How to make your contractions stronger

Speeding up labour - BabyCentre UK

In this article

- When does active labour start?

- How long is a normal labour?

- What counts as a slow labour?

- Why might my labour be slow?

- How is labour speeded up?

- Can I speed up labour myself?

- What can help me to cope with a long labour?

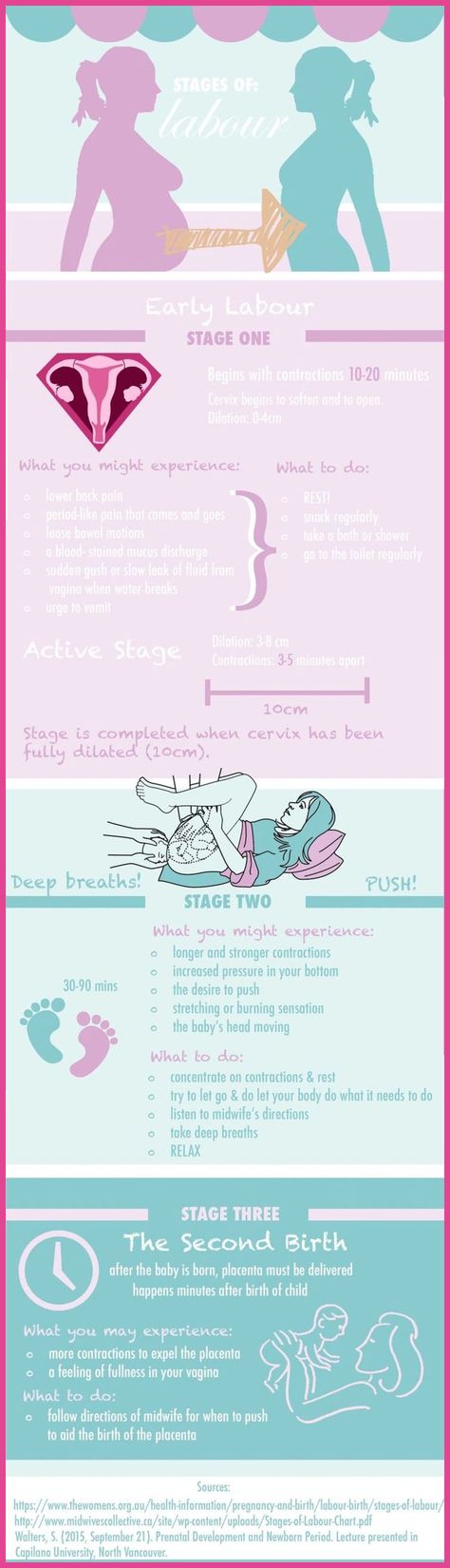

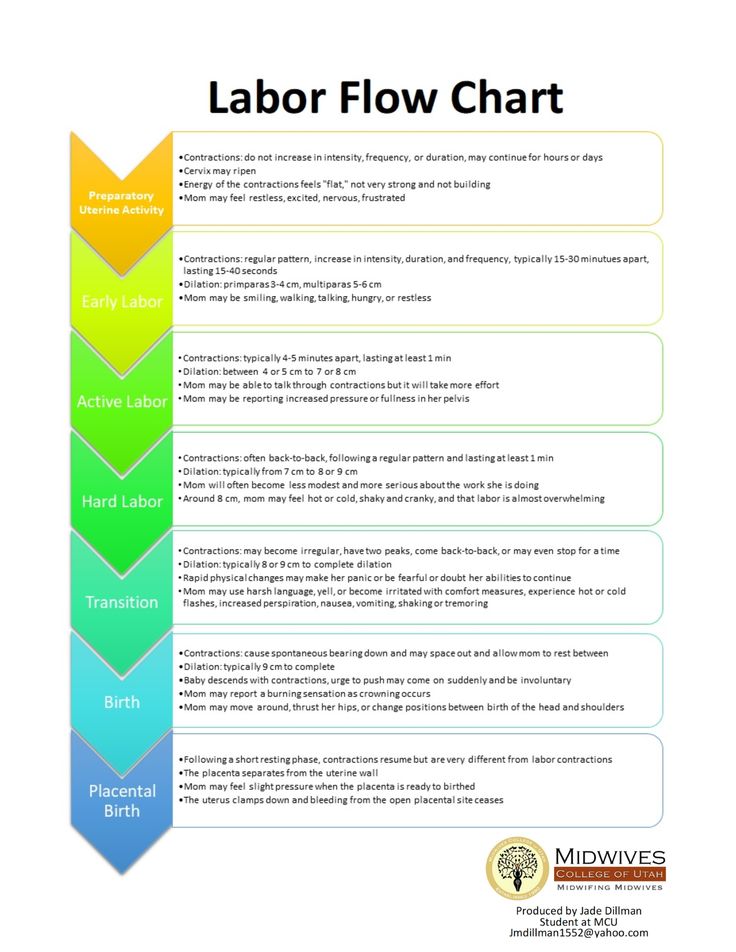

When does active labour start?

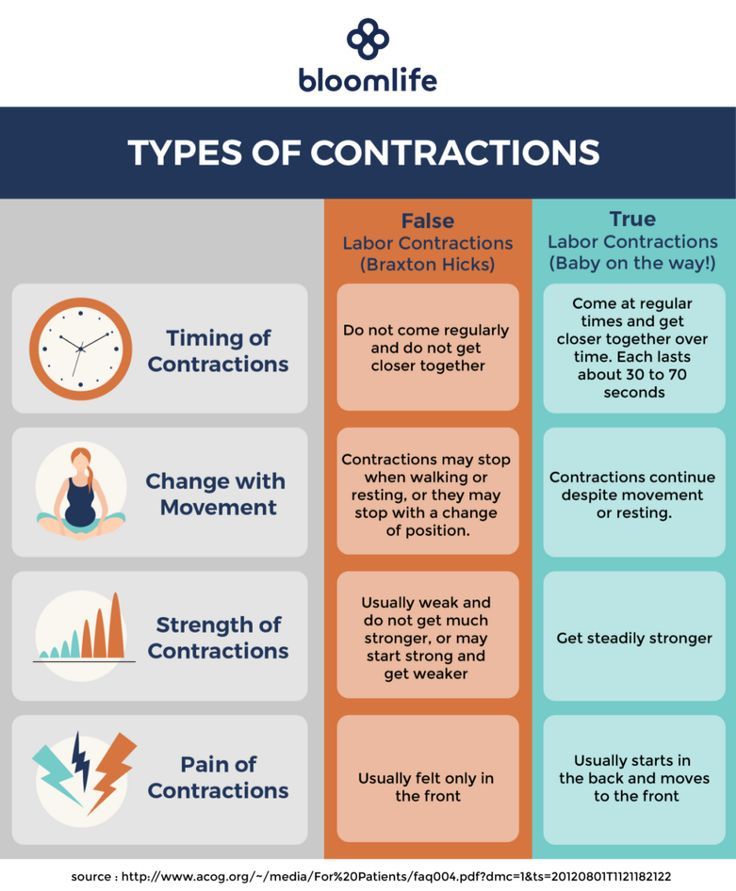

Midwives and doctors say the active first stage of your labour starts when:

- you are having regular, powerful contractions and

- your cervix is dilating from 4cm (1.6in) onwards (NCCWCH 2014).

This may surprise you, as you may start to have strong tightenings well before reaching this point. You may have been awake all night and feeling as though labour has been under way for a while.

Pacing yourself in early labour may help you cope better when active labour gets under way (RCM 2018). Find out how to get through early labour at home.

How long is a normal labour?

Every labour is different, but there are average times that may help to guide you.

Early labour (before it gets active) often lasts about nine hours to 12 hours (Tilden et al 2019). It’s common for it to be longer for first-time mums, lasting 18 hours or more (Ängeby et al 2018).

The active first stage of labour (when your cervix is dilating from 4cm and you are having regular, powerful contractions) for a first baby is usually about eight hours, but it could be shorter or longer (NCCWCH 2014).

If this isn't your first baby, you may have a shorter labour, though this isn't guaranteed. For women who have given birth before, the active first stage of labour lasts, on average, for five hours (NCCWCH 2014). It's unlikely to last for more than 12 hours (NCCWCH 2014).

The pushing phase of labour (active second stage) shouldn't usually take more than three hours, or two hours if you've had a baby before (NCCWCH 2014).

Bear in mind that a quick labour isn't necessarily better either for you or your baby (Rimmer 2014). Very fast labours can be physically and emotionally challenging (Rimmer 2014). However, a very slow labour can leave you exhausted and unwell (Harper et al 2014).

What counts as a slow labour?

During active labour there may be an hour or so of slow or little progress, followed by periods of faster progress (Ehsanipoor and Satin 2019). What matters is how your labour progresses over several hours.

If your labour is straightforward, your midwife will assess your labour every four hours (NCCWCH 2014). With your permission, she'll carry out a vaginal examination to check how open your cervix is (NCCWCH 2014, RCM 2012a, RCN 2016). She'll also listen to your baby's heartbeat using a hand-held Doppler (a Sonicaid) or an ear trumpet (a Pinard stethoscope).

A four-hourly check gives your midwife a good overview of how you're doing. Assessing you more often than that won't necessarily help her to understand more, and can lead to unnecessary intervention in your labour (NCCWCH 2014).

Assessing you more often than that won't necessarily help her to understand more, and can lead to unnecessary intervention in your labour (NCCWCH 2014).

However, if you've had any health concerns during this or a previous pregnancy you may need continuous monitoring.

Your doctor or midwife will also want to monitor you if you've developed complications, such as meconium (your baby’s first poo) in your waters, or fresh bleeding (NCCWCH 2014).

Your midwife will place two electronic sensors on your bump, one to measure contractions and one to measure your baby's heartbeat. The sensors will remain there throughout your labour. Your midwife will still only check your cervix every four hours, though.

If your cervix isn't dilating at a rate of at least 0.5cm (0.2in) an hour over a four-hour period, speeding up your labour may be an option (NCCWCH 2014). This is also called augmentation of labour. Your midwife will discuss whether or not to speed up your labour with you and your doctor.

Each woman's labour is unique. Your wishes should be taken into account, along with what your midwife and doctor recommend is best for you and your baby (Jackson et al 2014, NCCWCH 2014).

Why might my labour be slow?

Some labours are just slow for no particular reason. However, you may have a slow labour if:

- You're dehydrated or exhausted (NCCWCH 2014).

- The position of your baby is making it harder for your labour to progress (NCCWCH 2014).

- You feel particularly scared or anxious. These emotions tend to interfere with the release of the hormone oxytocin, which can help labour along (Aral et al 2014, Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

- Your contractions are infrequent, not very strong, or staying at the same intensity rather than getting stronger (NCCWCH 2014).

- You've had interventions that have slowed your contractions. These could include having to stay still for periods of time, or having an epidural (NCCWCH 2014).

Bear in mind that the first 5cm of cervix dilation nearly always takes much longer than the second 5cm (Ehsanipoor and Satin 2019, Jackson et al 2014, Simkin and Ancheta 2011). Your cervix opens more quickly as your contractions get stronger.

How is labour speeded up?

If your midwife asks whether you'd like to have your labour speeded up, take time to consider your options. If your baby is fine, and your cervix is gradually opening up, even if it's happening slowly, it may be best to leave things alone. You may be perfectly happy to take things gently, staying in tune with your body and your baby.

Or you may be so exhausted that you really want your baby to be born quickly. If that's the case, your midwife can help to move things along in the following ways:

Breaking the waters

Your midwife may suggest breaking your waters to speed up your labour (NCCWCH 2014). This isn't usually recommended near the beginning of labour, as it could increase your risk of infection if labour doesn't start right away (NCCWCH 2008).

This isn't usually recommended near the beginning of labour, as it could increase your risk of infection if labour doesn't start right away (NCCWCH 2008).

However, if the active stage of labour slows right down, breaking your waters can help to get things going again. It may shorten labour by about an hour (NCCWCH 2014).

If you agree to the procedure, here's how your midwife will do it. Once you're on the bed, she'll remove the last section of the bed so that your bottom is right at the end. She may ask you to put your legs up in stirrups, or just hold them apart.

Your midwife will then make a small break in the membranes around your baby. She'll use a long thin probe (amnihook) or a medical glove with a pricked end on one of the fingers (amnicot). She'll scratch the membrane until it bursts and the waters flow out into a tray placed underneath the bed.

This procedure isn't painful but it can be very uncomfortable. You'll probably be glad to get up again once it's over.

Your midwife will then check your baby's heartbeat using a Sonicaid or ear trumpet, to make sure that breaking the waters hasn't distressed him.

Your contractions may become much stronger after your waters have been broken (NCCWCH 2014). Be prepared to work hard with breathing and relaxation exercises. Or you can ask your midwife for some pain relief, such as gas and air, if you need extra help.

Hormone drip

If moving around or breaking your waters doesn't speed up your labour, your doctor may suggest a hormone drip to boost your contractions (NCCWCH 2014). This will contain Syntocinon, which is an artificial form of the labour hormone oxytocin.

If you have Syntocinon, your midwife will continuously monitor your baby's heartbeat by strapping electronic sensors to your tummy (NCCWCH 2014).

Your midwife may also recommend attaching a small clip to your baby's head. The clip is called a fetal scalp electrode and it may provide a more accurate reading than placing a sensor on your tummy. It also allows you to move around more easily.

It also allows you to move around more easily.

Continuous monitoring is recommended because Syntocinon can over-stimulate your womb (uterus) (NCCWCH 2014). You may get very strong, frequent contractions, which could distress your baby.

You're also more likely to need help from pain-relieving drugs to cope with these artificially induced contractions. For this reason, your midwife should offer you an epidural before she starts a Syntocinon drip (NCCWCH 2014).

Can I speed up labour myself?

If you'd prefer not to have your waters broken, or a hormone drip, there are some natural techniques you could try to speed up your labour

- If you're lying on the bed, get up! Being upright and mobile may strengthen your contractions, while also helping you to cope with them (Lawrence et al 2013).

- Take a walk to the toilet. A full bladder may slow down your labour by getting in the way of your baby's head descending (Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

- If you have access to one, get into a warm bath or birth pool. This can reduce your need for an epidural or spinal pain relief (Cluett et al 2018).

- If your baby is lying back-to-back, an experienced midwife may advise you to lie on your side or try kneeling or standing lunge positions. This may help your baby to rotate to a better position for birth (Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

- Have some private time with your partner. Turn the lights down low and have a cuddle, with some nipple stroking or breast massage. This may help your body to release oxytocin, the hormone that strengthens your contractions (Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

You could also try acupuncture during your labour (Mollart et al 2015,Simkin and Ancheta 2011). Complementary therapies probably work best if used throughout labour. You may be able to request an acupuncturist if your labour has slowed down. In some areas of the UK, acupuncturists specialising in childbirth work in teams, meaning that a practitioner is always available.

You can also ask your midwife whether she's certified in any complementary therapies, such as aromatherapy massage, that could help you.

How to help your baby be born

How can you speed up labour and make the birth easier? Discover how to help your baby be born more quickly.More preparing for birth videos

What can help me to cope with a long labour?

These methods may help you:

- Use breathing and relaxation techniques to help you stay calm and focused (NCCWCH 2014). If you've been taking hypnobirthing classes, this is the time to use everything you've learned!

- Ask your birth partner to massage your back, or your feet, if you're sitting in a chair (NCCWCH 2014, Smith et al 2018).

- Listen to your favourite music (NCCWCH 2014).

- Eat and drink when you need to. Have a small snack, such as toast, and water, or an isotonic drink, to stay hydrated (NCCWCH 2014).

- Change your position.

Later in labour you may not feel like walking around, but your midwife can help you to find a comfortable position (NCCWCH 2014).

Later in labour you may not feel like walking around, but your midwife can help you to find a comfortable position (NCCWCH 2014). - Listen to your body and try different positions (Simkin and Ancheta 2011). Move around or adopt positions that feel most comfortable to you as labour progresses (NCCWCH 2014).

- Ask your midwife to explain what's going on. If you feel involved and in control of your labour, you'll probably feel less anxious and more relaxed. This may make your labour easier to cope with, and you may find it a more positive experience (NCCWCH 2014).

- If your midwife is caring for other women as well as you because the unit is busy, continuous support from a student midwife may help your labour to progress. Your birth partner could ask if there's any extra help available (Bolbol-Haghighi et al 2016).

Learn more about what to expect from each stage of labour.

References

Aral I, Koken G, Bozkurt M, et al. 2014. Evaluation of the effects of maternal anxiety on the duration of vaginal labour delivery. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 41(1):32-6

2014. Evaluation of the effects of maternal anxiety on the duration of vaginal labour delivery. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 41(1):32-6

Bolbol-Haghighi N, Masoumi SZ, Kazemi F. 2016. Effect of continued support of midwifery students in labour on the childbirth and labour consequences: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Diagn Res 10(9): QC14–QC17. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed September 2019]

Cluett ER, Burns E, Cuthbert A. 2018. Immersion in water during labour and birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD000111. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Ehsanipoor MD, Satin AJ. 2019. Normal and abnormal labor progression. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com [Accessed September 2019]

Harper LM, Caughey AB, Roehl KA, et al. 2014. Defining an abnormal first stage of labor based on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol (210(6):536.e1-7. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed September 2019]

Jackson K, Marshall JE, Brydon S. 2014. Physiology and care during the first stage of labour. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 327-66

2014. Physiology and care during the first stage of labour. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 327-66

Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. 2013. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD003934. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Mollart LJ, Adam J, Foureur M. 2015. Impact of acupressure on onset of labour and labour duration: a systematic review. Women Birth 28(3): 199-206

NCCWCH. 2014. Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, Clinical guideline, 190. www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

RCM. 2012a. Assessing progress in labour. Royal College of Midwives Trust, Evidence based guidelines for midwifery-led care in labour

RCM. 2012b. Rupturing membranes. Royal College of Midwives Trust, Evidence based guidelines for midwifery-led care in labour

RCM. 2018. Midwifery care in labour guidance for all women in all settings. Royal College of Midwives, Midwifery Blue Top Guidance

2018. Midwifery care in labour guidance for all women in all settings. Royal College of Midwives, Midwifery Blue Top Guidance

RCN. 2016. Genital examination in women. Royal College of Nursing. www.rcn.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

Rimmer A. 2014. Prolonged pregnancy and disorders of uterine action. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles textbook for midwives 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 417-33

Simkin P, Ancheta R. 2011. The labor progress handbook: early interventions to prevent and treat dystocia. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell

Smith CA, Levett KM, Collins CT, et al. 2018. Massage, reflexology and other manual methods for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD009290. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Smyth RMD, Markham C, Dowswell T. 2013. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006167. www. cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Thakar R, Sultan AH. 2014. The female pelvis and the reproductive organs. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 55-80

Show references Hide references

Speeding up labour - BabyCentre UK

In this article

- When does active labour start?

- How long is a normal labour?

- What counts as a slow labour?

- Why might my labour be slow?

- How is labour speeded up?

- Can I speed up labour myself?

- What can help me to cope with a long labour?

When does active labour start?

Midwives and doctors say the active first stage of your labour starts when:

- you are having regular, powerful contractions and

- your cervix is dilating from 4cm (1.6in) onwards (NCCWCH 2014).

This may surprise you, as you may start to have strong tightenings well before reaching this point. You may have been awake all night and feeling as though labour has been under way for a while.

You may have been awake all night and feeling as though labour has been under way for a while.

Pacing yourself in early labour may help you cope better when active labour gets under way (RCM 2018). Find out how to get through early labour at home.

How long is a normal labour?

Every labour is different, but there are average times that may help to guide you.

Early labour (before it gets active) often lasts about nine hours to 12 hours (Tilden et al 2019). It’s common for it to be longer for first-time mums, lasting 18 hours or more (Ängeby et al 2018).

The active first stage of labour (when your cervix is dilating from 4cm and you are having regular, powerful contractions) for a first baby is usually about eight hours, but it could be shorter or longer (NCCWCH 2014).

If this isn't your first baby, you may have a shorter labour, though this isn't guaranteed. For women who have given birth before, the active first stage of labour lasts, on average, for five hours (NCCWCH 2014). It's unlikely to last for more than 12 hours (NCCWCH 2014).

It's unlikely to last for more than 12 hours (NCCWCH 2014).

The pushing phase of labour (active second stage) shouldn't usually take more than three hours, or two hours if you've had a baby before (NCCWCH 2014).

Bear in mind that a quick labour isn't necessarily better either for you or your baby (Rimmer 2014). Very fast labours can be physically and emotionally challenging (Rimmer 2014). However, a very slow labour can leave you exhausted and unwell (Harper et al 2014).

What counts as a slow labour?

During active labour there may be an hour or so of slow or little progress, followed by periods of faster progress (Ehsanipoor and Satin 2019). What matters is how your labour progresses over several hours.

If your labour is straightforward, your midwife will assess your labour every four hours (NCCWCH 2014). With your permission, she'll carry out a vaginal examination to check how open your cervix is (NCCWCH 2014, RCM 2012a, RCN 2016). She'll also listen to your baby's heartbeat using a hand-held Doppler (a Sonicaid) or an ear trumpet (a Pinard stethoscope).

She'll also listen to your baby's heartbeat using a hand-held Doppler (a Sonicaid) or an ear trumpet (a Pinard stethoscope).

A four-hourly check gives your midwife a good overview of how you're doing. Assessing you more often than that won't necessarily help her to understand more, and can lead to unnecessary intervention in your labour (NCCWCH 2014).

However, if you've had any health concerns during this or a previous pregnancy you may need continuous monitoring.

Your doctor or midwife will also want to monitor you if you've developed complications, such as meconium (your baby’s first poo) in your waters, or fresh bleeding (NCCWCH 2014).

Your midwife will place two electronic sensors on your bump, one to measure contractions and one to measure your baby's heartbeat. The sensors will remain there throughout your labour. Your midwife will still only check your cervix every four hours, though.

If your cervix isn't dilating at a rate of at least 0.5cm (0. 2in) an hour over a four-hour period, speeding up your labour may be an option (NCCWCH 2014). This is also called augmentation of labour. Your midwife will discuss whether or not to speed up your labour with you and your doctor.

2in) an hour over a four-hour period, speeding up your labour may be an option (NCCWCH 2014). This is also called augmentation of labour. Your midwife will discuss whether or not to speed up your labour with you and your doctor.

Each woman's labour is unique. Your wishes should be taken into account, along with what your midwife and doctor recommend is best for you and your baby (Jackson et al 2014, NCCWCH 2014).

Why might my labour be slow?

Some labours are just slow for no particular reason. However, you may have a slow labour if:

- You're dehydrated or exhausted (NCCWCH 2014).

- The position of your baby is making it harder for your labour to progress (NCCWCH 2014).

- You feel particularly scared or anxious. These emotions tend to interfere with the release of the hormone oxytocin, which can help labour along (Aral et al 2014, Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

- Your contractions are infrequent, not very strong, or staying at the same intensity rather than getting stronger (NCCWCH 2014).

- You've had interventions that have slowed your contractions. These could include having to stay still for periods of time, or having an epidural (NCCWCH 2014).

Bear in mind that the first 5cm of cervix dilation nearly always takes much longer than the second 5cm (Ehsanipoor and Satin 2019, Jackson et al 2014, Simkin and Ancheta 2011). Your cervix opens more quickly as your contractions get stronger.

How is labour speeded up?

If your midwife asks whether you'd like to have your labour speeded up, take time to consider your options. If your baby is fine, and your cervix is gradually opening up, even if it's happening slowly, it may be best to leave things alone. You may be perfectly happy to take things gently, staying in tune with your body and your baby.

Or you may be so exhausted that you really want your baby to be born quickly. If that's the case, your midwife can help to move things along in the following ways:

Breaking the waters

Your midwife may suggest breaking your waters to speed up your labour (NCCWCH 2014). This isn't usually recommended near the beginning of labour, as it could increase your risk of infection if labour doesn't start right away (NCCWCH 2008).

This isn't usually recommended near the beginning of labour, as it could increase your risk of infection if labour doesn't start right away (NCCWCH 2008).

However, if the active stage of labour slows right down, breaking your waters can help to get things going again. It may shorten labour by about an hour (NCCWCH 2014).

If you agree to the procedure, here's how your midwife will do it. Once you're on the bed, she'll remove the last section of the bed so that your bottom is right at the end. She may ask you to put your legs up in stirrups, or just hold them apart.

Your midwife will then make a small break in the membranes around your baby. She'll use a long thin probe (amnihook) or a medical glove with a pricked end on one of the fingers (amnicot). She'll scratch the membrane until it bursts and the waters flow out into a tray placed underneath the bed.

This procedure isn't painful but it can be very uncomfortable. You'll probably be glad to get up again once it's over.

Your midwife will then check your baby's heartbeat using a Sonicaid or ear trumpet, to make sure that breaking the waters hasn't distressed him.

Your contractions may become much stronger after your waters have been broken (NCCWCH 2014). Be prepared to work hard with breathing and relaxation exercises. Or you can ask your midwife for some pain relief, such as gas and air, if you need extra help.

Hormone drip

If moving around or breaking your waters doesn't speed up your labour, your doctor may suggest a hormone drip to boost your contractions (NCCWCH 2014). This will contain Syntocinon, which is an artificial form of the labour hormone oxytocin.

If you have Syntocinon, your midwife will continuously monitor your baby's heartbeat by strapping electronic sensors to your tummy (NCCWCH 2014).

Your midwife may also recommend attaching a small clip to your baby's head. The clip is called a fetal scalp electrode and it may provide a more accurate reading than placing a sensor on your tummy. It also allows you to move around more easily.

It also allows you to move around more easily.

Continuous monitoring is recommended because Syntocinon can over-stimulate your womb (uterus) (NCCWCH 2014). You may get very strong, frequent contractions, which could distress your baby.

You're also more likely to need help from pain-relieving drugs to cope with these artificially induced contractions. For this reason, your midwife should offer you an epidural before she starts a Syntocinon drip (NCCWCH 2014).

Can I speed up labour myself?

If you'd prefer not to have your waters broken, or a hormone drip, there are some natural techniques you could try to speed up your labour

- If you're lying on the bed, get up! Being upright and mobile may strengthen your contractions, while also helping you to cope with them (Lawrence et al 2013).

- Take a walk to the toilet. A full bladder may slow down your labour by getting in the way of your baby's head descending (Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

- If you have access to one, get into a warm bath or birth pool. This can reduce your need for an epidural or spinal pain relief (Cluett et al 2018).

- If your baby is lying back-to-back, an experienced midwife may advise you to lie on your side or try kneeling or standing lunge positions. This may help your baby to rotate to a better position for birth (Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

- Have some private time with your partner. Turn the lights down low and have a cuddle, with some nipple stroking or breast massage. This may help your body to release oxytocin, the hormone that strengthens your contractions (Simkin and Ancheta 2011).

You could also try acupuncture during your labour (Mollart et al 2015,Simkin and Ancheta 2011). Complementary therapies probably work best if used throughout labour. You may be able to request an acupuncturist if your labour has slowed down. In some areas of the UK, acupuncturists specialising in childbirth work in teams, meaning that a practitioner is always available.

You can also ask your midwife whether she's certified in any complementary therapies, such as aromatherapy massage, that could help you.

How to help your baby be born

How can you speed up labour and make the birth easier? Discover how to help your baby be born more quickly.More preparing for birth videos

What can help me to cope with a long labour?

These methods may help you:

- Use breathing and relaxation techniques to help you stay calm and focused (NCCWCH 2014). If you've been taking hypnobirthing classes, this is the time to use everything you've learned!

- Ask your birth partner to massage your back, or your feet, if you're sitting in a chair (NCCWCH 2014, Smith et al 2018).

- Listen to your favourite music (NCCWCH 2014).

- Eat and drink when you need to. Have a small snack, such as toast, and water, or an isotonic drink, to stay hydrated (NCCWCH 2014).

- Change your position.

Later in labour you may not feel like walking around, but your midwife can help you to find a comfortable position (NCCWCH 2014).

Later in labour you may not feel like walking around, but your midwife can help you to find a comfortable position (NCCWCH 2014). - Listen to your body and try different positions (Simkin and Ancheta 2011). Move around or adopt positions that feel most comfortable to you as labour progresses (NCCWCH 2014).

- Ask your midwife to explain what's going on. If you feel involved and in control of your labour, you'll probably feel less anxious and more relaxed. This may make your labour easier to cope with, and you may find it a more positive experience (NCCWCH 2014).

- If your midwife is caring for other women as well as you because the unit is busy, continuous support from a student midwife may help your labour to progress. Your birth partner could ask if there's any extra help available (Bolbol-Haghighi et al 2016).

Learn more about what to expect from each stage of labour.

References

Aral I, Koken G, Bozkurt M, et al. 2014. Evaluation of the effects of maternal anxiety on the duration of vaginal labour delivery. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 41(1):32-6

2014. Evaluation of the effects of maternal anxiety on the duration of vaginal labour delivery. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 41(1):32-6

Bolbol-Haghighi N, Masoumi SZ, Kazemi F. 2016. Effect of continued support of midwifery students in labour on the childbirth and labour consequences: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Diagn Res 10(9): QC14–QC17. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed September 2019]

Cluett ER, Burns E, Cuthbert A. 2018. Immersion in water during labour and birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD000111. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Ehsanipoor MD, Satin AJ. 2019. Normal and abnormal labor progression. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com [Accessed September 2019]

Harper LM, Caughey AB, Roehl KA, et al. 2014. Defining an abnormal first stage of labor based on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol (210(6):536.e1-7. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [Accessed September 2019]

Jackson K, Marshall JE, Brydon S. 2014. Physiology and care during the first stage of labour. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 327-66

2014. Physiology and care during the first stage of labour. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 327-66

Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. 2013. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD003934. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Mollart LJ, Adam J, Foureur M. 2015. Impact of acupressure on onset of labour and labour duration: a systematic review. Women Birth 28(3): 199-206

NCCWCH. 2014. Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, Clinical guideline, 190. www.nice.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

RCM. 2012a. Assessing progress in labour. Royal College of Midwives Trust, Evidence based guidelines for midwifery-led care in labour

RCM. 2012b. Rupturing membranes. Royal College of Midwives Trust, Evidence based guidelines for midwifery-led care in labour

RCM. 2018. Midwifery care in labour guidance for all women in all settings. Royal College of Midwives, Midwifery Blue Top Guidance

2018. Midwifery care in labour guidance for all women in all settings. Royal College of Midwives, Midwifery Blue Top Guidance

RCN. 2016. Genital examination in women. Royal College of Nursing. www.rcn.org.uk [Accessed September 2019]

Rimmer A. 2014. Prolonged pregnancy and disorders of uterine action. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles textbook for midwives 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 417-33

Simkin P, Ancheta R. 2011. The labor progress handbook: early interventions to prevent and treat dystocia. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell

Smith CA, Levett KM, Collins CT, et al. 2018. Massage, reflexology and other manual methods for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD009290. www.cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Smyth RMD, Markham C, Dowswell T. 2013. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006167. www. cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

cochranelibrary.com [Accessed September 2019]

Thakar R, Sultan AH. 2014. The female pelvis and the reproductive organs. In: Marshall JE, Raynor MD. eds. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 16th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 55-80

Show references Hide references

How to behave in childbirth? Learning to give birth quickly and with problems

Childbirth is a natural process, laid down by nature. The whole sequence of events that take place during this period is predetermined, but by your actions you can either speed up the birth of a baby, or complicate his birth.

Childbirth is the final and most important stage of pregnancy. How you behave and how accurately and skillfully you follow the instructions of the obstetrician depends on how you will feel and how quickly your baby will be born. What does a newborn need to know? Let's try to answer the most important questions. nine0003

1. When is it time to go to the maternity hospital?

Childbirth is a natural result of hormonal changes that occur in your body during the final stages of pregnancy. The sagging belly and heaviness in its lower part and the lumbar region speak of the imminent denouement of the story. Periodically, weak contractions occur, the stomach tenses and pulls down, but these sensations quickly pass, the uterus relaxes again and becomes soft. Such contractions are harbingers of childbirth, but they are far from real labor activity. nine0003

The sagging belly and heaviness in its lower part and the lumbar region speak of the imminent denouement of the story. Periodically, weak contractions occur, the stomach tenses and pulls down, but these sensations quickly pass, the uterus relaxes again and becomes soft. Such contractions are harbingers of childbirth, but they are far from real labor activity. nine0003

The signal to call an ambulance should be sufficiently strong contractions that are repeated at regular intervals, the appearance of mucous secretions from the genital tract, slightly stained with blood, or the outflow of amniotic fluid.

2. First stage of childbirth: we breathe for two!

From the moment the contractions become regular, the first stage of labor begins, during which the strength, frequency and duration of uterine spasms increases and the cervix opens. nine0003

During spastic contraction of the uterine muscle fibers, the blood vessels that carry arterial blood to the placenta and fetus are compressed. The fetus begins to experience a lack of oxygen, and this involuntarily makes you breathe deeper. The reflex increase in the rate of contractions of your heart will ensure the delivery of oxygen to the child. Nature has provided that these processes take place regardless of your consciousness, but you should not completely rely on it.

The fetus begins to experience a lack of oxygen, and this involuntarily makes you breathe deeper. The reflex increase in the rate of contractions of your heart will ensure the delivery of oxygen to the child. Nature has provided that these processes take place regardless of your consciousness, but you should not completely rely on it.

In the first stage of labor, during each contraction, you need to breathe calmly and deeply, trying not to hold your breath while inhaling. At the same time, the air should fill the upper sections of the lungs, as if raising the chest. You need to inhale through the nose, slowly and smoothly, exhale through the mouth, just as evenly. nine0003

3. Auto-training in the prenatal ward

To speed up the opening of the cervix, you need to walk more, but sitting is not recommended, while blood flow in the limbs is disturbed and venous blood stagnation occurs in the pelvis. From time to time it is useful to lie on your side, stroking your lower abdomen with both hands in the direction from the center to the sides, focusing on breathing and saying to yourself: "I am calm, I am in control of the situation, each contraction brings me closer to the birth of a baby. "

"

4. To relieve pain

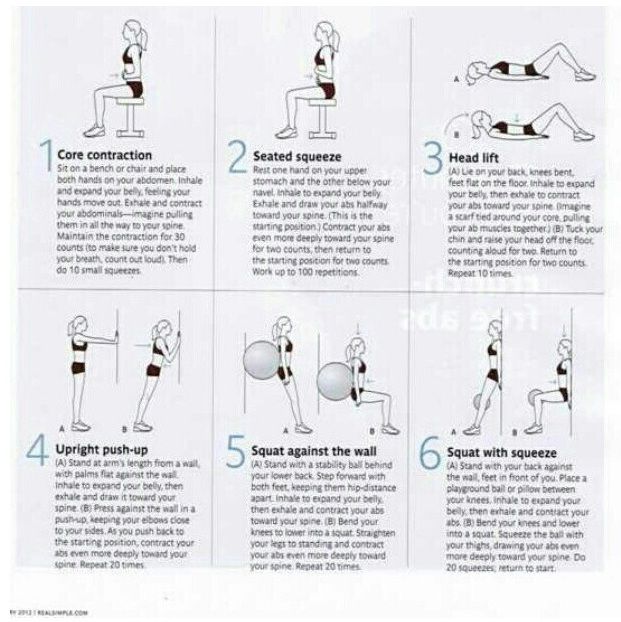

Acupressure of the lower back can help relieve pain. Find the outer corners of the sacral rhombus on your lower back and massage these points with clenched fists.

Monitor the frequency and duration of contractions and if they weaken or sharply increase, immediately inform your doctor. In case of severe pain, you can ask for an anesthetic, but you should remember that you should not take the medicine too often, this is fraught with narcotic depression of the newborn and a decrease in his adaptive abilities. nine0003

If dilatation of the cervix causes reflex vomiting, rinse the mouth with water and then drink a few sips to replace the lost fluid. Do not drink a lot, this can provoke a recurrence of vomiting.

5. The maternity ward is not a place for tantrums

They say that difficult childbirth is a person's retribution for walking upright. Childbirth is actually a painful process, but the presence of reason allows us, representatives of the genus Homo sapiens, to control our emotions. Screaming, crying, tantrums and swearing have no place in the maternity ward. This creates a tense environment, interferes with the normal course of childbirth, complicates diagnostic and therapeutic measures, and ultimately affects their outcome. nine0003

Screaming, crying, tantrums and swearing have no place in the maternity ward. This creates a tense environment, interferes with the normal course of childbirth, complicates diagnostic and therapeutic measures, and ultimately affects their outcome. nine0003

6. Second stage of labor - pushing and expulsion of the fetus

After the baby's head slips through the dilated cervix and finds itself on the bottom of the pelvis, the pushing period of labor begins. At this time, there is a desire to push, as it usually happens during a bowel movement, but at the same time many times stronger. At first, the attempts are controllable, they can be "breathed", but by the beginning of the third stage of labor, the expulsion of the fetus, they become unbearable.

With the beginning of the straining period, you will be transferred to the delivery room. Having settled down on the delivery table, rest your feet on the special steps, firmly grasp the handrails and wait for the midwife's command. nine0003

nine0003

While pushing, inhale deeply, close your mouth, clench your lips tightly, pull the handrails of the delivery table towards you and direct all the exhalation energy down, squeezing the fetus out of you. When the top of the baby appears from the genital slit, the midwife will ask you to ease your efforts. With gentle movements of her hands, she will first release the baby’s forehead, then his face and chin, after which she will ask you to push again. At the moment of the next attempt, the baby's shoulders and torso will be born. After the newborn is born, you can breathe freely and rest a little, but the birth is not over. nine0003

7. Third stage of labor and final

Third stage of labor - afterbirth. At this time, weak contractions are observed, due to which the fetal membranes gradually exfoliate from the walls of the uterus.

About 10 minutes after your baby is born, your midwife will ask you to push again to deliver your afterbirth. The doctor will carefully examine it and make sure that all parts of the membranes have come out. After that, with the help of mirrors, he will examine the cervix and make sure that it is intact. If necessary, all tears will be closed with absorbable sutures. nine0003

The doctor will carefully examine it and make sure that all parts of the membranes have come out. After that, with the help of mirrors, he will examine the cervix and make sure that it is intact. If necessary, all tears will be closed with absorbable sutures. nine0003

You will have to spend another couple of hours in the delivery room with an ice-filled bladder on your stomach. To quickly contract the uterus, you will be given injections of special drugs. When the threat of postpartum hemorrhage has passed, you will be transferred to the postpartum ward to the baby.

Childbirth completed. Ahead of the postpartum period, during which your body will recover after pregnancy.

More details on Medkrug.RU: http://www.medkrug.ru/article/show/kak_pravilno_vesti_sebja_v_rodah_uchimsja_rozhat_bystro_i_problem

Vovk Lyudmila Anatolyevna

Reproductologist, Obstetrician-gynecologist

Lapino-1 Clinical Hospital "Mother and Child"

We walk and dance

If earlier in the maternity hospital, with the onset of labor, a woman was put to bed, now, on the contrary, obstetricians recommend that the expectant mother move . For example, you can just walk: the rhythm of steps soothes, and gravity helps the neck to open faster. You need to walk as fast as it is convenient, without sprinting up the stairs, it’s better to just “cut circles” along the corridor or ward, from time to time (during the aggravation of the fight) resting on something. The gait does not matter - you can roll over like a duck, rotate your hips, walk with your legs wide apart. It is worth trying and dancing, even if you think that you do not know how. For example, you can swing your hips back and forth, describe circles and figure eights with your fifth point, sway in a knee-elbow position. The main thing is to move smoothly and slowly, without sudden movements. nine0003

For example, you can just walk: the rhythm of steps soothes, and gravity helps the neck to open faster. You need to walk as fast as it is convenient, without sprinting up the stairs, it’s better to just “cut circles” along the corridor or ward, from time to time (during the aggravation of the fight) resting on something. The gait does not matter - you can roll over like a duck, rotate your hips, walk with your legs wide apart. It is worth trying and dancing, even if you think that you do not know how. For example, you can swing your hips back and forth, describe circles and figure eights with your fifth point, sway in a knee-elbow position. The main thing is to move smoothly and slowly, without sudden movements. nine0003

Showering and bathing

For many people, water is a great way to relieve fatigue and tension, and it also helps with painful contractions. You can just stand in the shower, or you can lie down in the bath. Warm water will warm the muscles of the back and abdomen, they will relax, and the birth canal will relax - as a result, the pain may decrease. Well, if it does not decrease, then in any case, the water will relieve stress and at least for a while distract from the pain. So if there is a shower or jacuzzi bath in the delivery room, do not be shy and try this method of pain relief for contractions. The only thing is that the water should not be too hot, even if it seems that heat helps to better endure contractions. nine0003

Well, if it does not decrease, then in any case, the water will relieve stress and at least for a while distract from the pain. So if there is a shower or jacuzzi bath in the delivery room, do not be shy and try this method of pain relief for contractions. The only thing is that the water should not be too hot, even if it seems that heat helps to better endure contractions. nine0003

Swinging on the ball

Until recently, fitball (rubber inflatable ball) in the rodblock was something outlandish, and today is found in many maternity hospitals. And if you find a fitball in your rodblock, be sure to use it. You can sit on the ball astride and swing, rotate the pelvis, spring, roll from side to side. You can also kneel down, lean on the ball with your hands and chest and sway back and forth. All these movements on the ball will relax the muscles, increase the mobility of the pelvic bones, improve the opening of the neck, and reduce the pain of contractions. And while the woman is sitting on the ball, her partner (usually her husband) can massage her neck area for additional relaxation. nine0003

And while the woman is sitting on the ball, her partner (usually her husband) can massage her neck area for additional relaxation. nine0003

To be more comfortable, the ball should be soft, slightly deflated, and large, with a diameter of at least 75 cm.

Hanging on a rope or wall bar

When the contractions become very strong and painful, you can take postures in which the stomach is, as it were, in a “suspended” state. Some advanced maternity hospitals have wall bars and ropes attached to the ceiling for this. During contraction, you can hang on them, as a result, the weight of the uterus will put less pressure on large blood vessels, and this will improve uteroplacental blood flow. In addition, in the “suspended” position, the load from the spine will be removed, which will also reduce pain. nine0003

Do not hang on a rope or a wall only if there is a desire to push, and the cervix has not yet opened and the efforts must be restrained.

Lying comfortably

If a woman in childbirth wants not to move, but, on the contrary, to lie down, then, of course, she can lie down. In modern maternity hospitals, instead of traditional ones, there are transforming beds: you can change their height, lower or raise the headboard or foot end, adjust the tilt level, push or push some part of the bed. There are also handrails in transforming beds (to use them to rest or even hang on them), and leg supports, and retractable pillows, and special backs - in general, everything in order to fit the bed under you and take it with it comfortable position. Moreover, this can be done without any physical effort - using the remote control. nine0003

In modern maternity hospitals, instead of traditional ones, there are transforming beds: you can change their height, lower or raise the headboard or foot end, adjust the tilt level, push or push some part of the bed. There are also handrails in transforming beds (to use them to rest or even hang on them), and leg supports, and retractable pillows, and special backs - in general, everything in order to fit the bed under you and take it with it comfortable position. Moreover, this can be done without any physical effort - using the remote control. nine0003

We use everything we have

In any roadblock, even if it is minimally equipped, you can still find something useful. For example, if during a fight you want to take a position with a support, you can lean forward and rest against something that turns up under your arm - a table, a headboard, a window sill. The main thing is that the support must be very stable. You can also get on all fours in the “cat pose” and focus on your hands, and to make it more convenient, put a pillow and a folded blanket under your chest.