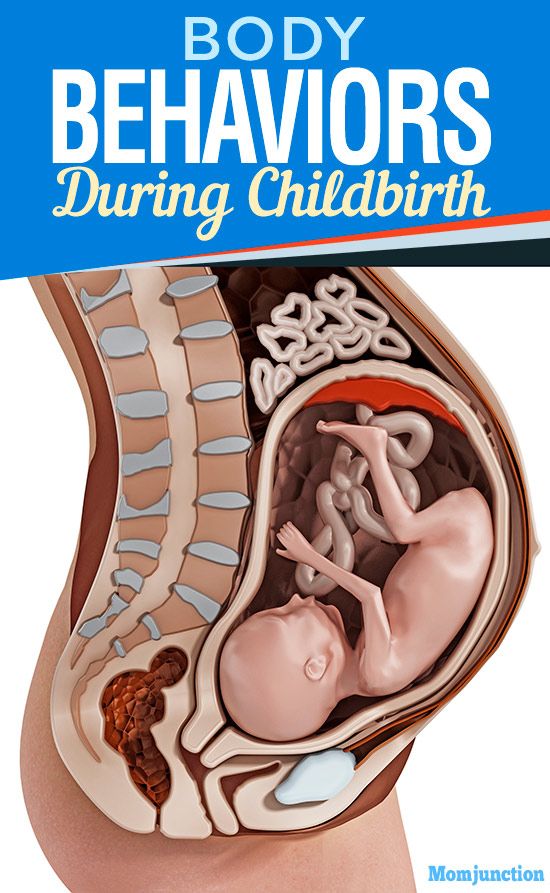

Does your pelvis break during childbirth

Traumatic Pelvic Ring Injury following Childbirth with Complete Pubic Symphysis Diastasis

On this page

AbstractIntroductionCase ReportLiterature ReviewDiscussionConflicts of InterestReferencesCopyrightRelated Articles

Case. Traumatic pelvic ring injury following childbirth is a rare but debilitating condition. We present a case of a 28-year-old female who sustained a traumatic pelvic ring injury following childbirth with a complete pubic symphysis separation of 5.6 cm treated successfully with nonoperative management. Conclusion. Operative and nonoperative treatments for traumatic pelvic ring injuries following childbirth have been described without universal adoption of a uniform treatment modality. We hope this case study adds to the collection of data to help guide medical decision-making in the future as surgeons encounter patients with similar orthopedic injuries.

1. Introduction

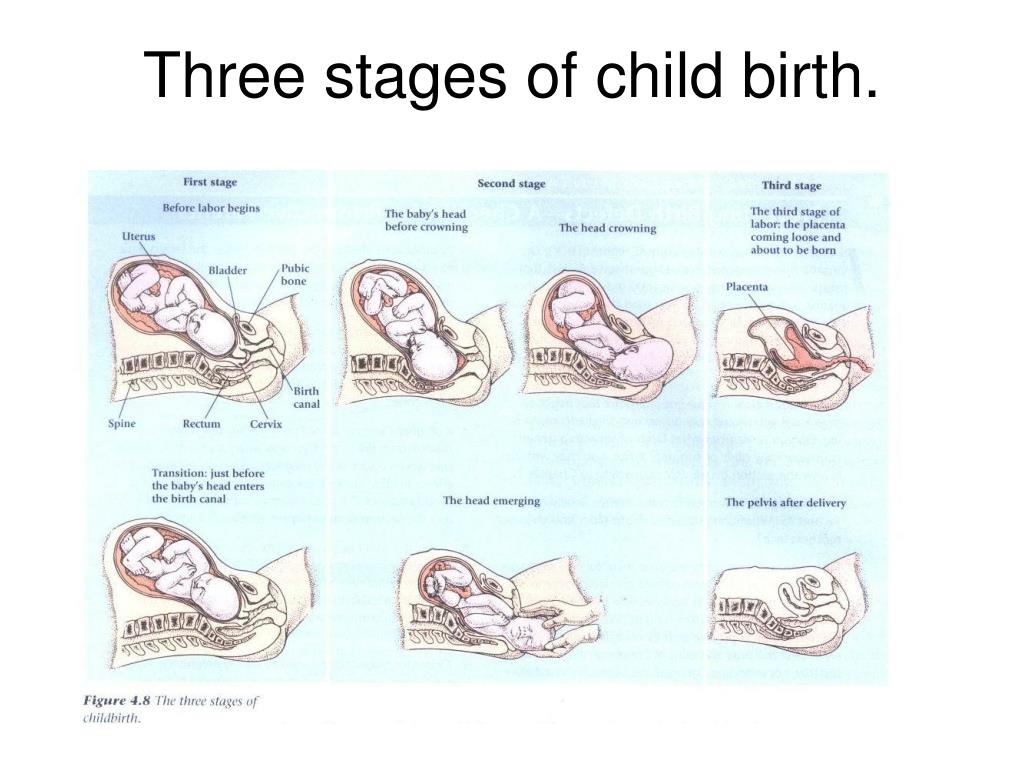

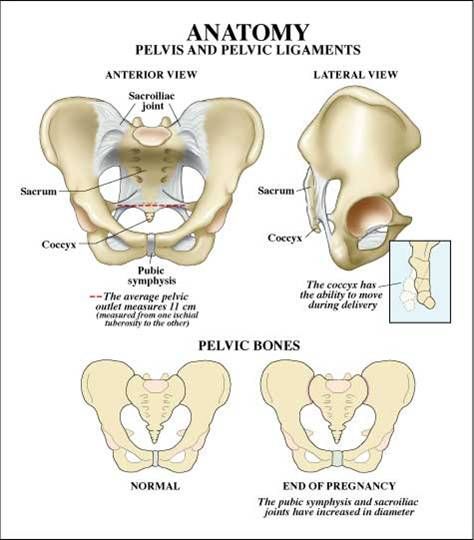

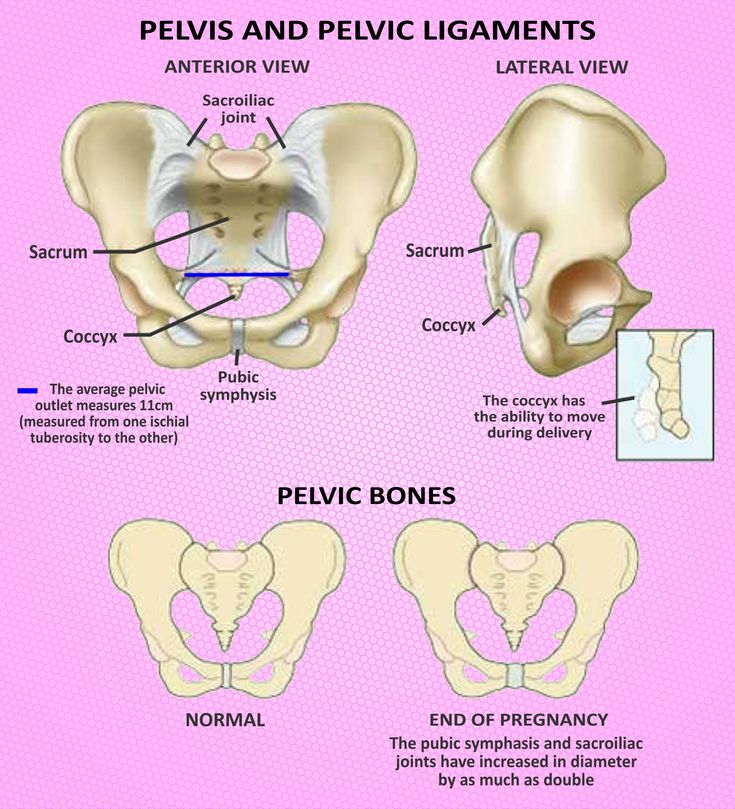

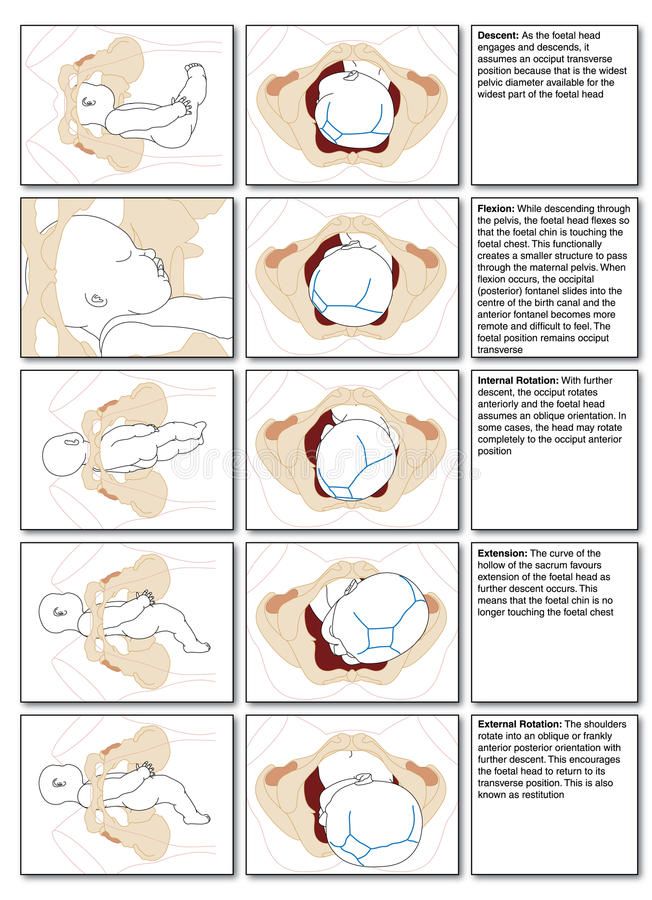

Traumatic pelvic ring injury with complete pubic symphysis diastasis following childbirth via vaginal delivery is a rare but debilitating condition. Widening of the cartilaginous joint during pregnancy prior to childbirth is physiologic and assists in widening the birth canal for successful delivery [1]. However, reports of nonphysiologic pubic diastasis exceeding that required for childbirth (typically greater than 1 cm) can leave mothers with debility and extreme pain. Incidence of complete separation of the pubic symphysis is reported to be within 1 in 300 to 1 : 30,000, with many instances likely undiagnosed [1, 2]. The orthopedic surgeon is presented with a difficult decision when managing these injuries as women are high-risk surgical candidates in the peripregnancy state, and prolonged debility can affect care for their newborn. We present the following case report of a 28-year-old female who sustained a traumatic pelvic ring injury with complete pubic diastasis of 5.6 cm that was successfully treated with nonoperative management, returning to full function one year out from injury. We present this case report in hopes to provide information to orthopedic surgeons presented with this challenging and debilitating diagnosis.

2. Statement of Informed Consent

Our patient was informed that data pertaining to her case and treatment would be submitted for publication and she agreed.

3. Case Report

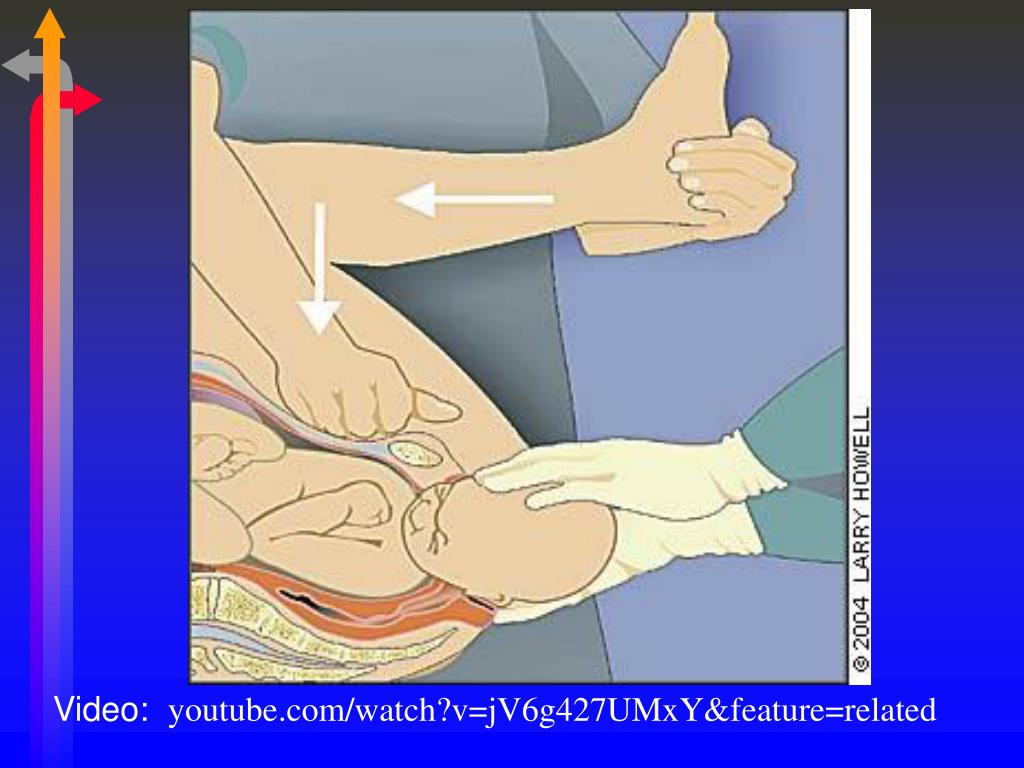

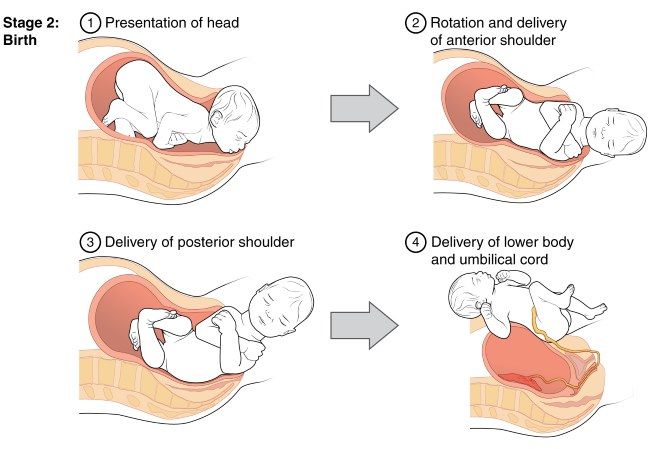

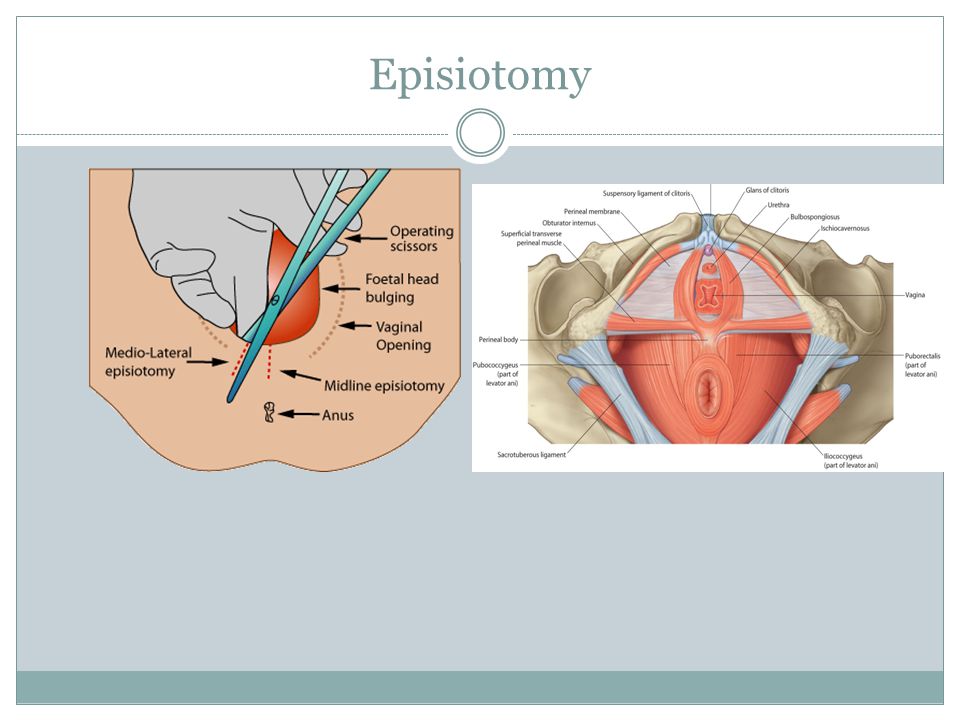

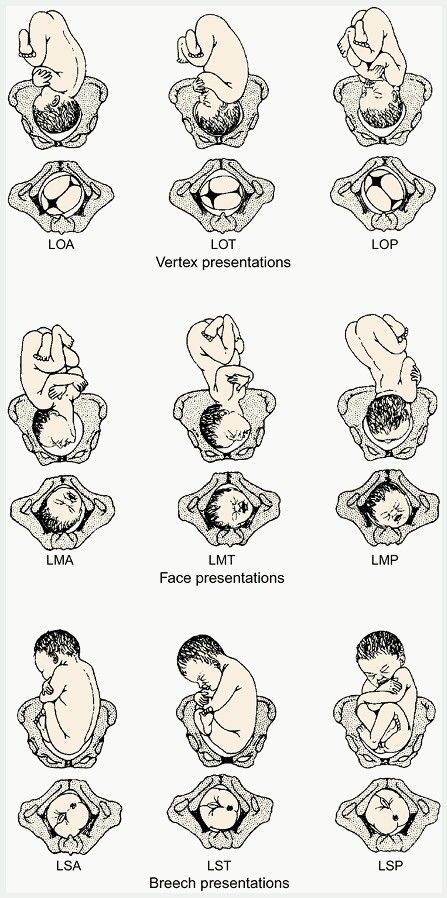

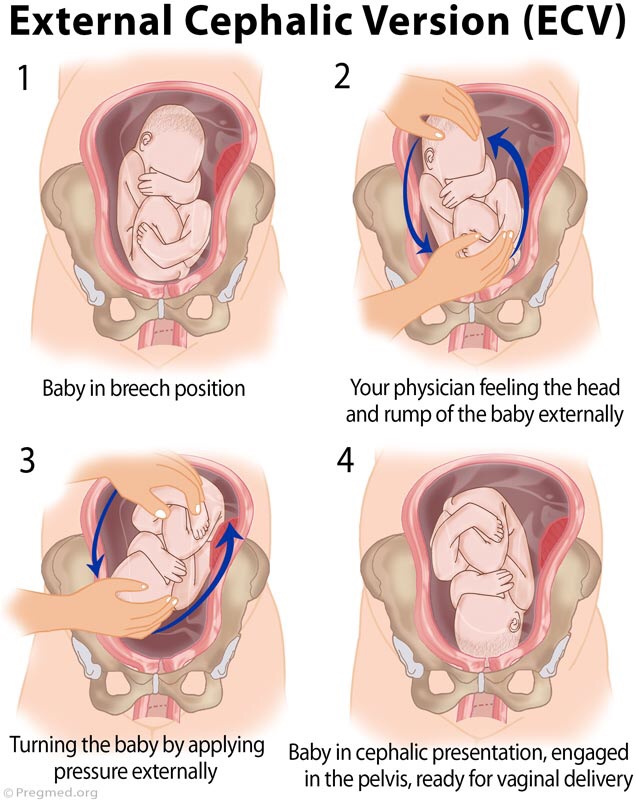

Our patient is a 28-year-old G2PO female who presented to our institution in labor for the birth of her first child. At time of presentation, the position of the baby was cephalic. The patient denies antecedent pelvic pain or difficulty with ambulation prior to delivery. Active labor was initiated with Pitocin augmentation. She was provided an epidural spinal anesthesia. Following 3 hours of pushing, the patient delivered a baby boy of 6 lb 11.2 oz (3040 grams). The patient did sustain a grade 1 peroneal tear which was closed primarily with suture.

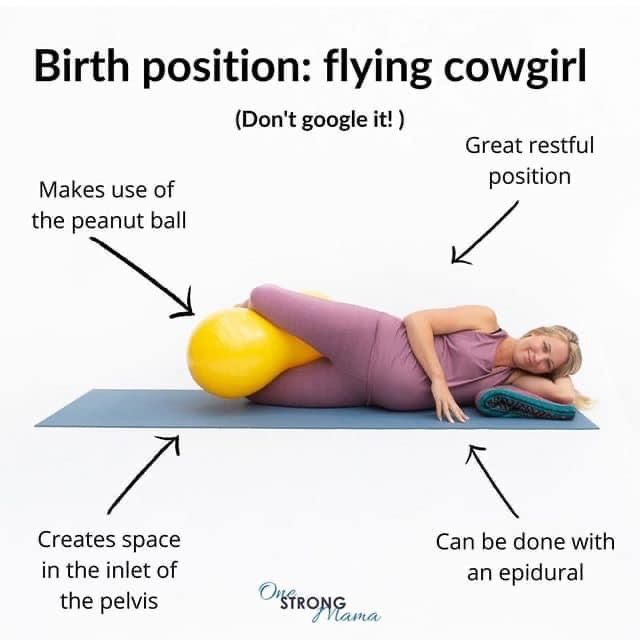

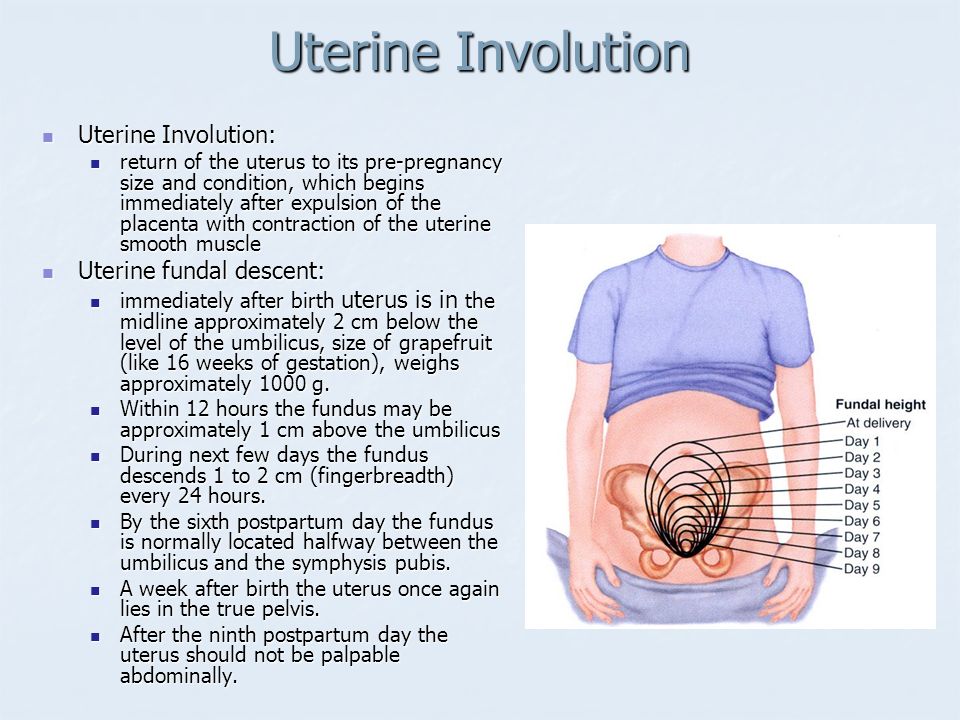

Two hours following delivery, the patient was evaluated by her obstetrics physician for persistent and worsening anterior pelvic pain and low back pain with inability to ambulate. She was then evaluated with an AP radiograph of the pelvis which revealed a complete pubic symphysis diastasis of 5. 6 cm with widening of bilateral sacroiliac joints posteriorly (Figure 1) which is redemonstrated with 3D CT reconstruction (Figure 2). That evening, the orthopedic surgery team was asked to evaluate the patient. Following evaluation, a generic pelvic binder was placed on the patient and repeat imaging showed no significant improvement in her diastasis nor did the patient experience a reduction in her pain. The patient was left in a pelvic binder with constant skin assessments and was allowed to weight bear as tolerated. Considerations were given for both operative open reduction with anterior internal plate fixation and continued nonoperative management; however, the patient and family elected to continue nonoperative management with close observation.

6 cm with widening of bilateral sacroiliac joints posteriorly (Figure 1) which is redemonstrated with 3D CT reconstruction (Figure 2). That evening, the orthopedic surgery team was asked to evaluate the patient. Following evaluation, a generic pelvic binder was placed on the patient and repeat imaging showed no significant improvement in her diastasis nor did the patient experience a reduction in her pain. The patient was left in a pelvic binder with constant skin assessments and was allowed to weight bear as tolerated. Considerations were given for both operative open reduction with anterior internal plate fixation and continued nonoperative management; however, the patient and family elected to continue nonoperative management with close observation.

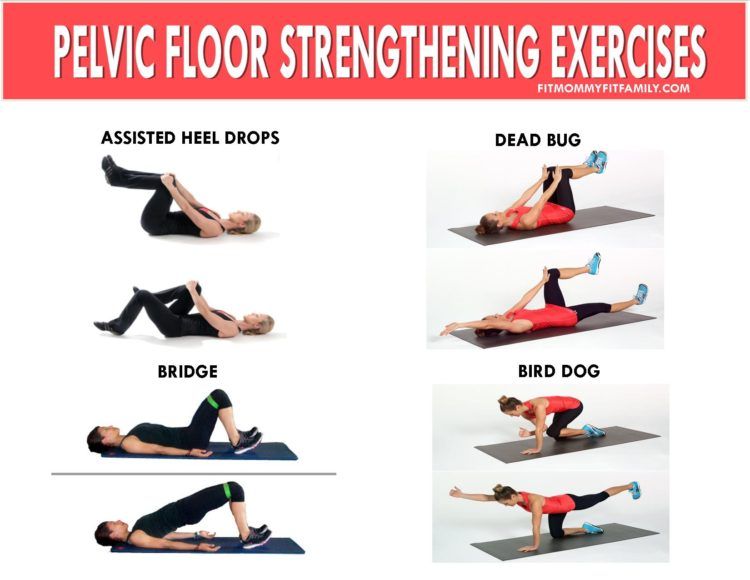

The patient was transferred to the orthopedic surgery floor of our institution the following day where she worked with physical therapy twice daily for assistance with mobilization, beginning the following day post diagnosis. The patient had persistent pelvic pain and difficulty ambulating. On hospital day 8, as patient was only able to sit on the side of the bed and ambulate several feet with the assistance of a walker device, she was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation where she spent 15 days before being discharged home able to walk with minimal pain with assistance of the walker device. The patient was seen back in office for her first clinic follow-up 6 weeks following her delivery. At that time, the patient’s AP pelvic X-ray revealed 2.0 cm of residual pubic diastasis (Figure 3), and the patient was using an occasional walker when on uneven ground but able to do stairs and perform ADLs. She continued to work with outpatient physical therapy for a total of 6 months before returning to full-time work. At her 1-year follow-up, she is back to full-time work, ambulates both inside and outside the home without assistance, and is able to do stairs, perform ADLs, and care for her baby with only mild intermittent low back pain managed by over-the-counter anti-inflammatories.

On hospital day 8, as patient was only able to sit on the side of the bed and ambulate several feet with the assistance of a walker device, she was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation where she spent 15 days before being discharged home able to walk with minimal pain with assistance of the walker device. The patient was seen back in office for her first clinic follow-up 6 weeks following her delivery. At that time, the patient’s AP pelvic X-ray revealed 2.0 cm of residual pubic diastasis (Figure 3), and the patient was using an occasional walker when on uneven ground but able to do stairs and perform ADLs. She continued to work with outpatient physical therapy for a total of 6 months before returning to full-time work. At her 1-year follow-up, she is back to full-time work, ambulates both inside and outside the home without assistance, and is able to do stairs, perform ADLs, and care for her baby with only mild intermittent low back pain managed by over-the-counter anti-inflammatories.

4. Literature Review

There is currently much debate over the appropriate treatment modality for postpartum pubic symphysis diastasis. Kharrazi et al. described four patients with an average pubic symphysis diastasis of 6.4 cm all treated nonoperatively with a pelvic binder. These patients had a reduction of their diastasis to 1.7 cm; however, all four had persistent sacroiliac joint pain. They suggest considering operative treatment at a diastasis of >4 cm. Dunivan described the use of an external fixator successfully on a woman with a 6.2 cm diastasis with the ability to weight bear on her second post-op day and discharged on postpartum day four, able to ambulate with a walker.

Cases of open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of pubic symphysis diastasis have also been described in the literature. Najibi et al. describe ten patients treated operatively with internal fixation [3]. Three patients had an excellent outcome, four had a good result, and three had a fair or poor result. Rommens described the successful internal fixation of three patients with diastasis ranging from 15 mm to 45 mm who failed conservative management. Yoo et al. identified that primigravid females had a higher risk for diastasis.

Rommens described the successful internal fixation of three patients with diastasis ranging from 15 mm to 45 mm who failed conservative management. Yoo et al. identified that primigravid females had a higher risk for diastasis.

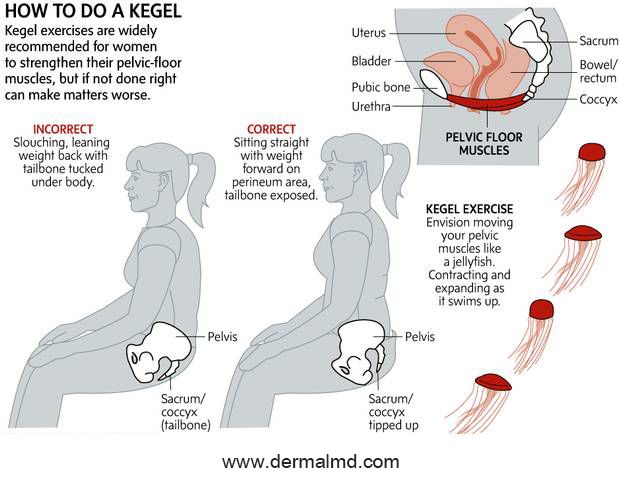

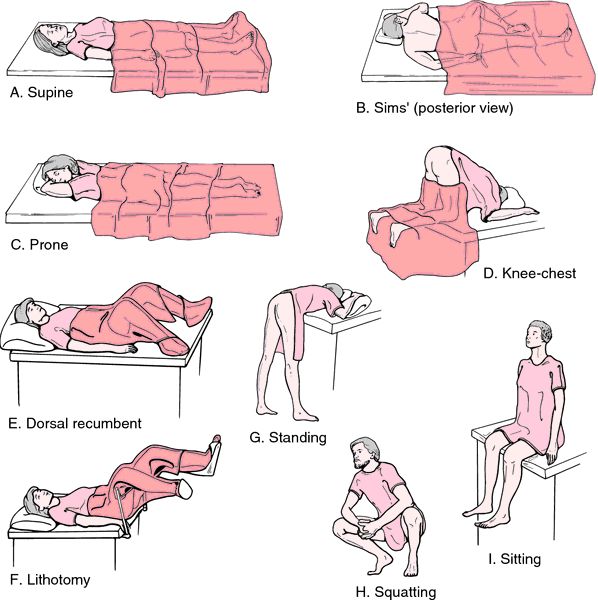

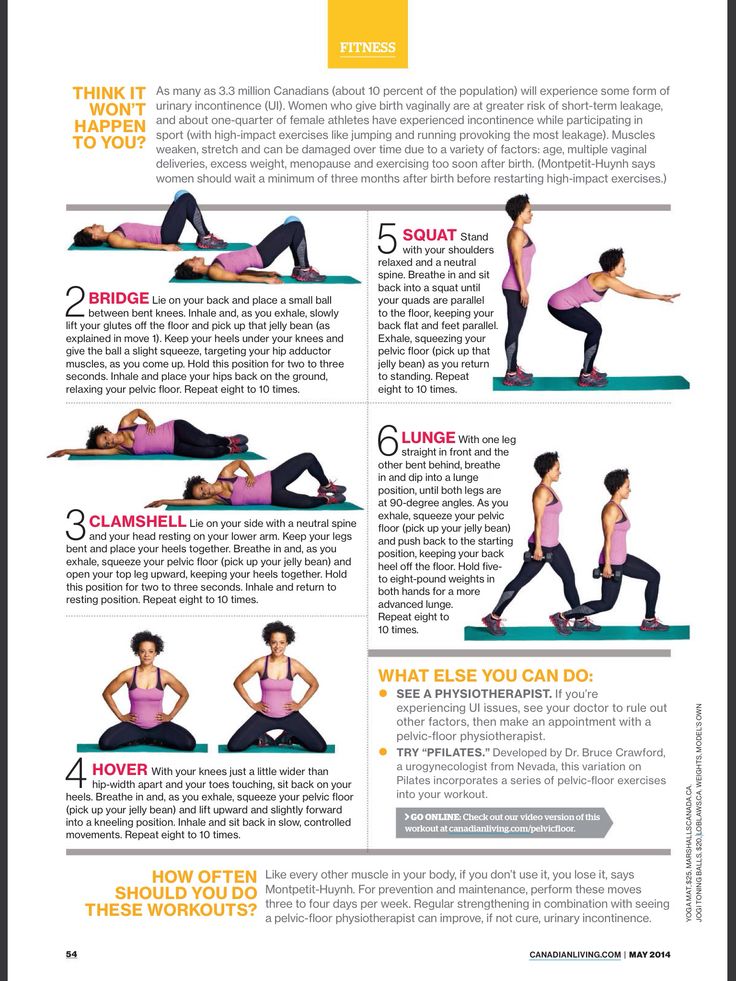

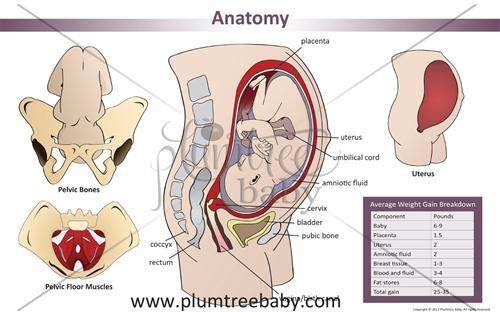

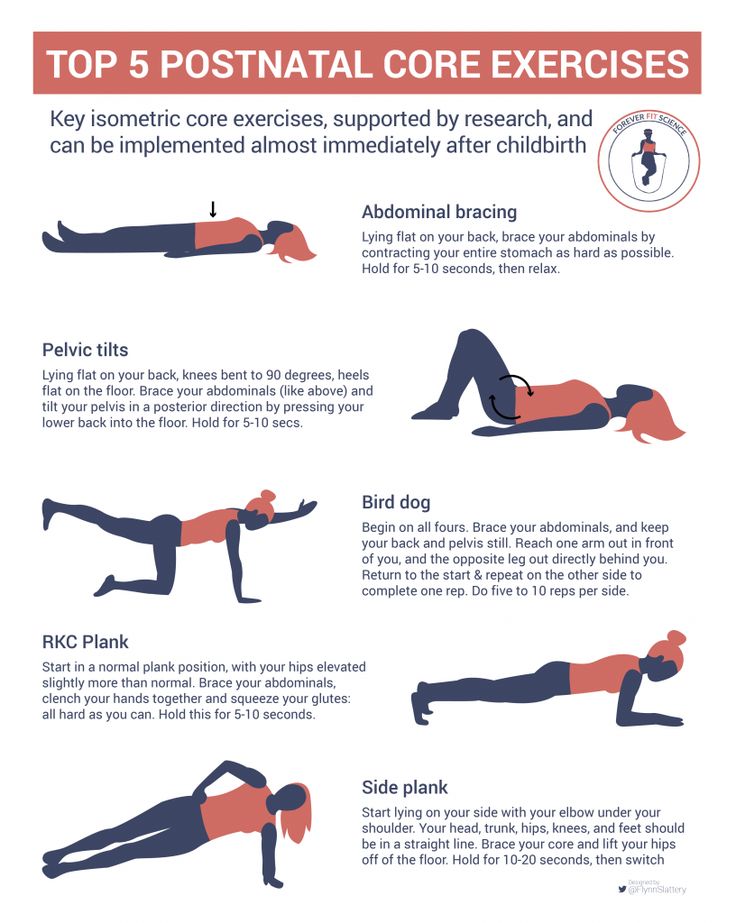

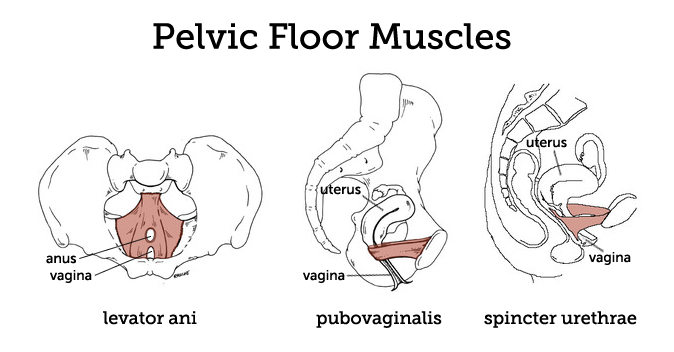

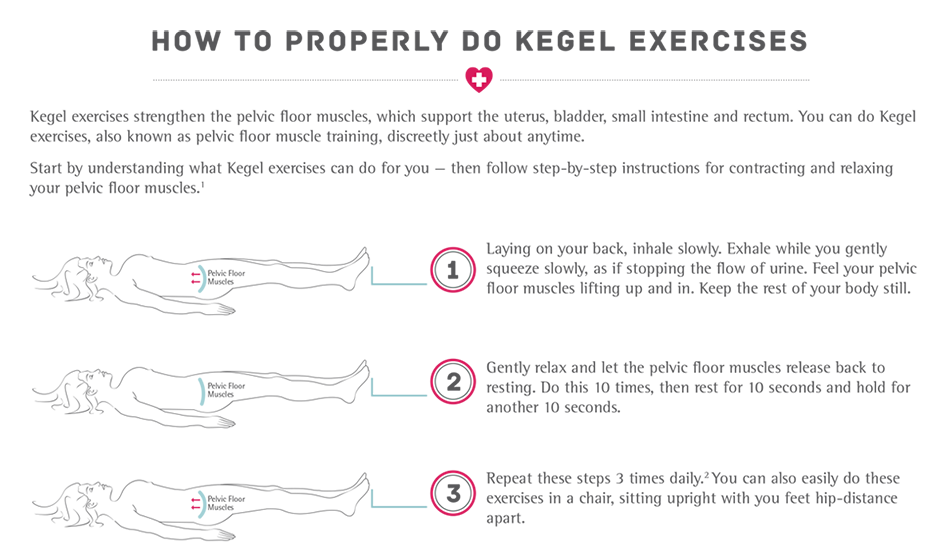

Physical therapy for the management of pubic symphysis diastasis has been well documented. Stretch and often complete rupture of both the superior and inferior pubic ligaments result in separation of the symphysis. Strengthening of the surrounding soft tissue, including the rectus abdominis, thoracolumbar musculature and fascia, and quadriceps and hamstrings, helps stabilize and reduce stress through the pubic symphysis [4]. A stable symphysis without recurrent stress through the joint allows a slow return towards anatomic position with scarring of the torn ligaments back towards their attachments. A combination of closed chain exercises targeting these muscle groups along with altered sleep positioning (pillow between legs during slumber) are recommended to expedite the healing process [5].

5. Discussion

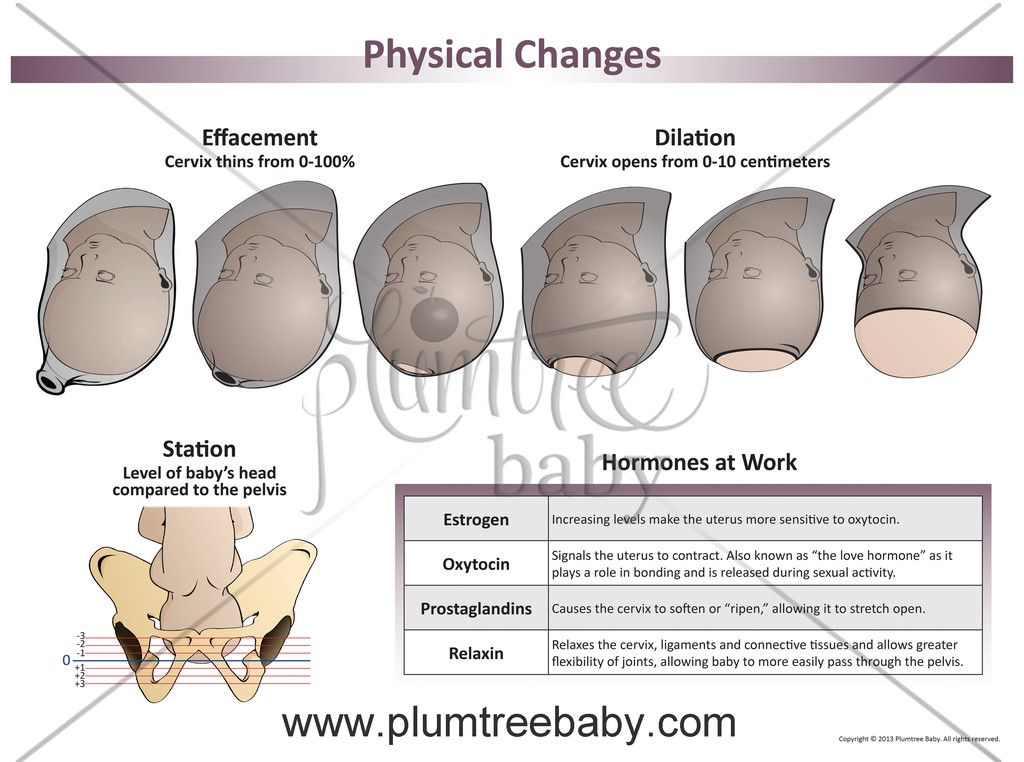

Widening of the pubic symphysis during childbirth is physiologic and is an advantageous adaptation in widening of the birth canal for delivery. However, excessive widening of the pubic symphysis can be pathologic and lead to debilitating pain. A separation of more than 1 cm postpartum is historically noted to be pathologic and symptomatic [1]. Furthermore, literature suggests consideration of operative treatment for separations greater than 4 cm [6]. Relaxin, a hormone secreted by the placenta during pregnancy, peaks during the first trimester and again peripartum. A modulator of arterial compliance and cardiac output during pregnancy, relaxin also serves to relax the pelvic ligaments and contributes to softening of the cartilage of the pubic symphysis for preparation of the birth canal for delivery [7, 8]. Identified risk factors for postpartum pubic symphysis diastasis include primigravid women, multiple gestations, and prolonged active labor [2]. When considering operative management of postpartum symphysis diastasis, it is important to consider and respect the physiologic changes of pregnancy that could complicate surgery. Pregnancy and peripartum bed rest are associated with an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis [2]. In addition, pelvic anatomy can be distorted following birth and elevated relaxin levels have also been shown to be associated with increased uterine bleeding, which complicate surgical treatment [2, 9]. Treatments described for pelvis diastasis include nonoperative treatment with application of pelvic binder coupled with physical therapy and immediate weight bearing, non-weight bearing with bedrest, closed reduction with application of binder, application of anterior external fixator with or without sacroiliac screw fixation, and anterior internal fixation with plate and screws. While our patient initially presented with a diastasis of 5.63 cm, we pursued nonoperative management with application of a pelvic binder and immediate physical therapy with unrestricted weight bearing. At 6-week follow-up, repeat imaging showed improvement of diastasis to 2.0 cm with significant improvement in symptoms.

Pregnancy and peripartum bed rest are associated with an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis [2]. In addition, pelvic anatomy can be distorted following birth and elevated relaxin levels have also been shown to be associated with increased uterine bleeding, which complicate surgical treatment [2, 9]. Treatments described for pelvis diastasis include nonoperative treatment with application of pelvic binder coupled with physical therapy and immediate weight bearing, non-weight bearing with bedrest, closed reduction with application of binder, application of anterior external fixator with or without sacroiliac screw fixation, and anterior internal fixation with plate and screws. While our patient initially presented with a diastasis of 5.63 cm, we pursued nonoperative management with application of a pelvic binder and immediate physical therapy with unrestricted weight bearing. At 6-week follow-up, repeat imaging showed improvement of diastasis to 2.0 cm with significant improvement in symptoms. At 1-year follow-up, our patient is ambulating without assistance and is back to performing all activities of daily living and caring for her child.

At 1-year follow-up, our patient is ambulating without assistance and is back to performing all activities of daily living and caring for her child.

Prognosis is good for the majority of patients who experience postpartum pubic symphysis diastasis, and in most cases, full recovery without persistent pain is expected [1]. Follow-up radiographs in most case studies reviewed show near complete closure of the pubic symphysis and complete resolution of symptoms within 3 months. Some patients did require further physical therapy for up to 6 months including our patient presented above. No significant long-term sequelae have been identified. No definitive recommendations exist regarding alteration of care for future pregnancies, and this would be a good area for future study. We hope this case study provides insight for future treating physicians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

J.

J. Chawla, D. Arora, N. Sandhu, M. Jain, and A. Kumari, “Pubic symphysis diastasis: a case series and literature review,” Oman Medical Journal, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 510–514, 2017.

J. Chawla, D. Arora, N. Sandhu, M. Jain, and A. Kumari, “Pubic symphysis diastasis: a case series and literature review,” Oman Medical Journal, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 510–514, 2017.View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

J. J. Yoo, Y. C. Ha, Y. K. Lee, J. S. Hong, B. J. Kang, and K. H. Koo, “Incidence and risk factors of symptomatic peripartum diastasis of pubic symphysis,” Journal of Korean Medical Science, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 281–286, 2014.

View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

S. Najibi, M. Tannast, R. E. Klenck, and J. M. Matta, “Internal fixation of symphyseal disruption resulting from childbirth,” Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 732–739, 2010.

View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

J.

Borg-Stein and S. A. Dugan, “Musculoskeletal Disorders of Pregnancy, Delivery and Postpartum,” Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 459–476, 2007.

Borg-Stein and S. A. Dugan, “Musculoskeletal Disorders of Pregnancy, Delivery and Postpartum,” Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 459–476, 2007.View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

E. R. Howell, “Pregnancy-related symphysis pubic dysfunction management and postpartum rehabilitation: two case reports,” The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 102–111, 2012.

View at:

Google Scholar

J. M. Miller, L. K. Low, R. Zielinski, A. R. Smith, J. O. L. DeLancey, and C. Brandon, “Evaluating maternal recovery from labor and delivery: bone and levator ani injuries,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 213, no. 2, pp. 188.e1–188.e11, 2015.

View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

E.

R. Howell, “Pregnancy-related symphysis pubis dysfunction management and postpartum rehabilitation: two case reports,” The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 102–111, 2012.

R. Howell, “Pregnancy-related symphysis pubis dysfunction management and postpartum rehabilitation: two case reports,” The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 102–111, 2012.View at:

Google Scholar

R. Hagen, “Pelvic girdle relaxation from an orthopaedic point of view,” Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, vol. 45, no. 1-4, pp. 550–563, 1974.

View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

M. Shi, S. Shang, B. Xie et al., “MRI changes of pelvic floor and pubic bone observed in primiparous women after childbirth by normal vaginal delivery,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 294, no. 2, pp. 285–289, 2016.

View at:

Publisher Site | Google Scholar

Copyright

Copyright © 2019 Aaron Seidman et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Pubic Bone Injuries after First Childbirth: Utility of MR in detection and differential diagnosis of structural injury

1. Shek KL, Dietz HP. Intrapartum risk factors for levator trauma. BJOG. 2010;117(12):1485–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Christianson LM, Bovbjerg VE, McDavitt EC, Hullfish KL. Risk factors for perinealinjury during delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Kearney R, Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Obstetric factors associated with levator ani muscle injury after vaginal birth. ObstetGynecol. 2006;107:144–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Dietz H, Gillespie A, Phadke P. Avulsion of the pubovisceral muscle associated with large vaginal tear after normal vaginal delivery at term. Aust NZ J ObstetGynaecol. 2007;47:341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aust NZ J ObstetGynaecol. 2007;47:341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Dietz H, Lanzarone V. Levator trauma after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:707–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. DeLancey JO, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Kearney R, Guire K, Miller JM, Hussain H, Umek W, Hsu Y, Ashton-Miller JA. Comparison of levator ani muscle defects and function in women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. ObstetGynecol. 2007;109(2):295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. DeLancey JO, Kearney R, Chou Q, Speights S, Binno S. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. ObstetGynecol. 2003;101:46–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1101:266–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Miller J, Brandon C, Jacobson J, Low L, Zielinski R, Ashton-Miller J, DeLancey J. MRI findings concerning pelvic floor injury mechanisms in patients studied serially post first vaginal childbirth. AJR. 2010;195(3):786–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AJR. 2010;195(3):786–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Leadbetter RE, Mawer D, Lindow S. Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a review of the literature. Journal of Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Medicine. 2004;16:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Aslan E, Fynes M. Symphysial pelvic dysfunction. CurrOpinObstet and Gynecol. 2007;19:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Barnes GL, Kostenuik PJ, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Growth Factor Regulation of Fracture Repair. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(11):1805–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Datir AP, Saini A, Connell A, Saifuddin A. Stress-related bone injuries with emphasis on MRI. Clinical Radiology. 2007;62:828–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Diamond T, Clark W, Kumar S. Histomorphometric analysis of fracture healing cascade in acute osteoporotic vertebral body fractures. Bone. 2007:775–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Verrall GA, Henry L, Fazzalari N, Slavotinek J, Oakeshott R. Bone biopsy of the para-symphyseal pubic bone region in athletes with chronic groin injury demonstrates new woven bone formation consistent with a diagnosis of pubic bone stress injury. Am Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008;36:2425–2431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008;36:2425–2431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Cunningham PM, Brennan D, O’Connell M, MacMahon P, O’Neill P, Eustace S. Patterns of bone and soft-tissue injury at the symphysis pubis in soccer players: observations at MRI. AJR. 2007;188:W291–W296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Brennan D, O’Connell MJ, Ryan M, Cunningham P, Taylor D, Cronin C, O’Neill P, Eustace S. Secondary cleft sign as a marker of injury in athletes with groin pain: MR imaging appearance and interpretation. Radiology. 2005;235:162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Verrall GM, Slavotinek J, Fon G. Incidence of pubic bone marrow oedema in Australian rules football players: relation to groin pain. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:28–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Zoga AC, Kavanagh EC, Omar IM, Morrison WB, Koulouris G, Lopez H, Chaabra A, Domesek J, Meyers WC. Athletic pubalgia and the “sports hernia”, MR imaging findings. Radiology. 2008;247:797–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Kiuru M, Pihlajamaki H, Ahovuo J. Fatigue stress injuries of the pelvic bones and proximal femur: evaluation with MR imaging. EurRadiol. 2003;13:605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Zajick DC, Zoga M, Omar I, Meyers W. Spectrum of MIR findings in clinical athletic pubalgia. SeminMusculoskeletRadiol. 2008;12:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Mayerhoefer M, Kramer J, Breitenseher M, Norden C, Vakil-Adli A, Hofmann S, Meizer R, Siedentop H, Landsiedl F, Aigner N. MRI-Demonstrated outcome of subchondral stress fractures of the knee after treatment with Iloprost or Tramadol: observations in 14 patients. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Boks SS, Vroegindeweij D, Koes B, Hunink M, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Follow-up of occult bone lesions detected at MR imaging: systematic review. Radiology. 2006;238:853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Boks SS, Vroegindeweij D, Koes B, Bernsen R, Hunink M, Bierma-Zeinstra S. MRI Follow-up of posttraumatic bone bruises of the knee in general practice. AJR. 2007;189:556–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MRI Follow-up of posttraumatic bone bruises of the knee in general practice. AJR. 2007;189:556–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Garagiola D, Tarver R, Gibson L, Rogers R, Wass J. Anatomic change in the pelvis after uncomplicated vaginal delivery: A CT study on 14 women. AJR. 1989;153:1239–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Wurdinger S, Humbsch K, Reichenbach JR, Pelker G, Seewald HJ, Kaiser WA. MRI of the pelvic ring joints postpartum: normal and pathological findings. J MagnResonImaging. 2002;15:324–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Hermann KG, Halle H, Reisshauer A, Schink T, Vsianska L, Muhler MR, Lembcke A, Hamm B, Bollow M. Peripartum changes of the pelvic ring: usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging. Rofo. 2007;179:1243–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Maldjian C, Adam R, Maldjian J, Smith R. MRI appearance of the pelvis in the post cesarean-section patient. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1999;17:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Hayat S, Thorp J, Kuller J, Brown B, Semelka R. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic floor in the postpartum patient. IntUrogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7(6):321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic floor in the postpartum patient. IntUrogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7(6):321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Novellas S, Chassang M, Verger S, Bafghi A, Bongain A, Chevallier P. MR features of the levator ani muscle in the immediate postpartum following cesarean delivery. IntUrogynecolJ. 2010;21:563–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Lien K-C, Mooney B, DeLancey JOL, Ashton-Miller JA. Levator ani muscle stretch induced by simulated vaginal birth. ObstetGynecol. 2004;103:31–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Brandon C, Jacobson J, Fessell D, Dong Q, Morag Y, Girish G, Jamadar D. Groin Pain Beyond the Hip: How Anatomy Predisposes to Injury as Demonstrated by Musculoskeletal Ultrasound and MR Imaging. AJR. In press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Why childbirth is so hard and dangerous

- Colin Barras

- BBC Earth

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you sort things out. Image credit: iStock However, recent research shows that this is not the only thing, says BBC Earth 9 columnist 0017 .

Image credit: iStock However, recent research shows that this is not the only thing, says BBC Earth 9 columnist 0017 .

The birth of a child is a long and painful process, and sometimes deadly. According to the World Health Organization, about 830 women die every day due to complications during pregnancy and childbirth (which, however, is 44% lower than in 1990).

"These statistics are astounding," says Jonathan Wells of University College London, who studies infant nutrition. "Female mammals have never had to pay such a high price for offspring."

- Russian woman who gave birth to 69 children: truth or fiction?

- Pregnancy and childbirth in the UK: free and without a doctor

- Can you determine the sex of a child by the size of the mother's belly?

- "Age is one day": the first hours of a new life

But why is childbirth so dangerous for women? And what can we do to reduce the death rate?

Scientists first began to think about the causes of such dramatic childbirth in women in the middle of the 20th century. They quickly, as it seemed then, found an explanation.

They quickly, as it seemed then, found an explanation.

Problems with childbearing began in the earliest members of our evolutionary lineage, the hominins, who diverged from other primates about seven million years ago.

These were animals that had little in common with us today, except, perhaps, for the fact that already in those distant times, like us, they walked on two legs.

Photo copyright JUAN MANUEL BORRERO/naturepl.com

Photo captionHominins have been moving upright for millions of years

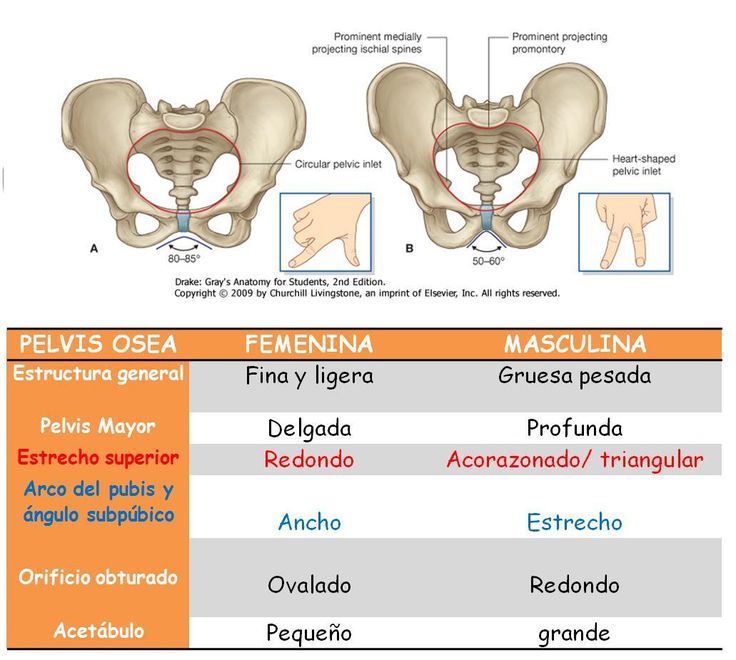

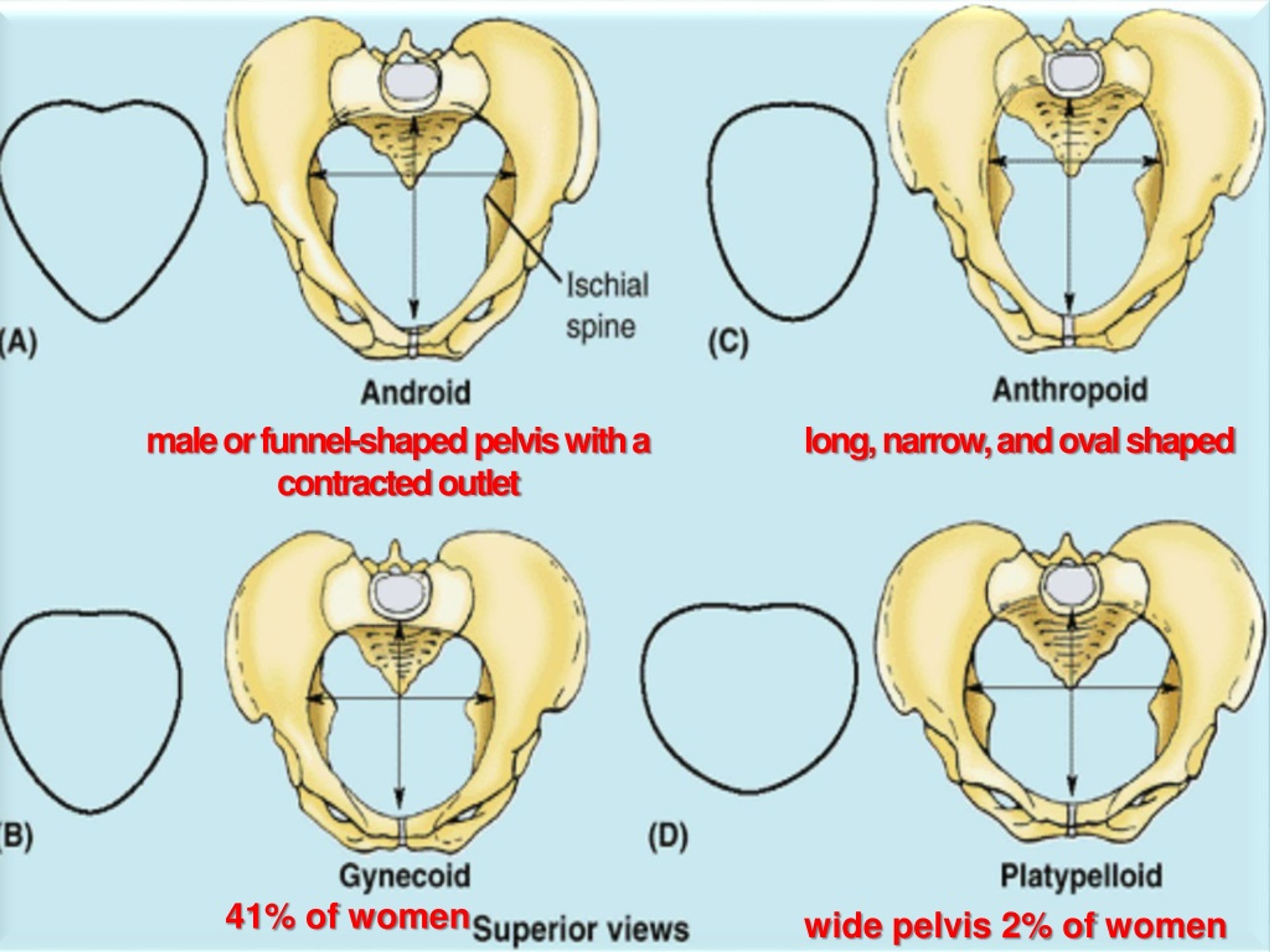

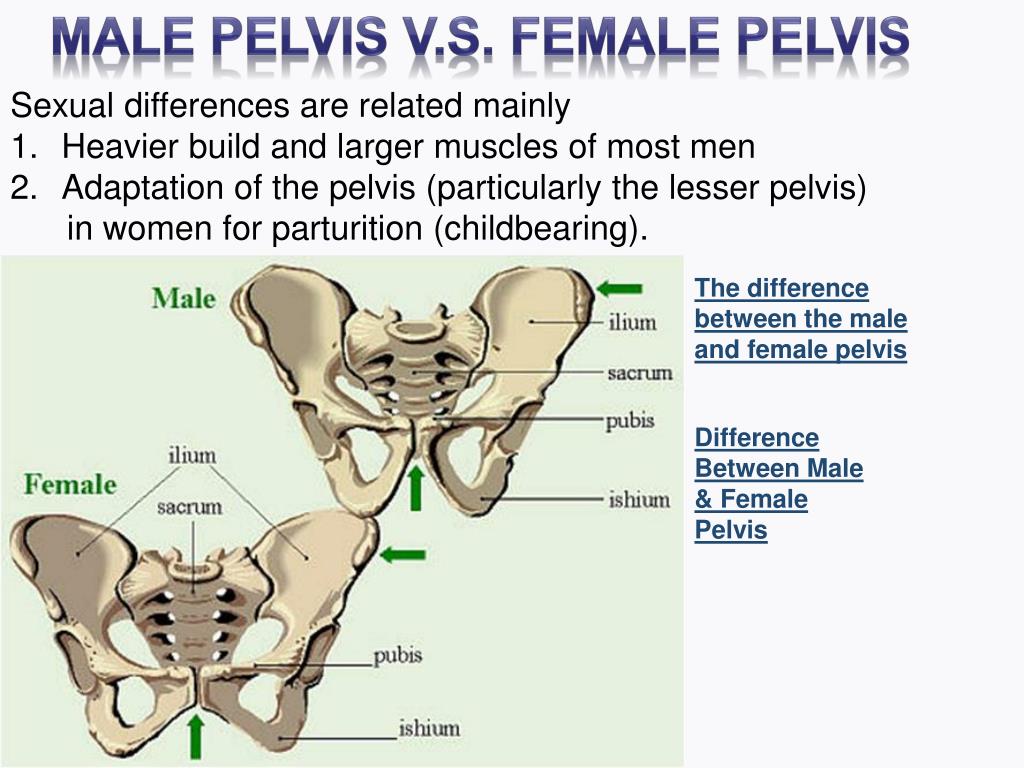

Bipedalism caused the hominin skeleton to change - it stretched out, and this affected the shape of the pelvis.

In most primates, the birth canal is relatively straight. Among the hominins, they soon changed quite markedly. The hips became narrower, and the birth canal curved.

Thus, at the dawn of our history, hominin babies had to twist and turn in order to squeeze through the birth canal. This made the birth process very difficult.

This made the birth process very difficult.

But things soon got worse.

About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to change again. They lost their ape-like features and became more like modern humans.

Their bodies have become a little longer, their arms have shortened, and their brains have noticeably enlarged. And this last detail was bad news especially for women.

Image copyright, Science Photo Library

Image caption,Around two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to lose their ape-like features and become more like modern humans

It seems that evolution has begun to contradict itself. On the one hand, the pelvis of women had to narrow so that they could move on two legs, on the other hand, the babies they carried had an enlarged head, complicating the process of passing through the already narrow birth canal.

Childbirth has become an incredibly painful and potentially dangerous business, which it has remained to this day.

In 1960, the anthropologist Sherwood Washburn called this theory the "obstetrical dilemma" and this explanation satisfied many scientists. But not everyone.

Holly Dunsworth of the University of Rhode Island was initially fascinated by Washburn's theory, but later realized that a lot of it didn't add up.

According to Washburn, when the human brain expanded two million years ago, the woman's body began to adapt to this, and the duration of pregnancy was noticeably reduced.

Photo credit, Science Photo Library/Alamy

Photo caption,Many women use pain relief during childbirth

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

And it seems like a pretty logical hypothesis: babies began to be born at an earlier stage of development, and anyone who has ever seen a newborn baby will attest to how helpless and vulnerable he is.

However, Dunsworth believes that this is simply not true.

"Our babies are born quite large, and women's pregnancies last 37 days longer than monkeys of the same size," explains the researcher.

The same applies to the size of the brain. Females give birth to babies with larger heads than females of other primates, with about the same body weight as females. And this means that the key points of Washburn's hypothesis are false.

And that's not all. The central assumption of the obstetrical dilemma is that the size and shape of the human pelvis, in particular in women, has changed greatly due to our habit of walking in an upright position.

However, if evolution were to solve the problem of childbirth in humans, it would certainly have already made women's hips and, accordingly, the birth canal a little wider.

Our ability to walk on two legs would not be affected at all.

Photo credit, Visuals Unlimited/naturepl. com

com

Men's (left) and women's (right) pelvises

In 2015, researchers from Harvard University conducted an experiment that involved men and women with different body types.

The researchers observed the physical activity of volunteers in the lab and found that those with wider hips had no problem walking or running.

So, if nature, through evolution, made women's hips a little wider and thus facilitated childbearing, women's ability to move would not deteriorate.

According to Dunsworth, the length of a woman's pregnancy is not determined by the size of the baby's brain, as the obstetrical dilemma suggests.

The fact is that a woman's body is simply not able to feed a fetus that requires too much energy for longer than 39-40 weeks.

So, the reason for this length of pregnancy is not the difficulty of passing the child through the birth canal, as Washburn believed.

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Fetus on CT scan

What then is the true cause of difficult labor in women? In 2012, researcher Jonathan Wells of University College London and his team began to study the history of childbirth and came to a startling conclusion.

For most of human evolution, it was obviously much easier to have a baby than it is now.

From the little evidence that remains today, it follows that in early hunter-gatherer societies, childbirth was one of the smallest problems.

Archaeologists find almost no skeletons of babies from this period, which indicates a relatively low mortality rate in early childhood.

But the situation changed dramatically a few thousand years ago, when people switched to a sedentary lifestyle.

Many more newborn bones appear in the archaeological record from the early agricultural era.

Photo copyright, Volker Steger/4 million years of man/SPL

Photo caption,Homo erectus, the immediate ancestor of modern humans, could have had a much easier birth process…

On the one hand, living in a more populous community led to outbreak of infectious diseases, and newborns, as the most vulnerable, became their victims.

On the other hand, the diet of farmers with a high content of carbohydrates began to differ markedly from the diet of hunter-gatherers, which was dominated by proteins.

This provoked changes in the body structure: the agriculturalists, as evidenced by archaeological finds, were significantly shorter than the hunter-gatherers.

And scientists who study childbirth are well aware that the shape and size of a woman's pelvis directly depends on her height.

The smaller the woman, the narrower her hips - hence the transition to agriculture has complicated the process of childbearing.

On the other hand, a carbohydrate-rich diet has made babies gain weight faster in the womb, and it is much more difficult to give birth to a large baby.

Photo copyright, Jose Antonio Penas/Science Photo Library

Photo caption,Farming has once again changed our bodies

Thus, about 10 thousand years ago, childbirth, which for millions of years was a relatively easy process for humans, suddenly become a problem.

However, according to Holly Dunsworth, this is not the end of the story.

Scientific evidence shows that a woman's pelvis is at its best for childbirth around the age of 20, when she reaches her peak fertility, and stays that way until about 40 years of age.

After that, it gradually changes its shape, preparing for menopause, and becomes less suitable for the birth of a child.

The question arises: if so many evolutionary factors influenced the characteristics of childbirth, maybe this process continues to this day?

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,Pregnancy is sometimes debilitating for a woman

In December 2016, scientists Fischer and Mittereker published a sensational paper on this topic.

Previous studies have suggested that larger babies are more likely to survive, and that infant size at birth is to some extent a hereditary factor.

The growth of a medium-sized fetus is evolutionarily limited by the width of the female pelvis. But many babies are now being born by caesarean section.

But many babies are now being born by caesarean section.

- Top of evolution: caesarean section lets the weak survive

Consequently, Fischer and Mittereker believe that in societies where caesarean section is gaining popularity, babies will be born ever larger.

Image copyright, iStock

Image caption,In some parts of the world, the female body may be evolving towards larger babies

Theoretically, the number of times a baby is too big to be born naturally could increase by 10-20 % within just a few decades, at least in some parts of our planet.

Or, in other words, the body of a woman in these societies can evolve towards the birth of larger babies.

So far, this is just an idea, and there is no convincing evidence for it, but it is a rather interesting assumption.

From the moment birth began to change under the influence of evolution, the size of the fetus has always been limited to a certain extent by the size of the birth canal.

But it may not matter to some children.

Read the original of this article in English at BBC Earth .

Pelvic fracture - causes, symptoms, who treats

A pelvic fracture is a break in the integrity of one or more pelvic bones.

What should be done to diagnose and treat a pelvic fracture ? To solve this problem, the first step for the patient is to make an appointment with a traumatologist. After the initial examination, the doctor may prescribe additional tests:

- CT scan of the pelvic bones

- X-ray of pelvic bones

- Bladder ultrasound

- MRI of the sacroiliac joints.

The pelvis is the area of the body below the abdomen between the pelvic bones. The pelvic area includes the following bones:

- sacrum - a large triangular bone at the base of the spine

- coccyx - tail bone

- pelvic bones, which include the ilium, ischium and pubic bone

Together these bones form the so-called pelvic ring. The pelvis is a very stable structure that protects many important nerves, blood vessels, and organs, including the internal reproductive organs, the bladder, and the lower digestive tract. It also serves as a support for the leg muscles.

The pelvis is a very stable structure that protects many important nerves, blood vessels, and organs, including the internal reproductive organs, the bladder, and the lower digestive tract. It also serves as a support for the leg muscles.

Types of pelvic fractures

Since the pelvis is made up of several bones, there are many types of fractures. There are also several types of pelvic fractures, depending on the nature of the fracture, including:

- closed or open fractures. If the fracture does not break the surrounding skin, such a fracture is called closed. If a broken bone breaks the skin, it is called an open or compound fracture

- complete fractures: a complete fracture occurs when a bone breaks in two

- displaced fractures: when there is a gap in the bone fracture, it is called a displaced fracture

- partial fractures: a partial fracture occurs when the injury does not go through the entire bone

- stress fractures: A stress fracture occurs when a bone breaks.

In addition to the specific form of the fracture, a pelvic fracture is also classified as stable or unstable:

- stable pelvic fracture: in a stable pelvic fracture, there is usually only one fracture and the broken parts of the bones do not move. Pelvic fractures resulting from minor impacts, such as a small fall or running, are usually stable

- unstable pelvic fracture: an unstable pelvic fracture often has 2 or more fractures, and the ends of the broken parts of the bones are misaligned. Unstable pelvic fractures most often result from a strong blow, such as in a car accident.

Although this type of fracture is less common, there is another type of pelvic fracture called a ruptured fracture. A ruptured fracture occurs when a tendon or ligament breaks away from the bone it is attached to, taking a small piece of bone with it.

Risk factors

A pelvic fracture can occur in anyone at any age. Minor pelvic fractures are more common in older patients because they are more likely to develop conditions that weaken the bones, such as osteoporosis. Severe pelvic fractures are more common in patients aged 15 to 28 years. Men under the age of 35 are more likely to have a pelvic fracture, and women are more likely to have fractures after the age of 35.

Severe pelvic fractures are more common in patients aged 15 to 28 years. Men under the age of 35 are more likely to have a pelvic fracture, and women are more likely to have fractures after the age of 35.

Pelvic fracture symptoms

The symptoms of a pelvic fracture depend on the severity of the injury. The symptoms are as follows:

- pain in the groin, hip or lower back

- Increased pain when walking or moving the legs

- numbness or tingling in the groin or legs

- abdominal pain

- difficult urination

- difficulty walking or standing

Pelvic fracture causes

Pelvic fractures are caused by several situations and conditions, including:

- Strong impact: Because the pelvis is a very stable bone structure, most pelvic fractures result from strong impacts, such as a car accident or a fall from a significant height. Impact usually causes unstable pelvic fractures

- diseases that weaken bones: diseases such as osteoporosis contribute to pelvic fractures

- sports activities: those who play sports may experience a pelvic fracture, known as an avulsion fracture.

It occurs when a tendon or ligament breaks away from the bone it is attached to. When a tendon or ligament ruptures, it takes a small part of the bone with it. Avulsion fracture of the pelvic bones is usually stable

It occurs when a tendon or ligament breaks away from the bone it is attached to. When a tendon or ligament ruptures, it takes a small part of the bone with it. Avulsion fracture of the pelvic bones is usually stable

How a Doctor Diagnoses a Pelvic Fracture

All pelvic fractures require x-rays to diagnose. The traumatologist will refer the patient to other imaging studies to learn more about the injury:

- X-ray of the pelvic bones. During the procedure, doctors use radiation to take pictures of the bones. All pelvic fractures require x-rays so the doctor can see how much of the pelvis is broken and how weak or severe the fracture is

- CT scan of the pelvis: In a CT scan, the doctor uses several x-rays taken from different angles of the patient's body to obtain detailed images. CT provides more detailed images of bones than conventional x-rays

- MRI of the coccyx and sacroiliac joints: The doctor will refer the patient for an MRI if he cannot obtain enough information about the fracture using x-rays and computed tomography.

How a doctor treats a pelvic fracture

The treatment of a pelvic fracture depends on several factors, including:

- the severity of the injury

- nature and type of fracture

- which bones are displaced and how much they are displaced

- general health and other injuries.

Treatment of minor and stable fractures in which the bones do not move usually does not require surgery. Treatment for a stable fracture includes:

- rest: your doctor will recommend rest as much as possible to avoid stress and pressure on the fracture

- walking aids: Depending on the location of the pelvic fracture, the doctor will ask you to use walking aids such as crutches, a wheelchair to avoid strain on the leg

- medicines: The doctor will prescribe medicines to relieve pain. He will also ask you to take blood thinners to reduce the risk of blood clots in the veins of your legs and pelvis

A more severe or unstable pelvic fracture usually requires one or more surgeries. Different types of surgery for pelvic fractures include:

Different types of surgery for pelvic fractures include:

- external fixation: Doctors use external fixation to stabilize the pelvis after a pelvic fracture. In this operation, metal pins or screws are inserted into the bone through small incisions in the skin and muscles. Pins and screws emerge from the skin on either side of the pelvis and are attached to rods on the outside of the body. The resulting system acts as a stabilizing frame, keeping broken bones in the correct position while the fractures heal

- Skeletal Traction: Skeletal traction is a system of pulleys on the outside of the body that helps straighten broken bone fragments. In skeletal traction, the surgeon inserts metal pins into the femur or tibia that stick out of the skin and help position the leg in the correct position. Weights attached to pins gently pull on the leg, holding broken pelvic bone fragments in a more normal position

- Open reduction and internal fixation: In open reduction and internal fixation, displaced pelvic bone fragments are first returned to their normal position.

The fragments are then fixed with screws or metal plates that are attached to the outside of the bone

The fragments are then fixed with screws or metal plates that are attached to the outside of the bone

Patients who sustain a severe pelvic fracture in a high-impact accident often have other injuries or organ damage caused by the fracture that must also be treated. In these cases, the success of the treatment of a pelvic fracture often depends on the success of the treatment of associated injuries.

Can a pelvic fracture heal without treatment

Mild and stable pelvic fractures usually heal without medical intervention. However, if there is a slight fracture of the pelvic bones, you should limit the load on the legs and rest. If you suspect a fracture of the pelvic bones, you should contact a traumatologist as soon as possible.

The best doctors of St. Petersburg

Abzianidze Alexey Vadimovich

Rating: 5 / 5

Enroll

Aliev Murad Ramazanovich

Rating: 5 / 5

Enroll

Angelcheva Tatyana Avramovna

Rating: 4. 8 / 5

8 / 5

Enroll

Antonov Ilya Alexandrovich

Rating: 4.8 / 5

Enroll

Akhmedov Kazali Muradovich

Rating: 4.9 / 5

Enroll

Bayzhanov Abylkhair

Rating: 4.6 / 5

Enroll

Share:

Scientific sources:

- Shchetkin V.A. Treatment of injuries of bones and joints of the pelvis in patients with polytrauma: Abstract of the thesis. dis. Dr. med. Sciences. - M., 1999. - 46 p.

- Relin VE Traumatic syndrome of the sacroiliac joint in patients with fractures of the anterior half-ring of the pelvis: Abstract of the thesis. dis. cand. honey. Sciences. - M., 1999. - 17 p.

- Matthias Hofer Ultrasonic diagnostics.// Ed. Honey. Lit. MSC. 2006 106 page

- Mikhailov M K Differential X-ray diagnostics of diseases of bones and joints / M.K. Mikhailov.

G.I. Volodin. E.K Laryukova. Kazan, Tatar book. nzd-vo, 1988. - 168 p.

G.I. Volodin. E.K Laryukova. Kazan, Tatar book. nzd-vo, 1988. - 168 p. - Clinical Guide to Ultrasound Diagnostics / Ed. V.V. Mitkov. - M.: Vidar, 1997. - T. IV. - S. 229-231.

Useful information

Pain in the sacrum

What needs to be done to diagnose and treat pain in the sacrum? To solve this problem, the first step for the patient is to make an appointment with an orthopedist. After the initial examination, the doctor may prescribe additional studies: Consultation with a neurologist MRI of the lumbosacral spine MRI of the sacroiliac joints CT scan of the lumbosacral spine CT scan of the pelvis MRI of the hip joints.

read more +

osteosclerosis

What should be done to diagnose and treat osteosclerosis? To solve this problem, the first step for the patient is to make an appointment with a traumatologist. After the initial examination, the doctor may prescribe additional studies: CT scan of the pelvis Scintigraphy.