How to know if child is transgender

How to know if your child is transgender, according to an expert

It's a troubling fact: Anti-transgender parents can damage their children — potentially for life. A lot of research shows that if parents or families reject, mistreat, or otherwise mishandle a child due to the child's gender identity, they can significantly increase the risks of the child acting out, developing mental health issues, and attempting suicide. So how can a parent make sure that they get this right?

I reached out to Diane Ehrensaft, a developmental psychologist who works closely with trans kids and author of the insightful The Gender Creative Child, to get answers to some of the questions parents might have.

In short, Ehrensaft put forward a very consistent theme: Parents should pay very close attention to persistent cues from their children, take those cues seriously, and not try to forcefully alter the direction a child seems to be going in. So if a child is consistently showing signs that their gender identity or expression does not match the gender that was assigned to them at birth, parents should take that seriously, and let the child live based on their clearly and persistently expressed identity. And to the extent a parent can get this wrong, it's by acting too rigidly and trying to force a child into acting like someone they're simply not.

What follows is my conversation with Ehrensaft, edited for length and clarity.

How to tell if a child is transgender: pay attention, and take the cues seriously — without policing gender

Samuel Kubani/AFP via Getty ImagesGerman Lopez: How can parents realize if their child is transgender?

Diane Ehrensaft: Like other parts of parenting, keep your eyes open and listen. Kids will send out pretty strong smoke signals that they're working out something about gender. The parents may not be able to know that the child is transgender right away.

Unfortunately, we don't have a blood test, which everybody wishes we did to be crystal clear. We can only get a cross-section of a child and where that child is at the moment.

Here's what we look for:

If a child says something like the statement, "you have it wrong; I'm not the gender you think I am" or "why did God get it wrong?" or "can I go back in your tummy and come out with the right parts?" you want to pay attention to those signals.

If a child is insistent, consistent, and persistent on that message or related messages, we want to pay attention to it. So it's not just one point in time, but over many points in time. It keeps coming back to the same thing.

"If a child says something like … 'Can I go back in your tummy and come out with the right parts?' you want to pay attention to those signals"

If a child, particularly a young child, is really excited about their body parts, and says "Can I grow one?" or "Can I cut this one off?" there's often a signal of a real unhappiness with the body that you have and that marks you as a boy or a girl in the culture.

Lots of kids these days like to play with toys that were labeled for the other gender. That's not uncommon. We know Target took down gender-segregated toys. We know something's going on in the culture. So there's a lot of kids — boys who want to play with dolls, girls who want to play with trucks, etc.

The child who's transgender often will go beyond play to what I call "serious business. " They're not just, for example, wanting to try out their sister's princess dress and pretend to be a princess for a day. They do that, too. But they may — as someone who's [designated as] a boy who says, "I'm a girl" — go and steal their sister's full clothes, regular girl clothes, so they can dress to tell people, "Hey, this is who I am. I'm not a fairy princess. But I'm a girl who wants to go to school dressed like this." So you look for play as "serious business."

" They're not just, for example, wanting to try out their sister's princess dress and pretend to be a princess for a day. They do that, too. But they may — as someone who's [designated as] a boy who says, "I'm a girl" — go and steal their sister's full clothes, regular girl clothes, so they can dress to tell people, "Hey, this is who I am. I'm not a fairy princess. But I'm a girl who wants to go to school dressed like this." So you look for play as "serious business."

It's not fool-proof, but those are good signs.

There are things parents should do if they realize a child is transgender. But mostly, they should be accepting.

ShutterstockGL: Let's say some parents think their child is trans. What should they do then?

DE: In terms of the mental health field, I will quote Dickens: It's the best of times, it's the worst of times.

If they can find a well-trained, gender-affirmative professional to help them think about it, that's a good way to go, because it's hard to do this on your own. Some people do it with support groups. Some people do it by connecting with other people online. Some people just have it within their own bones to be able to read the tea leaves and know what to do about it.

Some people do it with support groups. Some people do it by connecting with other people online. Some people just have it within their own bones to be able to read the tea leaves and know what to do about it.

But given the journey ahead, if you can find someone like a pediatrician that you go to from time to time for check-ups, but who's a mental health professional, sensitive to gender issues, [and] who can just be part of your team to think about it and offer their expertise, that's a good step.

"If they can find a well-trained, gender-affirmative professional to help them think about it, that's a good way to go"

What a parent can do is to watch out for being a police officer of gender. That harms kids, and it gives them bad messages. So if you say, "You can't do that, because boys aren't allowed to," that's a real pain on your child, and that can have some damaging effects.

If you say something a little different — "You know, honey, where we live people don't understand this, so we might do this just at home, but until we help the people out there to understand it, we might just leave it at home" — it's still a bit of a mixed message, but it says to the child that "the problem is not with you, the problem is the town we live in, so we're going to create safe spaces for you. " The hope there is the child doesn't take it in as "I'm weird" but that this world has a lot of learning to do.

" The hope there is the child doesn't take it in as "I'm weird" but that this world has a lot of learning to do.

But the first thing you want to do, like with any other sense of identity, is instill pride in the child, rather than shame.

Javier Zarracina/VoxGL: I imagine that a lot of parents are unfortunately not going to have access to very good mental health professionals for all sorts of reasons — geography, insurance, or whatnot. So what are some of the common tips and guidance you would give to those parents, who think their kids are trans?

DE: The first thing — and this is the motto you can put on your wall — is around children's gender, it's not for us to say, but for them to tell, and to give them the opportunity to say what's going on with them. And listen.

The second is that all of us, as parents and people walking down the street, have what I call gender ghosts and gender angels.

The gender ghosts are all of the messages that we got in the way we live — such as our religious beliefs — that tell us that there's something wrong if a child is either gender nonconforming or transgender, or that makes you feel uncomfortable or weird about it. You can't sweep the gender ghost under the rug, because they're there. So you have to take them out and take a look at them. And if you're parents, you always should be questioning yourselves: "Are any of these beliefs harming my child?"

You can't sweep the gender ghost under the rug, because they're there. So you have to take them out and take a look at them. And if you're parents, you always should be questioning yourselves: "Are any of these beliefs harming my child?"

Most parents love their children and believe that they're supporting their children. But what they offer may not sometimes be good for the child. And that's where gender ghosts come in: You may feel like you're supporting your child by saying "don't be ridiculous, boys don't wear dresses" [by] showing them how to be a boy in the culture, but at the same time you're giving them a very negative message about who they are.

"If you're parents, you always should be questioning yourselves: 'Are any of these beliefs harming my child?'"

This, quite frankly, is why we such high levels of anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, acting out at school — this kind of common misery among gender nonconforming kids who are getting messages like that. Those are our gender ghosts speaking.

Those are our gender ghosts speaking.

So we want to bring them out to the light of day and put them at war with what I call our gender angels. Those are the parts of us — and I think they're either there or can be harvested and fertilized — which open up our eyes to gender expansiveness, to the notion of gender diversity, to the notion that not following the rules does not mean you're sick or have a disease or that it's pathological, but that it's creative. That's why I call it the gender-creative child in the book. And it's just who these children are.

So we accept who these children are. I do believe that when we have people around gender ghosts and gender angels, we have a cognitive dissonance moment. The gender ghosts are telling you, "This is wrong," "This goes against the principles of my faith," etc. On the other side of that comes, "But I love my child very much. And I can either change those beliefs or hurt my child." So what I see over and over again among the parents I know is love conquers all — that sadly there are certain families where it does not happen, but happily there are families where their child profoundly changes them, and brings out the gender angels and poofs away their gender ghosts.

The next thing is that no matter where you are, you can find other parents. Fortunately, we have the internet. And there are now so many organizations that have chatrooms or places where parents can set up a [email] listserv with each other. And it has been a wonderful change for parents to not feel isolated in their experiences. And in the United States, there are now conferences all over the country where people can meet other parents, meet professionals, have the children meet each other — and even doing that once a year can make a tremendous difference.

Children can realize that they're transgender at a very young age. Or they might not — and still be transgender.

Ian Hitchcock/Getty ImagesGL: When should you expect a child to be more comfortable and confident in their identity, so you know it's perhaps a sure thing?

DE: Since you need to know that they're persistent and consistent over time, obviously you need time. It can't be one point in time. This is the most complicated thing about parenting a gender-creative child.

It can't be one point in time. This is the most complicated thing about parenting a gender-creative child.

It could pop up at any time. There's no one boilerplate. There are a subgroup of kids where you most likely know by the time they're in preschool. And they will so define early on, and they won't switch. So you could know in the first year of life if you have your eyes open. You might need more time to really get it in focus. But I'm having a number of parents who are now coming to talk to me about their three 3-year-olds, where they already got it [that] they have a transgender 3-year-old.

Now, everybody gets a little nervous about that. "How could a 3-year-old know their gender?" But for kids who are not transgender, we should expect them to know their gender by age 3. In our culture, we expect most kids to know if they line up in the boys' line or the girls' line. But we don't give the same latitude to transgender children. And because I don't think many of us understand that gender doesn't belong between their legs, but between their ears — it's their mind and their brain. So even among the littlest ones, their minds are already made up.

So even among the littlest ones, their minds are already made up.

"In our culture, we expect most kids to know if they line up in the boys' line or the girls' line. But we don't give the same latitude to transgender children."

But there are other kids for which it may not show up until they hit puberty. Often puberty is a point in which the body starts to change [and] all of a sudden it rises up, whatever was lying quietly and dormant, and they'll go, "Whoa, wait a second, this feels so wrong, and I'm miserable."

Now, a lot of kids are miserable through puberty. We know that. Any one of us could probably tell a tale.

But this is a different kind of misery. So if you're not transgender, if you imagine that you woke up one morning and your nose was turning into an elephant trunk, and you are going to have to live that way for the rest of your life, that's how it feels. Unless you would like to have an elephant trunk, but let's assume you wouldn't.

Kids are often traumatized, and that's a moment where they may say for the first time, "Well, you know what? I'm not a boy. I'm a girl. And I'm freaked out." And parents will often at that point be really confused, because they'll say, "But they weren't that way when they were toddlers. I never saw an inkling of this." And that doesn't mean it's not true.

I'm a girl. And I'm freaked out." And parents will often at that point be really confused, because they'll say, "But they weren't that way when they were toddlers. I never saw an inkling of this." And that doesn't mean it's not true.

Gender is a lifelong process. And it's not necessarily fixed at a time, although for many of us we're stable by age 5. That's the challenge for parents: It could show up at any point, and you'll have to start from that point on. Is it really persistent and consistent? Is it stable? Is it really a solution to something else, or not about gender at all? Tricky questions.

While parents should be willing to help their kids live their identities, they need to look for consistency

ShutterstockGL: I'm sure a lot of parents would worry, especially with a 3-year-old, that they would start treating the child differently — like letting the child transition — and it might turn out that the child was just gender nonconforming or going through what some people would call a phase. How do you balance out that concern?

How do you balance out that concern?

DE: By not going too fast. You raise a very important point: that, indeed, you don't want to jump to a conclusion by one point in time.

Now, I know that in developmental psychology, we have phases, [and] kids go through phases. So the common response from a pediatrician when a parent says, "My little girl doesn't ever want to wear a dress," is that she's just going through a phase. That's a possibility, but it's quite unlikely.

So what we want to do is give it some time to see whether this isn't a flash in the pan. But don't give it too much time, because then you have a miserable child.

"What we want to do is give it some time to see whether this isn't a flash in the pan. But don't give it too much time, because then you have a miserable child."

We do have some parents, particularly with all of the coverage of transgender children, who are too hot to try. They come with their false gender angels, claiming, "We are progressive. We will support our child. We believe in transgender children. And so we'll allow our child to transition from boy to girl." And then you meet the child and they're like, "Whoa, no, no, I'm just saying I want to try this out."

We will support our child. We believe in transgender children. And so we'll allow our child to transition from boy to girl." And then you meet the child and they're like, "Whoa, no, no, I'm just saying I want to try this out."

Here's what we have to help us with that: what I call the ex-post-facto test. And it's a pretty good one. It's not universally accurate. But if you got it right and you listen to the child, and you heard what they have to say, and what you heard is that they're not the child you think they are, and if you let them live full time in the gender they say they are, they get happier — not only a little bit happier, but it's also a remarkable transformation. So the ex-post-facto test says, "I got it right. I have a much happier, healthier child now that I finally listened and let them be who they are."

If they're not happy, and their misery goes up, you go, "Oh, maybe we should go look at that." It doesn't necessarily mean that they're not transgender. It may mean that they're going to a school that treats them terribly everyday, so there are things that are hurting them in the world. So you want to pay attention to what's going there.

So you want to pay attention to what's going there.

But you look for a happiness quotient. I see it as a professional. But I also hear it from parents who say, "Wow, I wish we listened earlier. I didn't realize. But I now have a different view."

To the extent trans people suffer disproportionately from mental health issues, it's due to discrimination

Transgender people protest North Carolina's anti-LGBTQ law.ShutterstockGL: For a lot of people, there's a lot of confusion in what the medical and scientific fields say about this. For example, I've seen some members of Congress cite gender dysphoria and the fact it's listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as proof — and these are their words, not mine — that trans people are mentally ill and disordered. But based on what you're saying and what other medical professionals and trans people have told me, to the extent some trans people have severe dysphoria — and not all trans people do — it should be treated by letting them transition without discrimination, not try to change their identity. Is that right?

Is that right?

DE: Yes. Absolutely.

I would start by saying that there are some of us who are still fighting to get any mention of gender out of the DSM for the exact reasons you just said: It pathologizes children around something that is not pathological.

There are parallels to homosexuality. We got it out of the book, and now we have marriage equality years later, which I think is relevant to recognizing one's diversity rather than pathology around sexual identity.

So a lot of people need an education.

"We want to help them get their gender in order — to help them live in their true gender self, their gender identity"

Even with the [gender dysphoria] diagnosis, that just means that someone is having an upset until they get their gender in order. And we want to help them get their gender in order — to help them live in their true gender self, their gender identity. And that should be the goal for any child and adults as well.

If there's any pathology, it lies in the culture, not in the child.

The only difficulty for some is they do get upset about how their body is showing up. That's not just around the culture out there — although when the culture says penis equals boy and vagina equals girl, and no one with a penis can be a girl, that seriously upsets people. But still, there might be an upset about your body.

So I think the one thing we do see that is inside the child who has a brain that's saying I have XX chromosomes but I'm a boy is that they have body mismatch sometimes, and it makes them unhappy, no matter how accepting everybody is.

But if there's any misery, it's probably because people aren't being allowed to live their lives based on who they are.

It's not just a social construct or biological. Gender identity is influenced by all sorts of variables.

GL: With some people, particularly those skeptical of everything that we're discussing, one source of confusion I've seen is that, on one hand, experts are telling them that gender is a social construct, but, on the other hand, experts are saying that gender identity is something inherent in kids that they might realize as young as 3, 4, or 5 years old. There's just a lot of confusion about those two concepts. So how do you explain it to people?

There's just a lot of confusion about those two concepts. So how do you explain it to people?

DE: Here's how I explain the whole notion of gender: It's not completely unrelated to culture, nor is it only a social construct. That's why I use the concept of a gender web — that every person's gender is spinning together nature, nurture, and culture. So we have to look at all three components, but there is a strong internal — and we can put it in nature, we can put it in nurture.

But gender is not just shaped by the outside, because otherwise we could spin these transgender kids into being cisgender [not trans]. And we can't; that would just make them go underground. So there is a constitutional, biological component that reasons people's gender, but it's not the only stream coming in.

So we have to consider all three: nature, nurture, and culture.

ShutterstockGL: So on the one hand you do have these roles that people expect of certain genders, and those are the social constructs. But on the other hand people inherently identify in certain ways, based on how they think of themselves, their bodies, and all of that. And all of these factors come together to influence somebody's gender identity.

But on the other hand people inherently identify in certain ways, based on how they think of themselves, their bodies, and all of that. And all of these factors come together to influence somebody's gender identity.

DE: Exactly. And I would say to this day, for why it is, it's still a mystery. We know a lot and we're learning a lot more about the "what is it?" but not so much the "why" of it.

Our goal this month

Now is not the time for paywalls. Now is the time to point out what’s hidden in plain sight (for instance, the hundreds of election deniers on ballots across the country), clearly explain the answers to voters’ questions, and give people the tools they need to be active participants in America’s democracy. Reader gifts help keep our well-sourced, research-driven explanatory journalism free for everyone. By the end of September, we’re aiming to add 5,000 new financial contributors to our community of Vox supporters. Will you help us reach our goal by making a gift today?

How to Know If Your Child Is Transgender

There is no simple test to tell if a child is transgender. Experts often refer to the idea of insistence, consistency, and persistence in terms of gauging whether a child is just going through a phase or not. This means the more insistent a child is, and the longer that insistence lasts, the less likely they are to change their mind about being a different gender.

Experts often refer to the idea of insistence, consistency, and persistence in terms of gauging whether a child is just going through a phase or not. This means the more insistent a child is, and the longer that insistence lasts, the less likely they are to change their mind about being a different gender.

While the following are possible signs of a child being transgender, there are no certainties.

What Does Transgender Mean?

Transgender – a person who experiences a gender identity or gender expression that is different from their assigned sex (at birth). Transgender teens tend to be an umbrella term, meaning in addition to individuals whose gender identity is opposite of their assigned sex, it includes individuals who do not consider themselves exclusively masculine or exclusively feminine (sometimes referred to as genderqueer, non-binary, bigender, pangender, or gender fluid. Some medical professionals categorize transgender as a third gender. Important to note is that transgender identification is independent of sexual orientation, and those who are transgender may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, asexual, etc.

Gender dysphoria – the distress or struggle a person endures due to the incongruence of the sex and gender they feel they are in comparison to the sex and gender they were assigned at birth. This means the assigned sex and gender do not match the person’s gender identity.

Possible Signs of Transgender Child

Many children engage in behavior that challenges the typical gender norms and stereotypes and do not identify as transgender at all. Nonetheless, there are some possible signs that could indicate a child is transgender or the presence of gender confusion in a child.

- Lack of interest in “gendered” activities – if your child is transgender or questioning their gender identity, you may notice them wanting to participate in activities typically associated with the opposite sex. Of course, a child who is not transgendered may be interested in toys and/or games associated with the other sex, so it is important to not automatically assume this behavior means your child is transgender.

- Hairstyle – typically, when a child is around 4 or 5 years old, they begin to want to have a say in their haircut and style. Transgender children tend to be much more vocal about their haircut and/or style and may protest if parents final say differs from what they want. Although every child is different, in general, transgender girls desire to have shorter hair, while transgender boys prefer the ability to grow their hair out.

- Disliking their name – if your child has a gendered-aligned name, it might be difficult for them to accept if they are trans. If you notice your child talking about changing their name, or requesting others call them by a different name (especially one that is the opposite gender), this could be a sign they are struggling with gender-related issues.

- Referring to themselves as the opposite gender – if you hear your child referring to themselves as the opposite gender (i.e. – your daughter says she is a boy), this could indicate they are transgender (or the presence of gender confusion).

Often times, a transgender child will say, “I am a girl/boy” rather than “I wish I was a girl/boy.” If you recognize this behavior in your child, ask them “why” they are referring to themselves as a boy/girl.

Often times, a transgender child will say, “I am a girl/boy” rather than “I wish I was a girl/boy.” If you recognize this behavior in your child, ask them “why” they are referring to themselves as a boy/girl. - Bathroom behavior – a clear sign of the presence of gender identity issues in any child is their use of bathrooms opposite of their gender identity at birth. Yet, more often than not, this is not the first change in bathroom behavior parents may notice. Instead, transgender or gender-confused children may have accidents due to feeling inclined to “hold it” instead of walk into the bathroom designated for the other sex. Hopefully, the child is able to verbalize this to a parent or trusted adult. But if you notice changes in your child’s behavior around using the bathroom, it is okay to ask.

- Pronoun changes – as more people come out as transgender, the need for gender-neutral pronouns becomes apparent. Personal pronouns are important for all individuals. But for those who are questioning their gender identity, personal pronouns can mean the difference between acceptance and rejection by others.

If your child is referring to themselves with gender pronouns opposite of their born gender identity, they could be transgender. Notice if your child feels more comfortable being referred to as the other sex; ask questions about their preferred pronouns.

If your child is referring to themselves with gender pronouns opposite of their born gender identity, they could be transgender. Notice if your child feels more comfortable being referred to as the other sex; ask questions about their preferred pronouns. - The desire to shop in the opposite gender’s clothing section – as with hairstyle, when a child is around 4 or 5 years old, they begin to want to have a say in what they wear. If, when you take your child shopping, they choose to shop in the opposite gender’s section, this might indicate your child is transgender. Of course, this could simply be a sign they want to experiment with different fashions, as many children dress and play in ways that challenge gender norms.

- Participating in opposite gender sports – while this is a large generalization, if your child expresses interest in participating in sports designated for the opposite gender, they may be transgender.

- Distress – an important indicator of any struggle or confusion in a child is the presence of distress.

In terms of a child who is transgender (or questioning their gender identity), distress may show up in various ways such as daily arguments regarding clothing choices before school.

In terms of a child who is transgender (or questioning their gender identity), distress may show up in various ways such as daily arguments regarding clothing choices before school. - Depression and/or suicidal thoughts – unfortunately, depression and suicidal thoughts are often present in transgender individuals and youth struggling with gender identity issues. The source of the depression may stem from a variety of concerns including:

- Difficulty accepting their identity,

- Fear of what it would be like to live as the gender they feel on the inside

- Rejection from peers, family, and/or friends

If you notice signs of depression in your transgender teen, or they are expressing the presence of suicidal thoughts, it is important to seek professional help.

How to Support Your Transgender Child

Whether you a sure your child is transgender or uncertain as to whether they are questioning their gender, it is always helpful to seek professional support. Doctors recommend finding a therapist or counselor who specializes in gender identity issues and children. Unfortunately, many parents do not seek outside intervention for their child, due to hopes of it just being a phase. Regardless of if your child is experiencing something temporary, or truly questioning their identity, having a mental health professional can be extremely helpful.

Doctors recommend finding a therapist or counselor who specializes in gender identity issues and children. Unfortunately, many parents do not seek outside intervention for their child, due to hopes of it just being a phase. Regardless of if your child is experiencing something temporary, or truly questioning their identity, having a mental health professional can be extremely helpful.

A therapist can help your child (and the family unit as a whole) decide which changes to make, and the timeline of those changes. A therapist can also refer you to other supports and resources such as support groups, medical doctors, etc. If your child is transgender or questioning their gender identity, it is vital you (as the parent) have a place to express fears and confront personal attitudes about gender while not in the presence of your child.

Additionally, there is no shortage of information available for parents in the process of navigating this difficult terrain. It is important to educate yourself, not only for the purpose of knowing possible signs to look out for, but also to ask educated questions to your child and professionals.

Polaris Teen Center

Polaris Teen Center | Website | + posts

Polaris Teen Center is a residential treatment facility for teens and adolescents suffering from severe mental health disorders. Our highly accredited facility is fully licensed and certified in Trauma Informed Care and is a part of the Behavioral Health Association of Providers (formerly AATA).

This is not a fantasy: How to understand that your child is

While preparing one article about transgender children, we noticed that parents of 3-5-year-old children are “rushing” to accept their different gender identity. And we asked ourselves, is such a reaction normal? Or do parents want to quickly come to terms with the new gender of the child and forget the moment of coming out like a bad dream? Other parents, on the contrary, begin to panic and “treat” such children, sincerely believing that they have a split personality or they just “play too much”. To dispel the myths about transgenderness and answer our questions, we asked a psychologist, family consultant-mediator Maria Fabricheva.

Maria, at what age can a child become aware of their gender identity?

According to the theory of standard analysis, transgenderness is not considered a personality disorder in today's world. Transgender is not a good/bad marker. It is important to understand that these are normal, good people with just such a feature. Being transgender does not mean that a person is bad, perverted or ill-mannered. This is not true.

As regards age, a child already at the age of three is at the stage of identity and strength. In English, the term "power" is used - strength, power. That is, the child has a need to study society, realize his strength, acquire communication skills, social adaptation and his gender identity. Therefore, if a child at the age of three declares that he is a boy or a girl, then such behavior is fully consistent with this stage of his development. So transgenderism can manifest itself precisely at this age.

How can you tell if this is not a child's fantasy?

It is quite difficult for parents at this age to understand whether it is a fantasy or not. Parents experience a culture shock: “My daughter doesn’t want to be a girl, my son doesn’t want to be a boy, so I’m a bad parent” or “Let’s treat the child.” Here you need to say “stop” and give parents time. There is nothing to treat here, because, as I said at the beginning, transgenderism is not a personality disorder. Therefore, it will not be possible to treat by force anyway, but it will only result in injury to the child, because they do not accept him as he is, but try to correct and make him comfortable. Exactly the same attitude towards teenagers who declare their homosexuality. Homosexuality, too, thank God, is no longer cured, but all the same, parents make attempts to change the child, but not for his good, but for the good of social norms.

Parents experience a culture shock: “My daughter doesn’t want to be a girl, my son doesn’t want to be a boy, so I’m a bad parent” or “Let’s treat the child.” Here you need to say “stop” and give parents time. There is nothing to treat here, because, as I said at the beginning, transgenderism is not a personality disorder. Therefore, it will not be possible to treat by force anyway, but it will only result in injury to the child, because they do not accept him as he is, but try to correct and make him comfortable. Exactly the same attitude towards teenagers who declare their homosexuality. Homosexuality, too, thank God, is no longer cured, but all the same, parents make attempts to change the child, but not for his good, but for the good of social norms.

In such situations, I advise parents to be calm. If a child who is biologically male claims to be a girl, do not rush to dress him up in dresses. We need to watch how it develops. And if it was a fantasy, if the child tried on another social role, for example, he likes to watch how his mother puts on makeup, and he decided to try to do it too, but in a conversation he accepted the information that makeup is for girls, not for boys, and he stopped imitating his mother, but began to imitate his father, which means that we are not facing a transgender child. If the child shows more and more similar interests, then you need to observe. However, it is still difficult to decide on your own in this situation. Just exhale and contact healthy psychotherapists who are ready to deal with this issue and are ready to help the child adapt.

If the child shows more and more similar interests, then you need to observe. However, it is still difficult to decide on your own in this situation. Just exhale and contact healthy psychotherapists who are ready to deal with this issue and are ready to help the child adapt.

Before adolescence, it is extremely difficult to change or correct anything. There can only be acceptance of the child and observation of him. And it is important to comply with social rules so as not to harm the child. In general, any diagnosis of a personality disorder is not given to children before adolescence. But already in adolescence, 13–15 years old, the child goes through the stage of identity and strength, gender association again, and secondary sexual characteristics begin to actively develop in him.

Education should not be aimed at bringing up not a transgender person, but a person who is healthy in terms of values, who will feel comfortable having such a feature. You should not make a tragedy out of this, but you should give the child the opportunity to fully manifest.

It is also important to remember that these are all elements of development. Children play games, trying on different roles. And it is very important for parents not to fantasize more than they really are. What I mean? At the stage of identity and power, a three-year-old child may declare that he is not a boy, but a girl, or not a girl, but a boy, but this cannot be a 100% guarantee that we are transgender.

- See also: My grandson is transgender

Well, is it possible that if a girl has short hair, then she will perceive herself as a boy? Or the boy likes to wear tutu skirts and his mother allows him to do this in public. Can such changes in appearance or encouragement of behavior somehow affect the child in the future?

Haircuts do not exactly affect. A child under three years old does not separate his “I” from his mother, he is in a healthy symbiosis with her. He is connected with the mother, so whatever happens to her, happens to the child. Symbiosis begins with uterine development and continues during the first year of life. Then the child goes through the first separation from the mother when he takes his first steps. During this period, his “I” is the whole world, he does not yet have a self-identity. Self-identity comes at 2.5 - 3 years, just when the child, looking at himself in the mirror, speaks of himself not in the third person, but in the first: "It's me." At the age of three, the child begins to study his body, ask various questions, looking for a gender difference.

Symbiosis begins with uterine development and continues during the first year of life. Then the child goes through the first separation from the mother when he takes his first steps. During this period, his “I” is the whole world, he does not yet have a self-identity. Self-identity comes at 2.5 - 3 years, just when the child, looking at himself in the mirror, speaks of himself not in the third person, but in the first: "It's me." At the age of three, the child begins to study his body, ask various questions, looking for a gender difference.

And, returning to your examples, if you say to a girl: “Tanya got a new haircut”, then she will understand that she, Tanya, has changed her hairstyle. If the girl is told in a certain key: “You look like a boy,” and the child catches this key, then he can decide that parents like it better when she looks like a boy. In this case, it is highly likely that the daughter will want to please her parents with such an appearance. This is not a natural transgender, but a scenario choice. And these are different things.

And these are different things.

There are situations when an expectant mother dreams, for example, of a daughter, but after having an ultrasound scan in the second trimester, when the biological sex of the child is clearly understood, she finds out that she will have a son and becomes very upset and seems to reject this fact. This situation can also affect the child's self-perception when, while in the womb, he feels that he will not be accepted in this gender. And I mean it quite seriously. The perinatal period is one of the most important in terms of acceptance. And then such stories can happen when a child by the age of three happily declares that he is not a girl, but a boy, or vice versa. Or it happens that dad wanted a son, but a daughter appeared. But the fact is that a small child does not verbally communicate with his parents, he reads the entire emotional background. And if, on a social level, parents smile and say that they are happy with any child, but on a psychological and emotional level they think completely differently, this affects the child, even if he is still inside the womb. And he can already make so-called protocol decisions. The scenario protocol is written deep in the body, it is not verbal. This is when the body, having made a decision, starts playing games. This is where the feeling of “I’m not in my body” comes from.

And he can already make so-called protocol decisions. The scenario protocol is written deep in the body, it is not verbal. This is when the body, having made a decision, starts playing games. This is where the feeling of “I’m not in my body” comes from.

And if a child of the same sex spends a lot of time with children of the opposite sex, can this in any way affect his self-identification?

A child can imitate, this is normal. Because in imitation the child develops and finds himself. Imitation and transgenderism are two very different things. I am in favor of explaining the difference to children, including gender. For example, when my son became interested in a bottle of nail polish, I explained to him that in our society it is not customary for boys to paint their nails. And if a child is interested in something, exploring this world, he asks his parents for normal intelligible explanations of how the world works and how a man differs from a woman, be it the body, the manifestation of emotions, wardrobe, self-care.

If a boy or girl resists, does not want to wear a certain type of clothing, and all this is very emotionally colored, up to tantrums, then here you also need to behave calmly and seek help from a specialist. Because such manifestations may indicate not so much about transgenderism, but that something else is not right, to the point that the child is simply unpleasant when certain material touches the body. All these nuances require research and clarification, especially in such subtle issues as gender and sexual orientation.

- See also: Non-Binary People: The Campus Experience

First of all, , I need to honestly answer the question, what happens to me when I see that something is wrong with my child? Am I nervous? I'm afraid? What am I afraid of? The fact that I will have a special child and then it will be difficult for him to adapt, and I want to know how to solve this problem? Or am I afraid that everyone will find out about this and say, whom did you give birth to, how bad are you? All these are normal processes, because we are living people, we have our own fears, complexes, worldview.

Secondly, , you need to clarify with yourself what is your personal attitude towards the LGBT community. What do you even know about these people? And this is your opinion, or the opinion of the post-Soviet society, when people were imprisoned? Remember that now is the 21st century, information is available, and before drawing conclusions, it is important to obtain normal knowledge.

Thirdly , when you understand that this is not a disorder, it is important to accept and understand that if you have such a child, then this has nothing to do with you as a person. If you have a special child, you remain a good person and a good parent. It is necessary to separate these planes. If this is ruining your life, then you need to figure out why. In fact, it doesn't interfere at all. These are two parallel processes.

Fourth, , it is important to understand what to do with it. Parents love their children unconditionally. And to love unconditionally is to accept a person as he is, and not try to change him for himself.

And to love unconditionally is to accept a person as he is, and not try to change him for himself.

Now about the search for a specialist. The task of a psychotherapist is not to re-educate someone, but to help a person accept his characteristics and adapt. It is important to find a specialist who does not make value judgments, but who will begin to clarify what you want. He will clarify with the child why he behaves in such a way in order to find out the true reason. Because it can be a real transgender, or it can be an imitation of someone, a tribute to fashion, etc. Now there are a lot of charismatic transgender artists, and children, looking at them, can light up and begin to imitate, but at the same time not be transgender. It's just that they may like a certain character and want to be the same. The task of the psychologist is to find out what the child really wants: to be public, to have a lot of followers on Instagram? This is the moment of research what is happening with this little person who is now developing and looking for himself in all planes of life - physiological, psychological, gender. Thus, the child joins a certain subculture, and when you start working with him, you understand that behind the external manifestations there are qualities - strength, courage, honesty.

Thus, the child joins a certain subculture, and when you start working with him, you understand that behind the external manifestations there are qualities - strength, courage, honesty.

There is another point - we all need attention. When a child, being in his gender, is invisible to his family, he lacks care and attention. But if a boy puts on a dress or a girl imitates the boys, then the children get a lot of attention.

Have you encountered transgender children in your practice?

I have not worked with children, but I have worked with gay people and transgender adults. They do not come with requests that they want to change their orientation back, no. They have inquiries about how to improve interpersonal relationships, how to open up to parents, and so on. I don’t work with teenagers now, because I have encountered such a problem when a child is brought to the so-called “correction”, while the parents are convinced that they personally have no problems. Yes, the child receives correction, support, but when he returns to the family, everything starts anew. There are a lot of conflict situations when the parent is dissatisfied with the work of the psychologist, because he brings the child in order for the psychologist to make him comfortable for the parent, and instead the psychologist begins to work with what is convenient for the child. I'm all for working with the whole family.

There are a lot of conflict situations when the parent is dissatisfied with the work of the psychologist, because he brings the child in order for the psychologist to make him comfortable for the parent, and instead the psychologist begins to work with what is convenient for the child. I'm all for working with the whole family.

When parents rush to accept a different self-identification of a child at an early age, can this be regarded as an act of selfishness on their part? Like, we will quickly come to terms with the fact that he is of a different gender and avoid psychological trauma in the future, because it is easier to accept the situation when the child is very small than already an adult.

Yes, it could be. Remember, at the beginning, I said that a healthy norm is important here? In our society, the game "either all or nothing" is popular. When parents rush to look for specialists and treat, or take a completely passive position, up to maintaining non-standard behavior, when their son is allowed to wear dresses, for example. The passive situation is not entirely good. As well as panic beyond measure. Neither situation is healthy. A healthy adult attitude is the middle ground—figuring out what's bothering you and doing what's good for both you and the baby. Find out if he is really transgender and how to help him adapt, or if he lacks your attention and has found a way to get it. In the second case, the issue of correction is solved much easier - if you pay attention to him qualitatively, then his behavior will begin to correspond to his gender. If we talk about the first case, then the task here is more complicated, because in the future the child will have hormone therapy, possibly a sex change operation, he needs to finish school, get a higher education, find a job, find himself, have financial support in order to be able to live in comfort with you, and at the same time not be weighed down by your peculiarity.

The passive situation is not entirely good. As well as panic beyond measure. Neither situation is healthy. A healthy adult attitude is the middle ground—figuring out what's bothering you and doing what's good for both you and the baby. Find out if he is really transgender and how to help him adapt, or if he lacks your attention and has found a way to get it. In the second case, the issue of correction is solved much easier - if you pay attention to him qualitatively, then his behavior will begin to correspond to his gender. If we talk about the first case, then the task here is more complicated, because in the future the child will have hormone therapy, possibly a sex change operation, he needs to finish school, get a higher education, find a job, find himself, have financial support in order to be able to live in comfort with you, and at the same time not be weighed down by your peculiarity.

Should I turn to the LGBT community for help?

In order to understand what is happening with the child, you can contact, but even there it is important to find understanding people. They will help and find a psychologist, and clarify many issues. Therefore, parents should take off the crown and ask for help, for example, famous transgender people. Believe me, these people will not drag your child to their side, because they will not wish anyone to go the way they have overcome. On the contrary, these people will support, give information, explain what happened to him when he was 3 years old, 6 years old, 12 and 28, because they are at the core of this problem, and like no one knows what awaits this child.

They will help and find a psychologist, and clarify many issues. Therefore, parents should take off the crown and ask for help, for example, famous transgender people. Believe me, these people will not drag your child to their side, because they will not wish anyone to go the way they have overcome. On the contrary, these people will support, give information, explain what happened to him when he was 3 years old, 6 years old, 12 and 28, because they are at the core of this problem, and like no one knows what awaits this child.

Prepared by: Tanya Kasyan, Ira Kerst

Illustration by Maria Kinovich

— Read also: Confidential and non-toxic: 7 rules that will help build a healthy relationship with a child Transgender children and adolescents | On Narrative Practice, Therapy, and Community Work

excerpt from Esben Esther Pirelli Benestad, "Gender: Children, Adolescents, Adults, and the Role of Therapist," published in Queer counseling and Narrative therapy, 2002, ed. by David Denborough, Dulwich Center Publications, Adelaide, Australia)

by David Denborough, Dulwich Center Publications, Adelaide, Australia)

translated by Daria Kutuzova

For some children, this world is like a foreign country, full of incomprehensible words and strange customs. No matter how hard they try to comply with these incomprehensible "laws of nature", they still fail.

Introduction

photo by Natalia Savelieva

In order to realize their beliefs about gender (or genders), many adults leave their families, friends, studies, and work. They want to live in a context that matches the gender they experience. There is a huge price to pay to give up what you have in order to be yourself. But for some people, this is the only way to be at least to some extent happy. The younger the person, the more difficult it is for him or her to break out of living conditions that are not ready to accept him as he is. It usually happens that children and teenagers depend on significant adults to survive. And if a child or teenager demonstrates their gender in some way that inspires anxiety and fear in relatives and friends, then very specific problems arise.

And if a child or teenager demonstrates their gender in some way that inspires anxiety and fear in relatives and friends, then very specific problems arise.

I am a sexologist and family therapist. I openly admit that I am bigender. This position in Norwegian society gave me the opportunity to hear many stories. Parents and child development professionals have told me that a fairly large number of children exhibit "cross-gender" behavior at one time or another. Most often, as I understand it, this is perceived as a child's game, experimenting with the ways of self-expression adopted by adults - and therefore is not considered a problem. The longer cross-gender behavior lasts, the more areas of life it affects, the more likely it is that parents and / or other significant others will begin to worry about the future of the child, and in particular, about his mental health.

The prevalence of cross-gender behavior and the concern it causes in people has led to the development of diagnostic and evaluation systems.

According to the DSM-IV, "gender identity disorder" is diagnosed when four (or more) of the following are present:

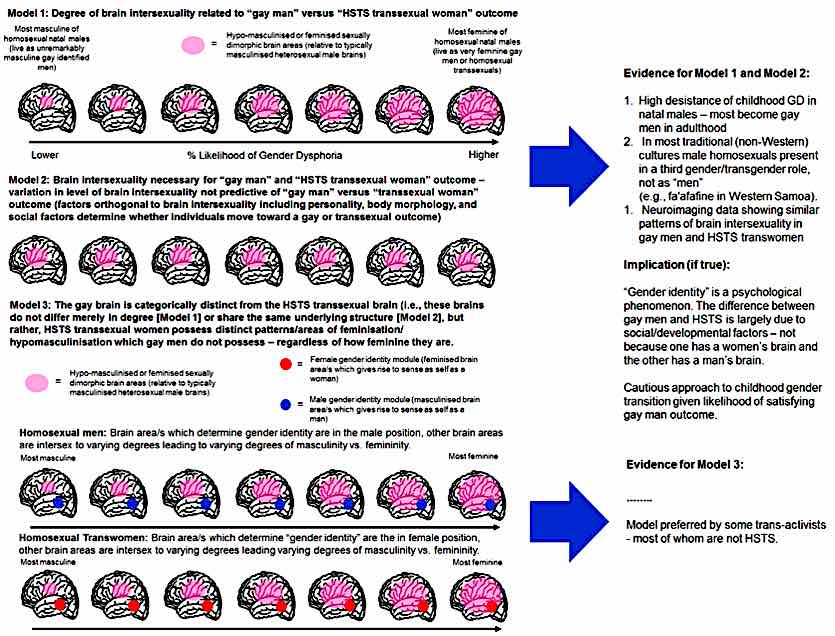

The DSM-IV also states that, by adolescence or early adulthood, approximately three-quarters of boys who had a "gender identity disorder" as children report a homosexual or bisexual orientation, but without a "gender identity disorder". Most of the remaining respondents report heterosexual orientation without "violating gender identity". Some teens and young adults identify as women and request gender reassignment surgery, while others continue to live "in a state of gender confusion and dysphoria". It may be of interest to the reader to know that no statistics are provided for girls because there is very little "clinical material" - girls who were diagnosed with gender identity disorder as children.

It may be of interest to the reader to know that no statistics are provided for girls because there is very little "clinical material" - girls who were diagnosed with gender identity disorder as children.

Worried adults sometimes turn to doctors, psychologists and psychotherapists about their children's cross-gender behavior. This happens much more often if, according to somatic characteristics, the child is male. Among professionals there is no unanimity about how to proceed in such a case. The International Association for the Study of Gender Dysphoria, however, has published some guidelines. The following is a quotation from the sixth edition of this publication, issued in 2001:

Phenomenology

Gender identity disorders in children and adolescents differ from similar disorders in adults in that rapid and dramatic developmental processes (physical, psychological and sexual) take place during childhood and adolescence. Gender identity disorders in children and adolescents are complex phenomena. A child or adolescent may experience a discrepancy between the phenotypic relationship to one or another sex - and the subjective experience of gender identity. In this case, a person experiences severe distress, often accompanied by emotional and behavioral problems. Outcomes are varied, especially in the case of pre-pubertal children. Few people who experience gender identity disruption during childhood and/or adolescence become transgender, but many develop a homosexual orientation.

A child or adolescent may experience a discrepancy between the phenotypic relationship to one or another sex - and the subjective experience of gender identity. In this case, a person experiences severe distress, often accompanied by emotional and behavioral problems. Outcomes are varied, especially in the case of pre-pubertal children. Few people who experience gender identity disruption during childhood and/or adolescence become transgender, but many develop a homosexual orientation.

Common signs of a conflicted gender identity include, in children and adolescents, an overt desire to be of the other sex; dressing in clothes typical of another gender; preference for games and toys that are usually considered typical of the gender with which the child identifies; refusal of clothes, games, toys and demeanor, usually expected from the gender that the child is "assigned"; preference for communicating with children of the gender with which the child identifies; aversion to one's own sexual organs and their functions. The diagnosis of "violation of gender identity" is more often given to boys than to girls.

The diagnosis of "violation of gender identity" is more often given to boys than to girls.

There are phenomenological differences between the way children and adolescents present their gender and gender problems and the way delusions and other psychotic symptoms are shown at that age. Delusional ideas about one's own body or gender occur within psychoses, but they are distinct from the gender identity disorder phenomenon. Gender identity disorders in childhood are not the same as gender identity disorders in adulthood and do not always lead to them. The younger a child is when diagnosed with a gender identity disorder, the less certain the outcome is.

Using language like this, the DSM-IV and the International Gender Dysphoria Research Association see the child's condition as a "disorder", a disorder, a disease that will need to be treated, corrected in the future, etc. However, this diagnosis, made in childhood, persists into adolescence and later in only about 1% of cases. It is interesting to note that the sixth edition of the guidelines cited above offers a much broader range of drug treatment at an earlier age compared to the fifth edition.

It is interesting to note that the sixth edition of the guidelines cited above offers a much broader range of drug treatment at an earlier age compared to the fifth edition.

Challenges

The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and the Gender Dysphoria International Association's guidelines for action raise many questions. Below I list a set of questions and problems that I will discuss in detail in this article.

- Knowing that there are many children and adults who are bodily markedly different from both gender majorities (so much so as to be excluded from both), and knowing that many adults claim to be of both sexes or neither to one nor the other sex, can we meaningfully use the term "opposite sex"?

- Do the contemporary norms and standards of Western society related to the perception and expression of gender provide sufficient opportunities to include and reflect the diversity of genders and gender-related human characteristics and qualities? And if not, does it not happen that we diagnose, treat and thus pathologize people based on the shortcomings of our norms and standards?

- Do unusual experiences and expressions of gender and/or sexual orientation lead to suffering in and of themselves, or do the problems that certain people face have more to do with the refusal of others to acknowledge them for who they are?

- When is it legitimate to question the reality of subjective experiences?

- Are we going to call certain forms of gender expression disorders or violations at all, or will we say that certain forms of gender expression upset us, break the way we are used to?

- If some people have traits and properties that are not yet fit into existing cultures, what ethics should guide professionals (clinicians) when working with these people?

- Is it ethical to send a child with an unusual combination of primary sexual characteristics for surgery, or is it the task of doctors to correct the shortcomings of generally accepted ideas about gender?

- Is it possible to formulate "rules of conduct" for professionals and society in general to avoid such misfortunes as suicide, self-harm, self-hatred, self-loathing, alcohol and drug abuse, psychiatric and social problems in those people who do not Can they achieve a sense of belonging, recognition because of their particular gender(s) or sexual orientation?

I will return to these questions and concerns in a moment.

The fate of children with cross-gender behavior

In total, 3-4% of the population of children demonstrate significant cross-gender behavior. Very few of those who are diagnosed as having a gender identity disorder as children grow up to be transgender. More often, these children grow up to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

Studies show that a large percentage (70-80%) of gay men and lesbian women exhibited cross-gender behavior in childhood on a scale sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of gender identity disorder (Carrier, 1986). Similarly, even in childhood, future gays and lesbians are highly likely to be recognized. During adolescence, this group faces a lot of difficulties and dangers. Studies have shown that lesbian, gay, and transgender adolescences are much more difficult and have a much higher risk of suicide than heterosexuals of the same age (Hegna, Kristiansen & Moseng, 1999).

So, there is a group of children about whom we can say that with a high probability they will have a hard time in adolescence. Accordingly, we have some time to take some action. I believe it is our responsibility to prevent, as far as possible, the dangers, hardships and troubles that we know many gay, lesbian and transgender adolescents may face. To prevent these complexities, we must first understand the intricacies of gender identity.

Accordingly, we have some time to take some action. I believe it is our responsibility to prevent, as far as possible, the dangers, hardships and troubles that we know many gay, lesbian and transgender adolescents may face. To prevent these complexities, we must first understand the intricacies of gender identity.

Gender: definitions of concepts and terms

Terms related to gender are used in different ways. There are many words, and these words convey many meanings. There is often confusion about how certain words are used by professionals and ordinary people. People can use the same words, but the connotations can be completely different. Let's take the word "feminine" for example. This word includes various meanings: the behavior of some women; the behavior of some gay men; outlines of the human body. How then are "feminine" and "feminine", "masculine" and "masculine" connected? Is the "female body" always "feminine", or can it be "feminine" and "masculine" at the same time?

Our perception of our own gender is based on subjective experience and on those concepts, cultural tools of understanding, which we borrow from the surrounding social environment. When the environment does not contain the necessary words and concepts, a person has to invent his own, otherwise he (a) will suffer from a sense of his own “wrongness”, or, worse, from a sense of his own “non-existence”, “non-existence”.

When the environment does not contain the necessary words and concepts, a person has to invent his own, otherwise he (a) will suffer from a sense of his own “wrongness”, or, worse, from a sense of his own “non-existence”, “non-existence”.

We should not demand from children and adolescents that their path to self-understanding lies through the creation of a new conceptual system for themselves. Children depend on the cultural tools of understanding offered by the adult world. Accordingly, one of our tasks as professional professionals is to create new and “re-invent” old words and concepts so that all existing and emerging diverse phenomena in Genderland are described in a way that is recognizable to all interested parties.

Clarity of terminology is very important and therefore I will provide a set of descriptions and definitions here. These terms serve as a background for understanding gender.

" Somatic sex " refers to the body as it appears from the outside. A newborn baby may be somatically male, female, hermaphrodite, or not fit into any of the three categories above. Somatic gender, determined through observation by others, forms expectations from a person's social gender status. This is a powerful affirmation of gender, but it is based on the perception of people who are “out there” (Almaas & Benestad, 1993).

A newborn baby may be somatically male, female, hermaphrodite, or not fit into any of the three categories above. Somatic gender, determined through observation by others, forms expectations from a person's social gender status. This is a powerful affirmation of gender, but it is based on the perception of people who are “out there” (Almaas & Benestad, 1993).

" Reproductive sex " refers to a person's ability to reproduce, regardless of whether the person has realized this ability or not. There are four possibilities: can or could become a mother, can or could become a father, can or could become both a father and a mother (theoretically possible for some hermaphrodites), and never could become neither father nor mother. Reproductive sex cannot be changed. This is the most significant affirmation of gender (especially for those who have congruent somatic sex and subjective experience of gender), but for transgender or non-fertile people, it can be a source of very difficult and painful experiences (Almaas & Benestad, 2001).

" Gender Identity " refers to a person's subjective perception of himself as female, or male, or both-male-and-female, or neither-male-nor-female. Gender identity is largely formed under the influence of generally accepted ideas about what it means to "be a man" or "to be a woman." As a rule, a person's gender identity is stable from the age of 4-5, but for some people it changes over time (Almaas & Benestad, 1993). Gender identity is a powerful affirmation of gender and can overpower both somatic sex and body awareness (Almaas & Benestad, 1993; Zucker et al., 1999).

" Body consciousness " (body consciousness) denotes a person's experience of his own body. Gendered body awareness includes the subjective perception of one's own genitals and other "gendered" body parts. Body consciousness can be affected, for example, when a person is sexually abused, or when there is a discrepancy between the subjective experience of one's own gender and the subjective experience of one's own body. The consciousness of the body can be the consciousness of a male body, a female body, a hermaphrodite body, or another type of body, and this is a powerful affirmation of gender (Almaas & Benestad, 1993).

The consciousness of the body can be the consciousness of a male body, a female body, a hermaphrodite body, or another type of body, and this is a powerful affirmation of gender (Almaas & Benestad, 1993).

“ Body image ” is what we present to others. If we compare somatic sex to a box in which any gender can be hidden, then body image is a box in a wrapper. A person may have the body of a man, a woman, a hermaphrodite, or otherwise. From the point of view of self-presentation in culture, a person can show the world "wrappers" that inform about femininity, masculinity, androgyny or non-gender qualities. “Body image” is a gender affirmation that is most easily modified, such as by wearing atypical clothing. "Body image" is a way of relating to the outside world and (trying to) be accepted by it (Almaas & Benestad, 1993).

" Gender role " refers to the range of interests, choices, behaviors, actions, styles that society considers "male" or "female". By defining gender role in this way, we mean that its content is completely arbitrary, and this point of view is not shared by all specialists (Sullivan, Bradley & Zucker, 1995). However, it is widely believed that the same person can embody both masculine and feminine traits, and thus, in terms of gender role, be androgynous. Before the feminist and queer movements began to have a significant impact on Western society, gender roles in it were considered powerful affirmations of gender. However, as gender role norms have expanded and become more diverse, their impact on gender affirmation has waned. Some people who have a female body, but subjectively experience both female and male gender identity, seek confirmation of their gender through participation in "traditionally male" activities, such as putting out fires or playing football. Some people who have a male body but prefer to wear women's clothes, and some transgender people refuse to take part in "male" activities while dressed.

By defining gender role in this way, we mean that its content is completely arbitrary, and this point of view is not shared by all specialists (Sullivan, Bradley & Zucker, 1995). However, it is widely believed that the same person can embody both masculine and feminine traits, and thus, in terms of gender role, be androgynous. Before the feminist and queer movements began to have a significant impact on Western society, gender roles in it were considered powerful affirmations of gender. However, as gender role norms have expanded and become more diverse, their impact on gender affirmation has waned. Some people who have a female body, but subjectively experience both female and male gender identity, seek confirmation of their gender through participation in "traditionally male" activities, such as putting out fires or playing football. Some people who have a male body but prefer to wear women's clothes, and some transgender people refuse to take part in "male" activities while dressed.

" Sexual orientation " denotes a person's response to gendered stimuli. A person may experience sexual and / or emotional attraction only to women (not to everyone), only to men (not to everyone), and to men and women (not to everyone), and / or to hermaphrodites, transvestites, transgender people and others who do not fit into existing gender norms.

Some people are indifferent to gendered stimuli and may be considered asexual. Sexual orientation can be formulated in the form of labels "heterosexual (ka)", "gay", "lesbian", "bisexual (ka)". These labels are usually based on descriptions given "outside" and may change when viewed from the point of view of the person's subjective experience. A transsexual woman (MtF) may consider herself heterosexual, while strangers may say “he is homosexual” about her. Sexual orientation plays an important role in asserting/confirming gender. Sexual orientation may change over time (Almaas & Benestad, 1993; Sullivan, Bradley and Zucker 1995).

" Gender belonging " (gender belonging) describes the permanent or temporary state of confirmed or at least declared gender. Gender affirmation/confirmation is carried out at seven levels: somatic sex, reproductive sex, gender identity, body consciousness, body image, gender role and sexual orientation. Opportunities for gender identity: to be accepted as a man, to be accepted as a woman, to be accepted as both male-and-female, to be accepted as transgender, to be accepted as someone else (not yet designated by a special word). Gender affiliation is the goal of behavior and experiences associated with the confirmation of gender. Over time, the experience of gender can change. Positive gender identity is experienced when other people perceive a person's gender in the same way as he (s) himself (s). Transgender people go through a more or less lengthy process of finding a gender that matches their subjective experience of their own gender identity (Almaas & Benestad, 1993; Doom, 1997).

" Gender Cruising" describes the growing tendency to experiment, mix, innovate and cultivate certain forms of gender expression. Gender cruising includes both the lives and work of women in "typically masculine" conditions and men in "typically feminine" environments, but it also describes the experiences of people who transcend gender in the sense that we are used to. understand him. The gender journey can be undertaken as a deliberate opposition to a culturally imposed dichotomy of gender, and/or can be an intentional or accidental means of affirming gender (Almaas & Benestad, 1999).

" Gender crossing " (gender crossing) is the transition from one gender to another, either permanently or temporarily. This term is generally in line with normative notions that there are only two genders (Almaas & Benestad, 1993).

" Biological gender (genus) " describes the biological substrate - the basis for various ideas about gender. Darwinists use this term to refer to the ability to reproduce. Some researchers of the transgender phenomenon associate "biological gender" with gender identity (influence on the central nervous system), while others associate "biological gender" with the presence or absence of certain body features. There is always a debate around this term about what and how much in the variety of forms of expression of gender is biologically determined (Almaas & Benestad, 1999).

Darwinists use this term to refer to the ability to reproduce. Some researchers of the transgender phenomenon associate "biological gender" with gender identity (influence on the central nervous system), while others associate "biological gender" with the presence or absence of certain body features. There is always a debate around this term about what and how much in the variety of forms of expression of gender is biologically determined (Almaas & Benestad, 1999).

" Gender Dichotomy " describes the notion that there are only two distinctly and unequivocally defined sexes/genders; if there are scientifically or culturally recognized alternatives to this, within the "gender dichotomy" they are denied or ignored. This dichotomy is subtly but very powerfully supported by expressions and phrases such as “opposite sex”, “cross-gender behavior”, etc. woman”, “not being able to determine who you are: a boy or a girl”, “basic self-perception of own belonging to the male or female sex”, and many, many others.

" Dissatisfaction with one's own body " describes the subjective experience of having a body that does not correspond to one's ideas, for example, one's own gender. Body dissatisfaction is a widespread phenomenon, with an increasing number of people dissatisfied with their body as a whole or its individual parts, which poses many challenges for the cosmetic industry and/or plastic surgery (Almaas & Benestad, 1999). Dissatisfaction with one's own body can also take the form of "dislike of one's own sexual organs", "aversion to the anatomical characteristics of the body" (Blanchard & Steiner, 1990) and "long-term discomfort associated with anatomical sex characteristics" (Sullivan, Bradley and Zucker, 1995).

" Uncertainty of sexual characteristics ". Within the medical culture, children born with indeterminate somatic sex characteristics are considered "freaks". And this despite the fact that adults (with genitals that cannot be unequivocally defined as either male or female) claim the right to be as they are. These people represent the "third alternative" on the somatic sex scale, and they form an essential part of the group that cannot and will not conform to the dichotomous standards of somatic sex.

These people represent the "third alternative" on the somatic sex scale, and they form an essential part of the group that cannot and will not conform to the dichotomous standards of somatic sex.

Gender paradigms . There are paradigms supported by science, law, religion and worldly ideas regarding what combinations of somatic sex, gender, manifestations of love, sexual behavior, forms of expression of sexuality should be considered "correct". These paradigms are being deconstructed, influenced, among other things, by the critical gaze of the transgender and gender-indeterminate communities.

How to work with children and adolescents who express their gender in unusual ways

Having considered these terms and the complexities of gender, let's now return to the question of how to work with children and adolescents whose gender expressions seem unusual.

Gender travel, cross-gender or transgender behaviors and expressions of children, adolescents and youth often cause anxiety and confusion for their significant others. In some cases, it comes to the point that parents, other family members and other adults turn to doctors and psychotherapists to “cure him/her” and/or help these unusual children and adolescents cope with possible problems in the field of gender identity and/or sexuality. orientation.

In some cases, it comes to the point that parents, other family members and other adults turn to doctors and psychotherapists to “cure him/her” and/or help these unusual children and adolescents cope with possible problems in the field of gender identity and/or sexuality. orientation.

This raises certain ethical questions for us. Is it ethically justifiable to treat children who are diagnosed with gender identity disorders if their behavior, even if it is not in accordance with the norms, does not harm anyone? Is it ethically justified to treat the early manifestations of homosexuality, a human situation as complete as heterosexuality? Moreover, in most cases, cross-gender behavior in childhood often does not lead to homosexual identification in adulthood (Green, 1968, 1974, 1987; Sullivan, Bradley & Zucker, 1995; Zucker et al. 1999), it is quite common for children who exhibit cross-gender behavior to grow up into adult heterosexuals with conventional gender identity. Therefore, it is very difficult to prove the existence of a “therapeutic effect” of a child’s treatment, a positive impact of corrective measures on gender-colored behavior in the future and on a person’s gender identity.