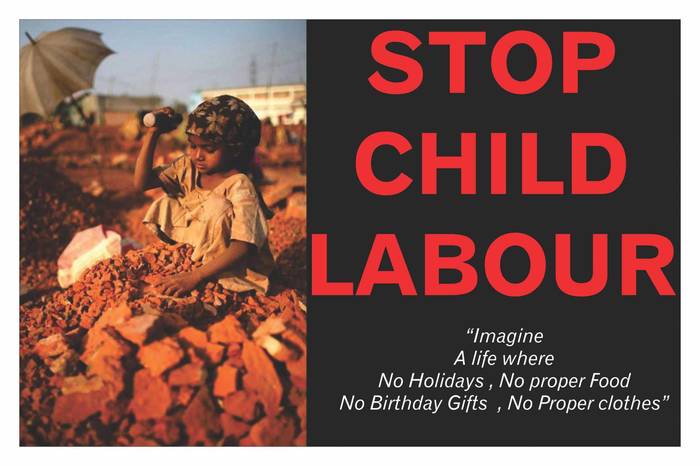

How did child labour start

Child Labor in U.S. History

Breaker Boys

Hughestown Borough Pa. Coal Co.

Pittston, Pa.

Photo: Lewis Hine

Forms of child labor, including indentured servitude and child slavery, have existed throughout American history. As industrialization moved workers from farms and home workshops into urban areas and factory work, children were often preferred, because factory owners viewed them as more manageable, cheaper, and less likely to strike. Growing opposition to child labor in the North caused many factories to move to the South. By 1900, states varied considerably in whether they had child labor standards and in their content and degree of enforcement. By then, American children worked in large numbers in mines, glass factories, textiles, agriculture, canneries, home industries, and as newsboys, messengers, bootblacks, and peddlers.

Spinning Room

Cornell Mill

Fall River, Mass.

Photo: Lewis Hine

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the numbers of child laborers in the U. S. peaked. Child labor began to decline as the labor and reform movements grew and labor standards in general began improving, increasing the political power of working people and other social reformers to demand legislation regulating child labor. Union organizing and child labor reform were often intertwined, and common initiatives were conducted by organizations led by working women and middle class consumers, such as state Consumers’ Leagues and Working Women’s Societies. These organizations generated the National Consumers’ League in 1899 and the National Child Labor Committee in 1904, which shared goals of challenging child labor, including through anti-sweatshop campaigns and labeling programs. The National Child Labor Committee’s work to end child labor was combined with efforts to provide free, compulsory education for all children, and culminated in the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which set federal standards for child labor.

1832 New England unions condemn child labor

The New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen resolve that “Children should not be allowed to labor in the factories from morning till night, without any time for healthy recreation and mental culture,” for it “endangers their . . . well-being and health”

. . well-being and health”

Women's Trade Union League of New York

1836 Early trade unions propose state minimum age laws

Union members at the National Trades’ Union Convention make the first formal, public proposal recommending that states establish minimum ages for factory work

1836 First state child labor law

Massachusetts requires children under 15 working in factories to attend school at least 3 months/year

1842 States begin limiting children’s work days

Massachusetts limits children’s work days to 10 hours; other states soon pass similar laws—but most of these laws are not consistently enforced

1876 Labor movement urges minimum age law

Working Men’s Party proposes banning the employment of children under the age of 14

1881 Newly formed AFL supports state minimum age laws

The first national convention of the American Federation of Labor passes a resolution calling on states to ban children under 14 from all gainful employment

1883 New York unions win state reform

Led by Samuel Gompers, the New York labor movement successfully sponsors legislation prohibiting cigar making in tenements, where thousands of young children work in the trade

1892 Democrats adopt union recommendations

Democratic Party adopts platform plank based on union recommendations to ban factory employment for children under 15

National Child Labor Committee

1904 National Child Labor Committee forms

Aggressive national campaign for federal child labor law reform begins

1916 New federal law sanctions state violators

First federal child labor law prohibits movement of goods across state lines if minimum age laws are violated (law in effect only until 1918, when it’s declared unconstitutional, then revised, passed, and declared unconstitutional again)

1924 First attempt to gain federal regulation fails

Congress passes a constitutional amendment giving the federal government authority to regulate child labor, but too few states ratify it and it never takes effect

1936 Federal purchasing law passes

Walsh-Healey Act states U. S. government will not purchase goods made by underage children

S. government will not purchase goods made by underage children

1937 Second attempt to gain federal regulation fails

Second attempt to ratify constitutional amendment giving federal government authority to regulate child labor falls just short of getting necessary votes

1937 New federal law sanctions growers

Sugar Act makes sugar beet growers ineligible for benefit payments if they violate state minimum age and hours of work standards

1938 Federal regulation of child labor achieved in Fair Labor Standards Act

For the first time, minimum ages of employment and hours of work for children are regulated by federal law

Educational materials containing more information on Child Labor in U.S. History and Causes of Child Labor, including Workshop Materials—Core Workshop on Child Labor and K-12 Teachers’ Materials, are available through this web site. These materials include Power Point presentations, instructors’ manuals, activities, and handouts. You may adapt these materials to your group’s needs.

Child labor | Definition, History, Laws, & Facts

Lewis W. Hine: photograph of an overseer and child workers in the Yazoo City Yarn Mills

See all media

- Key People:

- Grace Abbott Florence Kelley Madeline McDowell Breckinridge Helen Marot Lewis Hine

- Related Topics:

- labour childhood

See all related content →

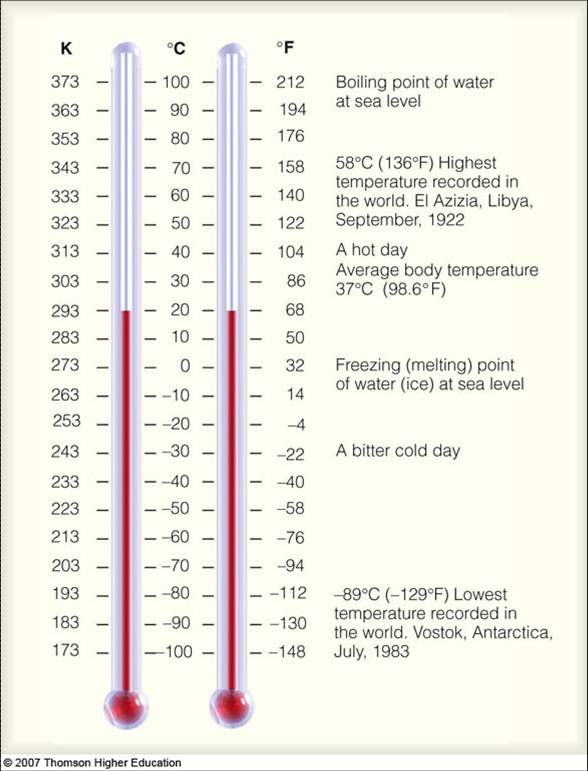

child labour, employment of children of less than a legally specified age. In Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, children under age 15 rarely work except in commercial agriculture, because of the effective enforcement of laws passed in the first half of the 20th century. In the United States, for example, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 set the minimum age at 14 for employment outside of school hours in nonmanufacturing jobs, at 16 for employment during school hours in interstate commerce, and at 18 for occupations deemed hazardous.

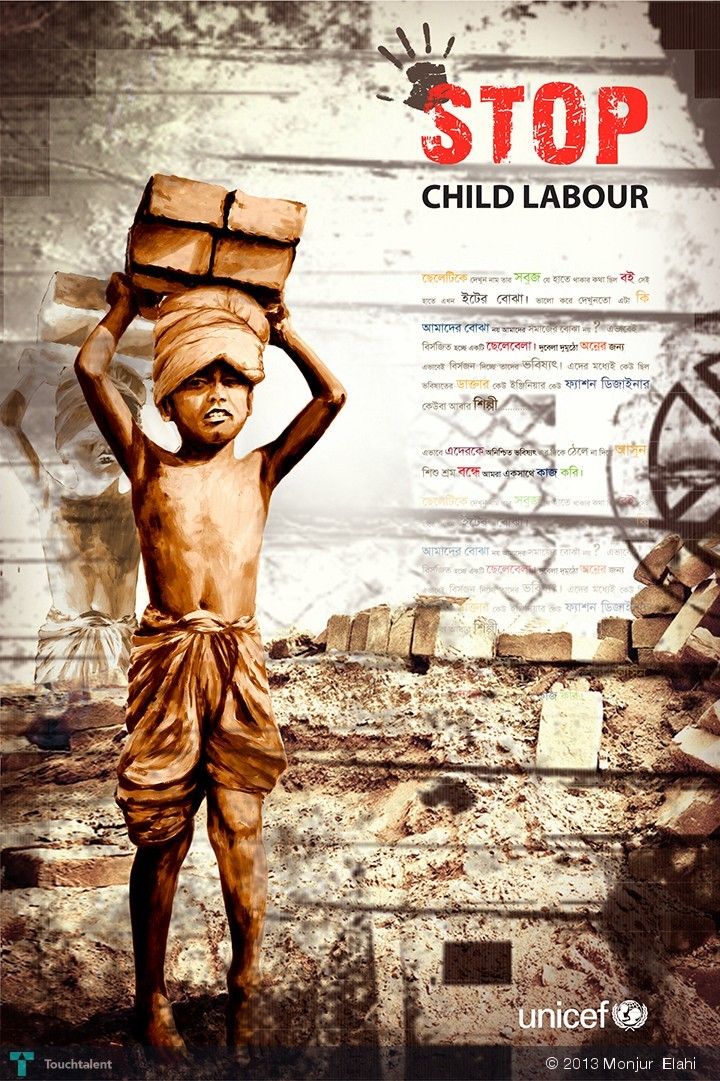

Child labour is far more prevalent in developing countries, where millions of children—some as young as seven—still toil in quarries, mines, factories, fields, and service enterprises. They make up more than 10 percent of the labour force in some countries in the Middle East and from 2 to 10 percent in much of Latin America and some parts of Asia. Few, if any, laws govern their employment or the conditions under which work is performed. Restrictive legislation is rendered impractical by family poverty and lack of schools.

Discover the revolution that changed child labour in the United States

See all videos for this articleThe movement to regulate child labour began in Great Britain at the close of the 18th century, when the rapid development of large-scale manufacturing made possible the exploitation of young children in mining and industrial work. The first law, in 1802, which was aimed at controlling the apprenticeship of pauper children to cotton-mill owners, was ineffective because it did not provide for enforcement. In 1833 the Factory Act did provide a system of factory inspection.

In 1833 the Factory Act did provide a system of factory inspection.

Organized international efforts to regulate child labour began with the first International Labour Conference in Berlin in 1890. Although agreement on standards was not reached at that time, similar conferences and other international moves followed. In 1900 the International Association for Labour Legislation was established at Basel, Switzerland, to promote child labour provisions as part of other international labour legislation. A report published by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) of the United Nations in 1960 on law and practice among more than 70 member nations showed serious failures to protect young workers in nonindustrial jobs, including agriculture and handicrafts. One of the ILO’s current goals is to identify and resolve the “worst forms” of child labour; these are defined as any form of labour that negatively impacts a child’s normal development. In 1992 the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) was created as a new department of the ILO. Through programs it operates around the world, IPEC seeks the removal of children from hazardous working conditions and the ultimate elimination of child labour.

Through programs it operates around the world, IPEC seeks the removal of children from hazardous working conditions and the ultimate elimination of child labour.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaThis article was most recently revised and updated by Adam Augustyn.

Struggle for happy slavery - Money - Kommersant

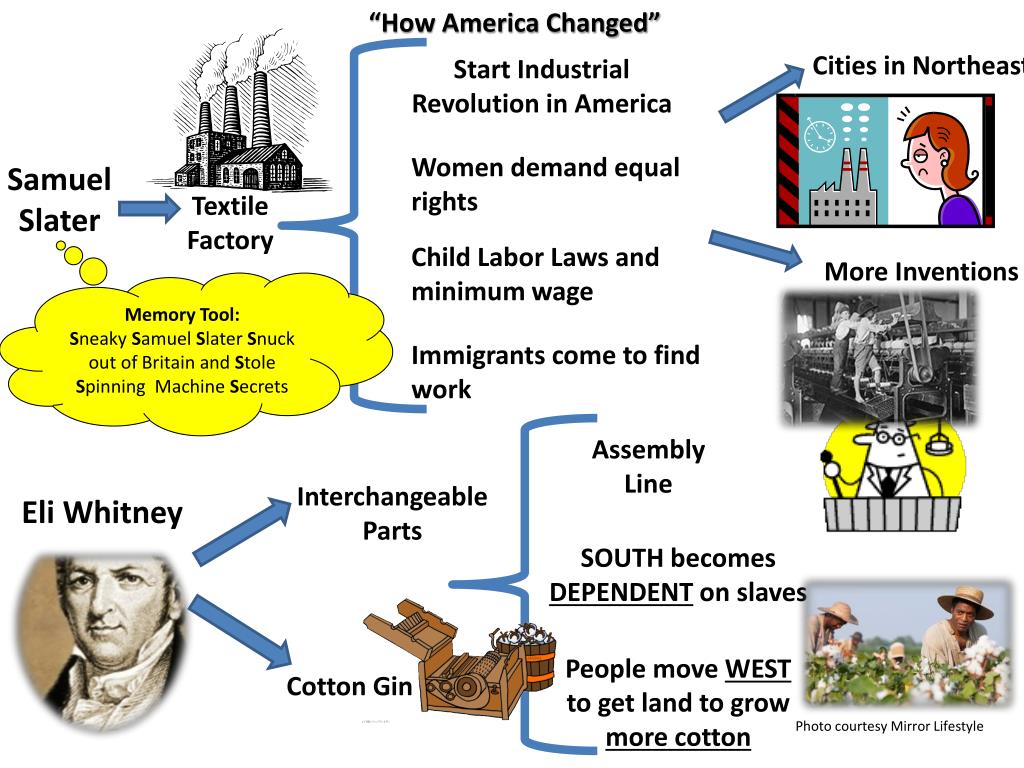

90 years ago in the United States, the Hammer v. Dagenhart trial ended, as a result of which the country's first federal law prohibiting the use of child labor in enterprises was repealed. The most striking thing was that the initiator of its abolition was not a bourgeois exploiter, but a simple inhabitant of one-story America, who wanted his sons to work at the factory. The struggle against the exploitation of children has been going on with varying success for about 200 years, but so far it has been possible to eradicate it only in those countries where the industrial revolution has fully completed.

Labor reserves

At one time, stories about difficult working childhood were an integral part of the biography of Soviet figures of various levels. If the future responsible worker did not herd geese as a child or did not stand at the barre until late at night, it looked suspiciously bourgeois, so that the corresponding episodes were invented, even if they were not there. All the horrors of the exploitation of minors were unconditionally attributed to the inhuman cruelty of the tsarist regime and the bourgeois system. Soviet children, on the other hand, could study at school, and not work from morning to night, only thanks to the wisdom of the Soviet leadership. Meanwhile, the history of child labor in Europe and North America suggests that the most brutal exploitation of children occurred during the years of early industrialization. When the industry developed to a certain level, the use of child labor under the pressure of society came to naught. So the point here is in the general laws of development, and not in the innate defects of capitalism.

If the future responsible worker did not herd geese as a child or did not stand at the barre until late at night, it looked suspiciously bourgeois, so that the corresponding episodes were invented, even if they were not there. All the horrors of the exploitation of minors were unconditionally attributed to the inhuman cruelty of the tsarist regime and the bourgeois system. Soviet children, on the other hand, could study at school, and not work from morning to night, only thanks to the wisdom of the Soviet leadership. Meanwhile, the history of child labor in Europe and North America suggests that the most brutal exploitation of children occurred during the years of early industrialization. When the industry developed to a certain level, the use of child labor under the pressure of society came to naught. So the point here is in the general laws of development, and not in the innate defects of capitalism.

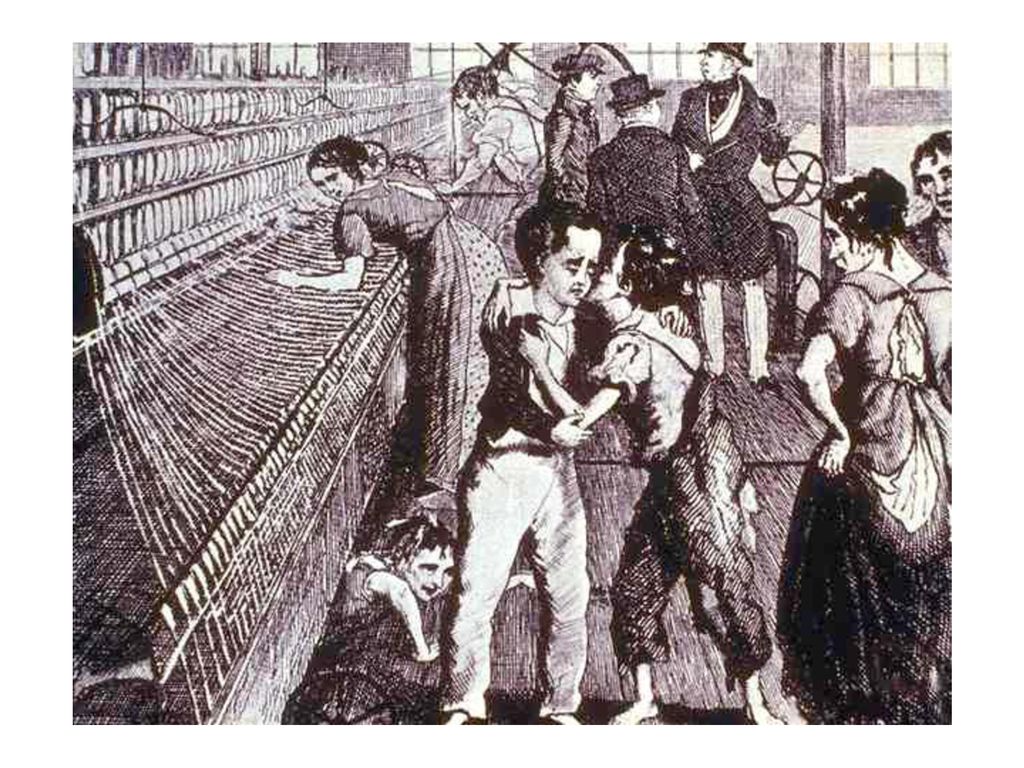

Children have been forced to work since time immemorial, but this work was usually quite feasible and even beneficial for health and general development. Picking up mushrooms and berries, grazing cattle, fetching water and other joys of rural life were, in fact, not so burdensome. But the beginning of the industrial revolution turned all European ideas about barefoot childhood upside down. This revolution began in England in the second half of the 18th century, and not everyone liked what it brought with it. English workers often grumbled against low wages, broke expensive factory machines in protest, or even crushed the sides of the manager. Employers dreamed of more obedient, more defenseless and, if possible, physically weak workers. The children were the best fit, and British entrepreneurs soon moved on to the mass recruitment of children between the ages of eight and fourteen.

Picking up mushrooms and berries, grazing cattle, fetching water and other joys of rural life were, in fact, not so burdensome. But the beginning of the industrial revolution turned all European ideas about barefoot childhood upside down. This revolution began in England in the second half of the 18th century, and not everyone liked what it brought with it. English workers often grumbled against low wages, broke expensive factory machines in protest, or even crushed the sides of the manager. Employers dreamed of more obedient, more defenseless and, if possible, physically weak workers. The children were the best fit, and British entrepreneurs soon moved on to the mass recruitment of children between the ages of eight and fourteen.

Children got to the factories in two ways: either they were sent there by their parents, or, if there were no father and mother, shelters or workhouses were arranged with employers. Parents sent their children to the shops, of course, not from a good life, just poor families had nothing to live on. Even the children of more or less prosperous parents were not insured against employment. This happened, for example, with the future great writer Charles Dickens. The writer's father, John Dickens, was a clerk in a state institution and, as a person of an intelligent profession, was considered a gentleman. As befits a middle-class son, Charles went to school and could look forward to further education. But in 1824, John Dickens was unable to pay off his creditors and was thrown into the Marshalsea debtor's prison. To make ends meet, the family, which had eight children, sent Charles to work in a wax factory, where the future writer spent ten hours a day sticking labels on boxes of shoe polish for 6 shillings a week. Soon, however, the father was released from prison and took the boy from the factory, but difficult memories haunted Dickens all his life.

Even the children of more or less prosperous parents were not insured against employment. This happened, for example, with the future great writer Charles Dickens. The writer's father, John Dickens, was a clerk in a state institution and, as a person of an intelligent profession, was considered a gentleman. As befits a middle-class son, Charles went to school and could look forward to further education. But in 1824, John Dickens was unable to pay off his creditors and was thrown into the Marshalsea debtor's prison. To make ends meet, the family, which had eight children, sent Charles to work in a wax factory, where the future writer spent ten hours a day sticking labels on boxes of shoe polish for 6 shillings a week. Soon, however, the father was released from prison and took the boy from the factory, but difficult memories haunted Dickens all his life.

In the case of the orphans, things were much simpler. Entrepreneurs practically bought them from workhouses and signed enslaving contracts with them, in fact turning them into slaves. So did, for example, George Cortold, the owner of a silk mill in Essex and a great liberal. Cortold was a zealous Protestant and a staunch opponent of all tyranny. He, being an Englishman, enthusiastically welcomed the American Revolution and even lived for several years in the USA, and later, having already returned to his homeland, supported the French Revolution in the same way. But all this did not prevent him from becoming a real slave owner. Cortold bought children, mostly girls, from workhouses in London, preferring to take them between the ages of 10 and 13. The businessman paid £5 per child immediately upon purchase, and then paid £5 a year later if the child was still alive. The workhouse undertook to provide the child with "a complete change of ordinary clothes." Having obtained another girl, Kortold entered into a separate contract with her, according to which the orphan was obliged to work in the factory until she was 21 years old, and the wages were 1 shilling 5d per week, while the adult worker received 7 shillings 2d.

So did, for example, George Cortold, the owner of a silk mill in Essex and a great liberal. Cortold was a zealous Protestant and a staunch opponent of all tyranny. He, being an Englishman, enthusiastically welcomed the American Revolution and even lived for several years in the USA, and later, having already returned to his homeland, supported the French Revolution in the same way. But all this did not prevent him from becoming a real slave owner. Cortold bought children, mostly girls, from workhouses in London, preferring to take them between the ages of 10 and 13. The businessman paid £5 per child immediately upon purchase, and then paid £5 a year later if the child was still alive. The workhouse undertook to provide the child with "a complete change of ordinary clothes." Having obtained another girl, Kortold entered into a separate contract with her, according to which the orphan was obliged to work in the factory until she was 21 years old, and the wages were 1 shilling 5d per week, while the adult worker received 7 shillings 2d. The well-established system failed only once. In 1814, several girls ran away from the factory and told about the brutal beatings that the factory clerk arranged. Kortold extinguished the scandal that had begun by firing the perpetrator of the beatings, and put his four daughters to oversee the labor process. It is not known whether the beatings have stopped at the factory, but the conversations there have definitely stopped. Cortold's daughters were as pious as he was, and therefore forced the workers to sing religious hymns during work and categorically forbade them to talk to each other. No one talked more about running away from the factory.

The well-established system failed only once. In 1814, several girls ran away from the factory and told about the brutal beatings that the factory clerk arranged. Kortold extinguished the scandal that had begun by firing the perpetrator of the beatings, and put his four daughters to oversee the labor process. It is not known whether the beatings have stopped at the factory, but the conversations there have definitely stopped. Cortold's daughters were as pious as he was, and therefore forced the workers to sing religious hymns during work and categorically forbade them to talk to each other. No one talked more about running away from the factory.

Happy childhood

Child labor was made possible by machines that even physically weak people could work with. At the same time, the technologies were so imperfect that it was possible to do without high qualification. For example, in cotton mills there were special professions - scavengers and knotters, which were almost entirely reserved for children. In general, only a child could be a scavenger, since the owner of this profession had to be small and agile. The scavengers had to crawl under the spinning looms all day and pick up pieces of cotton that fell on the floor. The newspaper The Lion wrote about one of these juvenile scavengers in 1828: “The first task of Robert Blinkow was to pick up cotton that fell on the floor. It would seem that it could be easier ... But the boy was very frightened by the movement and noise of the mechanisms. he did not like the cotton dust that hung in the air, because of which he quickly began to suffocate. He soon felt ill, and his back hurt. Blinkow tried to sit up, but this, as it turned out, was strictly prohibited in cotton mills. Manager Mr. Smith ordered him to stay on his feet. This work was not only tedious, but also quite dangerous. A juvenile scavenger from Manchester, David Rowland, said in 1832: “The scavenger has to sweep with a brush under the wheels ... I often had to crawl under the wheels, but they are moving all the time, and I could get into the car.

In general, only a child could be a scavenger, since the owner of this profession had to be small and agile. The scavengers had to crawl under the spinning looms all day and pick up pieces of cotton that fell on the floor. The newspaper The Lion wrote about one of these juvenile scavengers in 1828: “The first task of Robert Blinkow was to pick up cotton that fell on the floor. It would seem that it could be easier ... But the boy was very frightened by the movement and noise of the mechanisms. he did not like the cotton dust that hung in the air, because of which he quickly began to suffocate. He soon felt ill, and his back hurt. Blinkow tried to sit up, but this, as it turned out, was strictly prohibited in cotton mills. Manager Mr. Smith ordered him to stay on his feet. This work was not only tedious, but also quite dangerous. A juvenile scavenger from Manchester, David Rowland, said in 1832: “The scavenger has to sweep with a brush under the wheels ... I often had to crawl under the wheels, but they are moving all the time, and I could get into the car. I often had to lie down on my face so that I would not dragged on." Rowland began working as a scavenger at the age of six. The knotters walked around the workshop and sorted out the threads that went along the loom, and, as a contemporary calculated, in a day a child working in this position, moving around the workshop, walked about 24 miles.

I often had to lie down on my face so that I would not dragged on." Rowland began working as a scavenger at the age of six. The knotters walked around the workshop and sorted out the threads that went along the loom, and, as a contemporary calculated, in a day a child working in this position, moving around the workshop, walked about 24 miles.

Not only in the Cortold factory, but everywhere, children were paid significantly less than adults. One boy talked about the pay system that existed in his factory: “Eight-year-olds used to get 3 or 4 pence a day. Now an adult’s salary is divided into eight eighths: at 11 years old you are paid two eighths, at 13 three eighths, at 15 four, and at 20 already as an adult - 15 shillings. At the same time, the manufacturers insisted that the children should be grateful to them, since they provided them with food and clothing. The quality of the food, however, was debatable. A contemporary wrote: "The children were led into a spacious room with long narrow tables and wooden benches. They were ordered to sit at the tables, boys and girls separately. They were brought dinner - milk porridge, which for some reason looked completely blue."

They were ordered to sit at the tables, boys and girls separately. They were brought dinner - milk porridge, which for some reason looked completely blue."

Working conditions were also very difficult, although not more difficult than for adults. First of all, children suffered from a lack of safety equipment, which distinguished almost all enterprises in the first half of the 19th century. In 1832, 53-year-old worker John Ollet said: “As far as I know, accidents happen more often at the beginning of the day than in the evening. I saw one such case with my own eyes. The child worked with wool, that is, prepared wool for the machine, but here his belt got caught because he was half asleep, and dragged him into the car. Well, then we found him: one piece there, the other here. His whole body went through the car, cut him into pieces. "

In spite of all this, of course, the children did not grumble, they did not break cars and did not go on strikes. And yet, the factory administration sometimes applied very cruel measures to them. One young worker, for example, said: "When I was seven years old, I went to the factory of Mr. Marshals in Shrubary. If any boy was sleepy, the clerk would take him by the shoulder and say:" Come here. "And in the corner There was an iron tank with water in the room, he brings the boy to the tank, grabs him by the legs and dips his head into the tank, and then sends him back to work. Perhaps such a seemingly cruel procedure saved more than one young life from a terrible death, because sleepy workers really often died, but sometimes real sadists came across among the factory authorities. In 1849In 1999, the Ashton Chronicle published an interview with underage Sarah Carpenter, who spoke a lot about her managers: "The master carder was called Thomas Birx, but everyone called him Tom the Devil. how he lifted the skirts of adult girls 17 and 18 years old, threw them over his knee and flogged them in front of men and boys. Everyone was afraid of him ... One day he fell ill, and we hoped that he would die.

One young worker, for example, said: "When I was seven years old, I went to the factory of Mr. Marshals in Shrubary. If any boy was sleepy, the clerk would take him by the shoulder and say:" Come here. "And in the corner There was an iron tank with water in the room, he brings the boy to the tank, grabs him by the legs and dips his head into the tank, and then sends him back to work. Perhaps such a seemingly cruel procedure saved more than one young life from a terrible death, because sleepy workers really often died, but sometimes real sadists came across among the factory authorities. In 1849In 1999, the Ashton Chronicle published an interview with underage Sarah Carpenter, who spoke a lot about her managers: "The master carder was called Thomas Birx, but everyone called him Tom the Devil. how he lifted the skirts of adult girls 17 and 18 years old, threw them over his knee and flogged them in front of men and boys. Everyone was afraid of him ... One day he fell ill, and we hoped that he would die. While he was ill, they appointed him instead clerk William Hughes. He came up to me and asked why the machine stopped. I said I didn’t know, because I didn’t stop it. Hughes began to beat me with a cane, and I told him that I would tell all my mothers. Then he called the master. The master began to beat me on the head with a stick, so that I was covered in blood." Managers from that factory killed one woman after all, kicking her "where you can't kick."

While he was ill, they appointed him instead clerk William Hughes. He came up to me and asked why the machine stopped. I said I didn’t know, because I didn’t stop it. Hughes began to beat me with a cane, and I told him that I would tell all my mothers. Then he called the master. The master began to beat me on the head with a stick, so that I was covered in blood." Managers from that factory killed one woman after all, kicking her "where you can't kick."

Principle and the beggars

It cannot be said that the British public was completely uninterested in the conditions of life of working children. On the contrary, their position was regularly debated in Parliament from the early years of the 19th century. Already in 1802, a law was passed that limited the working day of orphans working in cotton spinning factories to 12 hours. Such solicitude was largely due to the fact that the landed aristocracy, who ruled in those years in British politics, was not too worried about the problems of the manufacturers, who were looked upon by many lords in those years as upstarts with dubious origins, who made a fortune in no less dubious ways. On the other hand, the aristocrats were sensitive to issues related to public morality, and the factory atmosphere, as many believed, had a corrupting effect on the youth. One doctor, in particular, wrote: "The combination under one factory roof of many young people of both sexes is an inexhaustible source of moral decay. Exposure to heated air, contacts between members of opposite sexes, observed examples of the manifestation of animal passions - all this contributes to the development of an extremely early sexual desire" . So factories in high society were viewed with great suspicion and, on occasion, were ready to come up with some kind of prohibition for their owners.

On the other hand, the aristocrats were sensitive to issues related to public morality, and the factory atmosphere, as many believed, had a corrupting effect on the youth. One doctor, in particular, wrote: "The combination under one factory roof of many young people of both sexes is an inexhaustible source of moral decay. Exposure to heated air, contacts between members of opposite sexes, observed examples of the manifestation of animal passions - all this contributes to the development of an extremely early sexual desire" . So factories in high society were viewed with great suspicion and, on occasion, were ready to come up with some kind of prohibition for their owners.

In 1818, another public campaign for the defense of morals led to the fact that the issue of child labor was considered in Parliament in detail. Doctors invited to the meetings of the special committee of the House of Lords, who had practice in industrial regions, reported on the state of health of working children. Doctors unanimously claimed that the children in the factories were as healthy as everyone else. For example, Dr. Edward Holm said that factory children are "no less healthy than other children from working families", and Dr. Thomas Turner assured that children working in cotton mills "make a generally good and healthy impression." Such medical unanimity was easily explained, because the called-up doctors conducted regular medical examinations in factories and received money from their owners for this. And yet in 1819In 1999, Parliament passed a law banning the employment of children under the age of 9 in cotton mills and establishing a 12-hour working day for those under 16 years of age.

Doctors unanimously claimed that the children in the factories were as healthy as everyone else. For example, Dr. Edward Holm said that factory children are "no less healthy than other children from working families", and Dr. Thomas Turner assured that children working in cotton mills "make a generally good and healthy impression." Such medical unanimity was easily explained, because the called-up doctors conducted regular medical examinations in factories and received money from their owners for this. And yet in 1819In 1999, Parliament passed a law banning the employment of children under the age of 9 in cotton mills and establishing a 12-hour working day for those under 16 years of age.

Finally, in the early 1830s, a movement began in the country to limit child labor. Among his inspirers, oddly enough, was the owner of the factory for the production of worsted fabric, John Wood, who could not expect any benefits from the campaign that had begun. One of the activists of the movement, Richard Oaster, recalled how it all began: “John Wood turned to me, shook my hand warmly and said: “Today I did not sleep all night. I read the Bible and every page condemned me. I won't let you leave until you promise to use all your influence to rid the factory system of all the cruelties we practice in our factories." Many, especially evangelicals, joined the movement for purely religious reasons, many for political reasons, such as MP John Hobhouse, who held radical views. Hobhouse introduced a bill in Parliament extending the provisions of the 1819 Actyears for all industries. The law was not passed then, but the struggle continued. Many members of the middle class, who were inspired by the novels of Charles Dickens, whose young heroes regularly suffered from the cruelty of the adult world, began to advocate for the restriction of child labor. Finally, workers who had an obvious economic interest joined the movement. Child labor was cheap, which brought down the price of adult labor, so that child care was beneficial to everyone who lived on one salary.

I read the Bible and every page condemned me. I won't let you leave until you promise to use all your influence to rid the factory system of all the cruelties we practice in our factories." Many, especially evangelicals, joined the movement for purely religious reasons, many for political reasons, such as MP John Hobhouse, who held radical views. Hobhouse introduced a bill in Parliament extending the provisions of the 1819 Actyears for all industries. The law was not passed then, but the struggle continued. Many members of the middle class, who were inspired by the novels of Charles Dickens, whose young heroes regularly suffered from the cruelty of the adult world, began to advocate for the restriction of child labor. Finally, workers who had an obvious economic interest joined the movement. Child labor was cheap, which brought down the price of adult labor, so that child care was beneficial to everyone who lived on one salary.

Soon, the children's protection movement had a clear leader - MP Michael Sadler. This man was perfect for this job. He was a Tory, that is, a defender of the interests of the aristocracy, so that the interests of the manufacturers did not bother him much. He had a strongly developed religious feeling. Suffice it to say that even in his youth he preached from the positions of the Methodist Church, for which representatives of the Anglican Church stoned him. Finally, he was a professional politician who had made a career of promoting socially oriented "poor laws" so that the workers knew and respected him. In 1832, Sadler headed a parliamentary commission investigating the state of child labor. The commission did a colossal job: factories were examined, children were interviewed, doctors were invited, ready to tell the truth. The final report was shocking, and in 1833 Parliament passed a law that limited the working day for the smallest (9-13 years old) 8 hours, and for seniors (14-18 years old) - 12 hours. But it extended only to the textile industry, so there was no complete victory.

This man was perfect for this job. He was a Tory, that is, a defender of the interests of the aristocracy, so that the interests of the manufacturers did not bother him much. He had a strongly developed religious feeling. Suffice it to say that even in his youth he preached from the positions of the Methodist Church, for which representatives of the Anglican Church stoned him. Finally, he was a professional politician who had made a career of promoting socially oriented "poor laws" so that the workers knew and respected him. In 1832, Sadler headed a parliamentary commission investigating the state of child labor. The commission did a colossal job: factories were examined, children were interviewed, doctors were invited, ready to tell the truth. The final report was shocking, and in 1833 Parliament passed a law that limited the working day for the smallest (9-13 years old) 8 hours, and for seniors (14-18 years old) - 12 hours. But it extended only to the textile industry, so there was no complete victory. And yet, since then, almost every five years, a law has been passed in England that in one way or another protected children from predatory exploitation. Finally, in 1878, the Factories and Workshops Act was passed, which for the first time forbade the employment of children under 10 years of age and extended this rule to all sectors of the British economy. At the same time, children under 14 could work no more than half the working day.

And yet, since then, almost every five years, a law has been passed in England that in one way or another protected children from predatory exploitation. Finally, in 1878, the Factories and Workshops Act was passed, which for the first time forbade the employment of children under 10 years of age and extended this rule to all sectors of the British economy. At the same time, children under 14 could work no more than half the working day.

This did not result in an economic collapse. Moreover, in the second half of the 19th century, the British economy felt very confident, and the wages of workers slowly but surely rose. Working parents could now provide their children with a piece of bread, and the need for child labor began to gradually disappear. All this, however, did not become possible until Britain had passed the initial stage of the industrial revolution.

Assembly salvo

Countries that lagged behind the UK in terms of industrial development later encountered the problem of child labor and later responded to it. Prussia was the first to regulate child employment, which banned in 1839employ children under 9 years of age. Other countries were not so quick: for example, the industrialized Belgium introduced such restrictions only in 1891. On the other side of the Atlantic, laws relating to child labor appeared a little earlier, but if in Prussia they were always strictly enforced, in the USA they were observed only when they really wanted to. For example, in Massachusetts, back in 1836, a law was passed according to which children under 15 years of age must spend at least three months a year in school. Naturally, no one followed the implementation of the law, just as no one followed the implementation of the law of the same state of 1842, which limited the work of children to 10 hours a day.

Prussia was the first to regulate child employment, which banned in 1839employ children under 9 years of age. Other countries were not so quick: for example, the industrialized Belgium introduced such restrictions only in 1891. On the other side of the Atlantic, laws relating to child labor appeared a little earlier, but if in Prussia they were always strictly enforced, in the USA they were observed only when they really wanted to. For example, in Massachusetts, back in 1836, a law was passed according to which children under 15 years of age must spend at least three months a year in school. Naturally, no one followed the implementation of the law, just as no one followed the implementation of the law of the same state of 1842, which limited the work of children to 10 hours a day.

The struggle for children's rights in the USA was dictated by approximately the same considerations as in England. There were religious moralists and ambitious politicians, but the main participants in campaigns for the protection of children were all the same hired workers who did not want underage competitors to bring down the price of labor. The initiative to restrict the labor of minors was taken up by the Working People Party, which in 1876 proposed a ban on the exploitation of children under 14 years old, the American Federation of Labor, which put forward a similar proposal in 1881, and many other organizations with frankly proletarian names. Individual states adopted separate laws, but in general, the matter did not move forward for a long time. Thus, the census of 1900 showed that half a million Americans aged 10 to 14 can neither read nor write, but are employed in the production process.

The initiative to restrict the labor of minors was taken up by the Working People Party, which in 1876 proposed a ban on the exploitation of children under 14 years old, the American Federation of Labor, which put forward a similar proposal in 1881, and many other organizations with frankly proletarian names. Individual states adopted separate laws, but in general, the matter did not move forward for a long time. Thus, the census of 1900 showed that half a million Americans aged 10 to 14 can neither read nor write, but are employed in the production process.

The public, as it should be, was indignant. In 1904, the National Committee on Child Labor was created in the United States, which fought for a happy childhood for all Americans. In 1908, the committee made an exceptional propaganda coup by sending an unknown schoolteacher, Lewis Hine, on a tour of the country. Hine was an amateur photographer, and during his two years of travel he collected a whole album of young textile workers, newspaper sellers, miners, shoe shiners and representatives of other professions. The captions under the photographs spoke for themselves: "Ferman Owens, 12 years old. Can't read. Doesn't know the ABCs. Says: 'Yes, I would like to study, but I can't because I'm at work all the time.'" Another caption read: “Some boys and girls are so small they have to climb onto looms,” and in the photograph itself, two boys of primary school age were balancing on a ledge of a loom that was twice their size. The photographs made a strong impression on contemporaries, and soon laws were passed in several states that limited the wage labor of minors. At 19In 16, the US Congress passed the Keating-Owen Act, which prohibited the sale of any goods in the production of which child labor was used. It was a major but temporary victory.

The captions under the photographs spoke for themselves: "Ferman Owens, 12 years old. Can't read. Doesn't know the ABCs. Says: 'Yes, I would like to study, but I can't because I'm at work all the time.'" Another caption read: “Some boys and girls are so small they have to climb onto looms,” and in the photograph itself, two boys of primary school age were balancing on a ledge of a loom that was twice their size. The photographs made a strong impression on contemporaries, and soon laws were passed in several states that limited the wage labor of minors. At 19In 16, the US Congress passed the Keating-Owen Act, which prohibited the sale of any goods in the production of which child labor was used. It was a major but temporary victory.

Not all Americans at that time believed that child labor was such a terrible evil. Least of all, of course, were the manufacturers, and especially the textile workers, inclined to agree with this. For example, the president of the Merchants Woolen Company, Charles Harding, believed that children belonged in a factory, not in a school: “There is a certain type of work that does not require much muscle strength and which a child can handle as well as an adult . .. Sometimes workers are too educated "I have seen many cases where an excess of education only spoils young workers." But among the supporters of child labor there were also indigenous proletarians. At 19In 1918, Roland Dagenhart, a North Carolina resident, challenged the Keating-Owen Act, which forbade his underage sons from working at the plant, through the courts. Dagenhart argued that Congress had violated his sons' constitutional right to work if they wanted to. The case reached the US Supreme Court, which found the act unconstitutional and overturned it, allowing thousands of children to return to their jobs.

.. Sometimes workers are too educated "I have seen many cases where an excess of education only spoils young workers." But among the supporters of child labor there were also indigenous proletarians. At 19In 1918, Roland Dagenhart, a North Carolina resident, challenged the Keating-Owen Act, which forbade his underage sons from working at the plant, through the courts. Dagenhart argued that Congress had violated his sons' constitutional right to work if they wanted to. The case reached the US Supreme Court, which found the act unconstitutional and overturned it, allowing thousands of children to return to their jobs.

The reason for the temporary defeat of the American fighters for the limitation of child labor was the same that prevented their English brethren from winning until 1878. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the United States had not yet reached a high level of industrial development, the country remained half agrarian, and it was too early to talk about the end of the industrial revolution. And while the industrial revolution is in full swing, no economy will want to abandon child labor. Only at 19In 1941, the decision in the Dagenhart case was reviewed and changed, and child labor was outlawed in the United States. But that was already a completely different era and a completely different America.

And while the industrial revolution is in full swing, no economy will want to abandon child labor. Only at 19In 1941, the decision in the Dagenhart case was reviewed and changed, and child labor was outlawed in the United States. But that was already a completely different era and a completely different America.

Call of the Jungle

After the Second World War, conventions and agreements came into fashion, which, according to their authors, are important for all mankind. In 1956, the UN adopted the Convention for the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, Institutions and Practices identical to Slavery, which included, in particular, the rejection of debt slavery. Indeed, in many of the then colonial states, children were given into debt slavery. However, after the adoption of the convention, the custom remained, as it remained after the independence of these countries. At 19In 1996, the well-known human rights organization Human Rights Watch released a report under the touching title "Little Hands of Slavery: Child Debt Slavery in India", and seven years later a new report - "Not Much Has Changed: Debt Slavery in India's Silk Industry". In general, child labor flourishes where it flourished in the time of Charles Dickens, in countries undergoing an industrial revolution.

In general, child labor flourishes where it flourished in the time of Charles Dickens, in countries undergoing an industrial revolution.

However, in countries where a full-fledged industrial revolution is still very far away, child labor is also intensively used. And some state child labor laws are so cleverly written that they can be easily circumvented. In Kenya, for example, the law strictly prohibits the employment of children under 16 in industrial enterprises, but allows them to be employed in the agricultural sector. Considering that there are not so many industrial enterprises in this country, the ban does not apply to anyone. Nepal is following the same path, where it is forbidden to hire persons under the age of 14, but the ban does not apply to plantations and brick-making enterprises. In addition to bricks, this country produces little.

Finally, on the world map there are countries like Togo, where children are not only forced to work, but even exported to neighboring countries. A human rights report states: "Togolese boys said they couldn't pay for school and agreed to go to farm work in Nigeria. According to them, they cleared land, plowed and sowed fields for 13 hours a day, complained of fatigue, they were beaten.Some were forced to cut tree branches with machetes, and many were seriously injured.After a period of eight months to two years, they were given a bicycle and ordered to go home to Togo.Boys were robbed by bandits, they had to bribe soldiers, and they returned home empty-handed. Some died and were buried along the road."

A human rights report states: "Togolese boys said they couldn't pay for school and agreed to go to farm work in Nigeria. According to them, they cleared land, plowed and sowed fields for 13 hours a day, complained of fatigue, they were beaten.Some were forced to cut tree branches with machetes, and many were seriously injured.After a period of eight months to two years, they were given a bicycle and ordered to go home to Togo.Boys were robbed by bandits, they had to bribe soldiers, and they returned home empty-handed. Some died and were buried along the road."

In a word, where there is poverty, there is also child labor, and no laws can help eradicate it. On the other hand, all industrialized countries that today can afford to do without it once went through the most brutal exploitation of their most vulnerable citizens. June 12 - World Day against Child Labor

Its purpose is to draw attention to this problem and the need for measures to eliminate it. Every year on June 12, governments, employers' and workers' organizations, civil society representatives, and millions of people around the world join forces to fight child labour.

In Russia, child labor has appeared relatively recently. Serious social changes and the economic crisis in the country have made it increasingly difficult for parents to control whether their children attend school, as well as organize their leisure time. Parents are unaware of the detrimental effect child labor has on a child's development. The phenomenon of child labor in Russia originates in the family. Often these are children from socially disadvantaged families or families who find themselves in a difficult life situation.

Tens of thousands of Russian children work at night, in the winter outdoors. They work, endangering their health, tired of carrying heavy loads. They work in places where not only any safety regulations are not followed, but there is a constant threat of abuse from adults. The latter especially concerns children involved in prostitution and illegal activities.

One of the most effective ways to prevent the involvement of young children in hard work is to set age limits, in accordance with which children can legally work and offer their services in the employment market. The main principles of the ILO Convention concerning the minimum age in employment and work are listed below.

The main principles of the ILO Convention concerning the minimum age in employment and work are listed below.

- Dangerous work

Any form of work that is likely to cause harm to the physical, mental or moral health of children, their safety or morals should not be performed by persons under 18 years of age. - Basic minimum age

The minimum age for entry into employment should not be before the completion of compulsory schooling, which is usually 15 years of age. - Light work

Children between the ages of 13 and 15 may perform light work as long as it does not endanger their health or safety or interfere with their education, career guidance and training. For the employment of a teenager in a children's clinic at the place of residence, a medical certificate is issued with restrictions on health reasons (or without restrictions) during employment.

There is a Department of Medico-Social Assistance in the St.