How does obesity affect child development

Childhood obesity: causes and consequences

1. Popkin BM, Doak CM. The obesity epidemic is a worldwide phenomenon. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:106–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Gupta RK. Nutrition and the Diseases of Lifestyle. In: Bhalwar RJ, editor. Text Book of Public health and Community Medicine. 1st ed. Pune: Department of community medicine AFMC, New Delhi: Pune in Collaboration with WHO India Office; 2009. p. 1199. [Google Scholar]

3. Bhave S, Bavdekar A, Otiv M. IAP National Task Force for Childhood, Prevention of Adult Diseases: Childhood Obesity. IAP National Task Force for Childhood Prevention of Adult Diseases: Childhood Obesity. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:559–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Raj M, Sundaram KR, Paul M, Deepa AS, Kumar RK. Obesity in Indian children: Time trends and relationship with hypertension. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:288–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Laxmaiah A, Nagalla B, Vijayaraghavan K, Nair M. Factors affecting prevalence of overweight among 12 to 17 year old urban adolescents in Hyderabad, India. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1384–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Subramanyam V, R,J, Rafi M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in affluent adolescent girls in Chennai in 1981 and 1998. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:332–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Chhatwal J, Verma M, Riar SK. Obesity among pre-adolescent and adolescents of a developing country (India) Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13:231–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV. Prevalence of obesity in affluent school boys in Pune. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:857–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Panjikkaran ST, Kumari K. Augmenting BMI and Waist-Height Ratio for establishing more efficient obesity percentiles among school children. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:135–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Williams DP, Going SB, Lohman TG, Harsha DW, Srinivasan SR, Webber LS, et al. Body fatness and risk for elevated blood-pressure, total cholesterol, and serum-lipoprotein ratios in children and adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Public Health. 1992;82:527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden C. Weight-for-stature compared with body mass index-for-age growth charts for the United States from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:761–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Himes JH, Dietz WH. Guidelines for overweight in adolescent preventive services - Recommendations from an Expert Committee. The Expert Committee on Clinical Guidelines for Overweight in Adolescent Preventive Services. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:307–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Ghosh A. Explaining overweight and obesity in children and adolescents of Asian Indian origin: The Calcutta childhood obesity study. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58:125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Nawab T, Khan Z, Khan IM, Ansari MA. Influence of behavioral determinants on the prevalence of overweight and obesity among school going adolescents of Aligarh. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2014;58:121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Flodmark CE, Lissau I, Moreno LA, Pietrobelli A, Widhalm K. New insights into the field of children and adolescents’ obesity: The European perspective. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1189–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Lazarus R, Baur L, Webb K, Blyth F. Body mass index in screening for adiposity in children and adolescents: Systematic evaluation using receiver operating characteristic curves. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:500–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;2:159–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Anderson PM, Butcher KE. Childhood obesity: Trends and potential causes. Future Child. 2006;16:19–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Contributing factors. 2010. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov//obesity/childhood/contributing_factors. html .

html .

20. Patrick H, Nicklas T. A review of family and social determinants of children's eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviours among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Story M, Neumark-stainzer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviours. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:S40–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Chapman G, Maclean H. “Junk food” and “healthy food”: Meanings of food in adolescent women's culture. J Nutr Educ Behav. 1993;25:108–13. [Google Scholar]

24. Dublin: Department of Health and Children; 2005. Department of Health and Children. Obesity: The policy challenges: The report of the national taskforce on obesity. [Google Scholar]

25. Niehoff V. Childhood obesity: A call to action. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient. Care. 2009;4:17–23. [Google Scholar]

26. Ebbelling CB, Sinclair KB, Pereira MA, Garcia-Lago E, Feldman HA, Ludwig DS. Compensation for energy intake from fast food among overweight and lean adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2828–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ebbelling CB, Sinclair KB, Pereira MA, Garcia-Lago E, Feldman HA, Ludwig DS. Compensation for energy intake from fast food among overweight and lean adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2828–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Kapil U, Bhadoria AS. Television viewing and overweight and obesity amongst children. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 11];Biomed J. 2014 37:337–8. Available from: http://biomedj.org/preprintarticle.asp?id = 125654 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Budd GM, Hayman LL. Addressing the childhood obesity crisis. Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2008;33:113–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Moens E, Braet C, Bosmans G, Rosseel Y. Unfavourable family characteristics and their associations with childhood obesity: A cross-sectional study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17:315–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Rawana JS, Morgan AS, Nguyen H, Craig SG. The relation between eating- and weight-related disturbances and depression in adolescence: A review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13:213–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Goldfield GS, Moore C, Henderson K, Buchholz A, Obeid N, Flament MF. Body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, depression, and weight status in adolescents. J Sch Health. 2010;80:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Britz B, Siegfried W, Ziegler A, Lamertz C, Herpertz-Dahlmann BM, Remschmidt H, et al. Rates of psychiatric disorders in a clinical study group of adolescents with extreme obesity and in obese adolescents ascertained via a population based study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1707–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:53–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Zametkin AZ, Zoon CK, Klein HW, Munson S. Psychiatric aspects of child and adolescent obesity: A review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:134–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;43:134–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Overeating among adolescents: Prevalence and associations with weight-related characteristics and psychological health. Pediatrics. 2003;111:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Jansen W, van de Looij-Jansen PM, de Wilde EJ, Brug J. Feeling fat rather than being fat may be associated with psychological well-being in young Dutch adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:128–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Renman C, Engstr I, Silfverdal SA, Aman J. Mental health and psychosocial characteristics in adolescent obesity: A population-based case-control study. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:998–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. JAMA. 2003;289:1813–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. O’Dea JA. School-based health education strategies for the improvement of body image and prevention of eating problems: An overview of safe and successful interventions. Health Educ. 2005;105:11–33. [Google Scholar]

Health Educ. 2005;105:11–33. [Google Scholar]

40. Austin SB, Haines J, Veugelers PJ. Body satisfaction and body weight: Gender differences and sociodemographic determinants. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Kostanski M, Fisher A, Gullone E. Current conceptualisation of body image dissatisfaction: Have we got it wrong? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1317–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Lundstedt G, Edlund B, Engström I, Thurfjell B, Marcus C. Eating disorder traits in obese children and adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Decaluwxe V, Braet C. Prevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:404–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Decaluwxe V, Breat C, Fairburn CG. Binge eating in obese children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Cornette R. The emotional impact of obesity on children. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5:136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cornette R. The emotional impact of obesity on children. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5:136–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. American Academy of Pediatrics. About childhood obesity. [Last accessed 2014 Jul 14]. Available from: http://www.aap.org/obesity/about.html .

How Childhood Obesity Impacts Bone and Muscle Health - OrthoInfo

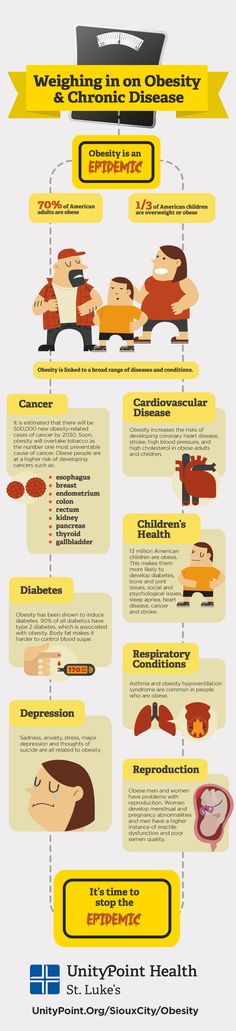

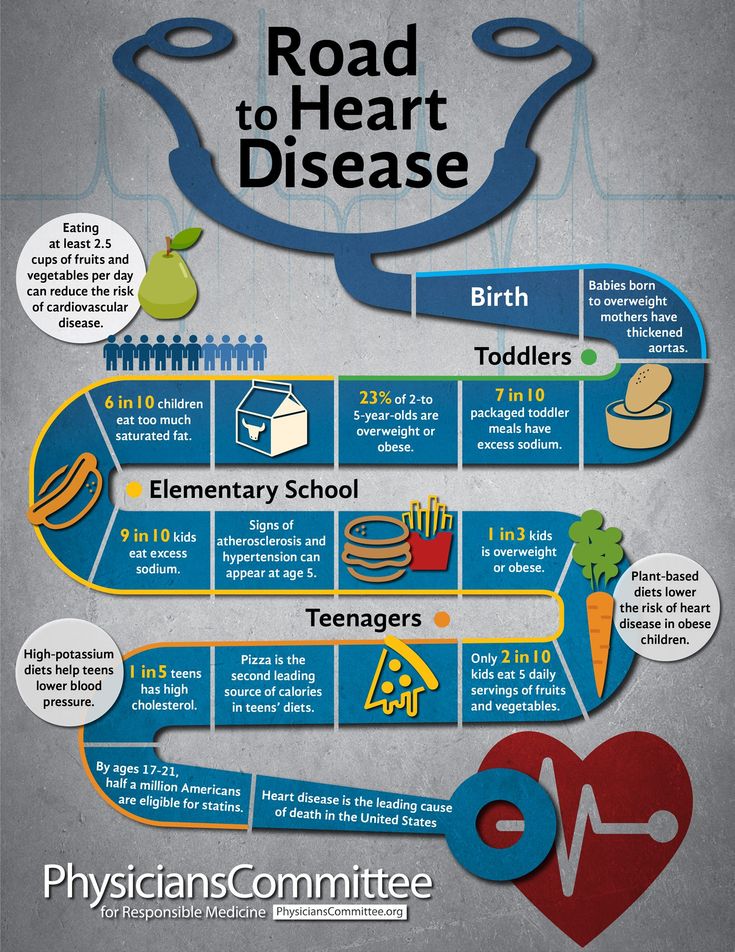

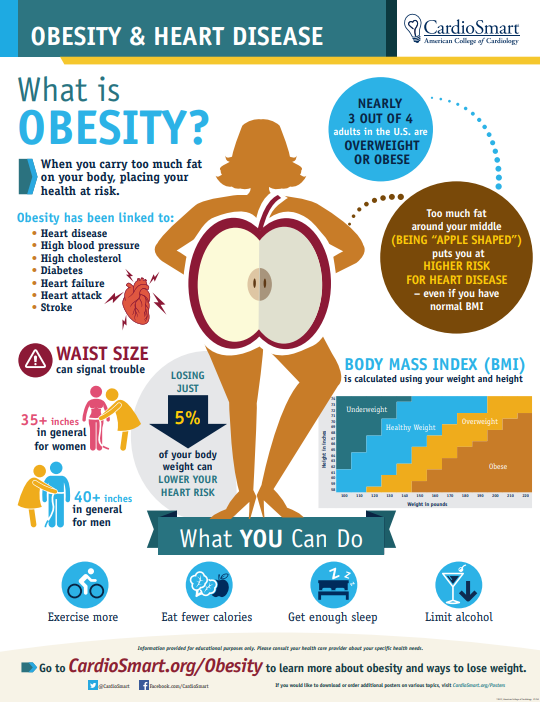

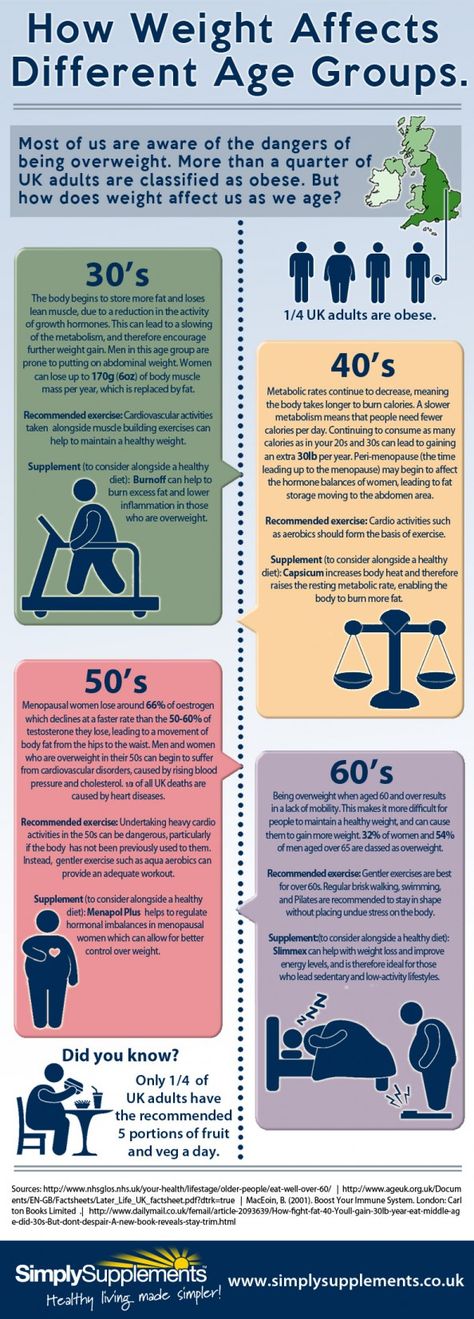

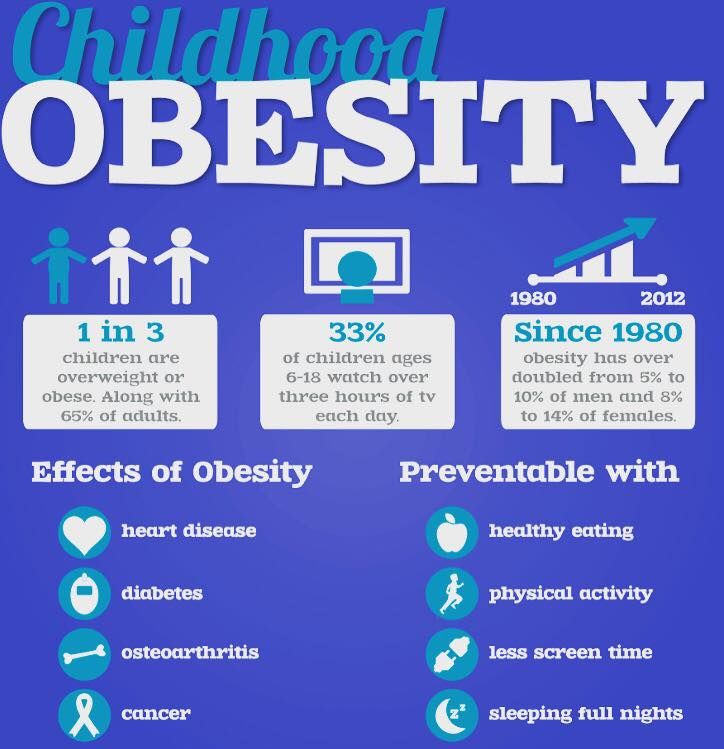

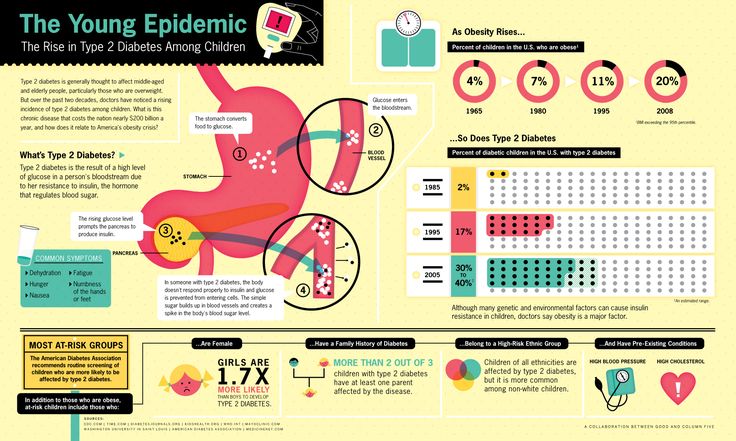

Over the past 20 years, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of children, adolescents and adults diagnosed as overweight or obese in the United States.

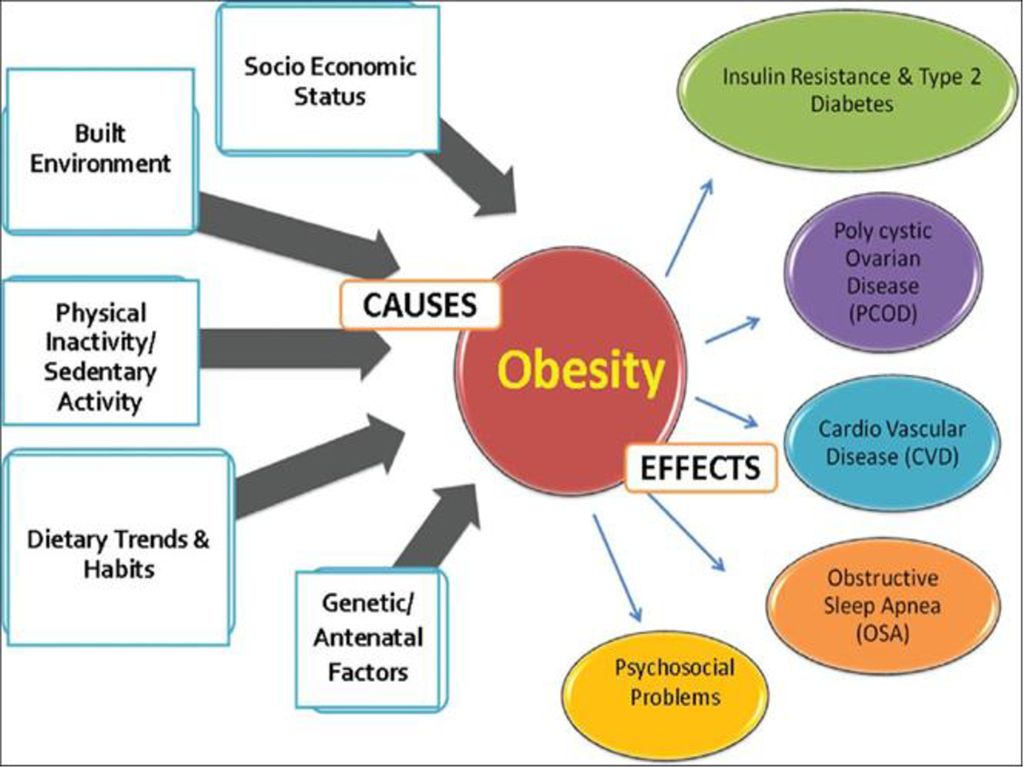

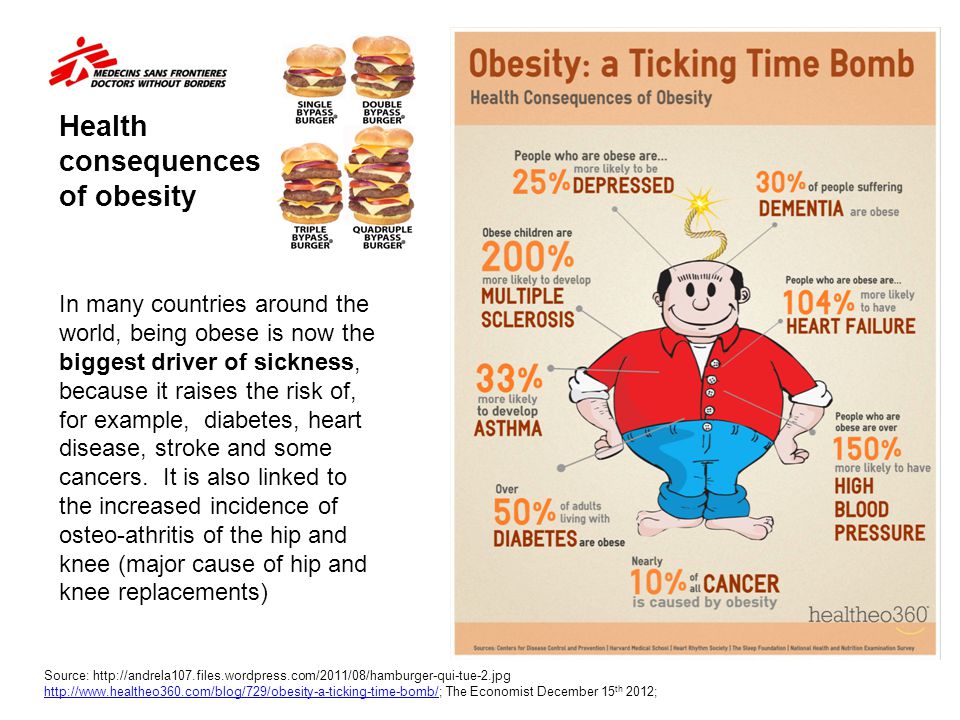

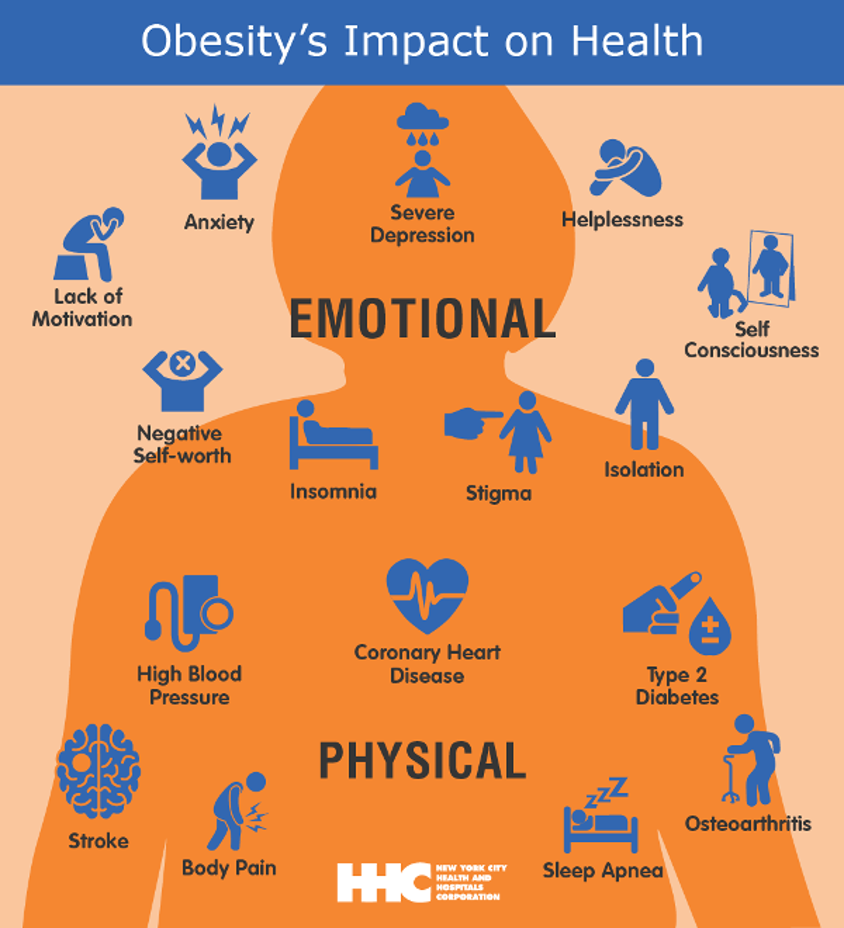

Obesity can cause many health and social problems beginning in childhood, and continuing and intensifying throughout life. These problems include type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, metabolic syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, low self-esteem, and depression.

In addition, excess weight can cause vitamin deficiencies, hormonal imbalances, and increased stress and tension that can affect bone growth and overall musculoskeletal health, causing deformity, pain, and, potentially, a lifetime of limited mobility and diminished life quality.

A healthy diet, along with regular physical activity in childhood — at least 35 to 60 minutes a day — can help ensure a healthy weight and strong bones for life.

Eating well and getting enough physical activity during childhood are habits that lay the foundation for good bone health throughout life.

FatCamera/Getty Images

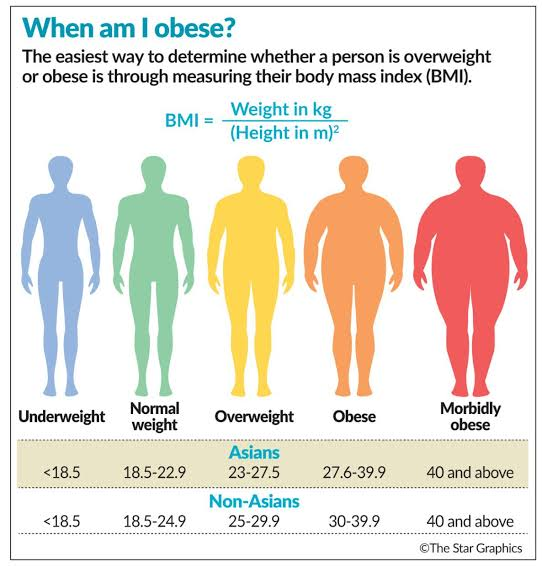

Overweight and obesity are labels for weight ranges that exceed what is generally considered healthy for a given height, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

These weight ranges are identified through a child or adult's body mass index (BMI), which is calculated annually based on a child's weight, height, age, and sex, typically beginning at age 2.

- Children and adolescents with a BMI between, at, or above the 85th percentile, and lower than the 95th percentile, are considered overweight.

- Children and adolescents with a BMI greater than the 95th percentile are considered obese.

Childhood obesity is among the most serious health challenges of the 21st century.

- Over the past three decades, the prevalence of children in the U.S. who are obese has doubled, while the number of adolescents who are obese has tripled.

- About one in eight preschoolers (ages 2 to 5) in the U.S. are obese.

- Children who are overweight or obese as preschoolers are five times as likely as normal-weight children to be overweight or obese as adults.

Generally, obesity is thought to be the result of eating too many calories and not getting enough physical activity (too much energy in and too little energy out). However, the actual causes of obesity often are more complex. In fact, a combination of genetics, activity level, diet, and the environment in which a child lives and plays can contribute to weight. For example, if a child has one obese biological parent, the odds are roughly 3:1 that the child will have a BMI in the obese range.

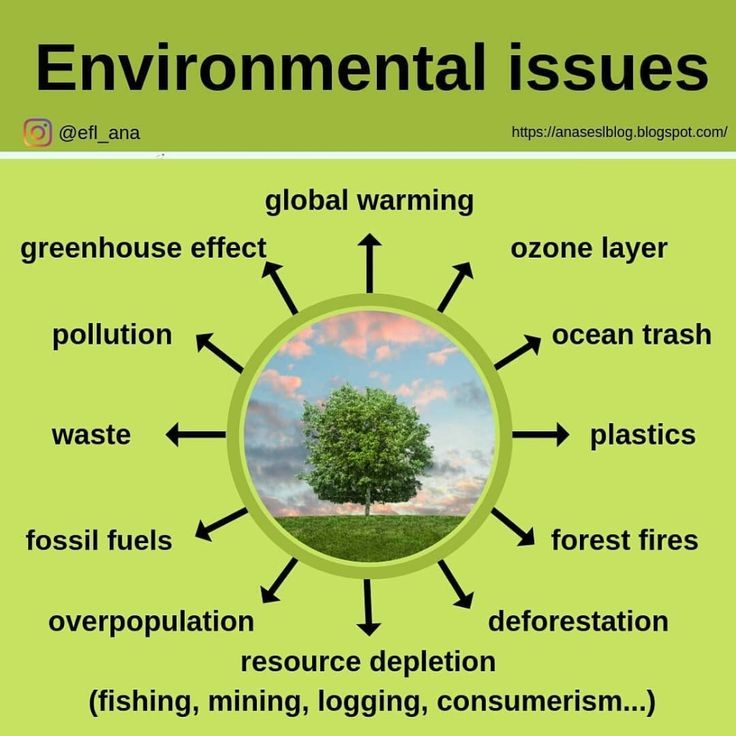

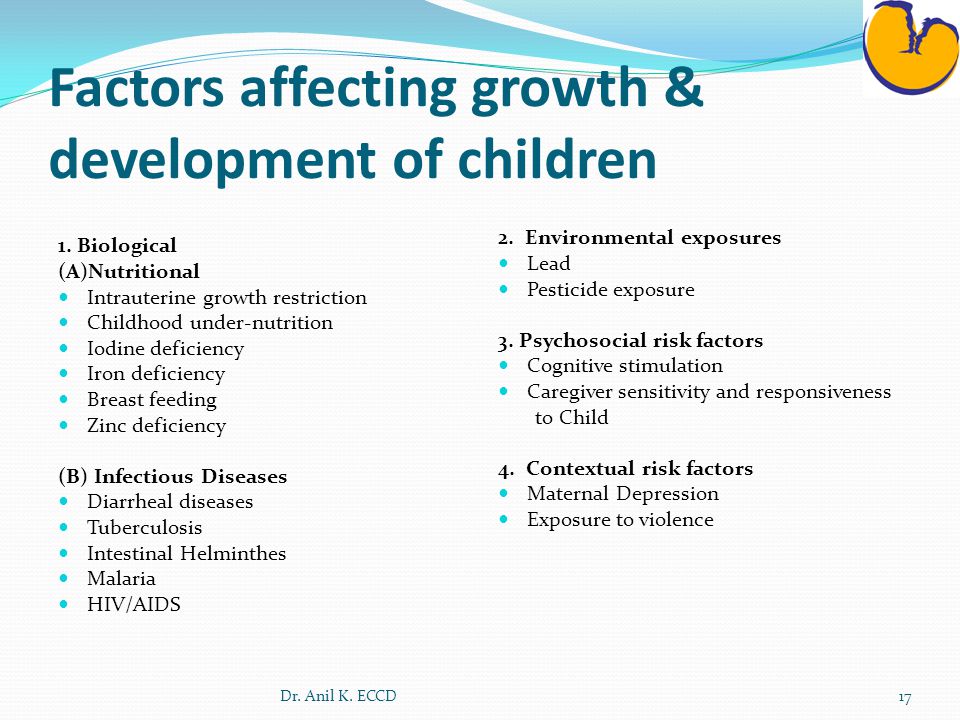

According to the CDC, the environmental factors that may contribute to excess weight in children and adolescents include:

- Greater availability of less healthy foods and sugary drinks.

- Advertising of less healthy foods.

- Lack of daily, quality physical activity in schools.

- No safe and appealing place to play or be active. This is a problem in many communities.

- Limited access to healthy, affordable foods.

- Increasing portion sizes.

- Lack of breastfeeding support.

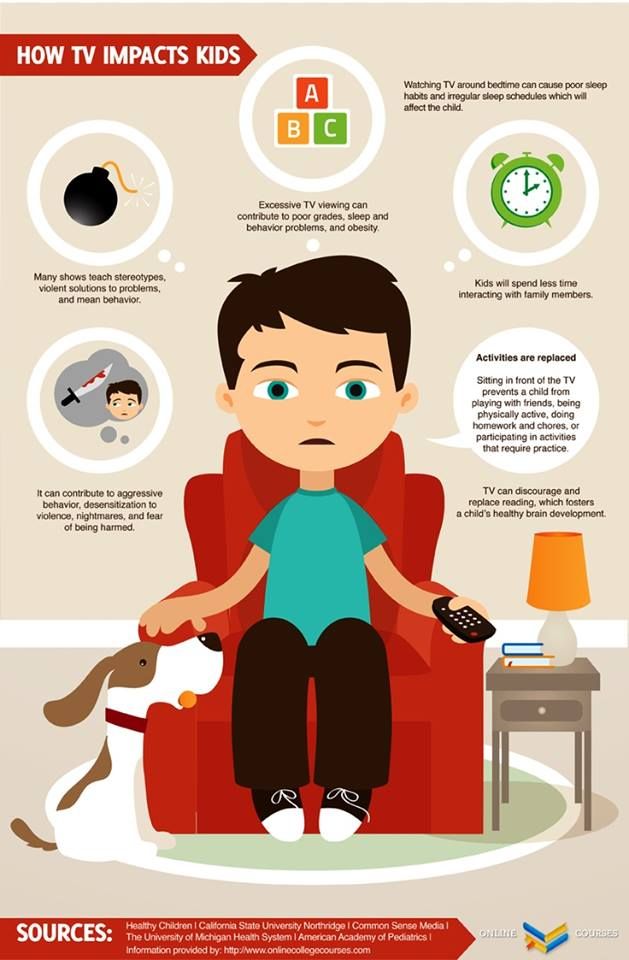

- Greater exposure to television and media. U.S. children ages 8 to 18 spend an average of 7.5 hours a day using entertainment media, including TV, computers, video games, cell phones, and movies.

For some children, an increase in weight may be caused by a condition or disease.

Diseases and conditions that may cause, or contribute to, weight gain include hypothyroidism, Cushing's syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, and Kleinefelter's syndrome.

Leading a sedentary lifestyle may contribute to excess weight in children and adolescents.

Thinkstock

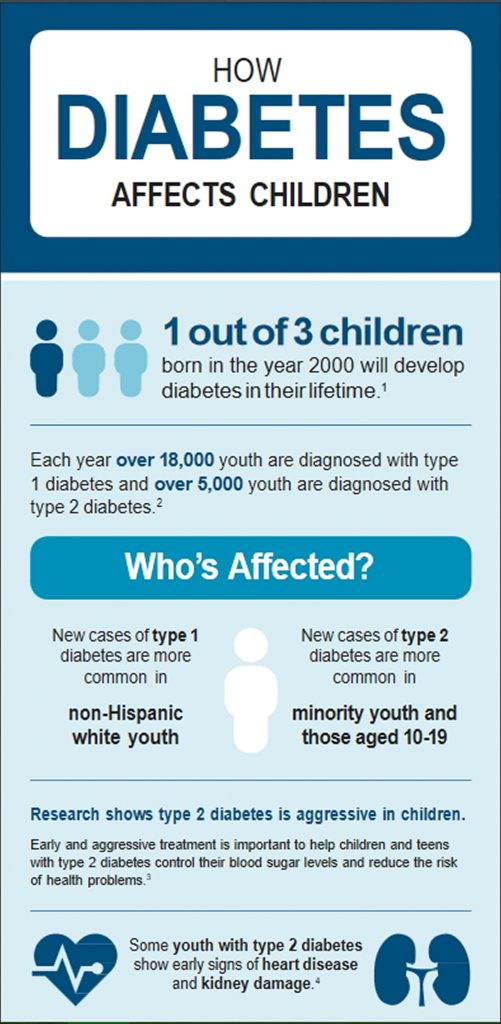

Childhood obesity can have a harmful effect on the body in a variety of ways. According to the CDC, children diagnosed as obese or overweight are more likely to have:

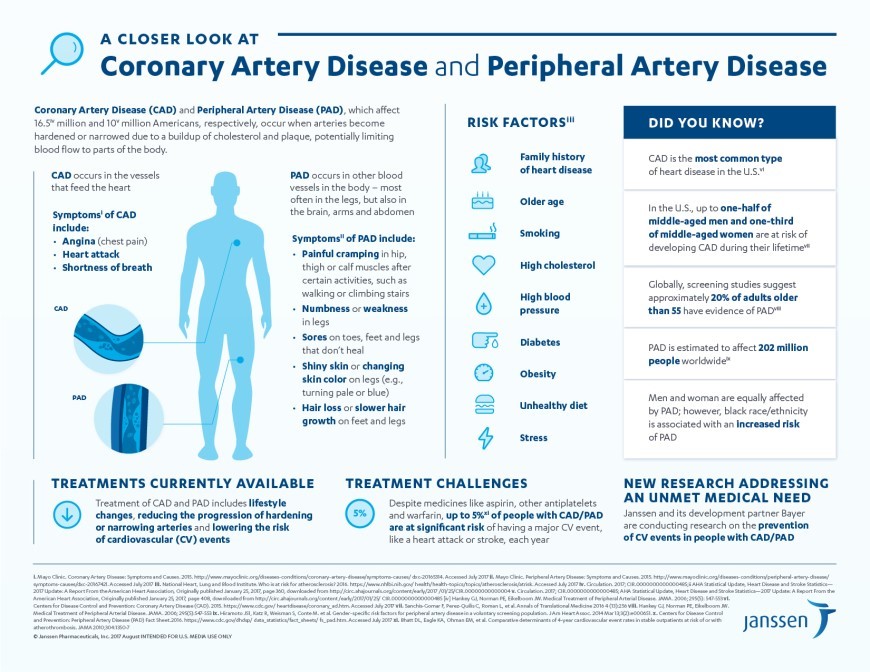

- High blood pressure and high cholesterol, both of which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

- Increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes.

- Breathing problems such as sleep apnea and asthma.

- Liver disease, gallstones, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- A greater risk of social and psychological problems.

Too much weight also can seriously impact the growth and health of bones, joints, and muscles.

Bones grow in size and strength during childhood. Excess weight can damage the growth plate — the area of developing cartilage tissue at the end of the body's arm, leg, and other long bones. Growth plates regulate and help determine the length and shape of a bone at full growth or maturity.

Growth plates regulate and help determine the length and shape of a bone at full growth or maturity.

Too much weight places excess stress on the growth plate, which can lead to early arthritis, a greater risk for broken bones, and other serious conditions, such as slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) and Blount's disease.

Slipped Capital Femoral EpiphysisSlipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is an orthopaedic disorder of the adolescent hip. It occurs when the ball at the head (upper end) of the femur (thighbone) slips off in a backward direction due to weakness of the growth plate. The condition can cause weeks or months of hip or knee pain, and an intermittent limp. In severe cases, the adolescent may be unable to bear any weight on the affected leg.

In this illustration of SCFE, the femoral head has shifted slightly downward off the neck of the bone through the growth plate (arrow).

Courtesy of John Killian, MD, Birmingham, AL

The condition is not rare, and often develops during periods of accelerated growth or shortly after the onset of puberty. Hormonal dysfunction associated with obesity may alter growth plate function in a way that can predispose a child's hip to slip. In addition, the extra weight also may increase the sheer forces across the proximal femoral growth plate contributing to the slip.

Hormonal dysfunction associated with obesity may alter growth plate function in a way that can predispose a child's hip to slip. In addition, the extra weight also may increase the sheer forces across the proximal femoral growth plate contributing to the slip.

Treatment of SCFE usually begins within 24 to 48 hours of diagnosis and consists of stabilizing the slipped growth plate with a screw to prevent further slippage.

In children diagnosed with obesity, it can be more challenging to appropriately position and secure the ball of the femur bone without complications.

Blount's DiseaseBlount's disease, or severe bowing of the legs, is another condition in which hormonal changes and increased stress on a growth plate, caused by excess weight, can lead to irregular growth and deformity. Progressive deformity, rather than knee discomfort, is the most common complaint.

An adolescent with Blount's disease.

Courtesy of Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children

In younger children and less severe cases, a leg brace or orthotic may correct the problem. However, some children may need surgery. Surgery consists of either:

However, some children may need surgery. Surgery consists of either:

- Growth modulation. During ths procedure, the surgeon inserts a metal plate and screws around the growth plate, which gradually corrects the bowing over time.

- Tibial osteotomy, in which the surgeon removes a wedge of bone from the outside of the tibia (shinbone) under the healthy side of the knee. When the surgeon closes the wedge, it straightens the leg.

Children diagnosed as overweight or obese have a higher risk of complications related to these procedures, including infection, delayed bone healing, failure of fixation, and recurrence of Blount's disease.

Fractures and Related ComplicationsChildren diagnosed as obese or overweight may have a higher risk for fractures (broken bones) due to stress on the bones or because of weakened bones secondary to inactivity. In addition, these children may have more complications that can delay or alter treatment outcomes.

For example, traditional metal implants may not be sufficiently strong to repair broken or misaligned bones. In addition, crutches may be difficult to use for children who are obese or overweight, and cast immobilization may not sufficiently stabilize broken bones. As a result, surgery is often required in addition to casting.

Flat FeetChildren who are overweight or obese often have painful, flat feet that tire easily and prevent them from walking long distances. Many children with flat feet are treated with orthotics and stretching exercises focused on the Achilles tendon (heel cord).

Because weight loss is often enough to ease the pain of flat feet, low impact weight reduction exercises, such as swimming, may be recommended.

Impaired MobilityChildren diagnosed with obesity often have difficulties with their coordination, called developmental coordination disorder (DCD). The symptoms of DCD may include:

- Clumsiness

- Problems with gross motor coordination such as jumping, hopping, or standing on one foot

- Problems with visual or fine motor coordination, such as writing, using scissors, tying shoelaces, or tapping one finger to another

Developmental coordination disorder may impair or limit a child's ability to exercise, potentially resulting in more weight gain. Physical and occupational therapy may improve DCD.

Physical and occupational therapy may improve DCD.

Children who are obese have a higher rate of anesthetic complications than normal-weight children. In addition, children diagnosed as overweight or obese are more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, and other endocrine abnormalities that may affect surgical and other treatment, and ultimately, delay or impair bone healing and a return to normal function.

In a very small number of children with extremely high BMIs — 40 or above — bariatric surgery may be recommended to reduce weight and avoid long-term musculoskeletal and other related conditions and complications.

In most children, a diet rich in calcium and other nutrients, along with regular, physical activity — at least 35 to 60 minutes a day — can help to minimize weight gain, while helping to build and maintain strong bones.

To Top

Reviewed by members of

POSNA (Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America)

The Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) is a group of board eligible/board certified orthopaedic surgeons who have specialized training in the care of children's musculoskeletal health.

Learn more about this topic at POSNA's OrthoKids website:

Obesity in Children

Obesity in infancy impairs cognitive ability in childhood

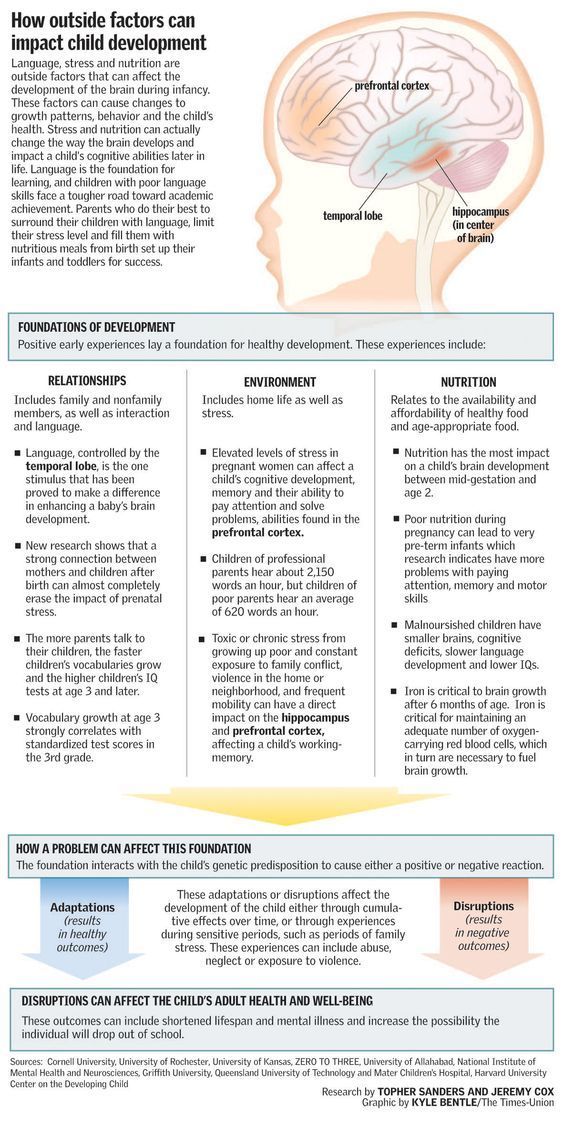

Being overweight in a young child has a negative impact on later development, according to an article published in the journal Obesity . American scientists, measuring the weight of children under the age of two years and their cognitive abilities at five and eight years old, found that obesity in infancy impairs working memory and spatial thinking at a later age.

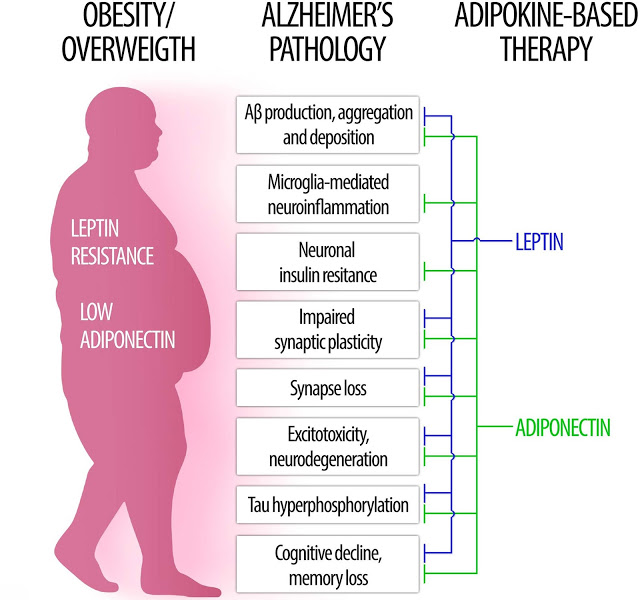

A lot is already known about the relationship between weight and cognitive functions. Obesity, for example, can lead to memory impairment, and experiments on rats show that overweight animals are associated with a reduced number of synapses in the prefrontal and periural cortex, which leads to a deterioration in their cognitive functions.

So far, however, it is not clear how obesity affects the process of early childhood brain development and the formation of the first cognitive functions. Scientists from Brown University led by Joseph Braun decided to study this. Their study involved 223 children whose weight and height (to calculate body mass index) were measured in infancy - up to the age of two years.

Scientists from Brown University led by Joseph Braun decided to study this. Their study involved 223 children whose weight and height (to calculate body mass index) were measured in infancy - up to the age of two years.

Then, at the age of five and eight, the children underwent a series of standardized cognitive tests: speech, reaction time to the appearance of a visual stimulus, processing of auditory stimuli, working memory functioning. In addition, the children had to go through an adapted computerized version of the Morris water maze, in which the classic version requires a laboratory mouse to find a platform in a tub of water, guided by external signs. Such an experiment is aimed at evaluating both the decision-making process and the work of spatial memory.

After analyzing the data and taking into account information about the mother's life during childbirth (diet, smoking and alcohol consumption) as well as her age and race as side variables, the researchers found that when the baby's weight in infancy increased by one standard deviation, its overall level later on, intelligence was 1. 4 standard deviations less, spatial perception 1.7, and working memory 2.4 standard deviations less than those who were slender in infancy. All other relationships were statistically insignificant.

4 standard deviations less, spatial perception 1.7, and working memory 2.4 standard deviations less than those who were slender in infancy. All other relationships were statistically insignificant.

A healthy lifestyle is very important during a child's early development, and this study shows the importance of maintaining a healthy weight for a child's cognitive development. It should be noted that the sample in the study was small: that is why the relationship could be traced only between obesity and part of the cognitive indicators. In the future, scientists say, it is necessary to conduct further research.

The study of the negative impact of childhood obesity on both their health and intellectual development is very important, since the number of overweight children is growing every year: last fall, scientists, for example, found that over the past 40 years, the number of overweight children weight increased by 10 times.

Elizaveta Ivtushok

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Childhood obesity

Childhood obesity is a problem that affects hundreds of children and adolescents every year. Extra pounds often become for children the beginning of the path to health problems that were previously considered problems of adults. Childhood obesity leads to low self-esteem and other psychological problems.

One of the best strategies for dealing with this problem is to improve your eating habits and select specific exercises for your entire family.

Childhood obesity problems

Childhood obesity has reached epidemic levels in both developed and developing countries. Being overweight in childhood has a significant impact on both physical and psychological health. Overweight and obese children often remain with this problem into adulthood.

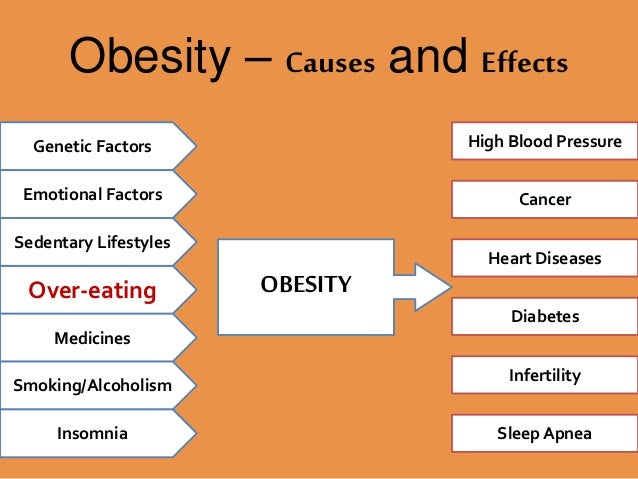

The mechanism of development of obesity is not fully understood, since this disease has many causes. Environmental factors, lifestyle preferences and cultural environment play a key role in the increase in the prevalence of obesity worldwide. Overweight and obesity are often the result of increased calorie and fat intake. But there is also supporting evidence that excessive consumption of sugar in soft drinks, increased portion sizes, and persistent reductions in physical activity play an important role in rising rates of obesity worldwide.

Overweight and obesity are often the result of increased calorie and fat intake. But there is also supporting evidence that excessive consumption of sugar in soft drinks, increased portion sizes, and persistent reductions in physical activity play an important role in rising rates of obesity worldwide.

Childhood obesity can seriously affect a child's physical health, social and emotional well-being and self-esteem. It is also associated with poor academic performance and a lower quality of life for children. Many comorbidities such as metabolic, cardiovascular, orthopedic, neurological, hepatic, pulmonary and renal disorders are also observed in association with obesity.

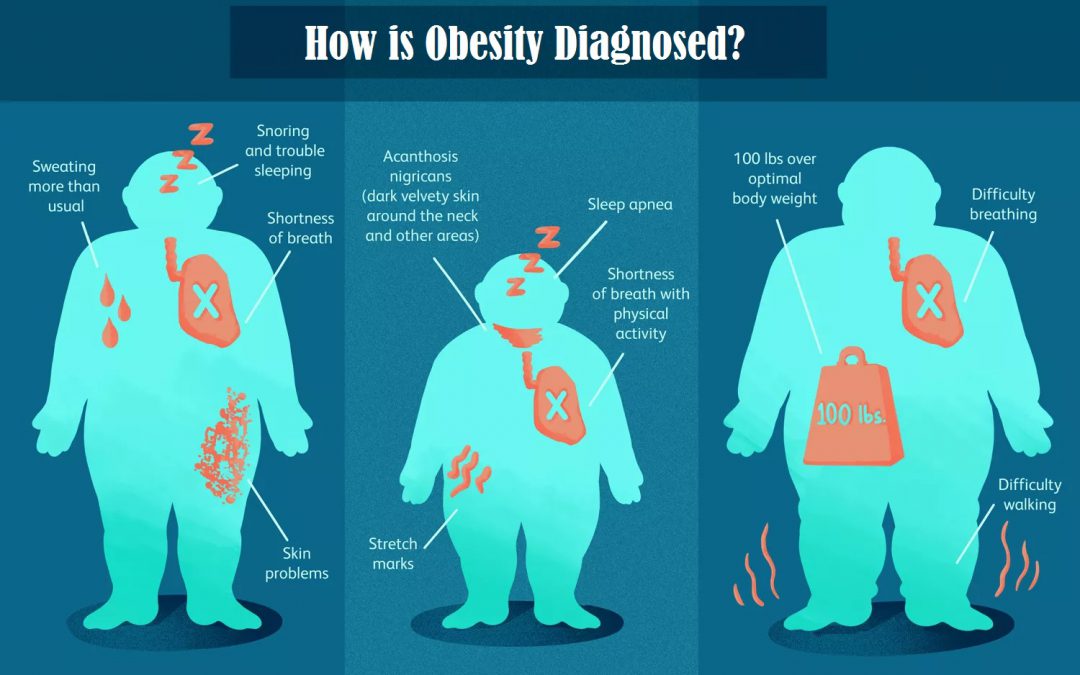

Symptoms

Extra pounds are not always overweight. Some children have a larger than average physique. And at different stages of development, children usually have different amounts of body fat. It can be difficult to tell if your child's weight is a health problem by looking at it.

BMI (BMI, Body Mass Index), which is a weight-for-height benchmark, is a common measure of overweight and obesity. A pediatrician can use growth charts and other tests to find out if a small patient's weight is within acceptable limits.

A pediatrician can use growth charts and other tests to find out if a small patient's weight is within acceptable limits.

When to Seek Advice

If you are worried that your child is gaining too much weight, talk to your pediatrician. The doctor will review the child's growth and development history, the weight-to-height ratio, taking into account the family tree, and also examine the child's place in the growth chart. This will help determine if your child's weight is in an unhealthy range.

Causes

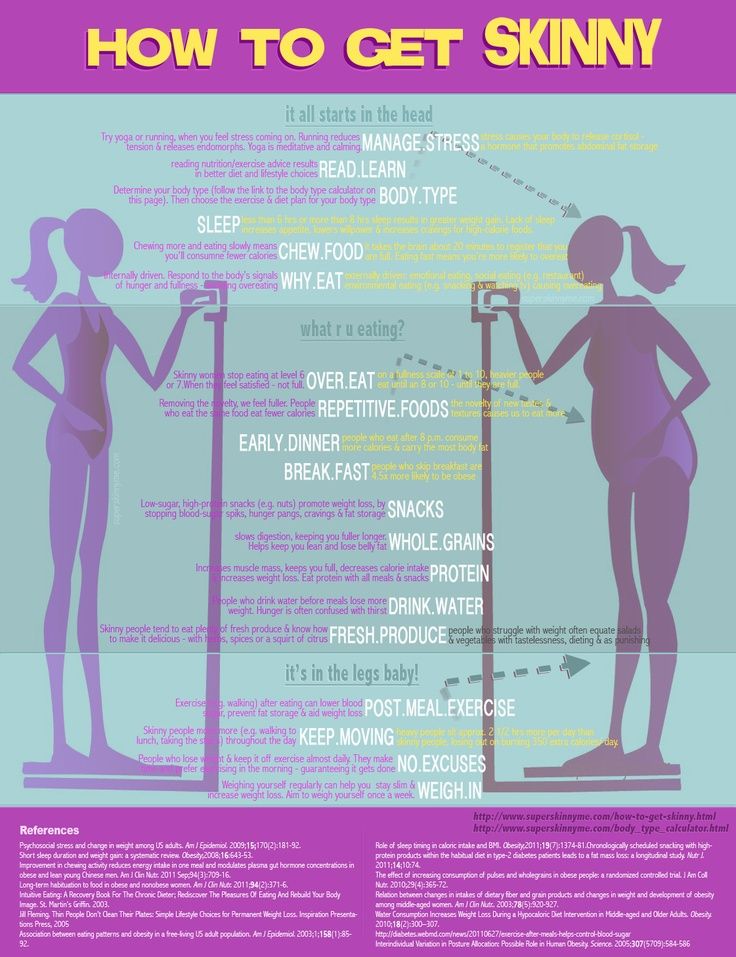

Lifestyle problems (low activity, high calories from food and drink) are the main causes of childhood obesity. But hormonal factors and genetics also play a role.

Family history, psychological factors and lifestyle all contribute to the development of obesity in children. Teenagers and children whose parents or other family members are overweight are more likely to inherit the same body structure. But the main reason is a combination of eating too often and not being active enough.

Physical inactivity is a major cause of childhood obesity. People of all ages tend to gain weight if they are less active. Exercise burns calories and helps maintain a healthy weight. Children who are not encouraged to be active may be less likely to burn extra calories by playing sports, playing on the playground, or engaging in other forms of physical activity.

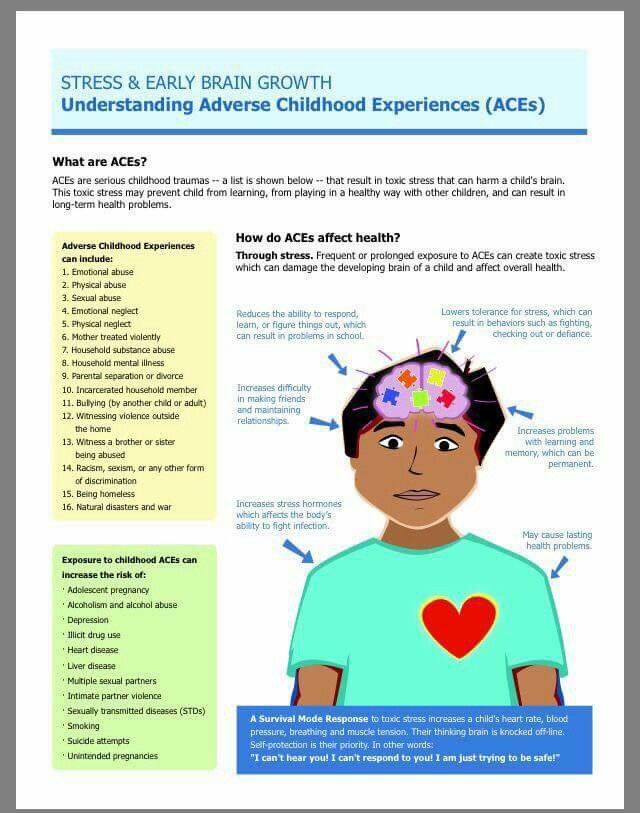

Psychological problems are another factor leading to obesity. Boys and children who are bored, stressed or depressed may eat more to cope with negative emotions.

List of risk factors

Many factors, often in combination, increase the risk of this problem:

- Diet. Frequent consumption of high-calorie foods (fast food, pastries) leads to weight gain in the child. Desserts and sweets can cause weight gain, and high-sugar drinks, including fruit juices, have been linked to obesity in some people.

- No physical activity. Children who move little and do not play sports are more likely to gain weight (they do not burn the required number of calories in a day).

Too much time spent inactive (watching TV, playing video games) also contributes to this problem.

Too much time spent inactive (watching TV, playing video games) also contributes to this problem. - Family factors. If your child is born into a family of overweight people, then he may be prone to weight gain. This is especially true in an environment where high-calorie foods are always available and sports activities are discouraged.

- Psychological factors. Personal, parental and family stress increase the risk of obesity in a child. Some children overeat to cope with problems and thus overcome stress. Their parents may have similar tendencies.

- Socio-economic parameters. Residents of individual communities have limited resources and limited access to supermarkets. As a result, they can buy fast foods that do not spoil so quickly (mivina, frozen meals, crackers, cookies). Moreover, people living in low-income areas may not have access to a safe place to exercise.

- Some medicines. Prescription drugs can increase your risk of developing this disease.

These include prednisone, amitriptyline, lithium, paroxetine (Paxil), gabapentin, and propranolol (Inderal, Hemangeol).

These include prednisone, amitriptyline, lithium, paroxetine (Paxil), gabapentin, and propranolol (Inderal, Hemangeol).

Physical, social, emotional complications

Childhood obesity often causes complications in the child's physical, social and emotional well-being.

Physical complications of childhood obesity may include:

- Diabetes. This chronic condition affects how your child's body uses sugar (glucose). Obesity and a sedentary lifestyle increase the risk of developing this condition.

- High cholesterol, blood pressure. Poor nutrition can cause your child to develop one or both of these conditions. These factors can contribute to the buildup of plaque in the arteries, which often leads to narrowing and hardening of the arteries.

- Joint pain. Being overweight puts extra stress on your hips and knees. Childhood obesity can cause pain and sometimes injury in the hips, knees, and back.

- Breathing problems.

Asthmatic diseases occur in overweight patients. Obese children are also more likely to develop obstructive sleep apnea, a serious disorder in which breathing constantly stops and speeds up during sleep.

Asthmatic diseases occur in overweight patients. Obese children are also more likely to develop obstructive sleep apnea, a serious disorder in which breathing constantly stops and speeds up during sleep. - Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). This is a disease that usually does not cause any symptoms, but leads to the accumulation of fatty deposits in the liver. NAFLD can lead to scarring and damage to the liver.

Obese children may be teased or bullied by their peers. This can lead to lower self-esteem and an increased risk of depression and anxiety.

Prevention

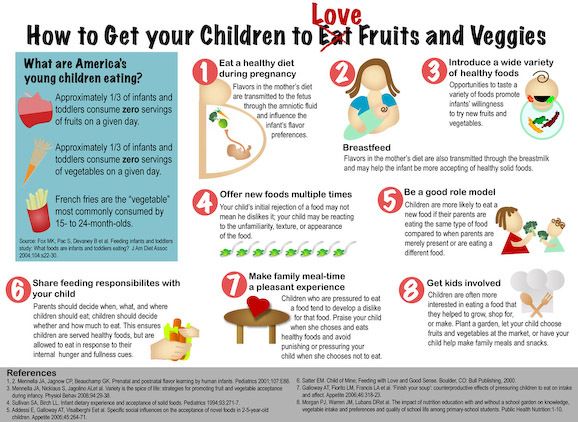

You can help prevent teens and preschoolers from gaining weight by doing the following:

- Set a good example. Make healthy eating and regular activity a family affair.

- Provide healthy snacks. Options include butter-free popcorn, fruit with low-fat yogurt, carrots with hummus, or whole grain cereal with low-fat milk.

- Choose non-food rewards.