter.

We again began to think about the possibility of writing a book that would show "how" to act. The more we talked about it, the more comfortable we got with the idea. Why not write a "how to do" book and include exercises so that parents can gain the knowledge they want?

Why not write a book that gives parents a chance at their own pace to put into practice what they have learned themselves or from a friend?

Why not write a book with a hundred examples of useful dialogue so that parents can adapt the language to their own style?

The book may include pictures that show the application of this knowledge in practice, so that anxious parents can look at the picture and quickly review what they have learned.

We could personalize the book. We would talk about our own experiences, answer the most common questions, and include stories and discoveries shared with us by parents in our groups over the past six years. But most importantly, we would always keep in mind our main goal - the constant search for methods that establish self-esteem and humanity in children and parents.

All of a sudden, our initial embarrassment about writing How To Do was gone. Every field of art and science has its own educational books. Why not write one for parents who want to learn how to talk so their kids will listen and listen so their kids will talk?

Once we decided on this, we started writing very quickly. We hope Ms Ganpul gets a free copy in New Delhi before her children grow up.

Adele Faber

Elaine Mazlish

How to read and use this book

It seems overly presumptuous of us to tell everyone how to read a book (especially since we both start reading books in the middle or even at the end). But since this is our book, we'd like to let you know how we think it should be handled. After you get used to it by scrolling through it and looking at the pictures, start with the first chapter. Do exercises as you read. Resist the temptation to skip them and move on to the "nice bits". If you have a friend with whom you can work on the exercises, that's even better. We hope you will talk, argue and discuss the answers in detail with him.

But since this is our book, we'd like to let you know how we think it should be handled. After you get used to it by scrolling through it and looking at the pictures, start with the first chapter. Do exercises as you read. Resist the temptation to skip them and move on to the "nice bits". If you have a friend with whom you can work on the exercises, that's even better. We hope you will talk, argue and discuss the answers in detail with him.

We also hope that you will write down your answers so that this book will become a personal reminder to you. Write neatly or illegibly, change your mind, cross out or erase, but write.

Read the book slowly. It has taken us more than ten years to learn everything that we tell in it. We do not urge you to read it as long, but if the methods outlined here are of interest to you, then you may want to change something in your life, then it is better to do it slowly, and not abruptly. After reading the chapter, put the book aside and give yourself a week to complete the task before moving forward again. (You might be thinking, “There’s so much to do, the last thing I need is a task!” However, experience tells us that putting knowledge into practice and recording results helps build skills.)

(You might be thinking, “There’s so much to do, the last thing I need is a task!” However, experience tells us that putting knowledge into practice and recording results helps build skills.)

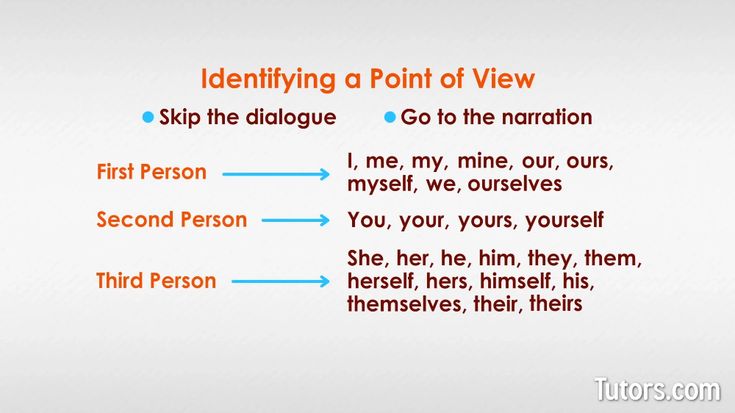

In conclusion, let's say a word about pronouns. We have tried to avoid clumsy "he/she, him/her, himself/herself", passing freely from masculine to feminine. We hope that neither sex has been neglected.

You may also wonder why some parts of the book, which has two authors, are written as if from the point of view of one person. This solved the annoying problem of constantly clarifying who is telling the story and whose experience it is. It seems to us that “I” will be easier for readers to perceive than “I, Adele Faber…” or “I, Elaine Mazlish…”. As for our conviction about the value of the ideas presented in the book, here we speak in unison. We have both seen these communication methods work in our families and thousands of others. It is our great pleasure to share them with you.

1

Helping children deal with their feelings

Chapter 1

The Four Rules

I was a great mother before I had children. I knew perfectly well why all people have problems with their children. And then I got three of my own.

Life with children can be very difficult. Every morning I told myself: “Today everything will be different,” and still it repeated the previous one. “You gave her more than me!..”, “This is a pink cup. I want a blue cup", "This oatmeal looks like vomit", "He hit me", "I didn't touch him at all!", "I won't go to my room. You are not my boss!"

Finally they got me. And although I didn’t even dream in terrible dreams that I could do such a thing, I joined the parent group. The group met at a local psychopediatrics center and was led by a young psychologist, Dr. Chaim Ginott.

The meeting turned out to be quite interesting. His theme was the feelings of a child, and two hours flew by. When I got home, my head was spinning with new thoughts, and my notebook was full of jumbled entries:

A direct link between how children feel and how they behave.

When children feel good, they behave well.

How do we help them feel good?

Accepting their feelings!

The problem is that parents usually do not understand the feelings of their children. For example: “You really feel very different”, “You are saying this because you are tired”, “There is no reason to be so upset.”

Constant denial of feelings can confuse and enrage a child. It also teaches them not to understand their feelings and not to trust them.

I remember after the meeting I thought, “Maybe other parents do that. Me not". Then I started taking care of myself. Here are a few sample conversations that took place at my home in one day.

Child. Mommy, I'm tired!

I. You couldn't get tired. You just dozed off.

Child ( louder than ). But I'm tired.

I. You are not tired. You are just a little dormouse. Let's get dressed.

Child ( yells ). No, I'm tired!

Child.

Mommy, it's hot in here.

I. It's cold here. Don't take off your sweater.

Child. No, I'm hot.

Me. I said, "Don't take off your sweater!"

Child. No, I'm hot.

Child. This TV show was boring.

Z. No, it was very interesting.

Child. It was stupid.

Z. It was instructive.

Child. It's vile.

I. Don't say that!

See what happened? In addition to the fact that all our conversations turned into arguments, I again and again urged the children not to trust their feelings, but to rely instead on mine.

One day I realized what I was doing. I decided to change. But I didn't know exactly how to do it. What finally helped me the most was trying to look at everything from a child's point of view. I asked myself, “Let’s say I was a child who is tired, hot or bored. And let's say I'd like an important adult in my life to know how I'm feeling...” the words seemed to come naturally. I didn't just use technical tricks. I really meant what I said: “So, you still feel tired, despite the fact that you just took a nap.” Or: "I'm cold, but you're hot here." Or: "I see you are not particularly interested in this TV program." Ultimately, we were two different people, capable of having two different sets of feelings. None of us were right or wrong. Each of us felt what we felt.

I didn't just use technical tricks. I really meant what I said: “So, you still feel tired, despite the fact that you just took a nap.” Or: "I'm cold, but you're hot here." Or: "I see you are not particularly interested in this TV program." Ultimately, we were two different people, capable of having two different sets of feelings. None of us were right or wrong. Each of us felt what we felt.

For some time my new knowledge has been of great help to me. The number of disputes between me and the children has noticeably decreased. Then one day my daughter announced:

- I hate my grandmother.

She was talking about to my mother . I didn't hesitate for a second.

- You can't say such horrible things! I barked. You know very well that you didn't mean it. I don't want to hear those words from you again.

This little fight taught me something else about myself. I could accept most of the feelings of the children, but as soon as one of them said something to me that would make me angry or alarmed, I immediately returned to the old line of behavior.

I have since learned that my reaction was not strange or unusual. Below you will find examples of other statements by children that often lead to automatic denial on the part of their parents. Please read each statement and write down briefly what you think parents should say if they deny their child's feelings.

1. Child. I don't like the newborn.

Parents ( denying this feeling ).

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

2. Child. It was a stupid birthday. (After you went out of your way to make this day wonderful.)

Parents ( denying this feeling ).

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

3. Child. I won't wear the record anymore. I'm in pain. I don't care what the dentist says!

Parents ( denying this feeling ).

______________

______________

______________

______________

4. Child. I was so pissed off! Only because I came two minutes late for physical education, the teacher did not introduce me to the team.

Child. I was so pissed off! Only because I came two minutes late for physical education, the teacher did not introduce me to the team.

Parents ( denying this feeling ).

______________

______________

______________

______________

You caught yourself writing:

“That's not true. I know deep down you really love your brother/sister.”

“What are you talking about? You had a wonderful birthday - ice cream, birthday cake, balloons. Okay, this is the last holiday that was arranged for you!

“Your record can't hurt you too much. After all, we've invested so much money into it that you'll wear it whether you like it or not!"

“You have no right to be angry with your teacher. This is your mistake. There was no need to be late."

For some reason, these phrases come to our mind most easily. But how do children feel when they hear them? To understand what it's like when your feelings are not taken into account, do the following exercise.

Imagine that you are at work. The boss asks to do extra work for him. He wants her to be ready by the end of the day. You are supposed to get to it immediately, but due to a series of pressing cases that have come up, you completely forgot about it. It's such a crazy day that you barely have time to eat lunch.

When you and some employees are ready to go home, your boss comes up to you and asks you to give him the finished part of the work. You quickly try to explain how busy you have been all day.

He interrupts you. In a loud, angry voice, he yells, “I'm not interested in your excuses! Why the hell do you think I'm paying you to sit on your ass all day?" As soon as you open your mouth to say something, he says, "Enough." And heads for the elevator.

Employees pretend not to hear anything. You finish packing your things and leave the office. On the way home you meet a friend. You are still so upset that you start telling him about what happened.

Your friend is trying to "help" you in eight different ways. As you read each response, tune in to an immediate spontaneous response and write it down. (There are no right or wrong reactions. Whatever you feel is normal for you.)

As you read each response, tune in to an immediate spontaneous response and write it down. (There are no right or wrong reactions. Whatever you feel is normal for you.)

1. Denial of feelings: “There is no reason to be so upset. It's stupid to feel like that. You're probably just tired and making an elephant out of a fly. It can't be as bad as you describe. Come on, smile... You're so cute when you smile."

Your reaction:

______________

______________

______________

______________

2. Philosophical answer: “Listen, this is how life is. Things don't always work out the way we want them to. You need to learn to take things calmly. Nothing is perfect in this world."

Your response:

______________

______________

______________

______________

3. Advice: "You know what I think you should do? Tomorrow morning, go to your boss's office and say: "I'm sorry, I was wrong. " Then sit down and finish the part of the work you forgot to do today. Don't get distracted by urgent matters. And if you are smart and want to keep this job for yourself, you must be sure that nothing like this will happen again.

" Then sit down and finish the part of the work you forgot to do today. Don't get distracted by urgent matters. And if you are smart and want to keep this job for yourself, you must be sure that nothing like this will happen again.

Your response:

______________

______________

______________

______________

4. Questions: “What specific urgent matters caused you to forget your boss's special request?

"Didn't you realize that he would be angry if you didn't start doing it right away?"

"Has this ever happened before?"

"Why didn't you follow him when he left the room and try to explain everything again?"

Your response:

______________

______________

______________

______________

5. Protecting another person: “I understand your boss's reaction. He's probably in terrible time trouble. You're lucky he doesn't get irritated more often."

Your reaction:

______________

______________

______________

______________

6. Pity: “Oh, poor thing. It's horrible! I sympathize with you, I'll just cry now.

Pity: “Oh, poor thing. It's horrible! I sympathize with you, I'll just cry now.

Your response: ______________

______________

______________

______________

7. Attempted psychoanalysis: “Has it occurred to you that the real reason you are upset is that your boss symbolizes the father figure in your life? As a child, you may have been afraid to displease your father, and when your boss scolded you, your early fears of rejection returned to you. This is wrong?"

Your response:

______________

______________

______________

______________

8. Empathy (trying to tune in to the other person's feelings): “Yeah, it's quite an unpleasant experience. Being subjected to such harsh criticism in front of other people, especially after such a load, is not easy to survive!

Your response:

______________

______________

______________

______________

______________

You have just studied your own reactions to some very typical ways people talk. Now I want to share with you some of my personal reactions. When I am upset or hurt, the last thing I want to hear is advice, philosophical outpourings, psychological discourse, or other points of view of people. This type of conversation will only aggravate my condition, which will become even worse than it was before. Pity makes me feel miserable, questions make me defensive, and most of all it pisses me off if I hear that I have no reason to feel the way I feel. The main reaction to all these responses is: "Okay, forget it ... What's the point of continuing?"

Now I want to share with you some of my personal reactions. When I am upset or hurt, the last thing I want to hear is advice, philosophical outpourings, psychological discourse, or other points of view of people. This type of conversation will only aggravate my condition, which will become even worse than it was before. Pity makes me feel miserable, questions make me defensive, and most of all it pisses me off if I hear that I have no reason to feel the way I feel. The main reaction to all these responses is: "Okay, forget it ... What's the point of continuing?"

But as soon as someone is willing to really listen to me, acknowledge my inner pain and give me the opportunity to talk more about what worries me, I begin to feel less upset, less puzzled, able to cope with my feelings and my problem.

I can even say to myself: “My boss is usually fair… I think I should have jumped right into this report… But I still can’t forgive him for what he did… Okay, I’ll just come early tomorrow morning and be the first I will write this report in deeds . .. But when I bring it to his office, I will let him know how upset I am because he talked to me like that ... I will also let him know that starting today, when he wants to tell me what some criticism, I will be grateful to him if he does this not in front of everyone.

.. But when I bring it to his office, I will let him know how upset I am because he talked to me like that ... I will also let him know that starting today, when he wants to tell me what some criticism, I will be grateful to him if he does this not in front of everyone.

The same with children. They, too, can help themselves if someone is willing to listen and empathize with them. But words of empathy do not come naturally to us. It is not our "mother tongue". Most of us grew up in an environment of denial of feelings. To master this new language of approval, we need to learn and practice its techniques. Here are some ways to help your child sort out their feelings.

TO HELP YOUR CHILD TO DISCOVER HIS FEELINGS

1. Listen carefully to him.

2. Share his feelings (using the words "yes ...", "hmm ...", "understood").

3. Name his feelings

4. Show that you understand the desires of the child, give him what he wants in fantasy.

In the following pictures, you will see the contrast between these techniques and how people usually respond to children when they have problems.

Now you have four possible ways to give first aid to a child with a problem: listen to him with full attention, acknowledge his feelings in words, name his feelings, understand the child’s desires by giving him what he wants in the form of fantasy.

But more important than all words is our attitude. If we do not treat children with empathy, then no matter what we say, the child will feel that we are deceiving him or manipulating him. Only when our words are filled with sincere empathy do we speak directly to the child's heart.

Of the four skills we have illustrated, the most difficult is the ability to listen to children's outpourings and then "name the feeling." It takes practice and focused attention to get into what the child is saying and determine what he or she may be experiencing. In addition, it is very important to give the child a vocabulary to describe his inner reality. Once he has words to describe the feeling, he can help himself.

In addition, it is very important to give the child a vocabulary to describe his inner reality. Once he has words to describe the feeling, he can help himself.

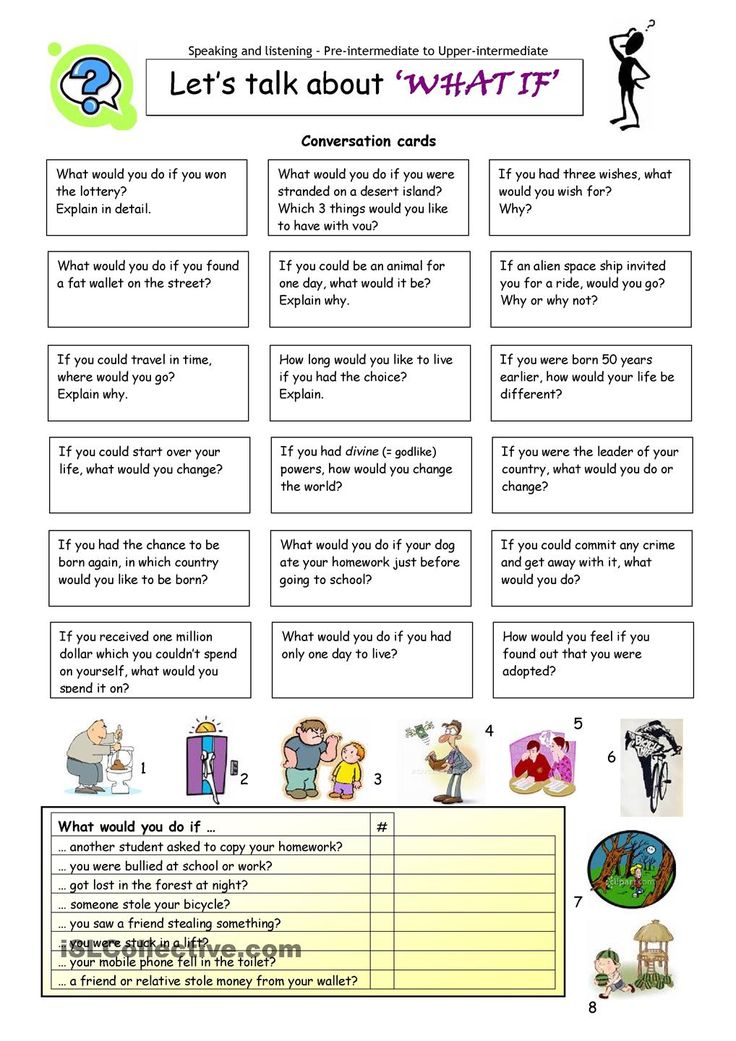

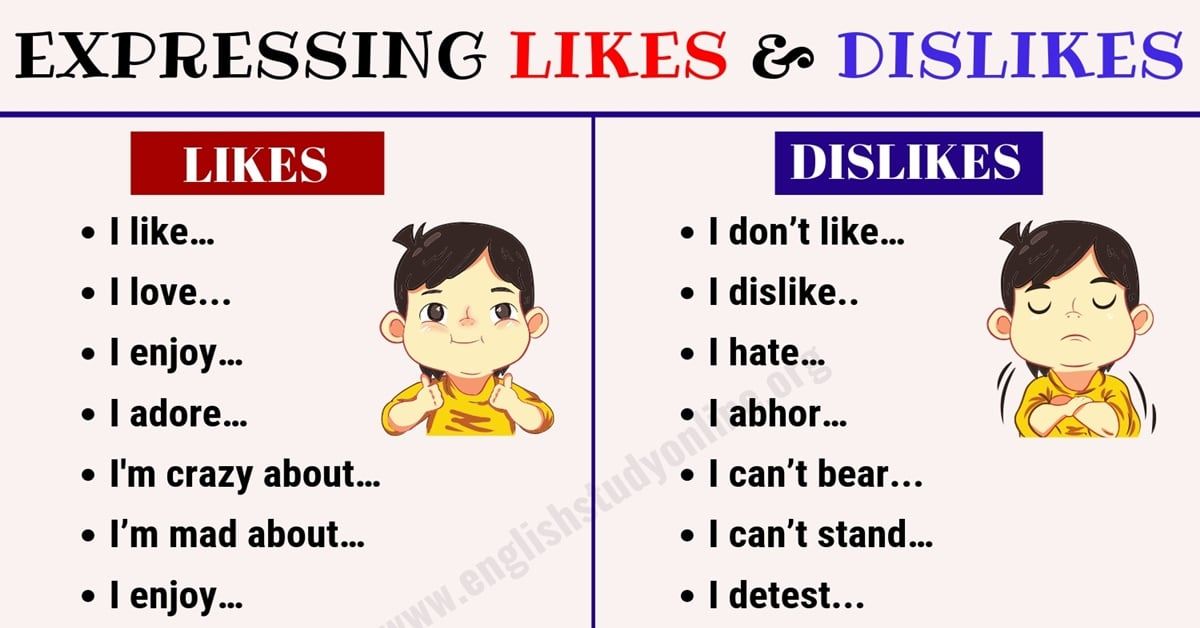

In the following exercise, there are six phrases that a child can say to their parents. Please read each statement and think:

1) What word or words could you describe how the child feels?

2) what phrase would you use to show that you understand his feelings?

Acknowledging a child's feelings

Have you noticed how much thought and effort it takes to show your child that you understand his feelings? Many of us don't think of words like:

“Son, you seem to be angry!”;

or

"This must have been a disappointment for you";

or

“Hmm. You seem to have doubts about whether to go to this party”;

or

"Sounds like you really resent this homework";

or

"Oh, that must have made you very upset!";

or

"When your best friend leaves, it can be very upsetting.

"

Nevertheless, such statements are pleasant for children and help them begin to deal with their own problems. (By the way, don't be afraid to use "difficult" words. The easiest way to learn a new word is to hear it in context.)

You might be thinking, "Okay, in this exercise, I was able to give an answer that showed that I understood feelings child to some extent. But where will the conversation go next? How can I continue it? Would it be okay to give more advice?

Refrain from giving advice. I know how tempting it is to try and solve a child's problem right away:

"Mom, I'm tired."

"Then lie down and rest."

"I'm hungry."

"Well, eat something then."

"I don't want to eat."

"Well, then don't eat."

Resist the temptation to instantly "improve the situation." Instead of giving advice, continue to accept and reflect the child's feelings.

Here is an example of what I mean by this. One father in our group said that his son flew home with a phrase that you were already working on: “I would like to punch this Michael in the nose!” My father said: “Usually the conversation would have gone like this.”

One father in our group said that his son flew home with a phrase that you were already working on: “I would like to punch this Michael in the nose!” My father said: “Usually the conversation would have gone like this.”

Son. I'd like to punch that Michael in the nose!

Father. Why? What's happened?

Son. He threw my notebook into the dirt!

Father. So, did you do anything to him before that?

Son. No!

Father. You are sure?

Son. I swear I never touched it at all.

Father. Michael is your friend. If you follow my advice, you will forget about all this. You are not perfect, you know it. Sometimes you do something and you blame someone else just like you do with your brother.

Son. Not true. He was the first to start ... Why talk to you.

But the father just recently attended a seminar on how to help children deal with their feelings, and this is how the conversation actually unfolded:

Son.

I'd like to punch that Michael in the nose!

Father. Son, you're mad!

Son. I want to stuff his fat muzzle into him!

Father. You are so angry with him!

Son. Do you know what this bully did? At the bus stop, he grabbed my notebook and threw it into the dirt. For no reason!

Father. Hm!

Son. I'm sure he thought I smashed his stupid clay bird in the studio.

Father. You think so?

Son. Yes, he looked at me all the time when he was crying.

Father. Yes?

Son. But I didn't break it. Didn't break!

Father. You know you didn't break.

Son. Well, I didn't do it on purpose! I couldn't do anything because that stupid Debbie pushed me onto the table.

Father. So Debbie pushed you.

Son. Yes. A lot of things fell, but the only thing that broke was the bird. I didn't want to break it. His bird was good.

Father. You really didn't mean to break it.

Son. Yes, but he wouldn't believe me.

Father. Don't you think he'll believe you if you tell him the truth?

Son. I don't know... I'm going to tell him anyway whether he believes me or not. And I think he will have to apologize for throwing my notebook in the dirt!

The father was amazed. He didn't ask questions, and still the child told him the whole story. He did not give advice, and yet the child came up with his own solution. It seemed incredible to him that he had helped his son so much just by listening to him and acknowledging his feelings.

How to talk so kids will listen and how to listen so kids will talk

Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish have been teaching parents and teachers how to communicate with children for over 30 years. With the help of comics, descriptions of real situations and small homework assignments from their books, you can learn how to properly praise, save children from imposed roles, find common ground and much more. The books How to Talk So Kids Will Listen and How to Listen So Kids Will Talk and How to Talk to Kids So They Learn are primarily practical advice from experts.

Parents and teachers need to join forces and form a workable partnership. They need to understand the difference between words that demoralize or inspire confidence, lead to confrontation or encourage interaction, deprive a child of the ability to think and concentrate, or arouse in him a natural desire to learn. Whatever happens at school from 9:00 to 15:00 is largely determined by what happens to the child before and after this time.

What is the problem

When children feel good, they behave well. How do we help them feel good? Accepting their feelings! The problem is that parents usually do not understand the feelings of their children. For example: “You really feel completely different”, “You are saying this because you are tired”, “There is no reason to be so upset.” Constant denial of feelings can confuse and enrage a child. It also teaches them not to understand their feelings and not to trust them.

How to listen to children correctly

When I am upset and offended, the last thing I want to hear is philosophical outpourings, psychological discourse, or other points of view of people. This type of conversation will only make my condition worse.

This type of conversation will only make my condition worse.

To help your child understand his feelings, listen carefully, share his feelings (using the words “yes…”, “hmm”, “understood”), name his feelings and show that you understand the child’s wishes.

If we do not treat children with sympathy, then whatever we say, the child will feel that we are deceiving him or manipulating him. Many of us do not think of such words: "Son, you seem to be angry!" or “Oh, that must have upset you a lot!”

Classic dialogues: "Where are you going?" - "On the street", "What are you doing?" - "Nothing" - did not appear for no reason

One mother said that she does not feel like a good mother if she does not ask her son questions. She was surprised that when she stopped bombarding him with questions and began to listen to what he said to her, he began to open up.

How to talk to children

Refrain from giving your child information he already knows. If you tell a ten-year-old child that milk goes sour if it is not kept in the refrigerator, he may think that you either think he is stupid or sarcastic.

One-word phrase: Teenagers we worked with said that they also preferred one word - "Door", "Dog" or "Utensils" - and found it a pleasant release from the usual teaching. The value of such a statement lies in the fact that instead of an arbitrary order, we give the child the opportunity to show their own initiative and understanding.

Do not use your child's name as such a one-word phrase. When a child hears the disapproving “Susie” many times a day, he begins to associate his name with discontent

It is helpful to share your true feelings with children, they are very good at handling statements such as: “This is not the best time for me to read your essay. I am tense and upset. After dinner, I can give him the attention he deserves."

How to encourage independence

Most parenting books tell us that parents have four main goals, one of them is to separate children from us, to help them become independent individuals who will one day live without our help. We made sure that we should think of our children not as small exact copies or extensions of ourselves, but as one-of-a-kind human beings with a different temperament, different tastes, different feelings, desires and dreams. But how are we supposed to help them become separate, independent individuals? Allowing them to do things for themselves, allowing them to struggle with their own problems, allowing them to learn from their own mistakes.

We made sure that we should think of our children not as small exact copies or extensions of ourselves, but as one-of-a-kind human beings with a different temperament, different tastes, different feelings, desires and dreams. But how are we supposed to help them become separate, independent individuals? Allowing them to do things for themselves, allowing them to struggle with their own problems, allowing them to learn from their own mistakes.

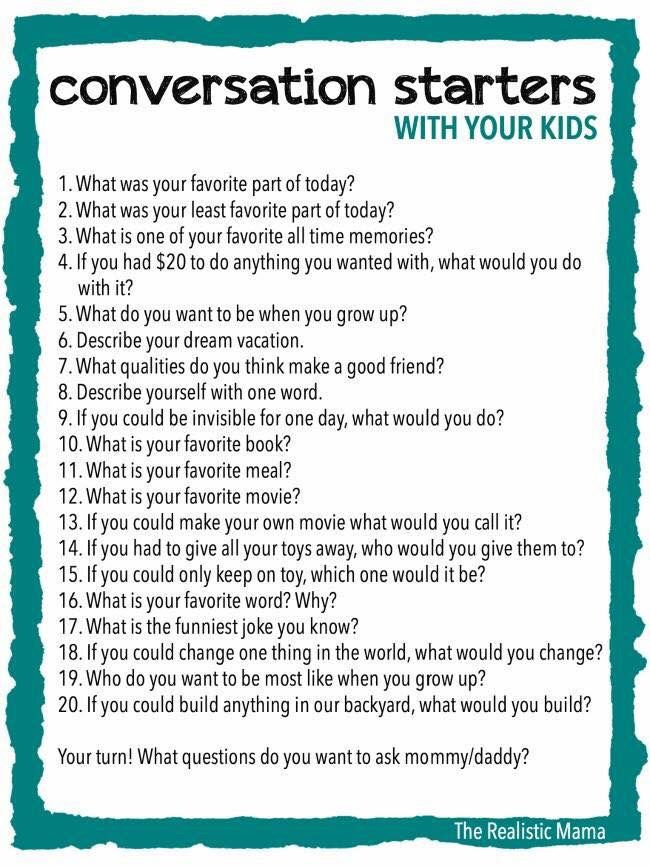

Let the children make a choice (“Do you want to wear gray trousers or red today?”), show respect for the child’s efforts (“The jar can be difficult to open. Sometimes you can pry off the lid with a spoon”). Don't ask too many questions and don't rush to answer questions ("That's an interesting question. What do you think?"). Encourage your child to look for sources of information outside the home (“Perhaps the owner of the pet store has some advice”).

Let children own their own bodies. Refrain from brushing their bangs out of their eyes, straightening their shoulders, brushing off fluff, tucking in their blouse, straightening their collar

"Try it, it's easy" - we don't support the child with this phrase. If he succeeds in something easy, he feels that he has not achieved anything special. And if he fails, he fails at something simple. If we say "this can be difficult", he sets other goals for himself. Avoid phrases like "this might be hard for you".

If he succeeds in something easy, he feels that he has not achieved anything special. And if he fails, he fails at something simple. If we say "this can be difficult", he sets other goals for himself. Avoid phrases like "this might be hard for you".

Some Parent Questions

“I know that feelings need to be accepted, but I’m having a hard time figuring out how to respond to the words ‘You’re mean’ or ‘I hate you’ from my child.”

If these words upset you, you can let your child know: “I didn't like what I just heard. If you are angry about something, tell me in other words. Maybe then I can help you."

"Why not give a child advice when he has a problem?"

When we give a child advice or immediate solutions to his problems, we deprive him of the experience of dealing with his own difficulties. Are there times when you need to give advice? Certainly.

“I must confess that in the past I have told my daughter everything I shouldn't have. Now I'm trying to change the situation, but I have to go through hard times."

Now I'm trying to change the situation, but I have to go through hard times."

A child who has been severely criticized may be hypersensitive. Even a soft "your breakfast" may seem like another accusation of distraction to her. With such a child, you need to ignore a lot. She may view the new parenting approach with suspicion and even hostility, but most people end up responding to it.

Some questions from teachers

“Should I consider my students' feelings? Isn't that the job of a psychologist? I don't have enough time for teaching."

Sometimes what seems to us the longest path turns out to be the most direct and closest. It may be better to spend a few minutes dealing with your student's feelings than to deal with a problem later that will require a lot of valuable study time. In addition, by behaving in this way, you will help a child in a difficult situation.

“When I ask students about their feelings, they don't tell me anything. Why?"

Why?"

Questions like this make children withdraw into themselves. Particularly unpleasant are questions related to why they experience certain feelings. The very word why makes the child evaluate his feelings, look for logical, adults-acceptable reasons for their occurrence. Very often the child simply does not know the reason. When a child is unhappy, he needs a parent or teacher to understand what is happening in his soul: “When you are teased, it hurts a lot. Whatever the reason, it's always unpleasant."

“You say that you need to understand and accept even the worst feelings of children. But won't students interpret this behavior as permission to vent those very feelings?

Not if you can draw a clear line between feelings and behavior. Yes, students have the right to feel anger and express it. No, they have no right to behave in a way that causes other people physical or emotional harm.

“There are two girls in my class who talk all the time. I told them: "You have a choice: either you stop talking, or I will sit you down." They did not stop chatting, and when I seated them, they began to complain about my injustice. What did I do wrong?"

I told them: "You have a choice: either you stop talking, or I will sit you down." They did not stop chatting, and when I seated them, they began to complain about my injustice. What did I do wrong?"

"Your choice" sounded like a threat. Before offering an unpleasant choice, we advise you to recognize the justice of his feelings. You could say something like, "I understand it's hard to sit next to your best friend and not talk to her. After all, you have so much to say to each other. ”And then, by offering a choice, make the students feel that you are on their side. “Well, girls, what do you like better? Sit next to you and control yourself? Or sit at different desks and not be tempted? Discuss this after class, and tomorrow let me know your decision."

"What if a parent comes to a meeting in a hostile or aggressive mood"?

Don't say, "Please calm down. We won't get anywhere if you scream." Instead, acknowledge his right to have such feelings. Make it clear that you understand the strength and nature of his emotions: “I understand how angry you are.