How to deal with an ocd child

The Parents' Role in OCD Treatment

When you’re the parent of an anxious child, you assume that your role is to provide reassurance, comfort, and a sense of safety. Of course you want to support and protect a child who is distressed and, as much as possible, avert her suffering. But in fact, when it comes to a child with an anxiety disorder like obsessive compulsive disorder, trying to shield her from things that trigger her fears can be counterproductive for the child. By doing what comes naturally to a parent, you are inadvertently accommodating the disorder, and allowing it to take over your child’s life.

That’s why parents have a surprisingly important role in treating anxiety disorders in children. The gold standard in pediatric OCD treatment is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy called exposure and response prevention. The therapy involves “exposing” the child to her anxieties in a gradual and systematic way, so she no longer fears and avoids those objects or situations; “response prevention” means she is not allowed to perform a ritual to manage fears. Because parents become so involved in their children’s OCD, research has shown that including parents in treatment and assigning them as “co-therapists” improves effectiveness.

The fear hierarchy

In therapy the child, parents, and therapist create a “fear hierarchy” in which they collaboratively identify all of the feared situations, rate them on a scale of 0-10, and tackle them one at a time. For example, a child with fears about germs and getting sick would repeatedly confront “contaminated” situations and objects until her fear subsides and she can tolerate the activity. The child would start with a low-level anxiety item, such as touching clean towels, and build to more difficult items such as holding half-eaten food from the trash.

Response prevention involves preventing the child from performing the behavior that serves to decrease the anxiety. For example, a boy with a fear of germs would have to abstain from washing his hands after touching the doorknob, or the garbage. Through gradual exposure he learns that what he “fears” usually does not come true, so that new learning can take place. It also teaches him that he can tolerate uncomfortable feelings.

Through gradual exposure he learns that what he “fears” usually does not come true, so that new learning can take place. It also teaches him that he can tolerate uncomfortable feelings.

Much of the work in CBT involves practice outside of sessions, requiring parents to participate in the treatment. Children are assigned “homework” and asked to continue practicing facing their fears in a variety of settings. Since exposure and response prevention evokes anxiety and requires considerable follow-up, family involvement and support is essential.

For a child with a fear of contamination, the parents may encourage him to do the dishes, or to become a “human vacuum cleaner,” which is what clinicians call picking up small scraps of garbage from the carpet. A child with fears of vomiting might write a comic about “Vomit Man” in session with his therapist, and then practice reciting it aloud to his parents.

The problem with reassurance

But parents have a bigger role than backup when it comes to practicing exposures at home. Since OCD can be a crippling disorder for children, relatives often become excessively involved in a child’s symptoms in order to help the child function. For instance, many children with OCD, as well as other anxiety disorders, seek constant reassurance from family members. Reassurance-seeking is used by children to manage fears, and many parents provide it, even though it’s excessive, in order to make their child feel better in the moment.

Since OCD can be a crippling disorder for children, relatives often become excessively involved in a child’s symptoms in order to help the child function. For instance, many children with OCD, as well as other anxiety disorders, seek constant reassurance from family members. Reassurance-seeking is used by children to manage fears, and many parents provide it, even though it’s excessive, in order to make their child feel better in the moment.

Reassurance-seeking is one of the many forms of “family accommodation.” This phenomenon refers to the manner in which family members participate in the rituals the child uses to manage his anxiety, as well as how they modify personal and family routines in order to accommodate him.

Many children suffering from OCD are unable to tolerate uncertainty, and they ask their parents to provide them with definitive answers. For example, it is not uncommon to hear an anxious child ask their parent “Am I going to get sick from eating this?” or “Is everything going to be okay?” although the answer may have already been provided several times.

Parents can easily become frustrated because they feel like no matter how many times their child’s questions are answered, they are never satisfied. Answering their child’s questions becomes an endless cycle, and the child never learns that he can indeed tolerate the uncertainty.

Accommodating fears

There are many other forms of accommodation. Families may stop taking vacations, going out to restaurants, or even change the way they speak in order to avoid anxiety-provoking situations for their child. They may avoid particular names, numbers, colors, and sounds that trigger anxiety.

“OCD can be very overwhelming to families and can really interfere with how families can normally function,” says Jerry Bubrick, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute who specializes in anxiety and OCD. “The family decisions are made to accommodate the anxiety, rather than the best interests of the family.”

To the family of a patient we’ll call John, a 12-year old boy who was treated at the Child Mind Institute for OCD, this is all too familiar. John had fears about contamination and gaining weight and thus he avoided any food that was considered “unhealthy,” took up to seven showers a day, and didn’t play with his siblings or hug his parents in the belief that they were contaminated.

John had fears about contamination and gaining weight and thus he avoided any food that was considered “unhealthy,” took up to seven showers a day, and didn’t play with his siblings or hug his parents in the belief that they were contaminated.

“We didn’t go out to a restaurant for months,” said John’s mother. “He didn’t have any friends come over. We didn’t have any of our friends come over. Our house was a safe place.”

But accommodating John’s anxiety didn’t stop it from taking over more and more of his life. John’s mother described the peak of his OCD as an extremely challenging time for her family. “It was really hard because it’s like we had lost our son. He was so trapped in the OCD. We couldn’t physically touch him. There was no spontaneity anymore. We couldn’t even sit across the table and talk anymore.”

Reinforcing anxiety

While the parents who accommodate their child are well intentioned, family accommodation is known to reinforce their child’s symptoms. Since anxiety is maintained through avoidance, family members who accommodate their child are causing the symptoms to become even more fixed.

Since anxiety is maintained through avoidance, family members who accommodate their child are causing the symptoms to become even more fixed.

“Before I knew what accommodation was, I thought I was helping,” said John’s mother. “I was heartbroken when I found out the definition of accommodation. I was devastated to know I was feeding the OCD instead of helping John.”

Naming the child’s OCD is one way to reduce the stigma associated with it, and makes the child feel like the anxiety is not who she is. For example, a child may name her OCD “The Bully” or “The Witch.” John’s mother continues: “Divorcing the OCD from John has been huge. Now the family has a common enemy, everyone is in on the battle. Before it was an unnamed invader. Now we know who we’re fighting.”

Building coping skills

Through treatment, parents learn new ways to respond when their children get “stuck” and how to encourage their child to rely on coping skills or to “boss back” their anxiety, instead of relying on their parents to help them through it. The children eventually become much more independent, and the parents may start to realize that anxiety is no longer in charge of their families.

The children eventually become much more independent, and the parents may start to realize that anxiety is no longer in charge of their families.

Grandparents and siblings can also become involved in family accommodation, although they are not typically included in treatment as regularly as parents are.

“Since grandparents and siblings are more a part of the child’s outside world, they may be more likely to accommodate because they want to maintain peace,” said Dr. Bubrick. “They should be a involved in the treatment so they don’t undermine it.”

Helping kids face fears

Through treatment, family members learn to help their children face their fears instead of avoiding them. Instead of comforting the child, it becomes the parent’s job to remind him of the skills he has developed in treatment and to use them in the moment.

“Now I’m helping John and I’m not feeding the OCD,” said John’s mom. A lot of that is letting John know that he has strength to fight the OCD. Reminding him of the strategies instead of making the world better for him.”

Reminding him of the strategies instead of making the world better for him.”

Managing OCD in Your Household

As you already know, when your child has OCD, the entire household is affected. Siblings and parents, alike may have their routines interrupted or feel pressured to accommodate your child with OCD by taking part in rituals. But more than anything, it is important that your child with OCD feel loved and supported, even when that means using “tough love” to enforce homework and exercises assigned by your child’s therapist.

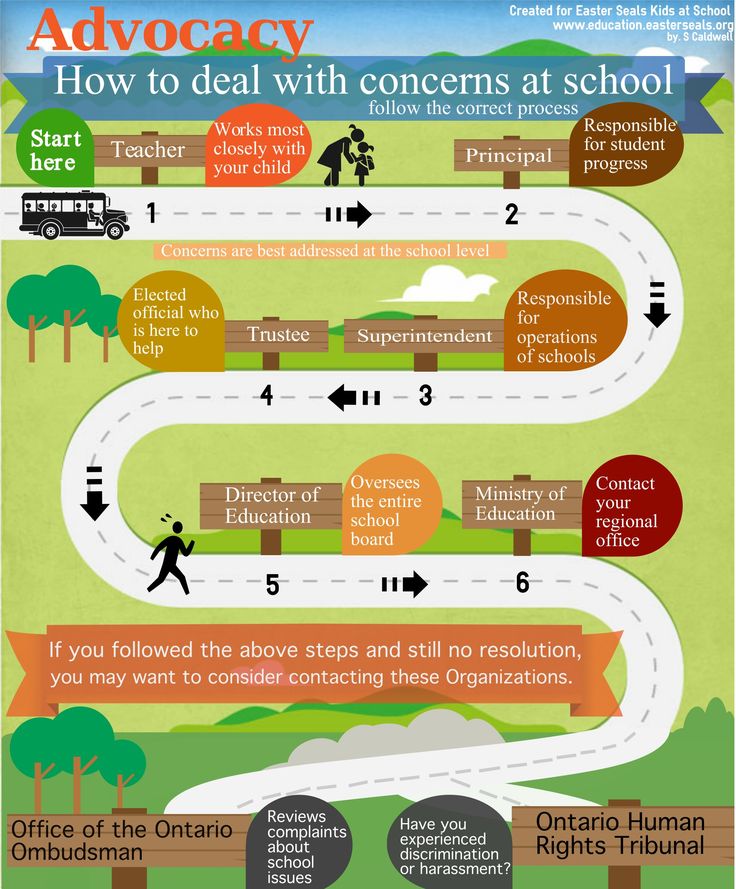

In an effort to strengthen relationships between individuals with OCD and their family members and to promote understanding and cooperation within households, we have developed the following list of useful guidelines for family members to be tailored for individual situations. If you are unsure how to employ or implement some of these guidelines, don’t be afraid to ask your child’s OCD therapist for help — your therapist should be accustomed to working with the entire family when necessary.

1. Recognize signals

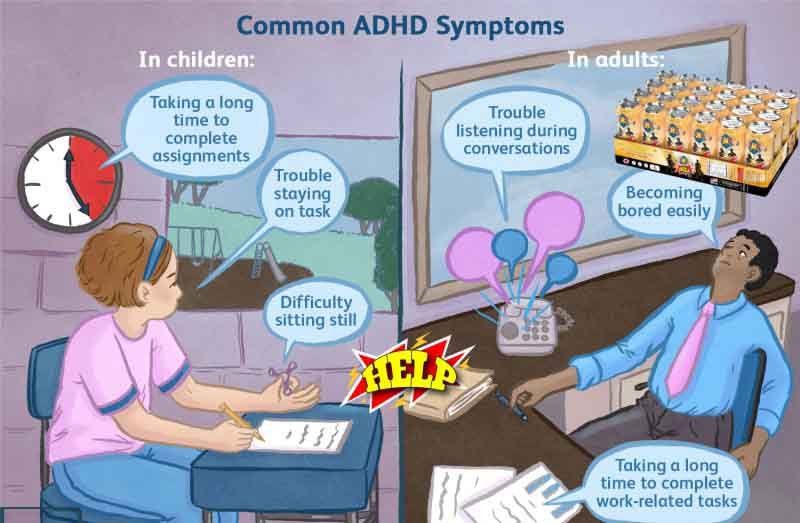

This first guideline stresses that family members learn to recognize the “early warning signs” of OCD symptoms. Your child may seem fine from the outside but may suddenly experience a wave of intrusive thoughts, so watch for subtle behavior changes. Remember that these changes can be gradual but overall different from how your child or teen has generally behaved in the past.

Signals to watch for include, but are not limited to:

- Large blocks of unexplained time that your child or teen is spending alone (in the bathroom, getting dressed, doing homework, etc.)

- Doing things again and again (repetitive behaviors)

- Constant questioning of self-judgment; excessive need for reassurance

- Simple tasks taking longer than usual

- Perpetual tardiness

- Increased concern for minor things and details

- Severe and extreme emotional reactions to small things

- Inability to sleep properly

- Staying up late to get things done

- Significant change in eating habits

- Daily life becomes a struggle

- Increased irritability and indecisiveness

People with OCD usually report that their symptoms get worse the more they are criticized or blamed because these emotions generate more anxiety. It is essential, then, that you learn to view these behaviors as signals of OCD and not as personality traits. This way, you can help your child to combat the symptoms, rather than encouraging your child to hide the symptoms out of shame or fear.

It is essential, then, that you learn to view these behaviors as signals of OCD and not as personality traits. This way, you can help your child to combat the symptoms, rather than encouraging your child to hide the symptoms out of shame or fear.

2. Modify expectations

People with OCD consistently report that change of any kind, even positive change, can be experienced as stressful. It is often during these times that OCD symptoms tend to flare up; however, you can help to moderate stress by modifying your expectations during these times of transition. Family conflict only fuels the fire and promotes symptom escalation (“Just snap out of it!’). Instead, a statement such as: “No wonder your symptoms are worse — look at the changes you are going through,” is validating, supportive, and encouraging. Remind yourself the impact of change will also change; that is, the person with OCD has survived many ups and downs, and setbacks are not permanent.

3. Remember that people get better at different rates

There is a wide variation in the severity of OCD symptoms between individuals. Remember to measure progress according to your child’s own level of functioning, not to that of others. You should encourage your child to push him/herself and to function at the highest level possible; yet, if the pressure to function “perfectly” is greater than a person’s actual ability, it creates more stress which leads to more symptoms. Just as there is a wide variation between individuals regarding the severity of their OCD symptoms, there is also wide variation in how rapidly individuals respond to treatment. Be patient. Slow, gradual improvement may be better in the end if relapses are to be prevented.

Remember to measure progress according to your child’s own level of functioning, not to that of others. You should encourage your child to push him/herself and to function at the highest level possible; yet, if the pressure to function “perfectly” is greater than a person’s actual ability, it creates more stress which leads to more symptoms. Just as there is a wide variation between individuals regarding the severity of their OCD symptoms, there is also wide variation in how rapidly individuals respond to treatment. Be patient. Slow, gradual improvement may be better in the end if relapses are to be prevented.

4. Avoid day-to-day comparisons

You might hear your child say he or she feels like they are “back at the start” during symptomatic times. Or, you might be making the mistake of comparing your child’s progress (or lack thereof) with how he/she functioned before developing OCD. It is important to look at overall changes since treatment began. Day-to-day comparisons are misleading because they don’t represent the bigger picture. When you see “slips,” a gentle reminder that “tomorrow is another day to try” can combat your child or teen’s possible desire to self-destructively label him or herself as a “failure,” “imperfect,” or “out of control,” which could result in a worsening of symptoms!

When you see “slips,” a gentle reminder that “tomorrow is another day to try” can combat your child or teen’s possible desire to self-destructively label him or herself as a “failure,” “imperfect,” or “out of control,” which could result in a worsening of symptoms!

You can make a difference with reminders of how much progress has been made since the worst episode and since beginning treatment. Consider occasionally using a rating scale to have an objective measure of progress that both you and your child can refer back to. For example, ask your child to rate his or her symptoms using a simple 1–10 rating. You can ask things such as, “How would you rate yourself when OCD was at it’s worst? When was that? How is it today? Let’s think about this again in a week.”

5. Recognize “small” improvements

People with OCD often complain that family members don’t understand what it takes to accomplish something such as cutting down a shower by five minutes or resisting asking for reassurance one more time. While these gains may seem insignificant to other family members, it is a very big step for your child. Acknowledgment of these seemingly small accomplishments is a powerful tool that encourages him or her to keep trying. This lets your child know that his or her hard work to get better is being recognized, and can be a powerful motivator.

While these gains may seem insignificant to other family members, it is a very big step for your child. Acknowledgment of these seemingly small accomplishments is a powerful tool that encourages him or her to keep trying. This lets your child know that his or her hard work to get better is being recognized, and can be a powerful motivator.

6. Create a supportive environment

The more you can avoid personal criticism, the better — remember that it is the OCD that gets on everyone’s nerves. Try to learn as much about OCD as you can. Your child still needs your encouragement and your acceptance as a person, but remember that acceptance and support does not mean ignoring the OCD behaviors. Do your best to not participate in compulsions or rituals. In an even tone of voice explain that the compulsions are symptoms of OCD and that you will not assist in carrying them out because you want him or her to resist as well. Gang up on the OCD, not on each other!

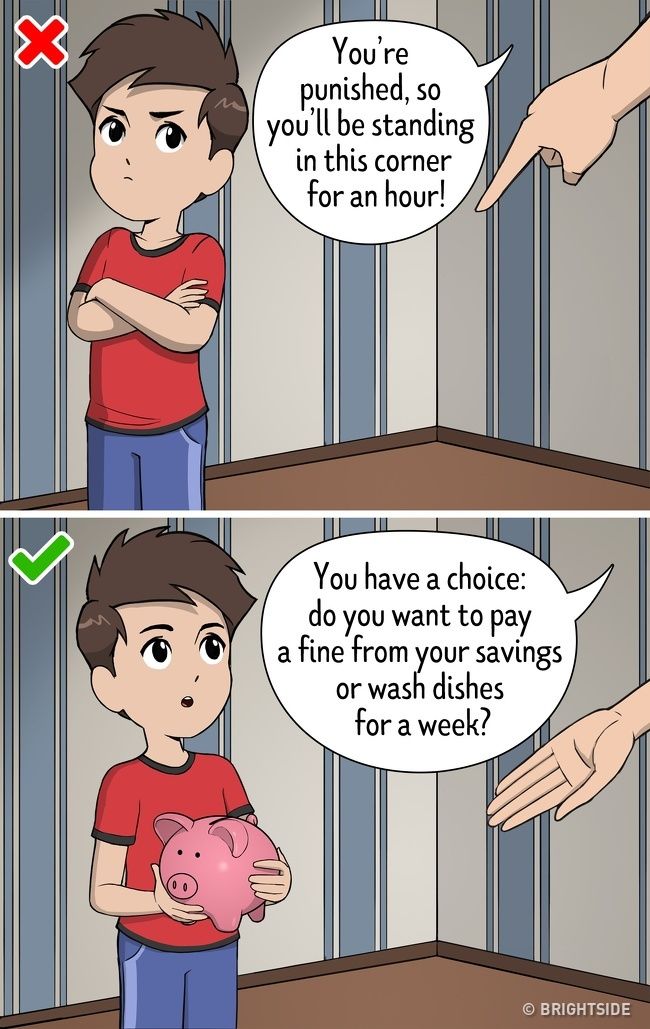

7. Set limits, but be sensitive to mood (refer to #14 below)

With the goal of working together to decrease compulsions, family members may find that they have to be firm about:

- Prior agreements regarding assisting with compulsions

- How much time is spent discussing OCD

- How much reassurance is given

- How much the compulsions infringe upon others’ lives

It is commonly reported by individuals with OCD that mood dictates the degree to which they are able to divert obsessions and resist compulsions. Likewise, family members have commented that they can tell when someone with OCD is “having a bad day.” Those are the times when family may need to “back off,” unless there is potential for a life-threatening or violent situation. On “good days” individuals should be encouraged to resist compulsions as much as possible. Limit setting works best when these expectations are discussed ahead of time and not in the middle of a conflict. It is critical to minimize family accommodation to OCD.

Likewise, family members have commented that they can tell when someone with OCD is “having a bad day.” Those are the times when family may need to “back off,” unless there is potential for a life-threatening or violent situation. On “good days” individuals should be encouraged to resist compulsions as much as possible. Limit setting works best when these expectations are discussed ahead of time and not in the middle of a conflict. It is critical to minimize family accommodation to OCD.

8. Support taking medication as prescribed

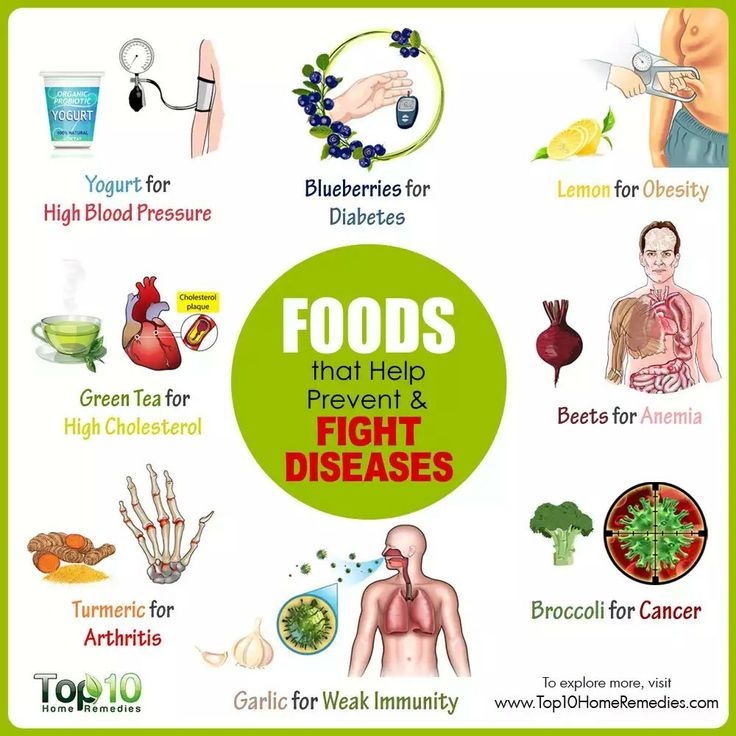

Be sure to follow the medication instructions that have been prescribed. Do not make any changes to your child’s dosage without consulting the prescribing physician. If you notice serious side effects and have concerns, tell you doctor immediately. Only trained professionals will know the implications of changing medication dosages or what might happen if medications are stopped abruptly.

9. Keep communication clear and simple

Avoid lengthy rationales and debates when your child or teen is seeking reassurance or asking for accommodation. This is often easier said than done because most people with OCD constantly ask those around them for reassurance: “Are you sure I locked the door?” or “Did I really clean well enough?” You have probably found that the more you try to prove that your child does need not worry, the more he or she disproves you. Even the most sophisticated explanations won’t work. There is always that lingering, “What if?”

This is often easier said than done because most people with OCD constantly ask those around them for reassurance: “Are you sure I locked the door?” or “Did I really clean well enough?” You have probably found that the more you try to prove that your child does need not worry, the more he or she disproves you. Even the most sophisticated explanations won’t work. There is always that lingering, “What if?”

Tolerating this uncertainty is an exposure (which your child should have learned how to manage in their ERP therapy) that may be tough for your child. Recognize that your child is triggered by doubt and label the problem as one of trying to gain total certainty about something that cannot be provided — this is the essence of OCD, and the goal is to accept uncertainty in life — and move on.

10. Separate time is important

Family members often have the natural tendency to feel like they should protect an individual with OCD by being with him or her all of the time. This can be destructive because family members need their private time, as do people with OCD — even children!

Make age-appropriate determinations about how much freedom and independence your child or teen should reasonably have, and give him/her the message that he or she can be left alone and can care for themselves sometimes. OCD cannot run everybody’s life; you have other responsibilities and interests, and your other children and your spouse likely need your attention as well. This not only keeps you and the rest of the family from resenting the OCD. It is also a example to your child or teen with OCD that there is more to life than anxiety. Again, this is a great topic to address with your child’s therapist.

OCD cannot run everybody’s life; you have other responsibilities and interests, and your other children and your spouse likely need your attention as well. This not only keeps you and the rest of the family from resenting the OCD. It is also a example to your child or teen with OCD that there is more to life than anxiety. Again, this is a great topic to address with your child’s therapist.

11. It has become all about the OCD!

Whether it is about asking and providing reassurance to the child with OCD or talking about the desperation and anxiety that the illness causes, families struggle with the challenge of engaging in conversations that are “OCD free,” an experience that feels liberating when achieved. We have found that it is often difficult for family members to stop engaging in conversations around the anxiety because it has become a habit and such a central part of their life. It is okay not to ask, ”How is your OCD today?” Some limits on talking about OCD and various worries is an important part of establishing a more normative routine. It also makes a statement that OCD is not allowed to run the household.

It also makes a statement that OCD is not allowed to run the household.

12. Keep your family routine “normal”

Often families ask how to undo all of the effects of months or years of going along with OCD symptoms and accommodations. For example, to avoid a tantrum, parents may allow their daughter’s contamination fear to dictate who can enter the home, and they may decide to prohibit their other children from inviting any friends over.

While this avoids an initial meltdown, it is also likely to create resentment and animosity, and also establishes the idea that the parents will cave to other OCD demands in the future. How do you break this cycle?

Through negotiation and limit setting, family life and routines can be preserved. Remember, it is in your child’s best interest to tolerate exposure to their fears and to be reminded of their siblings’ and other family member’s needs.

13. Be aware of family accommodation behaviors (refer to #14 below)

First, there must be an agreement between all parties that it is in everyone’s best interest for family members to not participate in rituals or accommodate OCD demands. However, in this effort to help your loved one reduce OCD behaviors, you may be easily perceived as being mean or uncompassionate, even though you are trying to be helpful. It may seem obvious that all family members and your child with OCD are working toward the common goal of symptom reduction, but the ways in which people do this varies. Attending a family educational support group for OCD or seeing a family therapist with expertise in OCD often helps improve family communication and understanding.

However, in this effort to help your loved one reduce OCD behaviors, you may be easily perceived as being mean or uncompassionate, even though you are trying to be helpful. It may seem obvious that all family members and your child with OCD are working toward the common goal of symptom reduction, but the ways in which people do this varies. Attending a family educational support group for OCD or seeing a family therapist with expertise in OCD often helps improve family communication and understanding.

14. Consider using a family contract

The primary objective of a family contract is to get all family members (including your child with OCD) to work together to develop realistic plans for managing the OCD symptoms in behavioral terms. Creating goals as a team reduces conflict, preserves the household, and provides a platform for families to begin to “take back” the household in situations where most routines and activities have been dictated by an individual’s OCD.

By improving communication and developing a greater understanding of each other’s perspectives, it is easier for your child to have family members help him or her reduce OCD symptoms instead of enable them. It is essential that all goals are clearly defined, understood, and agreed upon by any family members involved with carrying out the tasks in the contract. Families who decide to enforce rules without discussing it with the child with OCD first find that their plans tend to backfire. Some families are able to develop a contract by themselves, while most need some professional guidance and instruction. Be sure to reach out for professional assistance if you think you could benefit from it.

It is essential that all goals are clearly defined, understood, and agreed upon by any family members involved with carrying out the tasks in the contract. Families who decide to enforce rules without discussing it with the child with OCD first find that their plans tend to backfire. Some families are able to develop a contract by themselves, while most need some professional guidance and instruction. Be sure to reach out for professional assistance if you think you could benefit from it.

Adapted from guidelines developed by Barbara Livingston Van Noppen, PhD, & Michele Tortora Pato, MD, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California.

How to help a child with OCD?

Hello.

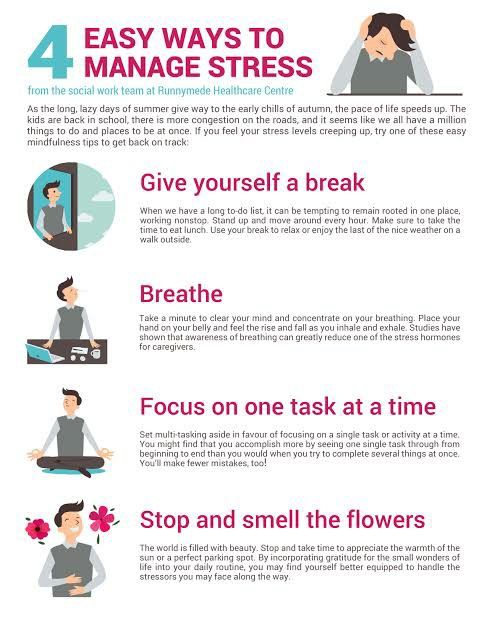

Such children, as well as their relatives, need long-term support from a psychologist or psychotherapist. The child needs to learn how to cope with emotions and tension, and you need to provide support and keep inner balance. And these are not questions of one consultation. Drug treatment can have an effect, but very briefly, if you do not connect a psychologist to the question.

Drug treatment can have an effect, but very briefly, if you do not connect a psychologist to the question.

The fact is that drugs reduce anxiety, but do not teach you to live differently. If your doctors and psychologists do not adhere to this point of view, I strongly recommend that you contact another specialist / specialists. nine0003

Your behavior strategy should be something like this: it is important to respect the feelings of the child, but not to play along with him. For example: "I can see that you're scared. I'm sorry you can't go to the park with us." Try not to recognize OCD as a disease or condition that cannot be controlled. The fact is that OCD is often in children who subconsciously want to be good. The thought is something like this: "I'm holding back with all my might, I'm trying, I'm a good child for my mother." But the psyche is looking for a way out and finds it in the symptoms of OCD. And then the child unconsciously concludes: "I'm good, it's just that OCD is a disease, and there's nothing I can do about it. " Therefore, it is important to designate all rituals and fears as decisions and choices. Obviously not blaming the child for this, but adhering to neutrality in emotions. For example: "You seem to enjoy touching this." Stick to one strategy of behavior yourself and enlist the support of all family members. Try not to connect strangers to this, even in a playful way. OCD should not affect the course of your life. You don’t need to wash your house more and more often, you don’t need to limit yourself to travel and so on. Parent Lead, Child Lead: This rule holds true for children with OCD. And of course, show respect for the feelings of the child. Do not try to call for common sense, logic and your experience. Do not make fun of or try to convince the child of the absurdity of his movements. Better name what is happening, emotions (his and yours). If a child asks you to participate in his rituals, then you can do this, but it’s better to take pauses, for example: “Yes, of course, I’ll help you now, I’ll just finish what I’m doing now.

" Therefore, it is important to designate all rituals and fears as decisions and choices. Obviously not blaming the child for this, but adhering to neutrality in emotions. For example: "You seem to enjoy touching this." Stick to one strategy of behavior yourself and enlist the support of all family members. Try not to connect strangers to this, even in a playful way. OCD should not affect the course of your life. You don’t need to wash your house more and more often, you don’t need to limit yourself to travel and so on. Parent Lead, Child Lead: This rule holds true for children with OCD. And of course, show respect for the feelings of the child. Do not try to call for common sense, logic and your experience. Do not make fun of or try to convince the child of the absurdity of his movements. Better name what is happening, emotions (his and yours). If a child asks you to participate in his rituals, then you can do this, but it’s better to take pauses, for example: “Yes, of course, I’ll help you now, I’ll just finish what I’m doing now. ” At first, you can take 1-3 minutes. Then it is worth increasing the interval. Also, you can very enthusiastically watch the rituals of the child (without pity and depreciation), and then, if the child asks to connect, you can do as you please. If he asks you to do it the way you "should" you can correct yourself with the words: "Oh, yes, you don't love the way I like it." All your actions should be aimed at recognizing what is happening, but this is all the way the child wants, and not the way it "should be" or "should be done." If the condition is accompanied by panic attacks, then it is worth learning the "square" breathing technique. This is a breath for 4 seconds, then a pause for 4 seconds, then an exhalation for 4 seconds and again a pause for 4 seconds. And so at least 10 times. Return sensations in the body: a hand on the back (the area between the shoulder blades), hugs, or just hold the hand. And be sure to monitor your psychological state. Monitor the quality and quantity of sleep, nutrition and satisfaction of needs.

” At first, you can take 1-3 minutes. Then it is worth increasing the interval. Also, you can very enthusiastically watch the rituals of the child (without pity and depreciation), and then, if the child asks to connect, you can do as you please. If he asks you to do it the way you "should" you can correct yourself with the words: "Oh, yes, you don't love the way I like it." All your actions should be aimed at recognizing what is happening, but this is all the way the child wants, and not the way it "should be" or "should be done." If the condition is accompanied by panic attacks, then it is worth learning the "square" breathing technique. This is a breath for 4 seconds, then a pause for 4 seconds, then an exhalation for 4 seconds and again a pause for 4 seconds. And so at least 10 times. Return sensations in the body: a hand on the back (the area between the shoulder blades), hugs, or just hold the hand. And be sure to monitor your psychological state. Monitor the quality and quantity of sleep, nutrition and satisfaction of needs. The psyche needs strength, and it draws them primarily from basic needs. nine0003

The psyche needs strength, and it draws them primarily from basic needs. nine0003

Olga Dorohova,

psychologist of the site "I am a parent"

"Good" and "bad" children's rituals: what is OCD?

Family customs, habitual activities and rituals help children cope with a world that is not yet very clear, give a sense of security. But what to do when there are too many rituals and they stop working? Psychologist Anna Skavitina tells you when to pay attention to such behavior. nine0003

Anna Skavitina, psychologist, analyst, member of the IAAP (International Association of Analytical Psychology), supervisor of the ROAP and the Jung Institute (Zurich), expert of the Psychology journal

Everything in order

family life. They want to help adults bake holiday cookies or require you to go to the store with them every Friday after kindergarten and take them for a walk in the park every Saturday. Even small children are well versed in the daily, weekly and annual rhythms of family life - and strive to participate in everything. The natural family routine and consistent customs and rituals provide them with a predictable structure of life that guides and regulates behavior and creates and maintains an emotional family climate that aids early development. nine0003

The natural family routine and consistent customs and rituals provide them with a predictable structure of life that guides and regulates behavior and creates and maintains an emotional family climate that aids early development. nine0003

At the age of two or three, children are very fond of inventing their own rituals. Often these rituals accompany especially difficult moments of transition from one state to another for children. For example, it is important to do something specific before going to bed or before leaving the house on the street, before entering the building of a kindergarten or school.

Some kids need to sit all their teddy bears, hares, and dolls along the bed before bed, or park all the cars in the garage, put on some special pajamas, or read a story. If the ritual is violated for some reason, the child can throw a serious tantrum, often incomprehensible to parents, he has to be calmed down for a long time, and only after everything is done correctly, he will be able to fall asleep.

These rituals are an absolutely normal phenomenon that helps children cope with a very incomprehensible world around them, these sequences of actions show that everything is going according to plan, everything will be fine in life. nine0003

For example, a bath, story time and hugs every night, and other bedtime rituals give children a sense of security. They feel at ease; they know what to expect. Everything is as it should be. Here, rituals are an important part of a child's development. And they can be supported and even helped to create. Try to break complex things down into a sequence of simpler and more understandable ones to make them easier to master. If your going out for a walk with a child or sitting down for homework always goes according to plan, your sequence of actions is unchanged, then children will have much less objections, whims and resistance. nine0003

When rituals do not help

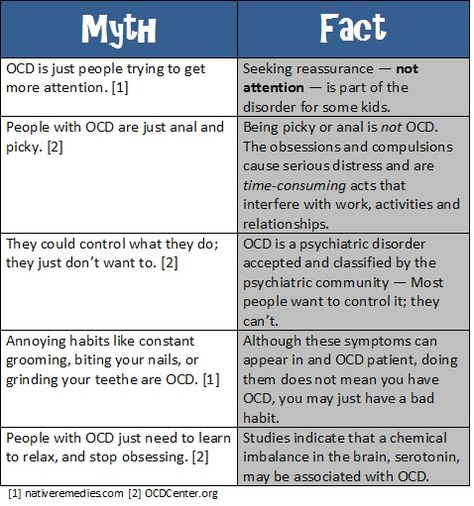

But it happens that there are so many rituals, and they are so rigid and obligatory, that even the failure to perform the rituals causes very strong anxiety and panic, and normal rituals cease to be normal, turning into a mental disorder with obsessive actions : obsessive-compulsive disorder .

How is it that something so good and helpful in one situation causes so much suffering in another? As a rule, children are calmed and comforted by invented and family rituals, while a child with obsessive-compulsive disorder experiences only fleeting calm from this. Worry and anxiety return again and again, and he feels compelled to perform the ritual again and again. nine0003

This is the hallmark of OCD: that feeling of "incompleteness" that makes sufferers perform rituals over and over again. Over time, the initial rituals seem to be insufficient, and more complex rituals need to be developed. It turns into an endless vicious circle. So, the child goes to wash his hands: they are not clean enough, and they need to be washed, and then wash the soap itself or the bottle of soap, and then wash the towel with which he wiped his hands to finally remove the invisible dirt that seems to be able to penetrate inside - and from you can get sick and even die. nine0003

I don't remember!

All people have moments similar to such a disorder: for example, when you forget if you locked the door and have to go back and check if you locked it correctly, and when you move away from the door, you start to worry that you didn’t check well, you closed her one lock or two. And then all of a sudden you think you might have left the iron or stove on, and you come back to check if it's true. If this does not happen to you often, then everything is in order. Perhaps on this particular day you are more worried about something than usual, and your head is so busy with these thoughts that your attention is not enough to notice the usual automatic actions, and your consciousness does not fix whether you have done simple and understandable actions such as open / close the door. nine0003

And then all of a sudden you think you might have left the iron or stove on, and you come back to check if it's true. If this does not happen to you often, then everything is in order. Perhaps on this particular day you are more worried about something than usual, and your head is so busy with these thoughts that your attention is not enough to notice the usual automatic actions, and your consciousness does not fix whether you have done simple and understandable actions such as open / close the door. nine0003

Most likely, at these moments you are worried about some situations related to your lack of security, and just in case, your head starts to additionally turn on the signal system of checking “Is the world really safe?” and direct it to everything around.

By the way, to stop running to the door and checking the locks, after you have closed the door of the apartment or car, it is enough to say clearly aloud: “I closed (a) the door!” Your voice will become a fixation of consciousness on an action that usually happens automatically without your participation.

nine0003

This is important to know

— Between the usual childhood rituals, cleaning up the house, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, there is a whole range of different conditions that are not disorders, and can both help us live and interfere - such as checking whether we are closed doors. As long as the obsessions do not interfere with you or the child's life, nothing special can be done.

— Often the parents of children with obsessions are themselves very anxious and have their own obsessions that they do not always notice. They want to be very good parents and do everything right, so they develop fairly clear rules for raising and caring for a child, based on the theories and ideas they have learned, sometimes ignoring the individuality and desires of the child himself. nine0003

— Children of anxious parents, on the one hand, feel that they are taken care of, that their parents want the best for them, but at the same time they feel that they cannot do what they want, as if they are betraying themselves.

— It seems to children that they are not praised enough, but they are controlled and punished a lot if they do something of their own, and not what their parents want from him.

- Anxious parents allow themselves to show aggression only in the form of stubbornness and rigidity, and children adopt this model from them. The family often pretends that there is no aggression when it actually is, which disorients the child, not allowing him to trust his feelings. Aggression is perceived as something forbidden, and as soon as it appears, the child tries to “hide” it behind certain actions: if I jump over cracks on the asphalt, then my mother will not swear at me. nine0003

If you're wondering if your child has OCD, you might notice if the rituals calm him down for more than a few minutes, or if the rituals need to be repeated over and over again. It's also a good idea to pay attention to the amount of time a child spends on rituals, as well as how much it interferes with his daily life.

As a general rule, if you spend an hour or more a day performing special rituals, this should raise certain questions. nine0003

— Diagnosing this disorder in young children is not always easy, as it can present in many ways. Normally, when a child grows up, he begins to care less and less about the arrangement of his plush friends when falling asleep. On the other hand, it happens that children who did not have any special play rituals at an early age can also develop OCD.

As parents, we need to know that OCD often starts in childhood. I can't tell you how many times people have said to me, "For as long as I can remember, I've always had these symptoms." Therefore, the sooner OCD is diagnosed and the correct therapy is prescribed, the less likely it is that the disorder will get out of control. If you suspect for any reason that your child is suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder, I would advise you to consult a psychiatrist who will conduct a proper examination.