Giving birth on side

Evidence on: Birthing Positions - Evidence Based Birth®

System Pressures

There are many pressures in hospitals that limit caregivers from truly supporting birthing people. Too few nurses and increased charting duties limit nurses’ ability to perform intermittent auscultation or to provide hands-on support for different birthing positions—especially for patients with epidurals who require extra assistance.

If you have an epidural, you may need two assistants to help you move into certain positions, which is not possible if a hospital is short-staffed on nurses, or if the nurse is supposed to be charting on the computer every five to ten minutes for medical, legal, and insurance reasons.

If hospitals were willing to invest in more hands-on care to support birthing families, we would likely see more auscultation (instead of continuous EFM) and more staff support for position changes during labor, pushing, and birth.

Many birthing people find that one of the benefits of hiring an independent doula is that the doula can team up with other family members (such as the partner) to help you push and give birth in upright positions (whether you have an epidural or not). To read the evidence on doulas, visit https://evidencebasedbirth.com/doulas

Symbolic Importance of the Hospital Bed

Hospitals often invest tens of thousands of dollars in specialized birthing beds that can be broken down to support a range of positions (from lithotomy to hands and knees to squatting). The hospital bed takes a central location and importance in the typical hospital birthing room (almost throne-like in its placement), and each bed can cost anywhere between $4,000 and $10,000 USD.

The hospital bed itself is a potent symbol of the rite of passage of having a technologically driven birth. Anthropologist Robbie Davis-Floyd, PhD, writes that “Rituals transmit their meaning through symbols. A symbol is an object, idea, or action that is loaded with cultural meaning. Instead of being analyzed intellectually, a symbol’s message will be felt through the body and the emotions… Routine obstetric procedures are highly symbolic.” (Davis-Floyd, p. 49).

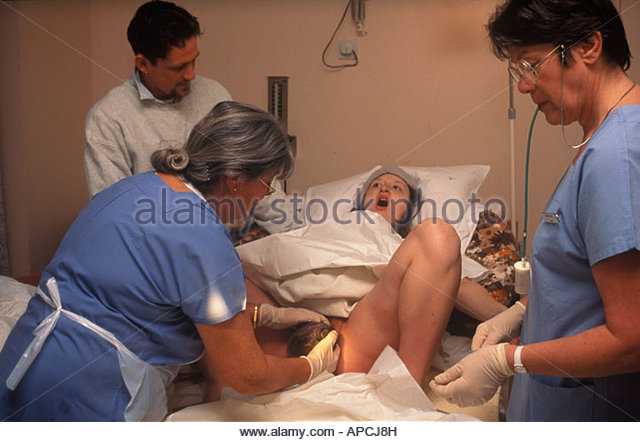

When a birthing person puts on a hospital gown and gets into the hospital bed, this symbol conveys that they are sick and need the technology and skills of the hospital staff. Then, when the hospital bed is combined with the lithotomy position (in which the birthing person is positioned with their legs up in the air and genitals exposed for everyone to see, with the practitioner standing over them), this can be seen as a symbol of powerlessness (for the birthing person) and status/authority (for the practitioner).

Then, when the hospital bed is combined with the lithotomy position (in which the birthing person is positioned with their legs up in the air and genitals exposed for everyone to see, with the practitioner standing over them), this can be seen as a symbol of powerlessness (for the birthing person) and status/authority (for the practitioner).

The significant financial, ritual, and symbolic meaning of hospital beds may help explain why hospital staff are so insistent that deliveries (whether upright or lying down) should always take place in bed.

In contrast, births that take place at home and in freestanding birth centers provide access to a variety of props, furniture, and tools. These environments encourage upright birthing, with the purpose of facilitating physiological birth and empowering the birthing person.

In the first randomized controlled trial of its kind (still ongoing at the time we updated this article) researchers in Germany are studying changes to hospital birthing rooms that encourage upright positions and enhance relaxation and comfort (Ayerle et al. 2018). In the “intervention group,” birthing people have access to a room that includes:

2018). In the “intervention group,” birthing people have access to a room that includes:

- Bed that is absent or hidden from sight

- Mattress and foam mat on the floor

- Bean bag or easy chair

- Foam element shaped like a birthing stool

- Snack bar with table and chairs

- Posters showing upright positions

- Monitor showing natural sounds/music

- Sign on the door requesting privacy

In the “control” group, the delivery bed has a central place in the room and is accessible from three sides. A birthing stool, birth ball, and length of fabric suspended from the ceiling (to use for support while standing/squatting) remain available as is usual in some hospitals in Germany.

The results from this study, known as the “BE-UP” trial, have not yet been published. The researchers plan to examine the effects of the birthing rooms on Cesarean rates, episiotomy rates, perineal tears, epidural use, newborn health, and maternal feelings of self-determination.

A similar study, known as the “Room4Birth” trial, is also taking place in Sweden (Berg et al. 2019).

So, what’s the actual research evidence on birthing positions?

Because most researchers study birthing positions only in people without epidurals, or only in those with epidurals, we will divide the research up based on epidural use.

Without epidurals, which birthing positions are best supported by evidence?In a systematic review and meta-analysis published by Zang et al. (2020), researchers combined 12 randomized, controlled trials with 4,314 participants who were randomly assigned to upright vs. recumbent birth.

The researchers excluded any studies that used the lithotomy position because of its known harms and increased risks. They stated, “these horizontal positions can have serious negative effects on maternal health and are not recommended by many international organizations.” As a result, this review is smaller than the Cochrane review and meta-analysis by Gupta et al. (2017), which included the lithotomy position and thus had a larger number of participants.

(2017), which included the lithotomy position and thus had a larger number of participants.

The Zang et al. team followed the PRISMA guidelines for reviews (https://prisma-statement.org/ ), and they included studies that had participants with low-risk pregnancies at 37-42 weeks. Participants had to be pregnant with a single baby in spontaneous labor, and they could not have an epidural.

The researchers compared upright versus recumbent positions.

- They defined “upright” as walking, standing, leaning, using a birth chair, semi-sitting, squatting, and kneeling.

- However, none of the included studies used semi-sitting as an upright position.

- Upright birthing positions were used only in the passive pushing phase in 4 studies, only in the active pushing phase in 3 studies, and in the entire second stage in 7 studies.

- The reviewers defined recumbent as lateral (side-lying), supine (lying), or semi-recumbent (lying with the head of the bed raised up).

The studies in the Zang et al. review took place in the United Kingdom (U.K.), Finland, Brazil, China, Ireland, Turkey, and South Africa, and the publication dates ranged from 1983 to 2017. Unfortunately, the risk of bias was unclear in 8 studies, and the risk of bias was high in 4 studies. Most of the studies had problems with randomization (selection bias), blinding (detection bias), and a few studies had problems with attrition (people dropping out of the study). As such, we need to take this review’s findings with caution.

Zang et al. found that upright birthing positions led to:

- Lower rate of instrumental delivery (forceps/vacuum use)

- Shorter length of the active pushing phase (by 8 minutes on average)

- A much shorter length of the active pushing phase when squatting was used (by 16 minutes on average)

- Substantial decrease in the risk of severe perineal trauma (75% relative risk reduction; only 2 of the 12 studies reported on severe perineal trauma)

- Higher risk of 2nd degree tears with the positions of squatting and sitting on a birth seat

- No difference in blood loss of >500 mL between groups (in contrast to earlier reviews that found a higher risk of blood loss in upright groups)

- No difference in the length of the entire second stage

The effect of birthing positions on episiotomy rates was unclear because the studies had a wide range of episiotomy rates. For example, some studies had episiotomy rates closer to 0% in both groups, while some studies had episiotomy rates of close to 90%. Because all the studies were so different, it wasn’t possible to combine the results on episiotomy.

For example, some studies had episiotomy rates closer to 0% in both groups, while some studies had episiotomy rates of close to 90%. Because all the studies were so different, it wasn’t possible to combine the results on episiotomy.

Some people may be surprised to see the higher risk of 2nd degree tears with squatting or using a birth seat. But this can be explained by the fact that in these studies, the higher rate of 2nd degree tears with upright births was exchanged for a lower rate of episiotomies. Since other researchers have found strong evidence that natural tears heal easier and are less traumatic to tissue than episiotomies (Jiang et al., 2017), a higher risk of second-degree tear in exchange for a lower risk of episiotomy is considered a good trade-off.

Previous researchers (Gupta et al., 2017) have noticed a higher risk of blood loss with upright birth, but this was not seen in the Zang et al. (2020) meta-analysis.

Other outcomes, such as pain, satisfaction, or use of Pitocin® to augment labor, were not examined in the Zang meta-analysis. However, results from individual randomized, controlled trials, have found additional benefits to upright birth.

However, results from individual randomized, controlled trials, have found additional benefits to upright birth.

For example, in 2017, Moraloglu et al. published a study with 102 people giving birth without epidurals in Turkey. Participants in this study were randomly assigned to push and give birth in a standing/squatting position holding onto a bar, or the lithotomy position with the head of the bed raised 45 degrees. The study showed that those who stood, then squatted down with a bar to push during contractions, had shorter second stages of labor by about 34 minutes. They also experienced less pain, were less likely to receive Pitocin® to augment labor, and had higher satisfaction with the birth experience, compared with the group that pushed and gave birth while back-lying with the head of the bed raised.

Other individual randomized trials have found that in people without epidurals, upright birthing positions lead to:

- Significantly lower rates of pain (de Jong et al.

1997; Purnama et al. 2018)

1997; Purnama et al. 2018) - Lower rates of shoulder dystocia (Zhang et al. 2017)

- Lower rates of abnormal fetal heart tones (Crowley et al. 1991; de Jong et al. 1997)

- Lower rates of emergency Cesarean (Zhang et al. 2017).

For people

with epidurals, which birthing positions are best supported by evidence?Epidural analgesia is common in many countries; for example, more than 60% of those giving birth to a single baby in the U.S. use epidural or spinal analgesia (ACOG, Practice Bulletin No. 177, 2017).

In 2018, Walker et al. published a Cochrane review that examined the evidence for upright vs. non-upright birthing positions among people with epidurals. However, since this review was dominated by BUMPES randomized trial (more than three-fourths of the Cochrane review participants came from this trial), I chose to write about the BUMPES trial instead of the Walker et al. Cochrane review.

The BUMPES trial on side-lying with an epidural vs.

upright with an epidural

upright with an epiduralThe BUMPES trial was a very large randomized, controlled trial on birthing positions carried out by a group of researchers in the U.K. called the Epidural and Position Trial Collaborative Group (2017). The researchers compared upright vs. side-lying birthing positions in first-time birthing people, all of whom had a low-dose epidural.

Between 2010 and 2014, a total of 3,236 people were enrolled in the study from 41 centers in the U.K. To be included in the study, participants had to be over the age of 16, pregnant with a single, head-down baby at 37 weeks or greater, planning to give birth vaginally, and in the second stage of labor with a low-dose epidural.

Since participants weren’t randomized to upright or side-lying positions until the second stage of labor, this research doesn’t apply to positioning with epidurals in the first stage of labor. It also doesn’t tell us anything about the back-lying, semi-sitting, or lithotomy positions with an epidural.

The upright group was assigned to be moving on foot, standing, sitting, kneeling, or in any other upright position.

The non-upright group was assigned to side-lying with the head of the hospital bed raised up 30 degrees. Because they were all supposed to use the side-lying position, we will call this group the side-lying group.

About 80% of participants assigned to both the upright and side-lying groups were able to move around, meaning that they had true low-dose epidurals. For the most part, people used their assigned pushing positions.

The researchers found that fewer people assigned to upright birthing positions experienced spontaneous vaginal birth compared to people in the side-lying group (35% vs. 41%). Most participants in this study gave birth either with Cesarean or with vacuum/forceps. We were surprised to see such high rates of intervention in this study—the rate of vacuum/forceps births was 51%-55% and more than half (55%-59%) of people received an episiotomy—a procedure that is known to increase harms. These numbers are very high. In the U.S., for example, the overall rate of vacuum/forceps births is only around 3% (Martin et al., 2017).

These numbers are very high. In the U.S., for example, the overall rate of vacuum/forceps births is only around 3% (Martin et al., 2017).

It’s not clear why people assigned to upright birthing positions were less likely to have spontaneous vaginal births in this study. The researchers did not find a difference between groups in rates of failure to progress or fetal distress leading to vacuum or forceps. They also did not find differences in any other health outcomes. It could be that people with low-dose epidurals have a greater chance of giving birth spontaneously when they use a side-lying position for the second stage of labor rather than an upright position. However, the findings from this study should be taken with extreme caution—the results may not apply to settings with more support for spontaneous vaginal birth (where there is less use of vacuum or forceps).

In two other randomized trials, researchers found evidence that the lithotomy position is harmful if you have an epidural.

In the first study on the lithotomy position with epidurals:

- Researchers randomly assigned 199 participants giving birth at a hospital in Spain to a “traditional model of birth” or an “alternative model of birth” (Walker et al., 2012).

- People assigned to the traditional model began pushing in the lithotomy position immediately after they reached ten centimeters and gave birth in the lithotomy position.

- People assigned to the alternative model delayed pushing and gave birth in a specific type of side-lying position:

- The alternative model group was instructed to change position every 20-30 minutes after reaching full dilation and begin active pushing efforts only after feeling a strong urge to push.

- Hospital staff assisted them in moving into different positions like sitting, kneeling, side-lying, or hand-and-knees.

- If, after 2 hours in the passive phase, the epidural prevented people from feeling an urge to push, they were asked to start pushing with each contraction.

- When people in the delayed pushing group were ready to begin pushing efforts, staff assisted them into a specific side-lying position. In this position, the lower leg remained extended on the bed and the upper leg rested flexed on the stirrup. This placed the foot of the upper leg in a higher position than the knee to allow the upper hip to rotate. The birthing person’s upper body was placed in a neutral position and supported with pillows, if necessary.

- Those who delayed pushing and gave birth in a side-lying position were less likely to need forceps, vacuum, or fundal pressure (20% vs. 42%) and had a higher rate of intact perineum (40% vs. 12%) compared to people who pushed immediately and delivered in a lithotomy position.

- There was no difference between groups in the rate of first-, second-, or third-degree perineal tears, so the lower rate of episiotomy (21% vs. 51%) in the side-lying group accounts for the higher rate of intact perineum in that group.

In the second study on lithotomy positions with epidurals:

- Researchers randomly assigned 150 birthing people in Spain to position changes every five to 30 minutes in the passive phase of the second stage of labor or to a lying down position for the entire second stage (Simarro et al., 2017).

- Both groups were instructed to delay pushing and everyone eventually gave birth in the lithotomy position.

- The people assigned to position changes during the passive phase of the second stage of labor had better outcomes than the group that was lying down for the entire second stage, even though everyone gave birth in the same back-lying position.

- The group that changed positions had fewer Cesareans (1% vs. 10%) and fewer cases of vacuum/forceps (24% vs. 39%). They also experienced shorter second stages of labor (95 minutes vs. 124 minutes) and fewer episiotomies (18% vs. 31%).

In other words, evidence continues to show today that the lithotomy position is harmful and should not be used for pushing or delivery, even in with people with epidurals.

Evidence on Birth Seats (for people with and without epidurals)

Birth seats or stools have been used for thousands of years. For example, they are mentioned in the book of Exodus 1:16:

“When you serve as midwife to the Hebrew women and see them on the birthstool…”

Recently, researchers have begun exploring the effectiveness of different types of birth stools.

The Swedish Birth Seat Trial was carried out at two hospitals in Sweden between 2006 and 2009

(Thies-Lagergren, 2013). The study included 1,020 participants giving birth vaginally for the first time between 37 weeks and 41 weeks 6 days. Nearly half (45%) used epidurals for pain relief during labor. Participants were randomly assigned to either give birth on a special birthing seat called the BirthRite seat (http://bit.ly/2FBk5a8) or in any other position.

The researcher found:

- The birth seat resulted in a shorter second stage of labor by an average of 6-13 minutes, as well as less use of Pitocin® for augmentation of labor.

- No difference in the rate of forceps or vacuum assistance.

- People who gave birth on the birth seat were at increased risk of postpartum blood loss; however, the blood loss did not influence hemoglobin levels 2-3 months postpartum.

- There was no difference between the groups as far as perineal tears, but the birth seat was linked to fewer episiotomies—2% of those who gave birth on the birth seat had an episiotomy compared to 14% of those who gave birth in other positions.

The study did not find a difference in health outcomes for mothers or infants other than the increase in postpartum blood loss. However, the participants who were assigned to give birth on the birth seat were more likely to report that they felt “powerful, protected and self-confident”—which led to greater satisfaction with childbirth.

To watch a video from Evidence Based Birth® that shows different types of birthing stools, visit here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbHujklthyo

What evidence do we have on birthing positions from observational studies?

We found three observational studies on birthing positions in the second stage of labor that have been published in the last ten years—two from Sweden and one from Italy.

Swedish Study compared “women-centered” care to standard care

The first study from Sweden looked at strategies care providers can use in the second stage of labor to improve health outcomes (Edqvist et al., 2017). Midwives treated 296 first-time birthing people with a three-part protocol called “woman-centered care,” and the other 301 first-time birthing people received standard care. The use of epidurals in the study was 61%.

The group that received woman-centered care had:

- Spontaneous pushing (pushing efforts were not coached or directed),

- Flexible sacrum birthing positions (kneeling, standing, hands-and-knees, side-lying, birth seat)

- Birth of the baby’s head and shoulders in two separate contractions (for more about this evidence-based method, called the “two-step delivery method,” listen to EBB Podcast Episode 168)

In contrast, the midwives who practiced standard care did not receive any special instructions.

The researchers determined that the odds of second-degree tears were less likely in those who received woman-centered care compared to those who received standard care. However, we do not know which part of the 3-part protocol contributed to the lower rate of second-degree tears.

However, we do not know which part of the 3-part protocol contributed to the lower rate of second-degree tears.

Swedish study looks at birthing positions and severe tears

Another study also from Sweden looked at the effect of delivery position on the rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) (Elvander et al., 2015). These severe tears, also called third- and fourth-degree perineal tears, are related to long-term complications, such as anal incontinence, sexual dysfunction, pain, and a reduced quality of life.

The researchers included more than 100,000 people from a birth record database in the study. The database included midwives’ records of which position the birthing person used during the actual birth. More than half (57%) of the first-time birthing people used epidurals and 26% of those who had given birth before used epidurals. Everyone included gave birth vaginally to a single baby, and no episiotomies were used.

The researchers found that the lowest rates of severe perineal tears occurred among people who delivered in a standing position, and the highest rates of severe tears occurred among those who delivered in the lithotomy position.

Italian study looks at birthing position and urinary incontinence

In another study, researchers in Italy explored what effect birthing positions may have on urinary incontinence (Serati et al., 2016). They conducted phone interviews 12 weeks after the birth with 296 people who used an upright position to deliver and 360 people who used a back-lying or side-lying position. To assess urinary function, participants were asked questions like: How often do you leak? How much urine do you usually leak? When does the urine leak?

The survey data showed that delivering in upright positions was related to a lower episiotomy rate (30% vs. 41%) but a slightly higher rate of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears compared to delivering in the lying down position (1.35% vs. 0%). The episiotomy rate in this study was very high, so these results may not apply to low-episiotomy settings.

Importantly, these Italian researchers found that lying down delivery positions increase the risk for postpartum urinary incontinence and of stress urinary incontinence, defined as involuntary leakage on effort or exertion or sneezing or coughing. It’s possible that this increase in the risk of urinary incontinence may be related to the higher rates of episiotomies with lying down positions.

It’s possible that this increase in the risk of urinary incontinence may be related to the higher rates of episiotomies with lying down positions.

In my discussions with professionals and parents around the world, I have heard that some providers may be willing to support pushing in upright positions (passive or active second stage), but few obstetricians will attend an actual birth or “delivery” in an upright position.

For example, health care workers may support someone pushing in a squatting position, but when the baby is about to emerge, they may insist the birthing person sit back in a semi-sitting or lying back position for the delivery. They may say something like, “I need you to get onto your back right now for safety reasons” or “You don’t want to tear, do you? Then get on your back right now,” or “Your baby is going to get stuck under your pubic bone, unless you move right now!”

In other words, it’s common to be given a vague threat combined with an urgent direction. This situation can be confusing, because parents may think it is a true emergency (which is a possibility, of course), so they almost always comply… but many times it is not an emergency, and there is nothing wrong with the birth or baby.

This situation can be confusing, because parents may think it is a true emergency (which is a possibility, of course), so they almost always comply… but many times it is not an emergency, and there is nothing wrong with the birth or baby.

The coercion that some providers use to get patients to lay on their back may be due to general anxiety and fear of upright birth. Since most health care workers are not trained in true upright birth, and rarely (if ever) see one, an upright birth may make them feel nervous and uncomfortable. The easiest way to relieve these feelings of discomfort is to pressure the patient to lay on their back.

The desire for some medical staff to have the delivery happen in a “controlled” manner (non-upright position) is so strong that many birthing people have shared stories with us of either being coerced or forcibly put into non-upright positions during childbirth.

In 2016, Caroline Malatesta won a landmark court case in Alabama in which she sued her hospital for malpractice and fraud. At Ms. Malatesta’s birth, the hospital nurses forcibly turned her onto her back (she was in a hands-and-knees position) during the delivery and held the baby’s head in for 6 minutes until the doctor could arrive, causing a severe, lifelong, maternal nerve injury. The jury awarded a $16 million verdict in Ms. Malatesta’s favor, finding that forcing a birthing person into a delivery position against their will violates the nursing standard of care, especially for un-medicated or “natural” births.

At Ms. Malatesta’s birth, the hospital nurses forcibly turned her onto her back (she was in a hands-and-knees position) during the delivery and held the baby’s head in for 6 minutes until the doctor could arrive, causing a severe, lifelong, maternal nerve injury. The jury awarded a $16 million verdict in Ms. Malatesta’s favor, finding that forcing a birthing person into a delivery position against their will violates the nursing standard of care, especially for un-medicated or “natural” births.

The use of forcing birthing people into the care provider’s preferred position is a form of obstetric violence. In their paper describing Ms. Malatesta’s case in the Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, Pascucci and Adams (2017) state:

Obstetric violence is, in its simplest form, a form of violence against women that occurs in the childbirth setting. It is an attempt to control a woman’s body and decisions and may involve coercion, bullying, threats, and withdrawal of support, as well as other violations of informed consent and physical force. Obstetric violence might manifest as forcing a woman supine because that is the doctor’s preferred position for birth… Forcing someone into a particular delivery position could be viewed by the courts as negligence or battery (Pascucci and Adams, 2017).

Obstetric violence might manifest as forcing a woman supine because that is the doctor’s preferred position for birth… Forcing someone into a particular delivery position could be viewed by the courts as negligence or battery (Pascucci and Adams, 2017).

It is best practice for hospitals, obstetric providers, and nurses to support birthing people in their right to choose positions for pushing and delivery. This does not mean that providers cannot encourage certain positions (or frequent switching of positions) if they feel that they would be helpful in specific situations—but it is unethical for a provider to use coercion or force to achieve a delivery position.

Listen to Evidence Based Birth® Podcast Episode 225 with Mandy Irby, RN, about how the lithotomy position can also be considered an unethical “restraint.”

In a publication by the World Health Organization (WHO) called “Care in Normal Birth,” the WHO concludes that women in labor should adopt any position they like, while preferably avoiding long periods lying down (WHO, 1996). They recommend that birth attendants get training in supporting upright births, since much of the positive effect of upright birthing positions depends on the birth attendant’s experience with the position and willingness to support the patient’s choice of position.

They recommend that birth attendants get training in supporting upright births, since much of the positive effect of upright birthing positions depends on the birth attendant’s experience with the position and willingness to support the patient’s choice of position.

In 2017, the World Health Organization also published a document called “Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth,” in which they stated the health care provider should “support the woman’s choice of position during labor and birth.”

In the U.S., the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has a Committee Opinion called “Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth.” In this opinion, ACOG states that for most people, “no one position needs to be mandated nor proscribed.”

ACOG also states that it is normal for people in labor to assume many different positions, and that no one position has been proven best. They cite the fact that many care providers encourage a supine position during labor even though it has known adverse effects, including low maternal blood pressure and more frequent abnormal fetal heart rates. They go on to say that continuous EFM has not improved outcomes in low risk pregnancies, and that care providers should “consider training staff to monitor using a hand-held Doppler device (intermittent auscultation)…which can facilitate freedom of movement and which some women find more comfortable.”

They go on to say that continuous EFM has not improved outcomes in low risk pregnancies, and that care providers should “consider training staff to monitor using a hand-held Doppler device (intermittent auscultation)…which can facilitate freedom of movement and which some women find more comfortable.”

The statement concludes with a general recommendation that care providers can support frequent position changes during labor to enhance maternal comfort and promote optimal positioning of the baby if they do not hinder monitoring and there are no complications.

In 2012, three U.S. midwifery organizations –American College of Nurse Midwives, Midwives Alliance of North America, and National Association of Certified Professional Midwives—created a consensus statement on supporting healthy, physiologic childbirth (U.S. Midwives, 2012). They stated that freedom of movement in labor and the woman’s choice of birth position are essential to this goal.

The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) in the U. K. recommends the use of active and upright positions to assist with labor and delivery. In their guidelines, they urge midwives to be proactive in demonstrating and encouraging different positions in labor, since birthing people often “choose” to do what is expected of them, and the most common image of the laboring person is “on the bed.”

K. recommends the use of active and upright positions to assist with labor and delivery. In their guidelines, they urge midwives to be proactive in demonstrating and encouraging different positions in labor, since birthing people often “choose” to do what is expected of them, and the most common image of the laboring person is “on the bed.”

Since the environment is key to freedom of movement, RCM suggests that there should be a variety of furniture and props available in the room to encourage people to try different positions: bean bags, mattresses, chairs, and birth balls. They recommend that midwives support clients with suggestions on how to remain upright even if they’re in a situation that might limit mobility—such as with traditional EFM, intravenous (IV) fluids, and different medications for pain relief.

13 Best Labor and Birthing Positions

For nine months you prep and plan for baby’s arrival. You read books, watch videos and maybe even take a birthing class or two. But while movies and TV shows have led many of us to believe both labor and delivery happen while lying on your back with your legs spread wide, anyone who’s been through the experience will tell you it doesn’t have to play out that way.

But while movies and TV shows have led many of us to believe both labor and delivery happen while lying on your back with your legs spread wide, anyone who’s been through the experience will tell you it doesn’t have to play out that way.

There are actually a variety of labor positions you can assume during the first phases of childbirth and a whole other set that makes for good birthing positions when it’s time to push—and they don’t all call for you to be flat on your back. “Rotating between different labor and birthing positions is important to optimize conditions for the mom and baby,” says Sara Twogood, MD, an obstetrician gynecologist at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and author of Ladypartsblog.com. “For Mom, this could mean making her more comfortable, especially if she’s having a medication-free birth. It can also mean maximizing the space in her pelvis so baby has more room.”

Here’s a primer on some of the best labor and birthing positions to help you prepare for the big day.

In this article:

Best labor positions

Best birthing positions

Best Labor Positions

The process of giving birth takes work (it’s not called “labor” for nothing). But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t find a way to be as comfortable as humanly possible. “Labor positions are used during the labor process to help ease discomfort, move the baby down through the pelvis and encourage optimal fetal positioning,” says Lindsey Bliss, a birth doula and co-director of Carriage House Birth in New York City. “If you end up choosing not to utilize drugs for pain management, labor positions are essential for easing discomfort.”

Active labor, the phase in which contractions come on strong, is often when things really start to hurt. But keep in mind that women don’t start pushing until the cervix is fully dilated—for some women, this happens quickly; for others, not so much. So as your body and baby prepare for delivery, there are several labor positions your doctor or midwife may suggest to get you to the pushing point more comfortably. “Labor and delivery nurses are usually really great at helping a woman move around, even with an epidural, to find the labor positions that feel best for them,” Twogood says. “I recommend women try out a number of positions during labor. Every woman and baby is different, and what works for one woman won’t be ideal for another.”

“Labor and delivery nurses are usually really great at helping a woman move around, even with an epidural, to find the labor positions that feel best for them,” Twogood says. “I recommend women try out a number of positions during labor. Every woman and baby is different, and what works for one woman won’t be ideal for another.”

Check out some of the most common labor positions:

The hands and knees position

The all fours position calls for you to get down onto your hands and knees, either in bed or on a floor mat. “The hands and knees position is a great one, since it helps open the pelvis,” says Rebekah Wheeler,** RN, CNM, is a certified nurse-midwife in the Bay Area, California. . Adds Megan Cheney, MD, MPH, medical director of the Women’s Institute at Banner University Medical Center in Phoenix, “Sometimes baby’s heart rate responds better when you’re in the hands and knees position, especially if baby isn’t in the best spot.”

Pros:

Cons:

- Your arms may get tired

The sitting position

When you feel baby’s weight bearing down, you may just want to sit down—and that’s okay. Whether it’s in a birthing chair or even on a toilet, sitting and spreading your legs in this labor position can relieve some of the pressure on your pelvis.

Whether it’s in a birthing chair or even on a toilet, sitting and spreading your legs in this labor position can relieve some of the pressure on your pelvis.

Pros:

- Good for resting

- Can still be used with a fetal monitoring machine

- Sitting on a toilet relaxes the perineum, which can help reduce tearing

Cons:

- A hard toilet seat can become uncomfortable

- May not be an option if you’ve had high blood pressure during pregnancy

Birthing ball positions

Besides sitting on a birthing chair or toilet, you can also work the birthing ball into your labor positions. There are more than a few women who hail the prop as their BFF during labor and delivery. “Birthing balls provide support while you shift around,” Twogood says. “Women who want movement in their hips seem to find them helpful.” You can use a birthing ball in several ways: Some women sit or rock on it, lean against it or simply drape their upper bodies over it while kneeling. It can even be used as support while squatting. “I’m a huge fan,” Bliss says. “It’s great because women can continue bouncing and moving through the contractions even while being monitored.” Check beforehand to see if your hospital uses wireless fetal monitors; if not, you’ll be limited in how far you can move in these labor positions.

It can even be used as support while squatting. “I’m a huge fan,” Bliss says. “It’s great because women can continue bouncing and moving through the contractions even while being monitored.” Check beforehand to see if your hospital uses wireless fetal monitors; if not, you’ll be limited in how far you can move in these labor positions.

Pros:

-

Can help move baby into a favorable birthing position

-

Relieves back pressure

-

Birthing ball labor positions can help encourage dilation and move baby deeper into the pelvis

Cons:

The squatting position

Squats rarely top anyone’s list of favorite exercises, but on the day you give birth, you may want to give them a try as one of your labor positions. Squatting can be done against a wall or with the support of a chair or partner.

Pros:

Cons:

- May become tiring

The side-lying position

Lying on your side is one of the best labor positions to try when you need a rest. That said, just because you’re lying down doesn’t mean your body is taking a break from labor; on the contrary, it can actually help baby move into the ready position. “Side-lying and using a peanut-shaped birthing ball between the legs are wonderful tools for getting baby to descend and rotate,” Bliss says. “I encourage my clients to flip from side to side during the process to help baby come down and out.”

That said, just because you’re lying down doesn’t mean your body is taking a break from labor; on the contrary, it can actually help baby move into the ready position. “Side-lying and using a peanut-shaped birthing ball between the legs are wonderful tools for getting baby to descend and rotate,” Bliss says. “I encourage my clients to flip from side to side during the process to help baby come down and out.”

Pros:

-

Helps get oxygen to baby

-

Can be used if you have high blood pressure

-

Makes it easier to relax during contractions

Cons:

- May be difficult to assess fetal heartbeat

The upright position

Gravity may not be your best friend during pregnancy, but you can make it work to your advantage during childbirth through upright labor positions. Whether you’re standing, walking or swaying, simply being vertical can get you closer to the finish line. “Walking can be helpful for women who are waiting for labor to progress,” Cheney says. Amy, a mother of two from Connecticut, found that to be the case. “I walked laps around the hospital wing to speed things up,” she says. Swaying while using another person as support is also a good way to work through labor. “Rocking your hips keeps baby moving lower and lower,” Wheeler says. (It’s also good for getting a final hug of support from your partner before the main event!) Here are some other things to consider when it comes to the upright position:

“Walking can be helpful for women who are waiting for labor to progress,” Cheney says. Amy, a mother of two from Connecticut, found that to be the case. “I walked laps around the hospital wing to speed things up,” she says. Swaying while using another person as support is also a good way to work through labor. “Rocking your hips keeps baby moving lower and lower,” Wheeler says. (It’s also good for getting a final hug of support from your partner before the main event!) Here are some other things to consider when it comes to the upright position:

Pros:

Cons:

The lunging position

Doing lunges during labor may not sound like your idea of a good time, but lunging is one of the labor positions you may want to give a whirl. Unlike at the gym, you can put your foot up on a chair for these lunges: Simply lean your body forward onto the raised foot when you feel a contraction coming on. You can repeat it as many times as you want.

Pros:

Cons:

- Requires a partner to help you keep your balance

The stair-climbing position

If labor has been progressing nicely and then starts to slow down, baby might need extra encouragement to slip into the optimal position for birth. You may want to consider climbing stairs as one of your labor positions, since it can help baby shift.

Pros:

Cons:

- Can be tiring, especially if you’ve been in labor for a while

Best Birthing Positions

You’ve made it through the first stages of labor—congrats! Now it’s time to switch things up and assume birthing positions for the final stretch. “Birthing positions are used to push baby out,” Bliss says. Like labor positions, birthing positions don’t always equal lying on your back. In fact, “women who are in bed tend to experience more pain than women who move around,” Wheeler says. Here are some of the best birthing positions to try.

Squatting birth positions

Squats aren’t only great to do during labor, but they’re also among the popular birthing positions. Remember, when it comes to labor and delivery, gravity is on your side.

Pros:

Cons:

Reclining birth positions

Childbirth is hard work, and you might need to take a break—which is why many women opt for reclining birthing positions. Keep in mind, “reclining” can mean a number of things—yes, you can lie down in bed, but you can also recline against a wall, a chair or another person.

Pros:

- Can release tension and relax the muscles

- May be a good alternative if a woman is tired but doesn’t want to lie down completely

Cons:

- Can work against gravity

Birthing stool positions

A birthing stool can be used in a variety of birthing positions: Women can squat on it, get in the all fours position and use it to support the arms or even rock back and forth with it, depending on the design of the stool. Bonus: If you like the idea of a water birth, there are some birthing stool models that work in the water.

Bonus: If you like the idea of a water birth, there are some birthing stool models that work in the water.

Pros:

-

Can help baby move farther down

-

Relieves stress on the back

-

Can increase dilation of the cervix

Cons:

- Women may experience increased blood loss

Birthing bar positions

Call it the birthing stool’s cousin: The birthing bar is an attachment that can be added to many labor beds to help support birthing positions. With a birthing bar, you can sit up at any time and squat, leaning on the bar for support. “The birthing bar can be an awesome tool. You can wrap a towel on it to make it easier to use and switch positions,” Wheeler says. That proved to be true for Jennifer, a mom of two from Connecticut, who recalls that “after about two hours of pushing with no success, the birthing bar was put on the bed. It helped me get the resistance I needed to push to the point where the doctor could intervene. ”

”

Pros:

Cons:

- May not be available at all hospitals

Kneeling birth positions

If baby is facing Mom’s abdomen instead of her back, kneeling can help them turn to get into the proper position. Kneeling is one of the most popular birthing positions because it also gives mom a much-needed break.

Pros:

Cons:

- May be difficult for continuous fetal monitoring

When it comes to labor and birthing positions, discuss all options with your doctor or midwife to land on the ones that will be most comfortable and practical for you. “Every baby and mom responds to positions differently. It’s the job of the labor assistant to help figure out what works best,” Wheeler says. Whichever labor and birthing positions you choose, it’ll all be worth it when baby is finally placed in your arms.

Updated February 2020

Expert bios:

Sara Twogood, MD, FACOG, is a board certified obstetrician-gynecologist at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Previously, she held a faculty appointment at USC Keck School of Medicine and practiced general OBGYN in an affiliated private practice. Twogood is also the author of Ladypartsblog.com, which covers topics relating to fertility and pregnancy, and the founder of FemEd, a program designed to empower females through health education.

Previously, she held a faculty appointment at USC Keck School of Medicine and practiced general OBGYN in an affiliated private practice. Twogood is also the author of Ladypartsblog.com, which covers topics relating to fertility and pregnancy, and the founder of FemEd, a program designed to empower females through health education.

Lindsey Bliss is a birth doula and co-founder of Carriage House Birth, a doula agency established in New York City in 2012 that now serves Los Angeles as well.

Rebekah Wheeler, RN, CNM, MPH, is a certified nurse-midwife in the Bay Area, California. She is the founder of the Malawi Women’s Health Collective, a small non-profit organization, and has served on the boards of the California Nurse-Midwifery Association, Planned Parenthood of Rhode Island and the Women’s Health and Education Fund of Southeastern Massachusetts. She holds a Master’s of Public Health and a Master’s of Science in Nursing from Yale University.

Megan Cheney, MD, MPH, is an ob-gyn and the medical director of the Women’s Institute at Banner University Medical Center in Phoenix, Arizona. She earned her medical degree from University of Arizona College of Medicine in 2009.

Please note: The Bump and the materials and information it contains are not intended to, and do not constitute, medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. You should always consult with a qualified physician or health professional about your specific circumstances.

Plus, more from The Bump:

4 Must-Know Strategies for an Easier Labor and Delivery

5 Medication Options for Pain Relief During Labor

What to Expect During the Different Stages of Labor

What is a vertical birth?

If you believe the ancient sources, then only the last 200-300 years, women give birth lying down. And if we turn to history, then from time immemorial they gave birth, either sitting on their knees or squatting, or in a standing position. This did not bypass Kievan Rus. The daughter of Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich and Christina of Sweden, Princess Evpraksia Mstislavovna Dobrodeya, recorded in her medical book historical and her own observations of obstetric care. Subsequently, having become the Byzantine empress under the name Zoya, she also became the first Russian author who outlined the issues of obstetrics in her writings, including “vertical” childbirth. nine0003

This did not bypass Kievan Rus. The daughter of Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich and Christina of Sweden, Princess Evpraksia Mstislavovna Dobrodeya, recorded in her medical book historical and her own observations of obstetric care. Subsequently, having become the Byzantine empress under the name Zoya, she also became the first Russian author who outlined the issues of obstetrics in her writings, including “vertical” childbirth. nine0003

It was noticed that since ancient times Russian women preferred to give birth in a heated bath. It follows that the process of sweating facilitates and speeds up childbirth. The midwives who provided services during childbirth forced women in labor to actively move: walk to exhaustion, step over obstacles and anything, the main thing is not to lie down for a long time. This suggests the conclusion: such movements contribute to uterine contractions in a woman in labor.

If we trace the history of the Chinese, we can see that for many centuries they have preserved the tradition of giving birth in the sitting position of the woman giving birth. And in Holland, until recently, it was customary to give a childbirth chair as a dowry to the bride. nine0003

And in Holland, until recently, it was customary to give a childbirth chair as a dowry to the bride. nine0003

In our maternity hospital, we are actively implementing an alternative method of the birth process in the upright position of the woman in labor. Today, vertical births account for 60-65% of the total.

Being in an upright position, the expectant mother has the opportunity to observe the birth of her child herself. And the doctor and midwife are assigned only the role of direct observers of the natural course of childbirth.

And, most importantly, vertical childbirth does not require special equipment. So such childbirth implies complete freedom of active movements for the woman giving birth. She has the opportunity in the first stage of labor: to walk, stand, sit, rest in any position, take a warm shower and even swim. The basic principle of conducting the first stage of labor is that the woman in labor chooses a comfortable position for herself. nine0003

In the second stage of labor, a vertical position is taken during the passage of the fetal head in a wide part of the pelvic cavity. Tradition of a vertical position is possible in various poses: standing, sitting, half-sitting, squatting, kneeling or on a specially equipped chair. The optimal vertical posture is considered to be with a slight forward lean. During this position, a woman, kneeling, slightly leaning forward (by 20-30 degrees), is located on the usual "Rakhmanov" bed.

Tradition of a vertical position is possible in various poses: standing, sitting, half-sitting, squatting, kneeling or on a specially equipped chair. The optimal vertical posture is considered to be with a slight forward lean. During this position, a woman, kneeling, slightly leaning forward (by 20-30 degrees), is located on the usual "Rakhmanov" bed.

The difference between vertical births and classical ones is that the baby is born absolutely independently. Without any help from the traditional manual perineal protection aid, which is indispensable in conventional childbirth. Another plus of the vertical posture is that the mother has the opportunity, even before the end of the pulsation of the umbilical cord and the separation of the placenta, to take the newborn in her arms and attach it to her breast.

What is the biomechanism of childbirth in the vertical position of a woman with a certain inclination forward? nine0003

-

Thanks to this posture, the law of universal gravitation operates, in which the forces of natural gravity work.

Consequently, it is easier for the fetus to move through the birth canal with minimal energy consumption for itself.

Consequently, it is easier for the fetus to move through the birth canal with minimal energy consumption for itself. -

The vertical position for easy downward passage of the baby creates maximum pressure along the entire birth canal.

-

In a vertical position, the spinous processes of the vertebrae and the coccyx of the woman in labor deviate as much as possible back, while increasing the direct dimensions of the pelvic cavities. All this makes the unhindered progress of the child forward. nine0003

Such a simple tactic allows the perineum itself to slide slowly and smoothly, like a “stocking” from the fetal head. As a result, an accurate and careful birth of the baby's head occurs with the exclusion of traction for it at the birth of the shoulders. The body of the baby during such childbirth is born without hindrance. According to medical statistics, cases of birth injuries in newborns (even with a large mass) during childbirth in an upright position are 10 times less than in classical ones. nine0003

nine0003

Another advantage of "vertical" childbirth is the absence of deep injuries of the birth canal. And only small tears in the area of the labia and vaginal walls can be attributed to medium soft tissue injuries.

How to behave in childbirth? Learning to give birth quickly and with problems

Childbirth is a natural process, laid down by nature. The whole sequence of events that take place during this period is predetermined, but by your actions you can either speed up the birth of a baby, or complicate his birth. nine0003

Childbirth is the final and most important stage of pregnancy. How you behave and how accurately and skillfully you follow the instructions of the obstetrician depends on how you will feel and how quickly your baby will be born. What does a newborn need to know? Let's try to answer the most important questions.

1. When is it time to go to the maternity hospital?

Childbirth is a natural result of hormonal changes that occur in your body during the final stages of pregnancy. The sagging belly and heaviness in its lower part and the lumbar region speak of the imminent denouement of the story. Periodically, weak contractions occur, the stomach tenses and pulls down, but these sensations quickly pass, the uterus relaxes again and becomes soft. Such contractions are harbingers of childbirth, but they are far from real labor activity. nine0003

The sagging belly and heaviness in its lower part and the lumbar region speak of the imminent denouement of the story. Periodically, weak contractions occur, the stomach tenses and pulls down, but these sensations quickly pass, the uterus relaxes again and becomes soft. Such contractions are harbingers of childbirth, but they are far from real labor activity. nine0003

The signal to call an ambulance should be sufficiently strong contractions that are repeated at regular intervals, the appearance of mucous secretions from the genital tract, slightly stained with blood, or the outflow of amniotic fluid.

2. First stage of childbirth: we breathe for two!

From the moment the contractions become regular, the first stage of labor begins, during which the strength, frequency and duration of uterine spasms increases and the cervix opens. nine0003

During spastic contraction of the fibers of the uterine muscles, the blood vessels that carry arterial blood to the placenta and fetus are compressed. The fetus begins to experience a lack of oxygen, and this involuntarily makes you breathe deeper. The reflex increase in the rate of contractions of your heart will ensure the delivery of oxygen to the child. Nature has provided that these processes take place regardless of your consciousness, but you should not completely rely on it.

The fetus begins to experience a lack of oxygen, and this involuntarily makes you breathe deeper. The reflex increase in the rate of contractions of your heart will ensure the delivery of oxygen to the child. Nature has provided that these processes take place regardless of your consciousness, but you should not completely rely on it.

In the first stage of labor, during each contraction, you need to breathe calmly and deeply, trying not to hold your breath while inhaling. At the same time, the air should fill the upper sections of the lungs, as if raising the chest. You need to inhale through the nose, slowly and smoothly, exhale through the mouth, just as evenly. nine0003

3. Auto-training in the prenatal ward

To speed up the opening of the cervix, you need to walk more, but sitting is not recommended, while blood flow in the limbs is disturbed and venous blood stagnation occurs in the pelvis. From time to time it is useful to lie on your side, stroking your lower abdomen with both hands in the direction from the center to the sides, focusing on breathing and saying to yourself: "I am calm, I am in control of the situation, each contraction brings me closer to the birth of a baby. "

"

4. To relieve pain

Acupressure of the lower back can help relieve pain. Find the outer corners of the sacral rhombus on your lower back and massage these points with clenched fists.

Monitor the frequency and duration of contractions and if they weaken or sharply increase, immediately inform your doctor. In case of severe pain, you can ask for an anesthetic, but you should remember that you should not take the medicine too often, this is fraught with narcotic depression of the newborn and a decrease in his adaptive abilities. nine0003

If dilatation of the cervix has caused reflex vomiting, rinse your mouth with water and then drink a few sips to replenish lost fluid. Do not drink a lot, this can provoke a recurrence of vomiting.

5. The maternity ward is not a place for tantrums

They say that difficult childbirth is a person's retribution for walking upright. Childbirth is actually a painful process, but the presence of reason allows us, representatives of the genus Homo sapiens, to control our emotions. Screaming, crying, tantrums and swearing have no place in the maternity ward. This creates a tense environment, interferes with the normal course of childbirth, complicates diagnostic and therapeutic measures, and ultimately affects their outcome. nine0003

Screaming, crying, tantrums and swearing have no place in the maternity ward. This creates a tense environment, interferes with the normal course of childbirth, complicates diagnostic and therapeutic measures, and ultimately affects their outcome. nine0003

6. Second stage of labor - pushing and expulsion of the fetus

After the baby's head slips through the dilated cervix and ends up on the bottom of the pelvis, the pushing period of labor begins. At this time, there is a desire to push, as it usually happens during a bowel movement, but at the same time many times stronger. At first, the attempts are controllable, they can be "breathed", but by the beginning of the third stage of labor, the expulsion of the fetus, they become unbearable.

With the onset of the straining period, you will be transferred to the delivery room. Having settled down on the delivery table, rest your feet on the special steps, firmly grasp the handrails and wait for the midwife's command. nine0003

nine0003

While pushing, inhale deeply, close your mouth, clench your lips tightly, pull the handrails of the birthing table towards you and direct all the exhalation energy down, squeezing the fetus out of you. When the top of the baby appears from the genital slit, the midwife will ask you to ease your efforts. With gentle movements of her hands, she will first release the baby’s forehead, then his face and chin, after which she will ask you to push again. At the moment of the next attempt, the baby's shoulders and torso will be born. After the newborn is born, you can breathe freely and rest a little, but the birth is not over. nine0003

7. The third stage of labor and the final stage

The third stage of labor is the afterbirth period. At this time, weak contractions are observed, due to which the fetal membranes gradually exfoliate from the walls of the uterus.

About 10 minutes after your baby is born, your midwife will ask you to push again to deliver your afterbirth.