Forceps baby head

Forceps or vacuum delivery - NHS

Assisted delivery

An assisted birth (also known as an instrumental delivery) is when forceps or a ventouse suction cup are used to help deliver the baby.

Ventouse and forceps are safe and only used when necessary for you and your baby. Assisted delivery is less common in women who've had a spontaneous vaginal birth before.

What happens during a ventouse or forceps delivery?

Your obstetrician or midwife should discuss with you the reasons for having an assisted birth, the choice of instrument and how it will be carried out. Your consent will be needed before the procedure can be carried out.

Find out more about consent to treatment.

You'll usually have a local anaesthetic to numb your vagina and the skin between your vagina and anus (perineum) if you have not already had an epidural.

If your obstetrician has any concerns, you may be moved to an operating theatre so a caesarean section can be carried out if needed.

It is likely a cut (episiotomy) will be needed to make the vaginal opening bigger. Any tear or cut will be repaired with stitches. Depending on the circumstances, your baby can be delivered and placed on your tummy, and your birth partner may still be able to cut the cord if they want to.

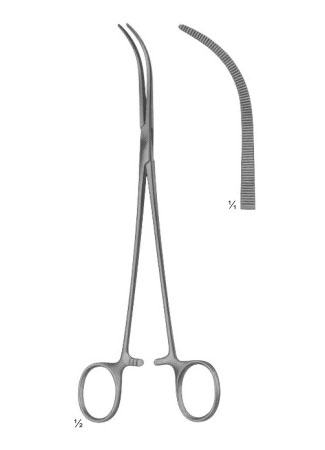

Ventouse

A ventouse (vacuum cup) is attached to the baby's head by suction. A soft or hard plastic or metal cup is attached by a tube to a suction device. The cup fits firmly on to your baby's head.

During a contraction and with the help of your pushing, the obstetrician or midwife gently pulls to help deliver your baby.

If you need an assisted birth and you are giving birth at less than 36 weeks pregnant, then forceps may be recommended over ventouse. This is because forceps are less likely to cause damage to your baby's head, which is softer at this point in your pregnancy.

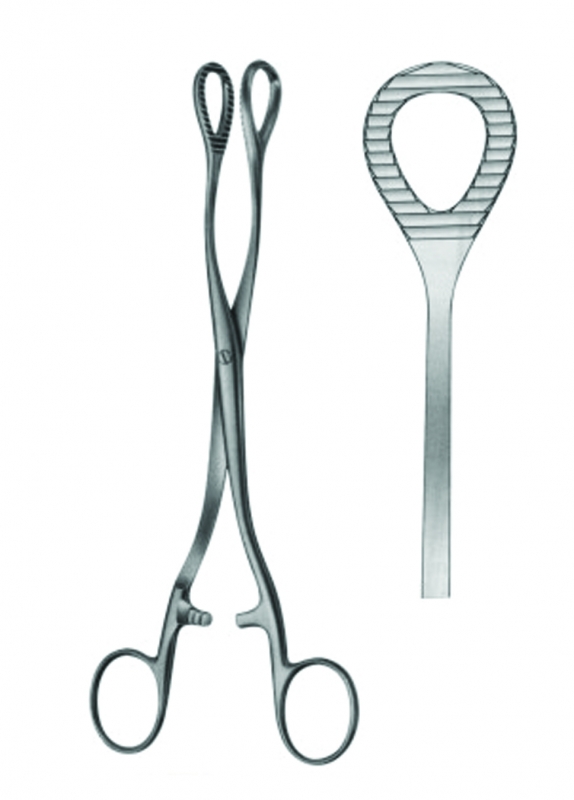

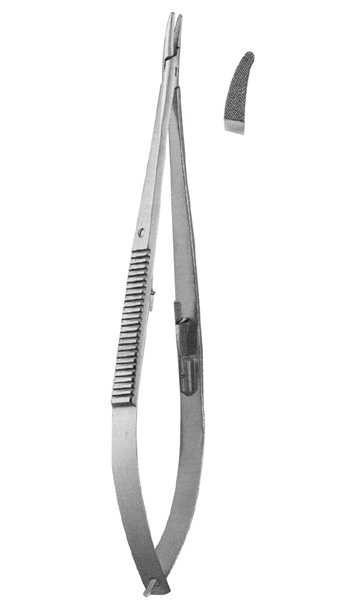

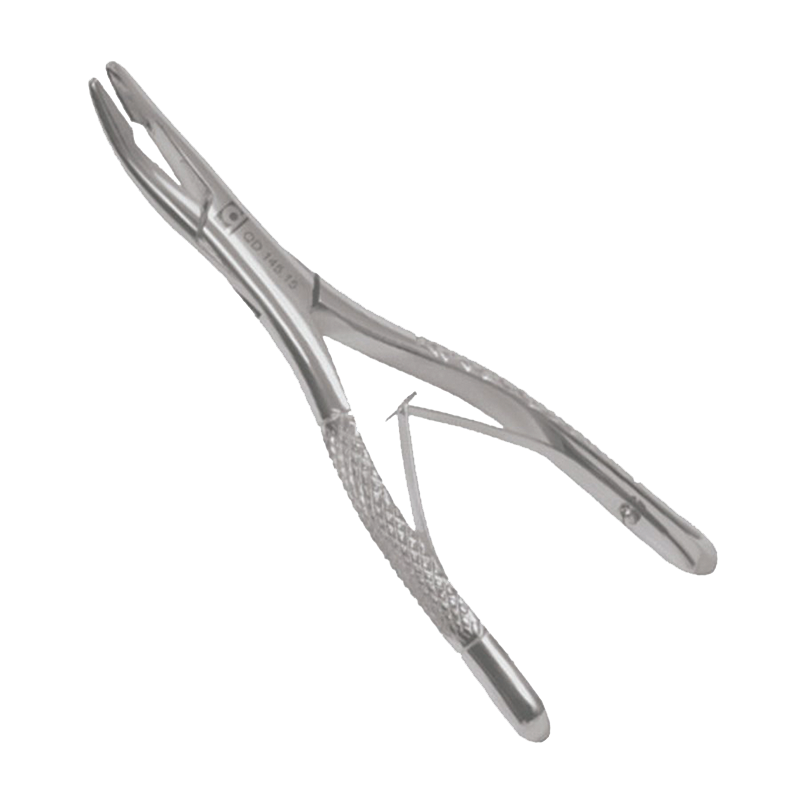

Forceps

Forceps are smooth metal instruments that look like large spoons or tongs. They're curved to fit around the baby's head. The forceps are carefully positioned around your baby's head and joined together at the handles.

They're curved to fit around the baby's head. The forceps are carefully positioned around your baby's head and joined together at the handles.

With a contraction and your pushing, an obstetrician gently pulls to help deliver your baby.

There are different types of forceps. Some are specifically designed to turn the baby to the right position to be born, such as if your baby is lying facing upwards (occipito-posterior position) or to one side (occipito-lateral position).

Why might I need ventouse or forceps?

An assisted delivery is used in about 1 in 8 births, and may be needed if:

- you have been advised not to try to push out your baby because of an underlying health condition (such as having very high blood pressure)

- there are concerns about your baby's heart rate

- your baby is in an awkward position

- your baby is getting tired and there are concerns that they may be in distress

- you're having a vaginal delivery of a premature baby – forceps can help protect your baby's head from your perineum

A children's doctor (paediatrician) is usually present to check your baby's condition after the birth. After the birth you may be given antibiotics through a drip to reduce your risk of getting an infection.

After the birth you may be given antibiotics through a drip to reduce your risk of getting an infection.

What are the risks of a ventouse or forceps birth?

Ventouse and forceps are safe ways to deliver a baby, but there are some risks that should be discussed with you.

Vaginal tearing or episiotomy

This will be repaired with dissolvable stitches.

3rd or 4th degree vaginal tear

There's a higher chance of having a vaginal tear that involves the muscle or wall of the anus or rectum, known as a 3rd- or 4th-degree tear.

This kind of tear affects:

- 3 in every 100 women having a vaginal birth

- 4 in every 100 women having a ventouse delivery

- 8 to 12 in every 100 women having a forceps delivery

Higher risk of blood clots

After an assisted birth, there's a higher chance of blood clots forming in the veins in your legs or pelvis. You can help prevent this by moving around as much as you can after the birth.

You may also be advised to wear special anti-clot stockings and have injections of heparin, which makes the blood less likely to clot.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence (leaking pee) is not unusual after childbirth. It's more common after a ventouse or forceps delivery. You should be offered physiotherapy to help prevent this happening, including advice on pelvic floor exercises.

Anal incontinence

Anal incontinence (involuntary farting or leaking poo) can happen after birth, particularly if there's been a 3rd or 4th degree tear. Because there's a higher risk of these tears happening with an assisted delivery, anal incontinence is more likely.

Are there any risks to the baby?

The risks to your baby include:

- a mark on your baby's head (chignon) being made by the ventouse cup – this usually disappears within 48 hours

- a bruise on your baby's head (cephalohaematoma) – this happens to around 1 to 12 of all 100 babies during a ventouse assisted delivery – the bruise is usually nothing to worry about and should disappear with time

- marks from forceps on your baby's face – these usually disappear within 48 hours

- small cuts on your baby's face or scalp – these affect 1 in 10 babies born using assisted delivery and heal quickly

- yellowing of your baby's skin and eyes – this is known as jaundice, and should pass in a few days

Afterwards

You'll sometimes need a small tube that drains your bladder (a catheter) for up to 24 hours.

You're more likely to need this if you've had an epidural as you may not have fully regained sensation in your bladder and therefore do not know when it's full.

The Royal College of Obstretricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) has further information about assisted delivery.

healthtalk.org has videos and written interviews of women talking about their experiences of vaginal birth, including forceps and ventouse.

Find out more about what happens in labour and pain relief in labour.

Video: what is involved in an assisted birth?

In this video, a midwife explains what an assisted birth is and what is involved.

Media last reviewed: 20 March 2020

Media review due: 20 March 2023

Page last reviewed: 9 June 2020

Next review due: 9 June 2023

What moms should know about forceps and vacuum deliveries | Your Pregnancy Matters

Imagine you are in labor and you’ve been pushing for hours. The doctor brings up the idea of using forceps or a vacuum to deliver your baby.

The doctor brings up the idea of using forceps or a vacuum to deliver your baby.

Did you imagine horror music and picture metal instruments attached to your baby’s head? If so, take a deep breath. It’s not that scary.

Operative vaginal delivery – which includes the use of forceps or vacuum – isn’t used very often anymore. From 2016-2019, 3% of births were delivered using forceps or vacuum. Meanwhile, approximately 32% percent of births in the same time period were delivered by cesarean section.

That one in three babies is delivered by C-section is a pretty startling concept, and some of those surgeries may have been avoided if physicians were more experienced in operative vaginal delivery. These methods – particularly forceps – are a dying art form. Few physicians coming out of training know how to use them or are comfortable using them.

But as we become more concerned with the rising C-section rate and related complications, there’s been an effort to revive physician training in the use of forceps and vacuum extraction. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists(ACOG) in recent years affirmed the use of forceps and vacuum as a way to safely avoid some C-sections.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists(ACOG) in recent years affirmed the use of forceps and vacuum as a way to safely avoid some C-sections.

The use of forceps or vacuum during delivery needs your consent. To help you avoid having to make a stressful decision during labor, let’s take a moment to learn more about when these methods might be beneficial.

How do forceps and vacuum work?

Forceps and vacuum extraction function in much the same way: they both guide the baby out of the birth canal during delivery. We do not really pull the baby out, but help direct the baby while you push – we still need your help! Before we perform an operative vaginal delivery, we make sure we know the position of the baby’s head, that your bladder is empty, and that you have adequate anesthesia on board.

Forceps look a little like oversized salad tongs. We gently slide one half along one side of the baby’s head, and repeat that on the other side, so the device cradles the baby’s face. During the next contraction, we’ll ask you to push and use the forceps to help guide the head out.

During the next contraction, we’ll ask you to push and use the forceps to help guide the head out.

The vacuum looks and acts like a suction cup. We place the cup on the baby’s head – not on the fontanel (or soft spot), but on a portion of the skull – and use a pump to create suction. Just like the forceps, we then use the vacuum to guide the baby’s head out as you push.

When might forceps and vacuum be used?

Operative vaginal delivery methods are used during the second stage of labor – after your cervix is completely dilated and you’ve been pushing. There are multiple reasons we might recommend the help of the forceps or vacuum, including:

- The baby just isn’t coming: For first-time moms or women who are making their first attempt at a vaginal delivery, we typically allow two hours to push if you don’t have an epidural, and three hours to push with an epidural, before we consider intervention. Women who have had children previously have one hour to push without an epidural, and two hours if they’ve had an epidural.

- Mom is exhausted: Labor is hard work, and the longer it goes on, the harder it is to keep up the effort. If a mother tells me, “I’m so tired. I can’t keep pushing,” she may just need a little assistance to finish the job.

- Baby’s heartbeat indicates a problem: If we become concerned about a change in your baby’s heart rate pattern on the fetal monitor, a quicker delivery may be needed.

- Mom’s health history: For a small number of women with certain medical conditions like some cardiac diseases, we may want to shorten the amount of time you need to push.

There may be times when using the forceps or vacuum would not be recommended, including when:

- We can’t accurately determine the position of the baby’s head.

- Your baby’s head has not moved down very far into the birth canal.

- Your baby has a condition that affects the strength of the bones or a bleeding disorder.

- We are concerned about the size of the baby not fitting through your pelvis.

And as an FYI, forceps or vacuum also may be used during breech deliveries or C-sections to help deliver the baby.

What are the benefits and risks of using forceps and vacuum?

The main advantage to trying an operative vaginal delivery is it could save you from having major surgery that you may not need. A second stage C-section is more difficult and complex than when it is performed earlier in the labor process. The baby’s head, which is now wedged in the birth canal, may first need to be pushed up so the baby can be delivered through the incision in the uterus. Second stage C-sections also come with higher risks of bleeding and infection.

Sometimes a baby’s head is not positioned so it’s coming straight out, but instead is cocked to the side, making it more difficult to pass through the birth canal. We may be able to correct the head position with the forceps. It’s amazing how some simple maneuvers can correct the position of the head; some moms can even push from that point forward without the assistance of the forceps.

Using an operative vaginal delivery method also may result in a faster delivery for your baby than a C-section, which at times is really important. Women can give birth within minutes with the use of forceps or a vacuum delivery, but with a C-section, a woman will need to be taken to an operating room, positioned on an OR table, and have adequate anesthesia in place before undergoing the surgery.

Although rare, there are risks associated with these delivery methods. Possible risks to the mother include:

- Increased potential of lacerations (tearing around the vagina, rectum, or urethra)

- Short-term urinary incontinence

- Increased blood loss

Possible risks to the baby include:

- Minor facial injuries including bruising

- Temporary facial muscle weakness

- Skull fracture (but realize that this can also happen with delivery via a C-section when the head is already low in the pelvis)

- Bleeding

What questions should you ask your physician?

I recommend discussing operative vaginal delivery methods with your physician during your prenatal care, so you have all the information you need before you’re asked to make a decision in the heat of the moment.

Ask your physician how comfortable they are in using the forceps or vacuum. For instance, I am very experienced in using forceps, but I do not have training or expertise in using a vacuum extractor. Some physicians prefer one over another, and some prefer to go straight to a C-section. These are procedures in which the skill of the physician matters, and it’s important they not attempt it if they can’t do it.

While making a birth plan, you can learn about your delivery options and let your physician know what you are comfortable with. I have patients who desperately do not want a C-section, and while I tell them that we will do everything we can, sometimes events dictate that we can’t safely use the forceps or vacuum to deliver vaginally. I am always a little sad when someone’s baby is too high in the birth canal to even attempt using forceps and I have to resort to cesarean delivery. But the safety of the baby and mother is our top priority. I also have patients who tell me they prefer to not use forceps or vacuum. In those cases, I tell them that I also prefer to not have to use these methods, but I explain the situations in which they may be beneficial.

In those cases, I tell them that I also prefer to not have to use these methods, but I explain the situations in which they may be beneficial.

You need to have accurate information to weigh the risks of a possible operative vaginal delivery so you can make a decision that is best for you and for your baby. Talk to your physician about each option well before you are in labor.

If you have questions about delivery options, call 214-645-8300 or request an appointment online with one of our Ob/Gyns.

Vaginal delivery with forceps and vacuum. Dangerous?

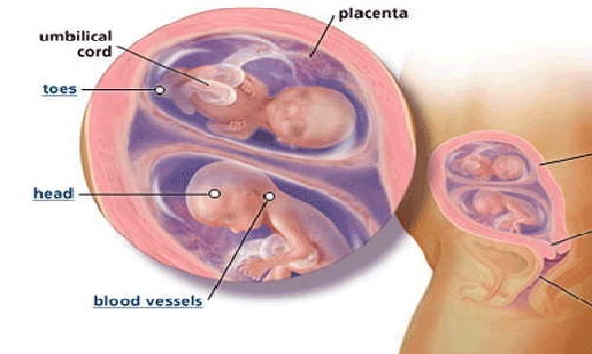

Usually during natural childbirth, your baby goes out into this world on his own. But babies are not always in a hurry to be born according to the plan, in such cases, a little help may be required to transfer the baby to mother's hands. The doctor uses certain methods to deliver the baby, which we will discuss in this article.

Vaginal delivery

Assisting and stimulating vaginal delivery is essential when the natural birth process does not move forward. In these cases, the medical team will use certain devices, such as forceps and a vacuum extractor, to safely reach the child.

These methods are usually used when there is a prolonged labor with more than 2-3 hours of unsuccessful efforts by the woman. Instruments may also become necessary when the doctor sees that the child's heart rate is dropping. These methods are not used until the cervix is fully dilated with the baby's head no more than 5 centimeters above the vaginal opening.

Use of forceps

Forceps are a metal device that is used to grasp the baby's head through the birth canal during prolonged labor. Tongs are like long spoons or tongs. Forceps are also used if the baby's condition worsens or if the position is incorrect. Forceps may be used when the doctor sees that the baby's face is in the wrong direction or is not moving down the birth canal. The reason for this may be uterine atony, which means that the uterus is not contracting enough. Before you get the baby with forceps, anesthesia is done in the area around the vagina. In addition, the doctor will perform an episiotomy (an incision between the vagina and anus) prior to delivery.

Forceps may be used when the doctor sees that the baby's face is in the wrong direction or is not moving down the birth canal. The reason for this may be uterine atony, which means that the uterus is not contracting enough. Before you get the baby with forceps, anesthesia is done in the area around the vagina. In addition, the doctor will perform an episiotomy (an incision between the vagina and anus) prior to delivery.

Benefits of using forceps

Forceps have higher success rates compared to vacuums, according to the health organization. Trained doctors who have been practicing for many years would prefer to use forceps as the ideal approach to childbirth. Second, the use of forceps poses a lower risk of developing a cephalematoma versus a vacuum extractor. A cephalematoma is a condition in which blood accumulates in the area between the bones of the skull and the tissues of the child's head.

Disadvantages of using forceps

The use of forceps increases the chance of vaginal tears compared to a vacuum extractor. The perineum is recovering, but this takes time. Forceps-assisted births are also associated with a risk of damage to the facial nerve. Although these complications are rare, they are more common as a result of the use of forceps.

The perineum is recovering, but this takes time. Forceps-assisted births are also associated with a risk of damage to the facial nerve. Although these complications are rare, they are more common as a result of the use of forceps.

Vacuum Birth Extractor

Doctors can also use an instrument called a vacuum extractor. The doctor attaches the cup-shaped extractor to the top of the child's head and directs him to the birth canal. The device pulls the baby's head and does not let him go back into the birth canal.

Vacuum extractor advantage

The vacuum extractor has become more commonly used because the method requires less anesthesia and pain medication compared to forceps, thus less risk.

Disadvantages of using a vacuum extractor in

Although the vacuum extractor poses less of a risk, slipping off the top of the instrument makes a caesarean section unavoidable. This increases the chances of complications for both mother and baby. The vacuum extractor can also contribute to other complications such as retinal bleeding, a condition in which bleeding occurs in the blood vessels of a child's retina. The vacuum extractor also poses a risk of developing a cephalematoma. All of these complications can occur due to trauma during childbirth. In some cases, vacuum extraction can result in swelling or bruising of the baby's scalp.

This increases the chances of complications for both mother and baby. The vacuum extractor can also contribute to other complications such as retinal bleeding, a condition in which bleeding occurs in the blood vessels of a child's retina. The vacuum extractor also poses a risk of developing a cephalematoma. All of these complications can occur due to trauma during childbirth. In some cases, vacuum extraction can result in swelling or bruising of the baby's scalp.

Physicians should be well versed in the specific cases where these methods are applied. If you have any doubts, worries, questions about the use of forceps and a vacuum extractor, be sure to ask your gynecologist. You should be aware of the risks that arise when using these tools!!!

Obstetrical practices that have crippled babies and mothers in the past

- Photo

- Image Source/Charles Gullung RM/Legion

OB/GYN

Among the techniques used by obstetricians in the past, expectant mothers hear two: forceps and vacuum extraction.

Obstetric forceps is a spoon-like metal instrument. They are applied on both sides to the baby's head, or rather, on the ears and the area surrounding them. This procedure requires great skill and experience from the obstetrician: if the spoons are not on the sides of the skull, they can damage the eyes or the back of the head of a small one. Having installed the spoons, the doctor gently pulls the baby's head closer to the exit, and as soon as she is born, he immediately removes them, and then the child chooses himself.

Vacuum Extractor is a soft suction cup connected to a vacuum pump. It is attached to the baby's head and wraps around it quite tightly. As in the case of forceps, the doctor helps the baby with gentle sips, and as soon as the little head is born, he removes the tool.

Obstetrical forceps and a vacuum extractor were used by doctors in the following cases:

-

the baby does not have enough oxygen and needs to be taken out as soon as possible;

-

his mother's efforts remain too weak even after medication;

-

correctly positioned placenta exfoliates prematurely;

-

The well-being of the expectant mother is deteriorating rapidly for some reason.

But both of these methods are fraught with complications for both mother and her baby. If in a woman they can cause trauma of the soft birth canal and bleeding , then in a child - traumatic brain injury and hemorrhage in the brain and cranial cavity .

If in the 1970s–1980s obstetric forceps and a vacuum extractor were used quite often, now in Russian clinics this happens only in 0.6% of cases.

What is the current alternative to forceps and vacuum extractors? Obstetricians perform an emergency caesarean section on women in labor. Nowadays, this operation has become safer, and the advent of new, non-inflammatory suture material and modern antibiotics that prevent complications have made it a successful alternative to many other interventions. Therefore, obstetricians today generally opt for a more predictable option.

The main task of modern obstetricians is to make childbirth as safe as possible for the child and his mother. So, to exclude everything that may pose at least some risk: unsafe manipulations, traumatic instruments, drugs with side effects.

So, to exclude everything that may pose at least some risk: unsafe manipulations, traumatic instruments, drugs with side effects.

- Photo

- Image Source/Charles Gullung RM/Legion

Imagine a common situation: a woman's cervix dilates too slowly. About 30 years ago, doctors would have opened it themselves: either with their hands or with the help of a meter rinter device - a rubber balloon that was inserted into the cervical canal, filled with saline, and a load was hung from the outside. The contractions intensified, and the cervix opened up, but in addition to being very painful for a woman, such an intervention also increased the risk of problems. A damaged fetal bladder is a gateway for infection, besides, the umbilical cord could fall out into the opened “exit”, and the outcome of childbirth became unpredictable. How do obstetricians work today if the cervix opens slowly or does not open at all?

-

First of all, the expectant mother is given pain relief, usually epidural anesthesia .

After all, long painful contractions increase muscle spasm, and the cervix shrinks even more. Pain relief not only relieves discomfort, but also relaxes the muscles, and the neck gradually opens.

After all, long painful contractions increase muscle spasm, and the cervix shrinks even more. Pain relief not only relieves discomfort, but also relaxes the muscles, and the neck gradually opens. -

A woman is injected with hormones prostaglandins - these are natural participants in the process of childbirth, which help it to develop more actively.

-

Place kelp sticks into the cervix. They gradually swell inside the body, slowly and carefully expanding the "exit".

-

If the above methods do not work, and the amniotic sac is already damaged, doctors will not wait longer than 4-6 hours for the cervix to dilate and will perform a caesarean section . A long wait is fraught with the development of infection, and a lack of oxygen for the child.

Yesterday…

-

with a weak opening of the cervix, it was dilated with fingers or a meter;

-

when the child was in a transverse position, the so-called “turn on the leg” was made;

-

twins and premature babies were more likely to be born vaginally with a risk of complications;

-

if a woman could not push because of cardiovascular disease, myopia or other problems, forceps were applied to her.

Today…

Another situation that clearly shows how obstetric methods have changed is the transverse position of the child. This is the position of the baby, in which his head and legs are on the sides of the uterus. If a large child was expected, the woman was given a caesarean section, but if the baby was of medium size, the old obstetricians often acted differently. The doctors waited for the full disclosure of the cervix, injected the expectant mother with anesthesia, opened the fetal bladder and removed the baby with their hands.

Due to the fact that caesarean sections have become much safer in recent decades, there have been many more cases when a woman after the first caesarean section becomes a mother for the second and third time. It also happens that younger children are born naturally without any problems - for example, if the reason for the first caesarean section was not related to the mother, but to the baby.

This manipulation was called "turning on the leg": the baby was grabbed by the leg, turned to the exit and pulled out first one leg, then the other, then the torso, arms, shoulders, head.