How hard is it to adopt a child in australia

how hard is it to adopt in Australia?

When politicians and lobbyists call for adoption reform in Australia, they often argue adoption should be easier and quicker. Adopting a child in Australia can be difficult, but whether barriers to adoption are always a bad thing is up for debate.

The numbers

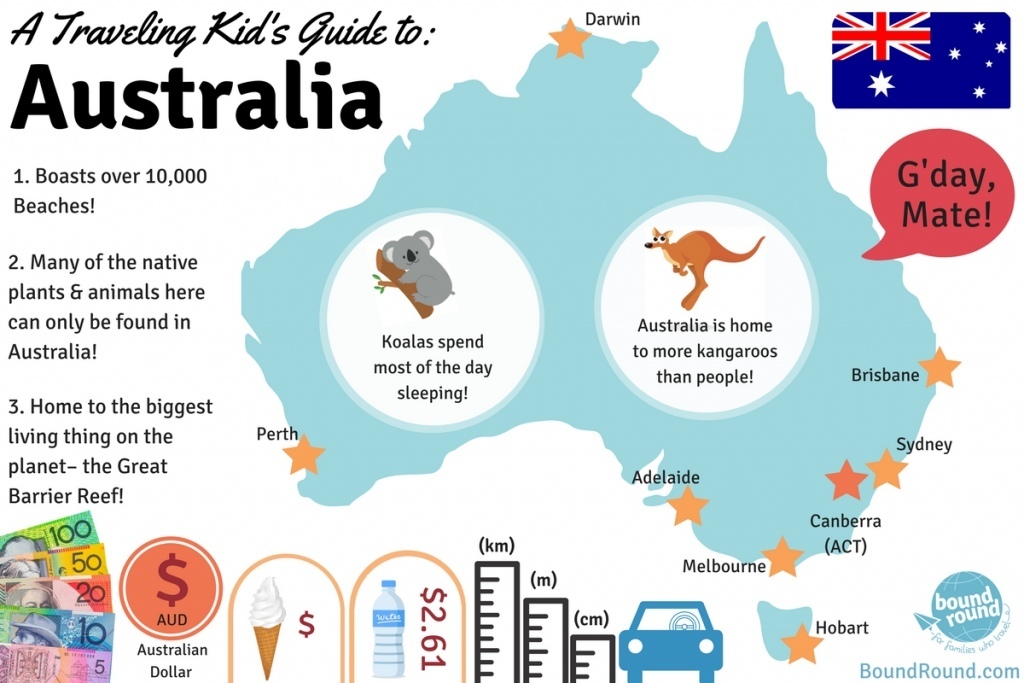

Local and intercountry adoptions are the two main types of adoption in Australia.

The federal government is the central authority for intercountry adoptions, ensuring Australia complies with the Hague Convention on intercountry adoption and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child. States have responsibility for all adoption services.

The wait for intercountry adoptions depends on the country, and takes between three and five years. Of the 315 adoptions finalised in Australia in 2016-17, 69 were adoptions from Asian countries such as Taiwan, the Philippines and South Korea. The majority of children were under five years of age.

There are no waiting time statistics available for local adoptions, but we do know that 42 local adoptions were finalised in 2016-17. Most local adoptions were of babies, maintaining the trend for young children.

Same-sex couples can now adopt locally in every state and territory in Australia, with the Northern Territory parliament legalising same-sex adoptions last month. Single people can adopt in most states. For intercountry adoptions, the country of birth determines who can adopt.

In all adoptions, there is no guarantee that an adoption will take place. Sending countries can close or change their quotas or establish family preservation and domestic adoption programs.

In local adoption, the prospective parents or parent who can best meet the needs of a particular child should be matched. The child’s family should also be comfortable with the decision.

Are other countries doing better?

Policy directions in Australia have not changed since under the Abbott government, which promised to simplify adoptions, was ousted.

Lobbyists like actress Deborra-Lee Furness are still exercising influence to make adoption easier, albeit less in the public eye, and the attention has shifted from intercountry adoption to local adoptions.

Lobbyists lean towards the UK local adoption system and US approach to intercountry adoptions, where adoption services are delivered in the private market. But the English system is badly in need of reform, after years of policymakers promoting adoption as “risk-free in a happy ever after narrative”.

The US is also reforming its very broken system. It has been criticised for incidents of trafficking, child deaths, and rehoming, in which adopted children have been offered to strangers over the internet.

Countries that report higher numbers of adoptions deal with countries that Australia does not – including countries that have not signed the Hague Convention. Among these, the US and Spain estimate high numbers of adoption breakdowns (“disruptions” are short term and “dissolutions” are complete breakdowns).

Most children made available for local and intercountry adoption have families. Adptions that are non-Hague and facilitated in countries that have limited capacity to properly assess a child’s circumstances, and where corruption is rife, are open invitations to illegal and unethical adoptions.

Anecdotally, most adoptions in Australia are successful, but we do not know the true rate of breakdowns. Families are only followed up for one year after an adoption. But we do know there is insufficient support for families, foster families, adoptive families and adoptees.

Tony Abbott addresses a morning tea for National Adoption Awareness Week in 2013. Jane Dempster/AAPAdoption is hard for a reason

I have written before about the dangers of adoption-driven systems, in which success is counted in numbers. Adoptions do become easier and faster, but safeguards are reduced. The consequences for children, first families and adoptive families can be lifelong.

Adoptions are hard for good reasons. A sound, ethical process is necessary to ensure a child is legally and ethically available for adoption, consents are free from coercion, and parents are given adequate time to change their minds.

While Australia is bound by international conventions that protect human rights and those of children, there is no right to parent: children are the rights holders in adoption processes. Prospective parents must undergo preparation and assessment on their capacity to meet all the needs of an adopted child to uphold children’s basic rights.

Prospective parents must undergo preparation and assessment on their capacity to meet all the needs of an adopted child to uphold children’s basic rights.

Support for family preservation and culturally appropriate placements should always be explored. In recent years, the importance of culture and identity, especially for Indigenous Australians, has been undermined in political rhetoric.

Adoption generally has become synonymous with child protection. Child protection measures are actually interventions such as prevention, monitoring or child removal, which occur well before an adoption takes place.

Consistent with global trends, intercountry adoptions in Australia are declining. This is due to compliance with international conventions to reduce illegal and unethical adoptions and the development of local adoption programs.

Read more: International adoptions have dropped 72 percent since 2005 – here’s why

Outcomes for children

Support that enables children to stay with their families and within their culture is a positive outcome.

The number of adoptions in Australia is small because not all children separated from their families need adoption, so moral panic and distorted claims about the welfare of children should be resisted.

Adoption is a service for children. It is not a service for people to make families – a subtle and important difference. A “hard” adoption process should be embraced, even if it takes a little longer. Making sure adoptions are both legal and ethical is better for everyone, especially the children.

What is the adoption process in Australia and why don't more children get adopted?

Asking people who want kids why they don't "just adopt" is a common refrain but actual adoption in Australia isn't all that common.

Just 334 adoptions were finalised in 2019-20.

So why don't more adoptions happen and what's really involved in the process?

There are a few reasons for this and we have to look at the three types of adoption to understand why.

Local adoption is probably what you think of when you hear the word "adoption". This is the adoption of children not known to their adoptive parents.

Known-child adoption means the child is already known to their adoptive parents (think foster carers or relatives).

And then there's intercountry adoption, i.e.the adoption of children from overseas.

Known-child adoptions are rising but the other two are going down.

Intercountry adoption has decreased since the 1990s because of ethical concerns. To give you a sense of how few of these happen, only 37 intercountry adoptions were finalised in 2019-20.

"And local adoption has declined because we live in a different culture now compared to when there was forced adoption," explains Renee Carter, chief executive of Adopt Change.

"There isn't the stigma that used to exist around being a single mother. There aren't as many people choosing to place a child into adoption."

Just 48 local adoptions were completed in 2019-20.

"Meanwhile, a number of states have been introducing legislation so that there's a timeframe of two years for having permanency plans, such as adoption, in place for children in care who can't return home," Ms Carter says.

"So there's been an increase in [known-child adoption because] carers who have had kids in their care for years [have been] formalising that through adoption."

The laws and requirements around adoption and who's allowed to adopt vary across Australia and based on adoption type.

If you'd like specific information tailored to your state or territory, check out the relevant government websites below:

- Victoria

- New South Wales

- Australian Capital Territory

- Queensland

- Northern Territory

- Western Australia

- Tasmania

- South Australia

Generally speaking, a prospective adoptive parent needs to be an adult who is "available and able to provide for the child until they turn 18," says Kay Berry, Barnardos Australia's head of adoptions.

This means they need to be in reasonable health, and must undergo police and working with children checks.

Upper age limits are generally less of a barrier these days; in 2019-20, 44 per cent of local adoptive parents were 40 and over.

"And it's even higher for known-child adoptions, so that is a shift, even looking back a few years ago," Ms Carter says.

But if you're looking at intercountry adoptions, age limits for prospective adoptive parents vary depending on the country you're looking to adopt from.

The acceptance of single adoptive parents depends on the place you're adopting from and on the individual case. This applies to both intercountry adoptions and adoptions from within Australia.

Before you begin the actual application process, experts say you should think about your motivation for adopting.

"This comes in all different forms, but a key part should be about helping a child in need because these are very vulnerable children," Ms Berry says.

Another big thing to consider is that Australia now practices open adoption, which means birth family contact is expected throughout children's lives. You'd need to be confident and comfortable with facilitating that.

Adoption is "open" in Australia, which means birth family contact is expected until the child turns 18. (Adobe Stock: conceptualmotion)Any child who comes into your care will have a history, and all children have different needs, though there are obvious differences between bringing a baby home versus an older child.

If you're adopting an infant, the expectation is generally that there will be a full-time carer at home for a certain time period, Ms Carter explains.

"Sometimes it suits prospective parents who need to keep working to have school-aged kids, and we have a huge need for homes for older children," she says.

If you think this could be right for you, Ms Berry says you should also be prepared for the fact that "older children often have more needs".

"Many have been in situations of domestic violence, many have delayed development and require specialist interventions … some children may have NDIS care plans."

And if you want to adopt a child with a different cultural background to you, Ms Berry says you need to be prepared to actively integrate their culture into your daily life.

"Involved" is the word Ms Berry lands on to describe the adoption application process.

"It can be quite an exposing thing because many people get to hear more about your lives than would normally be shared," she says.

Exactly how "involved" the process is depends on the pathway and adoption type you're considering.

The local and known-child adoption processes generally involve getting in touch with your relevant state department or an accredited adoption agency after doing your research.

Next come the information sessions, assessment and training (if you'd like more information on this, this NSW-specific website outlines this part of the process generally).

"The assessment part includes things like medical interviews and home checks," Ms Carter says.

Then, you wait to be matched. (More on how long this can take below.)

That's followed by placement and post-adoptive/placement support. Finally, the adoption is approved by the court in your jurisdiction.

There are heaps of variables for intercountry adoptions. For a better understanding of this process and the concerns that come with it, start with this official government website.

But generally, people looking to adopt children from overseas must meet the eligibility criteria of the state or territory they live in, as well as that of the partner country, go through a similar assessment and training process and finally be approved by a state or territory central authority, or meet immigration requirements.

Be a part of the ABC Everyday community by joining our Facebook group.

The question of how long it takes is another difficult one to answer beyond "it depends".

But there are some general guides.

The median wait time for intercountry adoption is just under three years.

"And local adoption can take less time," Ms Carter says.

"With known adoptions, often the carer has had that child in their care already, but it still usually takes at least a couple of years [to complete].

"If you put your hand up for foster care, within a year that you start the process and go through authorisation, you can have a child in your home."

This article contains general information only. Refer to your local government for details around laws and requirements regarding adoption.

ABC Everyday in your inbox

Get our newsletter for the best of ABC Everyday each week

Posted , updated

Australia: Features of national adoption | RefNews

Rethinking contemporary and historical adoption experiences will help thousands of children in foster care, says a new report from Australian experts.

Australia is known as the Land of the Lucky, but the almost 40,000 children in orphanages waiting for a permanent home with loving parents and the many spouses who want to adopt a child are hardly lucky.

Adoptions in Australia have declined by a staggering 9 over the past 40 years7%: with almost 10,000 adoptions in 1971-72 to just 339 in 2012-13, with almost a third of them made overseas. Other countries also experienced a decline in adoptions, albeit not much compared to Australia.

Are we really taking better care of children in need? Or is the fact that a large number of them are in shelters a sign that we have preferred ideological and bureaucratic concerns to their interests? A new report from the Australian Women's Forum "Adoption Rethink" shows that the latter is closer to the truth.

The report examines the decline in adoptions from various perspectives, including the current rise in legal abortions, feminist theory and media coverage. It tracks how this practice, once seen as a natural and obvious solution to the needs of children who are unable to be raised by their own parents, has fallen out of favor in recent decades, and how it affects the growing number of children being raised outside the family.

Closed adoptions, stolen generations

At the forefront of this recent story are women who abandoned their children at birth in a time when single mothers were viewed with disapproval. Sometimes these women were under pressure to give up babies without knowing the adoptive parents or expecting to ever see their child again. These women speak of their grief and the wound they have received. Already grown children, who were adopted / adopted under the same “closed” regime, also complained about their painful “quest” to find their biological parents, their full identity. Studies conducted among such people revealed a high level of mental disorders in them.

These women speak of their grief and the wound they have received. Already grown children, who were adopted / adopted under the same “closed” regime, also complained about their painful “quest” to find their biological parents, their full identity. Studies conducted among such people revealed a high level of mental disorders in them.

Historical errors that lead us to speak of the Stolen Generations (separating Aboriginal children from their families), lost innocents (the "export" of 7,000 children from the UK in the early 20th century) and Lost Australians (hundreds of thousands of Australians who spent their childhoods in orphanages) have also contributed to the bleak notion of adoption over the past ten years.

At the same time, the population of children who could benefit from adoption has also changed. Early 19In the 1970s, at least half of the adoptions involved the children of young unmarried women. They, themselves almost children, were encouraged, even forced to give away a child they could not raise alone, and instead encouraged to strive to complete their education, find a job and get married. Now those norms have changed with benefits, abortions and birth control pills.

Now those norms have changed with benefits, abortions and birth control pills.

Is another lost generation on the way?

Today's picture is very different from the past. Most children in Australia (and similar countries) in need of foster parents have been taken from their biological parents due to physical, sexual or emotional abuse, neglect, and placed in foster homes. The number of these children has doubled over the past decade, however, despite this, it takes an average of four years to adopt a child into a foster family.

At a time when dramas about foreign adoptions fill the pages of magazines and newspapers, the uncertain future of these children is a growing scandal that calls for urgent action.

Rethinking Adoption reports that of 39,621 children in foster care in mid-2012, two out of three were in a state of permanent family-to-family transfer for two or more years, with an increasing number of children continually returning to the system . “Thus, children in foster care live in a state of more frequent change and instability, which leads to more complex needs and behaviors.”

“Thus, children in foster care live in a state of more frequent change and instability, which leads to more complex needs and behaviors.”

Becky Hope, in her book All In a Day's Work, cited in the report, emphasizes the critical importance of stable, loving care during the earliest periods of a child's life:

who do not get their basic needs met in reciprocal, loving care, and who are forced to scramble through life on their own, suffer visible devastating effects of brain development even before they are a year old.

It has also been found that children who experience severe lack of parental attention as infants and are placed in long-term foster care before six months of age are able to generally make more progress than if they are adopted after six months.

Children need stability to form secure attachments, but guardianship, no matter how well it is done, is temporary in nature. While there has been an increase in permanent guardianship cases in Australia (and similar instruments elsewhere), a recent study in Queensland found that such arrangements "do not provide enough stability for children". On the one hand, the rights of guardians can be challenged by the family of origin, on the other hand, they do not give children the same sense of belonging to the family, unlike adoption.

On the one hand, the rights of guardians can be challenged by the family of origin, on the other hand, they do not give children the same sense of belonging to the family, unlike adoption.

Gregory Pike, director of the Center for Bioethics and Culture in Adelaide, also comments on this situation in the report “Rethinking Adoption”: adoptions. The cost to society and government of caring for these children and treating the traumatic consequences of their situation is enormous.

Adoption: open and closed

(Ed. With a closed adoption, the adoptive family can keep the fact that the child is not a parent, with an open adoption is not a priority)

In Australia in 2011-12, 95% of local adoptions were open - this is a continuing upward trend that has covered 80% of adoptions since 1998.

Although some adoptions did not really take into account the needs of the birth mothers (fathers were usually not in this picture at all) and the child, in the age of open adoptions, every effort is made to respect the rights and feelings of all participants in the “adoption triangle” . In any case, it is the adoptive parents who now suffer their own stigma for being on a side with a dark history, which has negatively impacted a significant number of people.

In any case, it is the adoptive parents who now suffer their own stigma for being on a side with a dark history, which has negatively impacted a significant number of people.

There is a tendency to exaggerate this influence.

Dr. Pike reviewed local and international reports on adoption outcomes for biological mothers, adopted children and parents, including those who belonged to the "closed" age. The literature provides a much more detailed picture than is evident from media reports of people who have gone through negative or unhappy experiences.

Undoubtedly, some mothers who were forced to give up children suffered, but “a significant amount of uncertainty exists about how common these outcomes were and how they relate to the characteristics of adoption and its process,” Pike says. There is evidence that finding and reuniting with a child has a healing effect.

Looking at the problems of adopted children, he found the following: Although adopted children represent the largest proportion of patients with mental disorders, the actual proportion of "adoptees" in a society with such problems is very small. Foster children face significant challenges in addition to those typically experienced by children in early childhood and adolescence, however, there is evidence that foster children have incredible resilience and there is official evidence of their ability to "catch up" on various occasions. For some adopted children, their experiences prior to adoption were often difficult and sometimes traumatic, and these experiences were associated with later outcomes. When compared with their peers who remained in the shelters, the "adoptees" had better physical and mental health and better circumstances in education and socialization. The key issues for adopted children were attachment, self-determination, search and recovery.

Foster children face significant challenges in addition to those typically experienced by children in early childhood and adolescence, however, there is evidence that foster children have incredible resilience and there is official evidence of their ability to "catch up" on various occasions. For some adopted children, their experiences prior to adoption were often difficult and sometimes traumatic, and these experiences were associated with later outcomes. When compared with their peers who remained in the shelters, the "adoptees" had better physical and mental health and better circumstances in education and socialization. The key issues for adopted children were attachment, self-determination, search and recovery.

Little research has been done on foster parents and their problems.

Intercountry adoption

Despite the bad reputation and availability of reproductive technology, it appears that many couples would be happy to adopt if given the option. Frustrated by the barriers to adoption in Australia, they often turn to orphanages in developing countries. Here again they have to wait up to five years.

Frustrated by the barriers to adoption in Australia, they often turn to orphanages in developing countries. Here again they have to wait up to five years.

Obviously, special care must be taken to ensure that the adoption of a child in another country and culture serves his best interests. Pike says: “In the case of all adoptions, and according to the Hague Convention on Adoption, cross-country adoption should be used only in cases where the biological parents (parent) or relatives do not have the ability or desire to properly care for the child. Only if there are no suitable facilities available to provide ongoing care in the State where the child was born, should ethical inter-country adoption be considered in the best interests of the child.”

Tony Abbot's government in Australia has taken steps to expedite these adoptions by creating a new national agency that will be operational by mid-2015 to negotiate adoptions with most countries.

However, each country has its own special obligations to its children, and those under the care of the state deserve a new plan. Barnados Australia, a leading non-governmental agency for the protection of child survivors of abuse, urges Abbott to set a goal for open adoptions in every state.

Barnados Australia, a leading non-governmental agency for the protection of child survivors of abuse, urges Abbott to set a goal for open adoptions in every state.

So why delay?

According to a report by Martin Nary, UK Government Adoption Adviser, important factors include: take him to meetings with his parent or parents while the court decides the future of the child. This represents a shocking mistake with devastating consequences for children and society that will last for decades."

- Parents are given priority: the needs of the parents, not the rights of the children, are the priority.

-Loss of sense of urgency when a child is placed in care.

-Social workers: the need for a balance of social workers who have maturity (not necessarily skill level) and experience in the care and development of children and young workers who may be qualified. Everyone needs to be trained in a real child protection situation and taught to understand the priorities of the child, the need to act immediately, and so on.

Pike also noted that ideology plays a key role: there are a number of references in Australian sources to an anti-adoptive mentality in some educational institutions "and perhaps among professionals who are key intermediaries", such as employees of government welfare departments. A 2005 government report on foreign adoption noted that attitudes in these departments ranged from "indifference to hostility".

Feminist ideas about patriarchy and its "dominant prescriptions" are also included. Combined with revelations about previous scandals and forced adoptions, this has shaped public opinion that children should not be separated from their parents.

This is basically a reasonable principle: the child must be with the parents and reasonable steps must be taken to ensure that they can stay together. However, when a child is neglected or abused, despite the help of relatives and the intervention of the authorities, there must come a time when the best interests of the child dictate the need for his removal from the family. At this point, undoubtedly, efforts should be focused on providing the child with a loving, stable and permanent family.

At this point, undoubtedly, efforts should be focused on providing the child with a loving, stable and permanent family.

Presumably, the principles of open adoption should apply if there is safety for the child and permission from the adoptive parents. Biological parents cannot be completely written off.

However, this should not be done with adoption either. As Pike says in the conclusion, “There is something about most adoptions that helps them end well. Despite all the complexities and shortcomings of the human experience, the mistakes of the past and the failures of the present, adoption remains a realistic and workable solution.”

Author: Carolyn Moynihan

Source: MercatorNet

Tags: australiaNo orphansadoption

"If you want to win the people, raise their children." How a ban on adoption for “unfriendly countries” may affect Ukrainian children brought to Russia

“If you want to win the people, raise their children.” How a ban on adoption for "unfriendly countries" can affect Ukrainian children taken to RussiaAlla Konstantinova

August 5, 2022, 20:38

Texts

Temporary accommodation for refugees in the village of Bezymennoe, DPR. Photo: Mikhail Tereshchenko / TASS

Photo: Mikhail Tereshchenko / TASS

On August 1, the State Duma received a bill banning adoption and guardianship for citizens of “unfriendly countries” for consideration. Perhaps it will affect not only Russian orphans, but also hundreds of thousands of children who were taken to Russia from Ukraine during the war: it seems that if the amendments are adopted, Ukrainians will not be able to adopt them.

The Russian government maintains two lists of “unfriendly countries” at once: the first one has existed since 2021 and involves restrictions on foreign embassies. Initially, it included only the Czech Republic and the United States. Greece, Denmark, Slovenia, Croatia and Slovakia were added in July 2022.

The second list appeared in March 2022 as a response to sanctions due to the invasion of Ukraine. Then the government, by decree of Vladimir Putin, approved the second list of states "committing unfriendly actions against the Russian Federation, Russian legal entities and individuals. " The document was published on the government website.

" The document was published on the government website.

This list includes 48 countries: Australia, Albania, Andorra, Great Britain, Iceland, Canada, Liechtenstein, Micronesia, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, Korea, San Marino, North Macedonia, Singapore, USA, Taiwan, Ukraine, Montenegro , Switzerland, Japan, as well as all 27 countries of the European Union.

Amendments to the articles of the Family Code prohibiting adoption by citizens of countries from the second list were made by five deputies: Leonid Slutsky and actor Dmitry Pevtsov from the Liberal Democratic Party, communist Nina Ostanina, Yana Lantratova from Just Russia and Boris Chernyshov from New People.

“For many years, the 'collective West' has been replacing the concepts of good and evil, destroying traditional family foundations and moral values,” the explanatory note to the bill says. “If you want to defeat the people, raise their children.” Transferring our children to be raised in "unfriendly countries" is a blow to the future of the nation. "

"

The share of foreign adoption in Russia is decreasing every year, while “in Russia more and more citizens are making this conscious choice,” deputies are sure. According to them, in 2021, 69 children left for foreign adoptive parents.Russian orphans, while in 2010, before the adoption of "Dima Yakovlev's law" - 3,355.

“All the children who were to be adopted by the Americans were placed in families of Russian citizens. Opponents’ attacks that foreign citizens save our orphans and mainly adopt disabled children are not supported by statistics,” the document says.

“The shed burned down – burn down the hut”

The Ombudsman for Children of Karelia Gennady Saraev says that there is “common sense” in the proposals of the State Duma deputies and he generally approves the initiative.

“From the point of view of increasing the resource capacity of the nation, this is probably the right approach,” he argues. “Children born in Russia should stay in Russia. ”

”

At the same time, Saraev believes that, while prohibiting adoption by foreigners, the state should at the same time more actively support foster families within the country.

“Here I only support the policy of the state when we put the family as the main value and the main priority. But then the question arises: how can we provide this in our native state with social support measures? The specialists that children need? These are psychologists, correctional teachers or those people who help children with not the easiest fate and sometimes heredity. There is an attempt to designate values - the fact that they began to be prescribed is already good. The main thing is not to stop there,” says the children’s ombudsman.

Anton Rubin, foster father and head of the Domik Detstva charitable foundation, admits that he is “scared when the state begins to strengthen something,” even when it comes to support measures.

“When the “Dima Yakovlev law” or the so-called “anti-orphan” law was adopted, there were also a lot of words about support, about the fact that we ourselves have a mustache, he recalls. - Indeed, then, on the emotional wave of propaganda, the number of families wishing to take a child from an orphanage sharply increased. But the problem is that these emotional outbursts never end well - and after a sharp surge in acceptance into the family, there was a surge in returns to orphanages.

- Indeed, then, on the emotional wave of propaganda, the number of families wishing to take a child from an orphanage sharply increased. But the problem is that these emotional outbursts never end well - and after a sharp surge in acceptance into the family, there was a surge in returns to orphanages.

Agitation and financial incentives for foster families will only harm children, Rubin is sure.

“Well, let's give a lot of money - and they will take children for the sake of money, and then return them in the same way,” he says. - This has already happened when they began to pay serious lump-sum compensations to families taking children with disabilities. After some time, they returned the children, but there was no mechanism for the return of compensation. So it was a very good business."

Rubin is not surprised by the ban on adoption for citizens from "unfriendly countries" and believes that Russia is now acting on the principle of "burn down the barn - burn down and hut. "

"

“Foreign adoptions have already been effectively suspended, and for a long time already,” he explains. - In recent years, the numbers of foreign adoptions have been miserable. And they are not like that because the Russians cope or we no longer have orphans - we have more than 45,000 orphans. And it seems that the Russians are in no hurry to take them. Because the most difficult remained: teenagers, children with disabilities and siblings.”

“We will not allow them to become “displaced persons””

In mid-June, the head of the National Defense Control Center Mikhail Mizintsev reported that since the beginning of the war, more than 307,000 children had been taken to Russia from Ukraine and the self-proclaimed DPR and LPR. The Ukrainian side insists that this is not an evacuation, but mass abductions. Advisor to the mayor of Mariupol, Petr Andryushchenko, wrote about 540 children from the Donetsk region, who, according to his information, are in the Romashka sports and recreation complex near Taganrog in the Rostov region. “Now children are being prepared for a simplified procedure for granting Russian citizenship,” Andryushchenko argued.

“Now children are being prepared for a simplified procedure for granting Russian citizenship,” Andryushchenko argued.

Verstka has talked to Romashka employees, who confirmed that there are “evacuated” boarding school students in the complex. But what cities these children are from, the publication did not answer.

In the last post on VKontakte, the Commissioner for Children's Rights of Karelia, Gennady Saraev, spoke about visiting temporary accommodation centers. According to him, out of 430 refugees who ended up in Karelia, 97 are children. The Ombudsman assures that they all arrived together with their legal representatives, so there is no need to look for foster families.

“If it happened that a child without a legal representative ended up in Russia – by some miracle – then the guardianship authorities should place him in a foster family, but this is only if such a child is identified,” he says.

Ukrainians come to Karelia "not just like that, but by acquaintance" - such a conclusion the Ombudsman, according to him, made from conversations with IDPs and their children.

“How did he [the child] end up in Russia?! Nobody is forcibly taking anyone anywhere. We are not so much already ... animals, yes, to steal children! Saraev laughs.

At the same time, children from the DPR and LPR in Russia, he believes, can already be placed in foster families - this issue is regulated by interstate agreements. Saraev assured Mediazona that they had already been concluded; in April, Rossiyskaya Gazeta reported that Russia and the self-proclaimed republics had only just begun agreeing on roadmaps for preparing such agreements. Saraev did not predict what awaits orphans with Ukrainian citizenship in Russia, since "it is difficult to say what will happen next."

Anton Rubin recalls that in 2000 Russia signed (but never ratified) the “Convention for the Protection of Children and Cooperation with regard to Foreign Adoption” in The Hague, which prohibits the adoption of children from a country whose authorities object to this.

“Adoption only takes place if the competent authorities of the State of origin have determined that the child is eligible for adoption,” says Rubin. “Obviously, the Ukrainian authorities have not established that these children can be adopted.”

“Obviously, the Ukrainian authorities have not established that these children can be adopted.”

He admits that in Russia they will be allowed to adopt children from Ukraine; Perhaps for this they will be issued Russian citizenship, suggests Rubin.

“It seems to me that no one will bother with the lack of Russian citizenship… Well, it will be necessary - they will extradite him,” says Rubin. - Now they are not stopped by the lack of Russian citizenship. In fact, Russia has long ceased to comply with all international treaties and conventions.”

Yana Lantratova, co-author of the draft law banning adoption for “unfriendly countries”, in response to a request for a conversation, sent the following message to a Mediazona correspondent: “Children are our national treasure, and we will not allow them to be made “displaced persons” in unfriendly countries” . At the same time, the Mediazone deputy did not answer the question whether the Family Code will apply to children displaced from Ukraine to Russia.