18 month old not walking

6 Signs Baby Will Walk Soon and How to Encourage Walking

From recording that first smile and rollover to proudly sharing your baby’s skill at sitting up and crawling, you’re on the edge of your rocking chair waiting for your little one’s next move.

And one of the most game-changing milestones might be approaching soon — taking those first adorable, wobbly steps.

Walking is a greatly anticipated infant achievement. It’s a sure sign that your little one is entering the toddler zone (and some serious babyproofing is in your near future).

But you might also be wondering if walking early or “late” is related to intelligence and even physical performance in the future.

While a 2015 cross-national study correlated learning to walk with advancing language abilities in infancy, rest assured: Research suggests that there’s no proven association between walking early and becoming the next Isaac Newton or Serena Williams.

In fact, according to this Swiss study in 2013, children who started walking early didn’t perform better on intelligence and motor skills tests between the ages of 7 and 18 compared to babies who did not walk early. What this study did conclude, however, is this:

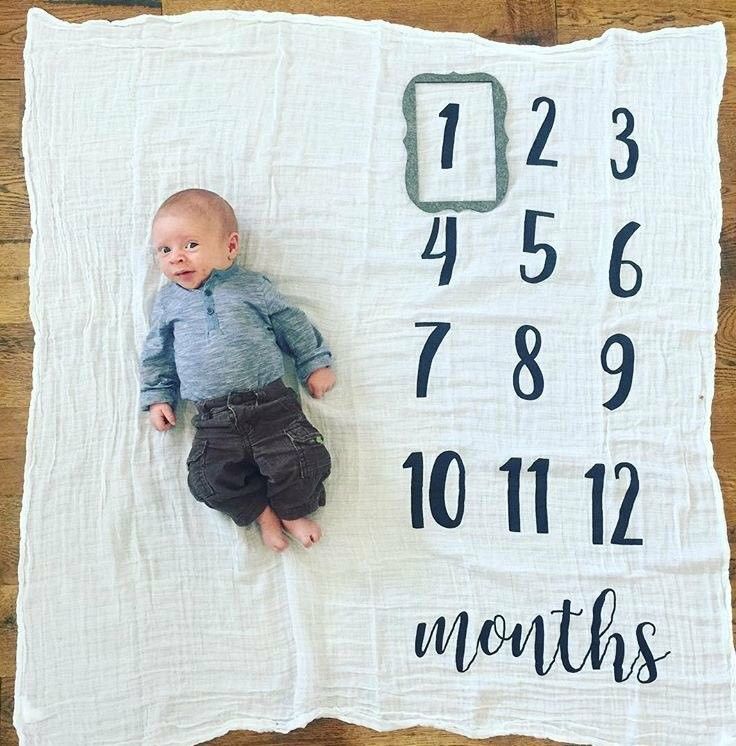

There’s a tremendous variance in when babies decide to start strutting — usually between 8 1/2 and 20 months.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) acknowledges that these walking-related physical milestones are typically met by age 1:

- pulling up to stand

- walking while holding on to furniture

- may be taking a few independent steps

- standing holding on and may stand alone

We know you want to capture those first steps in your heart (and on video) forever, so let’s take a more in-depth look at these and other signs that toddling is imminent.

Pulling up on furniture to stand is one of the first signs of walking readiness.

This boosts babies’ leg muscles and coordination — just think of how many squats they’re doing! Over time, the mini workouts condition your baby to stand independently, and then, move ahead with a few wobbly steps.

You can encourage this by modeling their movements while saying “up!” as they pull up, and “down!” as they squat down again.

If, out of the corner of your eye, you catch your sweet Houdini suddenly standing on top of the couch and smiling while ready to nosedive, it might be a sign that their inner confidence is shining.

While this puts you on accident alert — and on catcher’s duty — it’s a great developmental signal that your baby is confident about trying new things (however dangerous they may be). To walk independently, babies must have self-efficacy in their ability to do it.

So if you’re catching yourself helicopter-momming-it, try to find your zen and let your little explorer push their physical abilities — in a safe environment.

“Cruising” describes a baby walking while holding onto objects. They might use the coffee table to move around or lean from one object to another to work the room.

This shows that your tiny sport is learning how to shift weight and balance while taking steps. It also prepares for the ability to propel forward, which is required for walking.

It also prepares for the ability to propel forward, which is required for walking.

To promote cruising, create a path of safe objects for your baby to grab onto and move about.

But take caution with furniture, plants, and other items that aren’t safely secured to walls or the ground. They could topple over, leading to an accidental fall or injury.

Who would have thought that the fussiness and extra-long nap could be a tip-off that your baby will soon blaze by you on their tiptoes?

Well, walking is such a big developmental milestone that it’s often accompanied by other developmental leaps. Your baby’s brain and body could be working double time, leaving a slightly less tolerant tot.

These moments of parenthood are tough, so take a deep breath and find solace knowing that (usually) things return to normal after a developmental milestone is achieved.

Offering safe, age-appropriate push-toys (not infant walkers — more on this below) can inspire your child to walk while picking up some speed.

Infant play grocery carts or musical walking toys with wheels and handles can bring joy and assistance to beginning walkers. You can also hold your baby’s hand or give them a blanket to hold while you hold the other end and walk.

The look on a baby’s face when they first stand alone is often one of accomplishment (and perhaps an ounce of fear, too).

At this moment, babies have the balance and stability to stand on their own. They often test the waters for a few seconds, and then gradually stand for longer periods of time, boosting confidence to take it a step further.

Make it a fun learning activity by slowly counting for as long as your child stands.

If your baby shows signs of readiness, consider these activities to boost their self-efficacy and strength.

To promote walking:

- Deliver praise. Watch for baby’s cues that they’re ready to advance — and praise every achievement. Help when needed, and sit back with a smile when you see that glimmer of self-determination in their eyes.

- Comfort a fall. Falls are inevitable in the infancy of walking, so be there to help your little one up again and console a few tears. Babyproofing is important at this stage to create the safest environment possible for your baby to explore.

- Create challenges. If your baby has mastered walking on flat surfaces, challenge them by walking up and down a ramp or on a safe, uneven surface. This helps build more balance, coordination, and muscle power.

- Extend a hand. Encourage your baby to walk to you as you extend your hands toward them. You can also ask them to follow you as you walk into another room.

You might want your baby to defy all statistics, but it’s vital to encourage walking in a positive, safe, and developmentally appropriate way. Here are some things to avoid.

Avoid the following:

- Don’t use infant walkers. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends against using infant walkers, citing that they’re a preventable and dangerous cause of infant injury in the United States.

These injuries usually occur to the head and neck after a fall down stairs. Stationary infant activity centers (like a Jumperoo or Excersaucer) are safer bets.

These injuries usually occur to the head and neck after a fall down stairs. Stationary infant activity centers (like a Jumperoo or Excersaucer) are safer bets. - Avoid pushing your own milestone goals. Be mindful of pushing children to achieve goals before they’re ready to do so on their own. This can result in negative experiences or injuries that could delay walking even further.

If your baby isn’t meeting these physical milestones by their first birthday, should you be concerned? Not quite.

The CDC recommends talking to your child’s pediatrician if they’re not walking at all by 18 months and not walking steadily by age 2 — so you have plenty of time even if your little one hasn’t started showing signs by age 1.

You may also worry that even a slight delay in walking could indicate additional developmental and neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism.

While the results of a small 2012 study concluded that early motor delays may be a risk factor for future communication delays in children at risk of autism, for children with a low risk of autism, parents should not jump to this assumption.

There are many reasons for late walking in babies. Some are physical (and not common), such as:

- developmental hip dysplasia

- soft or weak bones (medically termed rickets)

- conditions that affect the muscle (for example, muscular dystrophy or cerebral palsy)

Other times, the delay could be mere personality.

While walking may seem like it’s as simple as putting one foot in front of the other, for a baby, it’s a monumental achievement that takes physical strength, confidence, and a safe place to practice.

And although your baby is smart enough to get to this milestone on their own, a supportive coach certainly doesn’t hurt, either (that’s you!).

Some of these signs might tell you that your baby is ready to walk, but each child’s “go time” is that of their own.

Lastly, if you’re ever concerned about your child’s physical development, speak to their pediatrician for professional guidance and support.

Your child doesn't walk yet

What you may notice

If your child continues to crawl, creep, or scoot on his bottom while other children his age are walking, you may be concerned about his motor development. Not walking at 18 months could fall into the "unusual but possibly normal" category, says Andrew Adesman, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Schneider Children's Hospital in New York, but it could also signal that something is wrong.

Not walking at 18 months could fall into the "unusual but possibly normal" category, says Andrew Adesman, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Schneider Children's Hospital in New York, but it could also signal that something is wrong.

What causes it

If your toddler is developing normally in other ways, it might be that she just hasn't had enough encouragement or opportunity.

"I always look at familial or environmental factors," says physical therapist Gay Girolami. "You might find you have a really busy family and the child spends a lot of time in a baby exerciser so she's learned to bounce around on her tiptoes. When she gets to the standing stage, she has trouble because her trunk and pelvic muscles have not been worked enough." (Some experts recommend against using baby exercisers for this reason.)

The same goes for baby walkers, which sound like they'll help a baby learn to walk but do the opposite – and they're dangerous. The American Academy of Pediatrics advises parents not to use baby walkers because they're unsafe and don't help babies develop the muscles needed to master the skill of walking.

In addition, there are other environmental factors to consider. "Most kids desperately want to walk – but a child who's carried everywhere in a backpack or car seat and handed everything she desires may not see much of a reason to exert herself," says Girolami.

You can find other ways to encourage your child to develop her walking skills.

Both low muscle tone (hypotonia) and high muscle tone (hypertonia) can make walking difficult. If muscle tone is too low, a child will have a hard time gaining balance and control over gravity because her limbs are floppy. If her muscle tone is too high, or if certain muscle groups are overactive, she may have stiff limbs and a hard time sustaining balance. In rare cases, doctors diagnose hip problems when a child doesn't walk on time.

Late walking can also be associated with developmental issues such as an intellectual disability.

If you're concerned that your child is late to start walking, the first step is a medical examination, including a neurological exam and an assessment of your child's reflexes, posture, and muscle tone. The doctor will also take into account other developmental issues including language, fine motor, and social skills.

The doctor will also take into account other developmental issues including language, fine motor, and social skills.

Advertisement | page continues below

"Late walking doesn't usually come out of the blue," Adesman says. "A child who walked late probably also sat late and crawled late – it's probably not the first missed milestone you'd notice." For this reason, your doctor will probably look at your child's walking in the context of other skills and try to figure out where he is on the continuum of motor development.

If your child's doctor notices that your child has stiff or floppy limbs, she may refer you to a pediatric neurologist (a doctor who specializes in children's brain development). If there are delays in other areas, such as your child's language or fine motor skills, she may refer you to a developmental pediatrician. If a cause is identified, appropriate care could range from physical therapy to improve strength and flexibility or surgery to correct a physical problem.

If your child's doctor can't identify a reason your toddler's not walking, she may simply recommend some games and play periods that involve encouragement and practice and have you come back for a follow-up exam at a later date. She might also recommend physical therapy, which would allow a trained professional to closely monitor your toddler's progress.

Next warning sign: Your child walks on her toes

Back to 10 red flags for toddler motor development

Was this article helpful?

Yes

No

Why do parents panic so much if the child does not start walking for a long time

“When did yours start walking?” is a fairly typical question that can be heard on the playground. But for parents whose children are still crawling a year old, it can be very painful. Brown University economics professor and author of two parenting books, Emily Oster, shares the stress she went through until her daughter started walking and why it was all for nothing.

It's simply ridiculous and ridiculous how many expectations and conventions are formed around the birth of a child and his upbringing. But in the process of writing two books about this, I realized that there are things that are almost impossible to predict. People don't talk about them because they're sad, uncomfortable, or just plain weird. It seems to me that we should discuss them more often and, moreover, rely on facts to better understand them (I am an economist, I love facts). nine0003

Recognizing their importance will help reduce pressure on parents. After all, the facts either reflect the experience already gained by someone, even when the situation seems unique, or give us more options than it seems, how to act.

My friend Jane had a son three months after my daughter. Now they are both in the second grade, and you will hardly notice their age difference. But at the very beginning it was hard to believe in this. When Benjamin was born, Penelope already seemed like a giant. When he was a plump, soft six-week-old baby, she was already four and a half months old and was gradually turning into a real baby. nine0003

When he was a plump, soft six-week-old baby, she was already four and a half months old and was gradually turning into a real baby. nine0003

But then it was time for the first steps. Like any average child, Benjamin got up at the age of one and began to stagger around. But not Penelope. By the time he left, she was 15 months old and seemed to have no intention of doing anything like that. In some cases, it's easy to ignore your child's differences from most other children. But not in the case of walking, because it is so important, so noticeable. In addition, we constantly saw Benjamin, so it was difficult to avoid comparisons. nine0003

On another visit to our down-to-earth and pragmatic pediatrician, Dr. Li, she told me not to worry that Penelope wasn't walking yet.

“If she doesn't go by 18 months, then we'll check. But don't worry! She can handle it.”

I couldn't share Dr. Li's relaxed confidence, I didn't have the breadth of her experience. So I tried to explain to Penelope how to walk; she paid no attention to it. I tried to somehow stimulate her, but it was also useless. You remember, she was just a child. nine0003

I tried to somehow stimulate her, but it was also useless. You remember, she was just a child. nine0003

And one day, two weeks after the doctor's visit, Penelope went. As if it was not difficult for her. Perhaps due to the fact that she was older than the others, she hardly fell, but simply went from crawling to full walking in just a day or two. Soon I forgot my fear and moved on to other neuroses. (When you're a parent, there's excitement around every corner.)

I don't think my experience is unique. Today, the main stages of physical development - sitting, crawling, walking, running - are given too much importance. Becoming a parent, you find yourself in a new and shocking world. These milestones seem like almost the only map of unfamiliar territory. Therefore, the inability to pass them on time, at the age that we read about, becomes a cause for unrest. nine0003

Part of the problem is that all the talk is centered on middle age, such as "most children start walking at one year old. " This is true, but in doing so we miss the (perhaps surprising) fact that everything that is typical has very, very vague boundaries. To learn how to understand them, we must turn to data collected from healthy, normally developing children.

" This is true, but in doing so we miss the (perhaps surprising) fact that everything that is typical has very, very vague boundaries. To learn how to understand them, we must turn to data collected from healthy, normally developing children.

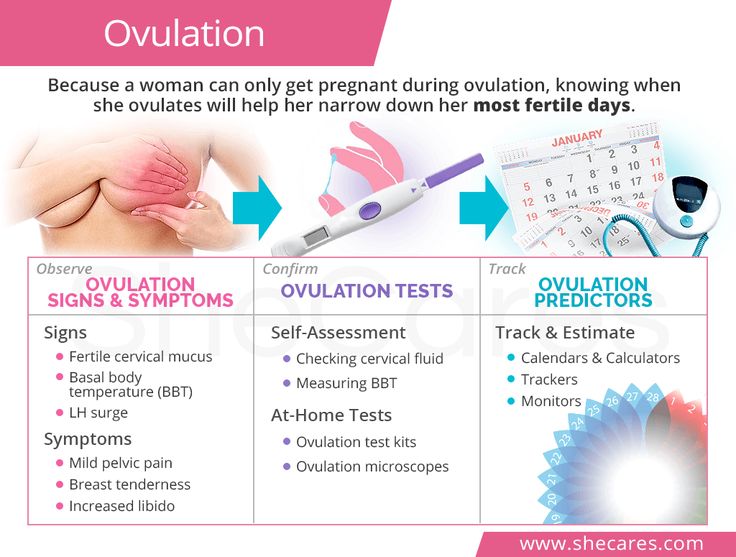

In particular, we can use the WHO data to find out not only the average age when children start walking (it really fluctuates around a year), but to take into account the entire possible spectrum. The age range is shown in the graph below. On it, we see that the earliest age is about 8 months, and the latest is about 18.

Consider how amazingly wide this range is! It simultaneously includes both eight-month-old and eighteen-month-old children, who radically differ in the level of development. In this case, both ages are considered normal for the first steps. This leads to the thought of how different children can already be at this stage and how we should see the stages of development - as a range.

Child development research provides other amazing facts about a wide range of milestones. Most of them are very comforting. For example, many children either never crawl at all, or do it in a very unusual way. I think a lot of pediatricians have answered parents' questions about why their child moves around the house like a worm. nine0003

Most of them are very comforting. For example, many children either never crawl at all, or do it in a very unusual way. I think a lot of pediatricians have answered parents' questions about why their child moves around the house like a worm. nine0003

This is generally encouraging, but many mothers and fathers still have the question: is it possible to predict something? If your child doesn't walk until 17 months, isn't he doomed to be the last in the sport in advance? In fact, there is very little evidence of the long-term impact of a child going later than others.

Almost all children—even the vast majority of those who are outside the normal range—eventually begin to walk and run. If you ask if the fact that the child took his first steps early is connected with the fact that he will walk, then the answer is: "No, everyone walks." nine0003

When it comes to professional athletes, there is too little data. I don't know for sure, maybe researchers are not particularly interested in predicting sports results. Maybe the point is that even if there was some kind of relationship, the conclusion would be so implausible that we would never see it among the data. To get to the Olympics, in our opinion, is an unrealistic goal for most people.

Maybe the point is that even if there was some kind of relationship, the conclusion would be so implausible that we would never see it among the data. To get to the Olympics, in our opinion, is an unrealistic goal for most people.

So don't be surprised if your child started walking late or crawling late - or, on the contrary, walked early, or does not crawl at all. As with most parenting matters, the secret is not to panic when things go against your expectations. nine0003

Signs of a possible developmental delay in children under 5 years of age

What are "developmental norms" and how should they be perceived?

The child should be regularly seen by a pediatrician: during routine examinations, he assesses his physical and psychomotor development, examines for signs of illness and gives recommendations on nutrition and care. Ideally, parents do not have to think about anything - if something is wrong, the doctor will tell them about it. But often parents still worry that their child cannot do something that his peers can do. Studying tables and graphs of normal development often confuses them even more, because the data in them differ, and sometimes do not correspond to the truth at all. What is worth only such a criterion for normal development, which is indicated in the table, usually used in district clinics, as 10 words in 1 year. It is not often in the practice of a pediatrician that there are children who speak 10 words a year, even if they are monosyllabic (by “words” here one should understand any, but always the same, designation of a certain object: for example, a car is “bi”, a dog is “ka” or "av", etc.). nine0003

But often parents still worry that their child cannot do something that his peers can do. Studying tables and graphs of normal development often confuses them even more, because the data in them differ, and sometimes do not correspond to the truth at all. What is worth only such a criterion for normal development, which is indicated in the table, usually used in district clinics, as 10 words in 1 year. It is not often in the practice of a pediatrician that there are children who speak 10 words a year, even if they are monosyllabic (by “words” here one should understand any, but always the same, designation of a certain object: for example, a car is “bi”, a dog is “ka” or "av", etc.). nine0003

In addition, the “norms” indicated in the tables and graphs are at best a range of average values: for example, it can be stated that, on average, children begin to walk between the ages of 11 months and 1 year and 3 months. Yes, the majority behaves this way, but this “majority” is only 65%. And there are 35% of healthy children who will go sooner or later. In the worst case, the tables show only average values in general: for example, you need to sit at 6 months, walk at 1 year, etc. nine0003

And there are 35% of healthy children who will go sooner or later. In the worst case, the tables show only average values in general: for example, you need to sit at 6 months, walk at 1 year, etc. nine0003

It should also be noted that there are tables that indicate signs that do not need to be evaluated at all. For example, when a child begins to roll over from his stomach to his back, since even newborns can accidentally do this simply because of the asymmetrical tone in the arms. Or when a child starts to crawl, because in the first year of life this is an optional skill, etc.

How does a pediatrician determine which deviation from the indicated "norms" is considered a pathology? - The only correct approach is a comprehensive assessment of the development and health of the child. For example, if at the age of 1 year and 3 months he does not walk independently, but he has already developed other skills required by age and there are no signs of diseases (for example, hip dysplasia, etc. ), then the pediatrician recognizes him as healthy. Parents cannot do this on their own. nine0003

), then the pediatrician recognizes him as healthy. Parents cannot do this on their own. nine0003

There are several good scales for assessing the development of children. They are similar, but one is for a quick assessment and the other is more detailed for assessing a child who is suspected of having a delay. We will not cite them here precisely for the reason that a person trained in this should evaluate the development of a child.

Signs of developmental delay

Listed below are signs that developmental delay is likely to be present (original taken from here). Almost 100% of healthy children already have the skills indicated for each stage. However, there may not be a delay. nine0003

Be sure to see a doctor if your child is not doing any of the above.

At 2 months:

- does not respond to loud noises

- does not follow moving objects with his eyes

- does not smile at people

- does not bring his hands to his mouth

- cannot keep his head up when lying on his stomach 9006 9002

At 4 months:

- does not follow moving objects

- does not smile at people

- does not hold his head up

- does not coo or make sounds

- does not bring things to his mouth

- does not put his feet on the surface when he is placed

- cannot turn one or both eyes in all directions

At 6 months :

- does not try to grab things that are in range

- does not show affection for those who care for him

- does not react to sounds around him

- has difficulty bringing things to his mouth

- does not pronounce the vowel sounds "a", "o", "e"

- does not roll over in both directions

- does not laugh or squeal

- seems very tight, with muscles tense

- seems very flexible, like a rag doll

At 9 months:

- does not support her weight with her legs

- does not sit with help

- does not babble ("mother", "woman", "dada") gotta do something back and forth

- does not respond to his name

- does not seem to recognize loved ones

- does not look at what you point to

- does not shift the toy from one hand to the other

At 1 year:

- does not crawl 9061 does not stand with support

- does not look for things that he saw that you have hidden

- does not speak simple words (such as "mom", "dad")

- does not learn gestures (waving his hand, shaking his head, etc.

) )

) ) - does not point to things

- loses skills acquired earlier

At 1 year 6 months:

- does not point out things that he wants to show others

- does not walk

- does not know what familiar things are for

- does not repeat after others

- does not learn to speak more words

- does not speak at least 6 words

- does not notice or react when loved ones leave and come back

- loses skills that he acquired earlier

At 2 years old:

- does not say two-word phrases (e.g. “drink milk”)

- does not know what to do with frequently used items (comb, telephone, fork, spoon, etc.)

- does not repeats actions and words after others

- does not follow simple instructions

- does not walk confidently

- loses the skills he has previously acquired

At 3 years:

- often falls or has difficulty climbing stairs

- speaks nonsense or is very incomprehensible nine0062

- does not speak in sentences

- cannot play simple games (mazaiku, simple puzzles, etc.