How child acquire his first language

FAQ: Language Acquisition | Linguistic Society of America

How do children acquire language? Do parents teach their children to talk?

No. Children acquire language quickly, easily, and without effort or formal teaching. It happens automatically, whether their parents try to teach them or not.

Although parents or other caretakers don't teach their children to speak, they do perform an important role by talking to their children. Children who are never spoken to will not acquire language. And the language must be used for interaction with the child; for example, a child who regularly hears language on the TV or radio but nowhere else will not learn to talk.

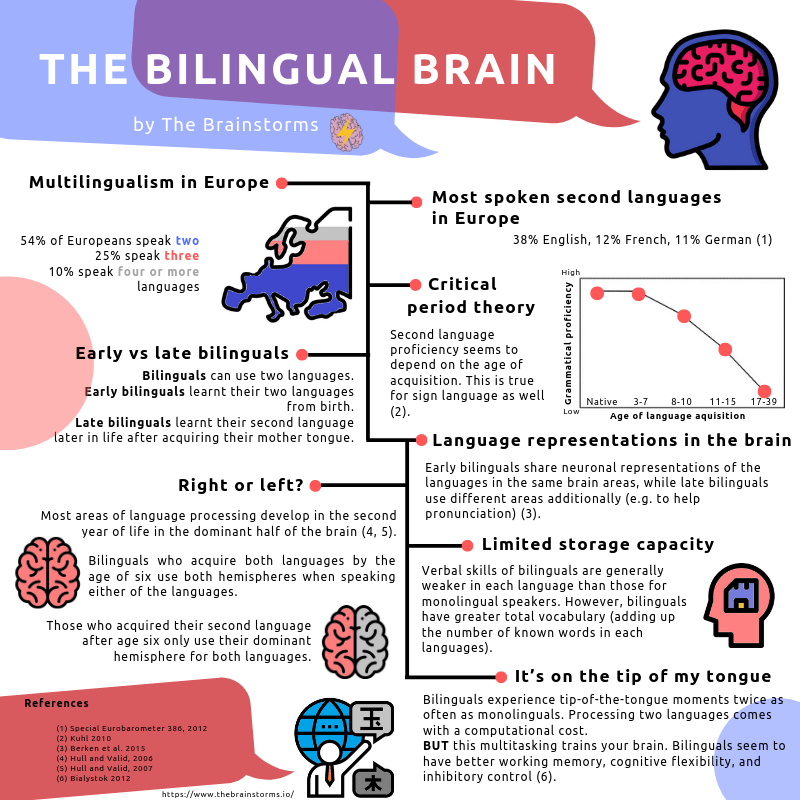

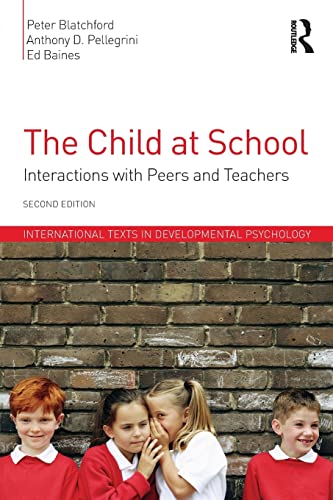

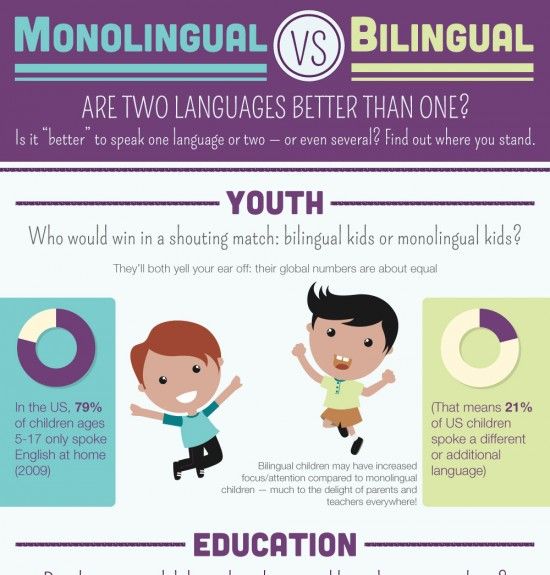

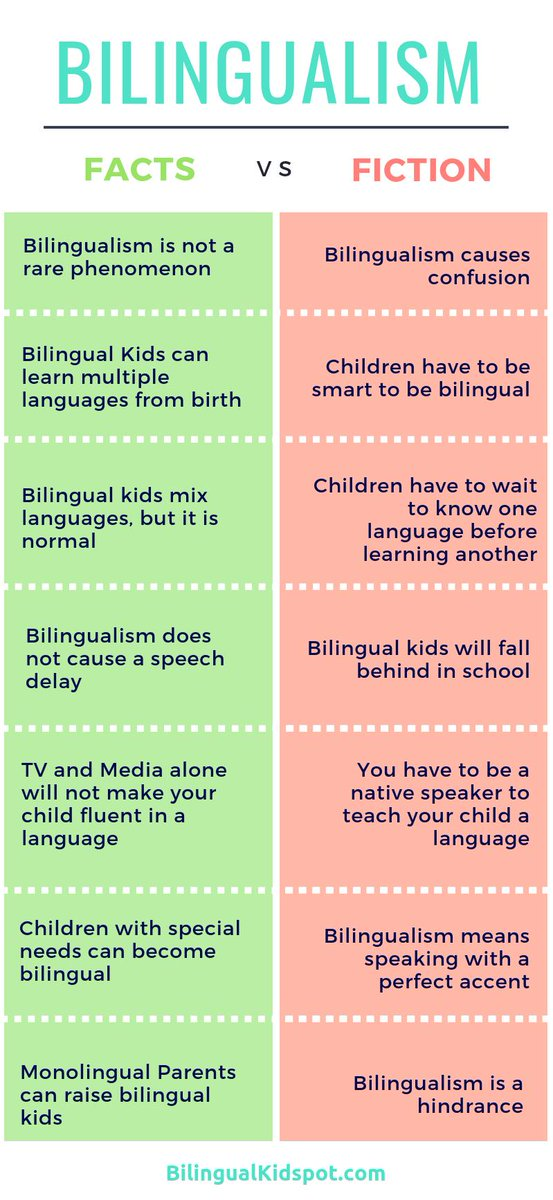

Children acquire language through interaction - not only with their parents and other adults, but also with other children. All normal children who grow up in normal households, surrounded by conversation, will acquire the language that is being used around them. And it is just as easy for a child to acquire two or more languages at the same time, as long as they are regularly interacting with speakers of those languages.

The special way in which many adults speak to small children also helps them to acquire language. Studies show that the 'baby talk' that adults naturally use with infants and toddlers tends to always be just a bit ahead of the level of the child's own language development, as though pulling the child along. This 'baby talk' has simpler vocabulary and sentence structure than adult language, exaggerated intonation and sounds, and lots of repetition and questions. All of these features help the child to sort out the meanings, sounds, and sentence patterns of his or her language.

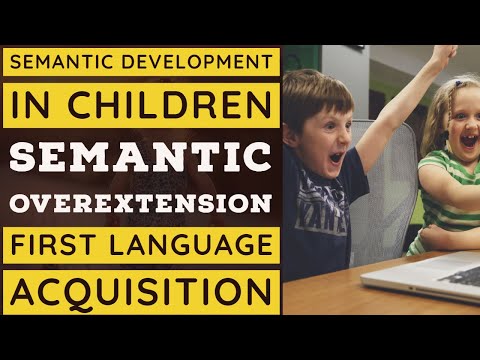

When do children learn to talk?

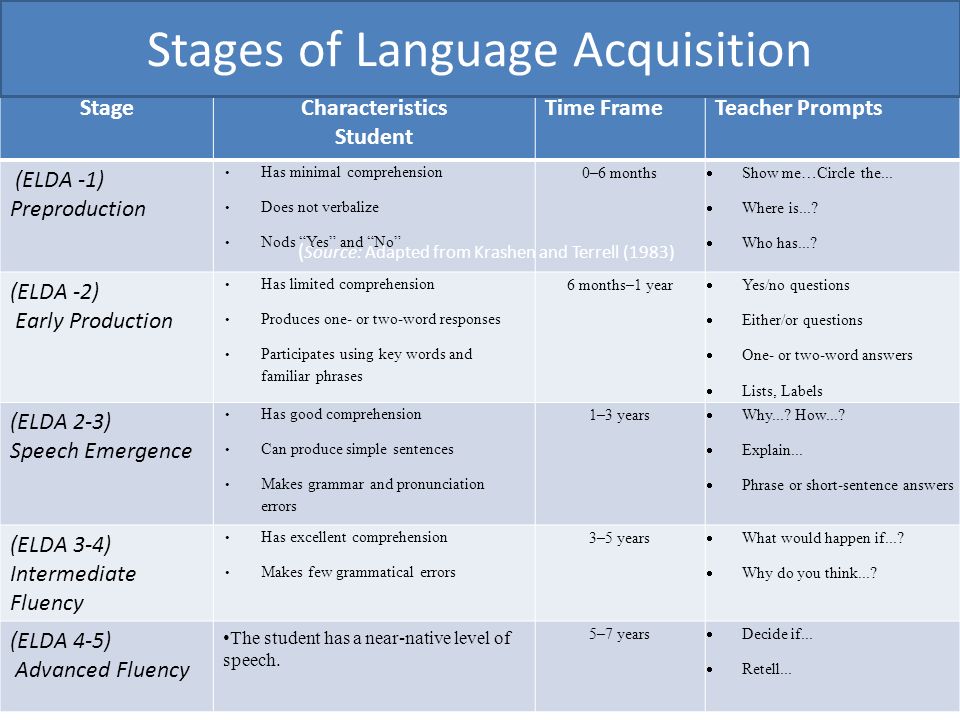

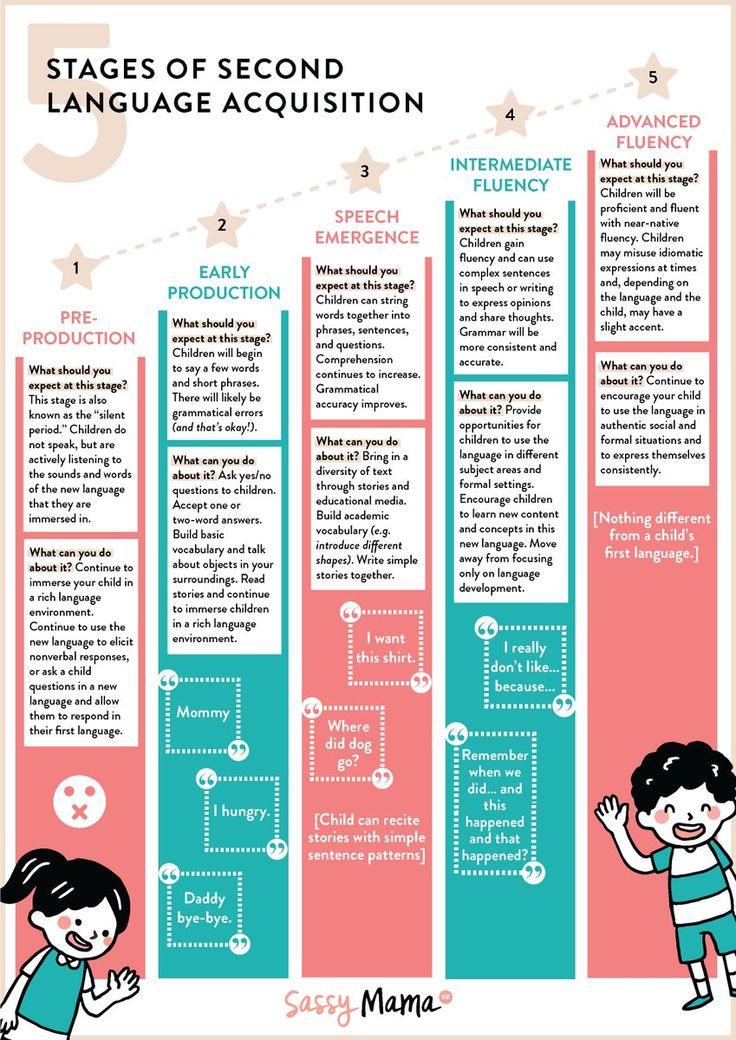

There is no one point at which a child learns to talk. By the time the child first utters a single meaningful word, he or she has already spent many months playing around with the sounds and intonations of language and connecting words with meanings. Children acquire language in stages, and different children reach the various stages at different times. The order in which these stages are reached, however, is virtually always the same.

The first sounds a baby makes are the sounds of crying. Then, around six weeks of age, the baby will begin making vowel sounds, starting with aah, ee, and ooh. At about six months, the baby starts to produce strings of consonant-vowel pairs like boo andda. In this stage, the child is playing around with the sounds of speech and sorting out the sounds that are important for making words in his or her language from the sounds that aren't. Many parents hear a child in this stage produce a combination like "mama" or "dada" and excitedly declare that the child has uttered his or her first word, even though the child probably didn't attach any meaning to the 'word'.

Somewhere around age one or one and a half, the child will actually begin to utter single words with meaning. These are always 'content' words like cookie, doggie, run,and see - never 'function' words like and, the, and of. Around the age of two, the child will begin putting two words together to make 'sentences' like doggie run. A little later on, the child may produce longer sentences that lack function words, such as big doggie run fast. At this point all that's left to add are the function words, some different sentence forms (like the passive), and the more complex sound combinations (like str). By the time the child enters kindergarten, he or she will have acquired the vast majority of the rules and sounds of the language. After this, it's just a matter of combining the different sentence types in new ways and adding new words to his or her vocabulary.

A little later on, the child may produce longer sentences that lack function words, such as big doggie run fast. At this point all that's left to add are the function words, some different sentence forms (like the passive), and the more complex sound combinations (like str). By the time the child enters kindergarten, he or she will have acquired the vast majority of the rules and sounds of the language. After this, it's just a matter of combining the different sentence types in new ways and adding new words to his or her vocabulary.

Why did my daughter say feet correctly for a while, and then go back to calling them foots?

Actually, she hasn't 'gone back' at all; she's gone forward. When she used the wordfeet as a toddler, she was just imitating what she had heard. But now she has learned a rule for making plurals, which is that you add the s sound to the end of the word. So she's just applying her new rule to all nouns - even the exceptions to the rule, likefoot/feet. She'll probably do the same thing when she learns to add ed to verbs to make the past tense, saying things like he standed up until she learns that stand/stoodis an exception to the rule. She'll sort it all out eventually, but for now, rest assured that this is progress; it's evidence that she's going beyond imitation and actually learning the rules of the English language.

She'll probably do the same thing when she learns to add ed to verbs to make the past tense, saying things like he standed up until she learns that stand/stoodis an exception to the rule. She'll sort it all out eventually, but for now, rest assured that this is progress; it's evidence that she's going beyond imitation and actually learning the rules of the English language.

How can a child who can't even tie her own shoes master a system as complex as the English language?

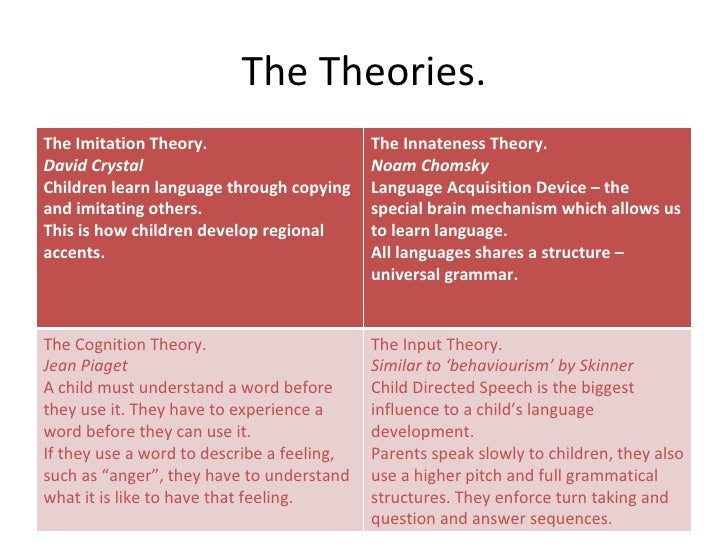

Although the 'baby talk' that parents use with small children may help them to acquire language, many linguists believe that this still cannot explain how infants and toddlers can acquire such a complicated system so easily.

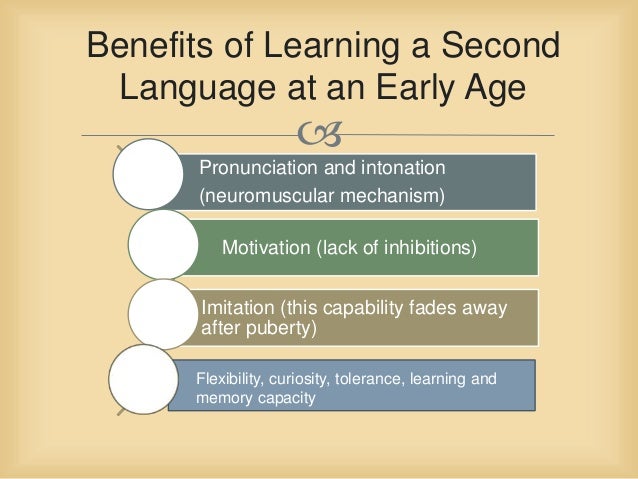

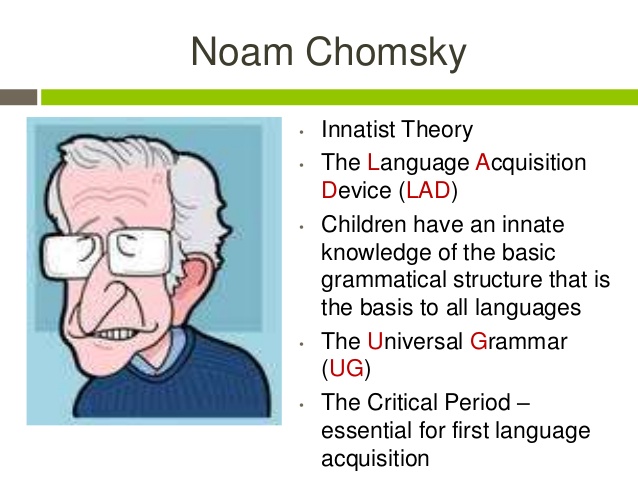

It's far easier for a child to acquire language as an infant and toddler than it will be for the same child to learn, say, French in a college classroom 18 years later. Many linguists now say that a newborn's brain is already programmed to learn language, and in fact that when a baby is born he or she already instinctively knows a lot about language. This means that it's as natural for a human being to talk as it is for a bird to sing or for a spider to spin a web. In this sense, language may be like walking: The ability to walk is genetic, and children develop the ability to walk whether or not anybody tries to teach them to do so. In the same way, children develop the ability to talk whether or not anybody tries to teach them. For this reason, many linguists believe that language ability is genetic. Researchers believe there may be a 'critical period' (lasting roughly from infancy until puberty) during which language acquisition is effortless. According to these researchers, changes occur in the structure of the brain during puberty, and after that it is much harder to learn a new language.

This means that it's as natural for a human being to talk as it is for a bird to sing or for a spider to spin a web. In this sense, language may be like walking: The ability to walk is genetic, and children develop the ability to walk whether or not anybody tries to teach them to do so. In the same way, children develop the ability to talk whether or not anybody tries to teach them. For this reason, many linguists believe that language ability is genetic. Researchers believe there may be a 'critical period' (lasting roughly from infancy until puberty) during which language acquisition is effortless. According to these researchers, changes occur in the structure of the brain during puberty, and after that it is much harder to learn a new language.

Linguists have become deeply interested in finding out what all 5,000 or so of the world's languages have in common, because this may tell us what kinds of knowledge about language are actually innate. For example, it appears that all languages use the vowel sounds aah, ee, and ooh - the same vowel sounds a baby produces first. By studying languages from all over the world, linguists hope to find out what properties all languages have in common, and whether those properties are somehow hard-wired into the human brain. If it's true that babies are born with a lot of language knowledge built in, that will help to explain how it's possible for a very small child - with no teaching, and regardless of intelligence level - to quickly and easily acquire a system of language so complex that no other animal or machine has ever mastered it.

By studying languages from all over the world, linguists hope to find out what properties all languages have in common, and whether those properties are somehow hard-wired into the human brain. If it's true that babies are born with a lot of language knowledge built in, that will help to explain how it's possible for a very small child - with no teaching, and regardless of intelligence level - to quickly and easily acquire a system of language so complex that no other animal or machine has ever mastered it.

For further information

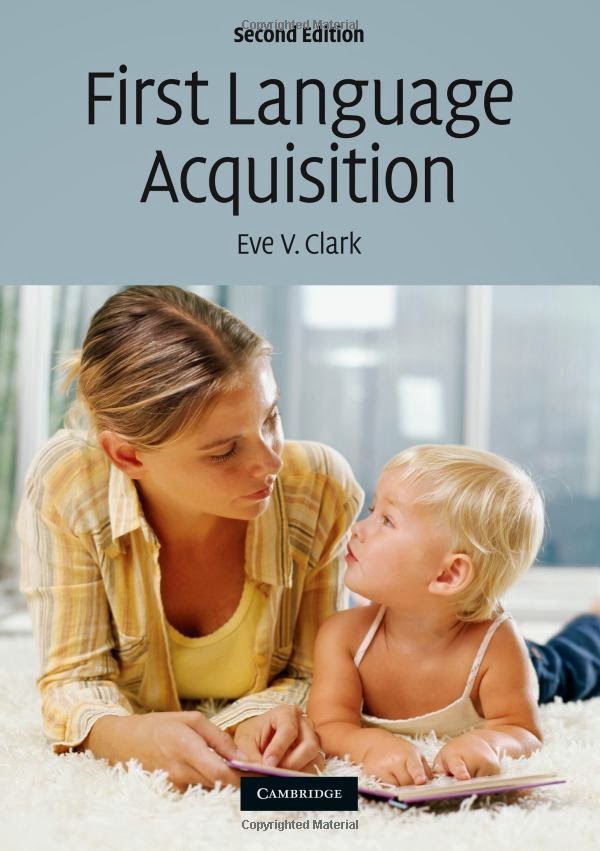

Pecchi, Jean Stillwell. 1994. Child Language. London: Routedge.

Pinker, Steven. 1994. The Language instinct. New York: W.W.Morrow.

"Playing the Language Game." Program Two: Acquiring the Human Language. The Human Language Series. Videocassette. New York: Equinox Films, 1995.

Smith, Neil. 1989. The Twitter Machine: Reflections on Language. Oxford: Blackwell.

FAQ by: Betty Birner

Download this document as a pdf.

Interested in more on this topic? Check out Language in Children and more books from LSA here.

How do children acquire language?

Children start learning a language from birth, going from babbling to being able to communicate their wants and needs clearly, and continue their learning throughout their lives. TRT World asked linguists how this miraculous occurrence takes place.

“Children,” says Professor Emeritus of Linguistics Sumru Ozsoy of Bogazici University, “are not trained or taught in terms of language. They internalise from the day they are born to up to three years the language system of the adults surrounding them.”

She clarifies: “No adult tells them ‘This is how you structure a sentence in Turkish’ and teaches them.”

Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Linguistics Dan Slobin of UC Berkeley further explains: “Any child, anywhere in the world, can learn to speak and understand a language simply by interacting with other people who use the language. Two factors are important: (1) hearing the language (or, for deaf children, seeing the language in the form of hand signs), and (2) interacting with speakers (or signers).”

Two factors are important: (1) hearing the language (or, for deaf children, seeing the language in the form of hand signs), and (2) interacting with speakers (or signers).”

According to Slobin, interaction is “critical” because the child learns what words mean by using them and seeing how people respond, and by trying to follow instructions, make requests, answer questions and more.

In an email interview with TRT World, Slobin says you cannot learn a language just by watching TV: “You need to be part of the conversation. Parents and other caregivers have to engage the child in talk—ask questions, give explanations—and encourage children to ask questions and to talk about their own experiences.”

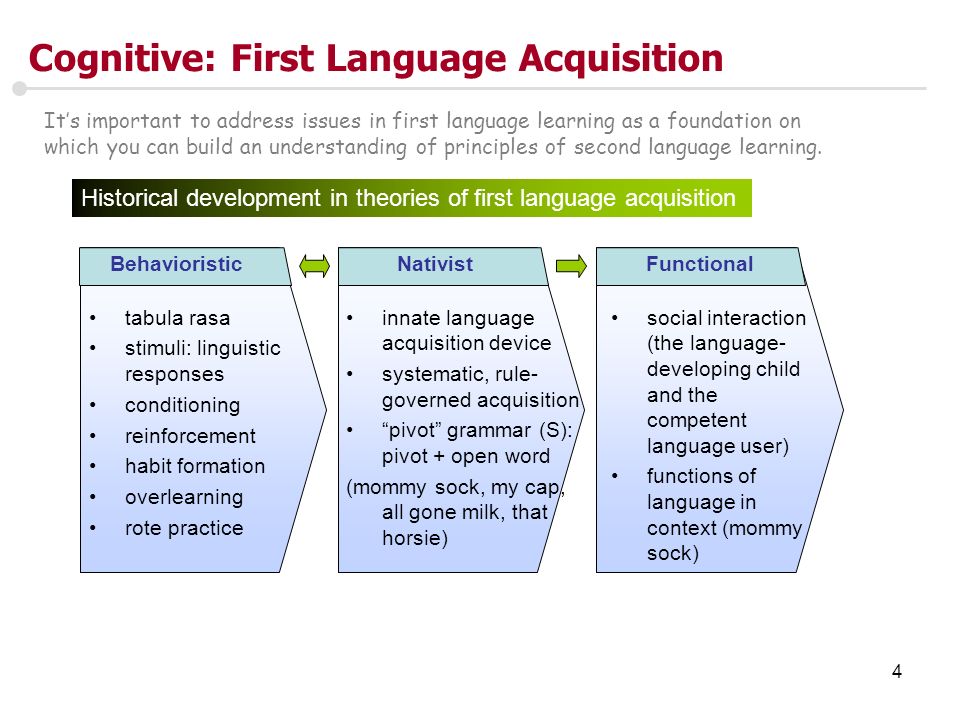

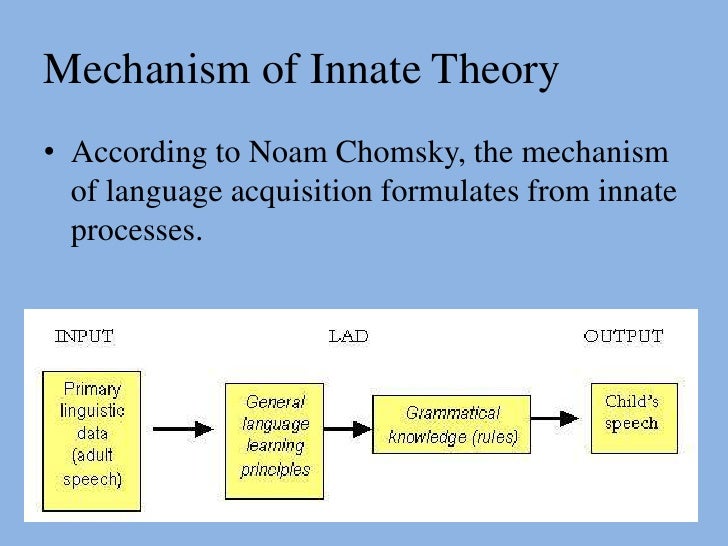

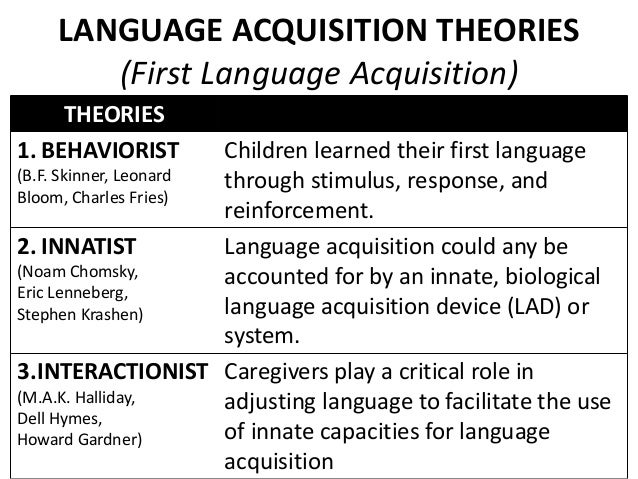

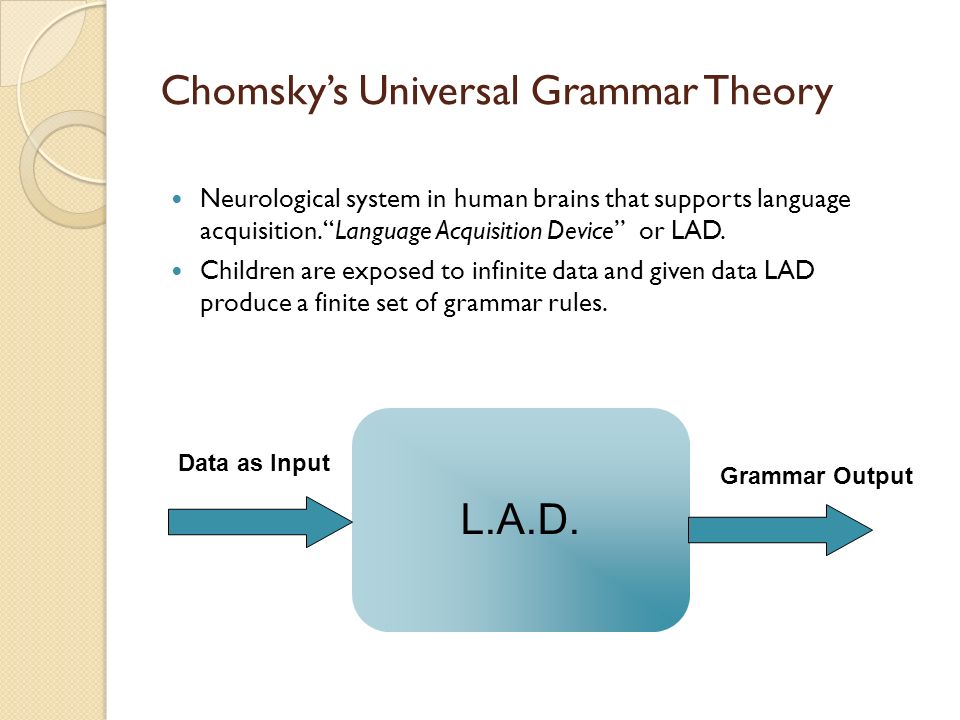

In a phone interview with TRT World, Ozsoy says there is an assumption that there’s a cognitive system for a language acquisition device. This concept, generative grammar, is one of Noam Chomsky’s propositions: all children are born with a predisposition to acquire a human language.

Ozsoy notes that Chomsky’s theory, which has been around for decades, has been challenged on a regular basis.

“Yet,” she notes, “the challenge remains a challenge.” She further explains that the challengers have not been able to completely disprove Chomsky’s theory, which has undergone modifications during the long time it has been around.

According to Ozsoy, the innateness hypothesis says language is innate to us – not a specific language but Universal Grammar – there is a model of Universal Grammar that every human child is born with. “What the child does is once he or she starts getting the input from his environment the child starts superimposing, mapping the data onto this internal language, internal system. Starts forming his own grammar of his native language.”

Ozsoy says “Chomsky does say and emphasise the significance of primary linguistic data. That the child has to be involved. It does not mean that just because the child is born with this innate system that the child will be able to realise his full potential. No. The child has to be exposed to data.”

No. The child has to be exposed to data.”

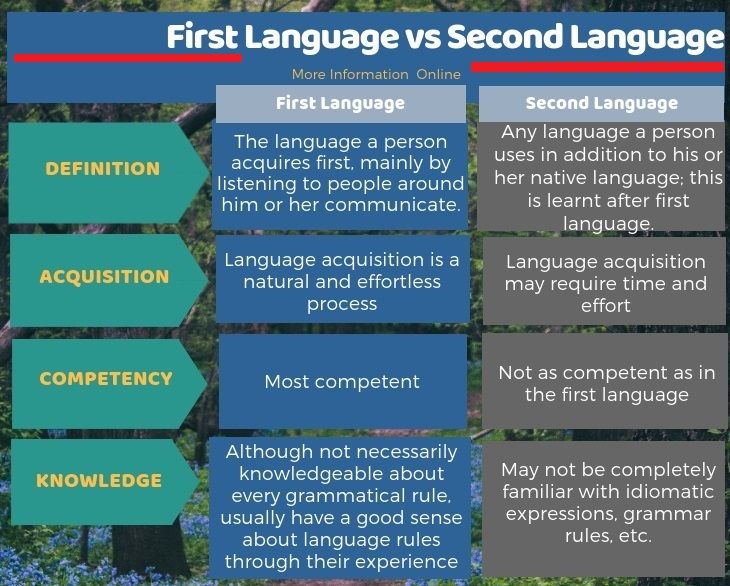

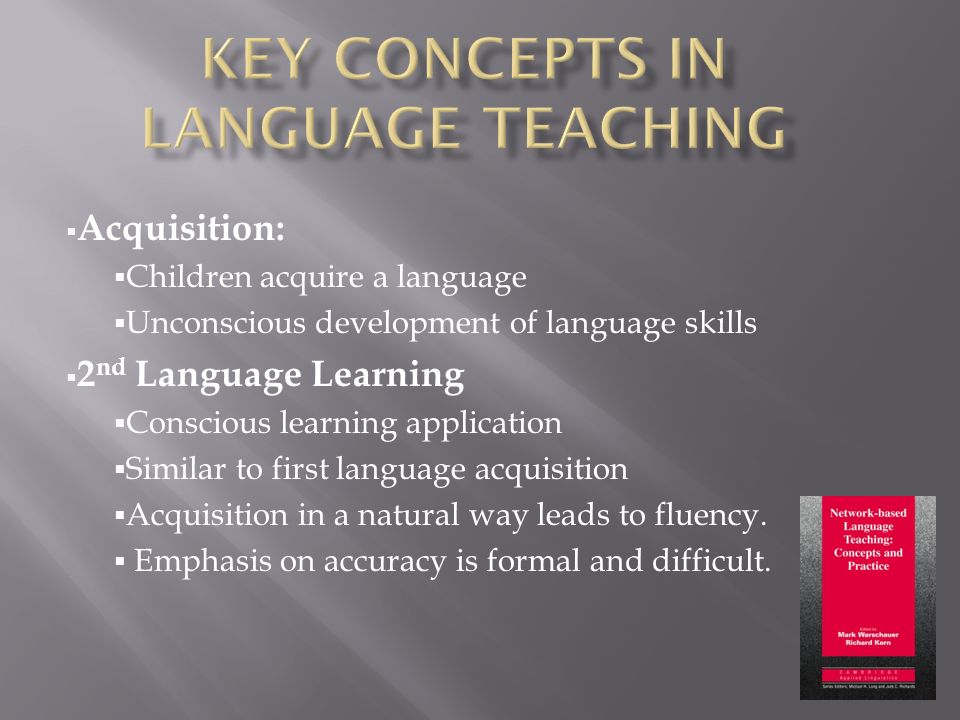

So in order for the innate language ability in a child to be triggered, data from the external world is needed. Ozsoy says the child is not born as a blank slate, but picks up cues from its environment. Yet these cues are nothing like learning a new language as an adult, where you learn the grammar and vocabulary in a structured manner. “In learning a second language the learners are exposed in a very formal way.”

Ozsoy says a child’s development is not immediate, that it goes in stages: “He does not come out with a full 10-word sentence at the age of eight months old. But he starts with the first word and then he progresses.“

She notes that even though there have been challenges to Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar, which posits that there is an innate mechanism in the human brain that helps children acquire language, it still has not been completely disproven.

Asked about Chomsky, and his predecessor, behaviourist psychologist BF Skinner whom Chomsky opposed, Slobin suggests he finds their work “irrelevant to language development in the 21st century,” pointing out current debates, for example, the differences between intelligent problem-solving and learning by statistical calculation, that create much more curiosity in academia.

Nature and nurture

Slobin says language is just like any other skill, and requires no special training: “A child in a small jungle community in New Guinea, for example, or in an isolated desert community in Africa, goes through the same processes, and uses the same abilities, as a child living in an apartment in Istanbul or a villa in Paris.”

This is what “nature” provides, he writes, the biological equipment, the learning capacity of the child, the child’s perceptual and motor coordination abilities, and cognitive processes that are “built-in” into all human beings, whether they can hear or not, whether they are mentally challenged or of above average intelligence, and regardless of where they live.

Slobin groups all that is outside of “nature” into “nurture” and says both aspects play equal and essential roles. While the study of nature, he notes, is in the realm of neuroscientists and biological psychologists, the study of nurture is of interest to psychologists, anthropologists and linguists, he delineates.

Slobin notes that to learn any particular language, you have to learn how to say the things that are required by the structure of that language.

He gives an example of Turkish, in which a child explains to his grandmother that his father has gone to work. Whether he witnessed him leaving or not will change the verb tense he uses: Ise gitti, for having seen daddy leave, and Ise gitmis, for having heard about daddy leaving for work.

Slobin says “Turkish requires the speaker to be clear about the source of information. This is systematically built into the language. You have no neutral way of saying ‘went to work’. The language forces you to say how you know.”

The language forces you to say how you know.”

Slobin then gives an example from English, in which a child says I put the ball on the table, or I put the ball in the box. Slobin makes the distinction: “The language requires him to pay attention to in versus on.” A Turkish child may say masaya koydum, kutuya koydum, putting the same directional suffix, -ya on both masa and kutu.

“In Turkish you don’t have to attend—every time you say something—to whether an object is located on a surface or in a container. You know this, of course, because of the difference between tables and boxes, just as an English speaker knows if he saw daddy go to work or only heard about it or inferred it.

“But each language trains the child to pay attention to particular aspects of experience because they are required for using words of that language. Those kinds of attention become habitual. They remain in the background. But they are always present. And they make it difficult to learn a language that makes different kinds of distinctions. ”

”

Ideas today

Slobin says there are many different beliefs and ideologies these days, some scientific, some political. There’s one he disagrees with: That a parent is responsible for teaching the child language. He believes that “the child will always learn language” regardless of the parent’s actions. Yet, of course, the child’s language acquisition process could be helped by “engaging the child in mutual conversation” with sentences and questions that go beyond orders and yes/no questions.

Slobin also says reading to the child is especially important because it provides settings that may be outside the child’s everyday experience and words and verbs for things and actions, feelings and so forth.

“The most useful kind of reading, for language learning,” Slobin says, “is to engage the child in discussion of what is being read, and to use reading materials supported by pictures.”

Slobin also champions bilingualism or learning even more languages while the child is young, despite a common belief that it may be difficult for the child. He says a child can easily acquire two or more languages, as long as they are “all used in meaningful communication.”

He says a child can easily acquire two or more languages, as long as they are “all used in meaningful communication.”

He says it may even be more beneficial to the child to learn more than one language, as, he says, there is increasing evidence that it creates “a sort of cognitive flexibility.” He gives an example of problem solving, where a child knows multiple ways of talking about a problem in different languages, and attempts different ways of resolving it.

Slobin also disagrees with the common belief that some languages are more ‘primitive’ while others are more ‘advanced.’ He says that “all languages are equally complex and equally easy to acquire in the first few years of life.” He notes that while, of course, each language comes with its own set of challenges, there is “no language that’s so easy that a three-year-old can speak it perfectly, or so difficult that a five-year-old can barely speak.”

Source: TRT World

Article | How Babies Learn Language

At six months, babies can recognize and reproduce the sounds of any language; only by 10–12 months does the mother tongue take a special place

The baby listens to and remembers the sounds of his mother's voice even before birth. Having been born, he gradually moves from screaming and cooing to babble, the appearance of intonation, the selection of his language from all the others. About a year the first words appear. This is how language learning begins.

Having been born, he gradually moves from screaming and cooing to babble, the appearance of intonation, the selection of his language from all the others. About a year the first words appear. This is how language learning begins.

The first cry of a baby at birth is his loud statement about the thirst for communication. From the very beginning of his life, still unconsciously, having no idea about the ways and methods of learning, the baby strives with all his might to master the skills of communicating with the world.

Stages of development

From the outside, the process of mastering speech looks very simple ... The child is born - he cries and screams. The first sound manifestation of the child is a cry, a non-verbal signal, followed by vocalizations - any other sounds produced by the articulatory organs. By 2 months, the baby begins to walk and laugh. At 6 months, babble appears in his "speech".

Closer to a year, the baby enthusiastically tries to pronounce the first words that only mom and dad can make out, and at 1. 5 years there is a real breakthrough, and his vocabulary expands rapidly. At 2 years old, the child tries to pronounce the first phrases, first from two words, then from several, however, still in a telegraph style, without prepositions, conjunctions and particles, and at 3 years old - plus or minus - begins to speak. Everything! It seems that the child has mastered the sounds, learned to compare them and put them into speech, imitating adults, and, therefore, “learned to speak”!

5 years there is a real breakthrough, and his vocabulary expands rapidly. At 2 years old, the child tries to pronounce the first phrases, first from two words, then from several, however, still in a telegraph style, without prepositions, conjunctions and particles, and at 3 years old - plus or minus - begins to speak. Everything! It seems that the child has mastered the sounds, learned to compare them and put them into speech, imitating adults, and, therefore, “learned to speak”!

Obviously, this impression is misleading. Language acquisition is one of the longest, most complex and mysterious cognitive processes in human life. Its most important property is spontaneity. From the outside, it seems to an adult that this is easy for a child.

View from different sciences

Researchers study speech acquisition at many levels: phonological, morphological, semantic, syntactic… But today, this issue is not only addressed by linguistics. Neuroscience, cognitive psychology, cross-linguistic research open up new facets of the problem, and in addition, they continue the long-standing debate of scientists about innate and acquired factors. They are also concerned about the relationship between the mechanisms of imitation of adults (imitation) and generalization of information received from them (generalization) in language acquisition.

They are also concerned about the relationship between the mechanisms of imitation of adults (imitation) and generalization of information received from them (generalization) in language acquisition.

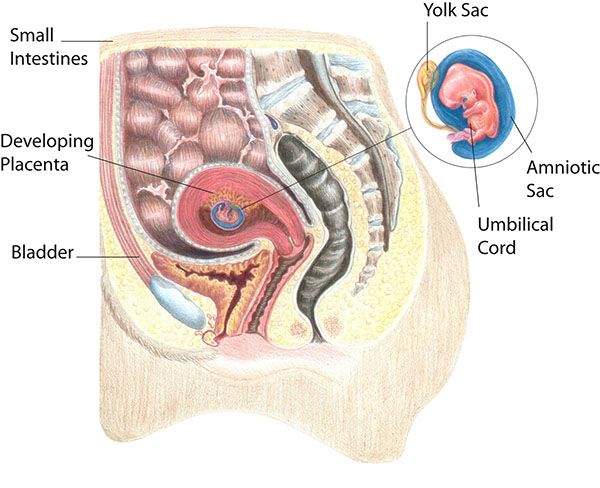

Mastering the native language begins with the perception of sounds. And this happens even before the baby is born. When a child begins to develop hearing in utero, he already hears well and knows his mother's voice. Moreover, according to research, the unborn child distinguishes what language she speaks: if the mother speaks in a foreign language, he will react to it. At the 40th week of intrauterine development, the baby prefers sequences of words (not just sounds!) that he has already heard before.

Learning through communication

After the birth of a baby, the human voice is keenly interested, and especially the voice of the mother, already familiar to him. Moreover, he prefers speech in his native language with characteristic intonations to all other sounds.

At the same time, the baby is not just a listener, he is aimed at active communication.

- The infant always tries to fixate on the face of the adult speaking to him, he even tries to imitate the movements of the lips; his fingers imperceptibly move to the beat of human speech.

- At the age of about 2 months, in the presence of an adult, the baby has the first cries of joy.

- Closer to 4 months, the child already knows his name and can initiate communication with an adult on his own. Now he understands that his verbal manifestations, crying, for example, have consequences: this way you can attract a parent. The kid screams and waits for an answer.

Gradually, the child masters the concept of turn in speech, the change of roles of the speaker and the listener: he begins to interact with adults with the help of "talk". At 5 months, the baby perfectly imitates the intonation of adults and can already control the frequency and duration of his "statements".

By the age of six months, babbling appears, the child learns to combine consonants and vowels and willingly repeats "ba-ba-ba" or "da-da-da", not necessarily typical of the native language.

At 7-8 months there is a big leap: the baby begins to understand the first words (even if he is not yet able to pronounce them himself), often associated with specific situations (for example, the moment of farewell, the “goodbye” ritual). The child really likes the special mother language that is found in all cultures. This is the speech of the mother addressed to the child, when she speaks slowly, exaggeratedly drawing out her words, loudly, with pauses and exaggerated intonations. In order for the child to understand him better and be able to follow him, the adult speaks in a simplified way, repeating the same thing over and over again, exaggerating, modulating, even singing, using not quite correct phrases, sometimes calling himself and the child by name, and not using a pronoun, using many diminutive forms, describing the actions of the child as common with him (“we wash ourselves”, “who is so handsome with us”).

According to Patricia Kuhl, an early childhood education specialist, a child is born a global citizen and then becomes an expert in one or two languages. By 10–12 months, the ability to distinguish any sounds of any language and practice their pronunciation is significantly reduced. Now the child pronounces only those syllables that are characteristic of his native language.

By 10–12 months, the ability to distinguish any sounds of any language and practice their pronunciation is significantly reduced. Now the child pronounces only those syllables that are characteristic of his native language.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/G2XBIkHW954

Initially, babies are able to recognize significant differences between sounds in different languages of the world. Gradually they lose this universal ability. That is why from a certain age (7–8 years) we can no longer learn a foreign language in such a way as to speak without an accent.

At the age of one year, the next phase of speech development begins, when one word of the child carries the meaning of the whole sentence. At this stage, the baby says so many things that, as a rule, only parents understand him, and even then not always. At this age, the child understands much more words than he can speak: somewhere around 30, after 2 months - already about 60 words.

Congenital or acquired

We all have an innate need for communication, but language as the main means of communication is directly related to the social and cultural circumstances of our lives. The development of speech in each child depends both on his abilities and on his environment. A child can learn a language only in interaction with another person and precisely in order to communicate with others. It is interesting that if a child contacts a language only through an audio channel or sees a person speaking the language only on the monitor, then he does not acquire this language at the level of his native language. For this to happen, live communication is necessary.

The impact of environmental factors, everything that surrounds the child, begins from the first days. According to one well-known study, only 12% of the words that children learn first (“mom”, “dad”, “give” ...) will be approximately the same in meaning for all babies, regardless of language. Then the differences begin. French babies have "hedonic" first verbal experiences: they talk about food three times as much as children from other cultures. The first words of little Americans are dedicated to people, relatives and friends. Swedish kids are actively interested in household items, while Japanese kids care about politeness and ... ecology!

Then the differences begin. French babies have "hedonic" first verbal experiences: they talk about food three times as much as children from other cultures. The first words of little Americans are dedicated to people, relatives and friends. Swedish kids are actively interested in household items, while Japanese kids care about politeness and ... ecology!

Need to communicate more

Some children start talking earlier than others and use more words. The difference can be seen as early as 3 months of age. It has been noticed that the more often a child interacts with an adult, the more sounds he tries to reproduce. The vocabulary of a child, the richness of his speech, the pleasure of communication largely depend on how much and how involved adults communicate with him. Therefore, you should communicate with the baby as often as possible and respond to all his attempts to interact. In addition, even if the baby is “not a talker” by nature, shy and timid, it is worth encouraging any manifestations of his desire to establish communication and more often call for a “dialogue”.

Photo: Collection/iStock, Unsplash, Pexels

How do children learn language?

Image by Alexandra_Koch from Pixabay

Linguist Ekaterina Protasova explains how vocabulary is developed, whether bilinguals have advantages, and how a child decides which language to speak.

You will find even more materials on the topic "Psychology of Child Development" in our library. A selection of articles, video lectures, cartoons, interviews, tests, lists of useful literature has been prepared for you by our foundation in cooperation with the PostNauka website.

How children learn language

Every year, millions of people learn their native language, but how this happens is still a mystery. We launched the project Developmental Psychology: How Children Learn to Understand and Manage Emotions, prepared jointly with the Sberbank Charitable Foundation Contribution to the Future. Linguist Ekaterina Protasova told how children learn to speak.

Linguist Ekaterina Protasova told how children learn to speak.

Man learned to speak, according to scientists, from 50 to 150 thousand years ago. There are currently 7.5 billion people on earth. There have been more than 100 billion people who have spoken throughout history. At the same time, we still do not exactly understand how phonetics, semantics, grammar, and pragmatics are mastered. It is easier to understand how the vocabulary is acquired (it is still not clear why we remember some word from one presentation, and we do not learn the other in any way).

Language learning puzzle

The mystery of how exactly a person masters his native language remains unsolved. Every year, millions of people learn languages, each their own, and these processes have been described in the entire history of science only for dozens of children around the world. For most languages, no one has ever studied this!

There is an idea in biology that ontogeny repeats phylogeny, that is, it is possible that the way humanity has learned to speak is reflected in the history of language acquisition by each person. In works on linguistic typology today, data from children's speech are involved in order to understand how language and thinking correlate, what forms of language are in principle possible. It turns out that in the speech of a child who masters any native language, there are almost all the phenomena that are characteristic of different languages of the world; over time they disappear, being replaced by regular forms.

In works on linguistic typology today, data from children's speech are involved in order to understand how language and thinking correlate, what forms of language are in principle possible. It turns out that in the speech of a child who masters any native language, there are almost all the phenomena that are characteristic of different languages of the world; over time they disappear, being replaced by regular forms.

Where language comes from

Let's see at what time people began to worry about where their language comes from. We will have to go back to the 7th century BC - this is the first recorded evidence. Herodotus writes about this in his "History": the Egyptian king Psammetich decided to find out what two children who were settled in a cave and served in silence by some nannies would say. When they were about two years old, they uttered the word "bekos". I had to find out in which language such a word exists, and it turned out that this word meant "bread" in Phrygian. The Egyptian king had to admit that the Phrygians were older than the Egyptians - then it was important which people appeared first on earth.

The Egyptian king had to admit that the Phrygians were older than the Egyptians - then it was important which people appeared first on earth.

Why do people even turn to this topic? In the history of science, it is very important what ideas occupy us when we start doing some experiments, when we start asking questions “why?” and where?". Starting with Plato and the Sanskrit grammarians, it was very important to know: the language is already in a person when he is born, so it remains to “manifest”, “pull out”, or is it given to a person in some way,

is it breathed into him, perhaps by divine power, or does everything happen thanks to the upbringing of those around him?

Today we ask questions differently. How to count language? To build a self-learning speech model in the manner of a person? Can we predict from the very beginning what kind of speech a person with a certain genetic code will have? How to correct speech development disorders? (There are a lot of them: every fifth person has something noticeably wrong, and everyone has certain deviations. ) How to learn a lot of languages?

) How to learn a lot of languages?

Who studied the emergence of language today

The child's speech is studied by philosophers, psychologists, teachers, philologists, psycho- and neurophysiologists, psycho- and neurolinguists. Some, like Burres Frederick Skinner, believe that the child acquires language through trial and error, and adults reinforce the correct forms. Others, like Noam Chomsky, believe that there is a capacity for language acquisition within the newborn.

Interestingly, the child never reproduces exactly what adults say, but always brings something of his own. Psychologists Jean Piaget, Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky, Jerome Bruner made a great contribution to the understanding of these processes. Theories of language acquisition take into account cognitive competence, knowledge of the surrounding world, the complexity of the expressed content and ways of its transmission in the language, frequency, visibility and availability of means of expression. Mowgli children and twins are of particular interest.

Mowgli children and twins are of particular interest.

Jean William Fritz Piaget - Swiss psychologist and philosopher, known for his work on the study of the psychology of children, the creator of the theory of cognitive development.

Observation diaries

Different people kept records of how the child acquires the language. The first diary of observations known to us dates back to the end of the 18th century - it was the German scientist Dietrich Tiedemann, who recorded the speech of his child. The diary of children's speech was important to the biologist Charles Darwin and the neuropsychologist Alexander Romanovich Luria. Quite a few diaries appeared at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. At the same time, there were also the first diaries of the development of the speech of a Russian-speaking child.

Recording speech after a child is quite difficult, because you either constantly observe and participate in how speech is mastered, or you get distracted from what the child is doing and begin to write frantically. When tape recorders were invented, the question arose of where to limit the recording of speech (today, when analyzing Big Data, this will no longer be a problem).

When tape recorders were invented, the question arose of where to limit the recording of speech (today, when analyzing Big Data, this will no longer be a problem).

At first, it was so expensive to record a child's speech that the restrictions were purely financial. When video recorders and other means of recording sound along with the visual range appeared, it became interesting to trace the gradual development of speech, the relationship of gestures, eye movements and location in space with articulation, the relationship between adult and child speech, words and deeds. A painstaking analysis of what is happening and heard takes a lot of time. Do not forget that all this is part of communication, the formation of interpersonal communication.

Large linguistic corpora are collected from speech recordings, thanks to which it is possible to find out which words and constructions appear when and how they develop. In addition, cross-sectional experiments can be carried out: to give many children of the same age the same task for understanding, reproduction, addition, story, retelling, description,

paraphrasing, seeking answers to questions, turning statements into questions or denials and vice versa, and then repeating the same with children of the next age.

All these operations on speech have different psycholinguistic complexity. With older children, similar processes are explored during reading and writing. Experimental material should be carefully selected both from the point of view of linguistic phenomena and from the point of view of clarity. It is also necessary to take into account who and how communicates with children at the time of the experiment, in what environment the experiment is conducted. The behavior of a child at the time of processing speech information can be monitored by analyzing eye movements, as well as taking indicators of brain and physical activity.

From cooing and babble to words

In Russian, they speak of cooing, that is, the pronunciation of certain syllables, and babbling, when certain prototypes of future phonemic constructions can already be distinguished in them. Up to six to eight months, the child is able to produce amorphous sounds, from which the sound system of his native language is then formed. The baby responds to intonation.

The baby responds to intonation.

About a year should appear the first words of the child, some children have them as early as five months, some only one and a half years. The first two-word sentences appear by the age of one and a half. It is believed that when a child has mastered about 50 words, he can combine them into constructions. For example, a construction with the word "give": after the word "give" a large number of different nouns will be substituted. Service words, as a rule, appear a little later.

How vocabulary is developed

As in phonetics, at first we cannot say exactly what sound a child utters, so when mastering words, we also talk about amorphous words that practically mean a lot, in a form that is difficult to pronounce, difficult to reproduce by adults. And the child uses them to designate many situations. For example, the word "boots": some children say "tititi", some say "botiba" from such a babbling word "boti" - shortening the word "boots" and adding the next syllable. This childish word "boots" can mean "let's go for a walk", "dad's gone to work" or "I want to play with something brown", the same color as these boots.

This childish word "boots" can mean "let's go for a walk", "dad's gone to work" or "I want to play with something brown", the same color as these boots.

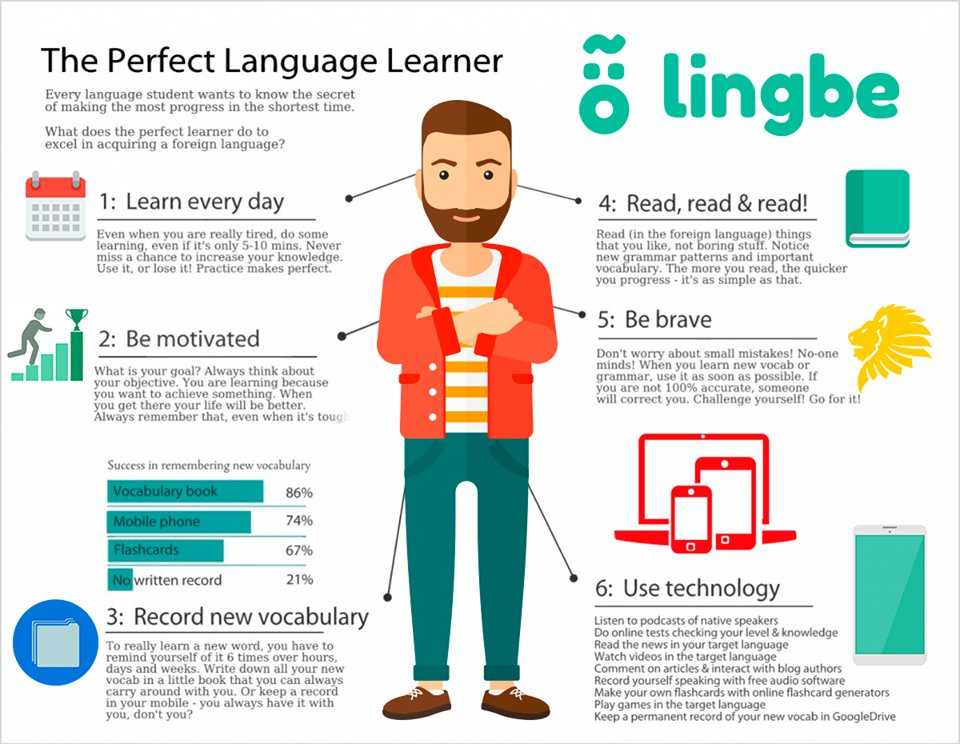

In a year and a half, a fairly rapid growth of the dictionary begins. From the age of two, a child learns about 10-15 words a day. First, he learns to understand them, and then to use them - first in familiar situations, and then in unfamiliar ones. By the time he enters school, he already knows several thousand words. Speech does not end at school: the written basis, the normalization of what was learned orally, turns out to be a very big impetus in the development of speech. Gradually assimilated, for example, spelling, punctuation, style, scientific terminology.

How bilinguals learn a language

If the child's parents speak different languages to him, the child can learn two languages at the same time. Each of these languages is acquired in the same sequence as in a monolingual child, perhaps somewhat more slowly. Sometimes it happens that, compared with peers, the vocabulary of a child is one of

Sometimes it happens that, compared with peers, the vocabulary of a child is one of

languages may be somewhat less, although if you collect the words of both languages, then the result will be much more than that of a monolingual child. There should be a sufficient input: to build a language, there should be enough speech that adults address the child in each of the languages.

A person who has been accustomed to speaking two languages from childhood develops a special cognitive ability: he can more easily navigate in a changing situation, make decisions faster, he develops the ability to abstract thinking earlier. Almost all famous writers of the 19th century were at least bilingual, and often trilingual from childhood, including Pushkin.

The number of bilinguals in the world is huge. There are countries where bilingualism is the norm. People live, for example, in a situation of diglossia, when they speak one language in society, and another in the family. A multilingual society is multilingual, and a person who has learned languages as school subjects is plurilingual. A polyglot is someone who has mastered at least five languages after the age of 15–16, in the so-called post-puberty period.

A multilingual society is multilingual, and a person who has learned languages as school subjects is plurilingual. A polyglot is someone who has mastered at least five languages after the age of 15–16, in the so-called post-puberty period.

Image by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay

How a child decides which language to speak

The peculiarity of bilingualism is that most of the sentences that the child uses are not a mixture of two languages. In principle, they get used to the fact that there are different options for describing the environment, and use words within these systems. However, there are times when, for example, a child attaches the Russian suffix "-ichka" to the English word dog - it turns out "dogichka". He uses the words of two languages one after another, speaks about some phenomena in one language, about others in another, or divides languages according to spheres or places of use.

The child may assume that all women talk like mom and all men talk like dad. Or all the items mom uses should be named in her language, and all items dad uses should be named in his language. Or all mom's friends speak her language, all dad's friends speak his language. These types of decisions are usually short-lived and do not define a person's life forever.

Bilingual children are quite capable of learning to write in two languages at the same time. They can start reading in one language and then transfer the skills they have learned to a second language. Individual variability in children is very high. Having reached a certain level, say, in storytelling, reading, some kind of game, the child can further use this skill very well and is able, after some training, to transfer it to a similar activity in a second language.

The ability to learn two languages at the same time as native is retained until about the age of 7–8 years, and then, after the written basis of speech is mastered, the ability to learn the language in natural communication fades, which is typical for the first language acquisition. This is not to say that all children develop in the same way: someone will perfectly master a second language at any age. However, bilinguals, on average, have a much greater ability to learn any third language than a person who did not learn a second language during their preschool childhood.

This is not to say that all children develop in the same way: someone will perfectly master a second language at any age. However, bilinguals, on average, have a much greater ability to learn any third language than a person who did not learn a second language during their preschool childhood.

You can read:

- A. N. Gvozdev. Questions of studying children's speech.

- K. I. Chukovsky. From two to five.

- M. M. Koltsova. The child is learning to speak.

- E. I. Negnevitskaya, A. M. Shakhnarovich. Children and languages.

- N. I. Lepskaya. Child language.

- S. Pinker. Language as an instinct.

- S. N. Zeitlin. Language and child: Linguistics of children's speech.

- E. Yu. Protasova, N. M. Rodina. Multilingualism in childhood.

- M. D. Voeikova. Name formation.

- V. V. Kazakovskaya. Question-answer unities in the "adult-child" dialogue.

- M. B. Eliseeva. The formation of the individual language system of the child.