How does corporal punishment affect a child

Corporal punishment and health

Corporal punishment and health- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Fact sheets/

- Detail/

- Corporal punishment and health

Key facts

- Corporal or physical punishment is highly prevalent globally, both in homes and schools.

Around 60% of children aged 2–14 years regularly suffer physical punishment by their parents or other caregivers. In some countries, almost all students report being physically punished by school staff. The risk of being physically punished is similar for boys and girls, and for children from wealthy and poor households.

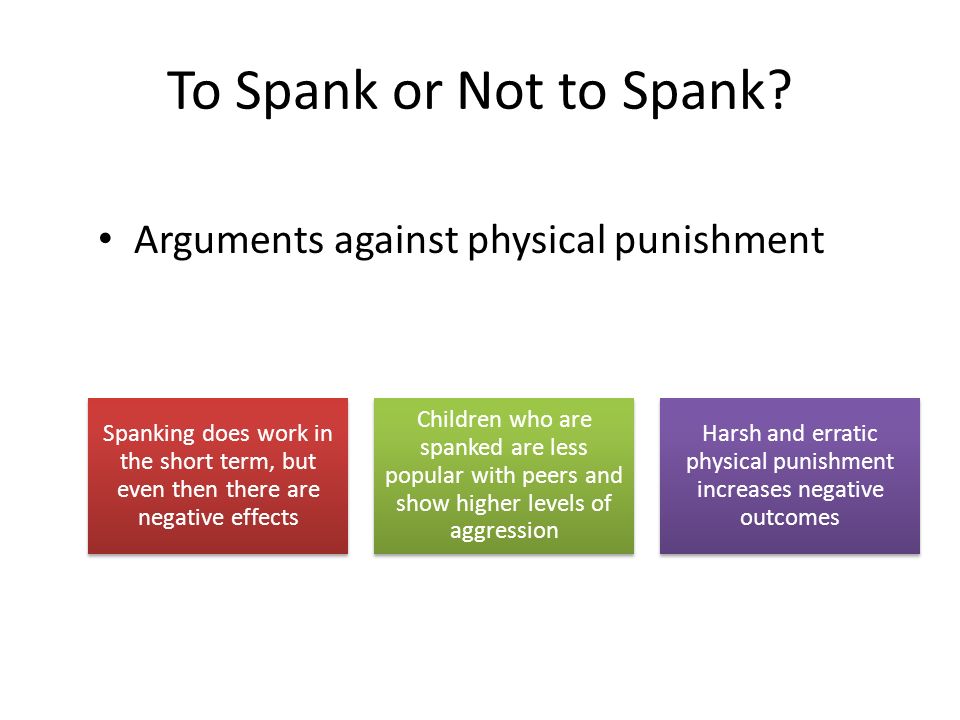

- Evidence shows corporal punishment increases children’s behavioural problems over time and has no positive outcomes.

- All corporal punishment, however mild or light, carries an inbuilt risk of escalation. Studies suggest that parents who used corporal punishment are at heightened risk of perpetrating severe maltreatment.

- Corporal punishment is linked to a range of negative outcomes for children across countries and cultures, including physical and mental ill-health, impaired cognitive and socio-emotional development, poor educational outcomes, increased aggression and perpetration of violence.

- Corporal punishment is a violation of children’s rights to respect for physical integrity and human dignity, health, development, education and freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- The elimination of violence against children is called for in several targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development but most explicitly in Target 16.2: “end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children”.

- Corporal punishment and the associated harms are preventable through multisectoral and multifaceted approaches, including law reform, changing harmful norms around child rearing and punishment, parent and caregiver support, and school-based programming.

Overview

Corporal or physical punishment is defined by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which oversees the Convention on the Rights of the Child, as “any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.”

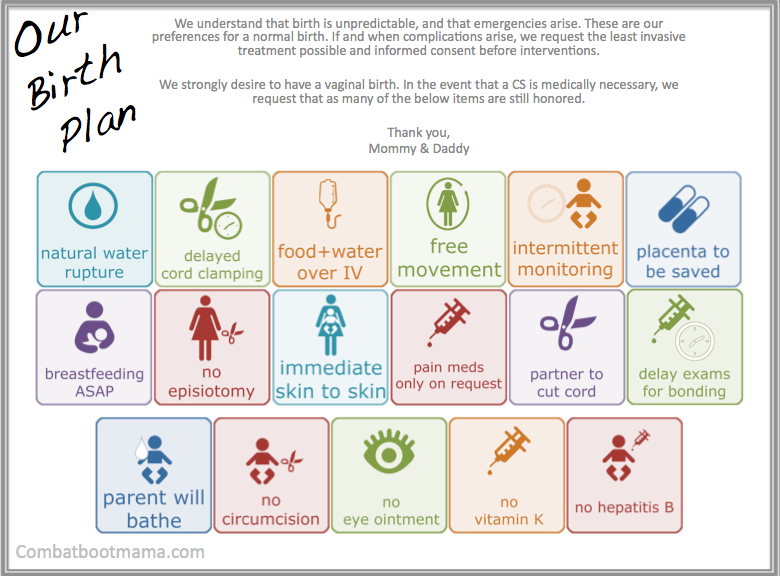

According to the Committee, this mostly involves hitting (smacking, slapping, spanking) children with a hand or implement (whip, stick, belt, shoe, wooden spoon or similar) but it can also involve, for example, kicking, shaking or throwing children, scratching, pinching, biting, pulling hair or boxing ears, forcing children to stay in uncomfortable positions, burning, scalding or forced ingestion.

Other non-physical forms of punishment can be cruel and degrading, and thus also incompatible with the Convention, and often accompany and overlap with physical punishment. These include punishments which belittle, humiliate, denigrate, scapegoat, threaten, scare or ridicule the child.

Scope

UNICEF’s data from nationally representative surveys in 56 countries 2005–2013 show that approximately 6 out of 10 children aged 2–14 years experienced corporal punishment by adults in their households in the past month. On average, 17% of children experienced severe physical punishment (being hit on the head, face or ears or hit hard and repeatedly) but in some countries this figure exceeds 40%. Large variations across countries and regions show the potential for prevention.

Apart from some countries where rates among boys are higher, results from comparable surveys show that the prevalence of corporal punishment is similar for girls and boys. Young children (aged 2–4 years) are as likely, and in some countries more likely, as older children (aged 5–14 years) to be exposed to physical punishment, including harsh forms. Physical disciplinary methods are used even with very young children – comparable surveys conducted in 29 countries 2012–2016 show that 3 in 10 children aged 12–23 months are subjected to spanking.

Physical disciplinary methods are used even with very young children – comparable surveys conducted in 29 countries 2012–2016 show that 3 in 10 children aged 12–23 months are subjected to spanking.

Most children are exposed to both psychological and physical means of punishment. Many parents and caregivers report using non-violent disciplines measures (such as explaining why the child’s behaviour was wrong, taking away privileges) but these are usually used in combination with violent methods. Children who experience only non-violent forms of discipline are in the minority.

One in 2 children aged 6–17 years (732 million) live in countries where corporal punishment at school is not fully prohibited. Studies have shown that lifetime prevalence of school corporal punishment was above 70% in Africa and Central America, past-year prevalence was above 60% in the WHO Regions of Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asia, and past-week prevalence was above 40% in Africa and South-East Asia. Lower rates were found in the WHO Western Pacific Region, with lifetime and past year prevalence around 25%. Physical punishment appeared to be highly prevalent at both primary and secondary school levels.

Lower rates were found in the WHO Western Pacific Region, with lifetime and past year prevalence around 25%. Physical punishment appeared to be highly prevalent at both primary and secondary school levels.

Consequences

Corporal punishment triggers harmful psychological and physiological responses. Children not only experience pain, sadness, fear, anger, shame and guilt, but feeling threatened also leads to physiological stress and the activation of neural pathways that support dealing with danger. Children who have been physically punished tend to exhibit high hormonal reactivity to stress, overloaded biological systems, including the nervous, cardiovascular and nutritional systems, and changes in brain structure and function.

Despite its widespread acceptability, spanking is also linked to atypical brain function like that of more severe abuse, thereby undermining the frequently cited argument that less severe forms of physical punishment are not harmful.

A large body of research shows links between corporal punishment and a wide range of negative outcomes, both immediate and long-term:

- direct physical harm, sometimes resulting in severe damage, long-term disability or death;

- mental ill-health, including behavioural and anxiety disorders, depression, hopelessness, low self-esteem, self-harm and suicide attempts, alcohol and drug dependency, hostility and emotional instability, which continue into adulthood;

- impaired cognitive and socio-emotional development, specifically emotion regulation and conflict solving skills;

- damage to education, including school dropout and lower academic and occupational success;

- poor moral internalization and increased antisocial behaviour;

- increased aggression in children;

- adult perpetration of violent, antisocial and criminal behaviour;

- indirect physical harm due to overloaded biological systems, including developing cancer, alcohol-related problems, migraine, cardiovascular disease, arthritis and obesity that continue into adulthood;

- increased acceptance and use of other forms of violence; and

- damaged family relationships.

There is some evidence of a dose–response relationship, with studies finding that the association with child aggression and lower achievement in mathematics and reading ability became stronger as the frequency of corporal punishment increased.

Risk factors

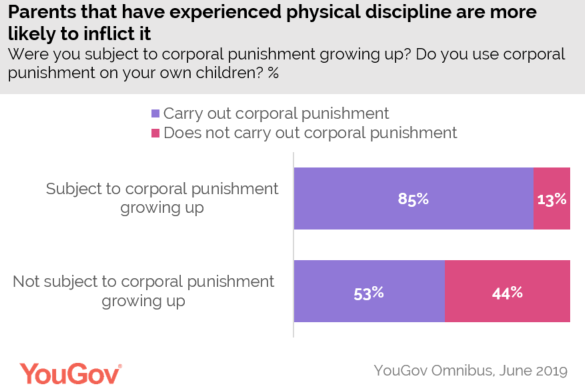

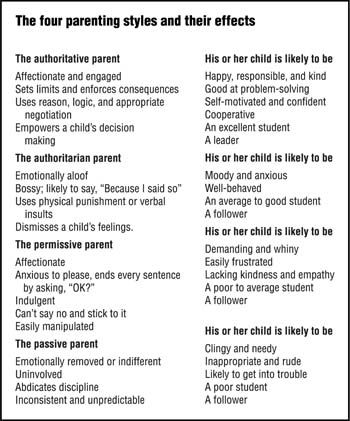

There are few differences in prevalence of corporal punishment by sex or age, although in some places boys and younger children are more at risk. Children with disabilities are more likely to be physically punished than those without disabilities. Parents who were physically punished as children are more likely to physically punish their own children.

In most of the countries with data, children from wealthier households are equally likely to experience violent discipline as those from poorer households. In contrast, in some resource-poor settings, especially where education systems have undergone rapid expansion, the strain on teachers resulting from the limited human and physical resources may lead to a greater use of corporal punishment in the classroom.

Prevention and response

The INSPIRE technical package presents several effective and promising interventions, including:

- Implementation and enforcement of laws to prohibit physical punishment. Such laws ensure children are equally protected under the law on assault as adults and serve an educational rather than punitive function, aiming to increase awareness, shift attitudes towards non-violent childrearing and clarify the responsibilities of parents in their caregiving role.

- Norms and values programmes to transform harmful social norms around child-rearing and child discipline.

- Parent and caregiver support through information and skill-building sessions to develop nurturing, non-violent parenting.

- Education and life skills interventions to build a positive school climate and violence-free environment, and strengthening relationships between students, teachers and administrators.

- Response and support services for early recognition and care of child victims and families to help reduce reoccurrence of violent discipline and lessen its consequences.

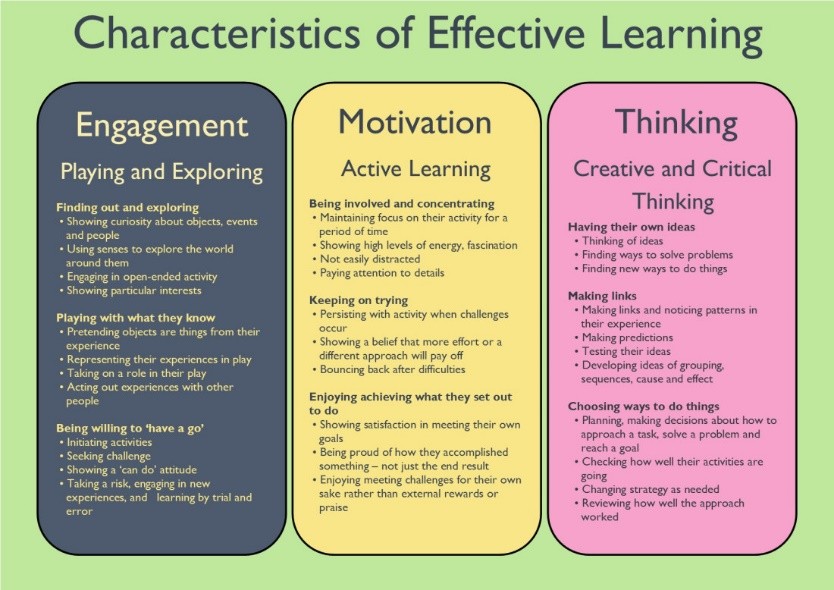

The earlier such interventions occur in children's lives, the greater the benefits to the child (e.g., cognitive development, behavioural and social competence, educational attainment) and to society (e.g., reduced delinquency and crime).

WHO Response

WHO addresses corporal punishment in multiple cross-cutting ways. In collaboration with partners, WHO provides guidance and technical support for evidence-based prevention and response. Work on several strategies from the INSPIRE technical package, including those on legislation, norms and values, parenting, and school-based violence prevention, contribute to preventing physical punishment. The Global status report on violence against children 2020 monitors countries’ progress in implementing legislation and programmes that help reduce it. WHO also advocates for increased international support for and investment in these evidence-based prevention and response efforts.

Violence against children

Violence prevention

- Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children

- International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect

- Violence Against Children – UNICEF Data

The case against spanking

A growing body of research has shown that spanking and other forms of physical discipline can pose serious risks to children, but many parents aren’t hearing the message.

“It’s a very controversial area even though the research is extremely telling and very clear and consistent about the negative effects on children,” says Sandra Graham-Bermann, PhD, a psychology professor and principal investigator for the Child Violence and Trauma Laboratory at the University of Michigan. “People get frustrated and hit their kids. Maybe they don’t see there are other options.”

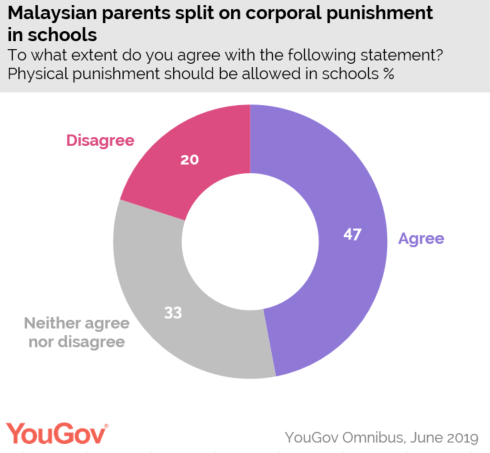

Many studies have shown that physical punishment — including spanking, hitting and other means of causing pain — can lead to increased aggression, antisocial behavior, physical injury and mental health problems for children. Americans’ acceptance of physical punishment has declined since the 1960s, yet surveys show that two-thirds of Americans still approve of parents spanking their kids.

But spanking doesn’t work, says Alan Kazdin, PhD, a Yale University psychology professor and director of the Yale Parenting Center and Child Conduct Clinic. “You cannot punish out these behaviors that you do not want,” says Kazdin, who served as APA president in 2008. “There is no need for corporal punishment based on the research. We are not giving up an effective technique. We are saying this is a horrible thing that does not work.”

“There is no need for corporal punishment based on the research. We are not giving up an effective technique. We are saying this is a horrible thing that does not work.”

Evidence of harm

On the international front, physical discipline is increasingly being viewed as a violation of children’s human rights. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child issued a directive in 2006 calling physical punishment “legalized violence against children” that should be eliminated in all settings through “legislative, administrative, social and educational measures.” The treaty that established the committee has been supported by 192 countries, with only the United States and Somalia failing to ratify it.

Around the world, 30 countries have banned physical punishment of children in all settings, including the home. The legal bans typically have been used as public education tools, rather than attempts to criminalize behavior by parents who spank their children, says Elizabeth Gershoff, PhD, a leading researcher on physical punishment at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Physical punishment doesn’t work to get kids to comply, so parents think they have to keep escalating it. That is why it is so dangerous,” she says.

After reviewing decades of research, Gershoff wrote the Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children, published in 2008 in conjunction with Phoenix Children’s Hospital. The report recommends that parents and caregivers make every effort to avoid physical punishment and calls for the banning of physical discipline in all U.S. schools. The report has been endorsed by dozens of organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Medical Association and Psychologists for Social Responsibility.

After three years of work on the APA Task Force on Physical Punishment of Children, Gershoff and Graham- Bermann wrote a report in 2008 summarizing the task force’s recommendations. That report recommends that “parents and caregivers reduce and potentially eliminate their use of any physical punishment as a disciplinary method. ” The report calls on psychologists and other professionals to “indicate to parents that physical punishment is not an appropriate, or even a consistently effective, method of discipline.”

” The report calls on psychologists and other professionals to “indicate to parents that physical punishment is not an appropriate, or even a consistently effective, method of discipline.”

“We have the opportunity here to take a strong stand in favor of protecting children,” says Graham-Bermann, who chaired the task force.

APA’s Committee on Children, Youth and Families (CYF) and the Board for the Advancement of Psychology in the Public Interest unanimously approved a proposed resolution last year based on the task force recommendations. It states that APA supports “parents’ use of non-physical methods of disciplining children” and opposes “the use of severe or injurious physical punishment of any child.” APA also should support additional research and a public education campaign on “the effectiveness and outcomes associated with corporal punishment and nonphysical methods of discipline,” the proposed resolution states. After obtaining feedback from other APA boards and committees in the spring of 2012, APA’s Council of Representatives will consider adopting the resolution as APA policy.

Preston Britner, PhD, a child developmental psychologist and professor at the University of Connecticut, helped draft the proposed resolution as co-chair of CYF. “It addresses the concerns about physical punishment and a growing body of research on alternatives to physical punishment, along with the idea that psychology and psychologists have much to contribute to the development of those alternative strategies,” he says.

More than three decades have passed since APA approved a resolution in 1975 opposing corporal punishment in schools and other institutions, but it didn’t address physical discipline in the home. That resolution stated that corporal punishment can “instill hostility, rage and a sense of powerlessness without reducing the undesirable behavior.”

Research findings

Physical punishment can work momentarily to stop problematic behavior because children are afraid of being hit, but it doesn’t work in the long term and can make children more aggressive, Graham-Bermann says.

A study published last year in Child Abuse and Neglect revealed an intergenerational cycle of violence in homes where physical punishment was used. Researchers interviewed parents and children age 3 to 7 from more than 100 families. Children who were physically punished were more likely to endorse hitting as a means of resolving their conflicts with peers and siblings. Parents who had experienced frequent physical punishment during their childhood were more likely to believe it was acceptable, and they frequently spanked their children. Their children, in turn, often believed spanking was an appropriate disciplinary method.

The negative effects of physical punishment may not become apparent for some time, Gershoff says. “A child doesn’t get spanked and then run out and rob a store,” she says. “There are indirect changes in how the child thinks about things and feels about things.”

As in many areas of science, some researchers disagree about the validity of the studies on physical punishment. Robert Larzelere, PhD, an Oklahoma State University professor who studies parental discipline, was a member of the APA task force who issued his own minority report because he disagreed with the scientific basis of the task force recommendations. While he agrees that parents should reduce their use of physical punishment, he says most of the cited studies are correlational and don’t show a causal link between physical punishment and long-term negative effects for children.

Robert Larzelere, PhD, an Oklahoma State University professor who studies parental discipline, was a member of the APA task force who issued his own minority report because he disagreed with the scientific basis of the task force recommendations. While he agrees that parents should reduce their use of physical punishment, he says most of the cited studies are correlational and don’t show a causal link between physical punishment and long-term negative effects for children.

“The studies do not discriminate well between non-abusive and overly severe types of corporal punishment,” Larzelere says. “You get worse outcomes from corporal punishment than from alternative disciplinary techniques only when it is used more severely or as the primary discipline tactic.”

In a meta-analysis of 26 studies, Larzelere and a colleague found that an approach they described as “conditional spanking” led to greater reductions in child defiance or anti-social behavior than 10 of 13 alternative discipline techniques, including reasoning, removal of privileges and time out (Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2005). Larzelere defines conditional spanking as a disciplinary technique for 2- to 6-year-old children in which parents use two open-handed swats on the buttocks only after the child has defied milder discipline such as time out.

Larzelere defines conditional spanking as a disciplinary technique for 2- to 6-year-old children in which parents use two open-handed swats on the buttocks only after the child has defied milder discipline such as time out.

Gershoff says all of the studies on physical punishment have some shortcomings. “Unfortunately, all research on parent discipline is going to be correlational because we can’t randomly assign kids to parents for an experiment. But I don’t think we have to disregard all research that has been done,” she says. “I can just about count on one hand the studies that have found anything positive about physical punishment and hundreds that have been negative.”

Teaching new skills

If parents aren’t supposed to hit their kids, what nonviolent techniques can help with discipline? The Parent Management Training program headed by Kazdin at Yale is grounded in research on applied behavioral analysis. The program teaches parents to use positive reinforcement and effusive praise to reward children for good behavior.

Kazdin also uses a technique that may sound like insanity to most parents: Telling toddlers to practice throwing a tantrum. Parents ask their children to have a pretend tantrum without one undesirable element, such as hitting or kicking. Gradually, as children practice controlling tantrums when they aren’t angry, their real tantrums lessen, Kazdin says.

Remaining calm during a child’s tantrums is the best approach, coupled with time outs when needed and a consistent discipline plan that rewards good behavior, Graham-Bermann says. APA offers the Adults & Children Together Against Violence program, which provides parenting skills classes through a nationwide research-based program called Parents Raising Safe Kids. The course teaches parents how to avoid violence through anger management, positive child discipline and conflict resolution. (For more information on ACT, see the November Monitor.)

Parents should talk with their children about appropriate means of resolving conflicts, Gershoff says. Building a trusting relationship can help children believe that discipline isn’t arbitrary or done out of anger.

Building a trusting relationship can help children believe that discipline isn’t arbitrary or done out of anger.

“Part of the problem is good discipline isn’t quick or easy,” she says. “Even the best of us parents don’t always have that kind of patience.”

Brendan L. Smith is a writer in Washington, D.C.

Scientists have found out how corporal punishment affects children's brain

Corporal punishment, including spanking, lead to changes in the child's brain, British experts warn. In children whose parents use such parenting measures, the brain reacts to the threat in the same way as those who were subjected to more serious abuse. In the long term, this increases the risk of developing mental disorders.

Harvard scientists have warned of the dangers of physical punishment for children - even spanking can lead to brain changes that cause depression, anxiety disorders and behavioral disorders. The study was published in the journal Child Development .

According to the authors of the study, corporal punishment is associated with the development of anxiety disorders, depression, behavioral problems and cravings for substance use.

Recent studies also show that about half of parents (at least among Americans) spanked their children during the year, and a third in the last week. However, the relationship between spanking and brain activity has not been previously studied.

“We know that children in families with corporal punishment are more likely to develop anxiety, depression, behavioral problems and other mental health problems, but many people do not consider spanking a form of abuse,” says Cathy McLaughlin, lead author of the study. . “In this study, we wanted to explore whether spanking affects brain development.”

McLaughlin and colleagues analyzed data from a large study of child development, focusing on 147 children aged 10-11 who were spanked and a control group who were not physically punished. While in the MRI, the children looked at pictures of the actors, with a neutral expression or intimidating. The tomograph recorded the brain activity that arose in response to a particular face, and the researchers compared the brain activity of both groups.

While in the MRI, the children looked at pictures of the actors, with a neutral expression or intimidating. The tomograph recorded the brain activity that arose in response to a particular face, and the researchers compared the brain activity of both groups.

“On average, fearful faces caused more activation in different areas of the brain than neutral ones,” the researchers note. “However, children who were spanked showed more activation in certain regions of the prefrontal cortex than children who were not spanked.”

Moreover, scientists did not find a significant difference in the brain response of spanked children and abused children.

"Although we may not consider corporal punishment a form of abuse, in terms of how a child's brain reacts, it makes no difference," says McLaughlin.

This study is the first step towards further interdisciplinary analysis of the potential impact of spanking and other corporal punishment on children's brain development and life experience, the authors note.

“These results are consistent with predictions of the potential consequences of corporal punishment made in other areas such as developmental psychology, social work,” says George Cuartas, co-author of the study. “By identifying the brain patterns associated with the consequences of corporal punishment, we can say that this type of punishment can be detrimental to children, and we have more opportunities to study it.”

However, one should not extend their conclusions to each individual child, the researchers emphasize.

“It's important to keep in mind that corporal punishment doesn't affect every child the same, and children can be resilient when faced with adversity,” Cuartas says. “The bottom line is that corporal punishment carries a risk that can translate into child developmental problems, and to prevent this, parents and policy makers should work to try to reduce its prevalence.”

We hope that these findings can encourage families to move away from corporal punishment, opening people's eyes to potential negative consequences that they may not have thought about before,” concludes McLaughlin.

Yelling and other harsh parenting practices also harm children's brain development, University of Montreal researchers warn. They found out that children who were shaken, beaten, yelled at and vented had a smaller amygdala and prefrontal cortex by age 12-16 compared with peers who did not encounter such behavior from their parents.

Sexual and physical violence lead to the same consequences, scientists note.

Apparently, there is no difference for the child's brain - it reacts to all manifestations of rudeness and threats with changes that increase the risk of mental disorders in the future.

Corporal punishment and health

Corporal punishment and health- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Т

- У

- Ф

- Х

- Ц

- Ч

- Ш

- Щ

- Ъ

- Ы

- Ь

- Э

- Ю

- Я

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Latest information

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO Data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Corporal punishment and health

Basic Facts

- Corporal or physical punishment is widespread throughout the world and is practiced both at home and in schools.

Approximately 60% of children aged 2-14 are regularly subjected to corporal punishment by their parents or other caregivers. In some countries, schoolchildren almost universally report experiencing corporal punishment at the hands of school personnel. The risk of corporal punishment is about equally threatening for boys and girls, as well as children from wealthy and poor families.

Approximately 60% of children aged 2-14 are regularly subjected to corporal punishment by their parents or other caregivers. In some countries, schoolchildren almost universally report experiencing corporal punishment at the hands of school personnel. The risk of corporal punishment is about equally threatening for boys and girls, as well as children from wealthy and poor families. - Evidence suggests that corporal punishment exacerbates behavioral problems in children over time and has no positive consequences.

- All forms of corporal punishment, however mild and harmless, inevitably carry the risk of escalation. Parents who use corporal punishment are more likely to engage in particularly cruel forms of child abuse, according to research.

- Across countries and cultures, there is an association between corporal punishment and targets for a range of adverse outcomes for children, including physical and mental health damage, impaired cognitive, social and emotional development, poor educational achievement, increased aggressiveness and violent behavior.

- Corporal punishment is a violation of the child's rights to physical integrity and human dignity, health, development, education and freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Ending violence against children is part of several targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but most explicitly is target 16.2: “End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence and torture in relation to children."

- Corporal punishment and its harmful effects can be prevented through a multi-sectoral and multi-pronged approach that includes reforming laws, changing harmful perceptions about parenting and punishment of children, providing support to parents and caregivers of children, and implementing school-based programmes.

General information

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, which monitors compliance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, defines the "bodily" or "physical" punishment as "any punishment in which physical force is used and which is intended to inflict some degree of pain or discomfort, however mild".

From the point of view of the Committee, such punishments in most cases take the form of hitting (spanking, spanking, spanking) on children with a hand or some object (whip, stick, belt, shoe, wooden spoon, etc.), but may also to be in kicks, shaking or throwing children, scratching, pinching, biting, hair pulling or smacking, forcing children to remain in an uncomfortable position, burning, scalding or forced swallowing.

There are other non-physical forms of punishment which are also cruel and degrading and as such are incompatible with the Convention. These include, for example, punishment by humiliation, insult, slander, Making children the subject of bullying, using threats, intimidation or ridicule of a child.

Magnitude of the problem

According to data collected by UNICEF from 2005 to 2013 in nationally representative surveys in 56 countries, approximately six out of 10 children aged 2 to 14 years have experienced corporal punishment in the past month by parents at home.

On average, 17% of children have experienced severe punishment with physical force (blows to the head, slaps, slaps or hard repeated blows), but in some countries this figure exceeds 40%. Significant discrepancies in indicators between countries and regions indicate the possibility of preventing such events.

On average, 17% of children have experienced severe punishment with physical force (blows to the head, slaps, slaps or hard repeated blows), but in some countries this figure exceeds 40%. Significant discrepancies in indicators between countries and regions indicate the possibility of preventing such events. Comparable surveys show that the prevalence of corporal punishment of boys and girls is about the same, apart from some countries that have higher rates of punishment for boys. Children younger children (ages 2-4) are subjected to physical punishment, including cruelty, just as frequently as older children (ages 5-14) and more frequently in some countries. Physical disciplinary methods effects are applied even to the youngest children; according to comparable surveys conducted in 2012–2016. at 29countries, three out of 10 children aged 12-23 months are spanked.

Most children are subjected to both physical and psychological forms of punishment. Many parents and caregivers admit to using non-violent discipline measures (for example, explaining to the child why his behavior is wrong, or depriving the child of benefits or pleasures), but such measures are usually used in combination with physical methods.

Children who are subjected exclusively to non-violent forms of discipline are a minority.

Children who are subjected exclusively to non-violent forms of discipline are a minority. One in two children aged 6-17 (732 million) live in a country that does not have a total ban on corporal punishment in schools. Studies have found that in Africa and Central America, the proportion of people who have ever lifetime experience of corporal punishment in life education institutions is above 70%, the proportion of those subjected to such punishment in the last year is more than 60% in the WHO regions for the Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asia, and the proportion more than 40% in Africa and South-East Asia who were subjected to corporal punishment in the last week. Lower rates are reported in the WHO Western Pacific Region, where prevalence rates for corporal punishment throughout life and over the last year amounted to approximately 25%. Physical punishment appears to be widespread at both the primary and secondary school levels.

Consequences

Corporal punishment provokes destructive psychological and physiological reactions.

Children not only experience pain, depression, fear, anger, shame and guilt, but also physiological stress, in which a sense of threat leads to the activation of conductive pathways of the nervous system responsible for the response to danger. In children who have experienced punishment with the use of physical force, vegetative reactivity to stress is often increased, body systems are overloaded, including nervous, cardiovascular and metabolic systems, and there are changes in the structure and functioning of the brain.

Children not only experience pain, depression, fear, anger, shame and guilt, but also physiological stress, in which a sense of threat leads to the activation of conductive pathways of the nervous system responsible for the response to danger. In children who have experienced punishment with the use of physical force, vegetative reactivity to stress is often increased, body systems are overloaded, including nervous, cardiovascular and metabolic systems, and there are changes in the structure and functioning of the brain. Despite the widespread belief that spanking is acceptable, this educational practice also leads to atypical brain changes comparable to those caused by serious abuse, and this refutes the oft-repeated argument that less severe forms of physical punishment do no harm.

A large body of research confirms the relationship between corporal punishment and a wide range of negative short- and long-term effects, such as:

- direct bodily harm, sometimes resulting in severe impairment, permanent disability or death;

- psychiatric disorders, including behavioral and anxiety disorders, depression, hopelessness, low self-esteem, self-harm and suicide attempts, alcohol and drug addiction, hostility and emotional instability, which may continue into adulthood;

- delays in cognitive, social and emotional development, especially in emotion regulation and conflict resolution skills;

- negative impact on education, including dropping out of school and reduced performance and career prospects;

- difficult development of moral standards and increased antisocial behavior;

- increased levels of aggression in children;

- violent, antisocial and illegal behavior in adulthood;

- collateral health damage resulting from overload of body systems, including the development of cancer, alcohol problems, migraine, cardiovascular disease, arthritis and obesity in childhood and adulthood;

- increased tolerance and tendency to other forms of violence; and

- dysfunctional family relationships.

There is some evidence that the response to corporal punishment depends on its intensity; studies have found that with an increase in the frequency of corporal punishment, the level of child aggression and poor performance in mathematics and reading increases.

Risk factors

There are no large differences in the prevalence of corporal punishment by sex or age, although boys and younger children are more at risk in some cases. Children with disabilities are more likely than healthy children subjected to physical punishment. Parents who were physically punished as children are more likely to use physical force against their own children.

In most countries for which data are available, children from wealthier and poorer backgrounds are equally at risk of violent discipline. On the other hand, in some resource-poor countries, especially after the rapid expansion of the education system, the increased workload on teachers, caused by a lack of human and material resources, can provoke an increase in the practice of corporal punishment in the classroom.

Prevention and suppression of corporal punishment

INSPIRE's suite of technical measures provides several effective and promising solutions to the problem, including:

- enacting and enforcing legislation to prohibit physical punishment. Such legislation provides equal protection for children from abuse by adults and is educational rather than punitive. function, with the aim of raising awareness, shaping attitudes towards non-violent methods of raising children and explaining the responsibilities of parents in caring for children;

- norms and values change programs aimed at changing harmful norms accepted in society regarding the upbringing of children and teaching them to discipline;

- support for parents and caregivers by disseminating information and conducting practical trainings on the development of caring and non-violent parenting skills;

- learning and life skills activities to create a supportive and violence-free school environment and strengthen relationships between students, teachers and administrative staff;

- response and support to identify affected children and their families in a timely manner and prevent recurrence of violent disciplinary methods and reduce their consequences.

The sooner the child is covered by these measures, the greater the benefits for the child (in particular, in terms of cognitive development, the formation of behavioral and social competencies, educational achievements) and for society (in particular, in the form of a decrease in the level of crime among minors and adults).

WHO activities

WHO is implementing a range of comprehensive measures to address the issue of corporal punishment. In collaboration with partners, WHO provides guidance and technical support on the application of evidence-based methods to prevent and combat corporal punishment. The prevention of corporal punishment is facilitated by the implementation of several strategies included in the INSPIRE set of technical measures, including those on legislation, norms and values, parental behavior and the prevention of school violence. The 2020 Global Status Report on the Prevention of Violence against Children provides information on the progress countries have made in implementing legislation and programs to help reduce the occurrence of violence against children.