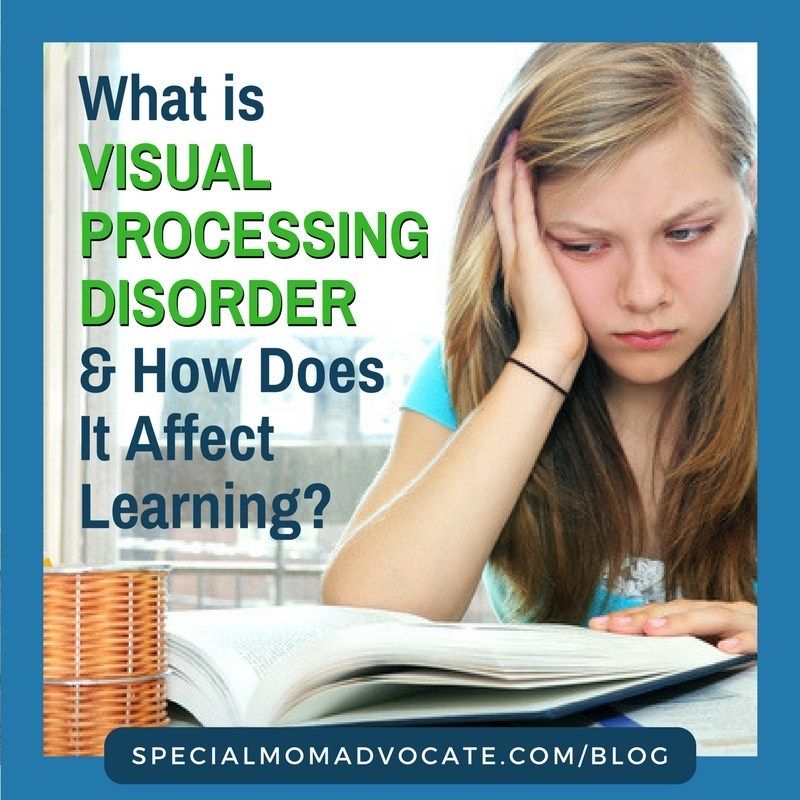

How do i get my child tested for sensory processing disorder

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) - familydoctor.org

What is sensory processing disorder?

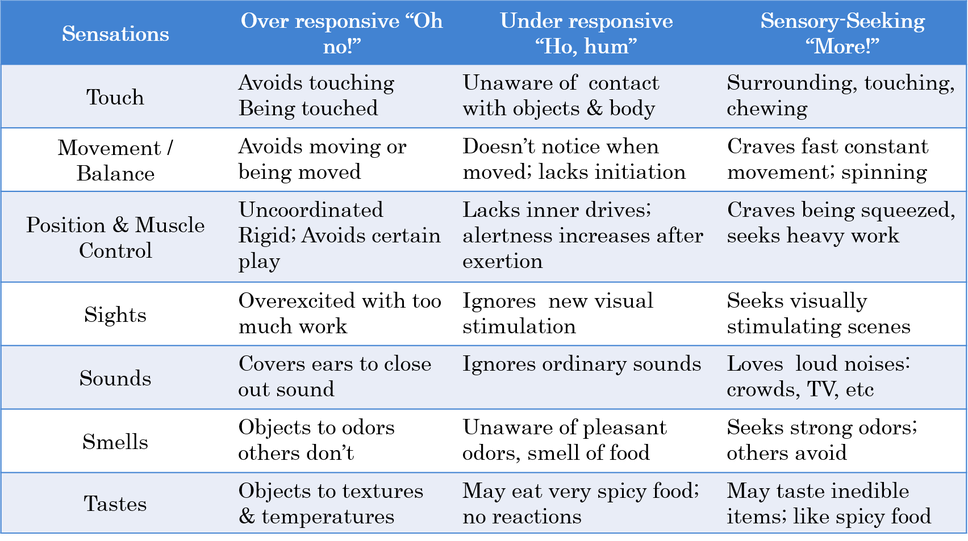

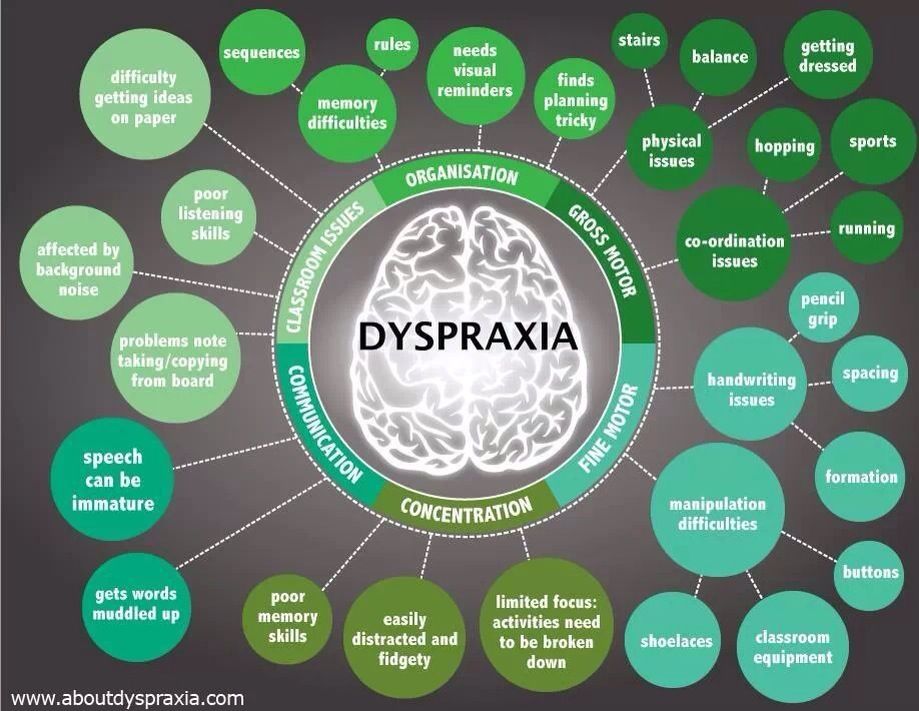

Sensory processing disorder (SPD) is a condition that affects how your brain processes sensory information (stimuli). Sensory information includes things you see, hear, smell, taste, or touch. SPD can affect all of your senses, or just one. SPD usually means you’re overly sensitive to stimuli that other people are not. But the disorder can cause the opposite effect, too. In these cases, it takes more stimuli to impact you.

Children are more likely than adults to have SPD. But adults can have symptoms, too. In adults, it’s likely these symptoms have existed since childhood. However, the adults have developed ways to deal with SPD that let them hide the disorder from others.

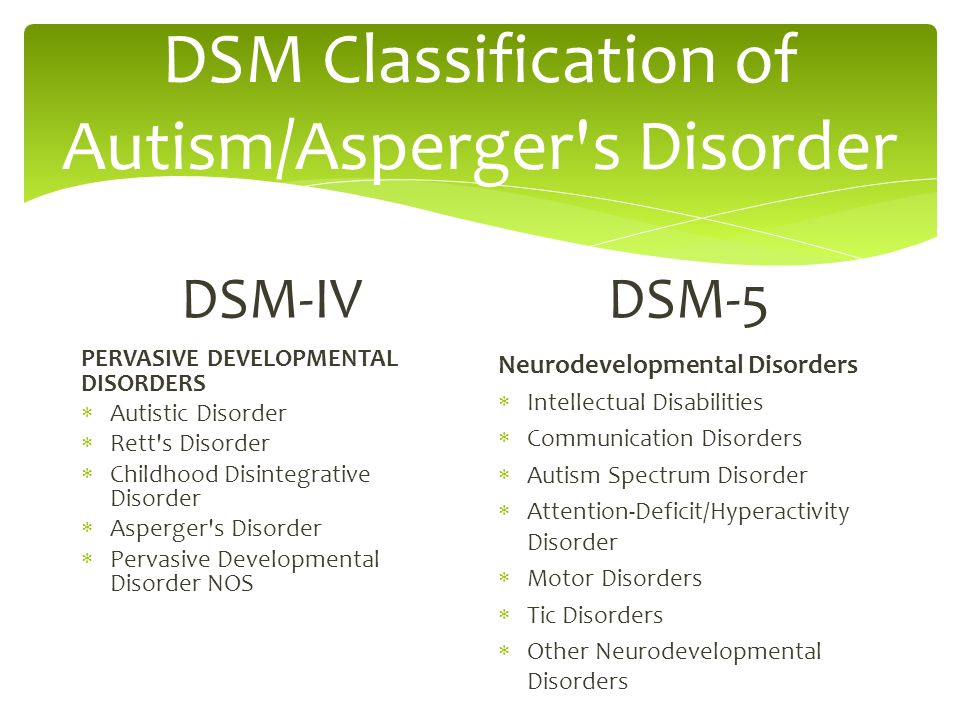

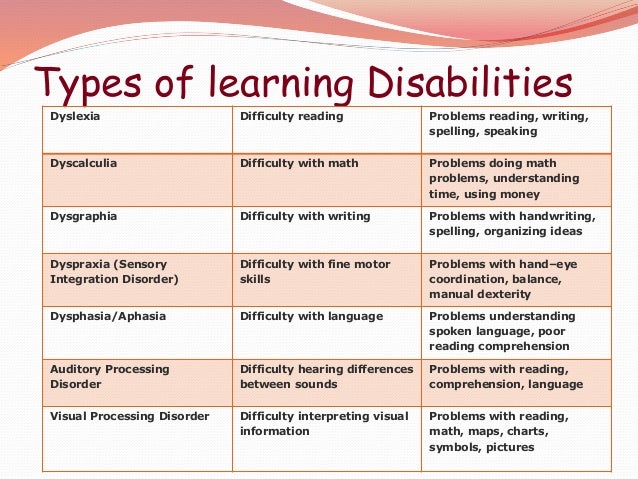

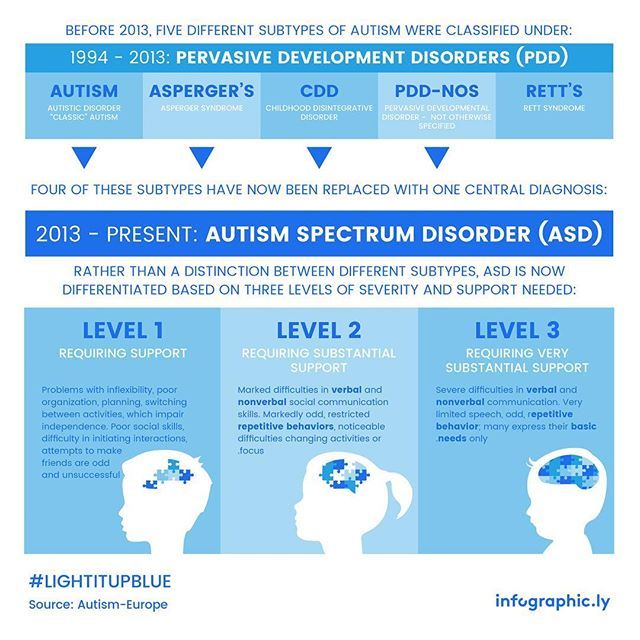

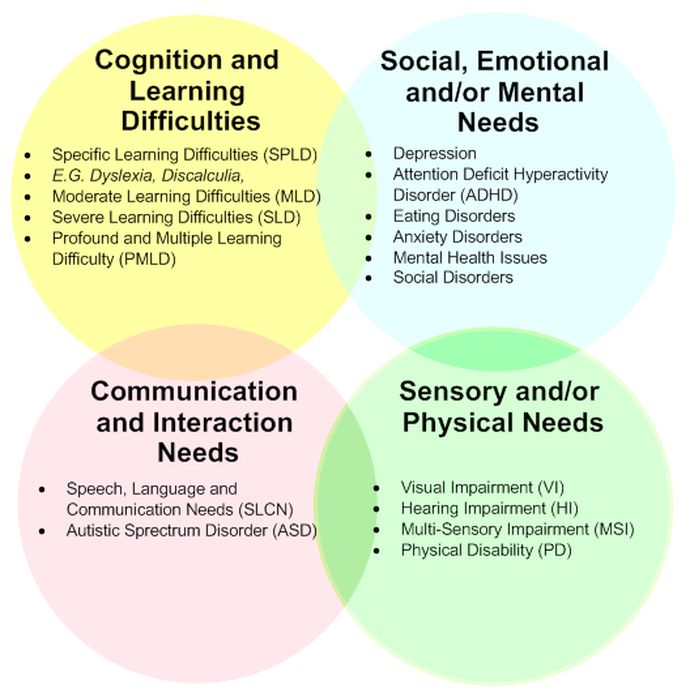

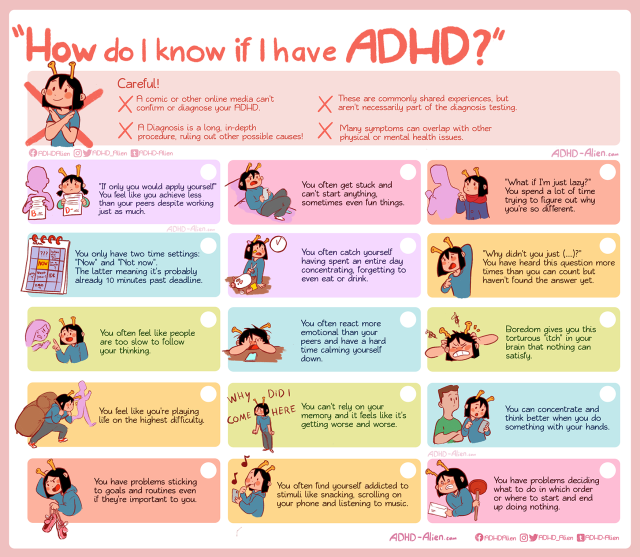

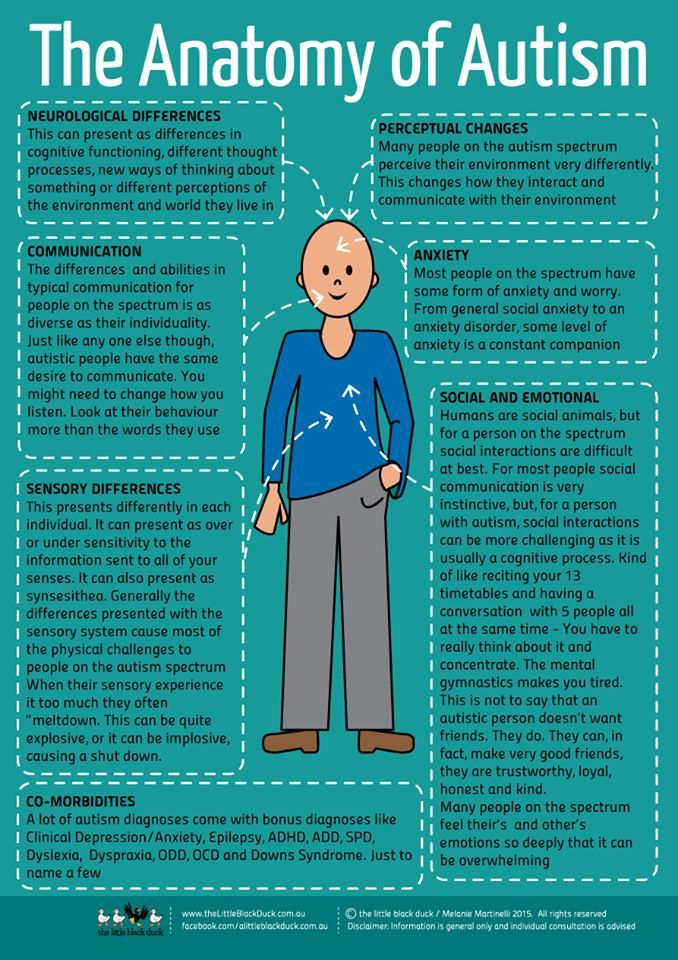

There is some debate among doctors about whether SPD is a separate disorder. Some doctors argue it isn’t. Some say it’s a diagnosis for things that could be explained as common behavior for children. Others say some children are just highly sensitive. Some doctors say that SPD is a symptom of other disorders — such as autism spectrum disorder, hyperactivity, attention deficit disorder, anxiety, etc. — and not a disorder itself. Other doctors believe your child may suffer from SPD without having another disorder. Some say it’s clear that some children have trouble handling regular sensory information (stimuli). For now, SPD isn’t recognized as an official medical diagnosis.

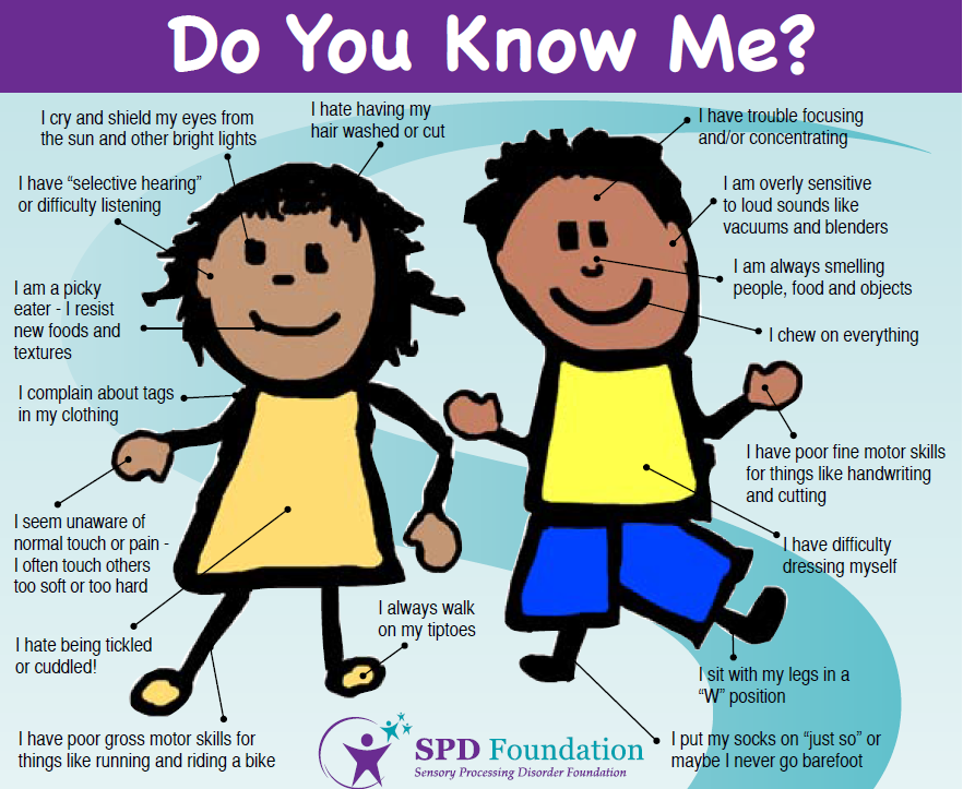

Symptoms of sensory processing disorder

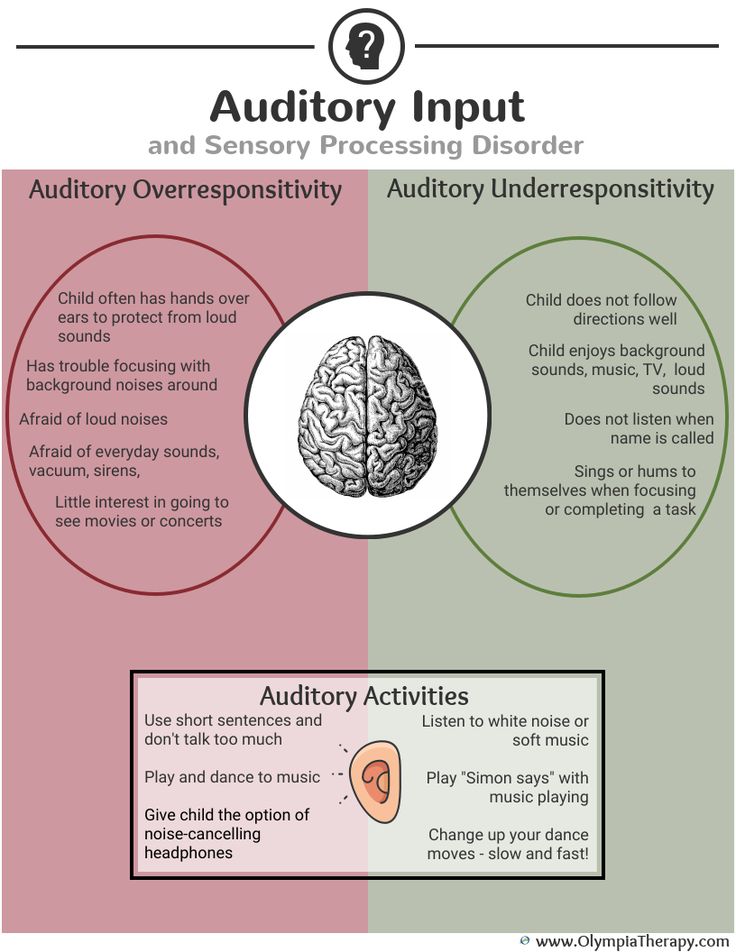

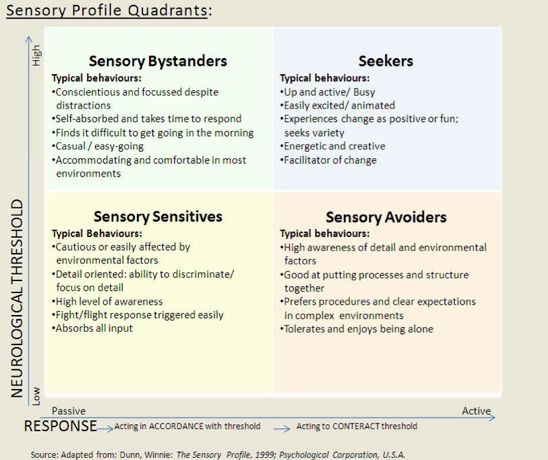

SPD can affect one sense or multiple senses. Children who have SPD may overreact to sounds, clothing, and food textures. Or they may underreact to sensory input. This causes them to crave more intense thrill-seeking stimuli. Some examples include jumping off tall things or swinging too high on the playground. Also, children with SPD are not always just one or the other. They can be a mixture of oversensitive and under-sensitive.

Children may be oversensitive if they:

- Think clothing feels too scratchy or itchy.

- Think lights seem too bright.

- Think sounds seem too loud.

- Think soft touches feel too hard.

- Experience food textures make them gag.

- Have poor balance or seem clumsy.

- Are afraid to play on the swings.

- React poorly to sudden movements, touches, loud noises, or bright lights.

- Have behavior problems.

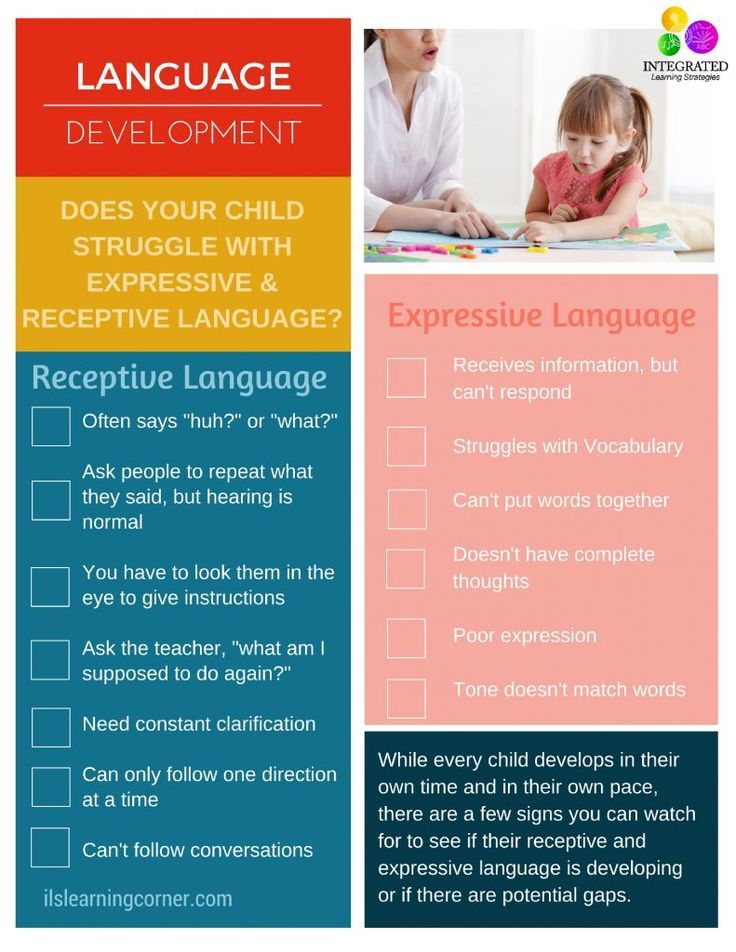

Sometimes these symptoms are linked to poor motor skills as well. Your child may have trouble holding a pencil or scissors. He or she may have trouble climbing stairs or have low muscle tone. He or she also may have language delays.

In an older children, these symptoms may cause low self-confidence. They may lead to social isolation and even depression.

Children may be under-sensitive (sensory-seeking) if they:

- Can’t sit still

- Seek thrills (loves jumping, heights, and spinning).

- Can spin without getting dizzy.

- Don’t pick up on social cues.

- Don’t recognize personal space.

- Chew on things (including their hands and clothing).

- Seek visual stimulation (like electronics).

- Have problems sleeping.

- Don’t recognize when their face is dirty or nose is running.

What causes sensory processing disorder?

Doctors don’t know what causes SPD. They’re exploring a genetic link, which means it could run in families. Some doctors believe there could be a link between autism and SPD. This could mean that adults who have autism could be more likely to have children who have SPD. But it’s important to note that most people who have SPD don’t have autism.

How is sensory processing disorder diagnosed?

Parents may recognize their child’s behavior is not typical. But most parents may not know why. Don’t be afraid to discuss your child’s behavior with your doctor. He or she may refer you to an occupational therapist. These professionals can assess your child for SPD. He or she will likely watch your child interact in certain situations. The therapist will ask your child questions. All of these things will help make a diagnosis.

The therapist will ask your child questions. All of these things will help make a diagnosis.

Can sensory processing disorder be prevented or avoided?

SPD can’t be prevented or avoided because doctors don’t know what causes it.

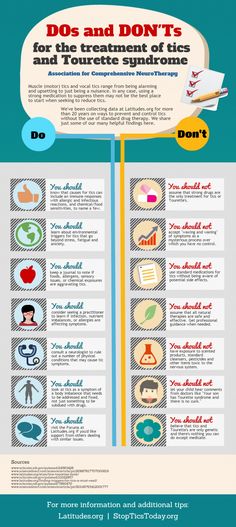

Sensory processing disorder treatment

Treatment is usually done through therapy. Research shows that starting therapy early is key for treating SPD. Therapy can help children learn how to manage their challenges.

Therapy sessions are led by a trained therapist. He or she will help you and your child learn how to cope with the disorder. Sessions are based on if your child is oversensitive, under-sensitive, or a combination of both.

There are different types of therapy:

Sensory integration therapy (SI). This type of therapy uses fun activities in a controlled environment. With the therapist, your child experiences stimuli without feeling overwhelmed. He or she can develop coping skills for dealing with that stimuli. Through this therapy, these coping skills can become a regular, everyday response to stimuli.

Through this therapy, these coping skills can become a regular, everyday response to stimuli.

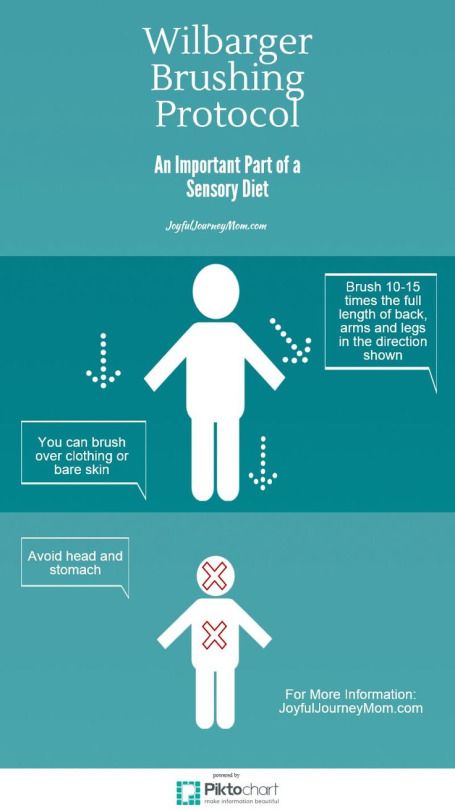

Sensory diet. Many times, a sensory diet will supplement other SPD therapies. A sensory diet isn’t your typical food diet. It’s a list of sensory activities for home and school. These activities are designed to help your child stay focused and organized during the day. Like SI, a sensory diet is customized based on your child’s needs. A sensory diet at school might include:

- A time every hour when your child could go for a 10-minute walk.

- A time twice a day when your child could swing for 10 minutes.

- Access to in-class headphones so your child can listen to music while working.

- Access to fidget toys.

- Access to a desk chair bungee cord. This gives your child a way to move his or her legs while sitting in the classroom.

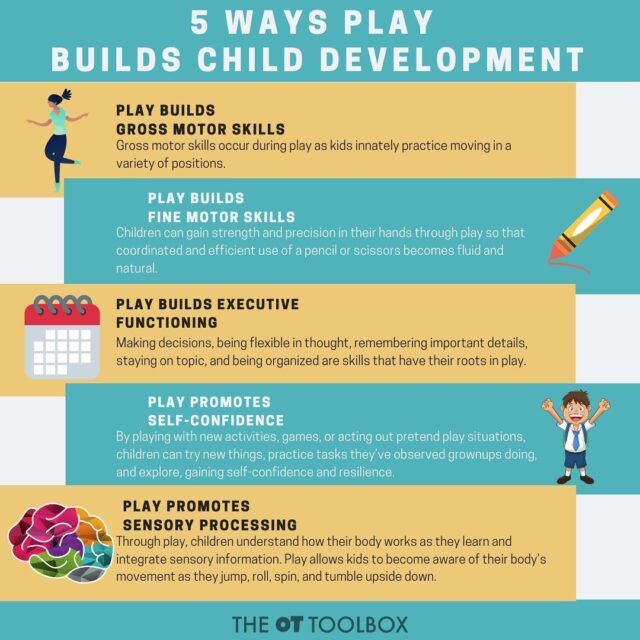

Occupational therapy. Your child also may need this therapy to help with other symptoms related to SPD. It can help with fine motor skills, such as handwriting and using scissors. It also can help with gross motor skills, such as climbing stairs and throwing a ball. It can teach everyday skills, such as getting dressed and how to use utensils.

It can help with fine motor skills, such as handwriting and using scissors. It also can help with gross motor skills, such as climbing stairs and throwing a ball. It can teach everyday skills, such as getting dressed and how to use utensils.

Check your insurance

Talk to your doctor about how a therapist fits in your health insurance. Many times, insurance won’t pay for therapies used to treat SPD. That’s because SPD isn’t yet recognized as an official disorder.

Living with sensory processing disorder

Living with SPD can be hard. Parents of children with SPD can feel alone. They may avoid taking their child out in public to avoid sensory overload. Parents may also feel like they need to make excuses for their child’s behavior.

Adults who have SPD may feel isolated, too. Sensory overload can prevent them from leaving the house. This can make it difficult to go to the store or even to work.

Adults who are struggling with SPD should work with an occupational therapist. The therapist may be able to help them learn new reactions to stimuli. This can lead to changes in how they deal with certain situations. And that may lead to an improved lifestyle.

The therapist may be able to help them learn new reactions to stimuli. This can lead to changes in how they deal with certain situations. And that may lead to an improved lifestyle.

Sometimes, even if SPD gets better with therapy or age, it may never go away. A major life event or stress can trigger symptoms.

Questions to ask your doctor

- How can I determine whether I have/my child has SPD?

- I have/my child has SPD. Now what?

- How can I help my young child have fun at the playground if he or she has SPD?

- Can my child live a normal life?

- How might my child react to certain stimuli?

- Will SPD go away as my child gets older?

- Are there any medicines that help SPD?

- Can you help me find out if my insurance will cover therapy?

Symptoms & Signs in Children

What Is Sensory Processing Disorder?

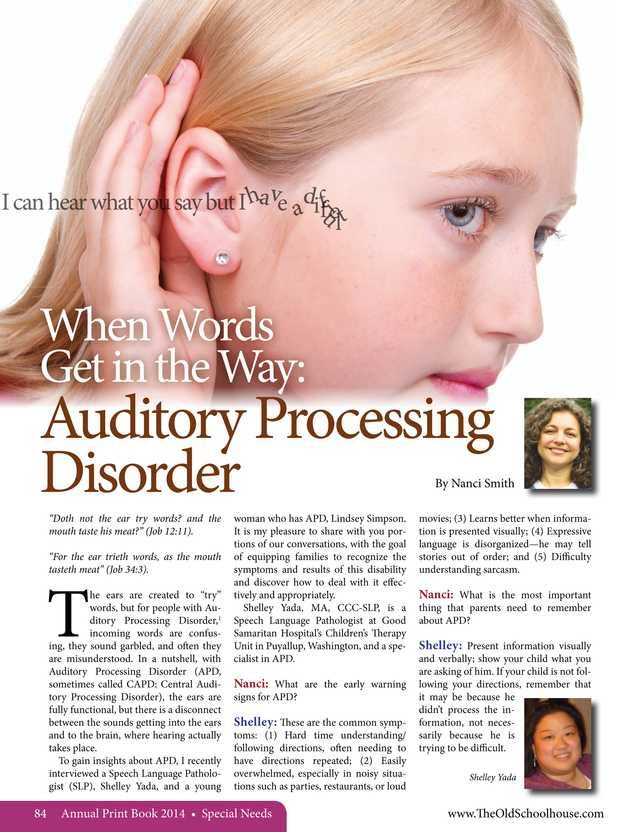

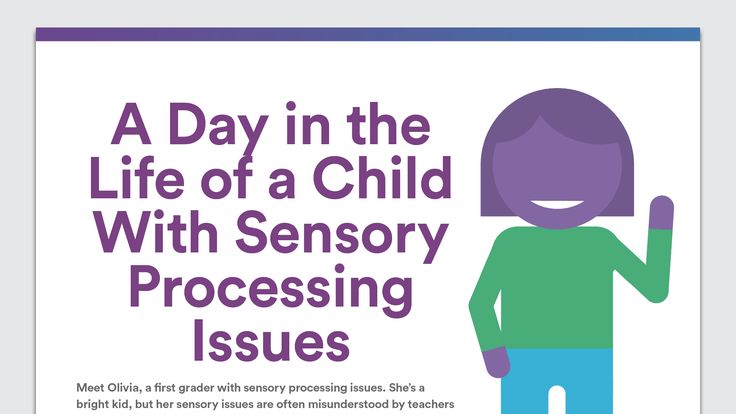

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) — formerly referred to as sensory integration dysfunction — is a neurological condition that interferes with the body’s ability to interpret sensory messages from the brain and convert those messages into appropriate motor and behavioral responses. It's not uncommon to feel occasional sensory overload — that is, to feel overwhelmed by distracting noises or crowded spaces or strong odors once in a while — but for children with SPD, these sensations disrupt and overwhelm everyday life.

It's not uncommon to feel occasional sensory overload — that is, to feel overwhelmed by distracting noises or crowded spaces or strong odors once in a while — but for children with SPD, these sensations disrupt and overwhelm everyday life.

Sensory Processing Disorder may make it difficult to filter out unimportant sensory information, like the background noise of a busy school hallway, and causes children to feel overwhelmed and over-stimulated in certain environments. Or SPD may make it difficult to take in important sensory information; a child who has tripped may not react quickly enough to soften her fall, for example. In addition, SPD may make it difficult to pinpoint the source of bodily pain or gauge the appropriate pressure to use when writing with a pencil. SPD may make children feel that their bodies are uncooperative, that they always disappoint others, and that they are failures.

What Are the Symptoms of Sensory Processing Disorder in Children?

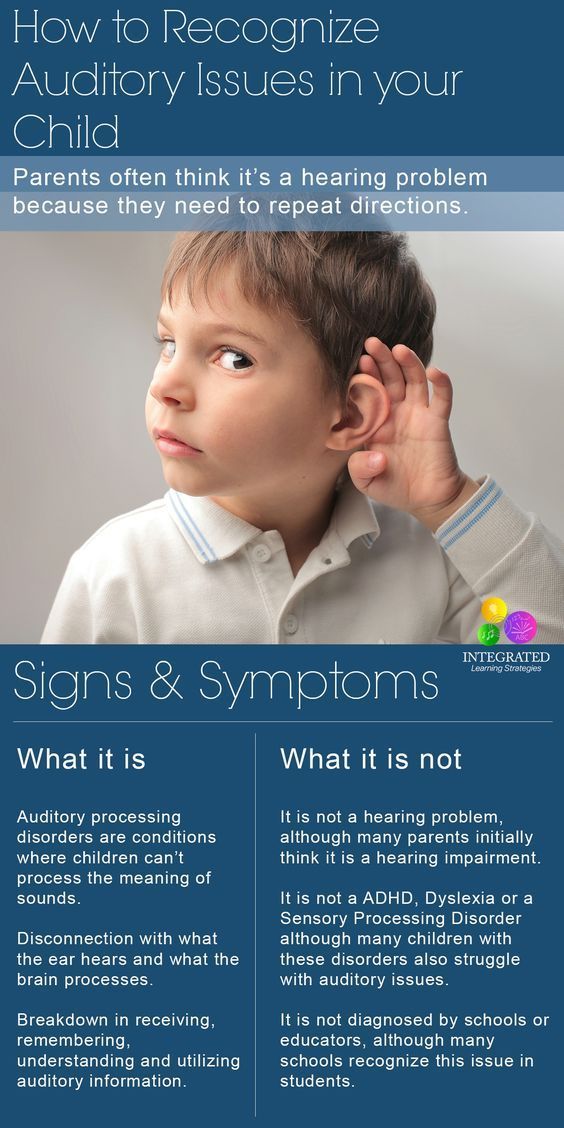

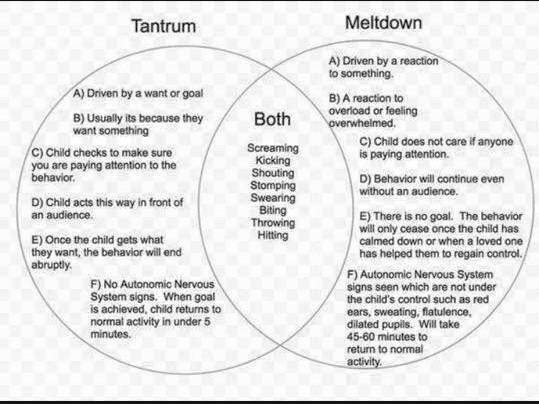

These emotions may manifest as anxiety or temper tantrums or meltdowns — all reactions that may understandably be mistaken for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). But if your child gets upset consistently in the same noisy or smelly environment, or when asked to eat the same specific foods as other kids, or when bothered by itchy tags in his clothing, or when frustrated figuring out how to orient his body to get dressed, he may be dealing with SPD.

But if your child gets upset consistently in the same noisy or smelly environment, or when asked to eat the same specific foods as other kids, or when bothered by itchy tags in his clothing, or when frustrated figuring out how to orient his body to get dressed, he may be dealing with SPD.

Other children with SPD crave activities that will stimulate their senses. This could entail riding a bicycle too fast down a steep hill or performing flips on the monkey bars — daredevil acts that could, likewise, look a lot like ADHD hyperactivity. Another difficulty is poor discrimination of sensations. Is the water hot or cold? Is this the right buttonhole? Has the steak been chewed sufficiently before swallowing? Did someone say "Go" or "No?" Is that word "bug" or "dug?" These kids may have sensory processing challenges, not attentional issues.

In the self-test below, select the statement that most accurately describes your child's behavior and share the results with your child’s physician.

Adapted from the SPD checklist from the STAR Institute for Sensory Processing Disorder. This is not a diagnostic tool. An occupational therapist trained in sensory integration is the best professional to make an accurate diagnosis through clinical evaluation.

I have to buy tagless, itchless clothes for my child – the looser the better.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

Thunderstorms terrify my child. The loud booms and cracks send them cowering under the blankets.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child spits out foods like cooked peas or bananas pieces if they’re the slightest bit mushy.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child has too much trouble fastening buttons and tying laces, and prefers to wear "easier" items like zip-up sweatshirts and Velcro sneakers.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child loves salsa (the hotter the better) and drinks pickle juice right out of the jar.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

School picture day sends my child home in tears every year. The camera flashes hurt their sensitive eyes.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child gets in trouble in gym class for tackling during flag football.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child is bothered by anything slimy or sticky on his fingers, like paint.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child gags when trying to swallow a pill. They prefer liquid antibiotics and chewable vitamins.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child refuses to change for gym class, saying the locker room is too stinky.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child loves amusement park rides, but can’t tolerate the long lines and crowds.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child has poor balance and coordination, and tends to trip over their own feet. Keeping up with other kids in games like jumping rope and climbing trees can be difficult.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child complains about being barefoot in the sand when at the beach.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child prefers to go on one ride at the carnival, like the merry-go-round, over and over.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

I have to use unscented detergent. Washing my child's sheets with any scent leads to a meltdown.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

Bath time can be difficult. My child hates being sprayed with water and having their hair combed before bed, which leads to tantrums.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

My child dislikes buying lunch at school and complains about being grossed out. Even seeing apple sauce on their tray as dessert gives them the heeby jeebies.

Very Often

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

(Optional) Receive your Sensory Processing Disorder Symptom Test results — plus more helpful resources — via email from ADDitude.

Subscribe me to your newsletter!

Can’t see the Sensory Processing Disorder symptoms test above? Click here to open this test in a new window.

Sensory Processing Disorder in Children: Next Steps

1. Take This Test: Does My Child Have ADHD?

2. Take This Test: Oppositional Defiant Disorder in Children

3. Take This Test: Executive Function Disorder in Children

4. Research Treatments for Sensory Processing Disorder

5. Read “I’m Overloaded!” Responding to Sensory Dysfunction

Previous Article Next Article

Heightened Senses: Sensory Processing Disorders in Children

08/07/16

Some children suffer from hypersensitivity to sounds, lights or touch, while others barely react to them. Studies of these disorders may help to better understand autism When his mom, Lori, can't find something, she asks her 12-year-old son to "look inside his head," and in his huge catalog of visual information, he finds the right thing without difficulty. His amazing memory for faces allows him to recognize someone he has only seen once in his life, even in a crowd of strangers. Keen hearing allows him to perfectly imitate voices. Ask him to sing something from the Beatles and he will ask if he should sing Lennon-style or McCartney-style. nine0003

Studies of these disorders may help to better understand autism When his mom, Lori, can't find something, she asks her 12-year-old son to "look inside his head," and in his huge catalog of visual information, he finds the right thing without difficulty. His amazing memory for faces allows him to recognize someone he has only seen once in his life, even in a crowd of strangers. Keen hearing allows him to perfectly imitate voices. Ask him to sing something from the Beatles and he will ask if he should sing Lennon-style or McCartney-style. nine0003

But as superhero stories say, with great power comes great hardship. Playground parties, popular among his suburban Atlanta peers, are more torture than entertainment for him. Too noisy, too crowded, too much stimulation. Jack has such sensitive hearing that he cannot eat at the same table as his family because the sound and sight of his parents chewing can make him vomit. As a baby, he didn't sleep for more than four hours straight, and his mother had to keep him upright all the time, hugging him to her chest and putting her hand on his head. nine0003

nine0003

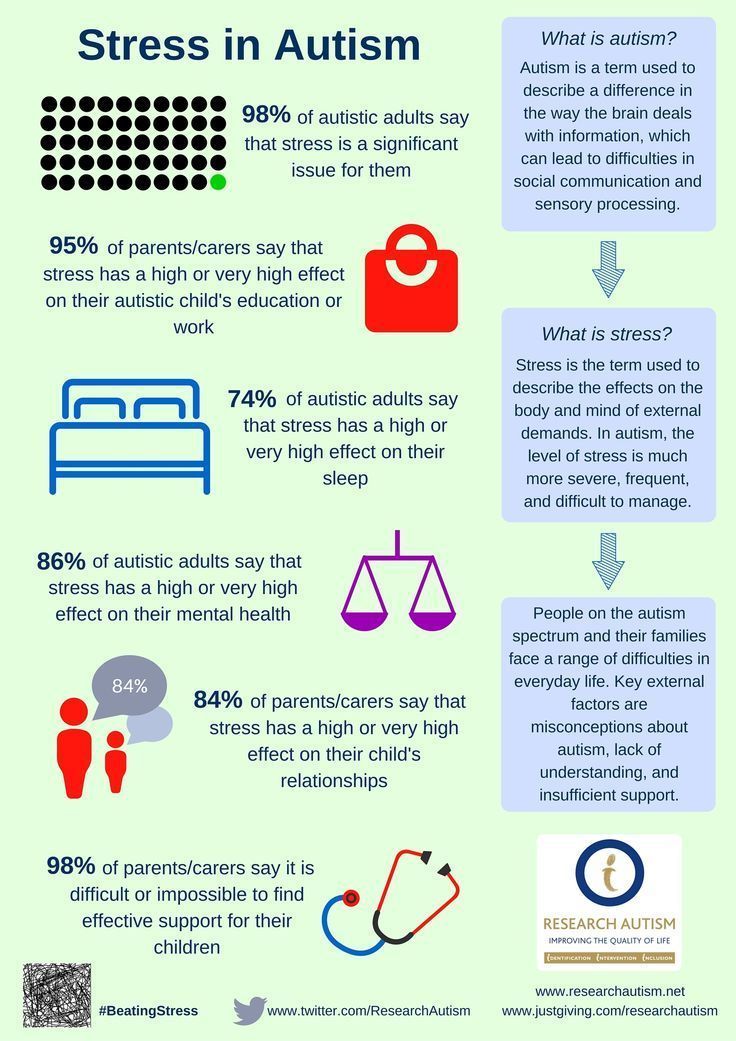

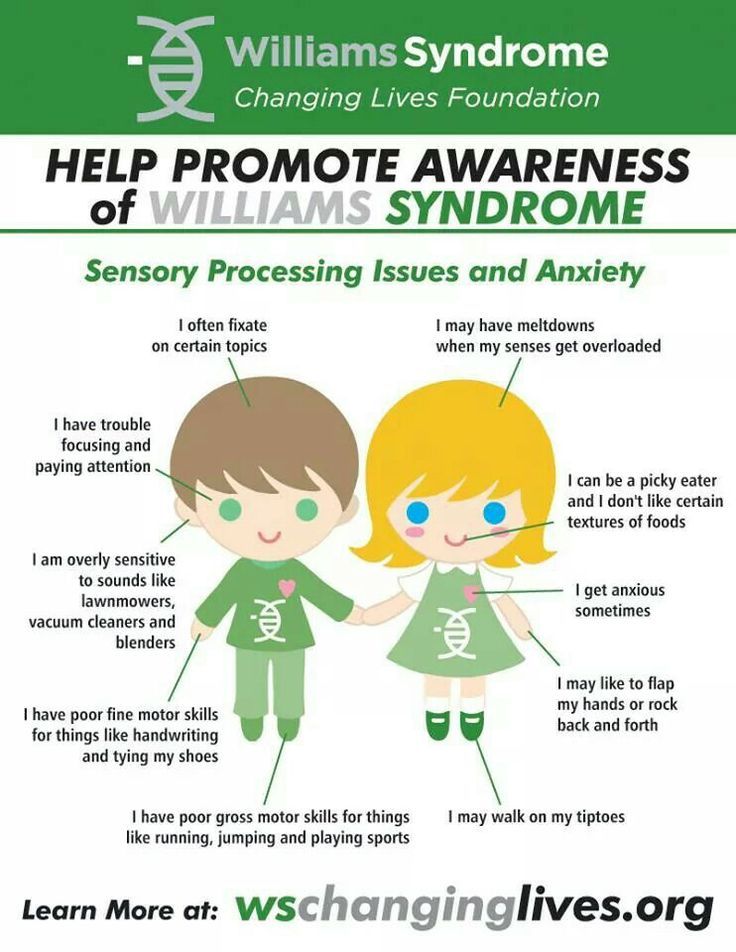

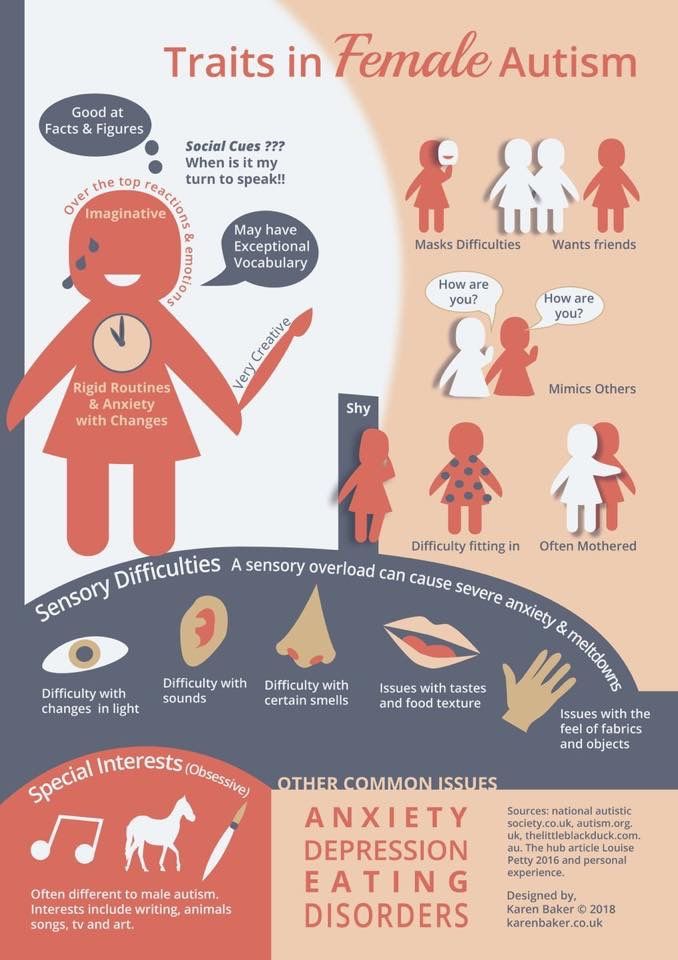

Jack has a sensory processing disorder (SPD). This is the name of the state when people perceive too keenly what they feel, see and hear, or their sensitivity is too low. Some people with SPD find it difficult to integrate information from different senses. NOS is not an official diagnosis. It was not included in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). However, the concept is widely used by clinicians, and some studies suggest that 5-15% of school-age children have such disorders. Children with SPD have much in common with children with autism, 90% of whom have some kind of sensory difficulty.

Jack doesn't have autism, but Ari Young, who lives in North Carolina, has SPD and autism. Thanks to his heightened senses, Ahri also has impressive abilities. His visual memory allows him to quote Wikipedia articles entirely from memory, however, if it is not an article on a historical or scientific topic of interest to him, he can only reproduce the information in the order in which he learned it. Ari's mom, Heather McDaniel, says his sensory abilities and autism are inextricably linked. With his many quirks, she doesn't know "when it's because of autism, when it's something sensory, and when it's a combination of both." nine0003

Ari's mom, Heather McDaniel, says his sensory abilities and autism are inextricably linked. With his many quirks, she doesn't know "when it's because of autism, when it's something sensory, and when it's a combination of both." nine0003

Like Jack, Ari had trouble sleeping as a baby: he could only fall asleep when he was cradled to a recording of birds chirping, and his sleepy parents had to play a recording every 15 minutes throughout the night. The speech therapist suggested that Ari had SPD when he was two years old. He was diagnosed with autism later, at the age of two and a half years.

Even now, at age 9, Ari hums to herself when it's too quiet or too noisy. He is in the third grade of a comprehensive school, but his sensitivity makes it hard to study. A few months ago, it was unexpectedly announced that the class would be sent home early, and the delighted hum of the children caused Ari to sob and run out of the classroom. nine0003

Sensory problems can not only interfere with a child's ability to learn at school and communicate with other children, they wreak havoc in the life of the whole family. “These are very difficult issues in a child’s life, whether or not they have another diagnosis,” says Grace Baranet, a professor of occupational therapy at the University of North Carolina. And it is very difficult for families to find help.

“These are very difficult issues in a child’s life, whether or not they have another diagnosis,” says Grace Baranet, a professor of occupational therapy at the University of North Carolina. And it is very difficult for families to find help.

However, there is a hidden opportunity in SPD: studying people with sensory problems but without autism can help these children and identify the link between sensory problems and underlying social and communication difficulties in autism. It is easy to imagine that a small child who has difficulty recognizing sounds and visual stimuli will miss his dad's attempts to play peek-a-boo with him and lose the opportunity to communicate at a critical period in his life. On the other hand, a child who perceives sounds and lights as too intense will react negatively to the mother's attempts to attract his attention and will not learn any nuances of the social world. nine0003

Over the past few years, more accurate and objective ways to measure sensory responses and behavior, coupled with brain-scanning techniques to determine how the brain processes sensory information, have shown what goes wrong in the process of perception. It is hoped that someday this data will help get this process back on track.

It is hoped that someday this data will help get this process back on track.

Forgotten history

Sensory differences were mentioned in the first descriptions of autism, but in subsequent years they began to be ignored. In his article 19At 43 years old, Leo Kanner first introduced the concept of autism, and the very first description in it mentions a boy with an outstanding talent for singing, a remarkable memory for faces, and a keen dislike for many typical childhood pastimes, be it riding a tricycle or children's slides. Kanner and other researchers noted that many children with autism overreacted to loud noises or seemed immune to pain.

However, in the early decades, research into these aspects of autism was largely descriptive and speculative. Few researchers have collected empirical evidence about how children with this disorder perceive the world. K 19In the 1980s, interest in this area faded.

Meanwhile, outside the context of autism, an occupational therapist and neurologist named A. Jean Ayres has developed the theory that the processing and integration of basic sensory information underlies many daily activities. “It’s hard to imagine now, but then people didn’t realize that if a child has difficulty buttoning up a coat or doing some schoolwork, then this could be due to brain function,” says Roseanne Schaaf, professor of occupational therapy and brain science at Thomas University Jefferson in Philadelphia, USA. nine0003

Jean Ayres has developed the theory that the processing and integration of basic sensory information underlies many daily activities. “It’s hard to imagine now, but then people didn’t realize that if a child has difficulty buttoning up a coat or doing some schoolwork, then this could be due to brain function,” says Roseanne Schaaf, professor of occupational therapy and brain science at Thomas University Jefferson in Philadelphia, USA. nine0003

In the early 1970s, Ayres first described "sensory integration dysfunction" as the cause of difficulty with daily tasks. As scientists learned more about these brain mechanisms, the word "integration" gave way to "processing," and such problems began to be called sensory processing disorder. Ayres developed a test to diagnose these problems, for example, she asked a person to determine, with their eyes closed, which finger was being touched. She also created Sensory Integration Therapy, which includes exercises that engage multiple senses at once, such as searching for objects in the sand or a bean box, or swinging on a swing and hitting a ball at the same time. nine0003

nine0003

Ayres' work has had a huge impact on occupational therapists, medical professionals who help people cope with everyday life skills. Occupational therapists these days are pre-arranged to explain a child's problems, such as handwriting or brushing teeth, as sensory difficulties. And many occupational therapists still use Ayres therapy or similar techniques to help with these problems.

In the early 2000s, autism researchers began to rediscover sensory information processing with new brain-scanning and psychophysics tools: accurately measuring the brain's electrical responses in response to stimuli. A growing number of experts are recognizing that sensory difficulties play a large role in problems in autism. To date, their acceptance is so widespread that this aspect of autism has been included in the latest edition of the diagnostic criteria. nine0003

However, most child psychiatrists do not consider SPD as a separate diagnosis. The symptoms are too varied, they say, and there are no criteria to separate SPD from other conditions such as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or anxiety disorders. “We know that sensory issues are important for many children with a variety of diagnoses,” says Carissa Cascio, professor of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, USA. According to her, the presence of sensory problems without any other diagnosis is very rare. nine0003

“We know that sensory issues are important for many children with a variety of diagnoses,” says Carissa Cascio, professor of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, USA. According to her, the presence of sensory problems without any other diagnosis is very rare. nine0003

However, some parents say that this is at odds with their experience and that their children's problems are primarily perceptual problems. Linda, mother of a child with NOS, recalls that her daughter has always been obsessed with the clothes she wears. But in the first grade, small quirks turned into a real horror of the school - she was afraid to go to the noisy assembly hall and refused to go into the common toilet, where at any moment they could flush the water loudly. (Linda asked that her last name not be used to protect her daughter's personal information.) The pediatrician did an anxiety test, suspecting an anxiety disorder, but the diagnosis didn't quite fit. “She is not afraid of bears or death,” Linda told the psychiatrist. “Socks and hats scare her.” nine0003

“Socks and hats scare her.” nine0003

What's more, a 2012 study of twins found that more than half of children with sensory hypersensitivity do not have anxiety disorders, depression, or ADHD (autism was not included in this study).

In the meantime, the million dollar question remains: How are children with autism and perceptual problems different from children with only perceptual problems? Why does Ari have a recognized disorder (autism) that includes noise overload while Jack has similar problems but no diagnosis? Careful observation of the difference between such children may help in finding the answer. “This is a very useful approach because it allows you to identify by comparison what is specific to autism and what is related to sensory differences in a broad sense,” says Cascio. nine0003

How does it feel

Controversy about SPD created difficulties in such studies. "It's very hard to get funding for something that doesn't exist," says Lucy Miller, an occupational therapist and founder of the NSE Foundation, a nonprofit research and community organization. And if you do not study people with SPD, then it is also impossible to prove that this condition should be considered as a separate diagnosis. "These kids are not being sent to research because they don't have the disorder," according to the diagnostic guidelines, says Elisa Marco, director of the Sensory Neurodevelopment and Autism Program at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s kind of a vicious circle,” she notes. Her research group has now launched a crowdfunding campaign to support NSE research. nine0003

And if you do not study people with SPD, then it is also impossible to prove that this condition should be considered as a separate diagnosis. "These kids are not being sent to research because they don't have the disorder," according to the diagnostic guidelines, says Elisa Marco, director of the Sensory Neurodevelopment and Autism Program at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s kind of a vicious circle,” she notes. Her research group has now launched a crowdfunding campaign to support NSE research. nine0003

Several scientists have been able to research SPD as a separate condition, and their data support that it should be a separate diagnosis. There are children who do not meet the criteria for any of the existing diagnoses, but at the same time they have atypical functioning of sensory systems. The authors of one study used electrodes placed on the skin to show that children with this informal diagnosis are more responsive to everyday stimuli, such as the sound of a siren or the touch of a feather on their face, than children in a control group or children with ADHD. Another study showed that the parasympathetic nervous system, which slows down heartbeat and breathing, is less active in people with sensory perception problems than in controls. nine0003

Another study showed that the parasympathetic nervous system, which slows down heartbeat and breathing, is less active in people with sensory perception problems than in controls. nine0003

The most compelling evidence that SPD has separate neurological causes comes from a 2013 study that showed that in boys with SPD, areas of the brain associated with sensory perception have atypical white matter. “They have real, measurable differences in brain connectivity,” says Marco, who worked on the study.

A follow-up study published earlier this year confirms this finding: the brain connections in girls with SPD are similarly altered, and the more difficult the child's perception of sounds, the greater the difference in white matter. nine0003

These studies also show interesting parallels between children with autism and children with sensory difficulties who are not formally diagnosed. For example, children with autism have decreased activity of the parasympathetic system, as do children with SPD. And children with autism, like children with SPD, have abnormalities in white matter, which is involved in sensory perception.

And children with autism, like children with SPD, have abnormalities in white matter, which is involved in sensory perception.

"It's possible that the two groups start out with the same conditions, but some protective factor keeps children with sensory differences from becoming children with autism," says Cascio. However, this is only a hypothesis at the moment. nine0003

There are also differences between sensory problems in autism, SPD and other conditions, but these are only now beginning to be identified. Children with autism have impaired brain connections that are responsible for social interaction and emotions, but in children with SPD alone, these connections are in order. Children with SPD are more likely to have touch problems than children with autism. At the same time, children with autism are more likely to have difficulty processing auditory information. This may partly explain language and communication problems in autism. nine0003

Hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity may also play a role in the final diagnosis of a child. Reduced responses to new visual, auditory, or tactile information are unique to autism, while a more sensitive sensory system is common to both autism and many other disorders, including ADHD and anxiety disorders. During infancy, children with autism also have more pronounced sensory anomalies than children with mental retardation. nine0003

Reduced responses to new visual, auditory, or tactile information are unique to autism, while a more sensitive sensory system is common to both autism and many other disorders, including ADHD and anxiety disorders. During infancy, children with autism also have more pronounced sensory anomalies than children with mental retardation. nine0003

The idea that sensory issues may underlie autism symptoms makes sense, but has yet to be tested, says Sophie Molholm, professor of pediatrics and brain science at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. "I wouldn't say sensory processing disorders are the cause," she says. “We don't know. We just know that these symptoms are common in these disorders.”

In addition, the relationship between perceptual problems and autism may vary from child to child. “I think this is part of the autism puzzle,” Marco says. - Can children not perceive social information because they are so sensitive that they completely switch off? Or do they really lack social interest? nine0003

Sense and Sensibility

These questions are important because children who are so enmeshed in the world around them that they withdraw from it need help, whether or not they have autism.

Many of the day-to-day difficulties of people with autism are related to problematic perceptions, such as hypersensitivity to sounds or aversion to certain foods. These issues can have a huge impact on the entire family, but they may not be noticed or dealt with by professionals. nine0003

Some parents of children with autism are big fans of sensory integration and similar therapies. They say that such methods help children to be calmer and prevent behaviors that interfere with daily life. Jennifer, mother of a teenage boy with autism and fragile X syndrome, a common cause of autism, says the occupational therapy her son has been receiving since he was three years old has had a huge positive impact. He had not yet spoken at the time, but through therapy she was able to understand that he perceives the world differently and that what calms other people makes him angry. “We figured out why he loves rubbing his hands or getting his shoulders squeezed so much,” says Jennifer. (To protect information about her son, she asked not to give her last name). She understood why her son demanded pajamas, which were too small for him, and wore only one pair of shoes. “Everything made sense to us,” she says, and since then it has been easier for her to respond to her son’s needs. nine0003

She understood why her son demanded pajamas, which were too small for him, and wore only one pair of shoes. “Everything made sense to us,” she says, and since then it has been easier for her to respond to her son’s needs. nine0003

Until a few years ago, there was virtually no scientific evidence to support sensory integration therapy for children with autism. And some of these sensation-focused practices, such as working with plasticine, hanging upside down, or massaging special brushes on a child’s skin, could seem unscientific, if not simply ridiculous. Research into the approach was also made difficult by the fact that practitioners often made prescribing on a whim. Specialists "developed very individual treatment plans, which also made it difficult to conduct thorough scientific research," says Cascio. "It's very difficult to define what counts as a desirable outcome, how to measure it, and what exactly says improvement." In the past, general therapeutic practices have been developed in the field, but not standardized techniques. nine0003

nine0003

It is difficult for families whose children do not have an official diagnosis to receive any help at all. “Many people suffer from these problems, but they can't get services, school adjustments, or early intervention because they don't have a diagnosis,” says Baranek.

Lori Craven homeschooled her son Jack because she found it too difficult to convince the public school system to accommodate him. Jack doesn't have hearing loss, so he wasn't relied on technology to amplify his teacher's voice to help him focus. He is not visually impaired, so the school was against him working on worksheets with larger, simplified text, they didn't even let Laurie prepare such worksheets. “I just realized that I was wasting so much time fighting the school — I was ready to do everything for them, but they couldn’t even do that,” she says. nine0003

Experienced parents of children with SPD often seek an additional diagnosis, such as anxiety or ADHD, or do not argue when any other diagnosis is offered to the child. Linda says the fact that her daughter was diagnosed with anxiety helped the family get her daughter an individualized education program. Diagnosis is the language “the school will best understand,” she says.

Linda says the fact that her daughter was diagnosed with anxiety helped the family get her daughter an individualized education program. Diagnosis is the language “the school will best understand,” she says.

Perhaps in the future such tricks will no longer be needed, because now for the first time scientists have begun to study what methods are still effective for sensory problems. Appropriate therapy is expected to be effective for children with autism, anxiety disorders, ADHD, or no diagnosis at all, as long as the problem is the same, such as being sensitive to touch. “We're trying to highlight what everyone has in common,” says Baranek. “And to determine which methods really help despite different diagnoses.” nine0003

This means that the treatment will be tailored to the child, not the diagnosis. “I think occupational therapists already know how to do this,” says Alison Lane, professor of occupational therapy at the University of Newcastle in Australia. “But we don’t have a systematic approach that would allow us to say that if a child has such behavioral and sensory features, then it is best to apply this approach. ”

”

Lane and her colleagues are now working on identifying sensory subtypes in autism to begin to more systematically tailor therapy to specific symptoms. She plans to pilot this approach to therapy next year. nine0003

A well-defined procedure for selecting sensory therapy would also facilitate research in this area, says Schaaf, an occupational therapist and brain researcher in Philadelphia who is leading the development of this approach. She explores whether sensory therapy or more standard behavioral therapy can help people with autism better integrate auditory and visual information.

An earlier small pilot study showed that sensory therapy in children with autism improves not only their perception but also their social skills. “It came as a surprise,” says Schaaf. “We didn’t have such a hypothesis.” In a follow-up study, she and her colleagues teamed up with Molholm's team to measure children's sensory integration abilities using electroencephalography, as well as monitor their progress in daily life. This study will run for five years and will involve 200 children and is set to begin in February of this year. nine0003

This study will run for five years and will involve 200 children and is set to begin in February of this year. nine0003

Scientists are also using neurobiological data to develop treatments for SPD. Marco is collaborating with the SPD Foundation on a pilot study in which the brains of children with SPD are scanned before and after occupational therapy to determine if the intervention can improve brain connections.

Meanwhile, Ari Young has come up with his own version of therapy for his overly sensitive brain, in addition to the therapy he receives for autism. At school, he often wears earmuffs to reduce the stress of loud noises, but he has noticed that most of the other kids don't wear them. “I felt like the headphones kind of made me stand out, because they made other people think I was ignoring them,” he says. It is also difficult for him to listen to the teacher with headphones. nine0003

So Ari does some sort of informal sensory therapy, forcing herself to take her headphones off from time to time during school assemblies or holidays. “Sometimes there are quiet moments in a loud concert when… I decide to listen for a while without headphones,” he says. “And when it gets loud again, I put them back on as soon as possible.”

“Sometimes there are quiet moments in a loud concert when… I decide to listen for a while without headphones,” he says. “And when it gets loud again, I put them back on as soon as possible.”

See also:

Understanding sensory perception in autism

How to prevent stress from sensory overload

How sensory integration can change the brain in autism

What is sensory desensitization in children with autism

How to help a child with autism who can't handle loud noises

How to help a child with autism cope with overstimulation

Notes from an Autist. Living with an auditory processing disorder

Can a behavioral analyst help with sensory problems

We hope you find the information on our website useful or interesting. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button. nine0003

Techniques and treatment, Research, Sensory and motor skills, Comorbidities

Acuity.

Sensory integration disorders in children in Novosibirsk

Sensory integration disorders in children in Novosibirsk Some parents are concerned about the child's behavior: difficulties in communicating and playing with peers, hyperactivity, inattention, distraction, frequent mood swings, excitability or lethargy, poor sleep. The child cannot independently do homework and organize his free time. It often happens that parents mistake such behavior for a character trait or laziness, but in many cases it is a sign of a sensory integration disorder. How to help your child and change the situation for the better, said Lyudmila Vyacheslavovna Efimova, a neurologist. nine0140

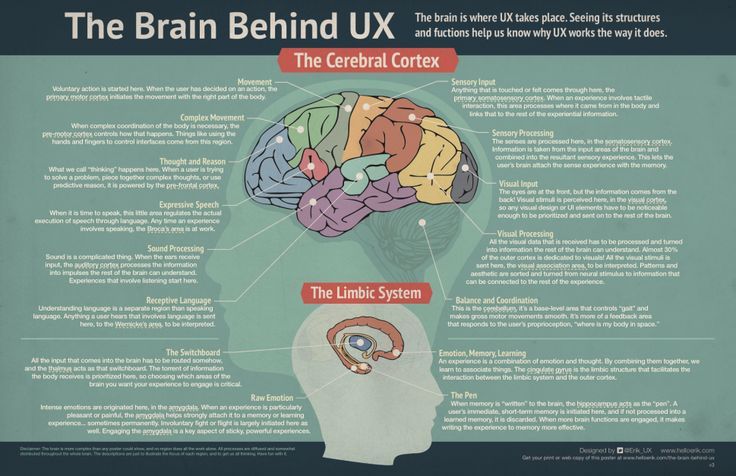

A child is born without any experience with the environment. From the first seconds of life, various sensations begin to enter the brain through the senses. A series of sensations allows us to receive information about the state of the body and the world around us, accumulating sensory experience that a person needs to control the body and thinking.

Sense organs through which information enters the nervous system:

Sense organs, their receptors, pathways and the part of the brain responsible for processing the received signals, together form a sensory system. The best known sensory systems are sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell. They help us feel the physical properties of the world around us: temperature, taste, sound or pressure. nine0003

- sight, hearing, smell, touch;

- tactile - received through skin receptors from touch, pressure, temperature, pain;

- vestibular - received from the inner ear about the state of balance, gravitational changes, movement and position of the body in space;

- proprioceptive - derived from muscles and joints about body position, weight, pressure, stretch.

The sensory system allows us to receive information from the senses, and sensory integration to process it and further use it as an experience of interaction with the outside world. nine0003

nine0003

The child's sensory system is quite fragile, so adverse factors can lead to a gradual onset of disturbances. They can be seen by the following signs:

- difficulty concentrating, “hears” mother only after the 3rd time;

- the child is restless and restless, impulsive, his mood often changes;

- quickly get bored with activities, toys;

- ignores rules of conduct;

- forgets and often loses things; nine0152

- sleeps poorly, often wakes up at night;

- is afraid of water.

In infants

There are no symptoms of sensory integration disorders at this age yet, but some prerequisites for their appearance can be created if the baby's mobility is limited. For example, if a mother always carries a child in her arms, not allowing him to move enough, then the baby lacks the experience gained from independent movements. To prevent this from happening, parents need to create conditions for the baby that are optimal for motor and speech development. To do this, it is important to talk with the baby, let him crawl, explore and touch objects made of different materials and different sizes, show toys of different colors. nine0003

To do this, it is important to talk with the baby, let him crawl, explore and touch objects made of different materials and different sizes, show toys of different colors. nine0003

Preschoolers

Inability to play is a very common symptom of sensory integration disorder during preschool years. The child cannot build a house out of cubes, hold a toy, or fold a simple mosaic. The child does not feel his body and does not know how to control it, his motor coordination suffers, he loses his balance, stumbles all the time, drops objects more often than his peers. In this case, the child is shown classes with a physical therapist.

Junior students

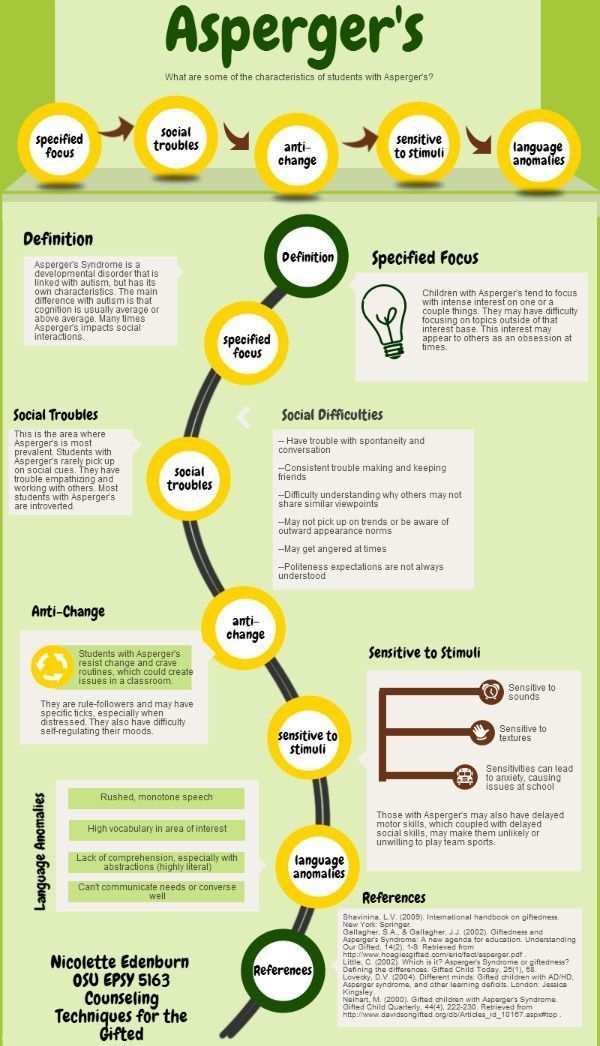

At school age, children with sensory integration disorders have learning problems. This arises either from the difficulty of mastering the curriculum, or from violations of the behavior associated with schooling, even if learning abilities are not reduced.

The child tries to concentrate, but it is difficult for him, all his strength is spent on it, which makes him very tired. Against the background of fatigue, the child begins to be distracted by extraneous sounds, actions, his brain is overexcited and the child may begin to “jump around the class” not because he wants to do it, but because his brain is getting out of control. nine0003

Against the background of fatigue, the child begins to be distracted by extraneous sounds, actions, his brain is overexcited and the child may begin to “jump around the class” not because he wants to do it, but because his brain is getting out of control. nine0003

The child cannot explain his problems or understand and evaluate what is happening, because the brain processes are unconscious and not subject to control. Adults often only exacerbate the problems of the child, forcing him to perform overwhelming tasks. But it is important to understand that neither rewards nor punishments can affect the situation, so it is worth contacting a neurologist with such behavior.

Adolescents

One of the most common complaints of parents of adolescents with sensory disabilities is incoherence. It is difficult for the brain to organize sensations and therefore everything else. A teenager is unable to concentrate on tasks such as cleaning a room or writing an essay, it is difficult for him to plan a series of tasks, he does not know where to start, or how long each action will take.